Visit the National Academies Press online and register for...

Instant access to free PDF downloads of titles from the

Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press.

Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences.

Request reprint permission for this book

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

10% off print titles

Custom notication of new releases in your eld of interest

Special offers and discounts

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF ENGINEERING

INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL

This PDF is available from The National Academies Press at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13363

ISBN

978-0-309-25416-8

144 pages

6 x 9

PAPERBACK (2012)

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Daniel S. Nagin and John V. Pepper, editors; Committee on Deterrence

and the Death Penalty; Committee on Law and Justice; Division on

Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Research Council

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

DETERRENCE

AND THE

DEATH PENALT Y

Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Daniel S. Nagin and John V. Pepper, Editors

Committee on Law and Justice

Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS • 500 Fifth Street, NW • Washington, DC 20001

NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Govern-

ing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the

councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineer-

ing, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for

the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropri-

ate balance.

This study was supported by Grant Number 2010-IJ-CX-0018 from the National

Institute of Justice, Grant Number TRF09-01115 from the Tides Foundation, and

the Proteus Action League (grant not numbered). Any opinions, findings, conclu-

sions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or agencies that pro-

vided support for the project.

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-309-25416-8

International Standard Book Number-10: 0-309-25416-7

Additional copies of this report are available from the National Academies Press,

500 Fifth Street, NW, Keck 360, Washington, DC 20001; (800) 624-6242 or (202)

334-3313; http://www.nap.edu.

Copyright 2012 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

Suggested citation: National Research Council. (2012). Deterrence and the Death

Penalty. Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty, Daniel S. Nagin and John

V. Pepper, Eds. Committee on Law and Justice, Division of Behavioral and Social

Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

The National Academy of Sciences is a private, nonprofit, self-perpetuating society

of distinguished scholars engaged in scientific and engineering research, dedicated to

the furtherance of science and technology and to their use for the general welfare.

Upon the authority of the charter granted to it by the Congress in 1863, the Acad-

emy has a mandate that requires it to advise the federal government on scientific

and technical matters. Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone is president of the National Academy

of Sciences.

The National Academy of Engineering was established in 1964, under the charter

of the National Academy of Sciences, as a parallel organization of outstanding en-

gineers. It is autonomous in its administration and in the selection of its members,

sharing with the National Academy of Sciences the responsibility for advising the

federal government. The National Academy of Engineering also sponsors engineer-

ing programs aimed at meeting national needs, encourages education and research,

and recognizes the superior achievements of engineers. Dr. Charles M. Vest is presi-

dent of the National Academy of Engineering.

The Institute of Medicine was established in 1970 by the National Academy of

Sciences to secure the services of eminent members of appropriate professions in

the examination of policy matters pertaining to the health of the public. The Insti-

tute acts under the responsibility given to the National Academy of Sciences by its

congressional charter to be an adviser to the federal government and, upon its own

initiative, to identify issues of medical care, research, and education. Dr. Harvey V.

Fineberg is president of the Institute of Medicine.

The National Research Council was organized by the National Academy of Sci-

ences in 1916 to associate the broad community of science and technology with the

Academy’s purposes of furthering knowledge and advising the federal government.

Functioning in accordance with general policies determined by the Academy, the

Council has become the principal operating agency of both the National Academy

of Sciences and the National Academy of Engineering in providing services to

the government, the public, and the scientific and engineering communities. The

Council is administered jointly by both Academies and the Institute of Medicine.

Dr. Ralph J. Cicerone and Dr. Charles M. Vest are chair and vice chair, respectively,

of the National Research Council.

www.national-academies.org

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

v

COMMITTEE ON DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

DANIEL S. NAGIN (Chair), H. John Heinz III College, Carnegie Mellon

University

KERWIN K. CHARLES, Harris School of Public Policy Studies,

University of Chicago

PHILIP J. COOK, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University

STEVEN N. DURLAUF, Department of Economics, University of

Wisconsin–Madison

AMELIA M. HAVILAND, H. John Heinz III College, Carnegie Mellon

University

GERARD E. LYNCH, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

CHARLES F. MANSKI, Department of Economics, Northwestern

University

JAMES Q. WILSON, School of Public Policy, Pepperdine University, and

Clough Center for the Study of Constitutional Democracy, Boston

College

JANE L. ROSS, Study Director

JOHN V. PEPPER, Consultant

KEIKO ONO, Senior Program Associate

CAROL HAYES, Christine Mirzayan Fellow

BARBARA BOYD, Administrative Associate

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

vi

COMMITTEE ON LAW AND JUSTICE

2012

JEREMY TRAVIS (Chair), John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City

University of New York

CARL C. BELL, Community Mental Health Council, Inc., Chicago, IL

JOHN J. DONOHUE, III, Stanford Law School, Stanford University

MARK A.R. KLEIMAN, Department of Public Policy, University of

California, Los Angeles

GARY LAFREE, Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice,

University of Maryland

JANET L. LAURITSEN, Department of Criminology and Criminal

Justice, University of Missouri-St. Louis

GLENN C. LOURY, Department of Economics, Brown University

CHARLES F. MANSKI, Department of Economics, Northwestern

University

TERRIE E. MOFFITT, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience,

Duke University

DANIEL S. NAGIN, H. John Heinz III College, Carnegie Mellon

University

RUTH D. PETERSON, Criminal Justice Research Center, Ohio State

University

ANNE MORRISON PIEHL, Department of Economics and Program in

Criminal Justice, Rutgers University

DANIEL B. PRIETO, Public Sector Strategy & Innovation, IBM Global

Business Services, Washington, DC

ROBERT J. SAMPSON, Department of Sociology, Harvard University

DAVID WEISBURD, Department of Criminology, Law and Society,

George Mason University

CATHY SPATZ WIDOM, Psychology Department, John Jay College of

Criminal Justice, City University of New York

PAUL K. WORMELI, Integrated Justice Information Systems,

Ashburn, VA

JANE L. ROSS, Director

BARBARA BOYD, Administrative Associate

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

vii

IN MEMORIAM

James Q. Wilson

1931-2012

“I’ve tried to follow the facts wherever they land.”

This report is dedicated to James Q. Wilson for

his long service to the National Research Council,

his influential career of scholarship and public

service, and his unblinking commitment to the

principle that science requires us to interpret

the evidence as it is, not as we want it to be.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

ix

Preface

M

ore than three decades ago, in Deterrence and Incapacitation:

Estimating the Effects of Criminal Sanctions on Crime Rates,

the National Research Council (NRC) (1978, p. 9) concluded

that “available studies provide no useful evidence on the deterrent effect

of capital punishment.” That report was issued 2 years after the Supreme

Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia ended a 4-year moratorium on execu-

tion in the United States. In the 35 years since the publication of that report,

especially in recent years, a considerable number of post-Gregg studies have

attempted to estimate the effect of the legal status or the actual implemen-

tation of the death penalty on homicide rates. Those studies have reached

widely varying conclusions.

Against this background, the NRC formed the Committee on Deter-

rence and the Death Penalty to address whether the available evidence

provides a reasonable basis for drawing conclusions about the magnitude of

the effect of capital punishment on homicide rates. At a workshop on April

28-29, 2011, workshop papers commissioned by the committee (which will

be published in a special issue of the Journal of Quantitative Criminology)

were presented and discussed by their authors: Robert J. Apel, University at

Albany, State University of New York; Aaron Chalfin, University of Califor-

nia, Berkeley; Chao Fu, University of Wisconsin–Madison; Justin McCrary,

University of California, Berkeley; Salvador Navarro, University of Western

Ontario, Ontario, Canada; John V. Pepper, University of Virginia; and

Steven Raphael, University of California, Berkeley. The workshop also

included comments on the presentations by Jeffrey Grogger, University

of Chicago; Guido Imbens, Harvard University; Kenneth C. Land, Duke

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

x PREFACE

University; Christopher Sims, Princeton University; and Justin Wolfers,

University of Pennsylvania.

The committee appreciates the contributions of these presenters and

those who commented on them to the development of its report. In ad-

dition, John V. Pepper provided invaluable assistance to the committee

throughout its deliberations. The work of staff members from the Com-

mittee on Law and Justice of the NRC facilitated the committee’s work in

many ways. Thanks are due to Jane L. Ross, study director; Keiko Ono,

senior program associate; Carol Hayes, Christine Mirzayan fellow; and

Barbara Boyd, administrative coordinator.

Many individuals at the NRC assisted the committee. We thank Kirsten

Sampson-Snyder, who shepherded the report through the NRC review pro-

cess, Eugenia Grohman, who edited the draft report, and Yvonne Wise, for

processing the report through final production.

This report has been reviewed in draft form by individuals chosen for

their diverse perspectives and technical expertise, in accordance with pro-

cedures approved by the NRC’s Report Review Committee. The purpose

of this independent review is to provide candid and critical comments that

will assist the institution in making its published report as sound as possible

and to ensure that the report meets institutional standards for objectivity,

evidence, and responsiveness to the study charge. The review comments

and draft manuscript remain confidential to protect the integrity of the

deliberative process. We thank the following individuals for their review of

this report: John Donohue, III, Stanford Law School, Stanford University;

Andrew Gelman, Department of Statistics and Department of Political Sci-

ence, Columbia University; Kenneth C. Land, Department of Sociology,

Duke University; Candice Odgers, School of Social Ecology, University of

California, Irvine; Ricardo Reis, Department of Economics, Columbia Uni-

versity; Greg Ridgeway, RAND Safety and Justice Program, RAND Center

on Quality Policing, RAND Corporation; Robert J. Sampson, Department

of Sociology, Harvard University; Dick Thornburgh, Counsel, K&L Gates,

LLP, and former Attorney General of the United States; Petra E. Todd,

Department of Economics, University of Pennsylvania; and Michael Tonry,

School of Law, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Although the reviewers listed above have provided many constructive

comments and suggestions, they were not asked to endorse the conclusions

or recommendations nor did they see the final draft of the report before its

release. The review of this report was overseen by Gary LaFree, National

Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, Univer-

sity of Maryland, and John T. Monahan, University of Virginia Law School.

Appointed by the NRC, they were responsible for making certain that an

independent examination of this report was carried out in accordance with

institutional procedures and that all review comments were carefully con-

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

PREFACE xi

sidered. Responsibility for the final content of this report rests entirely with

the authoring committee and the institution.

This report is dedicated to James Q. Wilson. Jim was a valued member

of this and many other NRC committees on which he served over his long

and influential career. Jim’s contributions to scholarship and public service

will stand as enduring testimony to the power of his intellect. He was a

quiet but forceful proponent for balanced and clear-minded assessment of

the evidence. I first met Jim in my role as a staff member of the 1978 NRC

committee that resulted in report Deterrence and Incapacitation: Estimat-

ing the Effect of Criminal Sanctions on Crime Rates. I was deeply impressed

by the clarity of his thought and gift for communication. He served as a

role model for me ever since. I was thus especially honored that he agreed

to serve on this committee, which was greatly aided by his constructive

participation throughout our deliberations.

Daniel S. Nagin, Chair

Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

xiii

Contents

SUMMARY 1

Shortcomings in Existing Research, 4

Specification of the Sanction Regime for Homicide, 4

Potential Murderers’ Perceptions of and Responses to

Capital Punishment, 5

Strong and Unverifiable Assumptions, 6

Next Steps for Research, 7

References, 8

1 INTRODUCTION 9

The Current Debate, 9

Committee Charge and Scope of Work, 11

References, 14

2 CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE POST-GREGG ERA 15

Executions and Death Sentences Over Time, 15

Use of the Death Penalty, 20

References, 26

3 DETERMINING THE DETERRENT EFFECT OF

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: KEY ISSUES 27

Concepts of Deterrence, 28

Sanction Regimes, 32

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

xiv CONTENTS

Data Issues, 36

Variations in Murder Rates, 37

Reciprocal Effects Between Homicide Rates and

Sanction Regimes, 41

Summary, 43

References, 44

4 PANEL STUDIES 47

Panel Studies Reviewed, 48

Methods Used: Overview, 48

The Studies, Their Characteristics, and the Effects Found, 49

Specifying the Expected Cost of Committing a Capital

Homicide: f(Z

it

), 54

Model Assumptions, 63

Benefits of Random Assignment, 64

Fixed Effect Regression Model, 65

Instrumental Variables, 66

Homogeneity, 68

Conclusion, 70

References, 71

5 TIME-SERIES STUDIES 75

Basic Conceptual Issues, 76

Execution Event Studies, 76

Studies of Deviations from Fitted Trends, 78

Vector Autoregressions, 82

Evidence Under Existing Criminal Sanction Regimes, 82

Granger Causality and Causality as Treatment Response, 86

Choice of Variables in VAR Studies, 88

Inferences Under Alternative Sanction Regimes, 89

Event Studies, 90

Time-Series Regressions, 92

Cross-Polity Comparisons, 94

Conclusions, 97

References, 99

6 CHALLENGES TO IDENTIFYING DETERRENT EFFECTS 101

Data on Sanction Regimes, 104

Perceptions of Sanction Risks, 105

Measurement of Perceptions, 107

Inference on Perceptions from Homicide Rates Following

Executions, 110

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

CONTENTS xv

Identifying Effects: Feedbacks and Unobserved Confounders, 111

Feedback Effects, 111

Omitted Variables, 112

The Equilibrium Effect, 113

Addressing Model Uncertainty with Weaker Assumptions, 115

Model Averaging, 116

Partial Identification, 119

References, 121

Appendix: Biographical Sketches of Committee Members and Staff 125

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

1

Summary

I

n 1976, the Supreme Court decision in Gregg v. Georgia (428 U.S. 153)

ended the 4-year moratorium on executions that had resulted from its

1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia (408 U.S. 238). In the immediate

aftermath of Gregg, an earlier report of the National Research Council

(NRC) reviewed the evidence relating to the deterrent effect of the death

penalty that had been gathered through the mid-1970s. That review was

highly critical of the earlier research and concluded (National Research

Council, 1978, p. 9) that “available studies provide no useful evidence on

the deterrent effect of capital punishment.”

During the 35 years since Gregg, and particularly in the past decade,

many additional studies have renewed the attempt to estimate the effect of

capital punishment on homicide rates. Most researchers have used post-

Gregg data from the United States to examine the statistical association

between homicide rates and the legal status, the actual implementation of

the death penalty, or both. The studies have reached widely varying, even

contradictory, conclusions. Some studies conclude that executions save

large numbers of lives; others conclude that executions actually increase

homicides; and still others conclude that executions have no effect on

homicide rate. Commentary on the scientific validity of the findings has

sometimes been acrimonious. The Committee on Deterrence and the Death

Penalty was convened against this backdrop of conflicting claims about the

effect of capital punishment on homicide rates. The committee addressed

three main questions laid out in its charge:

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

2 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

1. Does the available evidence provide a reasonable basis for drawing

conclusions about the magnitude of capital punishment’s effect on

homicide rates?

2. Are there differences among the extant analyses that provide a ba-

sis for resolving the differences in findings? Are the differences in

findings due to inherent limitations in the data? Are there existing

statistical methods and/or theoretical perspectives that have yet to

be applied that can better address the deterrence question? Are the

limitations of existing evidence reflective of a lack of information

about the social, economic, and political underpinnings of homi-

cide rates and/or the administration of capital punishment that first

must be resolved before the deterrent effect of capital punishment

can be determined?

3. Do potential remedies to shortcomings in the evidence on the de-

terrent effect of capital punishment have broader applicability for

research on the deterrent effect of noncapital sanctions?

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION: The committee con-

cludes that research to date on the effect of capital punishment on ho-

micide is not informative about whether capital punishment decreases,

increases, or has no effect on homicide rates. Therefore, the committee

recommends that these studies not be used to inform deliberations

requiring judgments about the effect of the death penalty on homicide.

Consequently, claims that research demonstrates that capital punish-

ment decreases or increases the homicide rate by a specied amount

or has no effect on the homicide rate should not inuence policy judg-

ments about capital punishment.

The committee was disappointed to reach the conclusion that research

conducted in the 30 years since the earlier NRC report has not sufficiently

advanced knowledge to allow a conclusion, however qualified, about the ef-

fect of the death penalty on homicide rates. Yet this is our conclusion. Some

studies play the useful role, either intentionally or not, of demonstrating the

fragility of claims to have or not to have found deterrent effects. However,

even these studies suffer from two intrinsic shortcomings that severely limit

what can be learned from them about the effect of the death penalty—as it

has actually been administered in the United States in the past 35 years—on

the death penalty.

Properly understood, the relevant question about the deterrent effect of

capital punishment is the differential or marginal deterrent effect of execu-

tion over the deterrent effect of other available or commonly used penalties,

specifically, a lengthy prison sentence or one of life without the possibility of

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

SUMMARY 3

parole. One major deficiency in all the existing studies is that none specify

the noncapital sanction components of the sanction regime for the punish-

ment of homicide. Another major deficiency is the use of incomplete or

implausible models of potential murderers’ perceptions of and response to

the capital punishment component of a sanction regime. Without this basic

information, it is impossible to draw credible findings about the effect of

the death penalty on homicide.

Commentary on research findings often pits studies claiming to find

statistically significant deterrent effects against those finding no statistically

significant effects, with the latter studies sometimes interpreted as imply-

ing that there is no deterrent effect. A fundamental point of logic about

hypothesis testing is that failure to reject a null hypothesis does not imply

that the null hypothesis is correct.

Our mandate was not to assess whether competing hypotheses about

the existence of marginal deterrence from capital punishment are plausible,

but simply to assess whether the empirical studies that we have reviewed

provide scientifically valid evidence. In its deliberations and in this report,

the committee has made a concerted effort not to approach this question

with a prior assumption about deterrence. Having reviewed the research

that purports to provide useful evidence for or against the hypothesis that

the death penalty affects homicide rates, we conclude that it does not pro-

vide such evidence.

A lack of evidence is not evidence for or against the hypothesis. Hence,

the committee does not construe its conclusion that the existing studies are

uninformative as favoring one side or the other side in the long-standing

debate about deterrence and the death penalty. The committee also empha-

sizes that deterrence is but one of many considerations relevant to rendering

a judgment on whether the death penalty is good public policy.

Even though the scholarly evidence on the deterrent effect of capital

punishment is too weak to guide decisions, this does not mean that people

should have no views on capital punishment. Judgment about whether

there is a deterrent effect is still relevant to policy, but that judgment

should not be justified based on evidence from existing research on capital

punishment’s effect on homicide. Just as important, the committee did not

investigate the moral arguments for or against capital punishment or the

empirical evidence on whether capital punishment is administered in a

nondiscriminatory and consistent fashion. Nor did it investigate whether

the risk of mistaken execution is acceptably small or how the cost of ad-

ministering the death penalty compares to other sanction alternatives. All

of these issues are relevant to making a judgment about whether the death

penalty is good public policy.

Our charge was also limited to assessing the evidence on the deterrent

effect of the death penalty on murder, not the deterrent effect of noncapital

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

4 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

sanctions on crime more generally. Our negative conclusion on the infor-

mativeness of the evidence on the former issue should not be construed as

extending to the latter issue because the committee did not review the very

large body of evidence on the deterrent effect of noncapital sanctions.

SHORTCOMINGS IN EXISTING RESEARCH

The post-Gregg studies are usefully divided into two categories based

on the type of data analyzed. One category, which we call panel data stud-

ies, analyzes sets of states or counties measured over time, usually from

about 1970 to 2000. These studies relate homicide rates to variations over

time and across states or counties in the legal status of capital punishment

and/or the frequency of executions. The second category, which we call

time-series studies, generally studies only a single geographic unit. The geo-

graphic unit may be as large as a nation or as small as a city. These studies

usually examine whether there are short-term changes in homicide rates in

that geographic unit in the aftermath of an execution.

As noted above, research on the effect of capital punishment on ho-

micide suffers from two fundamental flaws that make them uninformative

about the effect of capital punishment on homicide rates: they do not

specify the noncapital sanction components of the sanction regime for the

punishment of homicide, and they use incomplete or implausible models of

potential murderers’ perceptions of and response to the capital punishment

component of a sanction regime. In addition, the existing studies use strong

and unverifiable assumptions to identify the effects of capital punishment

on homicides.

Specication of the Sanction Regime for Homicide

The sanction regime for homicide comprises both the capital and non-

capital sanctioning options that are available for its punishment and the

policies governing the administration of these options. The relevant ques-

tion regarding the deterrent effect of capital punishment is the differential

deterrent effect of execution in comparison with the deterrent effect of other

available or commonly used penalties. We emphasize “differential” because

it is important to recognize that even in states that make the most intense

use of capital punishment, most convicted murderers are not sentenced to

death but to a lengthy prison sentence—often life without the possibility

of parole.

None of the studies that we reviewed (both those using a panel ap-

proach and those using time-series approaches) accounted for the severity

of noncapital sanctions in their analyses. As discussed in Chapters 4 and 6,

there are sound reasons to expect that the severity of the noncapital sanc-

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

SUMMARY 5

tions for homicide varies systematically with the availability of capital pun-

ishment, the intensity of use of capital punishment, or both. For example,

the political culture of a state may affect the frequency of the use of capital

punishment and also the severity of noncapital sanctions for homicide.

Thus, any effect that these noncapital sanctions have on the homicide rate

may contaminate any estimated effect of capital punishment.

Potential Murderers’ Perceptions of and Responses to Capital Punishment

A by-product of the absence of consideration of the noncapital com-

ponent of the sanction regime is that no studies consider how the capital

and noncapital components of a regime combine in affecting the behavior

of potential murderers. Only the capital component of the sanction regime

has been studied, and this in itself shows both a serious conceptual flaw

and a serious data flaw in the entire body of research.

Several factors make the attempts by the panel studies to specify the

capital component of state sanctions regimes uninterpretable. First, the

findings are very sensitive to the way the risk of execution is specified. Sec-

ond, there is no logical basis for resolving disagreements about how this

risk should be measured.

Much of the panel research simply assumes that potential murderers

respond to the objective risk of execution. There are significant complexities

in computing this risk even for a well-informed researcher, let alone for a

potential murderer. Among these complexities are that only 15 percent of

people who have been sentenced to death since 1976 have actually been

executed and a large fraction of death sentences are subsequently reversed.

None of the measures that are used in the research have been shown to be

a better measure of the risk of execution than any others. Thus, even if one

assumes that a potential murderer’s perceived risk corresponds to the actual

risk, there is no basis for arbitrating the competing claims about what is

the “right” risk measure.

The committee is also skeptical that potential murderers can possibly

estimate the objective risk, whatever it is. Hence, there is good reason to be-

lieve that perceived risk deviates from the objective risk. The research does

not address how potential murderers’ perceptions of capital punishment—

and, more generally, noncapital sanction risks—are formed.

The time-series studies come in many forms—studies of a single ex-

ecution event, studies of many events, and studies with a cross-polity

dimension—but a common feature of the studies is that none of them at-

tempts to specify even the capital component of the overall sanction regime.

This is a crucial shortcoming and is exemplified in the time-series analyses

that examine the association between deviations of number of executions

from a fitted trend line and deviations of homicides from a fitted trend line.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

6 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

For potential murderers to possibly be responsive to deviations from the

execution trend line, they have to be attentive to it. The studies are silent on

two key questions: (1) Why are potential murderers attentive to the trend

line in the number of executions? (2) Why do they respond to deviations

from the trend line?

If time-series analyses find that homicide rates are not responsive to

such deviations, it may be that potential murderers are responding to the

trend line in executions but not to deviations from it. For example, a ris-

ing trend in the number of executions might be perceived as signaling a

toughening of the sanction regime, which might deter potential murderers.

Alternatively, if a time-series analysis finds that homicide rates are respon-

sive to such deviations, the question is why? One possibility is that potential

murderers interpret the deviations as new information about the intensity

of the application of capital punishment—that is, they perceive a change

in the part of the sanction regime relating to application of capital punish-

ment. If so, a deviation from the execution trend line may cause potential

murderers to alter their perceptions of the future course of the trend line,

which in turn may change their behavior.

Yet, even accepting this idea, a basic question persists. Why should the

trend lines fit by researchers coincide with the perceptions of potential mur-

derers about trends in executions? Because there are no studies that include

empirical analyses on the question of how potential murderers perceive the

risk of sanctions, there is no basis for assuming that the trend line specified

by researchers corresponds to the trend line (if any) that is perceived by

potential murderers. If researchers and potential murderers do not perceive

trends the same way, then time-series analyses do not correctly identify

what potential murderers perceive as deviations. Because of this basic flaw

in the research, the committee has no basis for assessing whether the find-

ings of time-series studies reflect a real effect of executions on homicides

or are artifacts of models that incorrectly specify how deviations from a

trend line cause potential murderers to update their forecasts of the future

course of executions.

Strong and Unveriable Assumptions

To obtain a single estimate that specifies the effect of capital punish-

ment on homicide, researchers invariably rely on a range of strong and

unverified assumptions. In part (as discussed above), this reflects the lack of

basic information on the relevant sanction regimes for homicide and the as-

sociated perceptions of risk. None of the studies accounts for the noncapital

component of the sanction regime, and potential murderers’ risk percep-

tions are assumed to depend on observable frequencies of arrest, conviction,

and execution. The ad hoc choices of alternative models of risk perceptions

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

SUMMARY 7

lead to very different inferences on the effects of capital punishment, and

none of them is inherently any more justifiable than any other.

Additional data and research on sanction regimes and risk perceptions

may serve to reduce this form of model uncertainty. However, even if these

uncertainties are fully reconciled, a more fundamental problem is that the

outcomes of counterfactual sanction policies are unobservable. That is,

there is no way to determine what would have occurred if a given state

had a different sanction regime. In light of this observational problem, the

available data cannot reveal the effect of capital punishment itself since the

policy-relevant question is whether capital punishment deters homicides

relative to other sanction regimes. That is, the data alone cannot reveal

what the homicide rate in a state without (with) a capital punishment re-

gime would have been had the state (not) had such a regime.

The standard procedure in capital punishment research has been to

impose sufficiently strong assumptions to yield definitive findings on deter-

rence. For example, a common assumption is that sanctions are random

across states or years, as they would be if sanctions had been randomly as-

signed in an experiment. Another common assumption is that the response

of criminality to sanctions is homogeneous across states and years. Some

studies use instrumental variables to identify deterrent effects, but this

requires yet other assumptions. The use of strong assumptions hides the

problem that the study of deterrence is plagued by model uncertainty and

that many of the assumptions used in the research lack credibility.

NEXT STEPS FOR RESEARCH

The earlier NRC committee concluded that it was “skeptical that the

death penalty [as practiced in the United States] can ever be subjected to the

kind of statistical analysis that would validly establish the presence or ab-

sence of a deterrent effect” (National Research Council, 1978, p. 62). The

present committee is not so pessimistic and offers several recommendations

for addressing the shortcomings in research to date on capital punishment.

They include

1. collection of the data required for a more complete specification of

both the capital and noncapital components of the sanction regime

for murder;

2. research on how potential murderers perceive the sanction regime

for murder; and

3. use of methods that makes less strong and more credible assump-

tions to identify or bound the effect of capital punishment on

homicides.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

8 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

In addition, the committee suggests research on how the presence of capital

punishment in a sanctions regime affects the administration of the regime

and how the homicide rate affects the statutory definition of the sanction

regime and its administration.

The committee does not expect that advances in new data on sanction

regimes and obtaining knowledge of sanctions risk perceptions will come

quickly or easily. However, data collection on the noncapital component of

the sanction regime need not be entirely complete to be useful. Moreover,

even if research on perceptions of the risk of capital punishment cannot

resolve all major issues, some progress would be an important step forward.

The ultimate success of the research may depend on the specific ques-

tion that is addressed. Questions of interest include

• if or how the legal status of the death penalty affects homicide

rates,

• if or how the intensity of use of the death penalty affects homicide

rates, and

• iforhowexecutionsaffecthomicideratesintheshortrun.

Some but not all of these questions may be informed by successful applica-

tion of the committee’s suggested lines of research.

Although evaluation of research on the deterrent effect of noncapital

sanctions was not part of the committee’s charge, we note that the methods

and approaches used to study capital and noncapital sanction effects on

crime overlap. We were charged with making suggestions for advancing

research on the latter issue. Thus, the research and data collection sugges-

tions above are framed in the broader context of research on the effect on

crime rates of both capital and noncapital sanctions.

We think this aspect of our charge is particularly important. Although

capital punishment is a highly contentious public policy issue, policies on

prison sanctions and their enforcement are the most important components

of the nation’s response to crime. Thus, even if the research agenda we

outline is not ultimately successful in illuminating some aspects of the ef-

fect of capital punishment on homicide, advancing knowledge on the crime

prevention effects of noncapital sanctions and their enforcement can make

major contributions to important policy issues.

REFERENCE

National Research Council. (1978). Deterrence and Incapacitation: Estimating the Effects of

Criminal Sanctions on Crime Rates. Panel on Research on Deterrent and Incapacitative

Effects. A. Blumstein, J. Cohen, and D. Nagin (Eds.), Committee on Research on Law

Enforcement and Criminal Justice. Assembly of Behavioral and Social Sciences.Washing-

ton, DC: National Academy Press.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

1

Introduction

I

n 1976 the Supreme Court decision Gregg v. Georgia (428 U.S. 153)

ended the 4-year moratorium on executions that had resulted from its

1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia (408 U.S. 238). In Furman the

Court had ruled that the death penalty, as then administered in the United

States, constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth

Amendment to the Constitution. Then, in Gregg, it had ruled that the death

penalty is not, in all circumstances, cruel and unusual punishment, thereby

opening the way for states to revise their capital punishment statutes to

conform to the requirements of Gregg.

In the immediate aftermath of Gregg, a National Research Council

report reviewed the evidence relating to the deterrent effect of the death

penalty that had been published through the mid-1970s. That review was

highly critical of the available research, concluding (1978, p. 9):

The flaws in the earlier analyses finding no effect and the sensitivity of

the more recent analysis to minor variations in model specification and

the serious temporal instability of the results lead the panel to conclude

that available studies provide no useful evidence on the deterrent effect of

capital punishment.

THE CURRENT DEBATE

During the 35 years since Gregg, and particularly in the past decade,

many studies have renewed the attempt to estimate the effect of capital

punishment on homicide rates. Most researchers have used post-Gregg

data from the United States to examine the statistical association between

9

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

10 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

homicide rates and the legal status or the actual implementation of the

death penalty.

The studies have reached widely varying, even contradictory, conclu-

sions, and commentary on the findings has sometimes been acrimonious.

Some researchers have concluded that deterrent effects are large and robust

across datasets and model specifications. For example, Dezhbakhsh, Rubin,

and Shepherd (2003, p. 344) concluded that:

Our results suggest that capital punishment has a strong deterrent effect;

each execution results, on average, in eighteen fewer murders with a mar-

gin of error of plus or minus ten. Tests show that results are not driven by

tougher sentencing laws and are robust to many alternative specifications.

Similarly, Mocan and Gittings (2003, p. 453) stated the following:

The results show that each additional execution decreases homicides by

about five, and each additional commutation increases homicides by the

same amount, while an additional removal from death row generates one

additional murder.

In 2004 testimony before Congress, Shepherd (2004, p. 1) summarized this

line of evidence on the deterrent effect of capital punishment as follows:

Recent research on the relationship between capital punishment and crime

has created a strong consensus among economists that capital punishment

deters crime.

However, the claims that the evidence shows a substantial deterrent

effect have been vigorously challenged. Kovandzic, Vieraitis, and Boots

(2009, p. 803) concluded that:

Employing well-known econometric procedures for panel data analysis,

our results provide no empirical support for the argument that the exis-

tence or application of the death penalty deters prospective offenders from

committing homicide . . . policymakers should refrain from justifying its

use by claiming that it is a deterrent to homicide and should consider less

costly, more effective ways of addressing crime.

Others do not go so far as to claim that there is no deterrent effect, but

instead argue that the findings supporting a deterrent effect are fragile, not

robust. Donohue and Wolfers (2005, p. 794) reanalyzed several of the data

sets used by the authors who claimed to have found robust deterrent effects

and concluded that:

We find that the existing evidence for deterrence is surprisingly fragile,

and even small changes in specifications yield dramatically different re-

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

INTRODUCTION 11

sults. Our key insight is that the death penalty—at least as it has been

implemented in the United States since Gregg ended the moratorium

on executions—is applied so rarely that the number of homicides it can

plausibly have caused or deterred cannot be reliably disentangled from the

large year-to year changes in the homicide rate caused by other factors.

Berk (2005, p. 328) reached a similar conclusion:

. . . the results raise serious questions about whether anything useful about

the deterrent value of the death penalty can ever be learned from an obser-

vational study with the data that are likely to be available.

Not surprisingly, the criticisms of the research claiming to have found

deterrent effects have generated defenses of the research findings and the

methodologies used, as well as counterclaims about the deficiencies in

the methods used by the critics. For instance, in response to the Kovandzic,

Vieraitis, and Boots (2009) claim of no deterrent effect, Rubin (2009,

p. 858) argued that:

the weight of the evidence as well as the theoretical predictions both argue

for deterrence, and econometrically flawed studies such as this article are

insufficient to overthrow this presumption.

In response to Donohue and Wolfers (2005, 2009), Zimmerman (2009,

p. 396) argued that:

This paper shows that many of D&W’s [Donohue and Wolfers] criticisms

of Zimmerman’s original work do not hold up under scrutiny, and other

authors have also rebutted D&W’s criticisms of their research.

Beyond disagreement about whether the research evidence shows a

deterrent effect of capital punishment, some researchers claim to have

found a brutalization effect from state-sanctioned executions such that

capital punishment actually increases homicide rates (see, e.g., Cochran and

Chamlin, 2000; Thomson, 1999). Evidence in support of a brutalization

effect is mostly the work of sociologists, but it is notable that in her latter

work Shepherd also concluded that brutalization effects may be present

(Shepherd, 2005).

COMMITTEE CHARGE AND SCOPE OF WORK

The Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty was organized

against this backdrop of conflicting claims about the effect of capital pun-

ishment on homicide rates, with the following charge:

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

12 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

This study will assess the evidence on the deterrent effect of the death

penalty—whether the threat of execution prevents homicides. The focus

will be on studies completed since an earlier National Research Council

assessment (National Research Council, 1978). A major objective of this

study is to evaluate underlying reasons for the differing conclusions in

more recent empirical studies about the effects of the legal status and ac-

tual practice of the death penalty on criminal homicide rates. The commit-

tee will develop a report about what can be concluded from these studies

and also draw conclusions about the potential for future work to improve

upon the quality of existing evidence.

Issues and questions to be examined include the following:

1. Does the available evidence provide a reasonable basis for drawing

conclusions about the magnitude of capital punishment’s effect on

homicide rates?

2. Are there differences among the extant analyses that provide a ba-

sis for resolving the differences in findings? Are the differences in

findings due to inherent limitations in the data? Are there existing

statistical methods and/or theoretical perspectives that have yet to

be applied that can better address the deterrence question? Are the

limitations of existing evidence reflective of a lack of information

about the social, economic, and political underpinnings of homi-

cide rates and/or the administration of capital punishment that first

must be resolved before the deterrent effect of capital punishment

can be determined?

3. Do potential remedies to shortcomings in the evidence on the de-

terrent effect of capital punishment have broader applicability for

research on the deterrent effect of noncapital sanctions?

In addressing those questions, we focused on the studies that have been

undertaken since the earlier assessment (National Research Council, 1978).

That assessment has stood largely unchallenged: none of the recent work,

whatever its conclusion regarding deterrence, relies on the earlier studies

criticized in that report or attempts to rehabilitate the value of those studies.

It is important to make clear what is not in the committee’s charge.

Deterrence is but one of many considerations relevant to deciding whether

the death penalty is good public policy. Not all supporters of capital pun-

ishment base their argument on deterrent effects, and not all opponents

would be affected by persuasive evidence of such effects. The case for

capital punishment is sometimes based on normative retributive arguments

that the death penalty is the only appropriate and proportional response

to especially heinous crimes; the case against it is sometimes based on

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

INTRODUCTION 13

similarly normative claims that the sanctity of human life precludes state-

sanctioned killings, regardless of any possible social benefits of capital

punishment. Separate from normative considerations, deterrence is not the

only empirical issue relevant to the debate over capital punishment. Other

considerations include whether capital punishment can be administered in

a nondiscriminatory and consistent fashion, whether the risk of a mistaken

execution of an innocent person is acceptably small, and the cost of admin-

istering the death penalty in comparison with other sanction alternatives.

Although there is empirical evidence on the issues of discrimination,

mistakes, and cost, the charge to the committee does not include these

questions. Nor have we been charged with rendering an overall judgment

on whether capital punishment is good public policy. We have been tasked

only with assessing the scientific quality of the post-Gregg evidence on the

deterrent effect of capital punishment and making recommendations for

improving the scientific quality and policy relevance of future research.

In including recommendations for future research, the study’s statement

of task recognized that potential remedies to shortcomings in the evidence

on the deterrent effect of capital punishment on homicide might also be

used in the study of the crime prevention effects of noncapital sanctions.

Thus, this report also offers recommendations for improving the scientific

quality and policy relevance of that research.

The post-Gregg studies can be divided into two types on the basis of

the type of data analyzed. Panel data studies analyze sets of states or coun-

ties measured over time, usually from about 1970 to 2000. These studies

relate homicide rates over time and the jurisdictions covered to the legal

status of capital punishment or the frequency of executions or both. Time-

series studies generally cover only a single geographic unit, which may be

as large as a nation or as small as a city. These studies usually examine

whether there are short-term changes in homicide rates in that geographic

unit in the aftermath of an execution. We review and critique these two

types of studies separately because their design and statistical methods are

quite different.

Assessing the deterrent effect of the death penalty is much more than

a question of interest to social science research. It is a matter of importance

to U.S. society at large, and we expect that a potentially broad audience

will want to understand how the committee reached its conclusions. Yet

the research that the committee has had to appraise is a body of formal

empirical work that makes use of highly technical concepts and techniques.

The committee has been mindful of the importance of reaching as broad an

audience as possible while meeting the fundamental requirement that the

report be scientifically grounded. With this in mind, Chapters 1, 2, and

3 (as well as the summary) have been written for a broad, largely policy

audience, largely avoiding technical language. In contrast, Chapters 4 and

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

14 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

5 include some exposition and analyses that are aimed for the researchers

in the field.

Chapter 2 summarizes homicide rates and the legal status and practice

of execution in the United States from 1950 to the present. Chapter 3 pro-

vides an overview of the possible mechanisms by which the legal status and

practice of execution might affect homicide rates and also provides a non-

technical primer on some of the key challenges to making valid inferences

about the deterrent effect of the death penalty. Chapters 4 and 5 review and

assess the panel and time-series studies, respectively. Chapter 6 elaborates

on the theoretical and statistical challenges to drawing valid conclusions

about the deterrent effect of the death penalty, and presents our conclusions

and recommendations for future research.

REFERENCES

Berk, R. (2005). New claims about executions and general deterrence: Déjà vu all over again?

Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 2(2), 303-330.

Cochran, J.K., and Chamlin, M.B. (2000). Deterrence and brutalization: The dual effects of

executions. Justice Quarterly, 17(4), 685-706.

Dezhbakhsh, H., Rubin, P.H., and Shepherd, J.M. (2003). Does capital punishment have a

deterrent effect? New evidence from postmoratorium panel data. American Law and

Economics Review, 5(2), 344-376.

Donohue, J.J., and Wolfers, J. (2005). Uses and abuses of empirical evidence in the death

penalty debate. Stanford Law Review, 58(3), 791-845.

Donohue, J.J., and Wolfers, J. (2009). Estimating the impact of the death penalty on murder.

American Law and Economics Review, 11(2), 249-309.

Kovandzic, T.V., Vieraitis, L.M., and Boots, D.P. (2009). Does the death penalty save lives?

Criminology & Public Policy, 8(4), 803-843.

Mocan, H.N., and Gittings, R.K. (2003). Getting off death row: Commuted sentences and the

deterrent effect of capital punishment. Journal of Law & Economics, 46(2), 453-478.

National Research Council. (1978). Deterrence and Incapacitation: Estimating the Effects of

Criminal Sanctions on Crime Rates. Panel on Research on Deterrent and Incapacitative

Effects, A. Blumstein, J. Cohen, and D. Nagin (Eds.). Committee on Research on Law

Enforcement and Criminal Justice. Assembly of Behavioral and Social Sciences. Wash-

ington, DC: National Academy Press.

Rubin, P.H. (2009). Don’t scrap the death penalty. Criminology & Public Policy, 8(4), 853-859.

Shepherd, J.M. (2004). Testimony on Crime and Deterrence: Hearing on H.R. 2934, the

Terrorist Penalties Enhancement Act of 2003. Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and

Homeland Security, House Judiciary Committee. Available: http://judiciary.house.gov/

legacy/shepherd042104.pdf [January 2012].

Shepherd, J.M. (2005). Deterrence versus brutalization: Capital punishment’s differing impacts

among states. Michigan Law Review, 104(2), 203-255.

Thomson, E. (1999). Effects of an execution on homicides in California. Homicide Studies,

3(2), 129-150.

Zimmerman, P.R. (2009). Statistical variability and the deterrent effect of the death penalty.

American Law and Economics Review, 11(2), 370-398.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

2

Capital Punishment in

the Post-Gregg Era

T

he resurgence in the use of the death penalty in the aftermath of

Gregg, which followed the de facto moratorium of the 1960s and

early 1970s, created the empirical basis for the post-Gregg capital

punishment deterrence studies. This chapter provides an empirical summary

of the legal status and use of capital punishment during this period.

EXECUTIONS AND DEATH SENTENCES OVER TIME

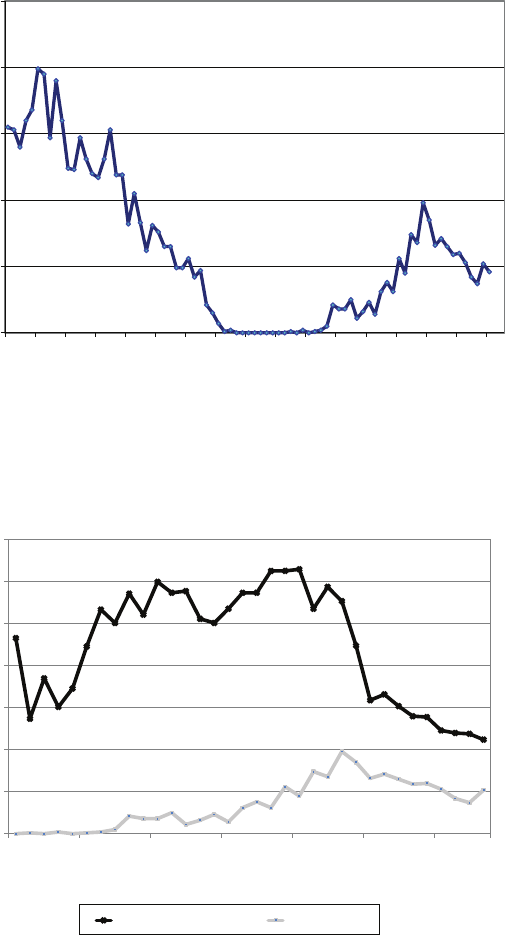

Figure 2-1 shows executions in the United States from 1930 through

2010. As can be seen, executions were more common prior to World War II

than in the postwar era. Executions peaked at 199 in 1935. Following the

war, executions steadily declined, from 153 in 1947 to 0 in the late 1960s.

From 1967 to the Furman decision in 1972, there were no executions even

though they were legally permissible. (The Furman rendered executions

legally impossible from 1972 through 1976.) Following the Gregg decision

in 1976, the number of executions rose rather steadily to the 1999 peak

of 98. It then began falling again: by 2005, the number of executions had

nearly halved to 53. Since 2005 the number of executions has remained

stable at about 50 per year. From 1976 to 2010, a total of 1,234 people

were executed.

Also relevant to the evidence on deterrence is the number of death sen-

tences imposed: Figure 2-2 shows the number of those sentences, as well

as the number of executions, for the post-Gregg period. In 1977, the first

full year following the Gregg decision, 137 death sentences were imposed.

Thereafter, death sentences rose to an annual peak of about 300 in the late

15

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

16 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

0

50

100

150

200

250

1930 1950 1970 1990 2010

Annual Number of Executions in the United States

Year

R02175

Figure 2-1

vectors, editable

FIGURE 2-1 Annual number of executions in the United States from 1930 to 2010.

SOURCE: Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010, Figure 2).

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 2001 2006

ExecutionsDeath Sentences

Year

Number

R02175

Figure 2-2

vectors, editable

2009

FIGURE 2-2 Annual number of death sentences and executions in the United States

from 1976 to 2009.

SOURCE: Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010, Tables 13, 19).

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE POST-GREGG ERA 17

1990s. Since then there has been a steady decline, to 112 in 2009. Figure

2-2 makes clear that far more death sentences are imposed than are carried

out.

When a defendant is convicted and sentenced to death, theoretically

what follows is an execution. An execution, however, does not follow a

death sentence very swiftly or at all for a variety of reasons. The Bureau of

Justice Statistics reports that only 15 percent of people sentenced to death

between 1973 and 2009 had been executed by the end of 2009. Of these

cases, 46 percent ended in alternate ways, including reversed convictions,

commuted sentences, or the death of the inmate. Thus, 39 percent of the in-

mates sentenced to death during the 36-year period were still on death row

in December 2009. These inmates, on average, had been under a death sen-

tence for more than 12 years. Because of the smaller number of executions

than death sentences every year, the death row population has increased

steadily over this period. The number of prisoners facing a death sentence

was a little over 400 in 1977 (the first full year after reinstatement); by 2009

it was close to 3,200 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010, Table 18).

These national-level data conceal large differences across states in the

use of the death penalty. During the post-Gregg era, the death penalty was

not legal in all states, and in some states it was only legal for part of the

period. Also, among states authorizing the death penalty, in at least some

cases there were very large differences in the extent of the legal authority for

capital punishment and the frequency with which that authority was used.

Notably, these variations across states and over time in the legal authority

to impose the death penalty and the frequency with which that authority

was exercised created the empirical basis for the deterrence studies reviewed

in this report.

Table 2-1 shows the legal authority for a death sentence by state from

1976 to 2009. A geographically and otherwise diverse group of 10 states

never authorized the use of the death penalty during this period: Alaska,

Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Vermont,

Wisconsin, and West Virginia. Of the other 40 states, 29 provided that au-

thority for the whole period. The remaining 11 states experienced changes

in death penalty authority from 1976 to 2009:

• Two states—North Carolina and Wyoming—transitioned in 1977,

immediately after the Gregg decision.

• Four states—Kansas, New Hampshire, Oregon, and South

Dakota—transitioned from non–death penalty to death penalty

status after 1977.

• Two states—New Mexico and Rhode Island—transitioned from

death penalty to non–death penalty status after 1977.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

18 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

TABLE 2-1 Legal Status of Execution in the Post-Gregg Era

State Legal Authority for Death Penalty 1976-2009

Alabama Yes

Alaska No

Arizona Yes

Arkansas Yes

California Yes

Colorado Yes

Connecticut Yes

Delaware Yes

Florida Yes

Georgia Yes

Hawaii No

Idaho Yes

Illinois Yes

Indiana Yes

Iowa No

Kansas No, 1976-1992; Yes, 1993-2009

Kentucky Yes

Louisiana Yes

Maine No

Maryland Yes

Massachusetts No, 1977-1979; Yes, 1980-1983; No, 1984-2009

Michigan No

Minnesota No

Mississippi Yes

Missouri Yes

Montana Yes

Nebraska Yes

Nevada Yes

New Hampshire No, 1976-1989; Yes, 1990-2009

New Jersey No, 1976-1981; Yes, 1982-2005; No, 2006-2009

New Mexico Yes, 1976-2007; No, 2008-2009

New York No, 1976-1994; Yes, 1995-2006; No, 2007-2009

North Carolina No, 1976; Yes, 1977-2009

North Dakota No

Ohio Yes

Oklahoma Yes

Oregon No, 1976-1977; Yes, 1978-2009

Pennsylvania Yes

Rhode Island Yes, 1976-1983; No, 1984-2009

South Carolina Yes

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE POST-GREGG ERA 19

State Legal Authority for Death Penalty 1976-2009

South Dakota No, 1976-1978; Yes, 1979-2009

Tennessee Yes

Texas Yes

Utah Yes

Vermont No

Virginia Yes

Washington Yes

West Virginia No

Wisconsin No

Wyoming No, 1976; Yes, 1977-2009

SOURCES: Data from Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010), Rogers (2002), and Death Penalty

Information Center (2010b).

TABLE 2-1 Continued

• Three states—Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York—

transitioned from a non–death penalty to a death penalty status and back

to a non–death penalty status over the period.

Thus, from 1976 to 2009 there were 14 transitions in death penalty status

among the 50 states. This fact has important implications for estimating

the deterrent effect of providing the legal authority for the death penalty

independent of the frequency of its use. This issue is discussed at length in

Chapter 5.

There is considerable variation among states that authorize the death

penalty regarding the types of cases in which death is an allowable punish-

ment. While deterrence studies often focus on homicide rates, there are no

states in which the death penalty is available for all intentional homicides.

First, not all intentional homicides are murders: many prosecutions that

begin as homicide cases are mitigated to the lesser crime of manslaughter,

for which capital punishment is never available. Second, even in most states

that authorize the death penalty, capital punishment is only available for

the relatively narrow category of “first-degree” murders, typically those

committed with “premeditation” or those committed during the course of

serious felonies. Finally, even those guilty of first-degree murder can only

be sentenced to death if the jury finds one or more specified aggravating

circumstances. These specified circumstances vary somewhat from state

to state, but typically include such factors as the murder of a police of-

ficer or witness, murder for hire, murder by a sentenced prisoner, multiple

murders or killings that caused a serious risk of death to many people, and

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

20 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

murders that are especially “heinous, atrocious, or cruel,” which is gener-

ally interpreted to mean killings that inflicted torture or extreme degrees

of physical or psychological pain on the victim beyond that inherent in the

act of killing.

The research reviewed in this report is not always clear in its use of

such terms as “homicide” and “murder.” Homicide is a generic term mean-

ing the killing of one human being by another (as distinct from suicide or

accidental death). Some homicides (e.g., killings in legitimate self-defense or

executions pursuant to judicial judgment) are not criminal at all. Criminal

homicides are subdivided into various categories of crime (e.g., murder,

manslaughter, negligent homicide), depending on whether the person caus-

ing death intended to do so or was merely reckless or negligent and on other

circumstances surrounding the killing, and these categories are often further

subdivided into degrees (e.g., murder in the first degree). Capital punish-

ment is typically only available for the most serious instances of murder.

Most of the studies we reviewed examine the association between

capital punishment and the combined number or rate of all types of non-

negligent homicides. Unless the specific context dictates otherwise, we use

the term “homicide” in describing the findings from the research. When

discussing the effect of capital punishment in a broader or more conceptual

sense, we use the term “murder,” since the conduct that the death penalty

typically aims to deter is unjustified intentional killing, which often (but not

always) falls into that legal category.

We recognize that neither of these usages is entirely precise as a reflec-

tion of legal categories, but the legal complexity (and diversity across the

states) of the legal categories, and the general tendency of the social science

literature to ignore these distinctions altogether, leave us with no entirely

satisfactory alternative.

USE OF THE DEATH PENALTY

As we discuss in Chapter 3, there are no data on the fraction of mur-

ders that are eligible for capital punishment, and studies of this issue have

reached varying conclusions. One nationwide study (Fagan, Zimring, and

Geller, 2006) concluded that about 25 percent of homicides are capital

eligible; in contrast, a Missouri study estimated that more than 70 per-

cent of all intentional homicides were at least theoretically capital eligible

(Barnes, Sloss, and Thaman, 2009). However, these kinds of studies are

inherently problematic. In the absence of an authoritative adjudication,

the “facts” of any given homicide can only be gleaned from police reports

and other accounts that do not necessarily reliably describe the facts that

could be proven sufficiently in a court of law to support a finding of capital

eligibility.

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE POST-GREGG ERA 21

Whatever the percentage of homicides that could hypothetically be

charged as capital, the percentage that are so charged, even at a very early

stage of the criminal process, is much smaller, and the number in which a

capital verdict is handed down, or a defendant actually executed, is minute

in comparison to the homicide rate. Cook (2009) reports that in North

Carolina for the fiscal years 2005 and 2006, 26.5 percent of murder ar-

raignments (N = 1,034) were initially charged as capital offenses, and of

those that were capitally prosecuted 4 percent were ultimately sentenced

to death.

The Cook study also illustrates that, even if a case is initially treated

by prosecutors as capital eligible, it is very unlikely to result in a death

sentence. There were many reasons for the precipitous drop-off in capital

cases between arraignment and sentencing. A small fraction of cases were

dismissed or found not guilty at trial. More commonly, defendants pleaded

guilty and received a noncapital sentence in return for the plea. In jury

trials, some individuals were found guilty of manslaughter or second-, not

first-, degree murder, and among those found guilty of first-degree murder

most juries did not recommend the death penalty.

Table 2-2 shows summary statistics on the frequency of executions

and death sentences from 1973 to 2009 for the 40 states with active death

penalty laws during at least part of the period. We focus on this time period

because it is the one used in most panel studies of deterrence. The table

shows that executions were very concentrated in a few states. Texas ac-

counted for 37.6 percent of executions from 1973 to 2009; Florida, Texas,

and Virginia together accounted for 52.2 percent. This concentration is only

partly attributable to more frequent imposition of the death penalty by the

courts in those states. Other large states, such as California and Pennsylva-

nia, impose relatively large numbers of death sentences. However, the rate

at which death sentences are actually carried out varies greatly across states.

The last column in Table 2-2 is the ratio of total executions to total death

sentences. In California and Pennsylvania, it is only 1.4 percent and 0.8

percent, respectively, compared with 7.0 percent in Florida, 43.0 percent

in Texas, and 70.0 percent in Virginia.

Table 2-2 makes clear that in many states death sentences will either

never be carried out or will only be carried out after a very long delay. This

fact is important for considering the deterrent effect of the death penalty be-

cause the longer the delay the more the death penalty resembles a sentence

of life without parole, the next most severe sanction to execution. It also

complicates the assessment of what features of a capital punishment regime

should be tested for an effect on homicide rates: the legal status of capital

punishment as a potential sanction, the rate of capital sentences, the rate of

executions, or the time to execution. We return to this point in Chapter 3.

Table 2-3 provides perspective on the frequency of executions and

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

22 DETERRENCE AND THE DEATH PENALTY

TABLE 2-2 Number of Death Sentences and Executions by Jurisdiction,

1973-2009

Death Sentences Executions

Executions per

Death Sentence

Federal 65 3 0.0462

Alabama 412 44 0.1068

Arizona 286 23 0.0804

Arkansas 110 27 0.2455

California 927 13 0.0140

Colorado 21 1 0.0476

Connecticut 13 1 0.0769

Delaware 56 14 0.2500

Florida 977 68 0.0696

Georgia 320 46 0.1438

Idaho 42 1 0.0238

Illinois 307 12 0.0391

Indiana 100 20 0.2000

Kansas 12 0 0

Kentucky 81 3 0.0370

Louisiana 238 27 0.1134

Maryland 53 5 0.0943

Massachusetts 4 0 0

Mississippi 190 10 0.0526

Missouri 182 67 0.3681

Montana 15 3 0.2000

Nebraska 32 3 0.0938

Nevada 147 12 0.0816

New Hampshire 1 0 0

New Jersey 52 0 0

New Mexico 28 1 0.0357

New York 10 0 0

North Carolina 528 43 0.0814

Ohio 401 33 0.0823

Oklahoma 350 91 0.2600

Oregon 58 2 0.0345

Pennsylvania 399 3 0.0075

Rhode Island 2 0 0

South Carolina 203 42 0.2069

South Dakota 5 1 0.2000

Tennessee 221 6 0.0271

Texas 1,040 447 0.4298

Utah 27 6 0.2222

Virginia 150 105 0.7000

Washington 38 4 0.1053

Wyoming 12 1 0.0833

TOTAL 8,115 1,188

SOURCE: Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010, Table 20).

Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Deterrence and the Death Penalty

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE POST-GREGG ERA 23

death sentences relative to the frequency of homicides in the states that

provided the authority for capital punishment for all or part of the period

from 1990 to 1999, the post-Gregg decade in which the most executions

occurred. The final two columns in the table report the ratios of total death

sentences and total executions, respectively, to the total homicides for the

period. The statistics make clear that relative to total homicides, death

sentences are rare and executions ever rarer. Among states with more than

500 homicides, Oklahoma had the highest ratio of death sentences to homi-

cides, 4.9 percent. Those ratios for Texas and Virginia, the two states that

most frequently impose the death penalty were 2.1 percent and 1.4 percent,

respectively. The ratio of executions to homicides was even smaller. Among

states with more than 500 homicides, the rate never exceeds 1 percent ex-

cept in Virginia.

The data in Table 2-3 highlight two important challenges to inferring