November 2021

◆

Volume 104, Number 5 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 461

Altered mental status (AMS) can present as

changes in consciousness, appearance, behavior,

mood, aect, motor activity, or cognitive func-

tion.

1-3

Recent changes are the focus of this arti-

cle and are approached dierently than chronic

changes. Recent changes occur within seconds to

days and usually pose a more immediate threat

to a patient’s well-being than chronic changes.

2-4

AMS is common and is estimated to account

for 5% of adult emergency department encoun-

ters.

5

Older people are especially susceptible,

as evidenced by their high rates of delirium

(Table 1).

6

Additionally, AMS is associated with

poor patient outcomes, especially when recogni-

tion is delayed.

7,8

e dierential diagnosis for AMS is broad. A

history and physical examination are the corner-

stones of diagnosis, and their ndings guide diag-

nostic testing. Preventive measures can decrease

incidence and are important to use in patients at

high risk. e goal of treatment is to correct the

precipitating cause of the AMS.

2,3,9-11

Causes of Recent AMS

Causes of recent AMS include primary central

nervous system insults, systemic infections, met-

abolic disturbances, toxin exposure, medications,

chronic systemic diseases, and psychiatric condi-

tions (Table 2).

2-4,9,10

Although a single abnormal-

ity may cause the alteration in mental status (e.g.,

opiate overdose), oen the cause is multifactorial

(e.g., dehydration, constipation, high-risk medi-

cation use).

2-4,9,10

Among the most common and important pre-

sentations of AMS is delirium, especially in older

adults who are hospitalized.

6,9

e hallmarks

of delirium are acute, uctuating changes in

Recent-Onset Altered Mental Status:

Evaluation and Management

Brian Veauthier, MD; Jaime R. Hornecker, PharmD; and Tabitha Thrasher, DO

University of Wyoming Family Medicine Residency Program, Casper, Wyoming

Additional content at https:// www.aafp.org/afp/2021/1100/

p461.html.

CME

This clinical content conforms to AAFP criteria for

CME. See CME Quiz on page 449.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial aliations.

Potential precipitating factors for the recent onset of altered mental status (AMS) include primary central nervous system

insults, systemic infections, metabolic disturbances, toxin exposure, medications, chronic systemic diseases, and psychiat-

ric conditions. Delirium is also an important manifestation of AMS, especially in

older people who are hospitalized. Clinicians should identify and treat revers-

ible causes of the AMS, some of which require urgent intervention to minimize

morbidity and mortality. A history and physical examination guide diagnostic

testing. Laboratory testing, chest radiography, and electrocardiography help

diagnose infections, metabolic disturbances, toxins, and systemic conditions.

Neuroimaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging

should be performed when the initial evaluation does not identify a cause or

raises concern for intracranial pathology. Lumbar puncture and electroenceph-

alography are also important diagnostic tests in the evaluation of AMS. Patients

at increased risk of AMS benefit from preventive measures. The underlying

etiology determines the definitive treatment. When intervention is needed to

control patient behaviors that threaten themselves or others, nonpharmacologic interventions are preferred to medica-

tions. Physical restraints should rarely be used and only for the shortest time possible. Medications should be used only

when nonpharmacologic treatments are ineective. (Am Fam Physician. 2021; 104(5):461-470. Copyright © 2021 American

Academy of Family Physicians.)

Illustration by Todd Buck

Downloaded from the American Family Physician website at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright © 2021 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncom-

mercial use of one individual user of the website. All other rights reserved. Contact copyrights@aafp.org for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Downloaded from the American Family Physician website at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright © 2021 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncom-

mercial use of one individual user of the website. All other rights reserved. Contact copyrights@aafp.org for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

462 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 104, Number 5

◆

November 2021

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

attention, awareness, and cognition that are not attribut-

able to a neurocognitive disorder. Evidence of a secondary

cause of AMS is oen also present.

6,9

Other features include

sleep disturbances, hallucinations, delusions, inappro-

priate behavior, and emotional instability.

11

Delirium was

reviewed in a previous American Family Physician article.

6

Evaluation

Changes in consciousness, appearance, behavior, mood,

aect, or motor activity are usually apparent by general

observation and interaction with the patient.

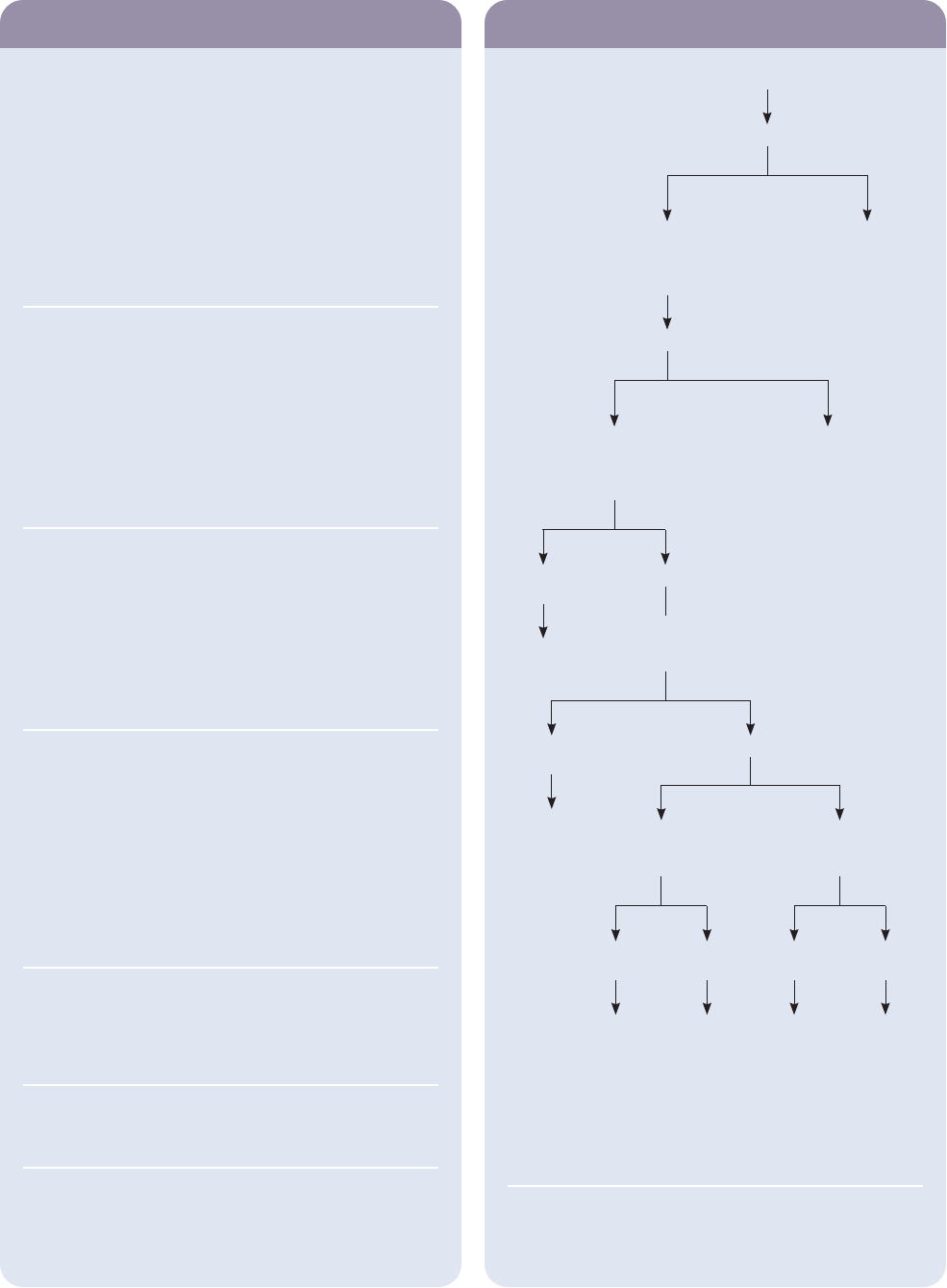

URGENT INTERVENTION

AMS can be caused by a life-threatening condition. ere-

fore, the rst step in evaluating the patient is addressing

abnormalities in the airway, breathing, and circulation

(ABCs; Figure 1).

2,3,10,12-18

Once the ABCs have been stabilized, clinicians should

evaluate for other conditions for which rapid intervention

is needed to decrease the risk of morbidity and mortality.

Abnormal vital signs may identify an obvious cause such

as hypothermia, hypoxemia, or a hypertensive emergency,

and such abnormalities should be addressed urgently.

2,3,10

A point-of-care glucose level should be obtained, and

if hypoglycemia is present, glucose should be adminis-

tered immediately unless the patient is at risk of thia-

mine deciency (e.g., alcoholism, gastric bypass surgery).

en thiamine must be administered before glucose to

avoid Wernicke encephalopathy (i.e., AMS, oculomotor

dysfunction, and ataxia due to thia-

mine deciency).

2,3,10

If concern exists for intracranial

hemorrhage (e.g., anticoagulated state,

head trauma) or ischemic stroke (e.g.,

focal abnormalities found during a

neurologic examination), neuroim-

aging should be performed immedi-

ately to determine the next steps for

care. Patients with a hemorrhage may

require urgent surgery, and those with

ischemic stroke can be triaged for

reperfusion.

2,3,10

Patients with status epilepticus

need urgent anticonvulsive therapy

and serum sodium testing. Patients

with suspected sepsis require uid

resuscitation, urgent broad-spectrum

antibiotics aer cultures are obtained,

and source control. Similarly, if

meningitis is suspected, antibiot-

ics at appropriate doses are urgently

required following neuroimaging and lumbar puncture.

If clinical suspicion is high and lumbar puncture will be

delayed, antibiotics should be given empirically. When an

opiate overdose is suspected, naloxone should be adminis-

tered immediately.

2,3,10

TABLE 1

Incidence and Prevalence of Delirium

in Older People

Setting Rate

Incidence during hospital admission

After hip fracture 28% to 61%

After surgery 15% to 53%

During hospitalization (medical inpatients) 3% to 29%

Prevalence

Intensive care unit

With mechanical ventilation 60% to 80%

Without mechanical ventilation 20% to 50%

Hospice 29%

Community (people 85 years or older) 14%

At hospital admission 10% to 31%

Long-term care facility and postacute care 1% to 60%

Adapted with permission from Kalish VB, Gillham JE, Unwin BK.

Delirium in older persons: evaluation and management [published

corrections appear in Am Fam Physician. 2015; 92(6): 430, and Am

Fam Physician. 2014; 90(12): 819]. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90(3): 152.

BEST PRACTICES IN NEUROLOGY

Recommendations from the Choosing Wisely Campaign

Recommendation

Sponsoring

organization

Do not assume a diagnosis of dementia in an older adult who

presents with an altered mental status and/or symptoms of con-

fusion without assessing for delirium or delirium superimposed

on dementia using a brief, sensitive, validated assessment tool.

American Acad-

emy of Nursing

Do not use antipsychotics as the first choice to treat behavioral

and psychological symptoms of dementia.

American Geriat-

rics Society

Do not use physical or chemical restraints, outside of emer-

gency situations, when caring for long-term care residents with

dementia who display behavioral and psychological symptoms

of distress; instead, assess for unmet needs or environmental

triggers and intervene using nonpharmacologic approaches

initially whenever possible.

American Acad-

emy of Nursing

Source: For more information on the Choosing Wisely Campaign, see https:// www.choosing

wisely.org. For supporting citations and to search Choosing Wisely recommendations relevant

to primary care, see https:// www.aafp.org/afp/recommendations/search.htm.

November 2021

◆

Volume 104, Number 5 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 463

TABLE 2

Selected Causes of Recent Changes

in Mental Status

Central nervous system insults

Demyelinating conditions

Direct brain trauma

(concussion)

Epidural hematoma

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage

Ischemic stroke

Meningoencephalitis

Neoplasm (primary or

metastatic)

Seizure (status epilepticus,

nonconvulsive status epi-

lepticus, or postictal state)

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Subdural hematoma

Commonly used medications

Antibiotics (fluoroquinolones,

cephalosporins)

Antidepressants (tertiary amine

tricyclics, monoamine oxidase

inhibitors)

Antipsychotics

Benzodiazepines

Beta blockers

Bladder antispasmodics

Dopamine agonists

General anesthetics

Opioid analgesics

Sedatives or hypnotics

Skeletal muscle relaxants

Sympathomimetics

Metabolic disturbances

Hepatic failure

Hypercalcemia

Hypermagnesemia

Hypoadrenalism/

hyperadrenalism

Hypoglycemia/

hyperglycemia

Hyponatremia/

hypernatremia

Hypophosphatemia

Hypothyroidism/

hyperthyroidism

Renal failure

Thiamine deficiency

Systemic diseases or conditions

Arrhythmia

Autoimmune conditions

Constipation

Dehydration

Heart failure

Hypercapnia

Hypertensive emergency

Hypothermia

Hypoxia

Myocardial infarction

Pain

Pancreatitis

Primary psychiatric

conditions

Sleep deprivation

Urinary retention

Systemic infections

Acute viral (influenza,

COVID-19, and others)

Intra-abdominal

Pneumonia

Sepsis

Urinary tract

Toxins

Alcohol (withdrawal or

intoxication)

Illicit substances (with-

drawal or intoxication)

Note: A single etiology may cause the altered mental status, but often

the change results from the additive eect of coexisting conditions.

The conditions in this table are also the secondary causes of delirium,

and often more than one abnormality is causing the delirium.

Information from references 2-4, 9, and 10.

FIGURE 1

Algorithm for the initial evaluation and management

of patients with recent altered mental status.

Information from references 2, 3, 10, and 12-18.

Diagnosis unclear

Neuroimaging if not

already completed;

additional testing†

Magnetic resonance

imaging of the brain if

not already completed

Consider electroen-

cephalography and

lumbar puncture

Diagnosis

unclear

Specialty

consultation

Diagnosis

unclear

Specialty

consultation

Diagnosis

identified

Treat

Diagnosis

identified

Treat

Diagnosis unclearDiagnosis

identified

Treat

Diagnosis

identified

Treat

accordingly

Complete comprehensive history

and physical examination; diag-

nostic studies as indicated per

history and physical examination†

No

Intervene according to the

diagnosis‡ (e.g., bacterial

meningitis, hypoglycemia,

intracranial bleeding,

opiate overdose, sepsis,

status epilepticus, stroke)

Yes

Address, specialty

consultation

Yes

Check vitals, glucose level, and

complete a history and physical exam-

ination; urgent testing as indicated by

history and physical examination*

Time-sensitive diagnosis identified?

No

Evaluate ABCs

Abnormalities with ABCs?

ABCs = airway, breathing, circulation.

*—Examples of urgent testing are neuroimaging to identify or rule out

intracranial hemorrhage, sodium level for acute seizure, blood cultures

for sepsis, and lumbar puncture for meningitis. See text for details.

†—See text for discussion on diagnostic testing options.

‡—See text for details on interventions.

464 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 104, Number 5

◆

November 2021

TABLE 3

Components of the Mental Status Examination for Identifying Causes of Recent-Onset Altered

Mental Status

Component Definition/content What to assess Sample questions/tests Potential diagnoses if abnormal

General observations

Appearance

and behavior

Body habitus, eye contact,

interpersonal style, style

of dress

Appearance: attention to detail, attire,

distinguishing features (e.g., scars, tattoos),

grooming, hygiene

Behavior: candid, congenial, cooperative,

defensive, engaging, guarded, hostile, irrita-

ble, open, relaxed, resistant, shy, withdrawn

Eye contact: fleeting, good, none, sporadic

NA Disheveled: depression, schizophrenia/psychotic disorder, sub-

stance use

Irritable: anxiety

Paranoid: psychotic disorder

Poor eye contact: depression, psychotic disorder

Provocative: personality disorder or trait

Mood and

aect

Mood: subjective report of

emotional state by patient

Aect: objective observa-

tion of patient’s emotional

state by physician

Body movements/making contact with oth-

ers, facial expressions (tearfulness, smiles,

frowns)

How is your mood?

Have you felt sad/discouraged lately?

Have you felt energized/out of control

lately?

Mood disorder, schizophrenia, substance use

Motor

activity

Facial expressions, move-

ments, posture

Akathisia: excessive motor activity (e.g., pac-

ing, wringing of hands, inability to sit still)

Bradykinesia: psychomotor retardation

(e.g., slowing of physical and emotional

reactions)

Catatonia: immobility with muscular rigidity

or inflexibility

NA Akathisia: anxiety, drug overdose or withdrawal, medica-

tion eect, mood disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder,

schizophrenia

Bradykinesia: depression, medication eect, schizophrenia

Catatonia: schizophrenia/psychotic disorder, severe depression

Cognitive functioning

Attention Ability to focus based on

internal or external priorities

— Count by sevens or fives

Spell a word backward

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, delirium, mood disorder,

psychotic disorder

Executive

functioning

Ordering and implementa-

tion of cognitive functions

necessary to engage in

appropriate behaviors

Testing each cognitive function involved in

completing a task

Oral Trail-Making Test: ask patient to alter-

nate numbers with letters in ascending order

(e.g., A1, B2, C3)

Delirium, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, stroke

Gnosia Ability to name objects and

their function

— Show patient a common object (e.g., pen,

watch, mobile phone) and ask if they can

identify it and describe how it is used

Stroke

Language Verbal or written

communication

Appropriateness of conversation, rate of

speech (> 100 words per minute is normal;

< 50 words per minute is abnormal), reading

and writing appropriate to education level

NA Rapid or pressured speech: mania

Slow or impoverished speech: delirium, depression, schizophrenia

Inappropriate conversation: personality disorder, schizophrenia

Limited literacy skills: depression

Memory Recall of past events Declarative: recall of recent and past events

Procedural: ability to complete learned

tasks without conscious thought

When is your birthday?

What are your parents’ names?

Where were you born?

Where were you on September 11, 2001?

Ask patient to repeat three words immedi-

ately and again in five minutes

Ask patient to sign their name while answer-

ing unrelated questions (each test must be

tailored to the individual patient)

Short-term deficit: amotivation, attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder, inattention, substance use

Long-term deficit: amnesia, dissociative disorder

Orientation Ability of patient to recog-

nize their place in time and

space

Time, space, person What year/month/day/time is it?

What city/building/floor/room are you in?

What is your name? When were you born?

Amnesia, delirium, mania, severe depression

Note: Each of these items may be suggestive of diagnoses, but none is sucient to make a diagnosis without a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

NA = not applicable.

continues

November 2021

◆

Volume 104, Number 5 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 465

IDENTIFYING THE CAUSE OF AMS

Aer addressing the need for immediate interventions, a

complete history should be obtained to identify the cause of

a patient’s AMS. A surrogate historian is oen needed.

2,3,9,10

Baseline cognitive function should be claried. e tim-

ing of the onset of mental status changes is also import-

ant because abrupt and severe changes indicate a more

serious pathology. e results of numerous observational

assessments and answers to questions asked directly to

the patient (when possible) can oen suggest a cause

1-3,10

(Table 3

1

).

Delirium is common but frequently overlooked, and

is associated with serious medical conditions; therefore,

assessment for delirium should always be considered in

patients with acute AMS, especially in those at high risk

(Table 4).

6,9,11

e Confusion Assessment Method is a widely

used, validated tool to identify delirium with a high sensi-

tivity (94% to 100%) and specicity (90% to 95%)

11

(Table 5

6

).

e 4 A’s test is also a reliable screening tool (sensitivity of

89.7% and specicity of 84.1%) and is available at https://

www.mdcalc.com/4-test-delirium-screening.

11

e ultra-

brief test requires only two questions—What is the day of

the week? and Name the months of the year backwards—and

has a sensitivity of 93% and specicity of 64%. e high

sensitivity makes it useful to rule out delirium when both

questions are answered correctly, but a positive test (i.e.,

incorrect answers) requires conrmation with a tool such as

the Confusion Assessment Method.

11,19

A thorough medication history, including new or recent

changes in prescription medications, over-the-counter

medications, herbal products, and nutritional supplements,

is essential. Consulting the patient’s pharmacy may help

with this task. Comorbid medical conditions, recent surger-

ies or procedures, and the use of alcohol and recreational

drugs can increase the risk of or cause AMS and should be

identied.

2,3,9,10

Other aspects of the history should focus on associ-

ated symptoms or events of infection, trauma, neurologic

changes, and headaches, any of which might identify a pre-

cipitating cause. A complete review of systems may uncover

additional factors (e.g., constipation, urinary retention)

contributing to AMS.

2,3,9,10

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

e neurologic examination is important to identify AMS

and determine the cause. In addition to the mental status

examination, cranial nerves, motor function, reexes, sen-

sation, and coordination should be evaluated. Focal abnor-

malities can suggest intracranial pathology such as stroke,

neoplasm, or demyelinating conditions. If a patient is exhib-

iting asterixis, it suggests metabolic encephalopathy.

1-3,10,12

TABLE 3

Components of the Mental Status Examination for Identifying Causes of Recent-Onset Altered

Mental Status

Component Definition/content What to assess Sample questions/tests Potential diagnoses if abnormal

General observations

Appearance

and behavior

Body habitus, eye contact,

interpersonal style, style

of dress

Appearance: attention to detail, attire,

distinguishing features (e.g., scars, tattoos),

grooming, hygiene

Behavior: candid, congenial, cooperative,

defensive, engaging, guarded, hostile, irrita-

ble, open, relaxed, resistant, shy, withdrawn

Eye contact: fleeting, good, none, sporadic

NA Disheveled: depression, schizophrenia/psychotic disorder, sub-

stance use

Irritable: anxiety

Paranoid: psychotic disorder

Poor eye contact: depression, psychotic disorder

Provocative: personality disorder or trait

Mood and

aect

Mood: subjective report of

emotional state by patient

Aect: objective observa-

tion of patient’s emotional

state by physician

Body movements/making contact with oth-

ers, facial expressions (tearfulness, smiles,

frowns)

How is your mood?

Have you felt sad/discouraged lately?

Have you felt energized/out of control

lately?

Mood disorder, schizophrenia, substance use

Motor

activity

Facial expressions, move-

ments, posture

Akathisia: excessive motor activity (e.g., pac-

ing, wringing of hands, inability to sit still)

Bradykinesia: psychomotor retardation

(e.g., slowing of physical and emotional

reactions)

Catatonia: immobility with muscular rigidity

or inflexibility

NA Akathisia: anxiety, drug overdose or withdrawal, medica-

tion eect, mood disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder,

schizophrenia

Bradykinesia: depression, medication eect, schizophrenia

Catatonia: schizophrenia/psychotic disorder, severe depression

Cognitive functioning

Attention Ability to focus based on

internal or external priorities

— Count by sevens or fives

Spell a word backward

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, delirium, mood disorder,

psychotic disorder

Executive

functioning

Ordering and implementa-

tion of cognitive functions

necessary to engage in

appropriate behaviors

Testing each cognitive function involved in

completing a task

Oral Trail-Making Test: ask patient to alter-

nate numbers with letters in ascending order

(e.g., A1, B2, C3)

Delirium, mood disorder, psychotic disorder, stroke

Gnosia Ability to name objects and

their function

— Show patient a common object (e.g., pen,

watch, mobile phone) and ask if they can

identify it and describe how it is used

Stroke

Language Verbal or written

communication

Appropriateness of conversation, rate of

speech (> 100 words per minute is normal;

< 50 words per minute is abnormal), reading

and writing appropriate to education level

NA Rapid or pressured speech: mania

Slow or impoverished speech: delirium, depression, schizophrenia

Inappropriate conversation: personality disorder, schizophrenia

Limited literacy skills: depression

Memory Recall of past events Declarative: recall of recent and past events

Procedural: ability to complete learned

tasks without conscious thought

When is your birthday?

What are your parents’ names?

Where were you born?

Where were you on September 11, 2001?

Ask patient to repeat three words immedi-

ately and again in five minutes

Ask patient to sign their name while answer-

ing unrelated questions (each test must be

tailored to the individual patient)

Short-term deficit: amotivation, attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder, inattention, substance use

Long-term deficit: amnesia, dissociative disorder

Orientation Ability of patient to recog-

nize their place in time and

space

Time, space, person What year/month/day/time is it?

What city/building/floor/room are you in?

What is your name? When were you born?

Amnesia, delirium, mania, severe depression

Note: Each of these items may be suggestive of diagnoses, but none is sucient to make a diagnosis without a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

NA = not applicable.

continues

466 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 104, Number 5

◆

November 2021

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

TABLE 3 (continued)

Components of the Mental Status Examination for Identifying Causes of Recent-Onset Altered

Mental Status

Component Definition/content What to assess Sample questions/tests Potential diagnoses if abnormal

Cognitive functioning (continued)

Praxis Ability to carry out inten-

tional motor acts

Apraxia: inability to carry out motor acts;

deficits may exist in motor or sensory sys-

tems, comprehension, or cooperation

Could you show me how to use this

hairbrush/hammer/pencil?

Delirium, intoxication, stroke

Prosody Ability to recognize the

emotional aspects of

language

— Repeat “Why are you here?” with multiple

inflections (e.g., happy, surprised, excited,

angry, sad) and ask patient to identify the

emotion

Ask the patient to say the same sentence

with each of the above emotional inflections

Mood disorder, schizophrenia

Thought

content

What the patient is thinking Delusions, hallucinations, homicidality,

obsessions, phobias, suicidality

Do you have thoughts or images in your

head that you cannot get out?

Do you have any irrational or excessive fears?

Do you think people are trying to hurt you in

some way?

Are people talking behind your back?

Do you think people are stealing from you?

Do you feel life is not worth living?

Do you see things that upset you?

Do you ever see/hear/smell/taste/feel things

that are not really there?

Have you ever heard or seen something

other people have not?

Have you ever thought about hurting others

or getting even with someone who wronged

you?

Have you ever thought about hurting your-

self? If so, how would you do it?

Have you ever thought the world would be

better o without you?

Delusions: fixed delusions, mania, psychotic disorder/

psychotic depression

Hallucinations: delirium, mania, schizophrenia, severe

depression, substance use

Homicidality: mood disorder, personality disorder, psychotic

disorder

Obsessions: obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic

stress disorder, psychotic disorder

Phobias: anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder

Suicidality: depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, sub-

stance use

Thought

processes

Organization of thoughts in

a goal-oriented pattern

Circumferential: patient goes through mul-

tiple related thoughts before arriving at the

answer to a question

Disorganized thoughts: patient moves from

one topic to another without organization

or coherence

Tangential: patient listens to question and

begins discussing related thoughts, but

never arrives at the answer

Generally apparent throughout the

encounter

Anxiety, delirium, depression, schizophrenia, substance use

Visuospatial

proficiency

Ability to perceive and

manipulate objects and

shapes in space

— Ask patient to copy intersecting pentagons

or a three-dimensional cube on paper

Draw a triangle and ask patient to draw the

same shape upside down

Delirium, stroke

Note: Each of these items may be suggestive of diagnoses, but none is sucient to make a diagnosis without a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

NA = not applicable.

Adapted with permission from Norris D, Clark MS, Shipley S. The mental status examination. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 94(8): 636.

November 2021

◆

Volume 104, Number 5 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 467

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

Attention to eye and vision abnormalities can also pro-

vide important diagnostic clues. Visual eld defects can

indicate a stroke. Pupillary abnormalities may be present

with substance abuse, stroke, or pending cerebral hernia-

tion. e ability to perform extraocular movements may

dierentiate a suspected comatose patient from one with

a locked-in syndrome. Ophthalmoplegia is an important

nding of Wernicke encephalopathy, and nystagmus can

identify drug intoxication or stroke. Papilledema suggests

increased intracranial pressure.

2,3,10

Examination of the head, ears, nose, and throat should

focus on signs of trauma and infection. When examin-

ing the neck, thyroid abnormalities and meningismus are

important ndings that suggest thyroid disorders and ner-

vous system infections, respectively. Examination of the

heart, lungs, and abdomen can indicate important sys-

temic causes of AMS, such as heart failure, pneumonia, and

decompensated hepatic disease.

2,3,10

Examination of the skin can show signs of chronic sys-

temic disease (e.g., jaundice), systemic infection (e.g., pete-

chiae), or local infection with cellulitis or abscess, or locate

medication patches. A musculoskeletal examination may

identify inamed joints indicating infection or an autoim-

mune condition.

2,3,10

A genitourinary and rectal examination can identify

infection. e rectal examination can show gastrointes-

tinal bleeding or neurologic compromise when tone is

reduced.

2,3,10

TESTING

e history and physical examination guide diagnostic test-

ing; however, the following initial tests can be considered

for all patients with AMS when the diagnosis is not clear:

complete blood count, electrolytes, liver function tests,

serum ammonia, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, phospho-

rus, magnesium, blood gas analysis, thyroid testing, blood

culture, urinalysis, viral antigen or polymerase chain reac-

tion tests when community prevalence is high, toxicology

screening, chest radiography, and electrocardiography.

2,3,10

Considering that the above tests are noninvasive and rel-

atively inexpensive, they should be used liberally, especially

when the etiology is not clear from the history and physi-

cal examination. Additional tests to consider when initial

evaluation is not diagnostic are adrenal function, erythro-

cyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, extended tox-

icology screening, and serologic testing for autoimmune

disorders.

2,3,10

NEUROIMAGING

Unless the etiology is clear and the risk of intracranial

pathology is low, neuroimaging should be included in the

TABLE 3 (continued)

Components of the Mental Status Examination for Identifying Causes of Recent-Onset Altered

Mental Status

Component Definition/content What to assess Sample questions/tests Potential diagnoses if abnormal

Cognitive functioning (continued)

Praxis Ability to carry out inten-

tional motor acts

Apraxia: inability to carry out motor acts;

deficits may exist in motor or sensory sys-

tems, comprehension, or cooperation

Could you show me how to use this

hairbrush/hammer/pencil?

Delirium, intoxication, stroke

Prosody Ability to recognize the

emotional aspects of

language

— Repeat “Why are you here?” with multiple

inflections (e.g., happy, surprised, excited,

angry, sad) and ask patient to identify the

emotion

Ask the patient to say the same sentence

with each of the above emotional inflections

Mood disorder, schizophrenia

Thought

content

What the patient is thinking Delusions, hallucinations, homicidality,

obsessions, phobias, suicidality

Do you have thoughts or images in your

head that you cannot get out?

Do you have any irrational or excessive fears?

Do you think people are trying to hurt you in

some way?

Are people talking behind your back?

Do you think people are stealing from you?

Do you feel life is not worth living?

Do you see things that upset you?

Do you ever see/hear/smell/taste/feel things

that are not really there?

Have you ever heard or seen something

other people have not?

Have you ever thought about hurting others

or getting even with someone who wronged

you?

Have you ever thought about hurting your-

self? If so, how would you do it?

Have you ever thought the world would be

better o without you?

Delusions: fixed delusions, mania, psychotic disorder/

psychotic depression

Hallucinations: delirium, mania, schizophrenia, severe

depression, substance use

Homicidality: mood disorder, personality disorder, psychotic

disorder

Obsessions: obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic

stress disorder, psychotic disorder

Phobias: anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder

Suicidality: depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, sub-

stance use

Thought

processes

Organization of thoughts in

a goal-oriented pattern

Circumferential: patient goes through mul-

tiple related thoughts before arriving at the

answer to a question

Disorganized thoughts: patient moves from

one topic to another without organization

or coherence

Tangential: patient listens to question and

begins discussing related thoughts, but

never arrives at the answer

Generally apparent throughout the

encounter

Anxiety, delirium, depression, schizophrenia, substance use

Visuospatial

proficiency

Ability to perceive and

manipulate objects and

shapes in space

— Ask patient to copy intersecting pentagons

or a three-dimensional cube on paper

Draw a triangle and ask patient to draw the

same shape upside down

Delirium, stroke

Note: Each of these items may be suggestive of diagnoses, but none is sucient to make a diagnosis without a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

NA = not applicable.

Adapted with permission from Norris D, Clark MS, Shipley S. The mental status examination. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 94(8): 636.

468 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 104, Number 5

◆

November 2021

initial assessment of recent AMS.

12-14

Patients with trauma,

anticoagulation, hypertension, hypertensive emergency,

headache, nausea or vomiting, clinical concern for infec-

tion, new-onset seizure, neurologic ndings on examina-

tion, history of cancer, older age, and a known intracranial

process all require imaging. Neuroimaging should be per-

formed in patients who did not previously receive imaging

and in whom initial therapy has failed. In patients with

new-onset delirium, imaging should be considered if there

is no other obvious precipitating cause.

13

Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head is

the initial study for most patients. Noncontrast CT is widely

available, can be completed quickly, identies most pathol-

ogy requiring urgent intervention, and is better tolerated by

patients than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If MRI

is available and tolerated by the patient, it can also be the

initial imaging study and is preferred to CT if the progres-

sion of an inammatory process (e.g., multiple sclerosis)

is suspected. Contrast is helpful when infection, tumor,

inammatory pathology, or vascular abnormalities are

suspected.

13-15

MRI should be considered when CT was the initial study

but was not diagnostic; it can detect pathology not evident

on CT such as acute, minor, or posterior circulation isch-

emia, encephalitis, subtle subarachnoid hemorrhages, and

inammatory conditions. MRI may also be indicated to

better dene pathology found on CT.

13-15

LUMBAR PUNCTURE

Lumbar puncture can help identify several causes of AMS,

including meningitis, encephalitis, subarachnoid hem-

orrhage, autoimmune conditions, and metastases to the

subarachnoid space. When there is clinical suspicion for

meningitis, a lumbar puncture is mandatory. Standard

testing of cerebrospinal uid includes a cell count with

dierential, protein, glucose, and culture. Obtaining addi-

tional uid for freezing is prudent because other testing may

be needed.

2,3,20

For patients with immunosuppression, the threshold for

lumbar puncture should be low, and testing for infectious

agents will need to be broadened beyond standard testing.

Consulting an infectious disease specialist should be con-

sidered for these patients.

2,3

Patients with AMS have an increased risk of intracranial

pathology that could result in cerebral herniation from a

lumbar puncture. erefore, neuroimaging should be done

before performing a lumbar puncture.

2,3,21

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

Electroencephalography is an important study to rule out

nonconvulsive seizures, which may occur in 8% to 30% of

patients with AMS without an obvious cause.

16

It can also

help diagnose metabolic encephalopathy and infectious

encephalitis.

17,18

A normal electroencephalogram may help

exclude a suspected seizure disorder and support a primary

psychiatric cause of AMS.

PATIENTS WITH UNDERLYING DEMENTIA

Patients with dementia have an increased risk of AMS.

6,9,11

Clinicians are oen challenged to determine if decits are

chronic or new, and substantial eorts should be made to

identify the patient’s baseline status. Clinicians should bal-

ance the risk of unnecessary testing and intervention for

TABLE 5

Confusion Assessment Method

for the Diagnosis of Delirium

(1) Acute onset and fluctuating course

Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from

the patient’s baseline? Did this behavior fluctuate during the

past day (that is, did it tend to come and go or increase and

decrease in severity)?

(2) Inattention

Does the patient have diculty focusing attention; for exam-

ple, being easily distracted or having diculty keeping track

of what was being said?

(3) Disorganized thinking

Is the patient’s speech disorganized or incoherent; for example,

rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of

ideas, or unpredictable switching from subject to subject?

(4) Altered level of consciousness

Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of conscious-

ness: alert (normal); vigilant (hyperalert); lethargic (drowsy,

easily aroused); stupor (dicult to arouse); coma (unarousable)?

Note: The diagnosis of delirium requires a present/abnormal rating

for criteria 1 and 2, and either 3 or 4.

Adapted with permission from Kalish VB, Gillham JE, Unwin BK.

Delirium in older persons: evaluation and management [published

corrections appear in Am Fam Physician. 2015; 92(6): 430, and Am

Fam Physician. 2014; 90(12): 819]. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90(3): 155.

TABLE 4

Common Risk Factors for Altered Mental

Status or Delirium

Age older than 65 years

Anesthesia

Baseline cognitive impairment

Baseline poor functional status

Change in environment

Constipation and/or urinary

retention

Dehydration

Depression

History of alcohol misuse

History of delirium

Intensive care unit stay

Malnutrition

Medical illnesses

(e.g., heart, lung, liver,

kidney)

Polypharmacy

Sleep deprivation

Social isolation

Surgery

Tethers (e.g., urinary

catheter, intravenous

tubing)

Visual or hearing

impairment

Information from references 6, 9, and 11.

November 2021

◆

Volume 104, Number 5 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 469

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

chronic situations the clinician may be unaware of vs. miss-

ing a new treatable condition causing AMS. Advance direc-

tives and input from the family can help guide evaluation

and treatment decisions.

A common pitfall for patients with dementia who are in a

care facility is inappropriately attributing AMS to a urinary

tract infection. Many patients who are institutionalized

have asymptomatic bacteriuria, and treatment is not indi-

cated unless a urinary infection with symptoms is present.

22

Management should focus on identifying other causes for

the patient’s AMS.

Prevention

When patients are at risk of AMS, particularly

for delirium, nonpharmacologic preventive mea-

sures can decrease incidence, especially in those

who are hospitalized.

6,9,11

e use of multiple mea-

sures through a multidisciplinary team approach

is most eective. ere is no convincing evidence

to support the use of medications to prevent AMS

or delirium.

6,9,11

Treatment

Denitive therapy for AMS is treatment of the

underlying causes or the removal of precipitat-

ing agents. However, when patients’ behaviors

threaten themselves or others before a reversible

cause can be identied or fully treated, interven-

tion is needed to avoid harm. In these situations,

nonpharmacologic interventions are the treat-

ment of choice.

2,3,6,10,11

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENTS

Reassurance and use of de-escalation techniques by sta,

family, or friends can be eective. Reducing articial light-

ing and other environmental stimuli such as monitoring

alarms can also help calm patients. A family member or

assigned sta can stay at the patient’s bedside to ensure

that patients do not harm themselves. Additional mea-

sures include those used for AMS or delirium prevention

(Table 6

6,9,11

).

Physical restraints are not considered standard inter-

ventions and should rarely be used, and then only as a last

resort and for the shortest time possible.

2,6,9-11

SORT: KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Clinical recommendation

Evidence

rating Comments

Delirium is common but frequently overlooked, and it is associated with serious medical

conditions; therefore, screening should always be considered in patients with acute AMS,

especially in those at high risk.

6,9,11

C Systematic review, nar-

rative review, and expert

consensus

Unless the etiology is clear and the risk of intracranial pathology is low, neuroimaging

should be part of the initial assessment of recent changes in mental status. Noncontrast

computed tomography of the head is the initial study for most patients.

12-14

C Expert consensus

Electroencephalography is an important study to rule out nonconvulsive seizures, which

may occur in 8% to 30% of patients with AMS without an obvious cause.

16

C Evidence-based review

When patients are at risk of AMS or delirium, nonpharmacologic preventive measures

decrease incidence, especially in those who are hospitalized. The use of multiple measures

through a multidisciplinary team approach is most eective.

6,9,11

B Systematic review, narra-

tive reviews, and expert

consensus

Medication to manage behaviors associated with AMS should be used only when nonphar-

macologic measures are ineective, and then only when it is essential to control behavior.

Studies evaluating the eectiveness of medications used for their sedative eects yield

conflicting results, and these medications may cause harm due to adverse eects.

11,23,24

C Systematic reviews,

cohort study, and expert

consensus

AMS = altered mental status.

A = consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B = inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C = consensus, disease-oriented

evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series. For information about the SORT evidence rating system, go to https:// www.aafp.org/afpsort.

TABLE 6

Measures to Prevent Delirium

Adequate hydration

Adequate nutrition

Adequate oxygenation

Avoid constipation

Avoid tethering (intravenous

lines, monitors, Foley catheter)

Cognitively stimulating activities

Early mobilization

Ensure patient has assistive

devices (eyeglasses, hearing

aids, mobility devices)

Geriatric specialty consultation

Infection prevention

Limit psychoactive medications

Pain management

Presence of family and caretakers

Orientation (accurate calendars

and clocks, and appropriate

lighting; reorientation by sta and

family)

Sleep enhancement measures

(avoid nighttime disturbances, use

appropriate lighting, reduce noise

at night)

Information from references 6, 9, and 11.

470 American Family Physician www.aafp.org/afp Volume 104, Number 5

◆

November 2021

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

MEDICATION

Medication to manage behaviors associated with AMS

should be used only when nonpharmacologic measures are

not eective, and then only when it is essential to control

behavior. Studies evaluating the eectiveness of medications

used for their sedative eects yield conicting results and

may cause harm due to adverse eects.

11,23,24

Antipsychotics

have historically been used o-label to treat delirium; how-

ever, a recent systematic review does not support the use of

these agents in hospitalized adults with delirium.

24

Anti-

psychotics also carry a U.S. Food and Drug Administration

boxed warning about an increased risk of death when used

in older adults with dementia-related psychosis.

Benzodiazepines should generally be avoided unless

they are being used to treat alcohol withdrawal or seizures

because they may worsen delirium. For any agent, the low-

est eective dose for the minimum time necessary should

be used. Medications used when nonpharmacologic modal-

ities fail are listed in eTable A.

Data Sources: PubMed (including use of the Clinical Queries

feature), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential

Evidence Plus, and UpToDate were searched using the key terms

altered mental status and encephalopathy. Also searched were

specific etiologies of altered mental status. Search dates: Janu-

ary 19 to February 22, 2021, and August 20, 2021.

The Authors

BRIAN VEAUTHIER, MD, is the program director of the Univer-

sity of Wyoming Family Medicine Residency Program, Casper.

JAIME R. HORNECKER, PharmD, BCPS, BCACP, CDCES,

DPLA, is a clinical professor at the University of Wyoming

School of Pharmacy and the Family Medicine Residency

Program.

TABITHA THRASHER, DO, is the program director of the

University of Wyoming Geriatric Fellowship and a clinical

assistant faculty member at the University of Wyoming Family

Medicine Residency Program.

Address correspondence to Brian Veauthier, MD, 1522 E. A St.,

Casper, WY 82601 (email: bveauthi@ uwyo.edu). Reprints are

not available from the authors.

References

1. Norris D, Clark MS, Shipley S. The mental status examination. Am Fam

Physician. 2016; 94(8): 635-641. Accessed July 14, 2021. https:// www.

aafp.org/afp/2016/1015/p635.html

2. Smith AT, Han JH. Altered mental status in the emergency department.

Semin Neurol. 2019; 39(1): 5-19.

3. Douglas VC, Josephson SA. Altered mental status. Continuum (Minneap

Minn). 2011; 17(5 Neurologic Consultation in the Hospital): 967-983.

4. Erkkinen MG, Berkowitz AL. A clinical approach to diagnosing enceph-

alopathy. Am J Med. 2019; 132(10): 1142-1147.

5. Kanich W, Brady WJ, Hu JS, et al. Altered mental status: evaluation and

etiology in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002; 20(7): 613-617.

6. Kalish VB, Gillham JE, Unwin BK. Delirium in older persons: evaluation

and management [published corrections appear in Am Fam Physician.

2015; 92(6): 430, and Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90(12): 819]. Am Fam Phy-

sician. 2014; 90(3): 150-158. Accessed July 14, 2021. https:// www.aafp.

org/afp/2014/0801/p150.html

7. Witlox J, Eurelings LSM, de Jonghe JFM, et al. Delirium in elderly

patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and

dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010; 304(4): 443-451.

8. Kakuma R, du Fort GG, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency

department patients discharged home: eect on survival. J Am Geriatr

Soc. 2003; 51(4): 443-450.

9. Mattison MLP. Delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173(7): ITC49-ITC64.

10. Wilber ST, Ondrejka JE. Altered mental status and delirium. Emerg Med

Clin North Am. 2016; 34(3): 649-665.

11. Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, et al. Delirium in older persons: advances

in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017; 318(12): 1161-1174.

12. Lowenstein DH, Martin JB, Hauser SL. Chapter 415: Approach to the

patient with neurologic disease. In: Jameson JL, Kasper DL, Fauci AS,

et al., eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. McGraw-Hill;

2018.

13. Luttrull MD, Boulter DJ, Kirsch CFE, et al.; Expert Panel on Neurologi-

cal Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria acute mental status change,

delirium, and new onset psychosis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019; 16(5S):

S26 -S 37.

14. Salmela MB, Mortazavi S, Jagadeesan BD, et al.; Expert Panel on Neu-

rologic Imaging. ACR Appropriateness Criteria cerebrovascular disease.

J Am Coll Radiol. 2017; 14(5S): S34-S61.

15. Lee RK, Burns J, Ajam AA, et al.; Expert Panel on Neurological Imaging.

ACR Appropriateness Criteria seizures and epilepsy. J Am Coll Radiol.

2020; 17(5S): S293-S304.

16. Zehtabchi S, Abdel Baki SG, Malhotra S, et al. Nonconvulsive seizures

in patients presenting with altered mental status: an evidence-based

review. Epilepsy Behav. 2011; 22(2): 139-143.

17. Hemphill J III, Smith S, Josephson S, et al. Severe acute encephalop-

athies and critical weakness. In: Jameson JL, Kasper DL, Fauci AS, et

al., eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e. McGraw-Hill;

2018.

18. Young GB. Metabolic and inflammatory cerebral diseases: electrophys-

iological aspects. Can J Neurol Sci. 1998; 25(1): S16-S20.

19. Fick DM, Inouye SK, Guess J, et al. Preliminary development of an

ultrabrief two-item bedside test for delirium. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(10):

645-650.

20. Shahan B, Choi EY, Nieves G. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis [published

correction appears in Am Fam Physician. 2021; 103(12): 713]. Am Fam

Physician. 2021; 103(7): 422-428. Accessed May 29, 2021. https:// www.

aafp.org/afp/2021/0401/p422.html

21. Hasbun R, Abrahams J, Jekel J, et al. Computed tomography of the

head before lumbar puncture in adults with suspected meningitis.

N Engl J Med. 2001; 345(24): 1727-1733.

22. Stone ND, Ashraf MS, Calder J, et al.; Society for Healthcare Epidemi-

ology Long-Term Care Special Interest Group. Surveillance definitions

of infections in long-term care facilities: revisiting the McGeer criteria.

Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012; 33(10): 965-977.

23. Herzig SJ, LaSalvia MT, Naidus E, et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of

aspiration pneumonia in individuals hospitalized for nonpsychiatric

conditions: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017; 65(12): 2580-2586.

24. Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, et al. Antipsychotics for treating delirium

in hospitalized adults: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 171(7):

485-495.

November 2021

◆

Volume 104, Number 5 www.aafp.org/afp American Family Physician 470A

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS

eTABLE A

Medications Used in the Management of Agitation or Delirium When Nonpharmacologic

Interventions Fail

Drug Dose* and route

Maximum

daily dosage Onset Treatment considerations

Antipsychotics

Droperidol 2.5 to 10 mg IV 20 mg 3 to 10 minutes FDA boxed warning: increased mortality

in older patients with dementia-related

psychosis

Adverse eects: extrapyramidal symptoms,

QTc prolongation, increased risk of falls,

aspiration

5 to 10 mg IM 20 mg 3 to 10 minutes

Haloperidol 0.5 to 1 mg orally every

four to six hours

30 mg 15 to 30 minutes

0.5 to 1 mg IM/IV every

30 to 60 minutes

30 mg 5 to 20 minutes

Olanzapine (Zyprexa) 5 to 10 mg IM 30 mg 15 minutes

2.5 to 5 mg orally 20 mg 30 to 60 minutes

Quetiapine (Seroquel) 12.5 to 25 mg orally 150 mg 15 to 45 minutes

Ziprasidone (Geodon) 5 to 10 mg IM 40 mg 15 minutes

Benzodiazepines

Lorazepam (Ativan) 0.5 to 2 mg IM/IV/orally 10 mg 3 to 5 minutes May worsen delirium

Generally reserved for alcohol withdrawal

and seizures

Midazolam 2 to 5 mg IM/IV 20 mg 1 to 10 minutes

Ketamine 0.5 to 1 mg per kg IV 200 mg 0.5 minutes Use caution in patients with cardio-

vascular disease; may increase blood

pressure and heart rate

4 to 5 mg per kg IM 500 mg 3 to 4 minutes

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IM = intramuscularly; IV = intravenously.

*—Smaller initial doses repeated as needed are preferred over larger initial doses or dose escalation, especially in older adults.

Information from:

Douglas VC, Josephson SA. Altered mental status. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2011; 17(5 Neurologic Consultation in the Hospital): 967-983.

Kalish VB, Gillham JE, Unwin BK. Delirium in older persons: evaluation and management [published corrections appear in Am Fam Physician.

2015; 92(6): 430, and Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90(12): 819]. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 90(3): 150-158. Accessed July 14, 2021. https:// www.aafp.org/

afp/2014/0801/p150.html

Lexicomp Online, Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs Online. UpToDate, Inc.; 2021. Accessed August 23, 2021. https:// online.lexi.com

Linder LM, Ross CA, Weant KA. Ketamine for the acute management of excited delirium and agitation in the prehospital setting. Pharmacotherapy.

2018; 38(1): 139-151.

Mattison MLP. Delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2020; 173(7): ITC49-ITC64.

Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, et al. Delirium in older persons: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017; 318(12): 1161-1174.

Smith AT, Han JH. Altered mental status in the emergency department. Semin Neurol. 2019; 39(1): 5-19.

Wilber ST, Ondrejka JE. Altered mental status and delirium. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2016; 34(3): 649-665.

BONUS DIGITAL CONTENT