Pharma 2020: Challenging business models

Which path will you take?

Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences

Table of contents

Pharma 2020: The vision #

Pharma 2020: The vision

Which path will you take?*

Pharmaceuticals

*connectedthinking

Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D 1

Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D

Which path will you take?

Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences

Pharma 2020: Marketing the future

Which path will you take?

Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences

Previous publications in this series include:

This report, published in June 2008,

explores opportunities to improve the R&D

process. It proposes that new technologies

will enable the adoption of virtual R&D; and

by operating in a more connected world the

industry, in collaboration with researchers,

governments, healthcare payers and

providers, can address the changing needs

of society more effectively.

Published in February 2009, this paper

discusses the key forces reshaping the

pharmaceutical marketplace, including

the growing power of healthcare payers,

providers and patients, and the changes

required to create a marketing and sales

model that is fit for the 21st century. These

changes will enable the industry to market

and sell its products more cost-effectively,

to create new opportunities and to generate

greater customer loyalty across the

healthcare spectrum.

Published in June 2007, this paper

highlights a number of issues that will

have a major bearing on the industry by

2020. The publication outlines the changes

we believe will best help pharmaceutical

companies realise the potential the future

holds to enhance the value they provide to

shareholders and society alike.

“Pharma 2020: Challenging business models” is the fourth paper in the Pharma 2020 series on the future of the pharmaceutical industry to be

published by PricewaterhouseCoopers. This publication highlights how Pharma’s fully integrated business models may not be the best option for the

pharma industry in 2020; more creative collaboration models may be more attractive. This paper also evaluates the advantages and disadvantages of

the alternative business models and how each stands up against the challenges facing the industry.

All these publications are available to download at: www.pwc.com/pharma2020

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

Table of contents

Introduction 1

Profiting alone versus profiting together 1

Harking back to the future 2

Reading the signs 2

Broadening the value proposition and managing the value chain 4

Choosing between different collaborative models 6

The federated model•

The virtual variant of the federated model•

The venture variant of the federated model•

The fully diversified model•

Charting a successful course 12

Conclusion 13

Acknowledgements 15

References 17

Table of contents

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

1

Introduction

The pharmaceutical marketplace

is undergoing huge changes, as

we indicated in “Pharma 2020:

The vision”, the White Paper

PricewaterhouseCoopers* published in

June 2007.

1

These changes will have a

major bearing on the kind of business

models pharmaceutical companies

need to employ.

Most Big Pharma companies have

traditionally done everything from research

and development (R&D) through to

commercialisation themselves. But we

predict that, by 2020, this model will

no longer work for many organisations.

If they are to prosper, they will need to

improve their R&D productivity, reduce

their costs, tap the potential of the

emerging economies and switch from

selling medicines to managing outcomes

– activities few, if any, companies can

accomplish on their own.

Even the largest pharmaceutical

companies will have to collaborate with

other organisations to develop effective

new medicines more economically,

help patients manage their health and

ensure that the products and services

they provide really make a difference.

Moreover, they may have to step far

outside the sector to find some of the

partners they need.

We believe that two principal business

models – federated and fully diversified

– will emerge, as Pharma prepares for

the future. We also think that the current

economic downturn will accelerate

the shift to these new models, both by

reinforcing one of the key causal factors

– the pressure on healthcare payers

to maximise the value they get for the

money they spend – and by opening up

new opportunities to build or buy the

networks that will be required.

In the following pages, we shall look

at the main trends dictating the need

for a more collaborative approach. We

shall also evaluate the advantages and

disadvantages of the alternative business

models and how each stands up against

the challenges facing the industry.

Profiting alone versus

profiting together

Big Pharma’s traditional business model

hinges on the ability to identify promising

new molecules, test them in large clinical

trials and promote them with an extensive

marketing and sales presence (see

sidebar, What is a business model?). In

the predominant version of this model, a

single company may employ contractors

to supplement its own efforts, but it

seeks to generate profits on its own. In

essence, it pursues what might be called

a “profit alone” path.

But, by 2020, the strategy of

singlehandedly placing big bets on a

few molecules, marketing them heavily

and turning them into blockbusters will

not suffice. As J.P. Garnier, former chief

executive of GlaxoSmithKline, recently

pointed out, it is a “business model

where you are guaranteed to lose your

entire book of business every 10 to

12 years”.

2

More importantly still, it is a business

model that will no longer meet the

market’s needs. Management guru

Clay Christensen has convincingly

demonstrated how disruptive

innovations in various industries have

dismantled the prevailing business

model, by enabling new players to

target the least profitable customer

segments and gradually move upstream

until they can satisfy the demands of

every customer – at which point the old

business model collapses.

3

Pharma is currently undergoing just

such a period of disruptive innovation.

By 2020, most medicines will be

paid for on the basis of the results

they deliver – and since many factors

influence outcomes, this means that

it will have to move into the health

management space, both to preserve

the value of its products and to avoid

being sidelined by new players. If it is to

make groundbreaking new medicines

for which governments and health

insurers are prepared to pay premium

prices, it will also have to build the

relationships and infrastructure required

to ensure that it can get access to the

outcomes data they collect.

In short, the rules of the game are

shifting dramatically. And, as Michael

G. Jacobides, Associate Professor of

Strategic and International Management

at the London Business School, notes,

when an entire “industry architecture”

is transformed, it is not only “who does

what” that changes, it is also “who

takes what”.

4

By 2020, no pharmaceutical

company will be able to “profit

alone”. It will, rather, have to “profit

together”, by joining forces with a

wide range of organisations, from

What is a business model?

The term “business model” is used

to encompass a wide range of formal

and informal descriptions of the core

elements of a business. We have

used the term in the following sense:

“A company’s business model is the

means by which it makes a profit –

how it addresses its marketplace, the

offerings it develops and the business

relationships it deploys to do so.”

*‘PricewaterhouseCoopers’ refers to the network of member firms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each of which is a separate and

independent legal entity.

2 PricewaterhouseCoopers

academic institutions, hospitals and

technology providers to companies

offering compliance programmes,

nutritional advice, stress management,

physiotherapy, exercise facilities, health

screening and other such services.

Harking back to the

future

Of course, some pharmaceutical

companies have already tried to

collaborate with other organisations.

Rhone-Poulenc Rorer (now part of

sanofi-aventis) created RPR Gencell, the

world’s first biotechnology network, in

1994.

5

Many of the largest companies

also established disease management

programmes in the 1990s, although

most of them were not very successful

– primarily because healthcare

payers were sceptical about industry-

sponsored disease management.

6

So we are not suggesting that the

differences between these early efforts

and the business models that are likely

to prevail in 2020 will be completely

black and white. Nevertheless, we think

that two key differences will apply.

First, the technological and cultural

pre-conditions to facilitate collaboration

are now in place. In the mid-1990s, the

Internet was still in its infancy and many

of the tools that enable collaboration did

not exist. Today, however, such tools are

plentiful and the wider business culture

has changed dramatically. IBM, Apple,

Amazon and their ilk have demonstrated

the power of open platforms,

transformed corporate attitudes

towards networking and shown that it is

possible to reap much richer rewards by

profiting together than by profiting alone

(see sidebar, Apple’s core strategy of

collaboration).

7

Second, by 2020, collaboration

will be a “do or die” requirement

for pharmaceutical companies and

healthcare payers alike. It will be

essential for pharmaceutical companies

to develop effective new medicines

and address the demands of payers

increasingly well equipped to measure

what they are getting for their money;

and essential for payers to cope with

rapidly escalating healthcare costs.

Reading the signs

Various forces are changing the

environment in which Pharma operates

and the relative positions of the different

players in the healthcare arena. These

trends all point towards the need for

much greater collaboration (see Figure 1).

The global healthcare bill is soaring,

as the population ages, new medical

needs emerge and the disease burden

of the developing world increasingly

resembles that of the developed world.

Hence the fact that governments

and health insurers everywhere are

struggling to contain their expenditure.

The issue is further exacerbated by the

current economic turmoil that will put

even greater financial pressure on the

payer community.

Healthcare payers in the industrialised

economies are already mandating

what doctors can prescribe. The

British National Health Service has

also introduced a flexible pricing

scheme under which the prices of

new medicines can be lowered or

lifted, depending on the outcomes

they deliver.

8

And US President

Barack Obama’s administration is

moving towards opening up the US

market to much greater competition

from generics, as well as allowing the

importation of cheaper medications

from “safe” countries.

9

Apple’s core strategy of

collaboration

London Business School Professor

Michael G. Jacobides has recently

argued that successful companies do

not compete in a sector; they shape

the nature of a sector. They redefine

the part of the value chain they

occupy, and keep most of the value-

add through the intelligent design of

their collaboration with others in the

sector.

Thus collaboration is not just a tool

for doing the same things more

effectively. At its most powerful, it

can reshape an entire market, as

Apple has shown. Apple redefined the

mobile music sector by outsourcing

the production of the devices and

accessories, while retaining control of

the iTunes software. In other words,

it recognised that it could make

money by creating and orchestrating

a network of relationships – by

controlling, rather than owning.

Apple used three specific tactics

to change the rules of the game. It

enhanced the mobility of the parts

of the sector in which it has no

presence, by establishing a small

set of suppliers who know that they

can be replaced at any time. It made

itself into a bottleneck, by holding

onto the music format and ensuring

that files compatible with iPod can

only be played on iPod devices.

And it redefined who did what, by

encouraging other companies to

develop accessories rather than

entering the accessories market

itself. This has enabled it to benefit

from the efforts of those that support

its architecture, without making any

capital commitment itself.

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

3

The developing world will soon come

under equal pressure. The emerging

economies will experience the most

rapid growth in demand for medicines

over the next 11 years, but many (if not

all) of them will struggle to fund this

demand. The Chinese government has,

for example, undertaken to introduce

a universal healthcare system with a

level of cover that does not exceed

the country’s current economic

development. However, it is hard to see

how the plan will not entail a substantial

increase in China’s healthcare costs.

10

Healthcare payers in both the

developed and developing worlds are

also beginning to measure outcomes

much more carefully and to emphasise

the importance of prevention. By 2020,

they will expect the industry to go

“beyond the medicine” by providing

prophylactics and healthcare packages

designed to help patients manage their

health. Moreover, patients will play a

much bigger role in determining how

they are treated, as the money they

spend on medicines likewise rises

and the Internet gives them access to

more information. Armed with insights

Figure 1: The key trends now emerging and their implications for Pharma

Health and healthcare trends Scientific and technological trends

Pharma will need to go “beyond the

medicine”

R&D will need to go beyond the lab

Trends

Implications

Market trends

The Pharma and healthcare value chains

will become much more intertwined

Business models based on collaboration

• Pharma will be paid for outcomes,

not products

• Outcomes data will drive healthcare

policy

• Prevention will gain a higher healthcare

profile

• Pharma will need to offer “medicine-

plus” packages of care

• Pharma will have to adopt more flexible

pricing strategies

• Pharma will need access to outcomes

data

• Pharma will have to work with

technology vendors to virtualise R&D

• Pharma will need a wider, more

multi-disciplinary skills base

• Pharma will need to expand its

presence in Asia

• Pharma will need to demonstrate “real”

value-for-money

• Pharma will have to work more closely

with the regulators

• Pharma will have to collaborate with

payers and providers to perform

continuous trials

• Pharma will have to collaborate with

numerous service providers to deliver

packages of care

• R&D is becoming more virtualised

• The research base is shifting to Asia

• Remote monitoring is improving rapidly

• The burden of – and bill for – chronic

disease is soaring

• Healthcare payers are establishing

treatment protocols

• Pay-for-performance is on the rise

• The boundaries between different forms

of care are blurring

• Financial constraints on payers are

increasing

• Patients are becoming better informed

• Patients are picking up a bigger share

of the bill

• Demand for personalised medicine is

increasing

• Patients want cures, not treatments

• The emerging markets are becoming

more important

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

4 PricewaterhouseCoopers

gleaned from educational websites,

discussion groups and blogs, they will

not only want better, safer medicines,

they will also want a range of satellite

services they can tailor to their

individual needs.

If Pharma is to accommodate these

changes in the marketplace, it will have

to collaborate much more extensively

– as it will, indeed, to capitalise on

some of the scientific and technological

trends that are now emerging. The

research base is shifting, for example.

Non-OECD economies accounted for

18.4% of the world’s R&D in 2005, up

from 11.7% in 1996. The number of

patents filed by Asian researchers also

increased significantly over the same

period, albeit from low levels.

11

So the

industry will have to forge much closer

links with the most reputable centres of

scientific excellence in these countries.

Meanwhile, new technologies are

providing new sources of knowledge.

Home surveillance systems, portable

devices and implants, linked to online

and wireless networks, will facilitate

the monitoring of patients on a real-

time basis outside a clinical setting.

But if Pharma is to get access to the

outcomes data remote monitoring

generates, it will have to collaborate

with the hospitals and clinics that

capture this information.

Technological advances will likewise

enable the virtualisation of large parts

of the R&D process, as we explained in

“Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D”.

12

Some of

the leading pharmaceutical companies

are already exploring the potential of

semantic technologies and computer-

aided molecule design. Various

academic institutes and bioinformatics

firms are also building computer models

of different organs and cells, with the

ultimate aim of creating a “virtual man”.

But developing such a model will require

a monumental collaborative effort far

exceeding that required to complete the

Human Genome Project.

13

The economic case for change is

clear. The decline of revenue growth

and margins result in reduced

shareholder returns which will force

pharmaceutical companies to adapt.

There is a compelling case for increased

collaboration. Delivering drug therapies

to payers and patients in a 2020 world

will require new skills, technologies and

channels - the infrastructure required will

be uneconomic for anyone, other than

the largest players, to build internally.

To sum up, the key social, economic

and technological changes currently

taking place in the pharmaceutical and

healthcare arena will all necessitate the

development of multinational, multi-

disciplinary networks drawing on a

much wider range of skills than Pharma

alone can provide. The constraints

that previously hindered organisations

from collaborating over distance are

simultaneously evaporating – paving the

way for the use of new business models

(see sidebar, Emerging collaborative

networks).

14

In the next sections, we shall

look at the implications of broadening the

value proposition, the various models that

exist and the different opportunities and

risks they present.

Broadening the value

proposition and

managing the value chain

Pharma currently creates value by

developing new medicines (and a

relatively limited number of diagnostics).

Collaborating much more closely with

the key stakeholders in the healthcare

sector will enable the industry both

to expand its remit and to align its

Emerging collaborative networks

Several pharmaceutical firms

have already begun to use more

collaborative models. One such

instance is Lilly, which is currently

transforming itself from a traditional

fully integrated pharmaceutical

company into a fully integrated

pharmaceutical network, so that it can

draw on a wide range of resources

beyond its own walls. Lilly hopes that

teaming up with other organisations

to create virtual R&D programmes

will enable it to get better access to

innovation, reduce its costs, manage

risks more effectively and enhance

its productivity. For example, the

Chorus Project is a virtual organisation

to take molecules quickly to Proof

of Concept. Lilly also uses external

networks comprising third parties such

as Piramal Life Sciences, Hutchison

MediPharma, Suven Life Sciences for

the development of molecules.

Swiss biopharmaceutical development

specialist Debiopharm has pioneered a

more radical approach. The company

in-licenses promising new candidates

from academic institutes and biotech

companies, develops them and then

out-licences them to Big Pharma.

Debiopharm’s successes include three

products with combined global sales

of more than US$2.6 billion in 2007.

Most of the collaborative models that

currently exist are limited to R&D. But

it is easy to envisage various other

permutations, including networks

focusing on different therapeutic

areas and covering everything from

R&D through to sales and marketing;

networks focusing on different

enabling technologies, such as

genomics, proteomics and stem cell

research; and networks focusing

on the management of outcomes in

specific patient segments.

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

5

value chain more closely with those of

healthcare payers and providers.

As we indicated in more detail in

“Pharma 2020: Marketing the future”,

the value chains of the three parties

are heavily interdependent. The value

payers generate depends on the

policies and practices of the providers

they use. The value providers generate

depends on the revenues payers raise

and the medicines Pharma makes. And

the value Pharma generates depends

on getting access to the patients whom

providers serve and income from the

payers who fund those providers. Yet

the relationship between the different

players is often quite antagonistic and,

while they continue to clash, they are

struggling to retain their respective

goals.

15

If Pharma broadens its value

proposition, it can begin to close the

gap. Creating feedback loops to capture

outcomes data will help it to establish

a more dynamic relationship with

healthcare payers and providers. So,

too, will building the networks required

to deliver healthcare packages that

encompass a wide range of products

and services from numerous different

suppliers. This will ultimately result in

the convergence of the separate, linear

value chains that exist today and the

emergence of a single, circular value

chain (see Figure 2).

Patient

E

p

i

d

e

m

i

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

s

t

u

d

i

e

s

,

A

d

m

i

n

i

s

t

r

a

t

i

v

e

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

e

t

c

.

P

r

a

c

t

i

c

e

g

u

i

d

e

l

i

n

e

s

,

c

l

i

n

i

c

a

l

g

u

i

d

a

n

c

e

,

p

h

a

r

m

a

c

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

e

v

a

l

u

a

t

i

o

n

s

e

t

c

.

B

i

l

l

P

a

y

m

e

n

t

R

a

i

s

i

n

g

o

f

F

i

n

a

n

c

e

p

o

p

u

l

a

t

i

o

n

a

t

r

i

s

k

A

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

o

f

P

r

e

v

e

n

t

i

o

n

P

r

i

m

a

r

y

c

a

r

e

S

e

c

o

n

d

a

r

y

&

T

e

r

t

i

a

r

y

c

a

r

e

L

o

n

g

-

t

e

r

m

c

a

r

e

o

f

f

i

n

a

n

c

e

R

a

i

s

i

n

g

R

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

D

e

v

e

l

o

p

m

e

n

t

&

D

i

s

t

r

i

b

u

t

i

o

n

M

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

&

S

a

l

e

s

M

a

r

k

e

t

i

n

g

Payer

Provider

Pharma

R

a

i

s

i

n

g

p

r

e

m

i

u

m

s

o

r

t

a

x

e

s

,

C

o

l

l

e

c

t

i

n

g

o

u

t

-

o

f

-

p

o

c

k

e

t

p

a

y

m

e

n

t

s

R

e

f

e

r

r

a

l

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

,

m

o

n

i

t

o

r

i

n

g

&

p

a

y

m

e

n

t

o

f

h

e

a

l

t

h

c

a

r

e

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

r

s

’

b

i

l

l

s

M

e

d

i

c

a

l

S

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

M

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

P

r

o

v

i

s

i

o

n

o

f

C

o

v

e

r

Figure 2: By 2020, the pharmaceutical, payer and provider value chains will be much more closely intertwined

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

6 PricewaterhouseCoopers

Choosing between

different collaborative

models

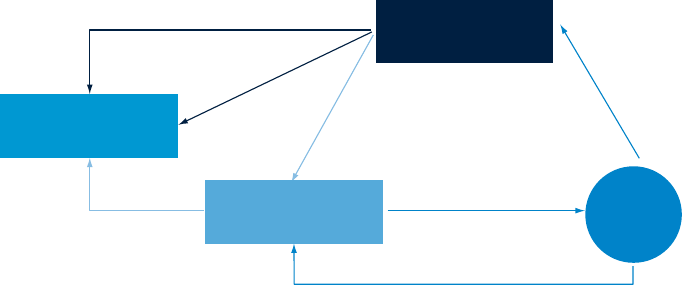

One vital question remains, however;

namely, what sort of model should

companies use to effect these changes?

We believe that two principal models

– federated and fully diversified – will

emerge. We have also identified two

variants of the federated model. In the

virtual version, a company outsources

most or all of its activities; in the

venture version, it manages a portfolio

of investments (see Figure 3). The two

models are not mutually exclusive. A

fully diversified company might choose

to use a federated model for certain

aspects of its business, and vice versa.

But we think that the federated model

will ultimately dominate, primarily

because it is quicker and more

economical to implement.

The federated model

In the federated approach, a company

creates a network of separate

entities with a common supporting

infrastructure. These might include

universities, hospitals, clinics,

technology suppliers, data analysis

firms and lifestyle service providers

based in numerous countries. They

might also include business units from

within the company itself, which it

places at “arm’s length” (see Figure 4).

The various participants have a mutual

goal – such as the management of

outcomes in a given patient population.

They also share funding, data, access

to patients and back-office services,

and this interdependence is the

glue that holds them together. They

are rewarded for their efforts using

measures like increased life expectancy

Virtual Variant

Venture Variant

Owned: Fully Diversified Model Collaborative: Federated Model

• Network of separate entities

• Based on shared goals & infrastructure

• Draws on in-house and/or external assets

• Combines size with flexibility

• Network of contractors

• Activities coordinated by one company

acting as hub

• Operates on project-by-project basis

• Fee-for-service financial structure

• Portfolio of investments

• Based on sharing of intellectual property/

capital growth

• Stimulates entrepreneurialism & innovation

• Spreads risk across portfolio

• Network of entities owned by one

parent company

• Based on provision of internally integrated

product-service mix

• Spreads risk across business units

Figure 3: The different business models

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

7

or quality-adjusted life years. And each

is rewarded in a manner that reflects

the evidence base for the contribution it

has made (see sidebar, How should the

cake be sliced?).

16

The federated model provides a

framework for creating integrated

packages of products and services, and

thus diversifying beyond a company’s

core offering. It also combines the

benefits of nimbleness and size. It

would enable each player to build a

specific area of expertise, establish a

competitive advantage as a result of

that expertise and sell its products,

knowledge or skills, leaving activities

that are better performed by others to

its partners within the federation.

More importantly still, the federated

model might encourage greater

cross-fertilisation and deliver bigger

improvements in performance, without

forfeiting any flexibility. The stronger

members of the network could help

the weaker ones to improve – since

federations have an incentive to perform

well as a whole – but they could also

replace any participant that persistently

underperforms.

Federation

T

e

c

h

n

o

l

o

g

y

G

e

n

e

r

i

c

s

C

o

m

p

l

i

a

n

c

e

M

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

C

e

n

t

r

e

s

W

e

i

g

h

t

F

i

t

n

e

s

s

C

l

u

b

s

C

o

m

p

a

n

y

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

i

e

s

C

l

i

n

i

n

c

s

H

o

s

p

i

t

a

l

s

P

h

y

s

i

o

t

h

e

r

a

p

y

A

n

a

l

y

s

t

s

D

a

t

a

S

u

p

p

l

i

e

r

s

C

a

l

l

C

e

n

t

r

e

M

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

e

r

s

P

h

a

r

m

a

c

e

u

t

i

c

a

l

C

e

n

t

r

e

s

Figure 4: The federated model

How should the cake be sliced?

It may sometimes be hard to measure

the value different participants have

created for two reasons. First, the

parties in any collaboration typically

value the contributions they have

made more highly than those of their

partners. This is a problem that can

be solved with watertight contracts,

robust performance indicators, good

governance and a proper audit trail.

Second, assessing the impact of

different forms of intervention can be

very difficult indeed.

Medicines, diet and exercise all play

a role in managing cardiovascular

disease, for example, but precisely how

much? Various studies have established

some parameters. They show, for

instance, that high-frequency exercise

can improve the cardio-respiratory

fitness of patients with heart disease

by at least 10% – and that, in turn,

can reduce the mortality rate by 15%.

We believe that many more studies

to evaluate the effectiveness of non-

pharmacological interventions will be

conducted in future, as healthcare

payers everywhere focus more heavily

on preventative measures.

This approach is essentially a more

complex variant of the co-development

and co-distribution agreements we have

today. In order for companies to work

better collaboratively it is essential to

define upfront measurable components

of delivery and value.

Defining the value provided by each

player in the federation will then inform

how each party should be rewarded -

this will be a combination of theoretical

analysis and monitoring of outcomes

and benefits to the patient. Clearly

to avoid the risk of litigation or the

constraints of exclusivity, the federation

needs to be underpinned by mutual

trust between all parties. However, there

are several examples of where this has

worked effectively such as a franchising

model where the value of a brand is

measured and rewarded.

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

Table of contents

8 PricewaterhouseCoopers

The virtual variant of the federated

model

In the virtual variant of the federated

model most or all of a company’s

operations are outsourced and the

company itself acts as a management

hub, coordinating the activities of

its partners (see Figure 5). Several

industries have already adopted

some aspects of this model. The

semiconductor industry typically

outsources its manufacturing in

order to concentrate on product

development, for example, and a

number of companies in the medical

devices sector are now following suit.

17

Similarly, strategic outsourcing of

design and manufacture to suppliers

has redefined manufacturing functions

within industries such as aerospace,

computing and electronics.

Most large pharmaceutical companies

also use external contractors to

supplement their in-house resources,

but very few firms have gone any

further (see sidebar, Shire’s virtual

vision).

18

There are very good reasons

why pharmaceutical companies should

outsource their R&D, manufacturing

and promotional activities where third

party alliances can provide a wider

range of opportunities, specialist

skills and market access. A pharma

company can then focus on the value

adding functions where they can

leverage on their relationships, scale

and market knowledge – i.e., project

management, business development,

regulatory affairs, intellectual property

management and the formation of good

relationships with key opinion leaders

Management

Hub

R

e

s

e

a

r

c

h

S

a

l

e

s

&

M

a

r

k

e

t

i

n

g

D

i

s

t

r

i

b

u

t

i

o

n

M

a

n

u

f

a

c

t

u

r

i

n

g

D

e

v

e

l

o

p

m

e

n

t

Figure 5: The virtual variant of the federated model

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

Shire’s virtual vision

Shire Pharmaceuticals is the epitome of a virtual company. It outsources almost

everything, from discovery to medical monitoring to data management to

statistics to medical writing. With the exception of its genetic therapy division,

every product it develops has been purchased from an outside source, via

in-licensing or acquisition.

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

9

and healthcare providers.

The virtual variant of the federated

model has other advantages, too. It

would enable companies to reduce

their initial capital outlay, convert

some of their fixed costs into variable

costs, utilise their resources more

efficiently and become more flexible.

Equally important, it might help the

industry leaders to expand into new

product/service areas or geographic

markets without resorting to further

mega-mergers (and thus facing the

huge challenges associated with

integrating two formerly separate

entities) or succumbing to the corporate

bureaucracy that so often strangles

innovation.

However, the virtual variant also comes

with some significant drawbacks.

The balance of power might shift to

suppliers, as it has done to a certain

extent in the automotive industry,

where a number of Tier 1 suppliers

now manage their own supply chains.

Alternatively, a major supplier might

get into financial difficulties and start

offering an inferior service or even

default on its obligations altogether.

But such risks can often be managed

by using multiple suppliers, wherever

possible.

Some pharmaceutical companies

might also see their earnings diluted,

since every participant in the value

chain would expect a return for the

services it provides. Theoretically, this

should not happen, since specialist

contractors typically have lower

costs than integrated pharmaceutical

companies. Indeed, according to one

study, a company that performs certain

preclinical development activities in-

house can expect to pay more than

double what it would pay if it completely

outsourced these activities to a third

party.

19

But a shortage of top-class

service providers or experts in particular

areas such as biological manufacturing

could drive prices up.

The venture variant of the

federated model

The venture variant of the federated

model entails investing in a portfolio of

companies in return for a share of the

intellectual assets and/or capital growth

they generate, rather than outsourcing

specific tasks. Special purpose vehicles

are sometimes used to manage such

investments, because they offer several

advantages in terms of risk sharing and

intellectual property protection.

A pharmaceutical company might

choose to concentrate its investments

in a particular therapeutic area or

spread them across a number of areas

in order to minimise its risk. At the end

of the investment period, it might either

claim the intellectual property that has

been generated or out-license it to a

third party. Alternatively, the originating

company (or companies) might retain

the intellectual property, commercialise

it and pay the sponsoring company a

return on its investment (see Figure 6).

GlaxoSmithKline has used a version

of the venture structure for many

years. SR One, its evergreen fund,

was established in 1985 and has

now invested more than US$500m in

some 30 private and public biotech

companies focusing on drug discovery,

development and delivery.

20

Other

Big Pharma companies, such as

Novartis and Pfizer, have also set up

corporate venture capital funds,

21

and AstraZeneca spun off part of its

gastrointestinal research operation

into a new company backed by a

consortium of private equity firms.

22

US investment bank Goldman Sachs

Generation of IP

Return of IP to growth company

Out-licensing/In-licensing

Out-licensing

Royalty payment

Investment

Return of IP to

pharmaceutical company

Pharmaceutical

company

Third party

IP

Growth

company

Figure 6: The venture variant of the federated model

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

10 PricewaterhouseCoopers

has already dipped a toe in the water

with its own venture fund (see sidebar,

Portfolio of pills).

23

Nevertheless, all these initiatives

are very small; between 2003 and

September 2006, corporate venture

capitalists invested just over US$1.5

billion in the US life sciences sector,

24

a fraction of the estimated US$11-

15 billion the member companies of

the Pharmaceutical Research and

Manufacturers of America spent on

discovery in 2006 alone.

25

Most such

ventures are also confined to research,

although the same approach could be

applied to development, manufacturing,

distribution, and marketing and sales.

So what might the venture variant

deliver, if it were implemented on a

much larger scale and extended to

other parts of the value chain? It would

alleviate the funding challenges in the

biotech sector, where companies often

struggle to raise a second or third

round of financing because venture

capitalists want to exit before they can

commercialise their products. These

challenges have been exacerbated by

the credit crunch and are likely to get

even worse in the current economic

recession.

26

It would also allow

promising start-ups to capitalise on

Big Pharma’s experience without being

stifled by a Big Pharma culture – both

trends which might stimulate greater

innovation.

Similarly, it would provide incentives for

traditional contract service providers to

make strategic, long-term investments –

as Lonza did, when it collaborated with

Genentech to build a manufacturing

plant in Singapore.

27

And it would

enable pharmaceutical companies to

explore numerous new avenues of R&D,

or expand their global manufacturing

and marketing capacity, without

investing too heavily in any one project.

However, venture structures are not

without their challenges. For a start,

the skills involved in managing a

portfolio of holdings are very different

from those involved in assessing and

pursuing potential research leads, as

is the timeframe venture capitalists

use to realise a return. So Big Pharma

would need to recruit people with the

necessary expertise and manage any

conflicting objectives very carefully.

Moreover, any company that operated

a large corporate venture capital fund

alongside its own research portfolio

would have to consider the financial

implications very carefully. R&D

expenditure is typically recorded on a

company’s profit and loss statement,

for example, whereas investments are

registered on the balance sheet and

subject to annual impairment reviews.

This has an impact on how companies

are taxed and on how they are valued

by the stock markets. Similarly, if

a company’s risk profile increases

because it has less control over research

that is conducted outside its own walls,

its cost of capital will increase.

Goldman Sachs has funded a

new “research pool” into which

pharmaceutical companies could

place a range of experimental

medicines in a single therapeutic area

in early-stage Phase I and II trials.

External experts, including scientists,

chemists and clinical research

organisations, would work alongside

scientists from the originating

companies. The bank argues that this

approach would reduce the costs

and bureaucracy associated with Big

Pharma. It might also allow competing

companies working on similar drugs

to pool their resources, rather than

duplicating each other’s efforts.

In April 2009, GSK and Pfizer

announced that they intend to

combine resources to set up a new

spin off firm dedicated to the HIV.

The structure of the deal gives a

majority 85% stake to GSK and 15%

to Pfizer with an increase of Pfizer’s

stake to 24.5% if all milestones are

reached. The new firm, with a current

revenue of £1.6 billion has a portfolio

of 11 products and a drug-discovery

pipeline of 17. R&D services will be

contracted directly from GSK and

Pfizer to develop these drugs with

investment from the new firm. In

return, the new firm will have exclusive

rights of first negotiation with respect

to HIV drugs developed by the two

pharma majors. The rationale for the

venture is that the new firm will be

more sustainable and broader as a

combined venture and that there are

synergies on the commercial side.

Portfolio of pills

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

11

The fully diversified model

The fully diversified model is one in

which a company expands from its

core business into the provision of

related products and services, such

as diagnostics and devices, generics,

nutraceuticals and health management

(see Figure 7). Johnson & Johnson

is Pharma’s leading exponent of this

approach. It is now the world’s largest

consumer health company, following

the US$16.6 billion acquisition of

Pfizer’s over-the-counter business

in December 2006.

28

It is also the

third-largest biologics and sixth-

largest pharmaceutical company, has

an extensive medical devices and

diagnostics operation,

29

and recently

started building a wellness and

prevention platform, with the purchase

of HealthMedia, a web-based “health

coach”.

30

A number of other companies are now

following suit. Novartis has spent nearly

US$25 billion beefing up its vaccines,

generics and eye-care products

operations over the past three years,

for example.

31

Roche is drawing on

its expertise in molecular diagnostics

to develop a consumer product test

for measuring indoor allergens.

32

And

GlaxoSmithKline has announced plans

to “diversify and de-risk” by focusing

more heavily on vaccines, consumer

health and the emerging markets.

33

The fully diversified model has several

merits, not least the fact that it enables

companies to reduce their reliance on

blockbuster medicines and spread their

risk by moving into other market spaces

with the potential to act as a bulwark

against generic competition. Like

the federated model, it also provides

a means of moving into outcomes

management by offering combined

product-service packages and playing

to the growing political emphasis on

prevention rather than treatment.

In addition to these advantages, it might

offer opportunities both to develop more

powerful brands and to acquire a better

corporate image. Numerous studies

show the extent to which Pharma’s

reputation has declined over the past

decade.

34

Supplementing its products with

“wellness” services might help a company

to create a more positive impression,

although it would have to handle its

relations with the regulators, healthcare

providers and patients very carefully.

Ethical

Pharmaceuticals

Diagnostics

& Devices

Generics

Consumer

Health

Health

Management

• Molecular testing

• Clinical biomarkers

• Medical devices

• Branded generics

• Commodity generics

• Super-generics

• Follow-on biologicals

• Over-the-counter

medicines

• Consumer

diagnostics

• Nutraceuticals

Mass-Market

• Primary-care

products (including

patches, inhalants

and controlled-release

implants)

• Poly-pills

Specialised-Market

• Biologicals

• Orphan drugs

• Vaccines

• Patient education

• Delivery and drug

administration

services

• Monitoring and

counselling

• Physiotherapy

• Nutritional advice

• Wellness

management

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

Figure 7: The fully diversified model

Table of contents

12 PricewaterhouseCoopers

However, the fully diversified model has

drawbacks, too. It requires a substantial

investment in new equipment, premises

and personnel, as well as major cultural

changes, since the provision of products

is very different from the provision of

services. It might also create new risks

by distracting management’s attention

from the core business – and even

alienate investors, who often prefer to

spread risk themselves.

Charting a successful

course

Clearly, the business model, or models,

a company chooses will depend on

its individual circumstances, including

the particular challenges it faces, the

expertise it possesses and the markets

in which it wants to operate. A company

that focuses exclusively on ethical

pharmaceuticals might find it harder

to diversify than one that is already

experienced in managing multiple

areas of activity, for example. Moreover,

federations typically place greater

demands on senior management than

conventional organisational hierarchies.

Creating and supervising a cross-

border, cross-disciplinary network

of external relationships can be very

time-consuming – and it is often

more difficult to identify, monitor and

manage risks. The various parties may

have different cultural characteristics,

different ways of communicating and

different expectations, some of which

may change over time. An individual

manager’s authority over the other

participants in the network is also likely

to be relatively limited. In a heavily

regulated industry such as Pharma, any

diminution of managerial control has

serious implications. So it is crucial to

establish clear goals and guidelines for

the governance and funding of such

arrangements, and for the division of

any intellectual assets they generate,

before signing on the dotted line.

Disrupting the existing order can

have a major impact on a company’s

short-term performance, too. When

GlaxoSmithKline established its Centres

of Excellence for Drug Discovery,

the upheavals the R&D function was

experiencing affected its pipeline for at

least 18 months.

35

We think that many companies which

choose the federated model will

therefore adopt a progressive approach.

They will start with opportunistic

alliances; use the most successful

alliances as building blocks to create

more strategic, longer-lasting coalitions;

and, finally, use the most successful

coalitions to create a fully federated

network of long-term partners (see

Figure 8). Taking incremental steps

will not only help them to identify the

organisations with which they can work

most effectively, but also give them

time to establish the technological

infrastructure that is essential to

manage the interfaces between two or

more different parties.

Most companies will also have to recruit

or train people with new skills. They will,

for example, need researchers who can

understand commercial imperatives;

financial analysts who can assess

different investment opportunities with

the discipline of venture capitalists;

senior executives who can negotiate

and oversee alliances; supply chain

managers who can supervise large

networks of service providers; and

health economists who can measure the

value of the contributions the respective

parties make. Those that choose to enter

the health management space directly

will also have to hire physiotherapists,

Opportunistic

Alliances

Strategic

Coalitions

Full

Federation

• Extended alliances

• Medium-term

• Three or more parties

• One-to-many

relationship

• Closer alignment

• Extended coalitions

• Long-term

• Many parties

• Many-to-many

relationship

• Complete alignment

• Ad-hoc

• Short-term

• Two parties

• One-to-one relationship

• Partial alignment

Figure 8: The path to federation is likely to be gradual

Source: PricewaterhouseCoopers

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

13

dieticians, counsellors and numerous

other people with skills that were

formerly outside Pharma’s domain.

Finding people with the appropriate

expertise will not be easy. Many

companies will therefore have to adopt

new talent management strategies, as

well as ensuring that the performance

measures and incentive systems they

use support the behaviour they want to

encourage.

Conclusion

Pharma’s fully integrated business

model enabled it to profit alone

for many years – and to profit very

successfully, as its track record in

rewarding shareholders shows. The

top companies saw their market

value soar 85-fold between 1985 and

2000.

36

But this model is now under

huge pressure and, by 2020, it will

not work. If the industry is to improve

its performance in the lab, reduce its

costs, serve the emerging markets

more effectively and make the transition

from producing medicines to managing

outcomes – as healthcare payers,

providers and patients are increasingly

demanding – it will have to collaborate

with other organisations, both inside

and outside the sector. It simply cannot

do everything itself. In addition there is

a clear economic rationale for greater

collaboration (See sidebar, Show me

the money).

Moreover, many companies will need to

move fast. As the healthcare landscape

changes and scientific expertise

becomes less important than the ability

to manage networks, the scope for

competition from new entrants will

increase. Several non-pharmaceutical

companies have already entered the

arena. Vodafone has, for example,

joined forces with Spanish telemedicine

provider Medicronic Salud and device

manufacturer Aerotel Medical Systems

to offer a wireless home monitoring

service.

37

Similarly, British insurance

Show me the money

There is plenty of evidence pointing to big opportunities for savings to be made through early intervention and tighter

management of patients and treatments. The federated model will make these savings more systematic and predictable,

rewarding participants based on the value that they create. Aligning risk and incentives appropriately is key to realising these

benefits. For example:

A study by the RAND Corporation estimated the financial savings from having 100% participation in disease management •

programmes for four diseases (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes and congestive heart failure) in

the US. They estimate the net savings to the health system to be $28bn (around 2% of total US health expenditure), with

additional benefits to the economy in terms of work days saved.

38

Britain’s Audit Commission examined the scale of adverse events in UK hospitals. They found that 10.8% of patients on •

medical wards experience an adverse event, 46% of which are preventable. One third of the adverse events lead to greater

morbidity or death and cost the UK’s NHS £1.1bn a year.

39

The five most costly conditions collectively account for 32.7% of overall healthcare expenditure. As we highlighted in •

“Pharma 2020: The vision”, improving patient compliance with enhanced treatment regimes by collaborating with other

support services is a key enabler to drive the healthcare bill down. Further, some commentators have suggested giving

patients financial incentives to improve compliance.

40

In 2009, Cisco Systems reported healthcare cost savings of $2.6m from a programme of on-site medical clinics covering 6,000 •

employees supported by integrated healthcare technology systems, chronic disease management, and health coaching.

41

14 PricewaterhouseCoopers

giant Prudential is collaborating with

Virgin Active Health Club to offer a

critical illness policy that provides

subsidised gym membership and

rewards people who exercise regularly

by reducing their premiums.

42

If the

leading pharmaceutical companies

cannot change their business models

rapidly, such firms may ultimately

feature more prominently on the

healthcare scene than they themselves.

The transition will not be easy, for

collaborative business models are

far more complex than the integrated

model that has previously prevailed.

Moreover, no one model will suit every

company. Each will need to assess

its position, options and future course

in light of its individual strengths and

needs (see sidebar, Key questions for

senior management).

However, the prospects for any

pharmaceutical company that can make

the switch are very promising. The

potential for reallocating resources to

deliver better outcomes and maximise

the effectiveness of expenditure

on healthcare is considerable in

most healthcare systems. Research

recently completed by Britain’s Audit

Commission shows, for example, that

annual spending on the treatment of

diabetes ranges from less than £8 to

over £30 (US$11.9-US$44.6) per head.

43

But differences in the prevalence of

diabetes account for only 8% of this

variation – and higher expenditure does

not result in fewer emergency hospital

admissions.

44

To date, Pharma has focused on the

profits it can earn from the estimated

10-15% of the health budget that goes

on medicines.

45

Yet there are many

opportunities to generate revenues

by improving the way on which the

remaining 85-90% is spent. It is these

opportunities the industry will need to

address in the brave new world of 2020.

Key questions for senior

management

What is our current business •

model? Does it play sufficiently to

our strengths?

What kind of company do we •

want our company to be?

Will our current business model •

enable us to expand into

new markets – be these new

products, services or countries

– and satisfy the expectations of

our customers in 2020? If not,

what sort of business model will

we need?

What is the size of the gap and •

how can we reduce it as rapidly

as possible?

Do we have a clear picture of the •

opportunities and risks entailed

by each of the alternatives

available to us?

Do we have a plan in place that •

will enable us to move forward

quickly, while maximising the

opportunities and minimising the

risks?

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

15

We would like to thank the many people at PricewaterhouseCoopers who helped us to develop this report. We would also like

to express our appreciation for the input we received from clients and our particular gratitude to the following external experts

who so generously donated their time and effort to the project;

Adrian Rawcliffe, Senior Vice President Worldwide Business Development, GlaxoSmithKline Plc.

Dr Dennis B Gillings, Chairman of the Board and Founder, Quintiles Transnational Corp.

Dr Genghis Lloyd-Harris, Partner, Abingworth

Gino Santini, Senior Vice President, Corporate Strategy and Policy, Eli Lilly and Co.

John Fowler, Head of Healthcare Investment Banking Team in Europe, Deustche Bank AG

Dr John Murphy, European Pharmaceuticals Analyst, Goldman Sachs Group, Inc.

Laurent Massuyeau, Head of Business Development, Addex Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Professor Michael Jacobides, London Business School

Dr Vincent Mutel, Chief Executive Officer, Addex Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

The views expressed herein are personal and do not reflect the views of the organisations represented by the individuals

concerned.

Acknowledgements

Table of contents

Pharma 2020:

Challenging business models

17

PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Pharma 2020: The vision – Which path will you take?” (June 2007). 1.

Kathryn Phelps, “Mergers May Buy Time, But Fundamental Changes Necessary, GSK’s Garnier”, 2. The Pink Sheet (February 26, 2007), p. 11.

Clayton M. Christensen, “The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail” (Boston: Harvard Business Press, 1997).3.

Michael G. Jacobides, Thorbjørn Knudsen & Mie Augier, “Who Does What and Who gets What: Capturing the Value from Innovation”, AIM 4.

Executive Briefing (2006), accessed July 27, 2009, http://faculty.london.edu/mjacobides/assets/documents/JKAbriefingAIMnov06.pdf

“Rhône-Poulenc Forms Network To Develop Gene and Cell Therapies”,5. Oncology News International, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January 1, 1995), accessed

December 8, 2008, http://www.cancernetwork.com/display/article/10165/97578

The Boston Consulting Group, “Realizing the Promise of Disease Management: Payer Trends and Opportunities in the United States” (February 6.

2006), p. 9.

Michael G. Jacobides, Thorbjørn Knudsen & Mie Augier, “Benefiting from Innovation: Value Creation, Value Appropriation and the Role of Industry 7.

Architectures”, Research Policy, Vol. 35 (2006): 1200-1221.

BBC News, “Deal reached on NHS drug prices” (November 19, 2008), accessed November 28, 2008, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/7737027.stm8.

“Barack Obama and Joe Biden’s plan to lower health care costs and ensure affordable, accessible health coverage for all” (2008), accessed 9.

November 10, 2008, http://www.barackobama.com/pdf/issues/HealthCareFullPlan.pdf

James J. Shen, “Will China’s healthcare reform save the day?” 10. Pharma China, Issue 27 (November 2008), pp. 2-5.

OECD, “OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2008: Highlights” (2008), accessed December 22, 2008, http://www.oecd.org/11.

dataoecd/18/32/41551978.pdf

PricewaterhouseCoopers “Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D – Which path will you take?” (June 2008)12.

For an extensive discussion of these trends, please see “Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D”.13.

Lilly website, accessed December 8, 2008, http://www.lilly.com/about/partnerships/; and Debiopharm Group website, accessed December 8, 14.

2008, http://www.debiopharm.com/business-model.html

PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Pharma 2020: Marketing the future – Which path will you take?” (February 2009)15.

University of Florida Health Science Center media release, “Walk this way: UF research provides insight into heart healthy exercise regimen” 16.

(November 14, 2005), http://news.health.ufl.edu/news/story.aspx?ID=2846

David Busch, “Can History Repeat Itself? The Case for the Virtual Medical Device OEM”, 17. Medical Product Outsourcing (December 2007),

accessed February 21, 2008, http://www.mpo-mag.com/articles/2007/11/can-history-repeat-itself

Kenneth Eng, David C. Izard & Terek J. Peterson, “Managing the CRO Relationship to Effectively Request and Receive CDISC STDM and ADaM 18.

Deliverables”, SAS PharmaSUG Proceedings (Atlanta, Georgia: June1-4, 2008), accessed December 12, 2008, http://www.lexjansen.com/

pharmasug/2007/fc/fc06.pdf

SRI International, “Capital and Time Efficiencies from Outsourcing Preclinical Development” (2005), accessed March 10, 2008, http://www.sri.19.

com/biosciences/pdf/OutsourcingPrecelinicalDevelopment.pdf

SR One website, accessed December 14, 2008, http://www.srone.com/20.

Lisa M. Jarvis, “Thinking Outside The Big Pharma Box”, 21. Chemical & Engineering News (May 7, 2007), accessed February 20, 2008, http://

pubs.acs.org/cen/coverstory/85/8519cover2.html; and Associated Press, “Pfizer expands venture capital program” (August 1, 2007), accessed

February 20, 2008, http://www.boston.com/business/articles/2007/08/01/pfizer_expands_venture_capital_program/

Jonathan Russell, “AstraZeneca spins off research”, 22. The Telegraph (February 15, 2008), accessed March 9, 2008, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/

money/main.jhtml?xml=/money/2008/02/15/cnastra115.xml

Andrew Jack, “Goldman unveils plans for pharma research funding”, The 23. Financial Times (December 3, 2008), accessed December 12, 2008,

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/e92f9d3c-c0db-11dd-b0a8-000077b07658.html?nclick_check=1

PricewaterhouseCoopers/National Venture Capital Association MoneyTree Report based on data from Thomson Financial. 24.

The member companies of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America spent about US$43 billion on R&D in 2006. Datamonitor 25.

estimates that discovery accounts for between 25% and 35% of these costs. For further information, see Pharmaceutical Research and

Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), “R&D Spending by U.S. Biopharmaceutical Companies Reaches a Record $55.2 Billion in 2006” (February

12, 2007), accessed February 20, 2008, http://www.phrma.org/news_room/press_releases/r&d_spending_by_u.s._biopharmaceutical_companies_

reaches_a_record_$55.2_billion_in_2006/; and Datamonitor, “Pharmaceutical Outsourcing Part 2: An Introduction to Drug Discovery Strategies”

(August 2006).

References

18 PricewaterhouseCoopers

Andrew Jack, “Drugmakers sweeten deals for biotech groups”, The 26. Financial Times (September 19 2008), accessed December 21, 2008, http://

www.ft.com/cms/s/0/9d620a56-85d6-11dd-a1ac-0000779fd18c,dwp_uuid=aece9792-aa13-11da-96ea-0000779e2340.html

Jim Miller, “The Art of the Deal”, 27. BioPharm International (September 1, 2008), accessed December 10, 2008, http://biopharminternational.

findpharma.com/biopharm/GMPs%2FValidation/The-Art-of-the-Deal/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/545356

Andrew Ross Sorkin & Stephanie Saul, “J&J buys Pfizer unit for $16.6 billion”, 28. International Herald Tribune (June 26, 2006), accessed November 3,

2007, http://www.iht.com/articles/2006/06/26/business/pfizer.php

Johnson & Johnson website, accessed December 11, 2008, www.jnj.com/connect/about-jnj29.

Johnson & Johnson press release, “Johnson & Johnson Establishes Wellness & Prevention Platform with Acquisition of HealthMedia, Inc.” 30.

(October 27, 2008), accessed December 11, 2008, www.jnj.com/connect/news/corporate/20081027_151000

Sarah Rubenstein, “Novartis Spends Big on Diversification”, The Wall Street Journal Health Blog (April 7, 2008), accessed December 21, 2008, 31.

http://blogs.wsj.com/health/2008/04/07/novartis-spends-big-on-diversification/

Reuters, “National Jewish Health and Roche Diagnostics Corporation Reach Agreement to Pursue Environmental Molecular Diagnostics 32.

Opportunities” (September 10, 2008), accessed December 11, 2008, http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS134552+10-Sep-

2008+PRN20080910

Andrew Jack, “GSK chief pushes for expansion into new markets”, The 33. Financial Times (June 13, 2008), accessed December 21, 2008, http://

www.ft.com/cms/s/0/617a6ef8-38e1-11dd-8aed-0000779fd2ac.html?nclick_check=1

PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Pharma 2020: The vision”, pp. 24-25.34.

Robert S. Huckman & Eli P. Strick, “GlaxoSmithKline: Reorganizing Drug Discovery (B)”, 35. Harvard Business Publishing (May 17, 2005). Available for

order at http://harvardbusinessonline.hbsp.harvard.edu/b01/en/common/item_detail.jhtml?id=605075

Milken Institute, “Financial innovations for Accelerating Medical Solutions”, Vol. 2 (October 2006), accessed December 15, 2008, http://www.36.

milkeninstitute.org/pdf/fin_innov_vol2.pdf

Aerotel Medical Systems media release, “Aerotel and Medicronic-Vodafone Launch Innovative Wireless Homecare System in Spain” (April 4, 37.

2008), accessed December 8, 2008, http://www.openpr.com/news/41301/Aerotel-and-Medicronic-Vodafone-Launch-Innovative-Wireless-

Homecare-System-in-Spain.html

Bigelow JH et al “Analysis of healthcare interventions that change patient trajectories”, 38. The RAND Corporation, 2005, pg xxvi

Audit Commission “A spoonful of sugar: Medicines management in NHS hospitals”, December 2001, pg 1939.

For example, Giuffrida A and Torgerson DJ, “Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance”. 40. British

Medical Journal 1997 315: 703-707

Cathy Weselby, “Improving health at the office”,41. Silicon Valley/San Jose Business Journal, accessed January 12, 2009, http://sanjose.bizjournals.

com/sanjose/stories/2009/01/12/story2.html

Helen Loveless, “The comeback kid’s medical cover”, 42. Mail on Sunday (October 29, 2007), accessed October 15, 2008, http://www.thisismoney.

co.uk/insurance/health-insurance/article.html?in_article_id=425744&in_page_id=39

Based on the midmarket exchange rate of £1.00 to US$1.48474 on December 22, 2008.43.

Audit Commission, “Health Data Briefing No. 12. Spending on disease: Diabetes” (September 2008), accessed December 15, 2008, http://www.44.

audit-commission.gov.uk/Health/Downloads/HealthDataBriefing_spendingondiabetes.pdf

Total expenditure on pharmaceuticals and other medical non-durables expressed as a percentage of total healthcare expenditure ranges from 45.

12.4% to 29.7% in the OECD countries. On average, it is thought to represent about 15% of the global health budget. For further information on

healthcare expenditure in the OECD countries, see OECD Health Data 2008 (October 2008).

Territory contacts

Argentina

Diego Niebuhr

[54] 11 4850 4705

Australia

John Cannings

[61] 2 826 66410

Belgium

Thierry Vanwelkenhuyzen

[32] 2 710 7422

Brazil (SOACAT)

Luis Madasi

[55] 11 3674 1520

Canada

Gord Jans

[1] 905 897 4527

Czech Republic

Radmila Fortova

[420] 2 5115 2521

Denmark

Torben TOJ Jensen

[45] 3 945 9243

Erik Todbjerg

[45] 3 945 9433

Finland

Janne Rajalahti

[358] 3 3138 8016

Johan Kronberg

[358] 9 2280 1253

France

Jacques Denizeau

[33] 1 56 57 10 55

Germany

Volker Booten

[49] 89 5790 6347

India

Sharat Bansal

[91] 22 6669 1538

Ireland

John M Kelly

[353] 1 792 6307

Enda McDonagh

[353] 1 792 8728

Israel

Assaf Shemer

[972] 3 795 4681

Italy

Massimo Dal Lago

[39] 045 8002561

Japan

Kenichiro Abe

[81] 80 3158 5929

Luxembourg

Laurent Probst

[352] 0 494 848 2522

Mexico

Ruben Guerra

[52] 55 5263 6051

Netherlands

Arwin van der Linden

[31] 20 5684712

Poland

Mariusz Ignatowicz

[48] 22 523 4795

Portugal

Ana Lopes

[351] 213 599 159

Russia

Alina Lavrentieva

[7] 495 967 6250

Singapore

Abhijit Ghosh

[65] 6236 3888

South Africa

Denis von Hoesslin

[27] 117 974 285

Spain

Rafael Rodríguez Alonso

[34] 91 568 4287

Sweden

Liselott Stenudd

[46] 8 555 33 405

Switzerland

Clive Bellingham

[41] 58 792 2822

Peter Kartscher

[41] 58 792 5630

Markus Prinzen

[41] 58 792 5310

Turkey

Ediz Gunsel

[90] 212 326 6060

United Kingdom

Andy Kemp

[44] 20 7804 4408

Table of contents

This publication has been prepared for general guidance on matters of interest only, and does not constitute professional advice. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication

without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and, to the

extent permitted by law, PricewaterhouseCoopers does not accept or assume any liability, responsibility or duty of care for any consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance

on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it.

© 2009 PricewaterhouseCoopers. All rights reserved. ‘PricewaterhouseCoopers’ refers to the network of member firms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each of which is a separate and

independent legal entity.

For further information, please contact:

pwc.com/pharma

Global

Simon Friend

Partner, Global Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences

Industry Leader

PricewaterhouseCoopers (UK)

[44] 20 7213 4875

Steve Arlington

Partner, Global Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences Advisory

Services Leader

PricewaterhouseCoopers (UK)

[44] 20 7804 3997

Michael Swanick

Partner, Global Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences Tax Leader

PricewaterhouseCoopers (US)

[1] 267 330 6060

United States

Anthony Farino

Partner, US Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences Advisory

Services Leader

PricewaterhouseCoopers (US)

anthony[email protected]

[1] 312 298 2631

Mark Simon

Partner, US Pharmaceutical and Life Sciences Industry Leader

PricewaterhouseCoopers (US)

[1] 973 236 5410

Middle East