Publication 5550 (8-2021) Catalog Number 55082U Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service publish.no.irs.gov

Real Estate Property

Foreclosure and

Cancellation of Debt

Audit Technique Guide

This document is not an official pronouncement of the law or the position of the Service and cannot be

used, cited, or relied upon as such. This guide is current through the revision date. Since changes may

have occurred after the revision date that would affect the accuracy of this document, no guarantees are

made concerning the technical accuracy after the revision date.

The taxpayer names and addresses shown in this publication are hypothetical.

Audit Technique Guide Revision Date: 8/10/2021

2

Table of Contents

I. Overview .............................................................................................. 7

A. Background / History ..................................................................... 7

B. Exceptions ...................................................................................... 8

B.1. Gifts ......................................................................................... 8

B.2. Deductible Debt (Lost Deduction) ......................................... 8

B.3. Purchase Price Reduction ..................................................... 8

C. Relevant Terms .............................................................................. 9

D. Key Tax Issues ............................................................................. 10

II. Type of Debt - Nonrecourse and Recourse Debt ............................ 12

A. Nonrecourse Debt ........................................................................ 13

A.1. Nonrecourse Debt Examples ............................................... 14

B. Recourse Debt ............................................................................. 15

B.1. Recourse Debt Examples..................................................... 17

C. Gain and Loss Computation and Cancellation of Debt Income 17

D. Analysis of Disposition of Property Secured by Nonrecourse or

Recourse Debt ............................................................................. 18

III. Income from Discharge of Indebtedness and Items Specifically

Excluded from Gross Income ........................................................... 19

A. Bankruptcy ................................................................................... 21

A.1. Example ................................................................................. 21

A.2. Examination Consideration .................................................. 22

B. Insolvency .................................................................................... 22

3

B.1. Insolvency Calculation ......................................................... 22

B.2. Examples ............................................................................... 23

B.3. Examination Consideration ................................................. 25

B.4. Audit Techniques ................................................................. 25

C. Qualified Farm Indebtedness ...................................................... 26

C.1. Examples ............................................................................... 27

C.2. Examination Consideration ................................................. 28

D. Qualified Real Property Business Indebtedness ....................... 28

D.1. Example ................................................................................. 31

D.2. Examination Consideration ................................................. 32

E. Qualified Principal Residence Indebtedness ............................. 32

E.1. Indebtedness That Does Not Qualify ................................... 33

E.2. Examples ............................................................................... 34

E.3. Other Tax Considerations .................................................... 37

E.4. Examination Consideration ................................................. 38

E.5. Audit Techniques ................................................................. 38

IV. Tax Attribute Reduction .................................................................... 38

A. Reduction of Tax Attributes ........................................................ 38

A.1. Election to Reduce Basis First ............................................ 40

A.2. Election to Treat Certain Inventory as Depreciable Property

40

A.3. Depreciation Recapture Reductions ................................... 41

A.4. Summary of Tax Attribute Reduction Rules ....................... 41

4

B. Bankruptcy, Insolvency, and Farm - Attributes Reduction ....... 44

B.1. Bankruptcy Attribute Reduction Examples ........................ 45

B.2. Insolvency Attribute Reduction Examples ......................... 48

B.3. Other Considerations for Bankrupt or Insolvent Taxpayers

50

B.4. Basis Example ...................................................................... 51

B.5. Qualified Farm Indebtedness - Basis Attribute Reduction 53

C. Qualified Real Property Business Indebtedness - Attribute

Reduction ..................................................................................... 55

C.1. Recapture Reductions ......................................................... 55

C.2. Examples .............................................................................. 56

D. Qualified Principal Residence Indebtedness - Attribute

Reduction ..................................................................................... 59

D.1. Examples .............................................................................. 59

V. Rental Real Estate Property.............................................................. 61

A. Overview ....................................................................................... 61

B. Qualifying Dispositions Under IRC § 469(g) .............................. 61

C. Disqualifying Dispositions Under IRC § 469(g) ......................... 63

D. Depreciation Recapture ............................................................... 64

E. Character of Property at Disposition .......................................... 64

F. Lease with Option to Buy ............................................................ 65

G. Examples ...................................................................................... 65

H. Audit Strategies ........................................................................... 67

5

VI. Abandonments .................................................................................. 68

A. Tax Consequences of Abandonments ....................................... 68

B. Examples ...................................................................................... 70

VII. Form 1099-A and Form 1099-C ......................................................... 71

A. Background .................................................................................. 71

B. Example ........................................................................................ 72

C. Examination Considerations ....................................................... 73

D. Inaccurate or Questionable Forms 1099-A and 1099-C ............. 75

D.1. Form 1099-C Box 2. Amount of Debt Discharged .............. 75

D.2. Form 1099-A Box 4 & Form 1099-C Box 7. Fair Market

Value (FMV) of Property ......................................................... 75

D.3. Form 1099-A & Form 1099-C Box 5. Check here if the

Debtor was Personally Liable for Repayment of the Debt ... 76

D.4. Form 1099-C Box 6. Identifiable Event Code ...................... 76

VIII. Community and Common Law Property .................................... 77

A. Community and Common Law Property Systems..................... 77

B. Community Property ................................................................... 78

B.1. Income ................................................................................... 79

B.2. Deductions ............................................................................ 79

B.3. Gains and Losses ................................................................. 79

B.4. Community Property Examples........................................... 79

IX. Rehabilitation Credit and IRC § 469 ................................................. 81

A. Background .................................................................................. 81

B. Audit Hints .................................................................................... 82

6

X. Low Income Housing Credit & IRC § 469 ......................................... 83

A. IRC § 469 - $25,000 Offset ........................................................... 83

B. Disposition of Passive Activity ................................................... 83

XI. Audit Strategies and Case File Documentation .............................. 84

A. Summary of Real Estate Property Audit Strategies .................. 84

B. Case File Documentation ............................................................ 87

C. Standard Paragraphs and Explanation of Adjustments ............ 87

XII. Job Aids ............................................................................................. 87

A. Job Aid 1 - Insolvency Worksheet .............................................. 87

B. Job Aid 2 - Sample Information Document Request ................. 88

C. Job Aid 3 - Sample Initial Interview Questions - Principal

Residence ..................................................................................... 89

D. Resources for Real Estate Foreclosures and Cancellation of

Debt Income ................................................................................. 90

7

I. Overview

(1) This audit technique guide discusses the tax consequences for real estate

property that is disposed of through foreclosure, short sale, deed in lieu of

foreclosure, and abandonments. Although, the term foreclosure is used

throughout this document, the tax treatment also applies to short sales, deed in

lieu of foreclosures, and abandonments. A discussion is also devoted to

cancellation of debt income exclusions that are most commonly applicable to

these types of dispositions and community property considerations. This guide

primarily focuses on tax consequences for individual taxpayers. Keep in mind

that the examples presented in this Audit Technique Guide are general

examples and should not solely be relied upon for every situation as each fact

pattern may change the tax consequences.

A. Background / History

(1) According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s December 2013 Housing Scorecard,

3.6 million cumulative completed foreclosures occurred from April 2009 through

October 2013. This number includes investment, second home, and jumbo

mortgage properties (high-end properties).

(2) Many taxpayers were unaware that even though their lender foreclosed on their

properties, there could be tax consequences and the lender could legally

pursue collection of any outstanding deficiency. In 2009, the government

stepped in to help distressed homeowners and implemented various assistance

programs, such as the Making Home Affordable Program, as a strategy to help

homeowners avoid foreclosure, stabilize the country's housing market, and

improve the nation's economy. Federal and State governments have filed

numerous lawsuits against lending institutions for unfair and/or fraudulent

practices. As a result, mortgage lenders have implemented changes.

(3) IRC § 61(a)(11), IRC § 61(a)(12) prior to January 1, 2019, provides that gross

income includes income from discharge of indebtedness. When money is

borrowed, the loan proceeds are not included in income because an obligation

to repay the lender exists. Generally, when debt for which a taxpayer is

personally liable is subsequently forgiven, the amount received as loan

proceeds is reportable as income because an obligation to repay the lender no

longer exists, which results in an economic benefit to the taxpayer.

(4) Under IRC § 108(a) taxpayers may exclude discharged debt if the taxpayer is

bankrupt, insolvent, the discharged debt is qualified farm indebtedness, the

discharged debt is qualified real property business indebtedness, or if the

discharged debt is qualified principal residence indebtedness. Form 982,

Reduction of Tax Attributes Due to Discharge of Indebtedness (And Section

8

1082 Basis Adjustment), is completed to report the exclusion and the reduction

of certain tax attributes either dollar for dollar or 33 1/3 cents per dollar.

(5) PLR 8918016, 1989 WL 595222, states that, “[A]ccording to legislative history

of the Bankruptcy Tax Act of 1979, the purpose of IRC §108 is to accommodate

both tax and bankruptcy policies. Due to the Supreme Court’s decision in

United States v. Kirby Lumber Co., 284 U.S. 1 (1931), tax policy requires

debtors to include in gross income the amount of debt they are no longer

required to repay, including debts discharged in bankruptcy.”

(6) The Mortgage Forgiveness Debt Relief Act of 2007 allowed qualifying taxpayers

to exclude debt discharged as income from a borrower’s principal residence.

Consequently, IRC § 108(a)(1)(E) was added to the Internal Revenue Code.

B. Exceptions

(1) Gifts, deductible debt, and purchase price reduction are exceptions to IRC §

61(a)(11) where discharged debt is not taxable. These exceptions apply before

the exclusions under IRC § 108(a)(1) and do not require a reduction of tax

attributes.

B.1. Gifts

(1) If forgiveness of the debt is a gift, then generally, it is not considered income.

However, the donor may be required to file a gift tax return.

B.2. Deductible Debt (Lost Deduction)

(1) If the payment of the debt would result in a deduction, then the cancellation of

the debt is not included in gross income. For example, Marvin was discharged

of $50,000 ($20,000 principal and $30,000 interest) of mortgage debt. If Marvin

would have made the mortgage payments, he may have been able to deduct

the $30,000 as mortgage interest expense on his tax return. Since Marvin did

not make his mortgage payments, the $30,000 is a lost deduction. Thus,

Marvin’s cancellation of debt income is $20,000.

B.3. Purchase Price Reduction

(1) If the seller reduces the amount of debt owed for property purchased, the

reduction generally does not result in cancellation of debt income. The

reduction of the debt is treated as a purchase price adjustment and reduces the

property’s basis. In comparison, if a bank or financial institution that holds the

mortgage note reduces or modifies the balance of the loan, the debt restructure

is treated as a loan modification and is not considered a purchase price

reduction.

9

(2) For example, Jane purchased a residence from Jamie and obtains a mortgage

loan from a third party, Adam. During escrow, Jamie decides to reduce the

purchase price of the property due to a problem discovered during the house

inspection. Jamie’s reduction of the purchase price is considered a purchase

price reduction and not cancellation of debt.

C. Relevant Terms

(1) Cancellation of Debt Income (CODI) – Also known as cancellation of

indebtedness income (COII) – If a lender forgives a borrower of all or part of an

outstanding debt owed, the borrower is considered to have received a benefit

that has put him/her into a better financial position.

(2) The amount of the benefit must be reported as income received under

IRC § 61(a)(11), unless the taxpayer qualifies for an income exclusion under

IRC § 108.

(3) Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure – The borrower returns the property back to the

lender in full satisfaction of the mortgaged outstanding debt balance upon an

agreement by the lender. The principal advantage to the borrower is that it

immediately releases him/her from most or all of the personal indebtedness

associated with the defaulted loan.

(4) Final Closing Statement or HUD-1 - This form is used as a statement of actual

charges and adjustments paid by the borrower and the seller. The concept is

similar to that of the T- account where all incoming and outgoing amounts of the

real estate transaction are listed. Both parties receive a copy of this statement

before or at closing. A sample of the Settlement Statement (HUD-1) can be

found on the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development

website.

(5) Foreclosure – A legal procedure by which mortgaged real estate property is

sold by the lender in full or partial satisfaction of the mortgage debt. For

example, if the borrower fails to pay the monthly mortgage payments, the lender

takes the property back and sells it to recover some or all of the debt. If

proceeds from the sale fail to pay recourse debt in full, the lender may obtain a

deficiency judgment in court to recover the outstanding balance. The

foreclosure proceeding and whether the lender is able to obtain a deficiency

judgment is determined by the law of the state where the property is located.

(6) Nonrecourse Debt – The borrower is not personally liable and repossession of

the mortgaged property, for example, will generally satisfy the outstanding debt.

(7) Recourse Debt – The borrower is personally liable for the loan. Meaning, the

lender can obtain a deficiency judgment against the borrower in court for any

outstanding balance that is not satisfied through a foreclosure sale. State law of

10

where the property is located governs whether the lender is able to obtain a

deficiency judgment.

(8) Relocation Assistance - Some taxpayers qualify for relocation funds to assist

with moving expenses. These programs are offered through federal, state and

local government, and lenders. The taxpayer may receive monies for their

principal residence, rental property and investment property. These funds are

taxable and included in the gain/loss computation.

(9) Short sale - A sale of mortgaged real estate property in which the proceeds

from selling the property will fall short of the total balance owed by the borrower.

Short sale agreements do not necessarily release the borrower from their

obligation to repay any loan deficiency unless specifically agreed to between

the lender and property owner and governing state law.

D. Key Tax Issues

(1) Foreclosure issues may not be as cut and dry as Schedule C advertising

expenses and are very factual, circumstantial and specific. One fact or

circumstance could change the result of how the foreclosure is reported on the

return. Questions should be asked and documents gathered that will address

the issues of whether the foreclosure, short sale or deed in lieu of foreclosure

resulted in a recognized gain or loss and cancellation of indebtedness income,

and how these amounts should be reported on the taxpayer’s tax return. Other

issues arise when a taxpayer excludes cancellation of debt income. Chapter 11,

Audit Strategies and Case File Documentation, includes a discussion on case

file documentation, job aids, resources, and contact information. For example,

Job Aid 2 - Sample Information Document Request, is a sample information

document request (IDR) with requests for general and loan modification

information. Job Aid 3 - Sample Initial Interview Questions - Principal

Residence, contains sample interview questions for the disposition of a principal

residence.

(2) Foreclosures, short sales and deeds in lieu of foreclosure are considered

dispositions. Keep in mind that if a taxpayer is involved in a short sale he/she

will know the date the property was sold and the sales amount, because he/she

will work closely with the real estate agent and lender during the short sale

process. The final closing statement will show the amount of the loan that will

be satisfied by the sale. The total loan balance will conceptually be equal to the

amount on the final closing statement and the amount of debt forgiven. In

comparison, a taxpayer does not become aware of the identifying information

regarding a disposition through a foreclosure, until after the lender sells the

property and generally issues a Form 1099-C, Cancellation of Debt.

(3) Once a lender repossesses real estate property through a foreclosure or the

lender becomes aware that the property owner abandoned the property, the

lender should issue the taxpayer a Form 1099-A, Acquisition or Abandonment

11

of Secured Property. If the lender also forgives or cancels part or all of the

outstanding debt, a Form 1099-C should be issued to the taxpayer. If the lender

forecloses on the property and forgives the debt within the same year, then the

lender is only obligated to issue a Form 1099-C for debt canceled of $600 or

more. The taxpayer should contact the bank if the information is incorrect so

that corrected forms are issued.

(4) Confusion arises when a taxpayer receives a Form 1099-A in one year and a

Form 1099-C in a subsequent year for a recourse note. A foreclosure is a

disposition within the meaning of IRC § 1001 (Helvering v. Hammel, 311 U.S.

504 (1941)). The foreclosure sale ends the mortgagor’s ownership in the

property, and at that time, the gain or loss from the sale or other disposition of

the mortgaged property should be determined (Helvering v. Hammel, 311 U.S.

504 (1941)). Refer to the discussion in Chapter 2, Type of Debt - Nonrecourse

and Recourse Debt, for additional information.

(5) The Service has observed that lenders may issue Forms 1099 only for the

primary loan. All property loans should be considered in the determination of

any cancellation of debt income as well as gains or losses. Therefore, it is

important to ask the taxpayer questions about the events leading up to and after

the disposition. To identify all loans associated with the disposed property,

search property records and IRPTR, or review prior years’ returns for mortgage

interest. Sometimes a lender may erroneously fail to issue the taxpayer a Form

1099-C. Facts and circumstances will dictate when or if any outstanding debt

has been discharged, absent the issuance of a Form 1099-C. Under IRC §

7491(a)(1), under certain circumstances, in any court proceeding, the burden

shifts to the IRS to prove that the taxpayer received cancellation of

indebtedness income if the taxpayer provides creditable evidence with respect

to any factual issue relevant to ascertaining the income tax liability of the

taxpayer. Refer to the discussion in Chapter 7, Form 1099-A and Form 1099-C,

for additional information.

(6) Consideration of whether the lender has pursued collection activity and the

state where the property is located are two primary factors. Each state has its

own foreclosure legal laws and time frames that a lender must pursue collection

activities. Absent a Form 1099-C, it is reasonable to conclude that the taxpayer

was forgiven the outstanding balance if the lender has not pursued collection

activity in accordance with the state law of the location of the property. For

example, if a foreclosure is completed by non-judicial means in some states,

the lender is precluded from pursuing a deficiency judgment for the outstanding

balance.

(7) Some states, listed below, have anti-deficiency laws which prohibit a lender

from pursuing a deficiency judgment against the borrower under certain

circumstances. Although, these states are identified as Anti-Deficiency states, it

is important to note that each of these states has its own rules and the anti-

12

deficiency rules are not applied in the same manner. It is important to

understand the state law where the property is located as it could make a

difference in the amount of income includable in taxable income or excludable

from taxable income. Anti-deficiency/nonrecourse states are identified below:

• Alaska

• Arizona

• California

• Connecticut

• Idaho

• Minnesota

• North Carolina

• North Dakota

• Texas

• Utah

• Washington

(8) It is advised to seek assistance from local Counsel for specific state questions

regarding foreclosures. Refer to the Local Law Section in IRM 5.17, Legal

Reference Guide for Revenue Officers, for more information.

(9) In general, if indebtedness is canceled or forgiven, the amount canceled or

forgiven must be included in gross income. If CODI is excluded from income, it

generally will postpone the income tax liability on cancellation of indebtedness

through the reduction of tax attributes.

II. Type of Debt - Nonrecourse and Recourse Debt

(1) As defined earlier, a loan is nonrecourse if the taxpayer is not personally liable

and the bank cannot pursue the taxpayer for any outstanding balance after the

property is foreclosed. The loan is recourse if the taxpayer was personally liable

for repayment of the loan and the bank has the right to pursue collection of all

or part of the outstanding balance after the foreclosure. The lender may have

indicated on Form 1099 whether the taxpayer was personally liable or not.

(2) Consultation with local Counsel regarding state law may assist in identification

of the type of loan. Each loan type has different tax consequences. Although, a

13

taxpayer no longer owns their foreclosed property, a reportable gain or taxable

CODI from the disposition could result because foreclosures, short sales, and

deeds in lieu of foreclosure are treated as taxable dispositions.

(3) The computation of gain or loss from the sale or other disposition of property is

located in IRC § 1001. The gain is the excess of the amount realized over the

adjusted basis. The loss is the excess of the adjusted basis over the amount

realized.

A. Nonrecourse Debt

(1) A loan is nonrecourse if the taxpayer is not personally liable and the bank

cannot pursue the taxpayer for any outstanding balance after the property is

foreclosed. The borrower is not personally liable and repossession of the

mortgaged property, for example, will generally satisfy the outstanding debt.

Generally, there is no CODI from foreclosure of property with nonrecourse debt.

However, situations may exist where a taxpayer will have CODI from

nonrecourse debt. Refer to Example 5, which is an example of CODI from

nonrecourse debt.

(2) Nonrecourse debt generally has one tax consequence to consider and that is

whether a recognized gain or loss from the disposition exists. The gain/loss

calculation is the amount realized less the adjusted basis. For nonrecourse

debt, the amount realized is the greater of the outstanding debt of all loans

immediately before the foreclosure or fair market value of the property plus the

proceeds received from the foreclosure (e.g., relocation payment from the

lender). The adjusted basis immediately before the foreclosure is subtracted

from the amount realized to determine the gain or loss.

(3) IRC § 7701(g) states that the sales price is the greater of the FMV or the

outstanding loan balance for nonrecourse loans to determine the gain or loss.

(4) In Commissioner v. Tufts, 461 U.S. 300 (1983), the Supreme Court held that

when a taxpayer “sells or disposes of property encumbered by a nonrecourse

obligation exceeding the fair market value of the property sold, as in this case,

the Commissioner may require him to include in the “amount realized” the

outstanding amount of the obligation; the fair market value of the property is

irrelevant to this calculation.” The Court reasoned that because a nonrecourse

note is treated as a true debt upon inception (so that the loan proceeds are not

taken into income at that time), a taxpayer is bound to treat the nonrecourse

note as a true debt when the taxpayer is discharged from the liability upon

disposition of the collateral, in spite of the lesser fair market value of the

collateral.

14

A.1. Nonrecourse Debt Examples

(1) Example 1. Maxine paid $200,000 for her second home. She put $15,000 down

and borrowed the remaining $185,000 from a bank. Maxine is not personally

liable for the loan, but pledges the house as security. The bank foreclosed on

the mortgage because Maxine stopped making payments. When the bank

foreclosed on the loan, the balance due was $180,000, the fair market value of

the house was $170,000, and Maxine’s adjusted basis was $175,000 due to a

casualty loss she had deducted. Maxine has a gain of $5,000 ($180,000

outstanding debt minus $175,000 adjusted basis) from the foreclosure.

(2) The lender’s foreclosure on property secured by nonrecourse debt that is

greater than the FMV of the property does not result in cancellation of debt

income. The entire amount of the nonrecourse debt is treated as the amount

realized. As such, Maxine recognized no CODI upon the foreclosure, but

realized $180,000, the outstanding debt balance immediately before the

foreclosure. Her gain is the difference between the loan balance of $180,000

and the adjusted basis of $175,000. Maxine has a $5,000 recognized gain from

the foreclosure of her second home. The disposition is reported on Form 8949,

Sales and Other Dispositions of Capital Assets, and Schedule D, Capital Gains

and Losses.

(3) Generally, there is no cancellation of debt income from foreclosure of property

when nonrecourse debt secures the property, because repossession of the

mortgaged property will satisfy the outstanding debt. The lender’s foreclosure

on property secured by nonrecourse debt that is greater than the FMV of the

property does not result in cancellation of debt income. The entire amount of

the nonrecourse debt is treated as the amount realized.

(4) However, in certain situations, the discharge of nonrecourse debt will result in

CODI. Revenue Ruling 91-31, 1991-1 C.B. 19 provides that the reduction of the

principal amount of an undersecured nonrecourse debt (nonrecourse debt

greater than the fair market value of the property) results in CODI. For example,

a reduction in the loan balance through a loan modification will result in CODI

when nonrecourse debt exceeds fair market value of the property.

(5) Confusion exists as to the year that the disposition should be reported when the

lender repossesses property and then sells it in a subsequent year. If the note

that secured the property was nonrecourse, the disposition is reported in the

year of repossession.

(6) Example 2. Walter paid $580,250 for his second home. He paid $30,000 down

and borrowed the remaining $550,250 from a bank. Walter is not personally

liable for the loan, but pledges the house as security. When the fair market

value of the property dropped to $400,000 and the loan balance was $535,698,

15

the bank agreed to modify his loan and reduced the principal balance by

$52,435.

(7) Walter did not qualify to exclude the cancellation of debt income from gross

income under IRC § 108. Therefore, Walter would report $52,435 as other

income on Form 1040 for the discharged nonrecourse debt.

B. Recourse Debt

(1) The loan is recourse if the taxpayer was personally liable for repayment of the

loan and the bank has the right to pursue collection of all or part of the

outstanding balance after the foreclosure. Recourse debt has three different

potential tax consequences which are (1) CODI, (2) gain/loss from the

disposition, and (3) the reduction of tax attributes if CODI is excluded from

income.

(2) The first calculation is to determine the amount of cancellation of debt income.

Cancellation of debt income is determined by the outstanding debt balance

immediately before the foreclosure (minus debt liable after the foreclosure)

minus the fair market value of the property equals the cancellation of debt

income.

(3) Cancellation of debt income may be excluded if the taxpayer qualifies under

IRC § 108. Form 982 is used to report the exclusion and any reduction of

certain tax attributes.

(4) Taxable cancellation of debt income is reported as:

• Non-business Debt – Form 1040 as other income.

• Sole Proprietorship – Schedule C or F as other income, if the debt is

related to a sole proprietorship nonfarm or farm business.

• Non-Farm Rental Activity – Schedule E as other rental income, if the debt

is related toa nonfarm rental of real property.

• Farm Rental Activity – Form 4835 to report rental income based on crops

or livestock produced by a tenant.

(5) In general, if taxable income (including CODI) is derived from a trade or

business and is reported on a Schedule C or F, then it is self-employment

income and it will be subject to self-employment tax. If an exception applies to

exclude CODI from gross income, the CODI is also not self-employment income

subject to self-employment tax. Self-employment income means the “net

earnings from self-employment derived by an individual” IRC § 1402(b). Net

earnings from self-employment is defined as “the gross income derived by an

16

individual from any trade or business carried on by such individual, less the

deductions allowed by this subtitle which are attributable to such trade or

business, plus his distributive share (whether or not distributed) of income or

loss described in IRC § 702(a)(8) from any trade or business carried on by a

partnership of which he is a member” IRC § 1402(a) and Treas. Reg. §

1.1402(a)-1.

(6) The second tax consequence for a recourse note is the calculation of the gain

or loss from the foreclosure sale. The gain or loss is calculated as the amount

realized plus any proceeds received from the foreclosure (e.g., relocation

payment from the lender) minus the adjusted basis of the property immediately

before the foreclosure sale. The amount realized is the lesser of the fair market

value of the property or outstanding debt balance.

(7) The fair market value of a property may be in question during an examination.

That is because the sales price of the property is generally determined to be the

fair market value of the property. This amount may be different from the amount

reported on Form 1099-A. In Frazier v. Commissioner 111 T.C. 243, 246 (1998)

the court stated, “Absent clear and convincing proof to the contrary, the sale

price of property at a foreclosure sale is presumed to be its fair market value.”

See Community Bank v. Commissioner, 79 T.C. 789, 792 (1982), affd. 819 F.2d

940 (9th Cir.1987).

(8) The third potential tax consequence of a recourse note is the reduction of tax

attributes when cancellation of debt income is excluded from gross income.

Generally, tax attributes are reduced by the amount of CODI excluded from

income. Reduction of tax attributes is discussed later under Reduction of Tax

Attributes in Chapter 4.

(9) Confusion exists as to the year that the disposition should be reported when the

lender repossesses property and then sells it in a subsequent year. If the note

that secured the property was recourse, the disposition is reported in the year of

the foreclosure sale.

(10) Property which secures a taxpayer's recourse obligation is not worthless prior to

foreclosure. Commissioner v. Green, 126 F. 2d 70, 72 (3d Cir. 1942) (“where,

as here, the taxpayer is liable for the debt, interest and taxes by virtue of the

mortgage or the bond thereby secured, the property continues, until foreclosure

sale, to have some value which, when determined by the sale, bears directly

upon the extent of the owner's liability for a deficiency judgment.”). Likewise,

property which secures a taxpayer's recourse obligation may not be considered

abandoned for purposes of a loss deduction prior to foreclosure. Daily v.

Commissioner, 81 T.C. 161 (1983) (an attempt to abandon property subject to

recourse debt does not result in a deductible loss), aff'd, Daily v Commissioner,

742 F.2d 1461 (9th Cir. 1984). Once the year of disposition is identified and the

17

type of debt is identified that secured the real estate property, the computation

of the gain or loss and any CODI can be made.

B.1. Recourse Debt Examples

(1) Example 3. Marcus bought his second home for $400,000 in year 1. He paid

$30,000 down and borrowed the remaining $370,000 from a bank. Marcus is

personally liable for the loan and the house is pledged as security for the loan.

Marcus lost his job several years later and the bank declined his requests for a

loan modification. Although, Marcus found another job, he earned less and was

unable to make the mortgage payments and the bank ultimately foreclosed on

the home in year 12. Marcus moved out of the home in year 12.

(2) The recourse debt balance before the foreclosure was $350,000. In the same

year, the bank sold the property for $250,000 to a third party. After the

foreclosure sale, the bank forgave $60,000 of the $100,000 debt in excess of

the FMV ($350,000 minus $250,000) and Marcus remained liable for the

$40,000 balance. He did not qualify for any of the exclusions in IRC § 108(a)(1).

(3) In year 12, Marcus has cancellation of debt income of $60,000 ($350,000 debt

balance immediately before the foreclosure minus $40,000 amount personally

liable immediately after the foreclosure sale minus $250,000 FMV of the

property). Under the circumstances, Marcus has other income of $60,000 from

the canceled debt. His nondeductible loss is $150,000 ($250,000 FMV of the

property minus $400,000 adjusted basis of the property).

(4) Marcus would file Form 982 to report the CODI exclusion and complete Part I

for discharge of qualified principal residence indebtedness. Marcus should also

report the foreclosure on Form 8949, Sales and Other Dispositions of Capital

Assets as a nondeductible loss. For more details, see Nondeductible Losses in

the instructions to Schedule D, Capital Gains and Losses.

(5) Example 4. Jimmy took out a recourse loan for $700,000 to purchase an office

building to expand his sole proprietorship realty business. Three years later,

through a loan modification, the bank forgave $78,000 of the loan balance when

the FMV of the property was $600,000. Jimmy would report $78,000 on

Schedule C as other income if he did not qualify to exclude some or the entire

amount of CODI under IRC § 108.

C. Gain and Loss Computation and Cancellation of Debt Income

(1) The computation of gain or loss from the sale or other disposition of property is

located in IRC § 1001. The gain is the excess of the amount realized over the

adjusted basis. The loss is the excess of the adjusted basis over the amount

realized.

18

(2) The amount realized is defined in IRC § 1001(b) as money received plus the

fair market value of the property received (other than money). As discussed

later, the amount realized for nonrecourse notes is the greater of the fair market

value (FMV) of the property or the outstanding loan amount. The amount

realized for recourse notes is the lesser of the fair market value of the property

or the outstanding loan amount. Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-2 discusses the gain or

loss when there is a discharge of liabilities. Examples of dispositions for

nonrecourse and recourse notes are under Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-2(c).

(3) Confusion exists as to the year that the disposition should be reported when the

lender repossesses property and then sells it in a subsequent year. If the note

that secured the property was nonrecourse, the disposition is reported in the

year of repossession. If the note that secured the property was recourse, the

disposition is reported in the year of the foreclosure sale.

(4) Taxable consequences of nonrecourse and recourse debt are explained below.

The first step is to identify whether the debt is nonrecourse or recourse debt.

• Nonrecourse - If the debt is nonrecourse, there is generally one tax

consequence to consider and that is whether a recognized gain or loss

from the disposition exists.

• Recourse - If the debt is recourse, recourse debt has three different

potential tax consequences which are (1) Cancellation of debt income, (2)

gain/loss from the disposition, and (3) the reduction of tax attributes if

CODI is excluded from income.

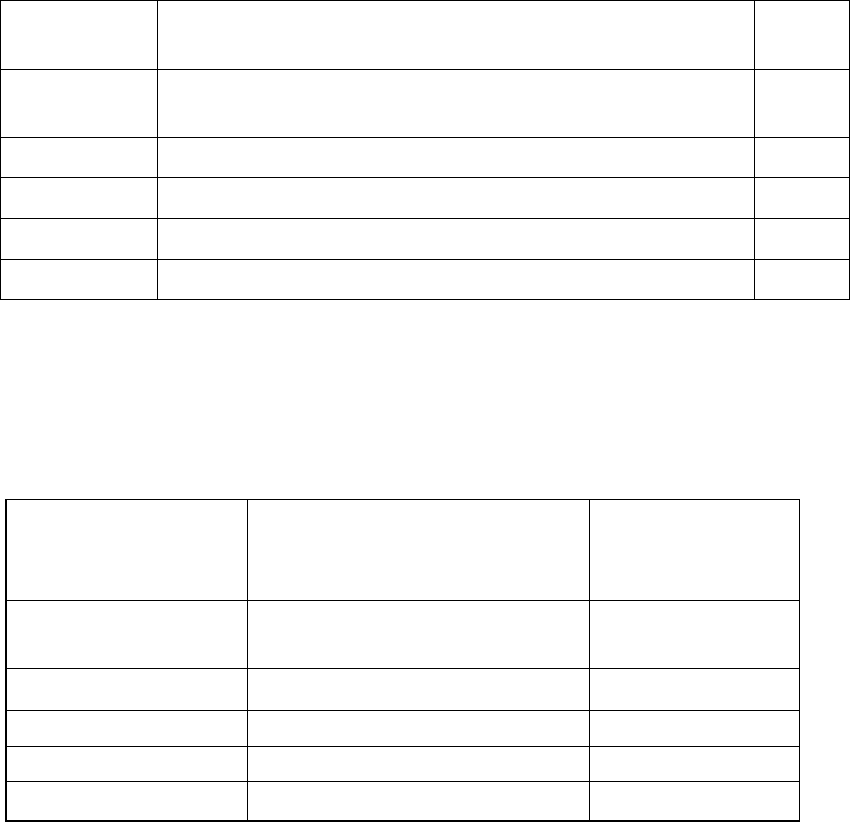

D. Analysis of Disposition of Property Secured by Nonrecourse or

Recourse Debt

(1) The primary difference between nonrecourse and recourse debt is the timing

and amount of any potential taxable income from the disposition and

cancellation of debt income demonstrated in the following Table 1, Analysis of

Disposition of Property. For this analysis, the outstanding loan balance is

$300,000, the fair market value of the property is $265,000, and the adjusted

basis is $280,000. The cancellation of debt income is $35,000 ($300,000

outstanding loan balance minus $265,000).

19

(2) Table 1. Analysis of Disposition of Property

Description

Nonrecourse

Recourse

Amount realized

$300,000

$265,000

Minus adjusted basis

280,000

280,000

Equals gain/(loss)

$20,000

(15,000)

Add cancellation of debt income

35,000

Equals net gain on disposition

$20,000

(3) The nonrecourse note results in a gain of $20,000 ($300,000 amount realized

minus $280,000 adjusted basis). Whereas, the recourse note results in a

disposition loss of $15,000 ($265,000 amount realized minus $280,000

adjusted basis) plus $35,000 of cancellation of debt income resulting in a net

gain of $20,000. The overall tax consequence for both notes is a gain of

$20,000. However, the $35,000 cancellation of debt income can be deferred

through the reduction of tax attributes if the taxpayer qualifies to exclude the

cancellation of debt income under IRC § 108.

III. Income from Discharge of Indebtedness and Items Specifically

Excluded from Gross Income

(1) IRC § 61(a)(11) provides that gross income includes income from discharge of

indebtedness. When money is borrowed, the loan proceeds are not included in

income because an obligation to repay the lender exists. Generally, when debt

for which a taxpayer is personally liable is subsequently forgiven, the amount

received as loan proceeds is reportable as income because an obligation to

repay the lender no longer exists, which results in an economic benefit to the

taxpayer.

(2) As stated earlier, a foreclosure is a taxable disposition which may result in

recognized CODI and recognized gain. However, CODI can be excluded if the

taxpayer qualifies under IRC § 108. Keep in mind that the exclusions under IRC

§ 108 do not apply to the amount of gain recognized from a foreclosure, short

sale, or deed in lieu of foreclosure. Recognized gain and CODI are two

separate calculations. A taxpayer may exclude CODI under IRC § 108(a)(1) if:

• A. The discharge occurs in a bankruptcy case,

• B. The discharge occurs when the taxpayer is insolvent,

• C. The discharged indebtedness is qualified farm indebtedness,

20

• D. The discharged indebtedness is qualified real property business

indebtedness (valid election), or

• E. The discharged indebtedness is qualified principal residence

indebtedness.

(3) IRC § 108(a)(2) prescribes the coordination of the exclusions and is

summarized in Table 2, Order and Coordination of Exclusions. Bankruptcy

takes precedence over all other exclusions. An insolvent taxpayer would first

look to whether his/her situation qualified under the bankruptcy exclusion. If

he/she did not qualify then, the insolvency exclusion would be considered. A

farmer would first look to whether his/her situation qualified under the

bankruptcy exclusion, then insolvency, then the farm exclusion. A taxpayer who

qualified under the real property business exclusion, would first look to whether

his/her situation qualified under the bankruptcy exclusion, then insolvency, then

the real property business exclusion. A taxpayer who qualified under the

principal residence exclusion, would first look to whether his/her situation

qualified under the bankruptcy exclusion, then the principal residence exclusion.

A taxpayer may make an election to apply the insolvency exclusion instead of

the principal residence exclusion.

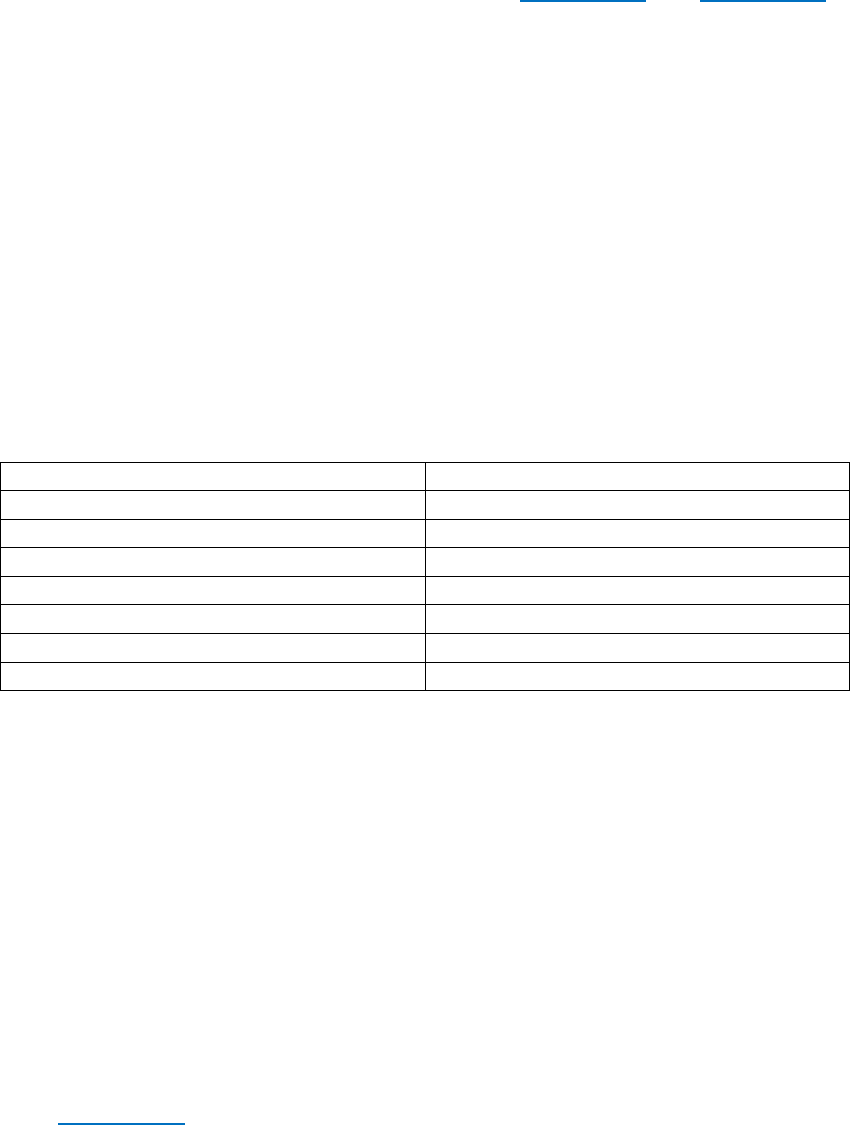

(4) Table 2. Order and Coordination of Exclusions

IRC 108 Exclusions

1

2

3

Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy

Insolvency

Bankruptcy

Insolvency

Qualified Farm

Indebtedness

Bankruptcy Insolvency Farm

Qualified Real

Property Business

Bankruptcy Insolvency Business

Qualified Principal

Residence

Bankruptcy Principal

Residence (or

election to apply

insolvency

instead)

Insolvency

(5) If canceled debt is excluded from income under one or more of these

provisions, generally, tax attributes are reduced by the amount excluded (but

not below zero). This is discussed later under Reduction of Tax Attributes in

Chapter 4. These exclusions do not apply to any gain realized from foreclosure

or short sale or deed in lieu of foreclosure.

21

(6) A discussion of the exclusions follow. Please note that this guide will not cover

qualified farm indebtedness in detail. Refer to Publication 4681, Canceled

Debts, Foreclosures, Repossessions and Abandonments (for Individuals), and

Publication 225, Farmer’s Tax Guide, for more information.

A. Bankruptcy

(1) The general underlying principle of bankruptcy is to provide a debtor an avenue

to pay what the debtor can afford while receiving forgiveness for debt that

cannot be satisfied. For example, in a Chapter 7, Bankruptcy, a trustee takes

control of the debtor’s bankruptcy estate assets, liquidates nonexempt property,

and distributes the cash to creditors. Remaining unpaid debts are generally

discharged. After the trustee winds down the affairs, if any property remains,

the trustee will transfer the property back to the debtor. Refer to IRM 5.9,

Bankruptcy and Other Insolvencies, for additional information. IRM Exhibit

5.9.1-1 includes a glossary of common insolvency terms. Examiner

responsibilities are discussed in IRM 4.27.1, Bankruptcy, Examiner

Responsibilities and Procedures.

(2) IRC § 108(a)(1)(A) allows for cancellation of debt income to be excluded from

income where the debt was discharged in a bankruptcy case. However, merely

filing for bankruptcy does not meet this exclusion – the debt must have been

discharged during the course of the bankruptcy case. As discussed earlier, the

bankruptcy exclusion takes precedence over the other exclusions in IRC §

108(a)(1).

(3) Once you discover that a taxpayer has filed for bankruptcy, it is important that

you contact the bankruptcy coordinator in Technical Services who would be

able to provide information about the bankruptcy. It is important to know the

status of the bankruptcy, because it could affect how you proceed with the

case. If applicable, communicate with the Collection Officer assigned to the

case in a timely manner so that Collection is able to take appropriate action

within required timeframes.

A.1. Example

(1) Example 5 (Part I of Example 18, Chapter 4). Tara owed several creditors

and was no longer able to meet her financial obligations, as a result, she filed

for Chapter 7 bankruptcy and was granted a discharge of her recourse debt of

$174,678 in year 1. Tara excluded the $174,678 from taxable income on her

Form 1040 (year 1) tax return and attached Form 982 to report the exclusion

and amount. She checked line 1a to report that the discharge was in a title 11

case (bankruptcy) and entered $174,678 on line 2 of Form 982. Tara is also

required to reduce tax attributes. Refer to Example 18 for the attribute reduction

calculation.

22

A.2. Examination Consideration

(1) The bankruptcy exclusion is NOT an election. Although, Form 982 is used to

report the exclusion type, amount of CODI excluded from gross income, and the

tax attribute reduction, it is not required to be filed with a tax return for the

bankruptcy exclusion. Failure to attach a Form 982 to a tax return does not

prevent a taxpayer from excluding cancellation of debt income under the

bankruptcy exclusion. As such, a taxpayer can present documentary evidence

for consideration during an examination. An examiner should gather all

necessary documents and develop relevant facts to determine whether a

taxpayer meets the bankruptcy exclusion.

B. Insolvency

(1) IRC § 108(a)(1)(B) provides that gross income does not include cancellation of

debt income if the discharge occurs when the taxpayer is insolvent. This

exclusion takes precedence over the qualified farm and qualified real property

business exclusions.

(2) IRC § 108(d)(3) defines insolvent as the excess of liabilities over the fair market

value of assets, immediately before the discharge. A taxpayer can exclude

cancellation of debt income up to the amount of insolvency per IRC § 108(a)(3).

The CODI amount excluded cannot exceed the amount by which a taxpayer is

insolvent. A spouse does not realize CODI from their spouse’s discharge of

debt.

B.1. Insolvency Calculation

(1) Both tangible and intangible assets are included in the calculations. Assets also

include exempt assets as defined by state law. The separate assets of a

debtor's spouse are not included in determining the extent of insolvency of the

debtor. For more information, refer to Chapter 8, Community and Common Law

Property, discussed later.

(2) Both recourse and nonrecourse liabilities are included in the insolvency

computation, while contingent liabilities are not included. Accrued but unpaid

interest expenses and income taxes that have become an obligation of the

debtor, along with other fixed and certain claims are considered liabilities of the

debtor. The separate liabilities of a debtor's spouse are not included in the

calculation of the debtor. Refer to Chapter 8, Community and Common Law

Property Systems discussed later for more information.

(3) In Shepherd et ux. v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2012-212, the court decided

that the taxpayers did not meet their burden to prove the fair market value of

two properties at the time of discharged debt and the taxpayers failed to include

23

at least a percentage (amount he was able to withdraw), of the husband’s

retirement account, as an asset in their insolvency calculation.

(4) Job Aid 1 - Insolvency Worksheet, included in Chapter 11, Audit Strategies and

Case File Documentation, can be used to determine the extent of insolvency.

The worksheet is also located in Publication 4681.

B.2. Examples

(1) Example 6 (Part I of Example 20, Chapter 4). Ashley was unable to pay her

recourse mortgage for her second home after her divorce. She entered into a

deed in lieu of foreclosure agreement with the lender on October 1 of year 1

and simultaneously forgiven of the outstanding debt. The bank subsequently

issued a Form 1099-C for $50,000 discharged debt.

(2) Ashley's total liabilities immediately before the cancellation were $756,589 and

the FMV of her total assets immediately before the cancellation were $726,329.

In this case, Ashley is insolvent to the extent of $30,260 ($756,589 total

liabilities minus $726,329 FMV of her total assets) immediately before the

cancellation. Ashley can exclude only $30,260 of the $50,000 canceled debt

from income under the insolvency exclusion. IRC § 108(a)(3). Ashley would

report $19,740 ($50,000 debt forgiven minus $30,260 extent of insolvency) of

the CODI as other income on her Form 1040. She would also attach Form 982

to her tax return, and check line 1b and enter $30,260 on line 2. Ashley would

also complete Form 982 Part II to reduce her tax attributes as illustrated in

Example 20.

(3) What happens if a taxpayer is partially discharged of a nonrecourse debt when

applying IRC §108(d)(3), insolvency exclusion? Revenue Ruling 92-53, 1992-2

C.B. 48 addresses the treatment of nonrecourse indebtedness when applying

the insolvency exclusion. The ruling states that, “…the amount by which a

nonrecourse debt exceeds the fair market value of the property securing the

debt is taken into account in determining whether, and to what extent, a

taxpayer is insolvent within the meaning of section 108(d)(3) of the Code, but

only to the extent that the excess nonrecourse debt is discharged.” Excess

nonrecourse debt is the amount of nonrecourse debt that exceeds the fair

market value of the property that the debt secures. Example 7 and Example 8

demonstrate the application of this Revenue Ruling.

(4) Example 7. Samantha entered into a loan modification and the lender agreed

to reduce the principal balance of the nonrecourse loan from $195,000 to

$175,000 when the value of the home declined. At the time of the loan

modification, the fair market value of the home was $150,000. Samantha’s

other liabilities consisted of recourse debt of $80,000 and nonrecourse debt

(limited to the FMV of the assets that secures the debt) of $30,000 and the FMV

24

of other assets was $70,000. Three years later the lender foreclosed on the

property due to Samantha’s failure to pay her monthly mortgage payments.

(5) In this situation, $20,000 ($195,000 original mortgage minus $175,000 new

mortgage) of Samantha’s $45,000 ($195,000 original mortgage minus $150,000

FMV of the property) excess nonrecourse debt is discharged. Only the portion

of the excess nonrecourse debt that is discharged is taken into account in

determining to what extent Samantha is insolvent.

(6) Samantha’s total liabilities are $280,000 ($150,000 nonrecourse debt limited to

FMV of the home plus $20,000 excess nonrecourse debt limited to discharged

amount plus $110,000 other recourse and nonrecourse liabilities). Nonrecourse

debt ($175,000) is limited to the fair market value ($150,000) of the asset that

secures the loan, because the taxpayer is not personally liable and generally

not expected to pay any outstanding balance if the property is repossessed.

Samantha’s total assets right before the discharge are $220,000 ($150,000

FMV of the home plus $70,000 FMV of other assets).

(7) Samantha is insolvent by $60,000 ($280,000 total liabilities minus $220,000

total assets). Since the discharged amount of $20,000 is less than the extent

that Samantha is insolvent, the entire $20,000 can be excluded from income

under IRC §108(a)(1)(B).

(8) Example 8. Naomi entered into a loan modification and the lender agreed to

reduce the principal balance of the recourse loan from $195,000 to $175,000

when the value of the home declined. At the time of the loan modification, the

fair market value of the home was $150,000. Naomi’s other liabilities consisted

of recourse debt of $80,000 and nonrecourse debt (limited to the FMV of the

assets that secures the debt) of $30,000 and the FMV of other assets was

$70,000. Four years later, Naomi was unable to make her mortgage payments

and disposed of the property through a short sale.

(9) The amount discharged by the lender was $20,000 ($195,000 original mortgage

minus $175,000 new mortgage amount).

(10) Total liabilities right before the discharge was $305,000 ($195,000 recourse

debt plus $110,000 other recourse and nonrecourse liabilities). Nonrecourse

debt is limited to the fair market value of the asset that secures the loan,

because the taxpayer is not personally liable and not expected to pay any

outstanding balance if the property is repossessed.

(11) Total assets right before the discharge was $220,000 ($150,000 FMV of the

home plus $70,000 FMV of other assets).

(12) Naomi is insolvent by $85,000 ($305,000 total liabilities minus $220,000 total

assets). Since the discharged amount of $20,000 is less than the extent that

25

Naomi is insolvent, the entire $20,000 can be excluded from income under IRC

§ 108(a)(1)(B).

(13) In both examples (7 and 8), the taxpayers are able to exclude the entire

discharged debt. However, the treatment of the nonrecourse loans changed the

amount that the taxpayer is insolvent. In Example 7, a portion of Samantha’s

nonrecourse loan was discharged which resulted in an insolvency amount of

$60,000, due to the limitations applied to the nonrecourse loans. In contrast, in

Example 8, Naomi had discharged recourse debt which resulted in an

insolvency amount of $85,000, even though the mortgage loan amounts were

identical.

B.3. Examination Consideration

(1) Similar to the bankruptcy exclusion, the insolvency exclusion is NOT an

election. Although, Form 982 is used to report the exclusion type, amount of

CODI excluded from gross income, and the tax attribute reduction, it is not

required to be filed with a tax return for the insolvency exclusion. Failure to

attach a Form 982 to a tax return does not prevent a taxpayer from excluding

cancellation of debt income under the insolvency exclusion. Failure to attach a

Form 982 to a tax return does not prevent a taxpayer from excluding

cancellation of debt income from gross income. As such, a taxpayer can

present documentary evidence for consideration during an examination. An

examiner should gather all necessary documents and develop relevant facts to

determine whether a taxpayer meets the insolvency exclusion.

B.4. Audit Techniques

(1) Review the taxpayer’s insolvency calculation for reasonableness and request

supporting documentation as warranted.

(2) Look for any liabilities that might be associated with a corresponding asset. For

example, if a car loan is listed, the fair market value of the vehicle should be

listed under assets, unless the vehicle was repossessed.

(3) Generally, mortgage lenders will conduct an appraisal of the property during a

short sale process. Thus, a comparison of the fair market value on the Forms

1099-A and/or 1099-C with the taxpayer’s insolvency calculation can be done to

identify any differences. If you do identify any differences, request that the

taxpayer explain how they determined the fair market value for the property

especially, if the difference puts the taxpayer in an insolvent position.

(4) Taxpayers with high monthly income may in fact be insolvent. The insolvency

calculation considers the taxpayers overall financial position right before the

discharge of debt.

26

C. Qualified Farm Indebtedness

(1) Under IRC § 108(a)(1)(C) discharged qualified farm indebtedness after April 9,

1986, may be excluded from gross income. Generally, the exclusion for

qualified farm indebtedness allows a taxpayer who is in the business of farming

to reduce tax attributes in lieu of recognizing discharge of indebtedness income.

However, the taxpayer must first apply the rules for bankruptcy and then

insolvency under IRC § 108(a)(1)(A) and IRC § 108(a)(1)(B), respectively.

Taxpayers who have additional CODI after applying the insolvency exclusion

can use this exclusion for qualified farm debt.

(2) Under IRC § 108(g)(1), a discharge of debt qualifies for the qualified farm

indebtedness exclusion only if the discharge is by a creditor who is a qualified

person. A qualified person is defined in IRC § 108(g)(1)(B) as any federal, state

or local government or agency or instrumentality thereof and includes IRC §

49(a)(1)(D)(iv) an individual, organization, partnership, association, corporation,

etc. who regularly engaged in the business of lending money, which is not a

related person (as defined in IRC § 465(b)(3)(C)) with respect to the taxpayer.

(3) Two requirements must be met under IRC § 108(g)(2), for indebtedness to

qualify as qualified farm indebtedness. First, the indebtedness must have been

incurred directly in connection with the business of farming. Secondly, fifty

percent or more of the taxpayer's aggregate gross receipts for the three taxable

years preceding the taxable year of the discharge, must have been attributable

to the trade or business of farming.

(4) In addition, IRC § 108(g)(3) states that the excluded income cannot exceed the

sum of the adjusted tax attributes of the taxpayer plus the aggregate adjusted

bases of qualified property held by the taxpayer as of the beginning of the

taxable year following the taxable year of the discharge. Under IRC §

108(g)(3)(B), the adjusted tax attributes of the taxpayer are the sum of tax

attributes other than bases under IRC § 108(b)(2).

(5) The adjusted tax attributes are determined as the net operating loss (NOL) for

the year of discharge and any NOL carryover to the year of discharge plus any

net capital loss for the year of discharge and any capital loss carryover to the

year of discharge plus any passive activity loss carryover from the year of

discharge. Add three times the sum of any general business credit carryover to

or from the year of discharge and minimum tax credit available as of the

beginning of the following year of discharge and foreign tax credit carryover to

or from the year of discharge, and any passive activity credit carryover from the

year of discharge.

(6) IRC § 108(g)(3)(C), defines qualified property as any property used or held in a

trade or business or for the production of income. A taxpayer may elect on

Form 982 to treat real property held primarily for sale to customers as if it were

depreciable property. To the extent, the amount of the discharge exceeds the

27

sum of the relevant amounts, the taxpayer is required to recognize cancellation

of indebtedness income.

(7) More information about farming and agriculture issues can be found in

Publication 225, Farmer's Tax Guide.

C.1. Examples

(1) Example 9. Karla has been in the business of farming for the past five years

and is neither bankrupt nor insolvent. As of February 1, of year 1, she had total

debt of $140,000, total adjusted tax attributes of $80,000, and total adjusted

bases in qualified property as of January 1, of year 2, of $60,000. No other

exception or exclusion applied. Karla’s qualified creditors discharged the

$140,000 of debt in year 1 and subsequently issued a Form 1099-C. Karla can

exclude all $140,000 ($80,000 plus $60,000) of the canceled debt from income.

(2) Rev. Rul. 76-500, 1976-2 C.B. 254 states that “…the amount of the canceled

portion of a loan represents a replacement of a portion of a farmer's lost profits

and must be taken into account in computing net earnings from self-

employment for purposes of the tax on self-employment income”. Rev. Rul. 73-

408, 1973-2 C.B. 15, held that the canceled portion of an emergency loan

granted to a farmer by the Farmers Home Administration was includible in the

farmer's gross income. As such, taxable CODI is reported as other farming

income and is subject to self-employment tax.

(3) Example 10 (Part I of Example 23, Chapter 4). Chuck has been engaged in

the business of farming for the past four years and worked part-time as a

plumber for the past three years. Chuck’s creditors discharged $455,000 of debt

related to his farming business in year 1 and subsequently issued a Form 1099-

C. Chuck did not file for bankruptcy and he is solvent. Chuck qualified to

exclude CODI under the qualified farm indebtedness exclusion.

(4) Other facts include:

• His farming gross receipts for the preceding three years were $180,000

and gross receipts for the preceding three years from his plumbing

business were $7,500.

• Debt immediately before the discharge was $258,953.

• A net operating loss was $75,433 in year 1.

• Total adjusted bases in qualified property at the beginning of year 2 was

$350,000.

(5) Two requirements must be met under IRC § 108(g)(2), for indebtedness to

qualify as qualified farm indebtedness. First, the indebtedness must have been

28

incurred directly in connection with the business of farming. In this example, the

discharged debt related to Chuck’s farming business.

(6) Secondly, fifty percent or more of the taxpayer's aggregate gross receipts for

the three taxable years preceding the taxable year of the discharge, must have

been attributable to the trade or business of farming.

(7) Chuck’s aggregate farming gross receipts of $180,000 for the three preceding

years is more than fifty percent of aggregate gross income. Fifty percent of

$180,000 is $90,000 ($180,000 gross receipts multiplied by fifty percent).

(8) Further, the excluded income cannot exceed the sum of the adjusted tax

attributes of the taxpayer plus the aggregate adjusted bases of qualified

property held by the taxpayer as of the beginning of the taxable year following

the taxable year of the discharge.

(9) In this example, Chuck was discharged of $455,000 of debt. The amount

excluded is limited to $425,433 ($75,433 adjusted tax attribute (NOL) plus

$350,000 aggregate adjusted bases of qualified property). Cancellation of debt

income reportable in gross income was $29,567 ($455,000 discharged debt

minus $425,433 CODI limitation).

(10) Under IRC § 108(g)(3), excluded income is limited to $425,433. The remaining

$29,567 of canceled qualified farm debt should be included as farming income

subject to employment tax on the Form 1040, Schedule F for year 1, as other

income.

C.2. Examination Consideration

(1) The farm exclusion is NOT an election. Although, Form 982 is used to report

the exclusion type, amount of CODI excluded from gross income, and the tax

attribute reduction, it is not required to be filed with a tax return for the farm

exclusion. Failure to attach a Form 982 to a tax return for the farm exclusion

does not prevent a taxpayer from excluding cancellation of debt income from

gross income. As such, a taxpayer can present documentary evidence for

consideration during an examination. An examiner should gather all necessary

documents and develop relevant facts to determine whether a taxpayer meets

the farm exclusion.

D. Qualified Real Property Business Indebtedness

(1) A taxpayer (other than a C Corporation) may elect to exclude CODI from

discharged qualified real property business indebtedness under IRC §

108(a)(1)(D). An eligible taxpayer must make a valid election on a timely filed

return (including extensions), to exclude discharged qualified real property

business debt from income, by attaching Form 982 to the tax return. A taxpayer

may file a late election if an amended tax return is filed within six months of the

29

due date of the return (excluding extensions) under Treas. Reg. § 301.9100-2.

If an election is not made timely or with an amended return filed within six

months of the due of the return, a taxpayer must request permission to file a

late election.

(2) In PLR 201316009, 2013 WL 1699430, a taxpayer filed a timely individual tax

return in year 1. The taxpayer was a 50-percent partner in a LLC that received

cancellation of debt income related to qualified real property business

indebtedness. The LLC failed to identify the type of cancellation of debt income

and the individual’s tax preparer treated the CODI as other income. It was not

until year 3 when the tax preparers realized that the taxpayer was eligible to

exclude cancellation of debt income under the qualified real property business

indebtedness exclusion. The taxpayer subsequently filed a request for an

extension to file a late election. The IRS allowed the taxpayer to file an

amended return in order for the individual to make the election under Treas.

Reg. § 301.9100-3(c)(1).

(3) An eligible taxpayer can make this election to exclude CODI and reduce the

basis of depreciable real property by the amount of discharged qualified real

property business indebtedness. To qualify for this exclusion, IRC §

108(c)(3)(A) requires that the real property must be “used in a trade or

business.” Facts and circumstances must be considered in each case. Rental

real estate may qualify under this exclusion if the rental rises to the level of a

trade or business. However, the following situations may not qualify under this

exclusion.

• Generally, a taxpayer who is bankrupt or who is insolvent is not eligible for

this exclusion, as shown in Table 2, Order and Coordination of Exclusions,

discussed earlier. However, a taxpayer may qualify for more than one

exclusion.

• Generally, farm indebtedness does not qualify for the qualified real

property business indebtedness exclusion, as shown in Table 2, Order

and Coordination of Exclusions, discussed earlier.

• Generally, a rental is not a trade or business. Holding property for the

production of rents does not necessarily constitute a trade or business for

purposes of IRC § 162.

(4) PLR 9426006, 1994 WL 312382 states, “…a rental of even a single property

may constitute a trade or business under various Internal Revenue Code

provisions…However, the ownership and rental of real property does not, as a

matter of law, constitute a trade or business. Curphey v. Commissioner, 73 T.C.

at 766 (1980) The issue is ultimately one of fact in which the scope of a

taxpayer's activities, either personally or through agents, in connection with the

30

property, are so extensive as to rise to the stature of a trade or business.”

Bauer v. Commissioner, 168 F.Supp. 539, 541 (Ct.Cl.1958).

(5) Qualified real property business indebtedness is defined as indebtedness that

meets all of the following requirements:

• The debt was incurred or assumed by the taxpayer in connection with real

property used in a trade or business and is secured by such real property.

• It was incurred or assumed before January 1, 1993, or, if it was incurred or

assumed after such date, it is "qualified acquisition indebtedness”.

• It is indebtedness with respect to which the taxpayer makes an election to

have it treated as qualified real property business indebtedness.

(6) IRC § 108(c)(4) defines qualified acquisition indebtedness as, with respect to

any real property used in a trade or business, indebtedness secured by such

property and incurred or assumed to acquire, construct, reconstruct or

substantially improve such property. Qualified real property business

indebtedness can include land used in a trade or business. Qualified real

property business indebtedness includes refinanced debt, but only to the extent

that the refinanced debt does not exceed the debt being refinanced.

(7) There are two limitations, (1) the debt in excess of value and (2) the overall

limitation on the amount of discharged qualified real property business debt that

can be excluded from gross income under IRC § 108(c)(2) and further

described in Treas. Reg. § 1.108-6.

(8) In applying the first limitation, the amount of qualified real property business

indebtedness excludible from gross income cannot exceed the excess of the

outstanding principal amount of the qualified real property business debt

(immediately before the discharge) over the fair market value (immediately

before the discharge) of the business real property that secures the discharged

debt, less, the outstanding principal amount of any other qualified real property

business debt that secures the property immediately before the discharge.

(9) In applying the second or overall limitation, the excluded debt amount should

not be more than the aggregate adjusted bases of depreciable real property

held immediately before the discharge, (excluding depreciable real property

acquired in contemplation of the discharge) reduced by the sum of depreciation

claimed for the taxable year that CODI was excluded under this exclusion plus,

reductions to the adjusted bases of depreciable real property required under

IRC § 108(b) (e.g., bankruptcy or insolvency exclusions) for the same taxable

year plus, reductions to the adjusted bases of depreciable real property

required under IRC § 108(g), the qualified farm exclusion, for the same taxable

year.

31

D.1. Example

(1) Example 11 (Part I of Example 25, Chapter 4). Peter bought a grocery store

in year 1 that he operated as his sole proprietorship. Peter made a $25,000

down payment and financed the remaining $250,000 of the purchase price with

a bank loan. The bank loan documents indicated that it was a recourse loan,

secured by the property. Peter had no other debt secured by that depreciable

real property. In addition to the grocery store, Peter owned depreciable

equipment and furniture with an adjusted basis of $76,000.

(2) Peter’s business encountered financial difficulties in year 6. In year 7, Peter was

approved for a loan modification with the lender and $25,000 of the outstanding

balance of the debt was canceled.

(3) Other facts, immediately before the cancellation of debt include the following:

• Peter was not bankrupt and he was not insolvent

• Outstanding principal balance on the grocery store loan was $195,000

• FMV of the store was $172,000

• Adjusted basis of the store was $227,161

• The bank sent Peter a Form 1099-C for year 7. There was no information

in boxes 3, 5, 6 or 7, $25,000 was reported in Box 2

(4) Before the qualified real property business is considered, Peter must first

determine whether he qualifies to exclude CODI under the bankruptcy and

insolvency exclusions. In this case, Peter does not qualify for either exclusion

and may proceed with the qualified real property business exclusion.

(5) Peter looks to the limitations under the qualified real property business

indebtedness exclusion for the CODI of $25,000. The debt in excess of value

limitation was $23,000 ($195,000 outstanding loan amount immediately before

the discharge minus $172,000 fair market value of the property). Peter did not

have an outstanding principal amount of any other qualified real property

business debt secured by the property.

(6) The amount of excluded debt cannot exceed the overall limitation of $220,286

($227,161 aggregate adjusted bases of depreciable real property held before

the discharge minus $6,875 depreciation claimed in the year of discharge).

Peter did not have any basis reductions made under IRC § 108(b) or IRC §

108(g) for the same taxable year.

32

(7) Peter’s CODI exclusion of $23,000 for year 7 is limited to the overall limitation of

$220,286. The overall limitation is more than the exclusion limitation amount

therefore; $23,000 can be excluded from Schedule C gross income under the

qualified real property business indebtedness exclusion. Peter would report

$2,000 ($25,000 CODI minus $23,000 Limitation) as other income on his

Schedule C for year 7.