1

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennes-

see;

2

New York University Medical Center,

Hospital for Joint Diseases, New York,

New York;

3

Drexel University College of

Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

USA.

Supported in part by grants from the

A rthritis Foundation, the Jack C. Massey

Foundation and Abbott Immunology.

T h e o d o re Pincus, MD; Yusuf Yazici, MD;

Martin Bergman, MD.

Please address correspondence to:

Theodore Pincus, MD, Professor of

Medicine, Division of Rheumatology and

Immunology, Vanderbilt University School

of Medicine, 203 Oxford House, Box 5,

Nashville, TN 37232-4500, USA.

E-mail: [email protected]

Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23 (Suppl. 39):

S19-S28.

© Copyright CLINICALAND EXPERIMENTAL

RHEUMATOLOGY 2005.

Key words: MDHAQ, HAQ,

activities of daily living.

ABSTRACT

The HAQ has become the pre-eminent

patient questionnaire used in rheuma -

t o l o g y. It is easily completed by patients,

but not easily reviewed and scored in

s t a n d a rd clinical care and has some

minor psychometric limitations, as do

all questionnaires. Modifications of the

HAQ been made to facilitate use in

standard care, particularly to include

8-10 activities of daily living, along

with scores for pain and global status

and other information on one side of

one page for rapid review by the clini -

cian. A patient questionnaire for stan -

dard care should be limited to 2 sides

of 1 page, in a format amenable to

“eyeball” review by the clinician in 5

seconds or less. It can be scored for -

mally in 15-20 seconds or less, and is

useful in patients with all rh e u m a t i c

diseases.

The current version of a multi-dimen -

sional HAQ (MDHAQ) includes scor -

ing templates on the questionnaire to

allow formal scoring in less than 15 se -

conds by a rheumatologist or an assis -

tant, for possible entry onto a paper

and/or computerized flow sheet. Vari -

ous versions of the MDHAQ may also

include a "constant" region of physical

function, pain and patient global sta -

tus, and "variable" regions of fatigue,

morning stiffness, psychological dis -

tress, change in status, a review of sys -

tems, a rheumatoid arthritis disease ac -

tivity self-report joint count (RADAI),

review of recent health events, and re -

view of medications. The MDHAQ can

be used in the infrastructure of rheu -

matology care to include quantitative

data in standard care of all patients

with all rheumatic diseases.

Introduction

Over the last 25 years, since its land-

mark publication in April 1980, the

Health Assessment Questionnaire

(HAQ) (1) has become the pre-eminent

patient questionnaire in rheumatology.

The HAQ queries 20 activities of daily

living (ADL) (Table I) for which the

patient is asked to respond in 4 cate-

gories as to whether he or she can per-

form the activity “without any difficul-

ty” (= 0), “with some difficulty” (= 1),

“with much difficulty” (= 2), and

“unable to do” (= 3) (2). The 20 activi-

ties are classified into 8 categories of 2

or 3 each. The HAQ also queries the

use of 16 aids and devices. A score for

each of the 8 categories is based on the

maximum score for any of the 2 or 3

activities in the category, with an

increase in the score by 1 for any cate-

gory in which patients use an aid or

device. The total score is the mean of

the scores for the 8 categories (1). The

HAQ is discussed in detail in this Sup-

plement by its developer, James Fries

with Bonnie Bruce (3).

Some limitations of the HAQ

The HAQ has proven a major advance

in rheumatology clinical research.

However, as is the case with all mea-

surement methods, certain limitations

are seen, which are not of major conse-

quence but may detract from its psy-

chometric validity (Table I). A HAQ

score may be increased artefactually by

a rheumatologist recommending a

device to aid a patient’s function; for

example, if a patient responds that she

walks, opens jars, or performs another

activity “with some difficulty”, and is

given a cane, jar opener, or other de-

vice, but continues to respond “with

some difficulty”, the score will be

increased from 1 to 2, even though the

p a t i e n t ’s physical function may be

improved.

Different activities may determine the

HAQ scores on different completions,

as only 1 of 2 or 3 activities within each

category determines the score for the

category. The categories of the HAQ do

not necessarily group related activities

S-19

Development of a multi-dimensional health assessment

questionnaire (MDHAQ) for the infrastructure of standard

clinical care

T. Pincus

1

, Y. Yazici

2

, M. Bergman

3

S-20

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

effectively; “stand up from a straight

chair” in the category of “arising” and

“get on and off the toilet” in the catego-

ry of “hygiene” are correlated at higher

levels of significance with one another

than with the other activities within the

categories of “arising” and “hygiene

(4). A patient may hypothetically im-

prove on 1 to 12 of the 20 activities on

the HAQ, but show no change in HAQ

score.

Floor effects are seen, namely that

patients may have normal HAQ scores,

but nonetheless feel that there exist

functional limitations. A change in

score of a given interval, say from 0.25

to 0.5, may not represent a similar

change as a change from 0.25 to 1.5

(5). As noted, none of these matters

limit the HAQ severely in the docu-

mentation and monitoring of status in

clinical trials, and in predicting work

disability and mortality in observation-

al clinical research, as the HAQ or a

derivative – rather than a joint count,

laboratory test or radiograph – is the

best predictor in rheumatoid arthritis

(RA) of functional status (6, 7), work

disability (8-10), costs (11), joint

replacement surgery (12) and prema-

ture death (6, 13-19).

The HAQ is generally easily completed

by most patients in 5-10 minutes. How-

ever, pragmatic considerations may li-

mit use of the HAQ in standard clinical

care, as few clinicians – with some

notable exceptions such as Dr. Freder-

ick Wolfe (20) – use the HAQ routine-

l y. Some HAQ activities, such as

“shampoo your hair” and “do chores

such as vacuuming or yard work” are

not performed by some patients, caus-

ing some interruption in completion by

some patients. Since the HAQ involves

2 sides of 1 page, it cannot be quickly

reviewed (“eyeballed”) by a clinician

to get a simple overview of patient sta-

tus. The scoring system is somewhat

complex, generally requiring at least a

minute. The HAQ does not include

data concerning psychological distress,

fatigue, change in status, morning stiff-

ness, or other constructs which some

clinicians may wish to monitor in stan-

dard care.

These considerations have led to efforts

to develop simpler patient question-

naires for use in standard clinical care,

in a more easily scored format, which

can be scanned (“eyeballed”) by a clin-

ician in 5 seconds or less, scored in less

than 10-20 seconds, and that provide

additional information concerning psy-

Table I. Items included on the HAQ, 8 ADLMHAQ, 14 ADLMDHAQ, 10 ADLMDHAQ

and HAQII. (The codes of the items are the same as used in other tables).

HAQ 8 ADL 14 ADL 10 ADL HAQII

MHAQ MDHAQ MDHAQ

(1) (4) (24) (2) (5)

DRESSING & GROOMING:

Dress yourself, including tying shoelaces

and doing buttons ? 1a a a a

Shampoo your hair ? 1b - - -

ARISING:

Stand up from a straight chair ? 2a - - - √

Get in and out of bed ? 2b b b b

EATING:

Cut your meat ? 3a - - -

Lift a full cup or glass to your mouth ? 3b c c c

Open a new milk carton ? 3c - - -

WALKING:

Walk outdoors on flat ground ? 4a d d d √

Climb up 5 steps ? 4b - - -

Walk 2 miles or 3 kilometers ? - - i i

HYGIENE:

Wash and dry your entire body ? 5a e e e

Take a tub bath ? 5b - - -

Get on and off the toilet ? 5c - - - √

REACH:

Reach and get down a 5 pound object

from above your head ? 6a - - - √

Bend down to pick up clothing from the floor ? 6b f f f

GRIP:

Open car doors ? 7a - - - √

Open previously opened jars ? 7b - - -

Turn regular faucets on and off ? 7c g g g

OTHER ACTIVITIES:

Run errands and shop ? 8a - k -

Get in and out of a car, bus, train, or airplane ? 8b h h h

Do chores such as vacuuming or yard work ? 8c - - -

Participate in sports and games as you would

like ? - - j j

Climb up a flight of stairs ? - - l -

Run or jog two miles ? - - m -

Drive a car 5 miles from your home ? - - n -

PSYCHOLOGICALSTATUS:

Get a good night’s sleep ? - - o o

Deal with the usual stresses of daily life ? - - p p

Deal with feelings of anxiety or being

nervous ? - - q -

Deal with feelings of depression of feeling

blue ? - - r -

HAQII ITEMS NOTLISTED ABOVE

Go up two or more flights of stairs ? √

Lift heavy objects ? √

Move heavy objects ? √

Wait in line for 15 minutes ? √

Do outside work (such as yard work) ? √

Source: Reference (2)

chological status, fatigue, change in sta-

tus, morning stiffness, review of systems,

medications used, all on 2 sides of 1

page. The modified HAQ (MHAQ) and

multi-dimensional HAQ (MDHAQ)

were developed to meet these goals.

Development of a modified HAQ

(MHAQ)

A modified HAQ (MHAQ) was des-

cribed in 1983 (4), which includes 8

activities of daily living, 1 from each

category of the HAQ (Table I), with no

aids and devices, for rapid review by a

clinician and scoring in less than half

the time needed for the HAQ. MHAQ

scores are correlated significantly with

HAQ scores (as would be expected for

the same items) (4), and with tradition-

al joint counts, radiographs and labora-

tory indicators of inflammation (21).

The MHAQ appears to be as sensitive

as the HAQ in clinical trials to recog-

nize differences between active and

control treatments (22), and as infor-

mative in longitudinal clinical studies

of morbidity (17), mortality (16, 17)

and work disability (8) in RA. T h e

MHAQ also includes 10 cm visual ana-

log scales for pain and global status, to

assess the 3 patient questionnaire mea-

sures on the ACR Core Data Set (23).

The activities chosen for the MHAQ

were generally the simplest of the 2 or

3 within each HAQ category (Table I),

as the deleted activities were some that

certain patients do not perform, such as

“shampoo your hair”, “vacuuming or

yard work”, or “take a tub bath.”

Therefore, MHAQ scores were system-

atically 0.3–0.4 units lower than HAQ

scores, and “floor effects,” i.e., scores

of 0 in people who had some functional

d i s a b i l i t y, were more common than

seen on the HAQ (24). This problem

became more prominent during the

1990s as the status of patients with RA

improved substantially with the aggres-

sive use of low dose methotrexate and

low dose prednisone (25).

Development of a multi-dimensional

HAQ (MDHAQ)

The lower scores with a greater level of

“floor effects” of the MHAQ compared

to the HAQ was addressed by the addi-

tion of 6 complex activities in a multi-

dimensional HAQ (MDHAQ) (Table I)

(24). The term “multi-dimensional” is

used in recognition that the question-

naire had been further modified over

the years to include not only the queries

of 8-10 activities of daily living, and

visual analog scales for pain and global

status from the ACR Core Data Set (23,

26, 27), but also scores for fatigue, psy-

chological distress, morning stiff n e s s

and change in status on one side of one

page, and review of systems and medi-

cations on the reverse side of the page.

The additional activities reduced the

number of patients with floor effects

from 16% on the HAQ and 30% on the

MHAQ, to less than 3% on the MD-

HAQ.

More recently, a further revision of the

MDHAQ with only 2 of 6 additional

activities, “walk 2 miles or 3 kilo-

meters” and “participate in recreation

and sports as you would like,” has been

reported (Table I) (2). This format fur-

ther advanced ease of scoring, as scores

for 10 activities may be divided by 10

and scored 0-3, as in the HAQ, or divi-

ded by 3 and scored 0-10, so that scores

for functional disability are scored 0-

10, as are scores for pain, global status

and fatigue (2). The prevalence of floor

effects was 10%, but most patients with

a score of “0” were in a clinical remis-

sion status.

The initial report of the MDHAQ

included 4 items to address psycholog-

ical distress, including anxiety, depres-

sion, sleep and dealing with stress (24),

in the patient-friendly HAQ format of 4

response items – “without any difficul-

ty, “with some difficulty,” “with much

difficulty,” “unable to do.” The depres-

sion item was found to be correlated

significantly with the Beck Depression

Inventory and Centers for Epidemio-

logic Studies Depression Inventory

(CES-D), which takes up a page or

more (r > 0.6, p < 0.001). In the revised

MDHAQ (2), scores for psychological

distress were found to be similar with

removal of the “stress” item, and 3

items for anxiety, depression and sleep

have been retained. Each item is scored

on a 0 to 3.3 scale, 0 = with no difficul-

ty, 1.1 = with some difficulty, 2.2 =

with much difficulty, and 3.3 = unable

to do. The total score for this psycho-

logical distress scale is the total of the 3

items, i.e. 0 – 9.9, again giving a total

near 10 as for the other scales.

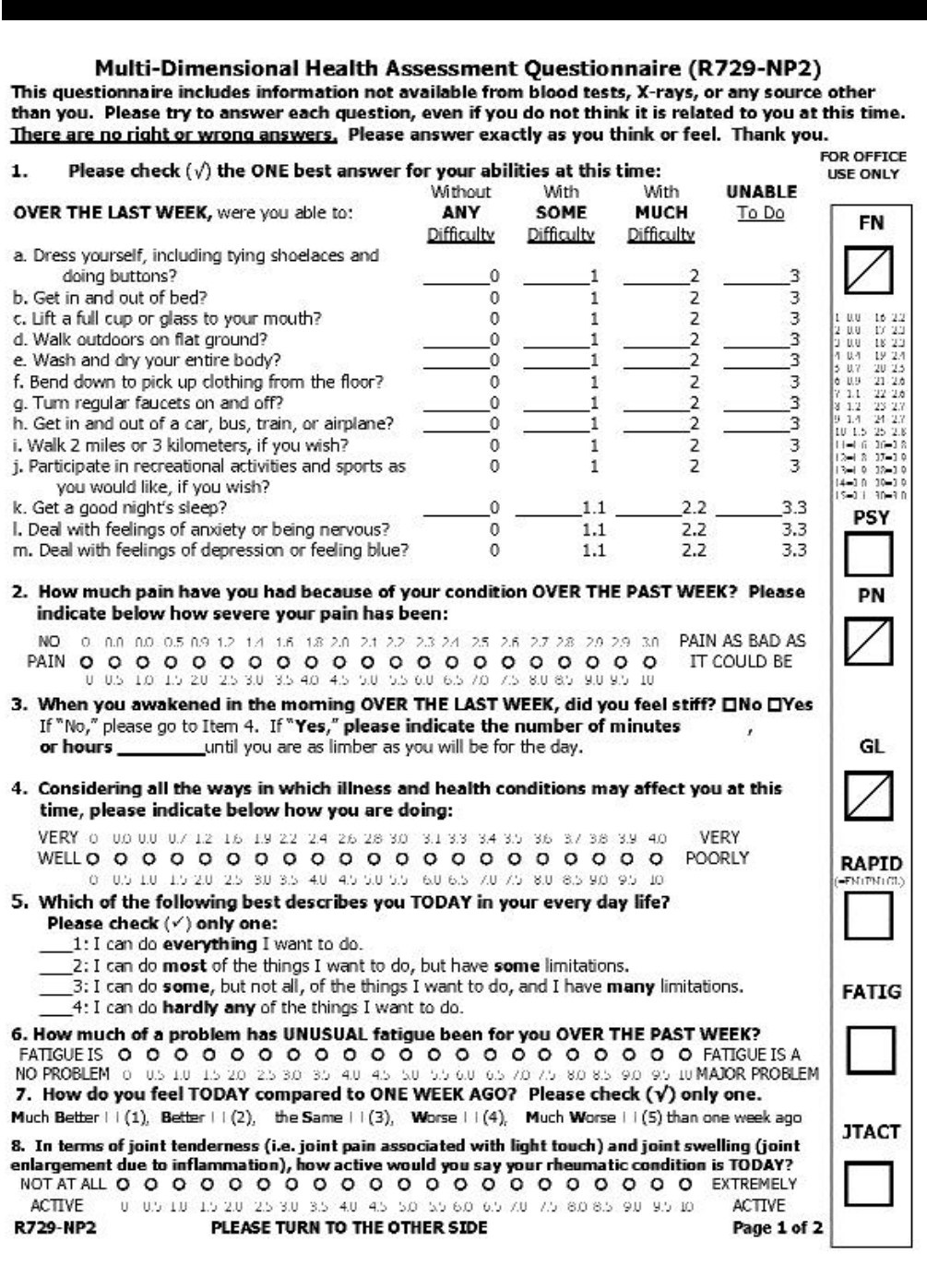

The recently reported MDHAQ (Fig. 1)

includes 7 scores: physical function,

pain, global status, psychological dis-

tress, and fatigue, each of which is

scored 0-10 (or 0-3 for physical func-

tion, if preferred), as well as change in

status and morning stiffness in minutes,

all on 1 side of 1 page which can be

easily scanned in 5 seconds to gain an

overview of a patient’s situation. While

it is pragmatically desirable that the

same questionnaire be completed by

each patient within each clinical set-

ting, it is not necessary that every pa-

tient questionnaire used in every rheu-

matology setting be identical. All ver-

sions of the MDHAQ (available at

website mdhaq.org) include a “con-

stant” region, analogous to immuno-

globulins, of physical function, pain,

and global status, the 3 patient self-

report measures from the ACR Core

Data Set (23), as well as strongly en-

couraged and optional “variable” re-

gions. “Variable” regions regarded as

“strongly encouraged” include scales

for psychological distress, fatigue,

change in status, morning stiffness, and

an RADAI-self-report joint count

(Table II). “Variable” regions regarded

as “optional” include (Table II): a re-

view of systems list of medications

used, recent medical events, demogra-

phic data, and physician assessment of

global status. One of the authors (YY)

includes a physician note on a 1-page

2-sided form.

One example is illustrated in Figures 1

and 2. One side of the page (Fig. 1)

includes 10 activities of daily living, 3

items to assess psychological distress,

S-21

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

Fig. 1. (next page) A version of the multi-

dimensional health assessment questionnaire

(MDHAQ) designed for use in standard medical

care, which includes scores for physical func-

tion, psychological distress, pain, morning stiff-

ness, global status, self-report functional class,

change in status, fatigue, and disease activity

from the rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in-

dex (RADAI) self-report joint count, on one side

of one page. Scoring templates and space to enter

scores are provided on the questionnaire, as dis-

cussed in the text (translated versions of M D-

HAQ are available in French, German, Italian, Spa-

nish, Danish and Finnish at www. M D H A Q . o rg ) .

S-22

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

S-23

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

S-24

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

visual analog scales (VAS) for pain,

global status, and fatigue, and scores

for change in status and morning stiff-

ness, and on the other side (Fig. 2) a

review of systems, the rheumatoid arth-

ritis disease activity index (RADAI)

self-report joint count (28), recent med-

ical events, and demographic data.

Simple questionnaires such as a 10-

item HAQ II (5, 29) or 12-item ROAD

(30), present reasonable alternatives to

the MDHAQ. Differences in the patient

questionnaire appear acceptable, so

long as the critical “constant” region is

included.

It should be emphasized that there is no

need to involve a computer in any of

these scoring activities, which are easi-

ly accomplished using pencil and paper

in any clinical setting, although a com-

puter database may be desirable. The

acquisition of additional information

on one page concerning psychological

distress, fatigue, morning stiffness, and

change in status, and ease of scoring

may be the advantages of an MDHAQ

compared to the HAQ. A change in

scores for pain, fatigue, global status,

and psychological distress often is at

least as important in clinical care as a

change in the functional disability

score.

Patient questionnaires for clinical

research and for standard clinical

care

As noted, the primary purpose of mod-

ifying the HAQ to develop the MD-

HAQ was to facilitate the application

of patient questionnaires beyond clini-

cal research (31-33) to standard clinical

rheumatology care. Many reasons have

been cited to explain why patient ques-

tionnaires are not included in standard

care. The first may be that data from a

physician and/or high-technology im-

aging and laboratory source are regard-

ed as “objective” clinical information

in the traditional “biomedical model”

paradigm, the basis for most of the spec-

tacular advances in 20

th

century med-

icine. By contrast, data from a patient

are regarded as “subjective” – with the

primary purpose of leading to “objec-

tive,” definitive data. However, no stu-

dy has documented greater significance

for an imaging method or laboratory

test compared to a patient question-

naire in the prognosis or documenta-

tion of important clinical outcomes in

rheumatoid arthritis, such as functional

status (6, 7), work disability (8-10),

costs (11), joint replacement surg e r y

Table II. Three types of components of MDHAQ for standard clinical care: “Constant” -

required, and “variable” - strongly encouraged and optional.

“Constant”- Required “Variable”- Strongly Encouraged Variable – “Optional”

Physical function Psychological distress Review of systems

Pain Fatigue Medications used

Patient global Change in status Recent medical events

Morning stiffness Physician global

RADAI-self-report joint count Physician note on 2-page form

Table III.Patient questionnaires in clinical research and clinical care.

Feature Clinical research Clinical care

Design considerations Complete, long Patient friendly, can be completed

by patient within 5–10 min

Effect on patient visit Adds time, interferes with flow Saves time for MD and patient

Type of questionnaire May be “generic”, “disease specific”, Applicable to patients with all

other research goals rheumatic diseases

Scoring Complex, requires computer Simple, may “eyeball” results; scored

in < 20 seconds

Goal of data Add to research database Add to clinical care

Focus of analysis Groups of patients in clinical trials Individual patients cared for by

or observational databases individual physicians

Data management Send to data center Review for patient care; may enter

into flow-sheet to compare to previous

visits

Major criteria for use Validity, reliability; assess minimum Document status, medical and

clinically important significant medico-legal rationale for aggressive

difference (MCID) therapies

Disposition of Enter into computer Enter into flow sheet in medical

questionnaire record

Table IV. A practical system for routine assessment of functional status, pain, global status,

fatigue and psychological distress.

1. Patient is given 2-page questionnaire by receptionist; it generally is most feasible to include each

patient with each diagnosis at each visit in the infrastructure of clinical care.

2. Patient completes simple questionnaire with minimum interruption of patient flow, usually in

waiting room; help is needed by 5-25% of patients.

3. Nurse or staff member may help patients when needed, review questionnaire for completeness,

and may score questionnaire.

4. Physician does as little as possible, but should scan (“eyeball”) contents - may score question-

naire and/or perform formal joint count.

5. Office staff may enter data unto flow sheet with laboratory and medication data.

Fig. 2. ( p revious page) Reverse side of the

MDHAQ, which includes a review of systems,

the rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index

(RADAI) self-report joint count (28), recent

medical events, and demographic data.

S-25

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

Fig. 3.A patient seen initially on 5 March 2003, who developed rheumatoid arthritis in a post-partum period with a 3-month old baby, who she could not care

for because of functional disability. All MCP, PIPjoints, wrists and knees were tender and swollen. Her initial scores on 5 March 2003 were 6.3 for function-

al distress, 7.8 for pain, and 9.1 for global status. She was initially begun on prednisone 10 mg/day and methotrexate 15 mg/week. One week later she showed

substantial improvement with her functional status score declining to 2.0, pain to 5.6, and global status to 5.6. However, it was apparent that she had very

aggressive disease, and was begun on etanercept. Over the next 8 months clinical improvement is documented, with declines in the patient’s scores for func-

tional status to 0.67, pain to 0.7, global status to 0.3, as well as other scores. Two years later she continues in near-remission status, albeit with low dose

methotrexate, low-dose prednisone, and etanercept.

(12) or death (6, 13-19). If a laboratory

test for, say, a T-cell marker or cytokine

were available with the robust value of

the HAQ or MHAQ in the prognosis

and monitoring of rheumatoid arthritis,

it would surely be incorporated into

standard rheumatology care by all

rheumatologists.

One important concern that has not re-

ceived much emphasis involves the dif-

ferences between questionnaires de-

signed for clinical research versus

those intended for clinical care (Table

III). The experience of most rheumatol-

ogists with patient questionnaires has

involved lengthy questionnaires in cli-

nical trials and other clinical research,

and many rheumatologists have limited

experience with short questionnaires

adapted for standard clinical care. A

patient questionnaire designed for stan-

dard clinical care may differ consider-

ably from one designed for clinical re-

search (Table III), much as a test for

rheumatoid factor or C-reactive protein

developed in a research laboratory may

be adapted in a simplified form for

standard care.

In clinical research, the primary goal is

to acquire data that is as complete as

might be needed to address the study

questions. Patients and clinicians there-

fore recognize and accept the inconve-

niences of lengthy questionnaires. The

scoring may be quite complex and the

data are not interpreted at the clinical

site; rather they are sent to a data center

for entry into a large common database

(Table III). The clinician does not re-

view the data; indeed, in clinical trials

the clinician is generally expected not

to review the questionnaire data at all.

By contrast, a questionnaire for stan-

dard care must be feasible and practical

( Table III). Requirements for such a

questionnaire include (Table IV) that it

can be completed by a patient within 5-

10 minutes, scanned (“eyeballed”) by a

health professional for a clinical over-

view in less than 5 seconds, and scored

by a health professional within 20-30

seconds, and is amenable to entry onto

a flow sheet to compare with previous

visits within 30 seconds. Further, a

questionnaire for standard patient care

must be clinically applicable to patients

with all diagnoses (24, 34), and provide

time-saving information to the physi-

cian by enhancing a patient’s capacity

to describe concerns in the limited time

allotted for a clinical encounter. The

MDHAQ meets these requirements.

Use of patient questionnaires in

standard care

A very simple system has been imple-

mented effectively over the last 20

years, which can assure completion of

a questionnaire by almost every patient

at every visit (35) (Table IV). When the

patient registers for the visit, the recep-

tionist asks him or her to complete a

questionnaire – provided on a clip-

board together with a soft pencil or felt-

tip pen – while waiting to see the physi-

cian. The questionnaire should be pre-

sented as an important component of

medical care, contributing to provide

data regarding functional status, pain,

global status, fatigue, and psychologi-

cal status that cannot be obtained in any

other way. A cheerful and enthusiastic

manner is important – the patient loses

interest if the staff projects a general

disdain of questionnaires.

The questionnaire is completed by the

patient before being called into an ex-

amining room. Most patients wait at

least 5-10 minutes before seeing a rheu-

matologist. The questionnaire helps the

patient to focus on problems and sum-

marize the overall evaluation. Most pa-

tients do not need help from a health

care professional, although about 20%

of patients to ask for help from a fami-

ly member or health professional to

complete the questionnaire, which is

willingly provided.

The questionnaire may be reviewed

with a nurse or another member of the

office staff, when the weight or blood

pressure are checked, or when the pa-

tient is placed in an examination room.

This review is not necessary, but may

include the identification and comple-

tion of missing data, medications, pa-

tient inquiries, and scoring of the ques-

tionnaire scales, as described below.

The questionnaire should be scanned

briefly by the physician to review the

patient’s clinical status. Patients have

commented that they have felt unhappy

after completing questionnaires in phy-

sician’s offices if there was no evidence

that the information was reviewed by a

health professional.

Scoring of the MDHAQ

Another relatively neglected matter

involves the scoring of patient ques-

t i o n naires in standard clinical care. Of

course, it is possible to recognize the

extent of functional disability and pain

without a need for formal scoring, just

as a physician can recognize a fever or

tachycardia without formally measur-

ing the patient’s temperature or pulse.

H o w e v e r, formal quantitative informa-

tion enhances the information needed

for care, and formal scores for physical

function, pain and global status may

also improve care.

The MDHAQ has scoring templates

that allow a health professional to for-

merly depict a quantitative number for

each scale within 15 seconds, directly

on the questionnaire. The 10 activities

of daily living can be quickly totaled

without a calculator, computer or any

other device (other than a human

brain); the total is divided by 10 to

reach a 0–3 score, with scores compa-

rable to the HAQ. One can also divide

the score by 3 to derive a 0–10 score,

which will then be similar to scores for

pain and global status. Also included is

a logarithmic scale, which has been

found to be more sensitive than an

arithmetic scale to distinguish active

from control treatment in certain clini-

cal trials (Koch and Pincus, unpub-

lished data).

The visual analog scales for pain and

global status as well as fatigue, are pre-

sented as 21 circles rather than the tra-

ditional 10 cm line, to facilitate scoring

without a ruler. One version of the MD-

HAQ includes an arithmetic scale of

0–10 below the circles, and a logarith-

mic scale above the circles – the rheu-

matologist may choose either format.

The logarithmic scale has a range of 0-

3 for physical function, 0-3 for pain

and 0-4 for global status, for a total

range of 0-10. This score has been

termed the “rheumatology assessment

patient index data” (RAPID), and rep-

resents an index of patient scores with a

range of 0-10 that provides an absolute

score which is as sensitive as the dis-

ease activity score (DAS) in distin-

S-26

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

S-27

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

guishing active from control treatment

in certain clinical trials (Koch and Pin-

cus, unpublished data). Although the

format of labeling each circle may

appear quite “busy,” the inclusion of

only a few numbers along the visual

analog scale tends to lead patients to

cluster responses primarily in labeled

circles. Therefore, it appears best to la-

bel each circle or none at all, although

if there are no labels more time is

required to score the scales. Formal

scores can be entered into flowsheets as

illustrated below.

Management of MDHAQ data

using a clinical flowsheet

Many options exist for the management

of questionnaire data, ranging f r o m

simply scanning (“eyeballing”) the

questionnaire to assess patient status, to

formally scoring it, to keeping a flow-

sheet (Table IV, Fig. 3). A flowsheet

may be used to facilitate the recogni-

tion of possible changes in functional

capacity, pain, fatigue, or psychologi-

cal status from previous visits. A flow-

sheet appears very useful in the man-

agement of chronic disease in general,

and many clinicians record medica-

tions, laboratory tests, joint examina-

tion findings, and other data on a flow-

sheet. The one-page flowsheet, which

includes patient questionnaire scores,

laboratory data and drugs, is very use-

ful in standard clinical care.

One example of use of the flowsheet is

presented in Figure 3. This illustrates a

patient who was seen initially on 5

March 2003, who developed rheuma-

toid arthritis in a postpartum period

with a 3-month old baby, which she

could not take care of because of her

functional disability. All MCP, PIP

j o i n t s , wrists and knees were tender and

swollen. Her initial scores on 5 March

2003, were 6.3 for functional distress

7.8 for pain, and 9.1 for global status.

She was initially begun on prednisone

10 mg/day and methotrexate 15 mg/

week. One week later she showed sub-

stantial improvement with her func-

tional status score declining to 2.0, pain

to 5.6, and global status to 5.6. Howev-

er, it was apparent that she had very

aggressive disease, and was begun on

etanercept. Over the next 8 months, her

clinical improvement is documented

with declines of her scores for func-

tional status to 0.67, pain to 0.7, and

global status to 0.3, as well as other

scores. Two years later she continues in

n e a r-remission status, continuing to

take low-dose methotrexate, low-dose

prednisone, and etanercept.

Some principles of questionnaire

use in standard care

Clinicians have expressed concerns

that questionnaires may interfere with

office routine and time management,

with consequent increased costs and

time. However, data from a brief ques-

tionnaire designed for standard care

can provide an important s a v i n g o f

time (after a brief “learning curve,” as

is required with any new activity). In-

formation concerning functional status,

pain, psychological distress, fatigue,

global status, review of systems, and

medications are then known to the phy-

sician at the start of the visit, rather than

when acquiring basic data from the

patient. This facilitates a focus on mat-

ters that require attention, leading to

more efficient and effective clinical care.

The questionnaire contributes to clini-

cal judgement, but all decisions must

be made by the clinician.

Many specialized questionnaires such

as the Short Form 36 (SF36) and dis-

ease-specific questionnaires for anky-

losing spondylitis (36), fibromyalgia

(37) and osteoarthritis (38), are avail-

able for different types of clinical re-

search studies in which their use is un-

questioned. However, it is generally

not feasible to use additional question-

naires in standard clinical care. T h e

MDHAQ can be useful for patients

with any rheumatic disease (24, 34), all

of whom may experience physical dis-

ability, pain, fatigue and psychological

distress.

Many clinicians have suggested that it

would be desirable to select patients to

complete questionnaires on the basis of

specific diagnoses, the interval since

the last questionnaire, the beginning of

new therapy etc. However, schemes

that include only certain patients gener-

ally fail in standard clinical practice. It

is considerably easier for the off i c e

staff to hand a questionnaire to each

patient at each visit. Collection of rou-

tine data from consecutive patients at

each visit may be supplemented by

additional data collection at intervals in

certain subsets of patients, if desired.

For example, all patients of one of the

authors (TP) are invited to complete

questionnaires every 6 months for the

US National Database organized by Dr.

Wolfe (39).

Concluding thoughts

The authors believe that rheumatolo-

gists enhance the lives of their patients

as much as any physician, but improve-

ments in status generally are not docu-

mented quantitatively. The absence of

effective documentation adds a signifi-

cant problem to people with rheumatic

diseases, as the provision of many ser-

vices are limited in the current climate

of cost containment. Documentation of

the effectiveness of rheumatology care

is accomplished most cost-effectively

through the routine distribution of

patient self-report questionnaires in

standard care (35).

There is a general viewpoint that “sci-

ence” involves only high technology

and laboratory activities. However,

research over the last 25 years has doc-

umented that clinical rheumatology can

be a most effective quantitative “sci-

ence.” A self-report questionnaire may

be the only measure to recognize sig-

nificant disease progression over 5-10

years, while joint tenderness, erythro-

cyte sedimentation rate (ESR), global

severity, and morning stiffness may be

unchanged or improved over 5-10 years

(40). These observations suggest that

self-report questionnaires (and radio-

graphs) may be the optimal clinical

measures through which rheumatolo-

gists might document improvement or

prevention of disease progression over

5-10 years.

When data are not collected on any giv-

en day, information is not available to

compare to previous and future visits

or to document the potential value of

patient care. It may be regarded as an

intellectual responsibility of rheuma-

tology health professionals to imple-

ment clinical rheumatology as a quanti-

tative science, which is best accom-

plished using patient questionnaires.

S-28

Development of the MDHAQ / T. Pincus et al.

This practice will help to advance

rheumatology as a specialty to improve

the lives of millions of people with

rheumatic diseases.

References

1. FRIES JF, SPITZ P, KRAINES RG, HOLMAN

H R : Measurement of patient outcome in

arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980; 23: 137-45.

2. PINCUS T, SOKKA T, KAUTIAINEN H: Fur-

ther development of a physical function scale

on a multidimensional health assessment

questionnaire for standard care of patients

with rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol 2005;

32: 1432-9.

3. BRUCE B, FRIES JF: The Health Assessment

Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol

2005; 23 (Suppl. 39): S14-S18.

4. PINCUS T, SUMMEY JA, SORACI SA, JR. ,

WALLSTON KA, HUMMON NP: Assessment

of patient satisfaction in activities of daily

living using a modified Stanford health as-

sessment questionnaire. A rthritis Rheum

1983; 26: 1346-53.

5. WOLFE F, MICHAUD K, PINCUS T: Develop-

ment and validation of the health assessment

questionnaire II: A revised version of the

health assessment questionnaire. A rt h r i t i s

Rheum 2004; 50: 3296-305.

6. PINCUS T, CALLAHAN LF, SALE W G ,

BROOKS AL, PAYNE LE, VAUGHN W K :

Severe functional declines, work disability,

and increased mortality in seventy-five rheu-

matoid arthritis patients studied over nine

years. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 27: 864-72.

7. WOLFE F, CATHEY MA: The assessment and

prediction of functional disability in rheuma-

toid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1991; 18: 1298-

306.

8. C A L L A H A N L F, BLOCH DA, PINCUS T:

Identification of work disability in rheuma-

toid arthritis: Physical, radiographic and lab-

oratory variables do not add explanatory

power to demographic and functional vari-

ables. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45: 127-38.

9. WOLFE F, HAWLEY DJ: The longterm out-

comes of rheumatoid arthritis: Work disabili-

ty: A prospective 18 year study of 823 pa-

tients. J Rheumatol 1998; 25: 2108-17.

10. S O K K A T, KAUTIAINEN H, MÖTTÖNEN T,

HANNONEN P:Work disability in rheumatoid

arthritis 10 years after the diagnosis. J

Rheumatol 1999; 26: 1681-5.

11. LUBECK DP, SPITZ PW, FRIES JF, WOLFE F,

MITCHELLDM, ROTH SH:A multicenter stu-

dy of annual health service utilization and

costs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum

1986; 29: 488-93.

12. W O L F E F, ZWILLICH S H: The long-term

outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis: A 23-year

prospective, longitudinal study of total joint

replacement and its predictors in 1,600 pa-

tients with rheumatoid arthritis. A rt h r i t i s

Rheum 1998; 41: 1072-82.

13. WOLFE F, KLEINHEKSEL SM, CATHEY MA,

HAWLEY DJ, SPITZ PW, FRIES JF: The clini-

cal value of the Stanford health assessment

questionnaire functional disability index in

patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheuma -

tol 1988; 15: 1480-8.

14. LEIGH JP, FRIES JF: Mortality predictors

among 263 patients with rheumatoid arthri-

tis. J Rheumatol 1991; 18: 1307-12.

15. P I N C U S T, BROOKS RH, CALLAHAN LF:

Prediction of long-term mortality in patients

with rheumatoid arthritis according to simple

questionnaire and joint count measures. Ann

Intern Med 1994; 120: 26-34.

16. CALLAHAN LF, CORDRAY DS, WELLS G,

PINCUS T: Formal education and five-year

mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: Mediation

by helplessness scale scores. Arthritis Care

Res 1996; 9: 463-72.

17. CALLAHAN LF, PINCUS T, HUSTON JW, III,

BROOKS RH, NANCE EP, JR, KAYE JJ: Mea-

sures of activity and damage in rheumatoid

arthritis: Depiction of changes and prediction

of mortality over five years. Arthritis Care

Res 1997; 10: 381-94.

18. SÖDERLIN MK, NIEMINEN P, HAKALA M:

Functional status predicts mortality in a com-

munity based rheumatoid arthritis popula-

tion. J Rheumatol 1998; 25:1895-9.

19. S O K K A T, HAKKINEN A, KRISHNAN E,

HANNONEN P: Similar prediction of mortal-

ity by the health assessment questionnaire in

patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the

general population. Ann Rheum Dis 2 0 0 4 ;

63: 494-7.

20. WOLFE F: A brief health status instrument:

CLINHAQ. Arthritis Rheum 1989; 32: S99

(abstract).

21. PINCUS T, CALLAHAN LF, BROOKS RH,

FUCHS HA, OLSEN NJ, KAYE JJ: Self-report

questionnaire scores in rheumatoid arthritis

compared with traditional physical, radio-

graphic, and laboratory measures. Ann Intern

Med 1989; 110: 259-66.

22. STRAND V, COHEN S, SCHIFF M et al.: Treat-

ment of active rheumatoid arthritis with lef-

lunomide compared with placebo and meth-

otrexate. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 2542-

50.

23. F E L S O N D T, A N D E R S O N JJ, BOERS M e t

al.: The American College of Rheumatology

preliminary core set of disease activity mea-

sures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials.

Arthritis Rheum 1993; 36: 729-40.

24. PINCUS T, SWEARINGEN C, WOLFE F: To-

ward a multidimensional health assessment

questionnaire (MDHAQ): Assessment of

advanced activities of daily living and psy-

chological status in the patient friendly health

assessment questionnaire format. A rt h r i t i s

Rheum 1999; 42: 2220-30.

25. PINCUS T, SOKKA T, KAUTIAINEN H: Pa-

tients seen for standard rheumatoid arthritis

care have significantly better articular, radio-

graphic, laboratory, and functional status in

2000 than in 1985. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52:

1009-19.

26. BOERS M, TUGWELL P, FELSON DT et al.:

World Health Organization and International

League of Associations for Rheumatology

core endpoints for symptom modifying anti-

rheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis clini-

cal trials. J Rheumatol 1994; 21 (Suppl. 41):

86-9.

27. TUGWELL P, BOERS M: OMERACT Com-

mittee. Proceedings of the OMERACT Con-

ferences on outcome measures in rheumatoid

arthritis clinical trials, Maastrict, Nether-

lands. J Rheumatol 1993; 20: 527-91.

28. STUCKI G, LIANG MH, STUCKI S, BRÜHL-

MANN P, MICHEL B A: A s e l f - a d m i n i s t e r e d

rheumatoid arthritis disease activity index

(RADAI) for epidemiologic research. Arthri -

tis Rheum 1995; 38: 795-8.

29. WOLFE F: Why the HAQ-II can be an effec-

tive substitute for the HAQ. Clin Exp

Rheumatol 2005; 23 (Suppl. 39): S29-S30.

30. S A L A F F I F, STA N C AT I A, NERI R, GRASSI

W, BOMBARDIERI S: Measuring functional

disablity in early rheumatoid arthritis: the

validity, reliability and responsiveness of the

Recent Onset Arthritis Disablity (ROAD)

Index. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23 (Suppl.

39): S31-S42.

31. PINCUS T: Documenting quality manage-

ment in rheumatic disease: Are patient ques-

tionnaires the best (and only) method? Arth -

ritis Care Res 1996; 9: 339-48.

32. WOLFE F, PINCUS T: Listening to the patient:

A practical guide to self-report question-

naires in clinical care. Arthritis Rheum 1999;

42: 1797-808.

33. PINCUS T, WOLFE F: An infrastructure of

patient questionnaires at each rheumatology

visit: Improving efficiency and documenting

care. J Rheumatol 2000; 27: 2727-30.

34. CALLAHAN LF, SMITH WJ, PINCUS T: Self-

report questionnaires in five rheumatic dis-

eases: Comparisons of health status con-

structs and associations with formal educa-

tion level. A rthritis Care Res 1989; 2: 122-31.

35. WOLFE F, PINCUS T: Data collection in the

clinic. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1995; 21:

321-58.

36. ZOCHLING J, BRAUN J: Assessment of an-

kylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol

2005; 23 (Suppl. 39): S133-S141.

37. B E N N E T T R: The Fibromyalgia Impact Ques-

tionnaire (FIQ): A reviw of its development,

current version, operating characteristics and

uses. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23 (Suppl.

39): S152-S162.

38. BELLAMY N: The WOMAC Knee and Hip

Osteoarthritis Indices: Development, valida-

tion, globalization and influence on the dev-

elopment of the AUSCAN Hand Osteoarthri-

tis Indices. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23

(Suppl. 39): S148-S153.

39. WOLFE F:A brief introduction to the Nation-

al Data Bank for Rheumatic Diseases. Clin

Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23 (Suppl. 39): S168-

S171.

40. H AW L E Y DJ, W O L F E F: Sensitivity to

change of the Health Assessment Question-

naire (HAQ) and other clinical and health

status measures in rheumatoid arthritis: re-

sults of short term clinical trials and observa-

tional studies versus long term observational

studies. Arthritis Care Res 1992; 5: 130-6.