HARM REDUCTION

INTERNATIONAL

www.hri.global

The Death Penalty

for Drug Oences:

Global Overview 2018

FEBRUARY 2019

Giada Girelli

Harm Reduction International

2

3The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

Giada Girelli

© Harm Reduction International, 2019

ISBN 978-0-9935434-8-7

Copy-edited by Richard Fontenoy

Designed by Mark Joyce

Published by Harm Reduction International

61 Mansell Street, Aldgate, London E1 8AN

Telephone: +44 (0)20 7324 3535

E-mail: o[email protected]

Website: www.hri.global

Harm Reduction International is a leading non-governmental organisation dedicated to reducing the

negative health, social and legal impacts of drug use and drug policy. We promote the rights of people

who use drugs and their communities through research and advocacy to help achieve a world where

drug policies and laws contribute to healthier, safer societies.

This publication has been produced with the nancial support of the European Union. The contents

of this publication are the sole responsibility of Harm Reduction International and can under no

circumstances be regarded as reecting the position of the European Union.

Acknowledgements

This report would not be possible without data made available or shared by leading human rights organisations and individual

experts, with many of them also providing advice and assistance throughout the drafting process. We would specically like to thank:

the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, Amnesty International, Hands O Cain, the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide,

the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty, the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran, The Rights Practice, the

Global Commission on Drug Policy, the International Drug Policy Consortium, Reprieve, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan,

the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, the Lawyers Collective, the Death Penalty Project, the Asian Network of People who Use Drugs,

Release, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, the Human Rights and Democracy Media Center ‘SHAMS’ in Palestine, Project 39A,

Odhikar, Foundation for Fundamental Rights, Justice Project Pakistan and the European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights. We are

also indebted to Samantha Chong, Rick Lines, Lucy Harry and Amal Ali.

Thanks are also owed to the following colleagues at Harm Reduction International for their helpful feedback and support in preparing

this report: Cinzia Brentari, Naomi Burke-Shyne, Catherine Cook, Edward Fox, Sarah Lowther, Emily Rowe, Gen Sander, Sam Shirley-

Beavan and Katie Stone.

Any errors are the responsibility of Harm Reduction International.

The Death Penalty for Drug Oences:

Global Overview 2018

HARM REDUCTION

INTERNATIONAL

Harm Reduction International

4

INTRODUCTION

Harm Reduction International (HRI) has monitored use of

the death penalty for drug oences worldwide since our rst

ground-breaking publication on this issue in 2007. This report,

our eighth on the subject, continues our work of providing

regular updates on legislative and practical developments

related to the use of capital punishment for drug oences, a

practice which is a clear violation of international human rights

law.

The 2018 Global Overview outlines key trends across the

at least 35 countries that retain the death penalty for drug

oences in law, and analyses data on death sentences and

executions from the last decade. Extensive examination

is provided on the divergent trends witnessed in 2018 of

falling execution numbers globally, and rising appeal for

reimplementation of the death penalty in some countries,

while considering the role public opinion plays in all of this.

Harm Reduction International opposes the death penalty in all

cases without exceptions, regardless of the person accused

and their conviction, the nature of the crime, and the method

of execution.

METHODOLOGY

Drug oences (also referred to as drug-related oences or

drug-related crimes) are drug-related activities categorised as

crimes under national laws; for the purposes of this report, this

denition excludes activities which are not related to tracking,

possession or use of controlled substances and related

inchoate oences (inciting, assisting or abetting a crime).

In retentionist states, capital punishment is typically applied

for the following drug oences: cultivating and manufacturing,

smuggling, tracking and importing/exporting controlled

substances. However, the denition of capital drug oences

can also include (among others): possession, storing and hiding

controlled substances; nancing drug oences; and inducing

or coercing others into using drugs.

Harm Reduction International’s research on the death penalty

for drug oences excludes countries where drug oences

are punishable with death only if they involve, or result in,

intentional killing. For example, in Saint Lucia (not included in

this report), the only drug-related oence punishable by death

is murder committed in connection with drug tracking or

other drug oences.

1

The death penalty is reported as ‘mandatory’ when it is the only

punishment that can be imposed for at least certain categories

of drug oences, or in the presence/absence of certain

circumstances.

The numbers that have been included in this report are drawn

from, and cross-checked against: ocial government reports

(where available) and state-run news agencies; judgments;

NGO reports and databases; United Nations (UN) documents;

media reports; scholarly articles; and communication with local

human rights advocates, organisations and groups. Every eort

has been taken to minimise inaccuracies, but there is always

the potential for error. HRI welcomes information or additional

data not included here.

Identifying current drug laws and controlled drugs schedules

can be challenging, due to limited reporting and recording

at national level, together with language barriers. Some

governments make their laws available on ocial websites;

where it was not possible to independently verify a specic law,

the report relies on credible secondary sources.

With respect to data on death row populations, death

sentences and executions, the margin for error is even

greater. In most countries, information around the use of the

death penalty is shrouded in secrecy, or opaque at best. For

this reason, many of the gures cited in this report cannot

be considered comprehensive, and have to be considered

minimum numbers of conrmed sentences and executions,

illustrative of how capital punishment is carried out for drug

oences. It is likely that real numbers are higher, in some cases

signicantly. Where information is incomplete, there has been

an attempt to identify the gaps. In some cases, information

among sources is discordant, due to this lack of transparency.

In these cases, HRI has made a judgement based on available

evidence.

When the symbol ‘+’ is found next to a number, it means that

the reported gure refers to the minimum conrmed number,

but according to credible reports real gures are likely to be

higher. Global and yearly gures are calculated by using the

minimum conrmed gures.

THE DEATH PENALTY FOR DRUG OFFENCES:

Global Overview 2018

5The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

Foreword 6

Executive summary 7

At a crossroads: an analysis of divergent trends 9

Progress towards abolition 10

Resurgence or expansion of the death penalty for drug oences 16

Public support for capital punishment and penal populism 17

Country-by-country analysis 22

Categories 22

Legislation table - high application states 28

High Application Low Application Symbolic Application Insucient Data

China 24 Egypt 30 Bahrain 33 Libya 38

Indonesia 25 Iraq 30 Bangladesh 33 North Korea 38

Iran 25 Lao PDR 31 Brunei Darussalam 37 Syria 38

Malaysia 26 Pakistan 31 Cuba 37 Yemen 38

Saudi Arabia 26 State of Palestine (Gaza) 32 India 34

Singapore 27 Taiwan 32 Jordan 34

Vietnam 27 Thailand 32 Kuwait 37

Mauritania 35

Myanmar 35

Oman 37

Qatar 35

South Korea 36

South Sudan 37

Sri Lanka 36

Sudan 36

United Arab Emirates 36

United States of America 37

CONTENTS

Harm Reduction International

6

We have reached a tipping point in the history of the death

penalty for drug oences. This abhorrent practice is now being

implemented with less frequency, thanks to the realisation

among countries that were once prolic executioners that the

death penalty is a futile practice.

Capital punishment does not deter people from using or

tracking drugs. There is an enormous amount of evidence in

support of this. In countries that have aggressively pursued the

death penalty in recent decades, the drug market continues to

ourish.

While failing in its primary goal of impacting the drug trade,

the death penalty has enacted misery on the lives of some of

society’s poorest and most vulnerable. Those sentenced to

face execution for drug oences are often people at the lowest

level of the trade, a number of whom may have entered it out

of coercion or simply having no economic choice. In these

scenarios, the legal system will only exploit their indigence,

as stories of no access to legal aid and sham trials are all too

common.

It has been heartening to see my home country of Malaysia

– spurred by the case of a man convicted for a low-level drug

oence – begin to explore full abolition of the death penalty,

with government ministers admitting its ineectiveness as a

deterrent. The country’s executions for drug oences have

dropped markedly in recent years, though the death row

population continues to grow – roughly three-quarters of

the more than 1,200 people there were convicted for drug

oences. Until the death penalty is done away with, the

risk remains of more people having to languish in horric

conditions awaiting implementation of a death sentence.

While there is optimism in Malaysia’s moves toward abolition

and the downward trend globally in executions, now is not the

time to celebrate. Progress is fragile, and Malaysia’s review of

abolition is causing unrest in some quarters that want to see

continuation of the death penalty. Furthermore, a bill is yet

to be laid before parliament to decide the issue. Meanwhile

in Iran, which has seen the starkest fall in executions for drug

oences, death sentences continue to be handed down with

regularity.

Worryingly, we are seeing the re-emergence of pro-death

penalty rhetoric from country leaders playing to populist

anti-drug sentiment. Bangladesh expanded use of the death

penalty for drug oences in 2018, citing the scourge of drugs

on the country’s youth and families. At the time of writing,

Sri Lanka’s president was threatening to end a 43-year

moratorium on executions and begin signing death warrants

for convicted drug trackers.

Drugs will forever be a lightning rod in political discourse, but

leaders cannot continue to be guided by ill-informed prejudice

against drug use. For too long, the evidence has been ignored

that punitive drug policies, including the death penalty, do

more harm than good to our societies.

To capitalise on this tipping point for the death penalty for

drug oences, total abolition has to be enacted. It is not good

enough that executions cease and people are still left at the

mercy of unjust legal processes and ultimately appalling death

row conditions. As Bangladesh and Sri Lanka underscore,

until there is abolition, the spectre of the death penalty’s

reimplementation will remain.

With regards to drug oences more broadly, this conversation

needs to go further than the death penalty. Punitive drug

policies are ineective and causing myriad harms to society.

If leaders truly want to protect their citizens and mitigate

harm, they must ground drug laws in dignity, human rights

and evidence. More and more countries are beginning to

understand this. Now is the time for them to accelerate change

and ensure past failures are not repeated in the future.

FOREWORD BY Professor Adeeba Kamarulzaman

Dean of Medicine, University of Malaya, Malaysia

7The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

The death penalty for drug oences is a clear violation of

international human rights law. Numerous international

authorities and legal scholars have rearmed this point,

including the UN Human Rights Committee as recently as

2018.

Since Harm Reduction International began monitoring the use

of this abhorrent practice in 2007, annual implementation of

the death penalty for drug oences has uctuated markedly.

Over 4,000 people were executed globally for these oences

between 2008 and 2018, with executions hitting a peak above

750 in 2015 (excluding China and Vietnam, where these gures

are a state secret). Notably, 2018 gures show a signicant

downward trend, with known executions falling below 100

globally.

Iran, among the most prolic executioners for drug oences,

passed reforms in 2017 which resulted in a drastic reduction in

the implementation of the death penalty. After a bloody stretch

from 2015-2016, there were no executions (for any oence)

carried out in Indonesia for a second consecutive year, and

Malaysia – once among the most resolute supporters of the

death penalty, including for drug oences – committed to total

abolition of the death penalty in 2018.

Yet, while executions are falling, thousands of people remain

on death row for drug oences. A number of these people

are at the lowest levels of the drug trade, socio-economically

vulnerable, are tried without due process and/or have

inadequate legal representation. In short, it appears that the

death penalty for drug oences is primarily reserved for the

most marginalised in society.

Other events in 2018 show that for every progressive step,

there is a regressive counter-narrative. In Bangladesh

and Sri Lanka, populist rhetoric against the ‘threat’ of the

‘drugs menace’ has seen leaders push for expansion or re-

implementation of the death penalty, while governments in the

Philippines and United States (among others) pointed to capital

punishment as an essential tool to confront drug tracking or

public health emergencies.

There is no evidence that the death penalty is an eective

deterrent to the drug trade – in fact, according to available

estimates, drug markets continue to thrive around the world,

despite drug laws in almost every country being grounded in

a punitive approach. The response to drug use and the drug

trade remains heavily politicised, frequently resulting in a

rejection of evidence, even when brutal crackdowns are shown

to inict countless harms and rights violations on society.

In December 2018, a record 120 countries voted in favour

of the Resolution on a moratorium on the use of the death

penalty at the 73rd Session of the UN General Assembly,

2

and

since 2008 the number of abolitionist countries crept up from

92 to 106 in 2017.

3

This is a positive trend, but when countered

by inammatory political rhetoric, progress is fragile at best.

Governments must ground their drug laws in rights, dignity and

evidence, and do away with the death penalty once and for all.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Harm Reduction International

8

THE DEATH PENALTY FOR DRUG OFFENCES

IN 2018: A SNAPSHOT

Drug oences are punishable by death in at least 35

countries and territories worldwide.

4

The total number of conrmed executions for drug

oences (excluding China, including very limited data from

Vietnam) between 2008 and 2018 is 4,366 (of which

3,975 were in Iran alone).

Only four of these countries executed individuals for drug

oences in 2018 (China, Iran, Singapore and Saudi Arabia).

It is likely that Vietnam carried out drug-related executions,

but because of state secrecy it is not possible to conrm

this.

At least 91 people were executed for drug oences in

2018 (excluding China and Vietnam).

This represents a 68.5% decrease from 2017, a fall

primarily driven by developments in Iran, where

executions for drug oences fell 90% (from 221 in 2017 to

23 in 2018).

Saudi Arabia was responsible for the most conrmed

drug-related executions in 2018 (at least 59).

Singapore executed nine people in 2018 (one more

than 2017), all of them for drug oences.

Over 7,000 people are currently on death row for drug

oences globally.

5

At least 13 countries sentenced a minimum of 149

people to death for non-violent drug oences in 2018.

A signicant proportion of those sentenced are foreign

nationals.

Civil society reports and UN investigations shed light

on the grave human rights abuses endured by many

individuals awaiting or risking execution: fair trial

violations; physical and psychological abuse; isolation;

and denial of food and water, among many others.

Table 1

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Global Executions

for Drugs

168

208

706

529

399

327

526

755

369

288

91

0

200

400

600

800

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

168

208

706

529

399

327

526

755

369

288

91

Global Executions for Drugs

(Minimum confirmed figures, excluding China)

1

Chart 1: Global Executions for Drugs

(minimum conrmed gures, excluding China)

9The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

In contrast with a global trend towards abolition, in the past

30 years the death penalty has been increasingly employed by

some states as a key element of repressive strategies aimed at

curbing drug use and/or drug tracking. Often, such strategies

are rooted in prejudice, fear, intimidation and violence, rather

than empirical and scientic evidence.

After decades of policies that rely on harsh punishment, and

the threat and spectacle of executions, there is no evidence

that the death penalty has any unique deterrent eect on

either the supply or the use of controlled substances. In fact,

the opposite appears to be true: the 2018 World Drug Report,

published by the UN Oce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC),

admits that in spite of punitive approaches to drug control,

the drug market is booming, and a “potential supply-driven

expansion of drug markets, with production of opium and

manufacture of cocaine at the highest levels ever recorded”

is expected.

6

The UNODC Regional Oce for Southeast

Asia – where most retentionist countries for drug oences

are located – recently acknowledged that the production

and tracking of methamphetamine in the region has been

increasing steadily, and is now reaching “alarming levels”.

7

Another common claim of retentionist governments is that

the death penalty is necessary to protect the health of their

citizens.

8

However, analysis by HRI suggests that no positive

correlation has been found between the imposition of the

death penalty and drug use or the protection of public health.

In particular, the latest data from UNODC show that high

application countries – such as Malaysia, Vietnam and Iran

– have larger documented populations of people who inject

drugs than countries that have abolished the death penalty

for drug oences, in law or in practice.

9

Similarly, Thailand,

Vietnam, Malaysia and China (all retentionist countries)

record higher prevalence of Hepatitis C among people who

inject drugs than their counterparts in the region which are

abolitionist in law or in practice (such as Sri Lanka, Cambodia

and Nepal).

10

These ndings mirror those of an earlier study conducted

by Professor Jerey Fagan, which found no evidence that

the death penalty deters drug tracking and states that

“comparisons of Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore show that

the rate of execution has no eect on the prices of drugs nor

on the relative rates of drug prevalence”.

11

An analysis of recent developments regarding the use of

the death penalty for drug oences points to the existence

of divergent while contemporaneous trends. This report

will deconstruct and assess these trends, and consider an

interesting third dynamic playing into both: public opinion on

the death penalty.

The rst notable trend is a shift away from the death penalty

for drug oences, also manifested by a substantial drop in

drug-related executions in 2018. The analysis below details

key national reforms that have progressively restricted the

application of the death penalty. It also highlights signicant

limitations of these reforms, in particular:

A failure to envisage fair, proportionate and humane

alternatives to the death penalty.

Restrictions to judicial discretion.

A limited impact on the imposition of death sentences in

practice – insomuch that thousands of individuals remain

on death row for non-violent drug oences around the

world, in inhumane conditions of detention.

The second and opposite trend is the resurgence of

discourses advocating for the death penalty as an essential

instrument of drug control.

This can be witnessed in populist contexts and is driven

by a rejection of evidence pointing to the lack of a unique

deterrent eect of the death penalty, and of health- and

evidence-based approaches to drug control. The rise of

populism has revamped local and international crackdowns

on drugs in many parts of the world, from the United States

to the Philippines and from Sri Lanka to Bangladesh: self-

pronounced anti-establishment leaders dismiss ‘politically

correct’ discourses of human rights, dignity and the rule of

law to launch anti-drug campaigns feeding o prejudice and

misinformation.

Finally, this report will examine surveys on public attitudes on

the death penalty in South East Asian countries, which reveal

surprisingly diverse public opinion on the topic.

AT A CROSSROADS:

AN ANALYSIS OF DIVERGENT TRENDS

Harm Reduction International

10

PROGRESS TOWARDS ABOLITION

In the past decade, progressive reforms restricting the

application of capital punishment for drug oences have

been adopted in at least ve out of the 35 countries that

retain the death penalty for drug oences. Some were the

result of domestic civil society activism,

12

or were preceded

by mounting international pressure; some followed a more or

less tacit acknowledgment on the part of national authorities

of the ineectiveness of capital punishment as a tool for drug

control. This is best exemplied by the case of Iran, where a

2017 amendment to the Law for Combating Illicit Drugs was

preceded by unexpectedly frank stances by prominent gures.

Mohammad Baqer Olfat, the deputy head of the judiciary,

stated: “The truth is, the execution of drug smugglers has had

no deterrent eect”,

13

and called for a revision of the anti-

narcotics law, joining the secretary of Iran’s Human Rights

Council and over half of the country’s lawmakers.

14

Similarly

throughout 2017, Jalil Rahimi Jahanabadi, MP and member

of the Parliament Legal and Judicial Committee, repeatedly

acknowledged the failure of executions to deter drug use and

drug tracking.

15

Globally, progress to restrict the scope of the death penalty

took three key forms:

a) Abolition of the death penalty for certain drug oences.

b) Abolition of the death penalty as a mandatory

punishment for drug oences in the presence of specic

circumstances, thus giving judges some degree of exibility

in sentencing.

c) Amendments to the denition of drug oences punishable

by death.

a) Abolition of the death penalty for certain drug oences

Since 2015, Vietnam and Thailand reviewed their laws

to remove certain drug oences from the list of crimes

punishable by death. In 2015, Vietnam adopted an amended

criminal code where the death penalty is abolished for eight

oences, including drug possession.

16

Other drug oences,

such as manufacturing, transporting and tracking specic

controlled substances, are still punishable by death.

17

A similar approach was followed by Thailand, which in 2017

confronted severe prison overcrowding by amending the

Narcotics Act B.E. 2522, with the eect of abolishing the death

penalty for selling drugs. The same reform also expanded

opportunities for legal defence. Before the amendment,

any person caught in possession of certain quantities of

controlled drugs was automatically tried for drug tracking;

now, the intention to sell drugs is presumed, but rebuttable by

presenting adequate evidence.

18

b) Abolition of the death penalty as a mandatory

punishment for drug oences in the presence of specic

circumstances

Singapore and Malaysia partially abolished the death penalty

as a mandatory punishment for drug oences. In 2013,

Singapore removed the death penalty from its Misuse of

Drugs Act as a mandatory punishment for drug tracking,

importing and exporting.

19

Judges can now exercise a

limited amount of discretion in sentencing in the presence

of specic circumstances – namely, the limited involvement

of the accused in the illicit activity, and her/his substantial

contribution to disrupting drug tracking (described more in

detail below).

A similar reform was passed by Malaysia in late 2017. The

amendment to the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Revised

1980), which entered into force in March 2018,

20

repeals the

mandatory death penalty for drug tracking, thus removing

a major obstacle to judicial discretion. Similarly to Singapore,

this discretion can only be exercised if the defendant satises

strictly dened requirements (described in more detail below).

c) Amendments to the denition of drug oences punishable

by death

In October 2017, the Guardian Council of Iran approved a

parliamentary bill which amended the Law for Combating

Illicit Drugs (2017 Iranian Bill),

21

most notably by raising

the minimum amounts required for drug oences to be

punishable by death. The threshold for capital punishment

of production and tracking

22

of natural substances (bhang,

Indian hemp juice, grass, opium and opium juice, residue) has

been raised from ve to 50 kilogrammes; while the relevant

amount of processed substances (heroin, morphine, cocaine

and other chemical derivatives of morphine or cocaine), once

30 grammes, is now two kilogrammes.

23

Carrying, storing and

hiding processed substances is now punishable by death in

cases where the oence involves over three kilogrammes of

such substances.

24

11The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

THE IMPACT OF THE REFORMS

The aforementioned and other national reforms have had

some positive impact on the ground. Most signicantly, the

steady decrease in (conrmed) global executions for drug

oences:

25

from 755 in 2015 to 369 conrmed executions in

2016, to 288 conrmed executions in 2017, and 91 conrmed

executions in 2018 (this represents a 68% drop from 2017 and

a 88% drop from 2015).

26

The latter is primarily due to a 90% decrease in drug-related

executions in Iran (from 221 conrmed executions

27

in 2017

to 23 in 2018).

28

With some exceptions, executions for drug

oences were put on hold in the country whilst thousands of

eligible sentences were being reviewed. The 2017 Iranian Bill

applies retroactively: in March 2018, the UN Special Rapporteur

on the Situation of Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of

Iran reported that over 5,000 individuals on death row or

imprisoned for life for drug oences – 90% of which are young

rst-time oenders – may see their sentence commuted.

29

In the past ten years, non-violent drug oences have

accounted for 23% to 66% of all executions globally. In 2018,

due to the impact of the Iranian reform (together with the

absence of executions in high-application countries such as

Indonesia and Malaysia) they only constituted 13% of total

global executions. In turn, global executions for all crimes saw

a 31% decline.

30

This shows how signicant domestic reforms

to narcotic laws can be in substantially reducing the application

of the death penalty overall.

Confirmed Executions in Iran

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Drugs

140

200

705

521

378

297

479

672

339

221

23

Other crimes

269

251

94

166

201

481

473

382

253

286

231

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Executions for drug offences Executions for other offences

1

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Drug Oences 140 200 705 521 378 297 479 672 339 221 23

Other Oences 269 251 94 166 201 481 473 382 253 286 231

Chart 2: Conrmed Executions in Iran

Global executions per year (minimum confirmed figures, excluding China)

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Executions for

drugs

168

208

706

529

399

327

526

755

369

288

91

Execs total

567

569

368

476

548

860

744

956

688

705

591

0

600

1200

1800

2008 2009

2010

2011

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

591

705

688

956

744

860

548

476

368

569

567

91

288

369

755

526

327

399

529

706

208

168

Executions for drug offences Executions for other offences

735

777

1074

1005

947

1187

1270

1711

1057

993

682

1

Chart 3: Global executions per year (minimum conrmed gures, excluding China)

Harm Reduction International

12

LIMITATIONS OF THE REFORMS

Notwithstanding their signicance in reducing the number

of people executed, central aspects of the aforementioned

reforms are problematic in their design and implementation.

As such, they risk obstructing the very progress towards

abolishing the death penalty they have contributed to.

a) Disproportionate alternatives and limited judicial

discretion

While substantial attention has been devoted to the review

of quantities of controlled substances ‘activating’ the death

penalty, other, less progressive provisions of the 2017 Iranian

Bill have received less scrutiny. In fact, newly inserted clauses

will likely expand capital punishment to new categories of

oences and oenders. The Abdorrahman Boroumand Center

for Human Rights in Iran (ABC) stressed the risk that individuals

who have not personally committed a crime will be sentenced

to death through collective liability, and expressed concern

regarding the potential for abusive interpretations of broad

and unclearly dened terms in the bill.

31

The 2017 Iranian Bill also fails to address credible and

systematic reports of torture and ill-treatment suered by

those arrested for drug oences with the aim of forcing

confessions, and grave violations of fair trial rights, such

as denial of legal representation in the early stages of

investigations.

32

Finally, although ocial information on the

review process is not available, civil society reports excessive

and disproportionate punishments being imposed as an

alternative to death sentences, in the form of excessive prison

terms, corporal punishment and/or nes.

“The mother of one drug defendant reports to ABC

that her son’s death sentence for a crime involving 450

grams of methamphetamine was converted to 30 years’

imprisonment and a ne of 200 million tomans (around

US$64,000) – a punishment she calls tantamount to the

death penalty”.

33

For reference, the average annual income of urban families

in Iran has been reported at around 37 million tomans

(US$8,800), with an average living cost of nearly 33 million

tomans. For rural families, the average annual income

registered is just over 20 million tomans (US$4,770).

34

Failure

to pay can lead to expropriation of assets, as well as additional

prison time. Such a provision is highly problematic, in that it

“intensies negative consequences faced by those sentenced,

many of whom are driven to drug activity out of poverty and

unemployment, and their families”.

35

Disproportionate alternative punishments are also prescribed

in the Malaysian and Singaporean reforms. Both laws limit

the discretion of judges to life imprisonment and caning as

alternative to the death penalty.

36

This limitation to judicial power is not exceptional. Rather, it is a

common feature of many domestic narcotics laws, and a visible

manifestation of the exceptionalism characterising repressive

drug policies. For example:

In Pakistan, when the relevant oence involves more

than ten kilogrammes of a controlled substance, the only

available punishments are the death penalty and life

imprisonment.

37

In Saudi Arabia, a death sentence can only be commuted

(irrespective of the crime, the controlled substance and

individual circumstances) to imprisonment for a minimum

of 15 years, agellation and a ne of at least 100,000 riyals

(around $26,600).

38

In Taiwan, the only possible alternative to capital

punishment for relevant drug oences is life

imprisonment.

39

In Thailand, the death penalty for selling drugs has been

replaced with life imprisonment and a ne.

40

Judicial discretion in Malaysia and Singapore is further

restricted via prosecutorial powers. In Singapore, this

happens through ‘certicates of assistance’, whose use and

impact was thoroughly scrutinised by Amnesty International in

2017.

41

The recent amendments to the countries’ respective narcotic

laws allowed judges to exercise a degree of discretion, but only

if and after a prosecutor certies that the convicted person

has provided substantial assistance in disrupting tracking

activities (details in the text box below).

42

This further manifests

the exceptionalism characterising drug control policies: “in

no other common law jurisdiction does the prosecution have

the power to tie the judge’s hands in this way and prevent the

exercise of discretion in capital cases”.

43

In parallel, several presumptions were kept in place. Firstly,

alleged oenders are presumed guilty of drug tracking any

13The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

time they are found in possession of a certain amount of

controlled substances (in Singapore as little as three grammes

of cocaine, roughly the equivalent of a cube of sugar; while

tracking over 30 grammes of cocaine is punishable with

death).

44

And secondly, possession, control and knowledge of

the nature of the substances are presumed in a broad range

of circumstances, thus placing the onus on the accused to

prove their innocence.

45

In Singapore, for example, a person

is presumed to be in possession of a drug anytime s/he has

in possession or under her/his control anything containing a

controlled substance, or keys to any place, premises or object

where a controlled substance is found.

46

In addition, a prosecutor’s determination of whether a person

‘deserves’ a discretionary sentence is dicult to appeal: in

Singapore, a judicial review is only allowed for cases in which

the prosecutor has acted in bad faith, or with malice.

Presumptions in drug cases: Singapore

and Malaysia

The Singapore Misuse of Drugs Act allows imprisonment

rather than the death penalty only if:

“(a) The convicted individual was involved in the drug crime

as a mere ‘courier’, meaning his involvement in the oence

was restricted —

(i) to transporting, sending or delivering a controlled

drug;

(ii) to oering to transport, send or deliver a controlled

drug;

(iii) to doing or oering to do any act preparatory to

or for the purpose of his transporting, sending or

delivering a controlled drug; or

(iv) to any combination of activities in sub-paragraphs (i),

(b) the public prosecutor certies that the individual has

substantively assisted the Central Narcotics Bureau in

disrupting drug tracking activities within or outside

Singapore”.

Similarly, judicial discretion in Malaysia can now be

exercised only if:

(a) There was no evidence of buying and selling of a

controlled substance at the time when the person

convicted was arrested;

(b) There was no involvement of agent provocateur; or

(c) The involvement of the person convicted was limited

to the role of courier (here dened as transporting,

carrying, sending or delivering a controlled substance);

AND

(d) that the person convicted has assisted an enforcement

agency in disrupting drug tracking activities within or

outside Malaysia.

The combined impact of the provisions expanding

prosecutorial powers, together with the several presumptions,

is a structurally prejudiced system of justice:

48

Because of the presumptions, and the strict standards for

their rebuttal, defendants are essentially guilty until proven

innocent, in violation of one of the most fundamental

tenets of the right to fair trial.

The substantial assistance test is inherently discriminatory:

the lower the position of the courier in the drug tracking

chain, the less likely it is that s/he will be able to provide

meaningful information, and thus be “certied” (even less

if the person has been coerced or forced into tracking.)

By denition, couriers operate at the peripheries of drug

markets, with little to no impact on decision-making

processes. These provisions are therefore double-edged

in allowing for clemency in favour of such a low-level,

powerless gure, while at the same time conditioning

such potential for clemency on their ability to provide

information that is likely to be unavailable to them.

Regardless of the amount and reliability of the information

shared, a person will only meet the “substantial assistance

test” if their cooperation had the eect of assisting in the

disruption of tracking activities.

The Singaporean law stresses that the determination of

the assistance is “at the sole discretion”

49

of prosecutors,

who have exclusive and ultimate authority. This opens up

substantial space for corruption and abuse, and violates

the fundamental principles of fairness and separation

of powers. A literal life or death decision is entrusted to

prosecutors (parties to the process with incentives to

convict, thus not neutral gures) and stripped from judges,

who can only – eventually – exercise a limited amount of

discretion in a later stage.

Harm Reduction International

14

b) Failure to reform discriminatory systems

The reforms failed to address systemic issues characterising

the imposition of the death penalty for drug oences. Those

convicted of capital drug oences are largely among the most

marginalised and vulnerable both within the drug market and

in society.

“A prison guard once told me that the death penalty is

a privilege reserved for the poor” – recounted a death

row lawyer in 2011.

50

It has now been six years since Singapore amended its Misuse

of Drugs Act. According to Amnesty International, fewer death

sentences were imposed in the country in the period between

2013 and 2017 in comparison to the ve years preceding the

reform, and the amendment halved the number of people

who would have been sentenced to death.

51

However, steady

annual increases in death sentences from 2013 onwards

suggest that the reform had a limited impact in practice.

52

Most notably, sentences and executions for drug tracking

now constitute a higher proportion of overall death sentences

and executions in Singapore: while around 50% of all

executions between 2008 and 2013 were for drug oences,

this gure rose to 89% between 2014 and 2018.

53

Amnesty

International also reports that out of 41 sentences pronounced

for drug oences in Singapore between 2013 and 2017, 34

were for non-violent crimes involving extremely low quantities

of drugs (less than 90 grammes of pure substance).

54

All executions carried out in Singapore in 2018 were for

non-violent drug oences. The stories of the defendants are

telling: Prabu Pathmanathan, a 31-year-old Malaysian, was

sentenced to death for drug tracking in 2014 after heroin

was found in a car he owned, but was not driving at the time of

the discovery. His family was informed of the execution a mere

week before it was scheduled, and none of the many requests

for review submitted to Singapore – including by the Malaysian

government – succeeded in halting the execution.

55

The 2017 Malaysian reform does not apply retroactively, and

continues to allow the imposition of capital punishment for

drug tracking, which is the most common crime for which

death sentences are meted out in the country.

56

As a result,

death sentences continue to be handed down, often as a result

of awed trials.

A 2018 study by the Penang Institute in Malaysia looked at

121 cases of death sentences pronounced by Malaysian High

Courts for drug tracking between 2012 and June 2018, and

found that 25.6% of them were overruled at appeal.

57

Taking

the overruling as an indication that the earlier judgment was

“either factually or lawfully incorrect, then this would imply

that a judicial error had occurred in the lower court”.

58

Such

a nding is somewhat positive, in that it suggests that higher

courts are eective in reviewing the judgments of lower

courts, and correcting potential mistakes. However, it also

emphasises the importance of access to strong legal defence

– which is often unavailable to the most vulnerable in society

due to resource constraints in the justice system and fair trial

violations. When this is absent, or the case is not properly

reviewed, then the risk of wrongful convictions (and thus

potentially executions) remains high.

The study further points to discrimination in death penalty

cases, nding that foreign nationals are half as likely to have

their Court of Appeal judgment revised, and that women

convicted for tracking drugs have considerably less chance

than their male counterparts of seeing their cases revised and

overruled.

59

As a consequence, hundreds remain on death row in Malaysia.

According to the latest data, 932 out of 1,279 people on death

row are awaiting execution for drug oences.

60

Moreover,

convictions for drug oences continue to drive the expansion

of death row in the country: while the overall death row

population grew 13.8% between 2017 and 2018, death row

prisoners for drug oences specically increased by 38%

during the same period.

61

This is far from an exceptional situation. In Vietnam, many of

the more than 650 people on death row are awaiting execution

for drug oences.

62

Meanwhile in Thailand, almost 60% of

the 539 people on death row as of December 2018 had been

convicted of drug oences. Notably, the overwhelming majority

of women awaiting execution in Thailand (76 out of 83) have

been convicted for drug oences.

63

These data conrm how

exceptionally repressive drug control strategies adopted by

many states are, as well as their dening impact on death row

and incarceration gures.

The Foundation for Fundamental Rights recently found that out

of 133 capital cases prosecuted under the Pakistani Control

of Narcotic Substances Act, every single death sentence was

15The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

pronounced primarily for possession-based oences, rather

than tracking or management of drug syndicates. In fact, in

30% of these cases at least one senior tracker was identied,

but only in 1% of cases were they subsequently charged

or arrested.

64

The Foundation for Fundamental Rights also

analysed the prisoners’ socio-economic backgrounds, and

noted that many of these people were mere ‘drug mules’,

who were either coerced or driven into drug tracking by

their socio-economic circumstances. Their median income

was signicantly lower than the minimum wage for unskilled

workers in the country, and over 40% of them were found to

be illiterate.

“There is little chance these individuals could be acting

independently or have acquired the narcotics they were

seized with via their own means. The average value of

the narcotics seized from each prisoner was roughly

1,600 times the prisoners’ median income”.

65

Foreign nationals, who often endure unique violations of their

fair trial rights, also constitute a substantial proportion of the

global death row population. In 2018, 569 foreign nationals

were awaiting execution in Malaysia (44% of all death row

prisoners), many for drug oences.

66

At least 29 of the 59

people executed for drug oences in Saudi Arabia in 2018

were foreign nationals, mostly from Pakistan and Nigeria.

Similarly, 60 out of 236 death row prisoners in Indonesia are

foreign nationals.

67

The charts below are illustrative of the

discrimination suered by foreign nationals in the country:

while less than 1% of police investigations into drug oences

were against foreigners in 2015 and 2016, they accounted for

almost 85% of those executed for drug oences in the same

period.

Table 1

Indonesians

99.5%

Foreign nationals

0.5%

Investigations 2015 - 2016

0.50%

Indonesians Foreign nationals

0.31%

99.69%

1

Table 1

Indonesians

16.70%

Foreign nationals

83.30%

Executions 2015 - 2016

83.30%

16.70%

Indonesians Foreign nationals

1

Chart 4: Police investigations (left) and executions (right) carried out for drug oences in Indonesia in 2015 and 2016,

against Indonesians and foreign nationals.

68

Investigations 2015 - 2016 Executions 2015 - 2016

Harm Reduction International

16

RESURGENCE OR EXPANSION OF THE

DEATH PENALTY FOR DRUG OFFENCES

In 2014-2015 – just as executions began to decrease globally

– a number of populist governments pledged to confront drug

emergencies through punitive drug control strategies centred

around judicial and extrajudicial killings.

Populism relies on a constant state of crisis and emergency.

69

As such, nothing ts a populist rhetoric better than the concept

of a war on drugs – of a domestic battleeld that requires

swift, direct and severe responses. Typically, populist leaders

identify an emergency or menace, and point to themselves

(not the international community, judges nor lawyers) as the

only authorities able and willing to confront the situation and

restore order. In a populist scenario, violence is performative:

it shows strength and control. Extrajudicial killings and the

death penalty are thus neither extreme nor unintended

consequences of populist policies, but rather essential

manifestations of power.

One of the rst indications of this trend was Indonesian

President Joko Widodo’s renewal of the ‘war on drugs’ in

the country in 2014. Widodo relied on a populist rhetoric in

support of this strategy: he denounced drugs as the number

one problem in the country,

70

and claimed Indonesia was in a

state of emergency because of drug use and tracking, and

that it could only be confronted with capital punishment.

71

In

support of this claim, the Indonesian president cited inated

data on drug dependence and drug-related deaths in the

country, the collection of which has since received criticism.

72

In January 2015, six people were executed for drug oences;

in April of the same year, eight more individuals were executed

for drug tracking.

73

This was a signicant shift for Indonesia,

which had only carried out four executions for drug oences

between 2008 and 2014, with a hiatus between 2009 and

2012. The last execution was carried out in Indonesia in July

2016;

74

however, authorities are adamant that no moratorium

is in place.

75

The resumption of capital punishment in 2015 was part of

an aggressive anti-drug campaign which continues to this

day, and features extrajudicial killings,

76

arbitrary detention,

77

compulsory treatment of people who use drugs

78

and refusal

by the president to consider clemency applications submitted

by death row prisoners convicted of drug oences.

79

In the neighbouring Philippines, President Duterte’s

crackdown on drugs – a centrepiece of his presidential

campaign

80

– has led to over 20,000 suspected extrajudicial

executions since June 2016

81

and is driving the reintroduction

of the death penalty for drug oences (a dedicated bill passed

the lower house of parliament in 2017, and is now sitting in the

senate).

82

“Duterte’s rise to power utilized penal populism by

presenting a clear narrative built on the anxieties felt

by the public. His aggressive rhetoric translated to a

promise of justice and sense of control via a strong

leader”.

83

The Philippines fully abolished the death penalty in 2006,

84

and is one of few countries in Asia to have ratied the

Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death

penalty.

85

The protocol bars signatory countries from carrying

out executions and reintroducing capital punishment.

86

However, with a pro-death penalty leader, arbitrary drug

arrests and detention in overcrowded cells

87

and a preliminary

investigation for crimes against humanity opened by the

International Criminal Court,

88

the country is on the extreme

fringe of the international community.

The brutal strategy implemented in the Philippines met the

praise of USA President Donald Trump, who commended

Duterte’s “unbelievable job on the drug problem”.

89

In March

2018, President Trump laid out a plan to confront the opioid

crisis in the US, which included the imposition of the death

penalty against drug trackers.

90

This declaration was followed

by a memorandum released by then-attorney general Je

Sessions, strongly encouraging United States Attorneys to

pursue capital punishment for drug tracking.

91

In July 2018, the government of the Indian state of Punjab

called for expanding the death penalty to rst-time drug

oenders, also citing “with approval, the examples of the

regimes in Saudi Arabia and Thailand chopping o the heads of

drug trackers as eective measures”.

92

India formally retains

the death penalty for drug oences, but only for a subsequent

oence involving possession, production or transportation of

specied drugs and quantities. As a consequence, only six of

the 915 death sentences conrmed to have been pronounced

in the country from 2011 onwards are for drug oences.

17The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

This proposal represented an escalation in the local

government’s ght against the “drug menace”,

93

a term used

to refer to growing opioid use in the area. The chief minister

of Punjab, Amarinder Singh, incited violence and introduced

increasingly repressive measures, from compulsory drug

testing of government employees to prohibiting the sale of

syringes without a prescription.

94

This move was eventually

rejected by the central government.

95

In July 2018, Sri Lanka’s President Maithripala Sirisena

quashed hopes for abolition by threatening to execute 19

convicted drug trackers, which would thereby end the

country’s 42-year-long de facto moratorium on the use of the

death penalty.

96

The president cited alleged drug tracking

being directed by prisoners as a driver of an alleged “growing

tide of drugs” in the country, and praised the successes of

President Duterte.

97

According to ocial gures, Sri Lanka

hands down dozens of death sentences each year.

98

If such

a decision is implemented, it could have tragic consequences

for death row prisoners in a country where possessing two

grammes of cocaine is enough to be sentenced to death.

99

Finally, on 27 October 2018, Bangladesh approved a new

Narcotics Control Act which expands the application of

capital punishment to the manufacture and distribution of

methamphetamine, known as yaba.

100

No execution has ever

been conrmed in Bangladesh for drug oences, and only one

drug-related death sentence was reported between 2008 and

2017, although more could have been pronounced.

101

Early

signs of a potential shift are the two death sentences handed

down for drug tracking in 2018.

102

This possible resurgence of the death penalty in the country is

not an isolated phenomenon, but rather part of a wider anti-

drug campaign which has created hundreds of victims since

it was launched in May 2018 by the country’s prime minister,

Sheikh Hasina. The prime minister armed in June of the same

year: “Drugs destroy a country, a nation and a family. […] We

will continue the drive, no matter who says what”.

103

Local human rights organisations denounced 292 extra-judicial

killings between May and December 2018 caused by the

government-backed war on drugs,

104

while credible evidence

emerged of mass arrests of over 25,000 individuals,

105

enforced

disappearances and obstacles to accessing healthcare services

for people who use drugs. This war on drugs is ultimately a

war on the poor, and a political strategy to spread fear ahead

of the general elections which took place on 30 December

2018.

107

UN experts denounced that:

“‘Slum’ areas have been particularly subjected to

raids and [...] the ‘war on drugs’ disproportionately

targets poor and underprivileged people. There are

also reports that lists of individuals to be subjected to

operations have been prepared, that members of the

RAB [Rapid Action Battalion] are accepting money not to

target certain individuals, and that in some cases killings

may have been politically motivated”.

108

PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR CAPITAL

PUNISHMENT AND PENAL POPULISM

Another key feature of populist governments is their symbiotic

relationship with the public and thus their strong focus on

public opinion.

On one side, populist policies are often designed with the aim

of building or strengthening public support. Not by chance,

they tend to become more visible, or more aggressive,

in the vicinity of elections (as developments in Indonesia

and Bangladesh show). A particular manifestation of this

phenomenon is penal populism, or “the idea that public support

for more severe criminal justice policies […] has become a

primary driver of policy making”.

109

Penal populism is identied

as a driver of the increase in the use of severe criminal

punishment, irrespective of its potential as well as adequacy

to reduce crime and confront issues, because of the public

support it garners. On the other side, populist discourses often

reject evidence, expert opinions and international standards,

pointing to popular support to justify and legitimise their

policies.

These dynamics are apparent both in the eld of drug control

and in relation to the use of capital punishment. Evidence

clearly shows that the death penalty, and violently repressive

policies in general, have no unique deterrent eect on drug

tracking (as illustrated above).

110

On the contrary, they

cause signicant health and social harm. However, this body

of evidence, together with basic human rights standards, are

rejected by populist leaders as biased or foreign, or simply

ignored; while drugs are reduced to a mere criminal issue, to

be confronted with harsh criminal measures. Accordingly, the

death penalty is paraded as an easy solution to complex and

Harm Reduction International

18

deep-rooted phenomena – which are often exacerbated by

misguided choices of those same governments.

Public opinion surveys play a critical role in perpetuating

this vicious cycle. They are often cited in support of, and as

nal justication for, repressive drug policies.

111

At a closer

look, however, the reality appears to be one of awed data

collection, cherry-picked results and conated rhetoric, with

public opinion being more complex and diverse than is often

reported.

In 2013, the Death Penalty Project published the results from

one of the most detailed public opinion surveys on the death

penalty conducted in an Asian country, focused on popular

perceptions in Malaysia.

112

This study highlighted the elasticity

of people’s attitudes towards capital punishment.

When asked about their support for the death penalty for

drug tracking generally, a staggering 74% to 80% of the

participants declared to be in favour (depending on the drug

involved).

113

However, once presented with specic cases,

responses changed considerably: none of the scenarios

involving a drug oence garnered more than 29% support, and

in one specic case (a woman drug courier with no criminal

record), the support plummeted to 9%.

114

Another key factor found to be inuencing popular attitudes

is the belief in perfect justice. When expressing their support

for the death penalty for drug tracking, if it was proven that

innocent people had been executed, approval fell almost 50

points, from 75% to 26%.

115

More recently, this same methodology was employed to assess

public attitudes in Singapore. Although the country is one

of the most resolute supporters of capital punishment as an

instrument of drug control, in part because of the perceived

support enjoyed from the population, the results largely mirror

those of Malaysia:

86.9% of participants claimed to support the death penalty

for drug tracking “in general”.

117

Once presented with real-life scenarios, attitudes changed

signicantly. For the case of a female drug courier, support

for the death penalty fell to 16.7%.

118

The main reason for supporting capital punishment is

belief in its deterrent eect, and in perfect justice: “[I]f it

was proved that innocent persons have sometimes been

executed […] between 61.5% and 67.6% of those who

supported the death penalty for at least one of the three

crimes [murder, drug tracking, rearm oences] would

change their minds”.

119

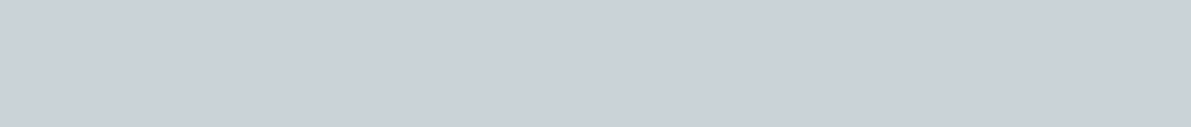

Chart 5: Public support for the death penalty for drug

oences

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

General/non-contextual

Aggravated scenario

Mitigated scenario

86.9%

46.7%

16.7%

77%

29%

9%

Malaysia Singapore

Table 1

Malaysia

Singapore

General/non-

contextual

77.0%

86.9%

Aggravated

scenario

29.0%

46.7%

Mitigated

scenario

9.0%

16.7%

1

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

General/non-contextual

Aggravated scenario

Mitigated scenario

86.9%

46.7%

16.7%

77%

29%

9%

Malaysia Singapore

Table 1

Malaysia

Singapore

General/non-

contextual

77.0%

86.9%

Aggravated

scenario

29.0%

46.7%

Mitigated

scenario

9.0%

16.7%

1

On 10 October 2018, the Human Rights Commission of the

Philippines released the results of a public opinion survey on

the death penalty for drug oences

120

which disproves the

ongoing narrative claiming the people are calling for capital

punishment to be reintroduced.

121

Respondents were given dierent scenarios, and tasked with

choosing among four dierent forms of punishment, including

the death penalty. The results suggest that the majority of

Filipinos do not support the death penalty for drug oences.

For the crimes of working in and maintenance of areas where

people use drugs, manufacture, sale or importation of illicit

drugs and murder under the inuence of drugs, only 22%

to 33% of respondents (depending on the specic oence)

believe that capital punishment is the most appropriate

response.

122

Consistent with the ndings of other surveys, the

main reason for supporting the death penalty is the belief in its

deterrent eect.

123

19The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

Innocence and perfect justice again proved to be key

determinants of opinion, with three in ve respondents

convinced that “the death penalty can only be imposed if

the courts are certain that they will not wrongfully execute

an innocent person”.

125

At the same time, Filipinos do not

seem to believe this perfect justice exists: almost half of the

survey respondents are convinced that most people in prison

are innocent, and three in ve are concerned that wrongful

sentencing is “very possible”.

126

These three surveys consistently recorded a general lack of

knowledge by the public around basic death penalty facts: the

overwhelming majority of respondents both in Malaysia

127

and

in Singapore

128

were unable to correctly estimate the number

of people executed for drug oences in the countries in the

previous ten years. Over half of Malaysian interviewees was

also not aware that (at the time of the survey) judges were

mandated to impose the death penalty for drug tracking.

129

Public opinion is often mentioned as a key justication for

retaining the death penalty for drug oences. This argument

is a fallacious one. On the one hand, public policies should

be centred around the respect for and protection of human

rights, not purely determined by public preferences. On the

other hand, the abovementioned surveys unequivocally show

that support for the death penalty – especially for non-violent

crimes – is elastic and contextual. Calls for capital punishment

are often rooted, and dependent on, the belief in (1) its ability

to deter crime and (2) the infallibility of the justice system, both

of which have been disproved.

CONCLUSIONS

Recent political, legal and practical developments with regards

to the death penalty for drug oences suggest we are in a

dening and critical moment.

On the one hand, several countries are progressively shifting

away from capital punishment as a tool of drug control, often

after acknowledging the failure of the death penalty to deter

drug use and drug tracking. The most visible consequence of

such shifts is a stark decrease in executions for drug oences,

and consequently overall (as the examples of Iran and Malaysia

show).

On the other hand, thousands of people continue to be

sentenced to death for non-violent drug oences around the

world, and endure harsh conditions of detention, sometimes

for decades, in crippling uncertainty about their future.

Governments inate perceived drug emergencies and push

for the imposition or expansion of the death penalty, often on

the basis of apparent popular support coupled with populist

discourses:

“The ‘war on drugs’ approach allows people to simplify

the complex nature of drug dealing and drug use. This

misleads people into thinking that tough laws alone

are a magic bullet that can deal with all drug-related

problems once and forever”.

130

Table 1

It deters crime

55%

It dispenses justice

37%

It solves the drug

problem

7%

It reduces the

number of prisoners

0.4%

It depends on the

situation

0.2%

Other reasons

1%

It deters crime

It dispenses justice

It solves the drug problem

It reduces the number of prisoners

It depends on the situation

Other reasons

0%

15%

30%

45%

60%

1%

0.2%

0.4%

7%

37%

55%

1

Chart 6: Findings from the March 2018 National Survey on Public Perceptions on the Death Penalty published by the

Human Rights Commission of the Philippines

124

REASON FOR AGREEING THAT THE DEATH PENALTY BE RE-INSTATED FOR PEOPLE PROVED BY

THE COURTS TO HAVE REALLY COMMITTED HEINOUS CRIMES.

(WS and Commission on Human Rights (2018) Special Report: March 2018 National Survey on Public Perceptions on the Death Penalty)

Harm Reduction International

20

Throughout this report, three recurring themes emerge,

which situate the death penalty as one of the most visible

manifestations of repressive approaches to drug use and

tracking, rather than an isolated measure.

First, the exceptionalism characterising punitive drug policies,

manifested by the sidelining of fundamental standards of

dignity and legality in favour of grossly disproportionate and

dehumanising responses. This is embodied (among others) by

the many presumptions, the mandatory character of the death

penalty or the disproportionate alternatives prescribed, and

the subjugation of judicial discretion to prosecutorial powers.

By preventing judges from considering the circumstances of

the crime and the accused, these features make it virtually

impossible to respect the fundamental principles of fairness

and proportionality that must characterise due process.

Notably, such a departure from fundamental standards of law

is not exclusive to the death penalty, but rather characterises

many punitive responses to drugs, as they are ultimately

rooted in misperception and prejudice: a person who engages

with drugs is by denition ‘guilty’, and as such not deserving of

the legal guarantees and fundamental protections aorded to

others.

The lack of proportionality, with capital punishment employed

to punish non-violent behaviours because of sometimes

minimal involvement of drugs, is also not limited to the death

penalty. Rather, it infuses repressive drug policies around the

world, as manifested by global rates of over-sentencing and

over-incarceration of people engaging – or suspected to be

engaging – with drugs.

131

“[H]arsh criminal justice responses

to drugs are a major contributor to prison overcrowding”, and

in certain countries the majority of the prison population has

been incarcerated for drug oences.

132

Second, the fundamentally discriminatory nature of the death

penalty, which reects the inherently inequitable character of

punitive drug policies.

Repressive responses to drugs around the world

disproportionately impact upon the most vulnerable, both in

society and within the drug market. In the same way, because

of the combination of lack of adequate legal aid, the imposition

of capital punishment for minor oences and structural

features of the drug market, death row prisoners in countries

retaining the death penalty for drug oences are largely

individuals with histories of poverty, discrimination and fragility,

convicted for often marginal involvement with drug tracking.

Due to the way drug control laws are designed and enforced,

the primary targets of law enforcement are individuals

occupying positions within the drug market characterised by

high risk and low reward (such as couriers).

133

Third, a rejection of evidence and evidence-based

interventions and approaches. This report has retraced

recurring discourses around the purported deterrent eect of

the death penalty on drug use and drug tracking – in contrast

with an increasing body of evidence denying it. The same

rhetoric, and the same dynamic, can be witnessed for punitive

drug policies more generally. While governments around the

world call for crackdowns on drug use and drug markets,

studies consistently nd that punishment and criminalisation

do not reduce either drug use or drug markets; in fact, drug

markets continue to expand.

134

The repressive climate in which

these measures are implemented fuels impunity and violence,

while negatively weighing on both individual and public health.

More generally, punitive drug policies around the world fail

to produce positive results because they ignore mounting

evidence about dening aspects of drug use and drug markets.

In the same way, the death penalty simply cannot work as a

tool of drug control and supply reduction, because in making

it the cornerstone of their drug policies, governments choose

to ignore the reasons that determine many to engage in the

drug market (such as coercion, ignorance of the consequences

or lack of economic opportunities) and the power dynamics

shaping it.

135

Finally, any measure that aims to work as a

deterrent must be predictable and certain. Domestic narcotics

laws, however, are extremely diverse and varied (as the table

at page 28 shows), each punishing dierent crimes, types and

quantities of drugs, insomuch that they are simply unt to

successfully deter any behaviour; even less those which are by

nature transnational, such as many drug oences.

In light of this, it becomes apparent that the limitations of

the reforms analysed throughout this report are not due

to the specicities of the context, nor to the laws. Rather,

they are to be attributed to the fundamental unfairness of

capital punishment, and of those repressive drug control

policies of which the death penalty is a manifestation. In other

words, a comparative analysis of these reforms and their

implementation shows that a death penalty reform which

falls short of total abolition will never be fair, because

both capital punishment and repressive drug control policies

21The Death Penalty for Drug Oences: Global Overview 2018

are inherently abusive, discriminatory, and contrary to basic

principles of humanity and dignity.

Domestic developments show that change is possible, and

that tackling the death penalty for drug oences is a strategic

step towards the achievement of total abolition of this

barbaric punishment. At the same time, recent reforms also

demonstrate how complex the struggle towards abolition is.

Examples such as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh demonstrate

how any change in policy or political will can undo decades of

advancements, if not resisted and counteracted with evidence,

education, compassion and human rights-based strategies.

Harm Reduction International

22

CATEGORIES

HRI has identied 35 countries and territories that retain the

death penalty for drug oences in law.

Only a small number of these countries carry out executions

for drug oences on a regular basis. In fact, ve of these

states are classied by Amnesty International as abolitionist

in practice.

136

This means that they have not carried out

executions for any crime in the past ten years (although in

some cases death sentences are still pronounced), and are

believed to have a policy or established practice of not carrying

out executions.

137

Others have never executed anyone for a

drug oence, despite having dedicated laws in place.

In order to demonstrate the dierences between law and

practice among states with the death penalty for drug oences,

HRI categorises countries into high application, low application

or symbolic application states.

High Application States are those in which the sentencing of

those convicted of drug oences to death and/or carrying out

executions is a regular and mainstream part of the criminal

justice system.

Low Application States are those where executions for drug

oences are an exceptional occurrence, although executions

for drug oences may have been carried out within the last ve

years, while death sentences for drug oences are relatively

common.

Symbolic Application States are those that have the death

penalty for drug oences within their legislation but do not

carry out executions, or at least there has not been any record

of executions for drug oences. Most of these countries are

retentionist, which, according to Amnesty International, means

that they retain the death penalty for ‘ordinary crimes’.

138