STUDY

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

Editor: Eckhard Binder

Ex-Post Evaluation Unit

PE 662.603 – February 2021

EN

Implementation

of the EU

requirements

for tax

information

exchange

European

Implementation

Assessment

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

Implementation of the

EU requirements for

tax information

exchange

European implementation assessment

In February 2020, the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and

Monetary Affairs (ECON) requested to draw up an implementation report

on the implementation of the EU requirements for tax information

exchange: progress, lessons learnt and obstacles to overcome.

Sven Giegold (Greens/EFA, Germany) has been appointed rapporteur.

This European implementation assessment (EIA) has been prepared by the

Ex-Post Evaluation Unit (EVAL) within the European Parliamentary Research

Service (EPRS) to accompany the scrutiny work of the Committee on

Economic and Monetary Affairs.

AUTHORS

1. The in-house opening analysis was written by Eckhard Binder from the Ex-Post Evaluation Unit, EPRS.

2. The research paper on the implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange: progress,

lessons learnt and obstacles to overcome, was written by Patrice Muller, Nicholas Robin and James Forrester

of LE Europe Limited and Amal Larhlid, Vanessa Vazquez-Felpeto, Vasilis Douzenis and Khush Patel of

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

The research paper was written at the request of the Ex-Post Evaluation Unit of the Directorate for Impact

Assessment and European Added Value, within the Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services

(EPRS) of the Secretariat of the European Parliament.

To contact the authors, please email: EPRS-ExPostEvaluation@ep.europa.eu

ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE

Eckhard Binder, Ex-Post Evaluation Unit, EPRS.

To contact the publisher, please e-m

ail EPRS-ExPostEvaluation@ep.europa.eu

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

Manuscript completed in February 2021.

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as

background material to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole

responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official

position of the Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

Brussels © European Union, 2021.

PE 662.603

ISBN: 978-92-846-7700-9

DOI: 10.2861/433189

CAT: QA-03-21-028-EN-N

eprs@ep.europa.eu

http://www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet)

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet)

http://epthinktank.eu (blog)

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

I

Table of frequently used abbreviations and acronyms

AEOI

automatic exchange of information

AML

anti-money-laundering

APA

advance pricing agreement

ATR

advance tax ruling

BEPS

base erosion and profit shifting

BO

beneficial ownership

CbCR

country

-by-country report

CCN

common communication network

Commission

European Commission

CRS

common reporting standard

DAC

Directive on Administrative Cooperation

DF

director's fees

DG

directorate

-general

EESC

European Economic and Social Committee

EC

European Commission

ECA

European Court of Auditors

EI

income from employment

EIA

E

uropean implementation assessment

EOIR

exchange of information on request

EP

European Parliament

EPRS

European Parliamentary Research Service

EU

European Union

EUR

euro

FATCA

Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act

IP

immovable property

LIP

life insurance products

MNE

multinational enterprise

OCTs

overseas countries and territories

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PE

N

pensions

STD

Savings Tax Directive

TIN

taxpayer identification number

US

United States

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

II

Table of contents

Table of frequently used abbreviations and acronyms ________________________________ I

PART I. IN-HOUSE INTRODU CTORY AN ALYS IS______________________________________ 1

Executive summary ____________________________________________________________ 1

1. Introduction ________________________________________________________________ 3

1.1. Context of Directive 2011/16/EU ______________________________________________ 3

1.1.1. Amendments to the DAC since 2011____________________________________________ 5

1.1.2. Implementing regulations ___________________________________________________ 7

1.2. Context of the study (DAC1-4) ________________________________________________ 8

1.2.1. Commission evaluation and reports ____________________________________________ 8

1.2.2. European Parliament committees on tax issues ____________________________________ 9

1.2.3. Council of the European Union_______________________________________________ 10

1.2.4. European Court of Auditors' special report ______________________________________ 11

1.2.5. European Economic and Social Committee opinion ________________________________ 11

1.3. Scope and methodology of the study _________________________________________ 11

2. Scope of the DAC and its amendments_________________________________________14

2.1. Forms of income and capital covered by the DAC1-2 _____________________________ 14

2.2. Cross-border tax rulings and advanced pricing arrangements (DAC3) ________________ 14

2.3. Country-by-country reports (DAC4) ___________________________________________ 15

3. Transposition of the DAC1-6 _________________________________________________16

3.1. Transposition by Member States _____________________________________________ 16

3.2. Past and present infringement procedures _____________________________________ 16

4. Data analysis ______________________________________________________________18

4.1. Data availability and limitations ______________________________________________ 18

4.2. National data sources ______________________________________________________ 19

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

III

5. Effectiveness of the DAC ____________________________________________________21

5.1. Market reactions to the DAC ________________________________________________ 21

5.1.1. Income categories ________________________________________________________ 21

5.1.2. Circumventions and loopholes _______________________________________________ 22

5.2. Obstacles to the exchange of information______________________________________ 23

5.2.1. Legal obstacle s __________________________________________________________ 23

5.2.2. Practical obstacles ________________________________________________________ 23

6. External coherence of the DAC _______________________________________________25

6.1. Comparison between the DAC2/CRS and the FATCA _____________________________ 25

6.1.1. Global Forum cooperation on the AEOI _________________________________________ 26

6.1.2. Global Forum cooperation on the EOIR _________________________________________ 26

6.2. The DAC and the Savings Tax Directive ________________________________________ 28

6.3. The use of DAC information for other purposes _________________________________ 28

6.3.1. Anti-money-laundering provisions ____________________________________________ 28

6.3.2. Judicial assistance provisions ________________________________________________ 29

7. Efficiency, EU added value and relevance ______________________________________30

7.1. Efficiency ________________________________________________________________ 30

7.2. EU added value ___________________________________________________________ 31

7.3. Relevance _______________________________________________________________ 31

8. Conclusions _______________________________________________________________33

8.1. Main findings on effectiveness _______________________________________________ 33

8.2. Main findings on coherence _________________________________________________ 34

8.3. Recommendations ________________________________________________________ 34

MAIN REFERENCES ___________________________________________________________35

Part II: Implementation of EU requirements for tax information exchange: Progress, lessons

learnt and obstacles to overcome _______________________________________________39

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

IV

Table of figures

Figure 1: Number of countries to which AEOI information was sent, 2017-2019 ____________ 26

Figure 2: Global Forum EOIR – compliance ratings of EU Member States __________________ 27

Table of tables

Table 1: Directive on administrative cooperation (DAC) ________________________________ 7

Table 2: EP resolution of 26 March 2019 and actions taken by the Commission ______________ 9

Table 3: Transposition of the DAC (state of play as of January 2021) ______________________ 16

Table 4: Key findings on the EU added value of the DAC _______________________________ 31

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

1

PART I. IN-HOUSE INTRODUCTORY ANALYSIS

Executive summary

The first part of this European implementation assessment (EIA) starts with an overview of the

context of the Directive on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation (DAC), explaining the

background and history of the legislative framework as well as the subsequent amendments that

have been made to the directive since its adoption in 2011. It also provides a summary of the

research results that are presented in the annexed research paper in the second part of the EIA.

Since the academic literature on the DAC is very limited, a starting point for this EIA was the

evaluation of the directive by the European Commission in 2019. While this evaluation did not

identify major deficiencies in the implementation of the DAC, the European Commission however

recognised that there was very little evidence to prove the effectiveness and efficiency of the

directive. This EIA therefore attempts to provide additional evidence on the implementation of the

directive, with a special focus on its effectiveness and external coherence. Due to the relatively

recent entry into force of the latest two amendments (DAC5-6), this study mainly analyses the initial

directive (DAC or DAC1) and the first three amendments (DAC2-4).

The opinions of other EU institutions and bodies are referred to in separate chapters, highlighting

the needs for reforms as regards administrative cooperation that each of them has identified. In the

case of the European Parliament, its position is exemplified using the report adopted in Ma rch 2019

by the Special Committee on financial crimes, tax evasion and tax avoidance (TAX3). The Council of

the European Union adopted its conclusions with respect to the DAC in June 2020, mentioning

potential areas of improvement of the DAC and its interoperability and convergence with other EU

legislation. In a similar way, the European Economic and Social Committee adopted an own-

initiative opinion in September 2020, asking for further improvements in administrative

cooperation in the field of taxation.

National transposition of the initial directive and the first amendments proved to be quite complex

and led to a relatively high number of cases of late transposition. The first part of the EIA shows

however that most of the infringement procedures have been closed in the meantime, with only

one infringement case currently still open for the DAC4.

Both parts of the EIA provide insights into the achievement of the directive's objectives. They show

that the directive has to some extent proven its usefulness in fighting cross-border tax fraud, evasion

and avoidance, and has a deterrent effect. However, both parts of this EIA point several times to the

fact that there is limited evidence, identifying it as the main obstacle to assessing the directive's

effectiveness. This EIA complements the publicly available evidence with new qualitative and

quantitative information mainly stemming from interviews with tax administrations and a

stakeholder survey.

For the purposes of assessing the directive's effectiveness, the first part of this EIA offers a n o verview

of the different areas that are analysed in detail in the research paper annexed in the second part.

The chapter on market reactions shows how the scope of the directive has changed over time in

order to cover an increasing number of income categories and to close existing loopholes and

prevent circumvention. Another aspect that affects the directive's effectiveness are the legal and

practical obstacles hampering the exchange of tax information. The assessment of these obstacles

has served as grounds for the suggestions made in the annexed research paper on possible

improvements in this area.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

2

The assessment of the directive's external coherence has been laid out into two subchapters, the

first one offering a comparison of the different frameworks for tax information exchanges, i.e. the

DAC, the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (Global

Forum) as well as the bilateral exchanges with the United States. To illustrate how EU Member States

perform with regard to the international exchange of tax information, this subchapter also contains

their ratings within the Global Forum framework. The second subchapter presents the interaction

and convergence between the DAC and other EU legislation in the fields of anti-money-laundering

and judicial assistance.

Despite the fact that there is broad agreement among the different institutions and stakeholders on

the usefulness of administrative cooperation in the field of taxation, there is still scope for

improvement. The analysis of the directive's effectiveness and coherence in this study and the

annexed research paper has helped highlight a number of areas where such improvements could

be made through future amendments. These include increased availability of taxpayer identification

numbers, enhanced due diligence and reporting requirements, and a broader DAC coverage.

The annexed research paper analyses the implementation of the directive based on qualitative desk

research and a literature review, targeted interviews with tax authorities, and a stakeholder survey.

The analysis of quantitative data on tax information exchanges is limited to publicly available

information in the European Commission evaluation and on quantitative information collected from

some Member States. The first part of the study also contains detailed recommendations for further

improvements to the directive's effectiveness and coherence.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

3

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of Directive 2011/16/EU

The first steps towards cooperation in the exchange of tax information in the field of direct taxation

within the EU were taken in the 1970s. In 1977, the Council adopted the Directive concerning mutual

assistance by the competent authorities of the Member States in the field of direct taxation and

taxation of insurance premiums.

1

It took another 20 years before tax information exchange became

an important topic in the international tax policy discussions.

2

In 2003, the Council adopted the EU

Savings Tax Directive. Once it entered into force in 2005,

3

this directive introduced provisions on the

first mandatory exchange among EU Member States of information of interest payments to

residents of other Member States and 10 dependent and associated territories of the Member

States.

4

In addition, the Council also concluded agreements on savings taxation with five non-EU

European countries (Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino and Switzerland).

In 2011, the Council adopted the Directive on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation

(DAC1),

5

which repealed and replaced the Mutual Assistance Directive of 1977. The DAC1 entered

into force in January 2013 and laid down the rules and procedures for cooperation between EU

Member States on the exchange of foreseeably relevant information

6

between their national tax

administrations. Besides seeking to enable the Member States to better combat tax evasion, tax

fraud and avoidance linked to aggressive tax planning, the general objectives of the directive

include i) ensuring efficient administrative cooperation between the Member States to help them

overcome the negative effects of the increasing globalisation on the internal market; ii) making tax

systems fairer; and iii) safeguarding Member States' tax revenues.

7

Going beyond the requirements of the Mutual Assistance Directive of 1977, the DAC1 intr oduced

the requirement for cooperation between tax authorities through different forms of information

exchange and other forms of cooperation, such as simultaneous controls and presence of tax

officers of a given Member State in the administrative offices of another Member State. The DAC1

also introduced a new type of mandatory automatic exchange of information (AEOI) on five specific

categories of income and capital, for which information is available (income from employment,

director's fees, pensions, life insurance products and immovable property).

1

Council Directive 77/799/EEC of 19 December 1977 concerning mutual assistance by the competent authorities of the

Member States in the field of direct taxation.

2

M. Keen and J.E. Ligthart, Information Sharing and International Taxation: A Primer, International Tax and Public Finance,

13, pp. 81–110, 2006.

3

Council Directive 2003/48/EC of 3 June 2003 on taxation of savings income in the form of interest payments

4

These 10 territories were three United Kingdom-dependent territories (Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man), the five

British Caribbean territories (Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, the Turks and Caicos Islands and the British

Virgin Islands) and the two Dutch Caribbean territories (the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba).

5

Council Directive 2011/16/EU of 15 February 2011 on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation and repealing

Directive 77/799/EEC.

6

The importance of the notion of 'foreseeable relevance' in the context of tax information exchange was stressed by the

OECD already in 2010. See: OECD,

Implementing the Tax Transparency Standards: A Handbook for Assessors and

Jurisdictions, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2010. Although the term 'foreseeable relevance' has been used in the DAC

provisions since the adoption of DAC1, the European Commission used its proposal for an amendment made in July

2020 (DAC7) to give a more precise definition of the term and the necessary supporting information that a requesting

competent authority has to provide to demonstrate the foreseeable relevance of the requested information.

7

European Commission, Evaluation of the Council Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of

taxation and repealing Directive 77/799/EEC, SWD(2019) 327 final, 2019.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

4

The changes made in the field of tax information exchange between EU Member States over the

past 10 years have also been driven by the call for more transparency and fairness of the taxation

systems within the single market. Starting with the exchange of available information and

information exchange on request, the scope of the directive has evolved over the years to include a

growing number of categories of mandatory automatic exchange. The fight against tax evasion, tax

fraud and tax avoidance has been the guiding principle, reinforced by events such as the LuxLeaks

scandal

8

in 2014, which triggered the second amendment of the DAC.

Enhanced transparency and fair competition between taxation systems can have an important

economic impact on EU Member States. In 2015, up to 40 % of global profits of multinational

companies – i.e. profits made by multinational companies outside of the country where their parent

is located – were shifted to tax havens.

9

In this context, 'the governments of the (non-haven)

European Union countries appear to be the prime losers of this shifting'.

10

Another field closely linked to tax transparency is the fight against money laundering, which has

become more prominent on the political agenda in recent years. This link became visible in the

fourth amendment of the DAC, which gives tax administrations access to beneficial ownership

information as collected under the fifth Anti-money-laundering Directive.

11

The link between tax

information exchange and the fight against money laundering is also underlined in the European

Commission's Action Plan for a comprehensive Union policy on preventing money laundering and

terrorist financing, adopted in May 2020.

12

In recent years, the European Parliament has been working extensively on the issues of tax evasion,

tax fraud and tax avoidance. Building on the work done by three special committees and a

committee of inquiry, the Parliament decided in June 2020 to set up a Subcommittee on Tax Matters

(FISC). The DAC provisions deal with the exchange of direct taxation data, i.e. in a field where the EU

has only limited competence. For that reason it was the Council, after consulting with the

Parliament, that adopted the DAC1 and its successive amendments proposed by the Commission.

The roles and positions of the Council and the Parliament are described in greater detail in the

following chapters.

Finally, the developments at the level of the European Union need to be seen in a broader,

international context. Under the patronage of the OECD, the Global Forum on Transparency and

Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (the Global Forum) has been working on the

implementation of international tax transparency and information exchange standards since 2009.

8

In November 2014, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) disclosed information on a tax ruling

between Luxembourg and more than 340 multinational companies. Through the shifting of profits to Luxembourg,

the companies had been able to reduce their tax payments. For further details, please see:

https://www.icij.org/investigations/luxembourg-leaks/about-project-luxembourg-leaks/

.

9

T. Torslov, L. Wier, G. Zucman, The Missing Profits of Nations, World Economy Database, Working Paper N

o

2020/12, April

2020.

10

ibid.

11

Directive 2018/843 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive (EU) 2015/849 on

the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing, and

amending Directives 2009/138/EC and 2013/36/EU.

12

Communication from the Commission C(2020) 2800 final of 7 May 2020 on an Action Plan for a comprehensive Union

policy on preventing money laundering and terrorist financing.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

5

1.1.1. Amendments to the DAC since 2011

Since its adoption in 2011, the directive has been amended several times. As part of a tax

transparency package, the first amendment of the directive (DAC2)

13

entered into application in

January 2016 and extended the scope of the mandatory automatic exchange of information to

information on financial accounts. Contrary to the DAC1, the exchange of this information is

mandatory because Member States are already making that information available to the United

States (US) under their bilateral agreements on the Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act (FATCA)

with this country. This requirement was included in the amendment to avoid the need of invoking

the most favoured nation clause built into the DAC.

14

The DAC2 also introduced the EU framework

for the OECD Common Reporting Standard (CRS) and repealed the Savings Tax Directive

15

that had

required the automatic exchange of information on private savings income between Member States

since 2005.

The LuxLeaks scandal that broke out at the end of 2014 encouraged the European Commission to

propose a further step towards enhanced tax transparency. As a consequence, the second

amendment of the DAC (DAC3),

16

which entered into application in January 2017, introduced the

automatic exchange of information on advance cross-border rulings and advance price

arrangements.

The third amendment (DAC4),

17

which was part of an anti-tax avoidance package presented by the

European Commission in 2016, entered into application in June 2017 and introduced the automatic

exchange of information on country-by-country reports (CbCR) for multinational enterprise (MNE)

groups. This amendment sought to combat aggressive tax planning activities by MNE groups by

tackling base erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) practices.

The fourth amendment (DAC5),

18

providing access by tax authorities to beneficial ownership

information as collected under anti-money-laundering (AML) rules, entered into application in

January 2018. This provision is thought to help tax authorities to effectively monitor how financial

institutions are applying the due diligence procedures set out in the DAC1, and to combat tax

evasion and tax fraud.

The fifth amendment (DAC6),

19

which became applicable in July 2020, introduced the requirement

for the automatic exchange of information on tax planning cross-border arrangements to create an

environment of fair taxation in the internal market.

In June 2020, in response to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Council proposed to

temporarily defer by six months (plus a possible extension by another three months) cer tain time

13

Council Directive 2014/107/EU of 9 December 2014 amending Directive 2011/16/EU as regards mandatory automatic

exchange of information in the field of taxation.

14

Under this most favoured nation clause (Article 19 of DAC), Member States are bound to provide any EU partner that

requests it with the same level of information as they provide to third countries, if this is more than provided for under

EU law.

15

Council Directive 2003/48/EC of 3 June 2003 on taxation of savings income in the form of interest payments.

16

Council Directive (EU) 2015/2376 of 8 December 2015 amending Directive 2011/16/EU as regards mandatory automatic

exchange of information in the field of taxation.

17

Council Directive (EU) 2016/881 of 25 May 2016 amending Directive 2011/16/EU as regards mandatory automatic

exchange of information in the field of taxation.

18

Council Directive (EU) 2016/2258 of 6 December 2016 amending Directive 2011/16/EU as regards access to anti-money-

laundering information by tax authorities.

19

Council Directive (EU) 2018/822 of 25 May 2018 amending Directive 2011/16/EU as regards mandatory automatic

exchange of information in the field of taxation in relation to reportable cross-border arrangements.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

6

limits for the filing and exchange of information on financial accounts, (DAC2), for the disclosure

rules for intermediaries and for tax planning cross-border arrangements (both DAC6). Nevertheless,

again in June 2020, the European Parliament adopted its position to extend these deadlines by only

three months, without the option of a further extension. On 24 June 2020, the Council adopted an

amendment of the DAC,

20

granting Member States the option to extend the time limit for cross-

border arrangements by six months and by three months for the automatic exchange of information

on financial accounts, including a possible further extension by three months for both categories.

The Commission proposed the latest amendment to the DAC (DAC7) on 15 July 2020,

21

with two

goals in mind. The first involves widening the scope of the DAC to include reporting on income

earned via digital platforms. This would concern platform sellers, not the taxation of the platform

economy as such. The objective is to ensure fair taxation of income generated through online

platforms in the internal market. The second involves addressing inefficiencies in administrative

cooperation and data exploitation, by means of introducing clarity as regards joint audits and group

requests, on the one hand, and the term 'foreseeable relevance', on the other.

22

In November 2020, the European Commission published an inception impact assessment

23

for a

future amendment of the DAC (DAC8). The inception impact assessment mentions the main specific

objectives of the intervention:

to enable tax administrations to obtain information that is necessary to make sure that

taxpayers, in particular taxpayers who earn money via crypto-assets, pay their fair share,

to provide for better cooperation across tax administrations,

to keep business compliance costs to a minimum by providing a common EU reporting

standard

After a planned public consultation phase in the first quarter 2021, the Commission intends to adopt

its proposal for the DAC8 in the course of the third quarter of 2021.

Lastly, the European Commission also proposed a codification of the DAC1-DAC6 on

12 February 2020.

24

This proposal was transmitted to the Council's preparatory bodies, and the

European Economic and Social Committee issued an opinion endorsing the proposed text in its

552th plenary session on 10 June 2020.

25

However, in view of the fact that the sixth and seventh

amendments (DAC7-8) were not part of the proposed codification, work on it is currently on hold.

The following table provides an overview of the DAC and its successive amendments.

20

Council Directive (EU) 2020/876 of 24 June 2020 amending Directive 2011/16/EU to address the urgent need to defer

certain time limits for the filing and exchange of information in the field of taxation because of the COVID-19

pandemic.

21

Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation,

COM(2020) 314 final, 15.7.2020.

22

For further details on the proposal and the accompanying impact assessment, see also: Kramer E. and Eisele K., Better

cooperation against tax fraud and evasion, Briefing, European Parliamentary Research Service, Brussels,

November 2020.

23

European Commission, Inception Impact Assessment for a Proposal for a Council Directive amending Directive

2011/16/EU as regards measures to strengthen existing rules and expand the exchange of information framework in

the field of taxation to include crypto-assets and e-money, 23.11.2020.

24

Proposal for a Council Directive on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation (codification), COM(2020) 49 final,

12.2.2020.

25

See Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee, Proposal for a Council Directive on administrative

cooperation in the field of taxation (codification), adopted on 10 June 2020.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

7

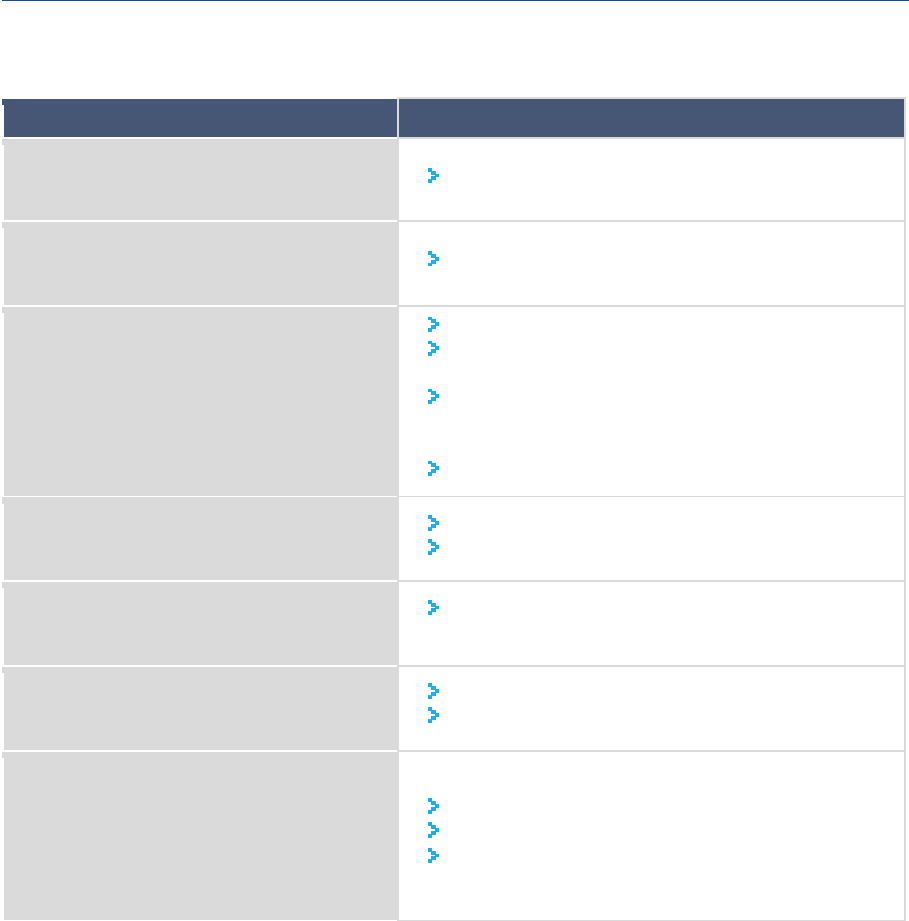

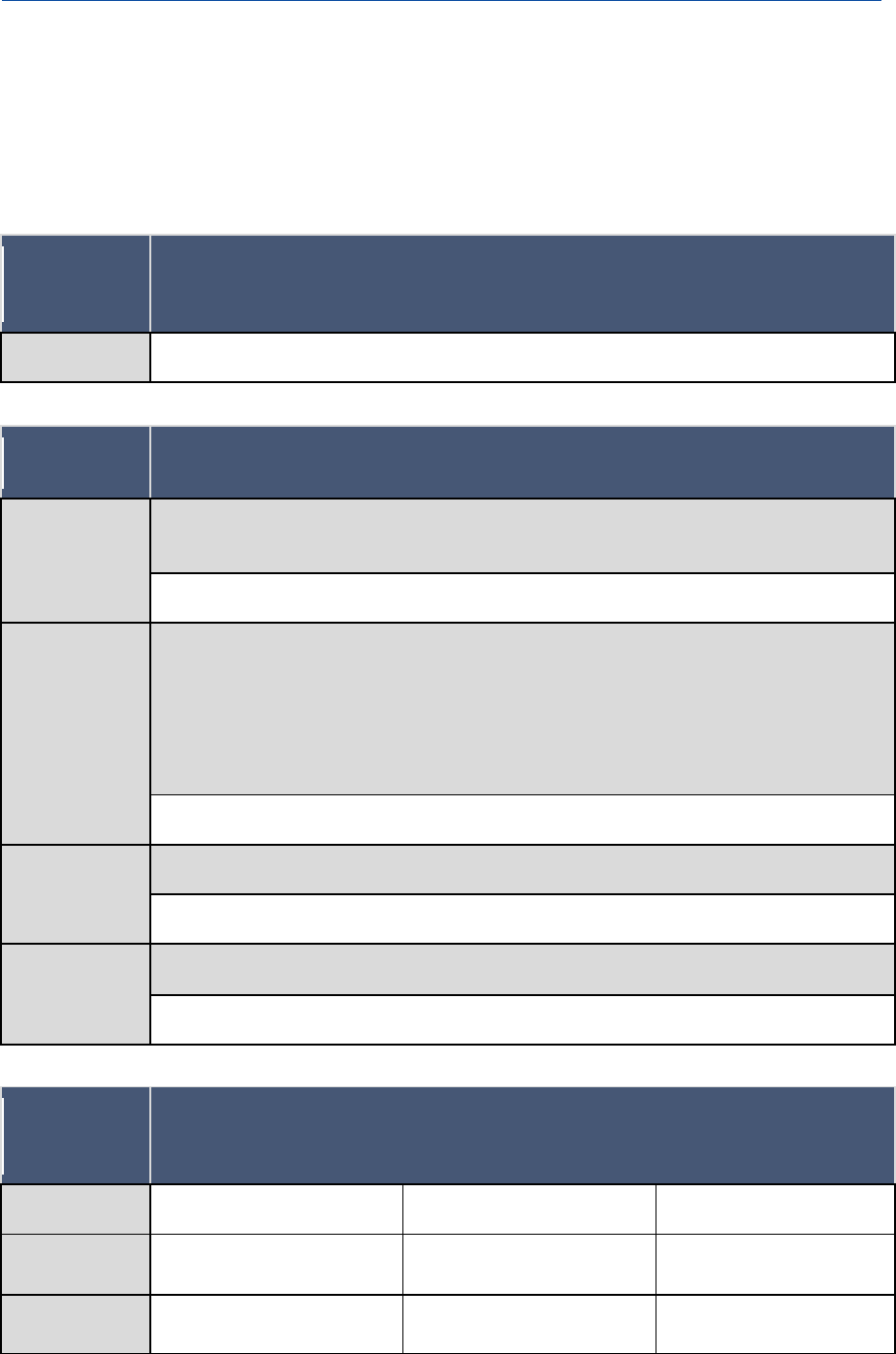

Table 1: Directive on administrative cooperation (DAC)

DAC1 DAC1 DAC2 DAC3 DAC4 DAC5 DAC6 DAC7

2011/16/EU

NON-AEOI

2011/16/EU

AEOI items

2014/107/

EU AEOI

2015/2376/

EU AEOI

2016/881/

EU AEOI

2016/2258/

EU NON-

AEOI

2018/822/

EU NON-

AEOI

Not yet

adopted

Applies

1/2013

All

exchanges

of info

except Art. 8

Applies

1/2015

1

st

exchanges

on 2014 by

30.6.2015

Art. 8

Applies

1/2016

1

st

exchanges

on 2016 by

30.9.2017

Art. 8 para 3a

Applies

1/2017

1

st

exchanges

by 30.9.2017

Art. 8a

Applies

6/2017

1

st

exchanges

on 2016 by

30.6.2018

Art. 8aa

Applies

1/2018

Art. 22, para

1a

Applies

7/2020

1

st

exchanges

by 31.8.2020

Art. 8ab and

hallmarks in

Annex 4

--

*

Exchanges

on request

*

Spontan.

exchanges

*

Presence in

adm.

offices

*

Simul tan.

controls

*

Requests

for

notification

*

Sharing

best

practices

*

Use of

standard

forms

Automatic

exchange of

information

on 5 non-

financial

categories:

*

Income from

employment

*

Director's

fees

*

Pensions

*

Life

insurance

products

*

Immovable

property

(income and

ownership)

Automatic

exchange on

financial

account

information:

*

Interests,

dividends and

other income

generated by

financial

account

*

Gross

proceeds

from sale or

redemption

*

Account

balances

Automatic

exchange of

information

(using a

central

directory as

from 1/2018)

of:

*

Advance

cross-border

rulings

*

Advance

pricing

arrange-

ments

Automatic

exchange of

information

on country-

by-country

reports on

certain

financial

information:

*

Revenues

*

Profits

*

Taxes paid

and accrued

*

Accumulated

earnings

*

Number of

employees

*

Certain

assets

Access by tax

authorities

to beneficial

ownership

information

as collected

under AML

rules

*

Mandatory

disclosure

rules for

intermediari

es

and

*

Automatic

exchange of

information

on tax

planning

cross-border

arrange-

ments

*

AEOI of

income

generated by

sellers on

digital

platforms

and

*

Explicit

inclusion of

joint audits

and group

requests

1.1.2. Implementing regulations

To ensure the uniform implementation of the DAC, the European Commission adopted several

Implementing regulations that are binding and directly applicable in all Member States. These

implementing regulations deal with the technical aspects of the implementation by the Member

States, specifying:

the standard forms for exchanges on request, spontaneous exchanges, notifications

and feedback; the computerised formats for the mandatory automatic exchange of

information; and the practical arrangements regarding the use of the Common

Communication Network (CCN),

26

the standard forms, including the linguistic arrangements, for the mandatory automatic

exchange of advance cross-border rulings and advance pricing arrangements, and the

26

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2378 of 15 December 2015 laying down detailed rules for

implementing certain provisions of Council Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of

taxation and repealing Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1156/2012.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

8

mandatory automatic exchange of information on the country-by-country report

(CbCR),

27

the form and conditions for the communication of the yearly assessment and statistical

data,

28

the standard forms, including the linguistic arrangements, for the mandatory automatic

exchange of information on reportable cross-border arrangements.

29

1.2. Context of the study (DAC1-4)

In recent years, the European Commission and other EU Institutions have presented a number of

evaluations, reports and opinions on the functioning of the DAC. This chapter provides a short

overview of the available documents.

1.2.1. Commission evaluation and reports

Recital 24 and Article 23 of the directive require the European Commission (and Member States) to

evaluate the functioning of the administrative cooperation provided for in the directive. The

European Commission presented a first evaluation of administrative cooperation in direct

taxation,

30

accompanied by a Commission staff working document,

31

in 2019. The main conclusions

of this evaluation were that, while the directive seems to be effective and efficient, there is very little

evidence to substantiate this conclusion. The evaluation also stated that the directive is relevant,

appears coherent and has EU added value. The present study therefore examines in detail the level

of effectiveness of the directive and also provides information on the – essentially external –

coherence of the directive. The other three evaluation criteria are summarised in Chapter 7.

Article 27 of the DAC requires the European Commission to report every five years on the application

of the DAC. Accordingly, the European Commission published a first report

32

and an accompanying

staff working document

33

on the application of the DAC in 2017. Due to its publication date, this

report mainly covers the application of the DAC1. The key conclusions of this report are that the

implementation of the DAC1 is of limited effectiveness. In the area of exchange of information on

request (EOIR), only 62 % of full replies were given within six months over the 2013-2016 period.

According to the report, the adoption of the DAC3 (on tax rulings and advance pricing

arrangements) led to a significant increase in the number of spontaneous exchanges in these areas

in 2016. This shows that the effectiveness of EOIR had been rather limited in previous years. In the

27

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1963 of 9 November 2016 amending Implementing Regulation (EU)

2015/2378 as regards standard forms and linguistic arrangements to be used in relation to Council Directives (EU)

2015/2376 and (EU) 2016/881.

28

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/99 of 22 January 2018 amending Implementing Regulation (EU)

2015/2378 as regards the form and conditions of communication for the yearly assessment of the effectiveness of the

automatic exchange of information and the list of statistical data to be provided by Member States for the purposes

of evaluating of Council Directive 2011/16/EU.

29

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/532 of 28 March 2019 amending Implementing Regulation (EU)

2015/2378 as regards the standard forms, including linguistic arrangements, for the mandatory automatic exchange

of information on reportable cross-border arrangements.

30

Economisti Associati srl, Evaluation of Administrative Cooperation in Direct Taxation, 2019.

31

European Commission, Evaluation of the Council Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of

taxation and repealing Directive 77/799/EEC, SWD(2019) 327 final, 2019.

32

European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the application of

Council Directive (EU) 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of direct taxation, COM(2017) 781 final,

18.12.2017.

33

European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document on the application of Council Directive (EU) no 2011/16/EU

on administrative cooperation in the field of direct taxation, SWD(2017) 462 final, 18.12.2017.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

9

field of automatic exchange of information (AEOI) under the DAC1, the main problem for the

application of the directive was the lack of resources and automated taxpayer identification

processes to make use of the information.

Finally, the European Commission published in 2018 a report on statistics within the AEOI

34

under

DAC1 to DAC3. In this report, the European Commission raised concerns about the quality of

information and the use of the data received by Member States via the AEOI. This report, which also

provided the data used in the 2019 Commission evaluation, made recommendations for enhancing

the effectiveness of the directive. First, the Commission concluded that the quality of the A EOI could

be improved through a quality review by the sending Member States and by feedback from the

receiving Member States, including feedback to the data suppliers, i.e. financial institutions. In this

context, a broader use of taxpayer identification numbers (TIN) could prove very useful. Second, the

Commission suggested that Member States should work on a common methodology to estimate

the benefits of the AEOI. Beyond possible improvements in the AEOI, Member States should also

make better use of the other formats of administrative cooperation and share best practices on the

better use of data available to them.

1.2.2. European Parliament committees on tax issues

The European Parliament has been very active in the field of tax evasion, tax fraud and tax avoidance

in recent years. Since 2015, three special committees and a committee of inquiry (in chronological

order: TAXE

35

, TAX2

36

, PANA

37

and TAX3

38

) looked at the different aspects of taxation, including the

exchange of tax information under the DAC. Most recently, the TAX3 resolution of 26 March 2019

39

highlighted a number of key areas for improvement with respect to the DAC amendments within

the scope of the present study (DAC1-DAC4). The table below shows these key areas and the action

taken and announcements made by the European Commission.

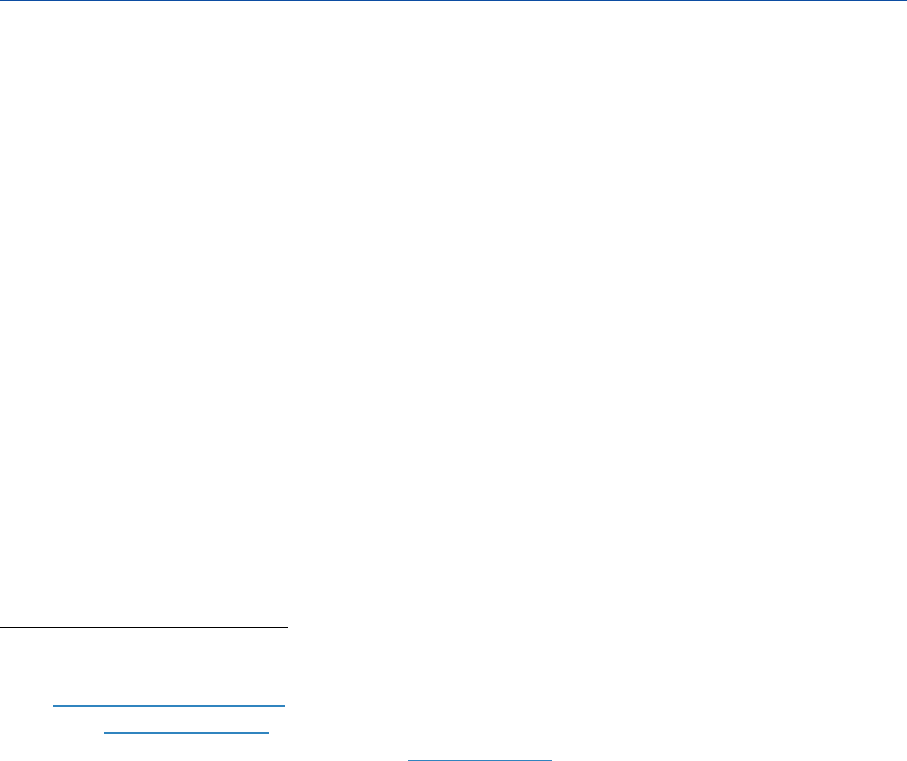

Table 2: EP resolution of 26 March 2019 and actions taken by the Commission

Resolution

Commission action/announcements

(Point 87) Calls on the Commission to assess

and present proposals to close loopholes in

DAC2, particularly by including hard assets and

cryptocurrencies in the scope of the directive,

by prescribing sanctions for non-compliance or

false reporting from financial institutions, as

well as by including more types of financial

institution and types of accounts that are not

being reported at the moment, such as pension

funds;

In 2019, the Commission published a Study on the

Evaluation of the Cooperation in Direct Taxation and a

staff working document

with the results of the

evaluation of Council Directive 2011/16/EU on

administrative cooperation in the field of taxation and

repealing Directive 77/799/EEC.

In the

Action Plan for fair and simple taxation

supporting the Recovery Package, published in

July 2020, the European Commission announced the

extension of automatic exchange of information to

34

European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on overview and

assessment of the statistics and information on the automatic exchanges in the field of direct taxation, COM(2018)

844 final, 17.12.2018.

35

Special Committee on tax rulings and other measures similar in nature or effect (TAXE) - From 12 February 2015 to

30 November 2015.

36

Special committee on tax rulings and other measures similar in nature or effect (TAXE2) - From 2 December 2015 to

2 August 2016.

37

Committee of Inquiry to investigate alleged contraventions and maladministration in the application of Union law in

relation to money laundering, tax avoidance (PANA) - From 8 June 2016 to 8 December 2017.

38

Special committee on financial crimes, tax evasion and tax avoidance (TAX3) - From 1 March 2018 to 1 March 2019.

39

European Parliament, Resolution on financial crimes, tax evasion and tax avoidance, P8_TA(2019)0240, 26 March 2019.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

10

Resolution

Commission action/announcements

crypto-assets / e-money (Action 10). A proposal is

planned for the third quarter of 2021.

(Point 88) Reiterates its call for a broader scope

in relation to the exchange of tax rulings and

broader access by the Commission, and for

greater harmonisation of the tax ruling practices

of different national tax authorities;

According to the Commission, the findings of the 2019

evaluation will be followed up by the Member States in

the Working Group on Administrative Cooperation in

the field of Direct Taxation (ACDT), with the aim of

improving the functioning of the automatic exchange

under the DAC. This will include advance cross-border

tax rulings and advance pricing arrangements as well

as, if appropriate, considera

tions for possible future

initiatives to further amend the DAC.

(Point 89) Calls on the Commission to swiftly

release its first assessment of DAC3 in this regard,

looking in particular at the number of rulings

exchanged and the number of occasions on

which national tax administrations accessed

information held by another Member State; asks

that the assessment also consider the impact of

disclosing key information related to tax rulings

(the number of rulings, the names of

beneficiaries, the effective tax rate deriving from

each ruling); invites the Member States to publish

domestic tax rulings;

The 2019 Commission evaluation contains information

that points to an increase in the number of tax rulings

recorded in the central directory. The Commission has

not proposed/promised to take any

further specific

actions.

(Point 91) Reiterates, furthermore, its call to

ensure simultaneous tax audits of persons of

common or complementary interests (including

parent companies and their subsidiaries), and its

call to further enhance tax cooperation between

Member States through an obligation to answer

group requests on tax matters; points out that the

right to remain silent in dealings with tax

authorities does not apply to a purely

administrative investigation and that

cooperation is mandatory;

In its proposal for the DAC7, the Commission tries to

clarify the provisions of the DAC with respect to joint

audits, which so far have been conducted on the basis

of the combined provisions on the presence of foreign

officials in the territory of other Member States and on

simultaneous controls.

On group requests, the proposal

clarifies that

requested authorities would have to inform the

requesting authority of the reasons

in case the

requested authority takes the view that no

administrative enquiry is necessary.

(Point 95) Calls on the Commission to swiftly

assess the implementation of DAC4 and whether

national tax administrations effectively access

country‑by‑country information held by another

Member State; asks the Commission to assess

how DAC4 relates to Action 13 of the G20/BEPS

action plan on exchange of country

‑

by

‑

country

information;

The assessment of the DAC4 implementation is part of

the 2019 Commission evaluation, which includes a

reference to the implementation of the standards of

the BEPS action 13.

1.2.3. Council of the European Union

Within the EU, legislation in the field of direct taxation is mainly a competence of the Member States.

The Council of the European Union plays therefore a central role and can adopt legislation in the

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

11

field of direct taxation by unanimity.

40

The DAC1 and its subsequent amendments were adopted as

Council directives and not under the ordinary (co-decision) procedure, which meant that the

European Parliament was only consulted before their adoption.

In its conclusions of 2 June 2020, the Council expressed the need to update the DAC and to improve

administrative cooperation in order to reduce tax fraud, tax evasion and tax avoidance, es pecia lly in

the area of income generated via digital platforms, as proposed by the European Commission in

July 2020 (DAC7).

41

At the same time, the Council also invited the European Commission to analyse

possibilities for greater interoperability between administrative cooperation in the field of direct

taxation and anti-money-laundering legislation, and enhanced convergence between the DAC and

the Regulation on combating fraud in the field of value added tax.

42

1.2.4. European Court of Auditors' special report

The European Court of Auditors is currently working on a special report on the exchange of tax

information in the EU. The publication of the report is planned for January 2021 and will assess the

effectiveness of the system set up by the Commission for the automatic exchange of tax

information. The report will look into the use of tax information received by the tax administrations

in five EU Member States (the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain and Italy).

1.2.5. European Economic and Social Committee opinion

The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) adopted an own-initiative opinion on the

European Commission's proposal for the DAC7 on 18 September 2020.

43

The opinion calls for:

the closure of gaps in the DAC concerning missing beneficial ownership information in

certain countries;

extending the scope of the DAC to also cover works of art and other high-value assets

located in free ports and customs warehouses;

public access to country-by-country reports, at least for companies receiving public aid.

As regards the fight against money laundering and tax evasion and avoidance, the EESC considers

the cooperation between the tax authorities in some EU Member States to be still unsatisfactory.

1.3. Scope and methodology of the study

For all legislation, there is a certain time lag between its adoption and the first collection of data on

its implementation. For that reason, the European Commission's Better Regulation Guidelines

recommend carrying out evaluations only once at least three years of a reasonable amount of data

has been collected.

44

In the case of the DAC, only the initial directive and the first three amendments

fulfil this condition. The main focus of this study is therefore limited to the DAC1-DAC4.

40

Based on Article 115 TEU, '...the Council shall, acting unanimously...issue directives for the approximation of such laws,

regulations or administrative provisions of the Member States as directly affect the establishment or functioning of

the internal market'.

41

Council conclusions of 2 June 2020 on the future evolution of administrative cooperation in the field of taxation in the

EU.

42

Council Regulation (EU) No 904/2010 of 7 October 2010 on administrative cooperation and combating fraud in the field

of value added tax.

43

European Economic and Social Committee, Opinion on effective and coordinated EU measures to combat tax fraud, tax

avoidance, money laundering and tax havens, ECO/510, 18 September 2020.

44

European Commission, Better Regulation Guidelines, SWD(2017) 350, 2017.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

12

Whereas the European Commission evaluation in 2019

45

covered all five evaluation criter ia

(effectiveness, efficiency, coherence, relevance and EU added value), the present study and the

annexed research paper look mainly into the effectiveness and coherence of the implementation of

the DAC. A brief summary of the other evaluation criteria, based on the Commission evaluation, can

be found in Chapter 7 of the present study.

As the directive regulates the exchange of administrative taxation data between EU Member States,

the geographical coverage of the study is to a large extent limited to the EU. In addition to the EU

Member States, the annexed research paper also provides a short analysis of the implementation of

current reporting obligations and tax information exchange flows by countries and jurisdictions

previously covered by the EU Savings Tax Directive or under similar obligations in an EU agreement

(Andorra, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino and Switzerland). With the exception

of the Cayman Islands, EU Member States' overseas countries and territories (OCTs) are not covered

by the present study. An earlier EPRS study

46

for the PANA committee has provided detailed

information on OCTs.

Finally, the research paper also looks also into the exchange of tax information at the international

level, namely in the context of the OECD/Global Forum using the Common Reporting Standard

(CRS), and between the EU and the US. Besides describing how tax information is exchanged and

what the potential shortcomings of this process are, the research paper describes the differences

between the US Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the DAC, and analyses the

reciprocity including in the intergovernmental agreements (IGA) under the FATCA.

Besides the publicly available information mentioned above, the study's main source of evidence is

the research paper in Part II, which was carried out by a consortium led by LE Europe. This res earch

paper concentrates on three broad areas:

effectiveness of the DAC. What types of income are covered/not covered by the DAC?

Have new types of income appeared after the DAC was first adopted? What are the legal

or practical obstacles to the exchange of tax information? What are the known examples

of circumvention or loopholes for the different types of information exchange under the

DAC? Definition and reporting obligations with regard to financial accounts and

beneficial ownership. This part also contains a short case study on the Cum-Ex tr ading

scandal and the description of a theoretical approach on how to use macroeconomic

data for a plausibility check of DAC2 data. A mapping of bilateral exchange flows for the

different types of exchanges was planned to be done in the context of the study, but

the lack of data rendered this impossible (see Chapter 4 for more details).

evolution of tax information exchange. Here, the intention was to assess the

evolution of the yearly tax data exchange, at least until 2018. This analysis was supposed

to build on the data already included in the Commission evaluation and the underlying

study, both published in 2019, which referred to data until 2017. As the data needed for

this analysis was not accessible to the researcher (see Chapter 4), the analys is presented

in the annexed research paper refers mainly to the Commission study and to data

collected from a few Member States.

coherence. This part of the research paper looks into the differences between the

standards used for under three different frameworks of tax information exchange (the

45

European Commission, Evaluation of the Council Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of

taxation and repealing Directive 77/799/EEC, SWD(2019) 327 final, 2019.

46

I. Ioannides and J. Tymowski, Tax evasion, money laundering and tax transparency in the EU Overseas Countries and

Territories, EPRS, European Parliament, 2017.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

13

DAC, the Global Forum's Common Reporting Standard (CRS), and the FATCA). It also

provides a short analysis of the implementation of current reporting obligations and tax

information exchange flows by countries and jurisdictions previously covered by the EU

Savings Tax Directive or under similar obligations in an EU agreement (Andorra, the

Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino and Switzerland). Finally, the study

gives an overview of the interaction between the provisions of the DAC and the EU r ules

on judicial assistance and anti-money-laundering.

The following methods were used for drawing up the study:

desk research and literature review in all three areas described above;

structured interviews with tax authorities on the effectiveness and coherence of the

DAC. These interviews were conducted with the national tax authorities of 10 EU

Member States and with officials working at the European Commission's Directorate-

General for Taxation and Customs Union. The Member States were chosen to represent

a diversity of sizes (small, medium and large) and geographical locations. The interviews

focused on the legal and practical obstacles to the exchange of tax information, on

circumventions and loopholes, and on the interoperability between the provisions of

the DAC and the EU rules on judicial assistance, money laundering and asset recovery

from a practical point of view. To measure the effect of the repeal of the Savings Tax

Directive, the interviews with national tax administrations included also questions on

the tax information exchange with countries previously covered by the Savings Tax

Directive or under similar obligations in an EU agreements;

a targeted stakeholder survey on the effectiveness and coherence of the DAC. Similar

to the interviews with the 10 Member States' tax administrations, this online survey

focused on the legal and practical obstacles to the exchange of tax information, as well

as on circumventions and loopholes. The survey also included practical questions on

the interaction between the provisions of the DAC and the EU rules on judicial

assistance, money laundering and asset recovery.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

14

2. Scope of the DAC and its amendments

This chapter provides a detailed description of the content of the DAC and its amendments, in

addition to the information laid out in Table 1 in Chapter 1.1.1.

2.1. Forms of income and capital covered by the DAC1-2

On 1 January 2015, the provisions on automatic exchange of information, which had been built into

Directive 2011/16/EU (DAC1), entered into force, thereby creating an obligation for Member States

to report with each other on the following available taxable income and capital categories of

residents in other Member States:

income from employment (EI);

director's fees (DF);

life insurance products (LIP) not covered by other EU legal instruments on exchange of

information and other similar measures;

pensions (PEN);

ownership of and income from immovable property (IP).

Since September 2017, a mandatory automatic exchange of information has been taking place as

required under the DAC2. Apart from specifying what kind of identification-related information is

needed for the exchange (account holder's name, account number, name of the reporting financial

institutions, etc.), these provisions also set the requirement for the exchange of the following

financial account information:

account balance or value;

amounts of dividends and interests;

other financial income;

capital gains.

As mentioned earlier, this broadening of the DAC's scope initiated by the European Commission in

order to better fight tax fraud, tax evasion and tax avoidance in EU Member States. At the same time,

this amendment led also to the repeal of the Savings Tax Directive,

47

under which EU Member States

had exchanged information on private savings income since its entry into application in 2005.

2.2. Cross-border tax rulings and advanced pricing arrangements

(DAC3)

In response to the LuxLeaks scandal, the DAC3 introduced provisions on the automatic exchange

on advance cross-border rulings and advance price arrangements.

48

The information exchange

covers taxpayers of all business formats (e.g. legal persons such as companies, and legal

arrangements such as trusts and foundations), but excludes rulings relating exclusively to natural

persons. The exchange takes place via a central directory database to which all Member States have

47

Council Directive 2003/48/EC of 3 June 2003 on taxation of savings income in the form of interest payments.

48

'An advance cross-border tax ruling is a confirmation or assurance that tax authorities give to taxpayers on how their tax will

be calculated in a cross-border situation before the transaction takes place. Similarly, an advance pricing arrangement

determines in advance of cross-border transactions an appropriate set of criteria between associated enterprises (i.e. group

companies) for the determination of transfer prices or determines the attribution of profit to a permanent establishment.'

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/council_directive_eu_2015_2376_en.pdf

.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

15

access. In contrast the other types of AEOI, shared via the common communication network (CCN),

the European Commission can access DAC3 information in the central directory database only for

monitoring purposes.

2.3. Country-by-country reports (DAC4)

In 2017, the DAC4 introduced the requirement for multinational enterprise (MNE) groups located in

the EU or with operations in the EU to file a country-by-country report (CbCR) if the MNE group's

total consolidated revenue is equal to or higher than €750 million. Such a CbCR has to be sent

automatically by the receiving competent authority of the Member State to any other Member

States in which one or more constituent entities (i.e. companies) of the MNE group are either

resident for tax purposes or subject to tax with respect to the business carried out through a

permanent establishment there.

The CbCR needs to contain the following information:

Aggregate information relating to the:

amount of revenue,

profit (loss) before income tax,

income tax paid,

income tax accrued,

stated capital,

accumulated earnings,

number of employees,

tangible assets other than cash or cash equivalents with regard to each

jurisdiction in which the MNE group operates.

For each constituent entity of the MNE group:

the jurisdiction of tax residence of that constituent entity,

where different from that jurisdiction of tax residence, the jurisdiction under

the laws of which that constituent entity has been established,

the nature of the main business activity or activities of that constituent entity.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

16

3. Transposition of the DAC1-6

The following sections give an overview of how the transposition and infringement procedures

under the DAC have evolved with each consecutive amendment of the DAC.

3.1. Transposition by Member States

The table below shows the timetable for the transposition of the different amendments of the DAC

into the Member States' national legislation and for their subsequent entry into application. In the

case of the DAC2, Austria had requested an extension of the deadlines by one year. To cover the

period of the late entry into application of the DAC2, Austria applied the provisions of the Savings

Tax Directive, which was repealed by the DAC2, for an additional year.

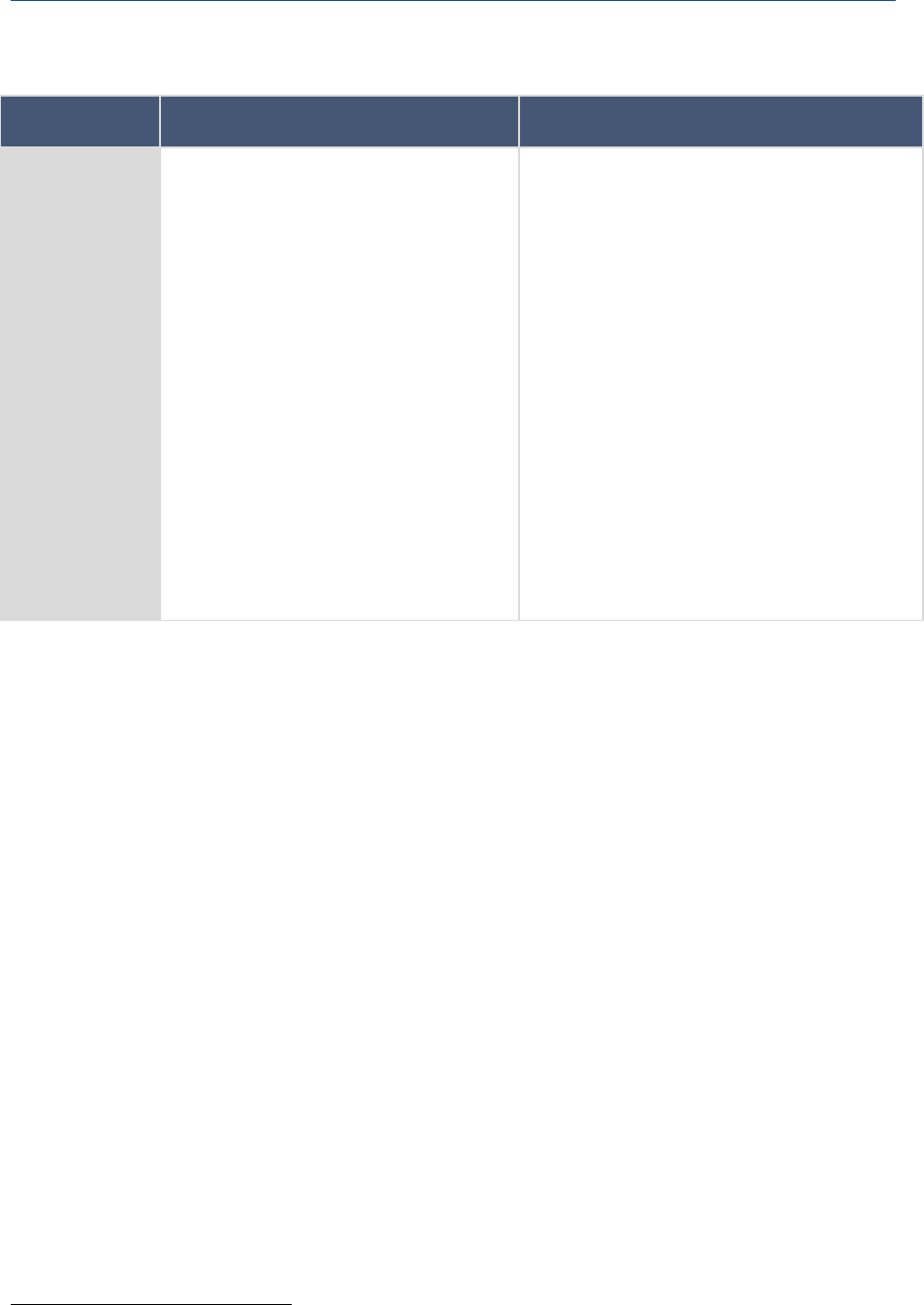

Table 3: Transposition of the DAC (state of play as of January 2021)

Directive

Transposition

deadline

Application as of

Infringements

opened

Infringements

still open

DAC1 31/12/2012 01/01/2013 14 0

DAC1 – AEOI

31/12/2012

01/01/2015

4

0

DAC2

31/12/2015

01/01/2016*

13

0

DAC3

31/12/2016

01/01/2017

9

0

DAC4

04/06/2017

05/06/2017

7

1 (ES)

DAC5

31/12/2017

01/01/2018

11

1 (IE)

DAC6

30/06/2020

01/07/2020

15

9

* 01/01/2017 for Austria.

3.2. Past and present infringement procedures

The varying number of infringement cases (see Table 3) for the respective amendments of the DAC

reflects the complexity of the amendments as well as the difficulties experienced by the Member

States in transposing the directive into their national legislation. In relation to the DAC1, almost all

opened infringement procedures were due to late transposition. Only one infringement procedure

was related to the incomplete transposition of the AEOI provisions by Estonia.

While all infringement cases concerning the transposition of the DAC2 are now closed, the relatively

high number of cases that had been opened can be explained by the complex implementation at

the Member State level. On the one hand, the amendments required the involvement of the

financial sector in the process and the development of new IT structures. On the other hand, for

some Member States, the transposition coincided with the preparation of multilateral exchanges at

OECD level and the first bilateral exchanges with the US under the FATCA.

49

Late transposition and/or notification of the European Commission were the reasons for the nine

infringement procedures with respect to the DAC3. All infringement procedures related to the

DAC1-3 are now closed.

49

Economisti Associati srl, Evaluation of Administrative Cooperation in Direct Taxation, 2019.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

17

All seven infringement procedures that had been opened for late transposition of the DAC4 are now

closed. However, the European Commission opened a new procedure against Spain in 2019. The

current rules in Spain on CbCRs by multinational companies lack a number of elements regarding

the reporting obligations.

Eleven Member States received letters of formal notice for non-compliance with the transposition

deadline for the DAC5. Most infringement cases were closed at an early stage. Ireland's case, initiated

because of the limited access afforded to the tax administration to beneficial ownership

information, is still open.

In the case of the DAC6, the European Commission sent letters of formal notice

50

to 15 Member

States in January 2020. Most of these Member States notified their response to the Commission's

letters of formal notice with a delay in the course of 2020. Whether these notifications are complete

and allow for closure of the infringement procedures is still being assessed. The infringement

procedures for France, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Romania and the United Kingdom are now

closed, while the ones for Italy, Greece, Sweden, Belgium, Estonia, Spain, Czechia, Latvia and Cyprus

were still open at the time when the present study was being drafted (mid-January 2021).

50

A letter of formal notice is the first step in an EU infringement procedure, '...giving the State concerned the opportunity to

submit its observations'. (Article 258 TFEU). More information on the different stages of an infringement procedure can

be found on the relevant European Commission website:

https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-maki ng-

process/applying-eu-law/infringement-procedure_en.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

18

4. Data analysis

The European Commission evaluation and the underlying study, both published in 2019, contain

valuable information on the tax information exchange flows emanating from the different DAC

provisions. However, the time series presented in these documents ended in 2017, which can be

explained by the publication date in 2019. The study also gave an overview of the main sending and

receiving countries of AEOI exchanges under the DAC1-3, but not under the DAC4. A description of

bilateral flows of AEOI and other forms of exchanges was also a part of the study, but only covered

the main flows, without providing a complete picture of the bilateral exchange flows in the EU.

One of the objectives of the present study was to complement the exchange flow time series with

2018 data and to give a better overview of the exchange flows, including under the provisions of

the DAC4, and of all bilateral exchange flows and Member States' replies to the questionnaires on

the yearly assessment of the DAC and its functioning. To this end, the European Parliament

requested to be granted access to DAC data by the European Commission. The chair of the European

Parliament's Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee (ECON) and the director-general of DG

TAXUD signed an arrangement for the examination of confidential documents and information as

regards the implementation of the DAC. As the request concerned confidential data submitted by

the Member States, the European Commission was bound by the Framework Agreement on

relations between the European Parliament and the European Commission

51

to ask for the Member

States' consent before providing the documents to the European Parliament. The Member States,

represented by the Council, refused to grant the European Parliament access to the data that would

have been necessary for the drawing up of the present European Implementation Assessment (EIA).

In general, countries' – not only EU Member States' – reluctance to provide data on tax information

exchanges is not new, as such information is considered confidential.

52

Due to the Member States' refusal to grant access to data for the purposes of this study, the

following subchapters and the annexed research paper relied to a large extent on publicly available

information, i.e. the relevant documents that the European Commission has published in recent

years. In addition, the above-mentioned sources – interviews with national tax administrations and

European Commission officials and a stakeholder survey – were used to collect additional

information. Finally, national parliaments also provided useful information on the implementation

of the DAC at the national level in reply to a request sent via the European Centre for Parliamentary

Research and Documentation.

53

Chapter 3.1.2 of the annexed research paper provides an overview

of these national data sources on information exchange under the DAC1-4.

4.1. Data availability and limitations

One of the main limitations of the 2019 European Commission evaluation of the DAC was that its

conclusions were 'grounded on limited and in some cases very thin evidence, if any at all'.

54

Any

51

Framework Agreement on relations between the European Parliament and the European Commission, OJ L 304,

20.11.2010, p. 47–62. In particular, Annex II, paragraph 2.1 of this agreement stipulated that '...Confidential information

from a State, an institution or an international organisation shall be forwarded only with its consent'.

52

M. Keen and J.E. Ligthart, Information Sharing and International Taxation: A Primer, International Tax and Public Finance,

13, pp. 81–110, 2006.

53

The ECPRD is a network of the European Parliament and the national parliaments of the Council of Europe countries. For

the purposes of this study, an information request was sent to the EU Member States only. For more information on

the ECPRD, see: https://ecprd.secure.europarl.europa.eu/ecprd/public/page/about

.

54

European Commission, Evaluation of the Council Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of

taxation and repealing Directive 77/799/EEC, SWD(2019) 327 final, 2019.

Implementation of the EU requirements for tax information exchange

19

conclusions drawn in the present study have to be seen in this context, especially given the above-

mentioned limitations on access to data. However, the fact that the European Commission and its

external contractor had access to the whole range of data on tax information exchanges under the

DAC allowed for a more complete picture of these exchanges. At the same time, the information

provided by the European Commission reflects the state of affairs in early 2019, i.e. the time when

the external study was finalised.

For the DAC1 AEOI, the European Commission evaluation showed a constant increase in the number

and value of exchanges from 2015 to mid-2017. The main problem with this type of exchange

seemed to be the availability of information on certain types of income and assets in a number of

Member States.

55

Member States have to send information only for those categories for which

information is already available. The lowest rate of information availability was observed for life

insurance products, for which only eight Member States could provide information in 2017.

According to the Commission's external study, enhanced coverage of income categories could be

achieved without additional information collection, simply by a better 'management and quality of

information already available'.

56

The DAC2 introduced the requirement for mandatory automatic exchange of all financial account

information, and data availability was therefore less problematic than for the DAC1. Yet, where the

necessary information was not readily available, Member States had to introduce new reporting

obligations. This process happened more or less at the same time as the introduction of multilateral

information exchanges under the Global Forum and the US FATCA.

57

As DAC2 exchanges were

launched in September 2017, this part of the European Commission evaluation covered only a

seven-month period, which made it impossible to draw any conclusions from the evolution of the

exchanges over time.

58

Data- and information availability is even worse when it comes to advance cross-border tax r ulings

(ATR) and advance pricing arrangements (APA) under the DAC3. Member States have exclusive

access to the central directory where ATRs and APAs are uploaded, which means that no information

is available on their content to other entities. Although the central directory existed already before

the adoption of the DAC3, most Member States only started using it with the implementation of the

DAC3 in 2017.

The European Commission evaluation did not look into the use of CbCRs under the DAC4;

quantitative information on this amendment is therefore very limited. In the context of the present

EIA, only one national parliament (Germany) informed the researchers about the existence of data

on CbCRs for the years 2016-2018.

59

4.2. National data sources