Residential Mortgage Securitization

in Canada: A Review

Adi Mordel and Nigel Stephens

Residential mortgage securitization (together with

mortgage insurance) plays an important role in the

Canadian system of housing nance, especially given

the rising share of government-supported (i.e., public)

securitization over the past 15 years.

The main social benet for Canadians of public

securitization is the support it provides for both

diversity of choice and access to mortgage nancing

through a stable, cost-effective supply of funding to

mortgage lenders. Public securitization also supports

competition in the mortgage market by providing

funding to small lenders,

1

which have fewer alterna-

tive funding sources. Financial institutions also benet

from public securitization by using these highly rated

assets to meet regulatory requirements.

The recent increase in public securitization has also

led to public discussions about the government’s

exposure to the housing market, the balance between

investment in residential real estate and other forms

of investment, and the potential effects on household

borrowing and the housing market. One approach to

reducing the government’s involvement in the housing

market would be to consider adopting measures

to reinvigorate private mortgage securitization in

Canada.

Introduction

Mortgage securitization, the process of converting

illiquid mortgage loans into tradable securities, plays

an important role in the Canadian nancial system.

Over the past 15 years, the share of mortgage credit in

Canada that has been securitized has grown from about

1 In this report, the term “small lenders” refers to all nancial institutions that

access public securitization programs in Canada, excluding the Big Six

banks.

10 per cent to 33 per cent. Of the amount securitized

during that period, the share executed through public

securitization increased from 50 per cent to almost

100 per cent.

In this report, we analyze the evolution of both public

and private mortgage securitization in Canada to better

understand the underlying public policy and economic

determinants.

In particular, we consider the uses of mortgage securi-

tization by nancial institutions (FIs) to meet their funding

needs and regulatory liquidity requirements. As well,

we estimate that signicant benets accrue to the

nancial system as a whole from public securitization.

Aggregate mortgage funding costs are reduced by

about $870 million annually. In addition, Canadian FIs

save at least $120 million per year for every $100 billion

of National Housing Act Mortgage-Backed Securities

(NHA MBS) held for regulatory liquidity adherence.

2

We then review potential implications of the extent of

public securitization, noting that the Canadian govern-

ment has taken steps to adjust its framework for housing

nance to restrain the growth of public securitization.

We conclude with a discussion of policies that could

be considered to reinvigorate private securitization in

Canada.

2 On 11 December 2015, the government announced changes to its public

securitization programs. The estimates in this report are based on the

guarantee fees that existed before the 11 December announcement.

See the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation press release at

http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/corp/nero/nere/2015/2015-12-11-0900.cfm.

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

39

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

Mortgage Securitization in Canada:

The Context

Institutional background

The federal government supports housing nance

in Canada through mortgage insurance and public

securitization programs.

3

Federally regulated lenders

are required to obtain mortgage insurance on loans in

which the homebuyer has made a down payment of less

than 20 per cent of the purchase price.

4

Mortgage insur-

ance is provided by the Canada Mortgage and Housing

Corporation (CMHC) and private insurers; insurance

from both sources is guaranteed by the government,

although not to the same degree.

5

In Table 1, we illustrate the interaction between mort-

gage insurance and securitization in Canada. Public

securitization is provided through the NHA MBS and

Canada Mortgage Bond (CMB) programs, both admin-

istered by CMHC (Box 1 provides further detail on these

types of securities). Both programs use only insured

mortgages; public securitization of uninsured mortgages

does not exist in Canada.

Private-label securitization has existed in Canada since

1985. To reduce taxpayer exposure and encourage

development of private mortgage markets, the govern-

ment announced its intention to prohibit the use of

insured mortgages as collateral in non-CMHC securi-

tization vehicles.

6

To date, private-label securitization of

3 The government also supports housing nance through other means,

including tax credits and RRSP withdrawals for rst-time home buyers.

4 Low-ratio mortgages (with down payments greater than 20 per cent) can

also be insured by CMHC and private insurers with portfolio or trans-

actional insurance. See Crawford, Meh and Zhou (2013) for a detailed

discussion of the Canadian mortgage market.

5 CMHC mortgage insurance has a 100 per cent public guarantee, while for

private insurers it is only 90 per cent. The government guarantee is activated

when the insurer fails to honour its commitment to the lender.

6 See Government of Canada (2015).

uninsured mortgages primarily consists of short-term

asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP)

7

and some

longer-term residential mortgage-backed securities

(RMBS). New issuance of RMBS has been close to non-

existent in Canada in recent years.

Covered bonds are another important source of funding

that used to be backed by insured mortgages. However,

in April 2012, the federal government announced a regis-

tered covered bond framework to be administered by

CMHC. Under the framework, the bonds are only backed

by uninsured mortgages. Subject to the prudential limit

established by the Ofce of the Superintendent of Financial

Institutions (OSFI), an FI can have outstanding covered

bonds of no more than 4 per cent of its total assets. To

date, under the framework, total issuance stands at over

$70 billion. Covered bonds are an alternative to public and

private securitization as a source of funding for FIs.

8

Table 2 compares the level of government involvement in

the mortgage market across Canada, the United States,

the United Kingdom and Australia. Compared with the

United States, Canada exhibits a higher level of govern-

ment involvement in mortgage insurance but a lower

level of involvement in mortgage securitization. Australia

has an active private mortgage insurance system with no

public support, while the United Kingdom’s private mort-

gage insurance system is limited. The United Kingdom

also has temporary public mortgage insurance programs

created by the government during the nancial crisis. The

table also indicates that the four countries have broadly

similar rates of home ownership.

7 About 20 per cent of the underlying residential mortgages backing ABCP are

uninsured at present.

8 See the 2015 report by the C.D. Howe institute, “How to Make the World

Safe for (and from) Covered Bonds” (Poschmann 2015).

Table 2: Cross-country comparison (per cent)

Canada

United

States

United

Kingdom Australia

Share of public

mortgage

insurance

58.0 14.0 0.4 0

Share of public

securitization

34.0 55.0 0.0 0

Home-ownership

rate

67.6 65.1 64.6 67

Note: Public insurance in Canada is the insurance-in-force, i.e., the total amount

of outstanding loan balances covered by mortgage loan insurance policies by

CMHC and private insurers. For the United States, public insurance relates to

Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Affairs loans, which are insured

by the federal government. For the United Kingdom, it is the NewBuy Guaran-

tee and the Help to Buy programs. Share of public insurance is to outstanding

mortgage debt as of 2013 (for the United Kingdom, as of 2014). Shares of public

securitization to outstanding mortgage debt for Canada and the United States

are as of 2014. U.S. data are from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets

Association and the Federal Reserve Board and are based on the ratio of agency

MBS outstanding to total mortgage credit. See Chart 1-A for the Canadian data.

Home-ownership rates are as of 2013 except for Australia (2011).

Source: Bank of Canada

Table 1:

Types of residential mortgage securitization

inCanada

Underlying mortgage type

Securitization

Insured Uninsured

Public National Housing Act

Mortgage-Backed

Securities and Canada

Mortgage Bonds

Does not exist

Private-label Intention to disallow

announced

Asset-backed

commercial paper and

residential mortgage-

backed securities

Note: Covered bonds are a direct obligation of nancial institutions issuing the

bonds and, hence, are not considered securitizations. Investors have recourse to

the covered pool in the event of issuer default.

Source: Bank of Canada

40

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

Box 1

National Housing Act Mortgage-Backed Securities and Canada Mortgage Bonds

The NHA MBS Program, introduced in 1987, allows fi nan-

cial institutions (FIs) to issue mortgage-backed securities

(MBS) that are backed by pools of residential mortgages

insured under the National Housing Act. NHA MBS investors

are not subject to payment risk or the underlying mortgage

credit risk, owing to the Canada Mortgage and Housing

Corporation’s (CMHC) timely payment guarantee of interest

and principal, as well as the insurance on the underlying

mortgages. Before 2015, the annual cost of guaranteeing

the timely payment on a typical 5-year NHA MBS was four

basis points.

1

Although investors face no credit risk, they are

exposed to prepayment risk on the underlying mortgages

that o er amortizing monthly cash fl ows. The majority of

NHA MBS are fi xed rate and are issued for a 5-year term,

refl ecting the popularity of the 5-year fi xed-rate mortgage.

Since 2001, NHA MBS could be sold to the Canada Housing

Trust (CHT), which funds these purchases by issuing Canada

Mortgage Bonds (CMB). Similar to NHA MBS, CMB o er

investors a timely payment guarantee; the guarantee fee

is paid up front by the participating fi nancial institution.

Approximately half of newly issued CMB are fi xed rate for

5-year terms. Unlike NHA MBS, the CMB Program converts

monthly amortizing cash fl ows into typical bond-like payments

(i.e., semi-annual or quarterly coupon payments and a fi nal

full principal payment). Thus, CMB appeal to a much broader

investor base, and funding can be achieved at a relatively lower

cost than for NHA MBS.

The public policy objectives of the NHA MBS and CMB

programs are to “contribute to the e cient functioning,

competitiveness, and stability of the housing fi nance

system by helping ensure lenders and, in turn, borrowers

have access to a reliable source of funding for residential

mortgages regardless of economic cycles and market con-

ditions” (CMHC 2014). These objectives address the goal of

providing a reliable funding source throughout the economic

cycle and supporting competition in mortgage lending by

supplying cost-e cient funding to small lenders that have

limited access to alternative sources. Figure 1-A provides

breakdowns of the total amount of outstanding NHA MBS of

approximately $425billion by usage and issuer.

1 The cost of the annualized guarantee fee is higher than four basis points when

the average life of the 5-year NHA MBS is less than fi ve years. If, for example, the

average life were three years, the cost would be roughly seven basis points.

File information

(for internal use only):

Figure 1 -- EN.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Note: FRFIs are federally regulated nancial institutions. Retained NHA MBS

are reported as pooled but unsold by FRFIs. Syndicated NHA MBS are not sold

only by the bank that created them, but rather by a syndicate of dealers. “Other”

captures all remaining NHA MBS.

Sources: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and Of ce of the

Superintendent of Financial Institutions

Sold to the CMB Program

Retained by FRFIs (NHA MBS pooled and unsold)

Syndicated NHA MBS

Other

Big Six banks

Non-Big Six banks

Figure 1-A:

Composition of outstanding National Housing

Act Mortgage-Backed Securities as of June 2015

By usage, Can$ billions

By issuer, Can$ billions

$213

$172

$24

$15

$305

$119

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

41

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

Market developments

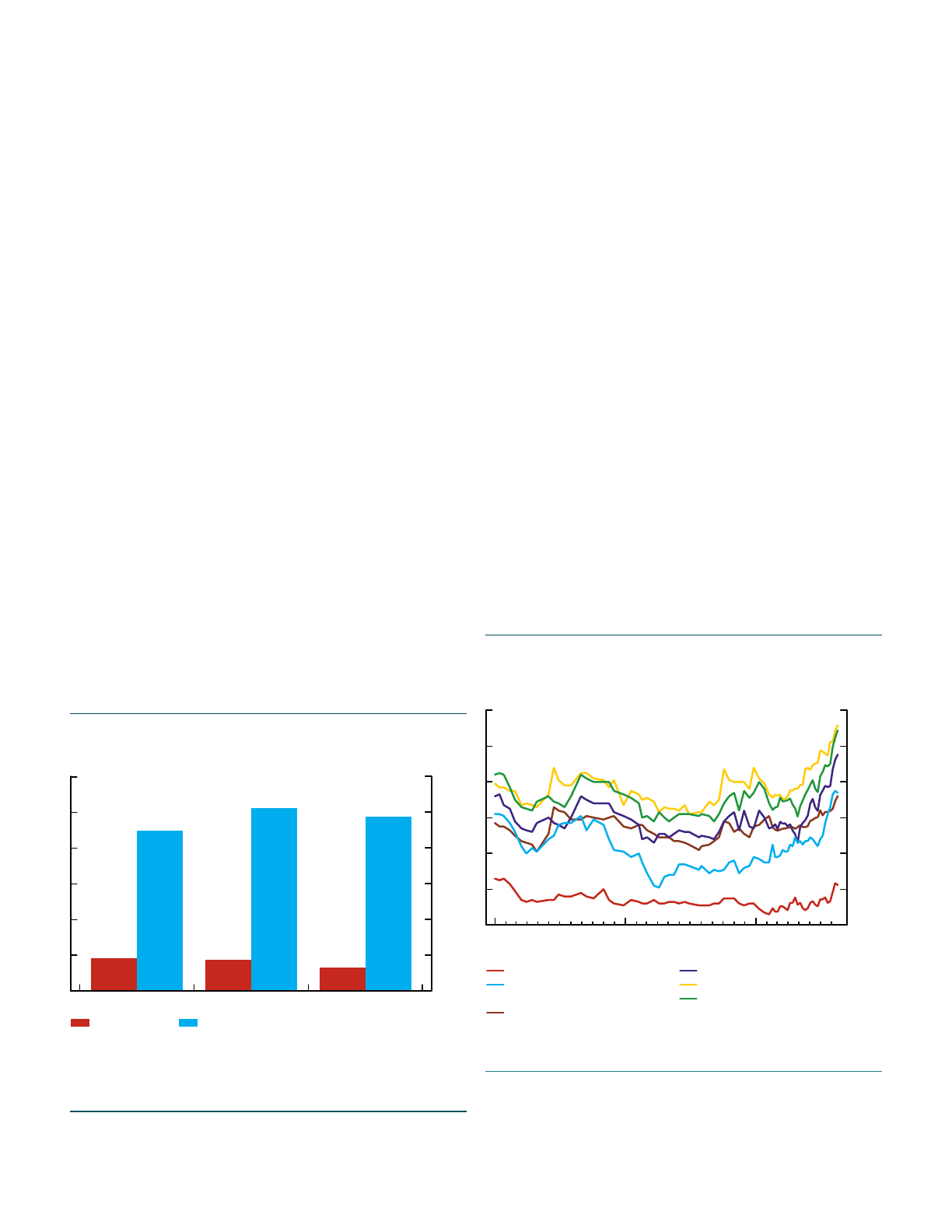

Chart 1-A shows the substantial rise in the share of

outstanding securitized mortgage debt. In 2000, only

about 10 per cent of the outstanding mortgage debt was

securitized, and half of that was through private pro-

grams. By 2015, about a third of the outstanding mort-

gage debt was securitized, almost all through public

programs. Not surprisingly, mortgage credit in Canada

has tended to move directionally with public securitiza-

tion, as is evident in Chart 1-B, which compares the

annual growth rates for the two series.

The rapid expansion of public securitization is espe-

cially evident in the period between 2008 and 2010, in

response to the Insured Mortgage Purchase Program,

which allowed mortgage lenders to pool insured mort-

gages into NHA MBS and sell them to CMHC to obtain

additional liquidity during the nancial crisis.

9

Currently,

the stock of public securitization continues to increase,

although at a slower pace, in part because of limits

imposed by the government on NHA MBS and CMB

issuance (Chart 2).

10

Before the nancial crisis, there was also an active

market for ABCP and, in 2006, approximately $20billion

of the underlying assets were residential mortgages

(some of which were insured). The non-bank-sponsored

ABCP market, which mainly invested in complex credit

derivatives known as collateral debt obligations that

were backed by U.S. subprime mortgages, experienced

severe disruptions in the summer of 2007, since issuers

were unable to roll over their short-term debt.

11

Since

then, the ABCP market has contracted substantially

and, as of June 2015, only about $10 billion of the

outstanding securities were backed by residential mort-

gages (Chart 3).

Several factors explain the rising share of public securi-

tization in Canada from both the demand and supply

perspectives. For FIs, CMB are a cost-effective funding

9 A description of the program is available at http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/

lop/researchpublications/prb0856-e.htm.

10 While annual issuance of CMB since 2013 has been held to $40 billion a

year, the annual issuance of NHA MBS was lowered to $80 billion a year for

2014 and 2015 (from $85 billion in 2013).

11 Kamhi and Tuer (2007) discuss the collapse of the non-bank ABCP market

in Canada.

File information

(for internal use only):

1-A.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Sources: Canada Mortgage and

Housing Corporation and Statistics Canada Last observation: June 2015

Private Public

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015

%

Chart 1-A:

Ratio of outstanding securitization to residential

mortgagedebt

File information

(for internal use only):

1-B.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Sources: Canada Mortgage and Housing

Corporation and the Bank of Canada Last observation: December 2014

Public securitization (left scale) Mortgage debt (right scale)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

%

%

Chart 1-B:

Growth rates of outstanding public securitization

and residential mortgage debt

File information

(for internal use only):

2.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Source: Canada Mortgage

and Housing Corporation Last observation: June 2015

Canada Mortgage Bonds NHA Mortgage-Backed Securities

100

200

300

400

500

1987 1991 1995 1999 2003 2007 2011 2015

0

Can$ billions

Chart 2:

Outstanding public mortgage securitization

42

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

tool, especially for smaller institutions that do not have

a branch network of deposits and lack alternative

funding sources. As well, from a regulatory perspec-

tive, NHA MBS qualify (as do CMB) as high-quality

liquid assets (HQLA) under the terms of the Basel III

Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR).

12

As of June 2015, about

40 per cent of the outstanding stock of NHA MBS was

retained by federally regulated FIs, which could help

them meet the LCR requirement.

For NHA MBS and CMB, investors also benet from a

timely payment guarantee (offered by the government

through CMHC for a fee, called the guarantee fee) on the

securities’ interest and principal. This enhances demand

for the securities, since investors do not face credit risk

or uncertainty as to the timing of cash ows from the

securities. In addition, the timely payment guarantee

allows NHA MBS and CMB to be government securities

from a credit perspective, which enhances their attract-

iveness to investors.

Quantifying the Impact of

Government-Supported Securitization

In this section, we examine the potential impacts

of public securitization in Canada, specically, the

benets that accrue to the nancial system and

12 Under Basel III, a bank needs to have an adequate stock of unencumbered

HQLA that can be converted easily and immediately in private markets

into cash to meet their liquidity needs for a 30-calendar-day liquidity

stress scenario. The LCR is the ratio of the stock of HQLA to total net cash

outows. The standard requires that, absent a situation of nancial stress,

the value of the ratio should be no lower than 100 per cent (i.e., the stock

of HQLA should at least equal total net cash outows). During a period of

nancial stress, however, institutions may use their stock of HQLA, thereby

causing the ratio to fall below 100 per cent.

FIs, and attempt to quantify two of them: the cost-

effectiveness of funding and the regulatory benet of

meeting the LCR.

13

Canadian mortgage lenders and borrowers benet

from the certainty and availability of funding provided

by CMHC securitization, especially through the CMB

Program. The regular schedule of CMB issuance and

relatively steady issuance volumes on a quarterly basis

provide lenders with certainty of cost-effective funding,

which is valuable for business planning purposes.

That value was highlighted in 2008 during the nancial

crisis, when access to market funding for FIs world-

wide became severely restricted. During that time, the

CMB Program continued to issue bonds on its regular

schedule, in increased volumes, albeit at wider spreads.

This is shown in Chart 4, which reports indicative

(expected) spreads for new issuances of NHA MBS and

CMB over 5-year Government of Canada bonds.

Another important benet of government-backed securi-

tization programs is that they limit severe procyclical

contractions in the extension of mortgage credit during

a crisis, when access to funding may be impaired. For

example, between 2008 and 2014, the average annual

growth rate in outstanding mortgage credit in Canada

was 6 per cent, whereas in the United States, mortgage

13 It is challenging to disentangle the benets of mortgage insurance from

those of securitization. For that, we would need a type of mortgage

securitization that does not exist in Canada, one in which the government

provides a timely payment guarantee on MBS that are backed by uninsured

mortgages (Table 1). Evidence from the United States suggests that in the

1990s and 2000s, the difference in interest rates for borrowers between

mortgages that were more easily securitizable and those that were not was

up to 24 basis points (Adelino, Schoar and Severino 2012).

File information

(for internal use only):

3.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Source: Dominion Bond Rating Service Last observation: June 2015

Total residential mortgages

0

5

10

15

20

25

2006

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Can$ billions

Chart 3:

Outstanding residential mortgages funded through

asset-backed commercial paper

File information

(for internal use only):

4.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Source: Royal Bank of Canada Last observation: September 2015

Canada Mortgage Bonds National Housing Act

Mortgage-Backed Securities

0

50

100

150

200

2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

Basis points

Chart 4:

Spreads of NHA MBS and CMB over 5-year

Government of Canada bonds

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

43

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

credit contracted by approximately 2 per cent per year,

even after accounting for the increased issuance of MBS

by government-sponsored enterprises. While there were

clearly other important factors at play, public securitiza-

tion in Canada helped support growth in mortgage

credit during this period. Finally, Canadian banks also

use NHA MBS and CMB as collateral in repo trans-

actions. Gravelle, Grieder and Lavoie (2013) document

that these securities account for about 20 per cent of

repo collateral (classied as obligations of Crown cor-

porations). Further, FIs can pledge NHA MBS and CMB

in the Large Value Transfer System, which allows them

to use other securities for other purposes.

The cost-eectiveness of public securitization

Canadian institutions use a variety of sources to meet their

funding needs, with the mix depending on the cost-effect-

iveness of the options. Funding sources for the Big Six

banks include wholesale instruments such as short-term

debt and senior unsecured bonds, covered bonds backed

by pools of mortgages, securitized issuances (including

the NHA MBS and CMB programs and vehicles backed

by credit card receivables), and retail and corporate

deposits. Funding by the large Canadian banks may also

take place in a variety of currencies, in particular for senior

unsecured bonds and covered bonds, with the foreign

currency proceeds typically swapped back to Canadian

dollars. Small lenders are more limited in their funding

options and rely to a greater extent on the NHA MBS and

CMB programs for funding, as indicated in Chart 5.

We estimate the cost-effectiveness of funding from the

NHA MBS and CMB programs by comparing their cost

of funds with the cost of the next-cheapest source of

long-term wholesale funding. We measure how much

funding costs for lenders would rise if the NHA MBS and

CMB programs did not exist.

This approach follows the methodology employed by

CMHC’s evaluation of the CMB Program, which was

prepared by KPMG and released in 2008.

14

Although the

approach allows us to compare the cost-effectiveness

of the NHA MBS and CMB programs, its drawback

is that the methodology requires some simplifying

assumptions; namely, that the funding cost of the next-

cheapest alternative would not increase if the programs

ceased, that funding in sufcient size would be avail-

able from the alternative, and that CMB and NHA MBS

funding is raised only at the 5-year term.

Since funding costs on the cheapest alternative change

over time, as indicated in Chart 6, we report a range for

the funding advantage of CMB and NHA MBS in Table 3,

which is based on the chart.

15

The table indicates that,

over the sample period, the average cost advantage for

a Big Six bank from the CMB Program relative to the

next-best alternative was about 40 basis points, and the

relative benet of NHA MBS was about 11 basis points.

14 Canada Mortgage Bonds Program Evaluation (KPMG 2008).

15 Funding costs are based on biweekly dealer quotes between January 2013

and September 2015 and include guarantee and syndication fees. Guarantee

fees on NHA MBS and CMB are based on the fee level before 1 April 2015.

Funding costs are swapped back to Canadian dollars and expressed in terms

of a spread to the 3-month Canadian-Dollar Offered Rate.

File information

(for internal use only):

5.indd

Last output: 03:21:35 PM; Mar 14, 2012

Note: Ratios are as of June of each year.

Sources: Of ce of the Superintendent

of Financial Institutions and Canada Mortgage

and Housing Corporation Last observation: June 2015

Big Six banks Small lenders

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2013 2014 2015

%

Chart 5:

Ratio of outstanding National Housing Act

Mortgage-Backed Securities to total liabilities

File information

(for internal use only):

6.indd

Last output: 01:45:37 PM; Nov 13, 2015

Note: CDOR = Canadian-Dollar Offered Rate

Source: Dealer quotes Last observation: September 2015

Canada Mortgage Bonds

National Housing Act

Mortgage-Backed Securities

US$ covered bonds

Can$ covered bonds

US$ senior unsecured debt

Can$ senior unsecured debt

2013 2014 2015

-10-10

10

30

50

70

90

110

Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan Apr Jul

Basis points

Chart 6:

Indicative 5-year all-in funding costs

(as spread to3-month CDOR)

44

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

For comparison, the KPMG report, which evaluated only

the CMB Program over the 2001–06 period, concluded

that the average cost advantage of that program over

the next-best alternative was about 18 basis points.

Estimating the cost advantage of NHA MBS and CMB as

funding sources for small mortgage lenders is more dif-

cult. On the one hand, the cost of CMB funding is higher

for lenders who require third-party assistance in the

CMB swap and sourcing of replacement assets backing

CMB issues, reducing the relative cost advantage of

CMB funding.

16

On the other hand, the cost of alternative

sources of wholesale funding for small lenders is gener-

ally higher than that of the Big Six banks, increasing the

relative cost advantage of CMB funding. In addition, to

the extent that small lenders meet a higher proportion

of their total funding needs through the NHA MBS and

CMB programs than do the Big Six banks (as indicated

in Chart 5), the programs provide a greater relative

advantage to small lenders.

Given the overall supply constraint on CMB and NHA

MBS, small lenders also benet from the allocation

methodology used by CMHC to distribute NHA MBS

issuance and CMB funding among FIs. Available funding

is allocated equally to all FIs, regardless of their size

or requests for funding. As a result, small lenders are

able to access the public securitization programs for a

greater relative share of their funding needs, providing

more-stable funding sources and helping them to com-

pete against other mortgage lenders.

One can roughly estimate the alternative private funding

costs for small lenders by considering an RMBS issuance

completed in 2014. The weighted average spread of all

the tranches issued in the market was about 40basis

points over NHA MBS. Assuming that the averages from

Table 3 are representative, the issuer paid its RMBS

investors about 70 basis points more than what it would

have paid for CMB funding.

16 Lenders participating in the CMB Program must substitute maturing NHA

MBS sold to the Canada Housing Trust with replacement assets and must

engage in a swap with CHT where they exchange the interest ows on CMB

issues with those on the securities backing the CMB.

Based on the current outstanding stock of NHA MBS

and CMB, and assuming that their relative funding

cost advantage is the same across all institutions, we

estimate the aggregate annual funding benet of these

programs to be about $870 million for all FIs that access

the programs.

17

The use of public securitization to meet the

Liquidity Coverage Ratio

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision requires

banks to have (at a minimum) sufcient HQLA to cover

stressed cash outows over a 30-day period (BCBS

2013). The total amount of HQLA distinguishes between

the highest-quality liquid assets (Level 1 HQLA) and

those that are somewhat less liquid (Level 2 HQLA).

While there is a cap on the amount of Level 2 assets

(they can comprise no more than 40 per cent of total

HQLA), there is no cap and no haircut on Level 1 assets.

In this sense, they can be held in unlimited amounts for

LCR purposes (i.e., total HQLA requirements can be met

entirely by any specic Level 1 asset).

18

Both NHA MBS and CMB qualify as Level 1 assets. They

have the added advantage of carrying a zero risk-weight

capital requirement because they are government guar-

anteed.

19

However, NHA MBS are an attractive instrument

for FIs to hold for the LCR because they are readily con-

vertible from mortgages on their books and have a higher

yield than Government of Canada bonds and CMB.

The advantage of using NHA MBS to meet the LCR

requirement can be estimated by considering the cost

of holding the next-cheapest alternative, provincial

bonds—which also qualify as Level 1 assets. We com-

pare the cost of converting insured mortgages to a

5-year NHA MBS held for the LCR versus buying provin-

cial bonds for the LCR by funding the purchase through

the cheapest wholesale funding instrument, covered

bonds, on the assumption that the NHA MBS and CMB

programs did not exist.

17 As of June 2015, the stock of outstanding CMB totalled $213 billion,

whereas the estimated outstanding stock of syndicated NHA MBS stood at

about $15 billion. Multiplying the outstanding amounts of these instruments

by their respective average cost advantages (40 basis points and 11 basis

points, respectively) yields a total benet of about $870million.

18 For further discussion on the Basel III liquidity standards, see Gomez and

Wilkins (2013).

19 According to OSFI, because NHA MBS are guaranteed by CMHC, they receive

a zero per cent risk weight in recognition of the fact that obligations incurred

by CMHC are legal obligations of the Government of Canada. See http://www.

os-bsif.gc.ca/eng/-if/rg-ro/gdn-ort/gl-ld/Pages/CAR_chpt3.aspx.

Table 3: All-in funding cost advantage of Canada Mortgage

Bonds and NHA Mortgage-Backed Securities versus the

next-cheapest private alternative (basis points)

Minimum Average Maximum

CMB 28 40 51

Syndicated

NHA MBS

0 11 28

Source: Bank of Canada

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

45

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

Table 4 indicates that the benet of NHA MBS for LCR

purposes differs, based on the amount issued.

20

For the

rst $6 billion, FIs would save, on average, 22 basis points,

and for any amount issued above $6billion, FIs would save

about 12 basis points. This means that, for FIs in aggre-

gate, the benet for each $100 billion of NHA MBS held for

LCR purposes amounts to at least $120 million annually.

21

Potential Implications of

Government-Supported Programs

Although benets accrue to mortgage lenders from

accessing CMHC securitization programs, there are also

risks associated with these programs. There is the risk

that CMHC will be called upon under the timely payment

guarantee to meet interest and/or principal payments on

NHA MBS or CMB issues. CMHC reserves for this risk

by charging lenders guarantee fees, and it holds capital

against its securitization exposures of about $1.6 billion

(year-end 2014). There are, however, other potential

vulnerabilities and risks associated with public securiti-

zation from a nancial stability perspective that may not

be fully incorporated in the level of guarantee fees. We

review those below.

Impact on the supply of mortgage credit

Since lenders can securitize mortgages under the public

securitization programs in a cost-effective manner,

they may overextend mortgage credit and underinvest

in other productive assets (such as small business

loans). The latter may occur because mortgage-backed

20 The cost of 5-year NHA MBS is based on the guarantee fee schedule as

of 1 April 2015. For the rst $6billion, the upfront guarantee fee was set at

0.30 per cent, or 10 basis points annually, assuming that the average life of

NHA MBS is three years. Similarly, for any amount above $6 billion, the fee

was set at 0.60 per cent, or 20 basis points annually. We exclude the cost

of insuring the mortgages. Spread levels are relative to the 3-month CDOR

and are based on average biweekly dealer quotes between January 2013

and September 2015. We use 5-year Ontario bonds as the provincial proxy.

21 Holding CMB for collateral purposes is more expensive than holding prov-

incial bonds, given the relatively lower yield on CMB. However, the liquidity

of CMB may make them an attractive security for LCR purposes.

funding for FIs through public securitization is more

cost-effective and stable than non-mortgage-backed

funding, creating an incentive to extend more mortgage

credit than would occur without public securitization. An

increase in mortgage credit could lead to more lever-

aged households and elevated house prices.

While public securitization programs may support

competition, they may also increase vulnerabilities in

the nancial system by inuencing the business models

of mortgage lenders. For example, mortgage nance

companies (MFCs) are important participants in the

residential mortgage market. MFCs typically underwrite

and service insured mortgages sourced from brokers.

They tend to sell a large proportion of their mortgage

loans to federally regulated nancial institutions (FRFIs),

which may use them in CMHC securitization programs

for funding or regulatory purposes, or into CMHC

securitization programs. In this way, MFCs rely to a

considerable extent on funding from public securitiza-

tion programs. Without these programs, it is not clear if

MFCs’ other sources of funding, which are less stable

than deposits (e.g., syndicated lines of credit from

banks), would be reliable and large enough to support

their mortgage activities.

MFCs are less-regulated lenders (i.e., they are not dir-

ectly regulated by OSFI), although they must abide by

residential mortgage underwriting guidelines for FRFIs.

22

Limited available data also suggest that MFCs are highly

leveraged, leaving them less able to manage liquidity

and maintain income following an increase in mortgage

defaults (although mortgage insurance limits the eventual

losses). The participation of MFCs (supported by public

securitization programs) in the residential mortgage

market increases competition, but more transparency

and analysis are needed to better understand their

business models and their potential impact on nancial

system risk (see the June 2015 Financial System Review).

Use of securities for regulatory requirements

As noted earlier, since NHA MBS (and CMB) qualify as

Level 1 assets, FIs can use them in unlimited amounts to

meet the LCR requirement. As of year-end 2014, about

$184 billion in NHA MBS were retained on-balance-sheet,

mainly by the Big Six banks, and NHA MBS represent the

most effective asset for FIs to use for LCR purposes.

From a public policy perspective, when the government

was restricting the use of portfolio mortgage insurance

to limit public exposure to housing nance, it noted that

“[T]hese measures will restore taxpayer-backed portfolio

22 MFC-originated mortgages purchased by FRFIs must conform to OSFI

Guideline B-20, and MFCs are motivated to follow the principles set out for

mortgage insurers in OSFI Guideline B-21 so that mortgages can qualify for

CMHC securitization programs.

Table 4:

The cost advantage of adhering to the Liquidity

Coverage Ratio with NHA Mortgage-Backed Securities vs.

provincial debt

Annual cost of creating

NHA MBS

For the rst $6 billion: 10 basis points

Any amount above $6 billion: 20 bps

Cost to hold provincial bond

for the LCR

Issue covered bond

Return on provincial bond

Total holding cost

Canadian-Dollar Offered Rate + 44 bps

CDOR + 12 bps

32 bps

Cost differential for the rst $6B: 22 bps

for any amount above $6B: 12bps

Source: Bank of Canada

46

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

insurance to its original purpose of allowing access to

funding for mortgage assets” (Government of Canada

2013).

Effective 1 April 2015, CMHC increased the guarantee

fees applied to NHA MBS for each FI and, in particular,

doubled the fees on issuances above $6 billion.

23

In addi-

tion to encouraging the development of alternative funding

options in the private market, the differential guarantee fee

structure may reect the variety of ways in which FIs use

NHA MBS. It is also consistent with the program’s stated

objective of promoting competition, since smaller lenders,

who are more likely to use NHA MBS for funding and

demand less than the $6 billion cut-off, will be paying lower

fees than FIs that demand larger amounts.

Eect on alternative funding models

Alternative funding vehicles, such as private-label securi-

tization markets, can be used to fund mortgages and

transfer and diversify risk in a way that would benet

the real economy (BoE and ECB 2014). In Canada, the

availability of low-cost publicly guaranteed funding may

reduce the incentive for FIs to explore the development

of alternative mortgage funding vehicles, namely private-

label mortgage securitization. For example, during its

review of the CMB Program, KPMG interviewed repre-

sentatives of the big ve banks, which indicated that “in

the absence of the CMB program, private securitization

vehicles would have been issued, probably by the big

ve banks as single issuers and possibly as multi-seller

vehicles for smaller players” (KPMG 2008, p. 31).

It is not certain, however, that FIs would develop alterna-

tive funding models if access to public securitization

programs were reduced. FIs could choose to utilize

existing funding sources to a greater extent in situations

where the benets of the alternative models are uncer-

tain, set-up challenges are high and their additional

funding needs may not be large.

24

Private securitizations

may also be limited, since they cannot be backed by

insured mortgages. As such, the development of private

vehicles depends in part on the growth rate of uninsured

mortgage credit and the extent to which it outstrips FIs’

existing funding sources.

23 See http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/hoclincl/mobase/upload/

MBS_Advice_Guarantee_Fee_Increase-Dec-1-2014.pdf. For the issuance

of 5-year NHA MBS of up to $6 billion, the upfront guarantee fees increased

from 0.20per cent to 0.30 per cent. For any amount above $6 billion, the

fee was set at 0.60 per cent. For the issuance of a 5-year CMB, the guar-

antee fee was raised from 0.20 per cent to 0.40 per cent.

24 One alternative model is covered bonds, which are limited to four per cent

of the total applicable assets of the deposit-taking institution.

Policy Options to Promote Private

Securitization

The government could continue to reduce public

involvement in the housing market by adopting policy

measures to promote a private-label securitization

market.

25

In addition, the government could consider

changes to public securitization, which could take the

form of some or all of the following: further increases in

the cost to access CMHC programs, additional reduc-

tions in the issuance caps under CMHC programs or

restrictions on the eligibility of lenders able to participate

in the programs.

Fostering a private-label mortgage securitization market

in Canada could help to achieve a rebalancing of

private and public securitization. Such a market could

benet the economy by helping lenders fund assets

and diversify risks (Schembri 2014; BoE and ECB 2014).

In that respect, the Bank of Canada announced that,

as of April 2015, term asset-backed securities of high

quality, including residential mortgage-backed secur-

ities, would be considered as eligible collateral for the

Standing Liquidity Facility (SLF).

26

Other measures that

could promote an appropriate framework for private-

label mortgage securitization include principles for

eligible collateral, reporting requirements and structure

standardization.

Some steps to reduce public securitization have already

been put in place. As part of its 2014 budget, the federal

government announced that it would implement meas-

ures to reduce taxpayer exposure to the housing sector

and increase market discipline in residential lending.

For example, while the annual issuance of CMB since

2013 has been kept at $40 billion a year, the annual

issuance of NHA MBS was lowered to $80 billion a

year for 2014 and 2015 (from $85 billion in 2013) (GoC

2014). And, as mentioned earlier, the government also

raised the guarantee fees on NHA MBS and CMB as

of 1 April 2015, and announced further changes on

11 December 2015 (effective July 2016), to encourage

the development of alternative funding options in the

private sector.

Going forward, the government has other options in

addition to a further increase in guarantee fees or a

reduction in issuance caps on these securities. It could

also consider an auction-based mechanism whereby

the right to issue NHA MBS and the allocation of funding

under the CMB Program could be distributed based on

bidding by nancial institutions. As such, an institution

in need of funds would be willing to offer a higher price.

25 Another alternative could be to expand the use of covered bonds as a

source of mortgage funding. See Poschmann (2015).

26 For a detailed description of this change, see http://www.bankofcanada.

ca/2015/01/planned-changes-assets-eligible-collateral/.

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

47

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015

This approach might be appropriate, since prices would

more accurately reect demand and the riskiness of

the lenders.

27

However, this mechanism could impair

the competitive position of smaller lenders on a relative

basis.

Another approach could be to lower the size of the CMB

Program and dedicate it to small lenders, recognizing

that small lenders do not enjoy the same access to

funding as large lenders. An alternative that is less

distortionary than quantity constraints is for the govern-

ment to consider setting higher fees for large lenders

that participate in the programs. In general, both options

would be consistent with the policy objectives of the

CMHC securitization programs and with the philosophy

that government intervention in the market should take

place only in cases of market failure.

27 An institution that needs funding will offer a higher yield than an institution

with less-pressing needs at the time it submits its auction offer to CMHC.

Conclusion

The public “footprint” in the Canadian mortgage securi-

tization market has increased in recent years. The public

role provides stable mortgage funding for FIs and pro-

motes competition from small lenders in that market. It

also has consequences for the allocation of savings, the

business models chosen by small lenders and the cost

of regulatory compliance by banks.

This increase in the public footprint has led to a discus-

sion about the government’s role in housing nance

from a range of perspectives, including that of nancial

stability. The government has implemented a number of

measures in recent years to reduce the public’s involve-

ment. Further discussion and analysis of potential policy

options, including those to promote private mortgage

securitization, would be useful.

References

Adelino, M., A. Schoar and F. Severino. 2012. “Credit

Supply and House Prices: Evidence from Mortgage

Market Segmentation.” NBER Working Paper

No.17832.

Bank of England and the European Central Bank (BoE

and ECB). 2014. “The Case for a Better Functioning

Securitisation Market in the European Union.” Joint

Discussion Paper, May.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). 2013.

“Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Liquidity

Risk Monitoring Tools.”

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC).

2014. Canadian Housing Observer 2014.

Crawford, A., C. Meh and J. Zhou. 2013. “The

Residential Mortgage Market in Canada: A

Primer.” Bank of Canada Financial System Review

(December): 53–63.

Gomes, T. and C. Wilkins. 2013. “The Basel III Liquidity

Standards: An Update.” Bank of Canada Financial

System Review (June): 37–43.

Government of Canada (GoC). 2013. Economic Action

Plan 2013. March.

Government of Canada (GoC), 2014. Economic

Action Plan 2014. February.

—

. 2015. Economic Action Plan 2015. April.

Gravelle, T., T. Grieder, and S. Lavoie. 2013. “Monitoring

and Assessing Risks in Canada’s Shadow Banking

Sector.” Bank of Canada Financial System Review

(June): 55–63.

Kamhi, N. and E. Tuer. 2007. “The Market for Canadian

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper, Revisited.” Bank

of Canada Financial System Review (June): 13–16.

KPMG LLP. 2008. Canada Mortgage Bonds Program

Evaluation. Available at www.cmhc.ca/en/hoclincl/

in/camobo/upload/CMB-Evaluation-Jun08.pdf.

Poschmann, F. 2015. “How to Make the World Safe for

(and from) Covered Bonds.” C. D. Howe Institute

E-Brief. Available at http://www.cdhowe.org/

how-make-world-safe-and-covered-bonds.

Schembri, L. L. 2014. “Housing Finance in Canada:

Looking Back to Move Forward.” National Institute

Economic Review 230 (1): R45–R57.

48

RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION IN CANADA: A REVIEW

BANK OF CANADA • FINANCIAL SYSTEM REVIEW • DECEMBER 2015