A Financial System

That Creates Economic Opportunities

Nonbank Financials, Fintech,

and Innovation

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

JULY 2018

TREASURY

T

H

E

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

N

T

O

F

T

H

E

T

R

E

A

S

U

R

Y

1

7

8

9

2018-04417 (Rev. 1) • Department of the Treasury • Departmental Ofces • www.treasury.gov

A Financial System

That Creates Economic Opportunities

Nonbank Financials, Fintech,

and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

T

H

E

D

E

P

A

R

T

M

E

N

T

O

F

T

H

E

T

R

E

A

S

U

R

Y

1

7

8

9

Report to President Donald J. Trump

Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles

for Regulating the United States Financial System

Steven T. Mnuchin

Secretary

Craig S. Phillips

Counselor to the Secretary

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

ii

Staff Acknowledgments

Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for

their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Jessica Renier

and W. Moses Kim, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, Dan Dorman, Alexan-

dra Friedman, Eric Froman, Dan Greenland, Gerry Hughes, Alexander Jackson, Danielle

Johnson-Kutch, Ben Lachmann, Natalia Li, Daniel McCarty, John McGrail, Amyn Moolji,

Brian Morgenstern, Daren Small-Moyers, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bimal Patel,

Brian Peretti, Scott Rembrandt, Ed Roback, Ranya Rotolo, Jared Sawyer, Steven Seitz,

Brian Smith, Mark Uyeda, Anne Wallwork, and Christopher Weaver.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

iii

Table of Contents

Executive Summary 1

Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation 4

Emerging Trends in Financial Intermediation 6

Summary of Issues and Recommendations 9

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology 15

Digitization 17

Consumer Financial Data 22

e Potential of Scale 44

Aligning the Regulatory Framework to Promote Innovation 61

Challenges with State and Federal Regulatory Frameworks 63

Modernizing Regulatory Frameworks for National Activities 66

Updating Activity-Specic Regulations 81

Lending and Servicing 83

Payments 144

Wealth Management and Digital Financial Planning 159

Enabling the Policy Environment 165

Agile and Effective Regulation for a 21st Century Economy 167

International Approaches and Considerations 177

Appendices

Appendix A: Participants in the Executive Order Engagement Process 187

Appendix B: Table of Recommendations 195

Appendix C: Additional Background 213

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

iv

Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronym/Abbreviation Term

ABA American Bankers Association

ACH Automated Clearing House

AI Articial Intelligence

AMC Appraisal Management Company

AML Anti-Money Laundering

API Application Programming Interface

APR Annual Percentage Rate

AQB Appraiser Qualications Board

ASB Appraisal Standards Board

ATM Automated Teller Machine

AVM Automated Valuation Model

BHC Bank Holding Company

BHC Act Bank Holding Company Act

BSA Bank Secrecy Act

Bureau Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection

CEG Cybersecurity Expert Group

C.F.R. Code of Federal Regulations

CFT Countering the Financing of Terrorism

CFTC U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission

CHAPS Clearing House Automated Payment System

CHIPS Clearing House Interbank Payments System

CMA Competition and Markets Authority (U.K.)

CRA Community Reinvestment Act

CROA Credit Repair Organizations Act

CSBS Conference of State Bank Supervisors

Cyber Apex Next Generation Cyber Infrastructure Apex Program

DARPA Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

DHS U.S. Department of Homeland Security

DIUx Defense Innovation Unit Experimental

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

v

DLT Distributed Ledger Technology

DOD U.S. Department of Defense

Dodd-Frank Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

DOJ U.S. Department of Justice

DOL U.S. Department of Labor

Education U.S. Department of Education

EMV Europay, Mastercard, and Visa

ESIGN Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act

E.U. European Union

FATF Financial Action Task Force

FBIIC Financial and Banking Information Infrastructure Committee

FCA False Claims Act

FCA U.K. Financial Conduct Authority

FCC Federal Communications Commission

FCRA Fair Credit Reporting Act

FDCPA Fair Debt Collection Practices Act

FDIC Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

FedACH Federal Reserve Banks’ Automated Clearing House

FFIEC Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council

FHA Federal Housing Administration

FHA-HAMP FHA Home Aordable Modication Program

FHFA Federal Housing Finance Agency

FHLB Federal Home Loan Bank

FICO Fair Isaac Corporation

FIL Financial Institutions Letter

FinCEN Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

FINRA Financial Industry Regulatory Authority

Fintech Financial Technology

FIRREA Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act

FlexMod GSE Flex Modication

FPS Faster Payments Service (U.K.)

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

vi

FRB Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

FRBNY Federal Reserve Bank of New York

FSB Financial Stability Board

FS-ISAC Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center

FTC Federal Trade Commission

G-7 Group of 7

G20 Group of 20

GAO U.S. Government Accountability Oce

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GDPR General Data Protection Regulation (E.U.)

GLBA Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

GRC Governance, Risk and Compliance

GSE Government-Sponsored Enterprise

HUD U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

IaaS Infrastructure as a Service

IRS Internal Revenue Service

ISO International Organization for Standardization

IT Information Technology

LOA Levels of Assurance

MAS Monetary Authority of Singapore

MBA Mortgage Bankers Association

MBS Mortgage-Backed Securities

MCSBA Maryland Credit Services Business Act

MERS Mortgage Electronic Registration System

MMIF Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund

MPL Marketplace Lender

MSB Money Services Business

MTRA Money Transmitter Regulators Association

NACHA National Automated Clearinghouse Association

NAIC National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NBA National Bank Act

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

vii

NCUA National Credit Union Administration

NFC Near Field Communication

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NMLS Nationwide Mortgage Licensing System or Nationwide Multistate

Licensing System

NSF National Science Foundation

NSS National Settlement Service

OBIE Open Banking Implementation Entity (U.K.)

OCC Oce of the Comptroller of the Currency

OFX Open Financial Exchange

P2P Person-to-Person or Peer-to-Peer

PaaS Platform as a Service

PCI-DSS Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard

PII Personally Identiable Information

PIN Personal Identication Number

PLS Private-Label Securities

PSD2 Revised Payment Services Directive (E.U.)

PSP Payment Service Provider

RTP Real Time Payments

SaaS Software as a Service

SAFE Act Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act

SEC U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

SIFMA Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association

SRO Self-Regulatory Organization

SWIFT Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication

SWIFT GPI Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication Global

Payments Innovation

TCH e Clearing House

TCPA Telephone Consumer Protection Act

TFFT Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s Task Force on Financial

Technology

Treasury U.S. Department of the Treasury

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

viii

U.K. United Kingdom

U.S. United States

UDAAP Unfair, Deceptive, or Abusive Acts or Practices

UDAP Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices

UETA Uniform Electronic Transactions Act

URPERA Uniform Real Property Electronic Recording Act

U.S.C. United States Code

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

USPAP Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice

VA U.S. Department of Veterans Aairs

ZB Zettabyte

Executive Summary

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Introduction

3

Introduction

President Donald J. Trump established the policy of his Administration to regulate the U.S. nan-

cial system in a manner consistent with a set of Core Principles. ese principles were set forth in

Executive Order 13772 on February 3, 2017. e U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury),

under the direction of Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin, prepared this report in response to that

Executive Order. e reports issued pursuant to the Executive Order identify laws, treaties, regula-

tions, guidance, reporting, and record keeping requirements, and other Government policies that

promote or inhibit federal regulation of the U.S. nancial system in a manner consistent with the

Core Principles.

e Core Principles are:

A. Empower Americans to make independent nancial decisions and informed choices in the

marketplace, save for retirement, and build individual wealth;

B. Prevent taxpayer-funded bailouts;

C. Foster economic growth and vibrant nancial markets through more rigorous regulatory

impact analysis that addresses systemic risk and market failures, such as moral hazard and

information asymmetry;

D. Enable American companies to be competitive with foreign rms in domestic and foreign

markets;

E. Advance American interests in international nancial regulatory negotiations and meetings;

F. Make regulation ecient, eective, and appropriately tailored; and

G. Restore public accountability within federal nancial regulatory agencies and rationalize the

federal nancial regulatory framework.

Scope of This Report

e nancial system encompasses a wide variety of institutions and services, and accordingly,

Treasury has delivered a series of four reports related to the Executive Order covering:

• e depository system, covering banks, savings associations, and credit unions of all sizes,

types, and regulatory charters (the Banking Report,

1

which was publicly released on June

12, 2017);

• Capital markets: debt, equity, commodities and derivatives markets, central clearing, and

other operational functions (the Capital Markets Report,

2

which was publicly released on

October 6, 2017);

1. U.S. Department of the Treasury, A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Banks and Credit

Unions (June 2017).

2. U.S. Department of the Treasury, A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Capital Markets

(Oct. 2017).

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Review of the Process for This Report

4

• e asset management and insurance industries, and retail and institutional investment

products and vehicles (the Asset Management and Insurance Report,

3

which was publicly

released on October 26, 2017); and

• Nonbank nancial institutions, nancial technology, and nancial innovation (this report).

Review of the Process for This Report

For this report, Treasury incorporated insights from the engagement process for the previous three

reports issued under the Executive Order and also engaged with additional stakeholders focused on

data aggregation, nonbank credit lending and servicing, payments networks, nancial technology,

and innovation. Over the course of this outreach, Treasury consulted extensively with a wide range

of stakeholders, including trade groups, nancial services rms, federal and state regulators, con-

sumer and other advocacy groups, academics, experts, investors, investment strategists, and others

with relevant knowledge. Treasury also reviewed a wide range of data, research, and published

material from both public and private sector sources.

Treasury incorporated the widest possible range of perspectives in evaluating approaches to regula-

tion of the U.S. nancial system according to the Core Principles. A list of organizations and

individuals who provided input to Treasury in connection with the preparation of this report is set

forth as Appendix A.

Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Nonbank nancial rms play important roles in providing nancial services to U.S. consumers

and businesses by providing credit to the economy across a wide range of retail and commercial

asset classes. Nonbanks are well integrated into the U.S. payments system and play key roles such

as facilitating back-end check processing; enabling card issuance, processing, and network activi-

ties; and providing customer-facing digital payments software. Nonbank nancial rms also play

important roles in capital markets and in providing nancial advice and execution services to retail

investors, among a range of other services.

e nancial crisis altered the environment in which banks and nonbanks compete to pro-

vide nancial services. Specically, many traditional nancial companies such as banks, credit

unions, and insurance companies experienced signicant distress during the crisis. is distress

caused the insolvency or restructuring of many existing nancial companies, particularly those

with volatile funding sources and concentrated balance sheets. e government responded to

this distress, and the unprecedented magnitude of taxpayer support it triggered, by writing far-

reaching laws that mandated the adoption of hundreds of new regulations. In some cases, these

policy changes made certain product segments unprotable for banks, thereby driving activity

3. U.S. Department of the Treasury, A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities: Asset

Management and Insurance (Oct. 2017).

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

5

outside of the banking sector and creating opportunities for emerging nonbank nancial rms

to address unmet market demands.

At the same time, and as part of a longer-term trend, the rapid development of nancial technolo-

gies has enabled nancial services rms to improve operational eciencies and lower regulatory

compliance costs that increased as a result of the expansion of regulations following the nancial

crisis. Since the nancial crisis, there has been a proliferation in technological capabilities and

processes at increasing levels of cost eectiveness and speed. e use of data, the speed of commu-

nication, the proliferation of mobile devices and applications, and the expansion of information

ow all have broken down barriers to entry for a wide range of startups and other technology-based

rms that are now competing or partnering with traditional providers in nearly every aspect of the

nancial services industry.

e landscape for nancial services has changed substantially. From 2010 to the third quarter of

2017, more than 3,330 new technology-based rms serving the nancial services industry have

been founded, 40% of which are focused on banking and capital markets.

4

In the aggregate, the

nancing of such rms has been growing rapidly, reaching $22 billion globally in 2017, a thirteen-

fold increase since 2010.

5

Signicantly, lending by such rms now makes up more than 36% of all

U.S. personal loans, up from less than 1% in 2010.

6

Additionally, some digital nancial services

reach up to some 80 million members,

7

while consumer data aggregators can serve more than 21

million customers.

8

Important trends have arisen as a consequence of these factors, including:

• e nonbank sector has responded opportunistically to the pullback in services and

increased regulatory challenges placed on traditional nancial institutions, including the

launch of numerous startup platforms;

• Many of these platforms have rapidly grown beyond the startup phase, employing

technology-enabled approaches to customer acquisition and process support for

their services;

• Innovative new platforms in the nonbank nancial sector are, in some cases, standalone

providers, while others have focused on providing support for or interconnectivity with

traditional nancial institutions through partnerships, joint ventures, or other means;

4. Deloitte, Fintech by the Numbers: Incumbents, Startups, Investors Adapt to Maturing Ecosystem (2017), at 3

and 7, available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/financial-services/us-dcfs-

fintech-by-the-numbers-web.pdf.

5. Id.

6. Hannah Levitt, Personal Loans Surge to a Record High, Bloomberg (July 3, 2018), available at: https://www.

bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-03/personal-loans-surge-to-a-record-as-fintech-firms-lead-the-way

(analyzing data from TransUnion).

7. Credit Karma, Press Release – Credit Karma and Silver Lake Announce $500 Million Strategic Secondary

Investment (Mar. 28, 2018), available at: https://www.creditkarma.com/pressreleases.

8. Envestnet, 2017 Annual Report, at 8, available at: http://www.envestnet.com/report/2017/download/EN-2017-

AnnualReport-Final.pdf.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Emerging Trends in Financial Intermediation

6

• Large technology companies with access to vast stores of consumer data have simultane-

ously entered the nancial services industry, primarily in payments and credit provision;

and

• e increasing scale of technology-enabled competitors and the corresponding threat of

disruption has raised the stakes for existing rms to innovate more rapidly and pursue

dynamic and adaptive strategies. As a result, mature rms have launched platforms aimed

at reclaiming market share through alternative delivery systems and at lower costs than

they were previously able to provide.

Consumers increasingly prefer fast, convenient, and ecient delivery of services. New technologies

allow rms with limited scale to access computing power on levels comparable to much larger

organizations. e relative ubiquity of online access in the United States, combined with these new

technologies, allows newer rms to more easily expand their business operations.

In this report, we explore the characteristics of, and regulatory landscape for, nonbank nancial

rms with traditional “brick and mortar” footprints not covered in the previous Core Principles

reports, as well as newer business models employed by technology-based rms. We also address

the ability of banks to innovate internally, as well as partner with such technology-based rms.

Foundational to the report’s ndings, we explore the implications of digitization and its impact on

access to clients and their data, focusing on several thematic areas, including:

• e collection, storage, and use of nancial data;

• Cloud services and “big data” analytics;

• Articial intelligence and machine learning; and

• Digital legal identity and data security.

is report includes a limited treatment of blockchain and distributed ledger technologies. ese

technologies, as well as digital assets, are being explored separately in an interagency eort led by

a working group of the Financial Stability Oversight Council. e working group is a convening

mechanism to promote coordination among regulators as these technologies evolve.

Emerging Trends in Financial Intermediation

Financial services are being signicantly reshaped by several important trends, including (1) rapid

advances in technology; (2) increased eciencies from the rapid digitization of the economy; and

(3) the abundance of capital available to propel innovation.

Technological Advances in Financial Services

In addition to other benets, innovations in nancial technology expand access to services for

underserved individuals or small businesses and improve the ease of use, speed, and cost of such

services. Businesses providing nancial services benet from opportunities to improve their prod-

uct oerings to win market share and reduce per-customer operational costs.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Emerging Trends in Financial Intermediation

7

Expanded access to credit and nancial services. Digital advice platforms are making nancial plan-

ning tools and wealth management capabilities previously limited to higher net worth households

available to a much broader segment of households. New platforms for lending are developing

business models that take advantage of new types of data and credit analysis, potentially serving

consumer and small business borrower segments that may not otherwise have access to credit

through traditional underwriting approaches. Unbanked or underbanked populations can gain

improved access to banking services through new mobile device-based banking applications.

Expanded speed, convenience, and security. Consumer and business demand for increased

convenience and speed have driven the digitization of nancial services. For example, increased

digitization of the mortgage process has improved the online experience of nancing a home,

but additional innovations could dramatically help to further shorten the time it takes to close

a mortgage, which still took an average of 52 days in 2016.

9

Borrowers seeking to renance or

consolidate higher-rate student loans or other consumer debts can obtain accelerated credit deci-

sions from some lenders, as can small business entrepreneurs looking to expand their business or

manage their seasonality.

Payment systems also benet from innovations that are delivering greater speed and security. e

proliferation of mobile and person-to-person payments allows end-users a way to quickly transfer

money using identiers such as an e-mail address or phone number. Contactless payment methods

that store and tokenize payment information are also increasingly being used and could provide

a more convenient and secure way to pay. ese innovations are helping small businesses to lower

the barriers to receive payments.

Reduced cost of services and operational eciencies. Online marketplace lenders generally oer

unsecured consumer loans that are designed to renance existing higher-rate debts into lower-

rate debt, reducing borrowing costs for consumers. Digital nancial advice providers are able to

leverage technology to scale their services to larger numbers of investors and to provide such services

at more aordable prices than traditional providers. e increasing digitization of payments is

expected to reduce signicant costs in the current payment processes for businesses and rms by,

for example, replacing physical paper checks with electronic payments and reducing ineciencies

in cross-border payments.

Digitization of Finance and the Economy

Changes in the hardware industry, as reected in advances in core computing and data storage

capacity, represent a sea change in capabilities and expand the potential for nancial services to be

provided on a more cost-eective basis. When considered alongside the ubiquity of mobile devices

and the growth in the volume and facility of applications and exibility of mobile communication,

the implications for nancial services are signicant. e collection and storage of data and the

application of advanced computational techniques allow for a new generation of approaches in the

9. Andreas Fuster et al., The Role of Technology in Mortgage Lending, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff

Report No. 836 (Feb. 2018), at 12, available at: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/

staff_reports/sr836.pdf.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Emerging Trends in Financial Intermediation

8

design, marketing, and delivery of nancial services. At the same time, these new approaches may

raise new concerns about data privacy and theft or misuse.

Consider the recent proliferation of digital data available for analysis. By 2020, digitized data is

forecasted to be generated at a level that is more than 40 times the level produced in 2009.

10

In

2012, it was estimated that 90% of the digitized data in the world had been generated in just

the prior two years.

11

Since 2012, more than one billion more people have gained access to the

internet, with 2.5 billion people connected to the internet in 2012 and 3.7 billion people in

2017.

12

Globally, there are an estimated 27 billion devices connected to the internet, including

smartphones, tablets, and computers, with expectations for 125 billion connected devices by the

year 2030.

13

Parallel to these growing improvements in data and connectivity are expanding complementary

technologies, such as cloud computing and machine learning. ese technologies enable rms

to store vast amounts of data and eciently increase computing resources. Unsurprisingly, for

nancial services rms, data analytics and machine learning (or articial intelligence) are two

of the top three areas of tech investment.

14

Other technology developments that are poised to

impact innovation in nancial services include advances in cryptography and distributed ledger

technologies, giving rise to blockchain-based networks.

Investment Capital

e ow of capital into investments in nancial technology is very large. U.S. rms accounted for

nearly half of the $117 billion in cumulative global investments from 2010 to 2017.

15

Unfolding

alongside these investments, many large, well-established rms involved in data, software, cloud

computing, internet search, mobile devices, retail e-commerce, payments, and telecommunications

have begun to engage in activities directly or indirectly related to nancial services. Many of

these rms are based in the United States, including rms having some of the largest market

capitalizations in the world.

e availability of capital, the large size of the nancial services market, and continued advance-

ments in technology make accelerating innovation nearly inevitable. is includes investments

in innovation by traditional nancial institutions, such as banks, asset managers and insurers, to

10. A.T. Kearney, Big Data and the Creative Destruction of Today’s Business Models (2013), at 2, available at:

https://www.atkearney.com/documents/10192/698536/Big+Data+and+the+Creative+Destruction+of+Today

s+Business+Models.pdf/f05aed38-6c26-431d-8500-d75a2c384919 (discussing Oracle forecast).

11. Id.

12. Id.

13. IHS Markit, The Internet of Things: A Movement, Not a Market (Oct. 2017), at 2, available at: https://cdn.ihs.

com/www/pdf/IoT_ebook.pdf. For projections that do not consider computers and phones, see Gartner, Inc.,

Press Release – Gartner Says 8.4 Billion Connected “Things” Will be in Use in 2017, up 31 Percent from

2016 (Feb. 7, 2017), available at: https://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3598917.

14.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, Redrawing the Lines: FinTech’s Growing Influence on Financial Services (2017), at

9, available at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/financial-services/assets/

pwc-global-fintech-report-2017.pdf.

15. Treasury analysis of FT Partners data.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Summary of Issues and Recommendations

9

provide higher quality, more secure, and more ecient services while meeting consumer demand

for speed and convenience.

Summary of Issues and Recommendations

Treasury’s review of the regulatory framework for nonbank nancial institutions and innovation

more broadly has identied signicant opportunities to accelerate innovation in the United States

consistent with the Core Principles. is review has identied a wide range of measures that could

promote economic growth, while maintaining strong consumer and investor protections and safe-

guarding the nancial system.

Treasury believes that innovation is critical to the success of the U.S. economy, particularly in the

nancial sector. roughout Treasury’s ndings, opportunities have been identied to modernize

regulation to embrace the use of data, encourage the adoption of advanced data processing and

other techniques to improve business processes, and support the launch of alternative product and

service delivery systems. Support of innovation is critical across the regulatory system — both at

the federal and state levels. Treasury supports encouraging the launch of new business models as

well as enabling traditional nancial institutions, such as banks, asset managers, and insurance

companies, to pursue innovative technologies to lower costs, improve customer outcomes, and

improve access to credit and other services.

Treasury’s recommendations in this report can be summarized in the following four categories:

• Adapting regulatory approaches to changes in the aggregation, sharing, and use of con-

sumer nancial data, and to support the development of key competitive technologies;

• Aligning the regulatory framework to combat unnecessary regulatory fragmentation, and

account for new business models enabled by nancial technologies;

• Updating activity-specic regulations across a range of products and services oered by

nonbank nancial institutions, many of which have become outdated in light of techno-

logical advances; and

• Advocating an approach to regulation that enables responsible experimentation in the

nancial sector, improves regulatory agility, and advances American interests abroad.

A list of all of Treasury’s recommendations in this report is set forth as Appendix B, including the

recommended action, method of implementation (Congressional and/or regulatory action), and

which Core Principles are addressed.

Key themes of Treasury’s recommendations are as follows.

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Competitive Technologies

is report catalogues key elements in the evolution of digitization, data, and scalable technologies

and highlights areas of relevance to many aspects of nancial services, including lending, nancial

advice, and payments. Treasury recommends that key provisions of the Telephone Consumer

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Summary of Issues and Recommendations

10

Protection Act be updated, and believes closing the digital divide to enable the entire U.S. popula-

tion to benet from modern information and communication ow is a priority.

Treasury makes numerous recommendations that would improve consumers’ access to data and

its use by third parties that would support better delivery of services in a responsible manner.

Treasury has identied the need to remove legal and regulatory uncertainties currently holding

back nancial services companies and data aggregators from establishing data-sharing agreements

that would eectively move rms away from screen-scraping to more secure and ecient methods

of data access. e U.S. market would be well served by a solution developed in concert with

the private sector that addresses data sharing, standardization, security, and liability issues. It is

important to explore eorts to mitigate implementation costs for community banks and smaller

nancial services companies with more limited resources to invest in technology. Additionally,

Treasury recommends that Congress enact a federal data security and breach notication law to

protect consumer nancial data and ensure that consumers are notied of breaches in a timely and

consistent manner.

Removing regulatory barriers to foundational technologies, including the development of digital

legal identity, is important to improving nancial inclusion and enabling the use of scalable,

competitive technologies. Similarly, facilitating the further development and incorporation

of cloud technologies, machine learning, and articial intelligence into nancial services is

important to realizing the potential these technologies can provide for nancial services and the

broader economy.

Aligning the Regulatory Framework to Promote Innovation

Many statutes and regulations addressing the nancial sector date back decades. As a result, the

nancial regulatory framework is not always optimally suited to address new business models and

products that continue to evolve in nancial services. is has the potential negative consequence

of limiting innovation that might benet consumers and small businesses. Financial regulation

should be modernized to more appropriately address the evolving characteristics of nancial ser-

vices of today and in the future.

It is important that state regulators strive to achieve greater harmonization, including considering

drafting of model laws that could be uniformly adopted for nancial services companies cur-

rently challenged by varying licensing requirements of each state. Treasury encourages eorts to

streamline and coordinate examinations and to encourage, where possible, regulators to conduct

joint examinations of individual rms. Treasury supports Vision 2020, an eort by the Conference

of State Bank Supervisors that includes establishing a Fintech Industry Advisory Panel to help

improve state regulation, harmonizing multi-state supervisory processes, and redesigning the suc-

cessful Nationwide Multistate Licensing System.

At the federal level, Treasury encourages the Oce of the Comptroller of the Currency to further

develop its special purpose national bank charter, previously announced in December 2016. A

forward-looking approach to federal charters could be eective in reducing regulatory fragmenta-

tion and growing markets by supporting benecial business models.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Summary of Issues and Recommendations

11

Finally, Treasury encourages banking regulators to better tailor and clarify guidance regarding

bank partnerships with nonbank nancial rms, particularly smaller, less-mature companies with

innovative technologies that do not present a material risk to the bank. Treasury believes it is

important to encourage the partnership model to promote innovation. Further, Treasury makes

recommendations regarding changes to permissible activities, including bank activities related to

acquiring or investing in nonbank platforms.

Updating Activity-Specific Regulations

is report surveys a wide range of activities where specic recommendations for regulatory reform

are suggested. e range of nancial services includes:

Marketplace Lending

Marketplace lenders are expanding access to credit for consumers and businesses in the United

States. Treasury recognizes that partnerships between banks and marketplace lenders have been

valuable to enhance the capabilities of mature nancial rms. Treasury recommends eliminating

constraints brought about by recent court cases that would unnecessarily limit the functioning

of U.S. credit markets. Congress should codify the “valid when made” doctrine and the role of

the bank as the “true lender” of loans it makes. Federal banking regulators should also use their

available authorities to address both of these challenges.

Mortgage Lending and Servicing

Treasury recognizes that the primary residential mortgage market has experienced a fundamental

shift in composition since the nancial crisis, as traditional deposit-based lender-servicers have

ceded sizable market share to nonbank nancial rms, with the latter now accounting for approxi-

mately half of new originations. Some of this shift has been driven by the post-crisis regulatory

environment, including enforcement actions brought under the False Claims Act for violations

related to government loan insurance programs. Additionally, many nonbank lenders have ben-

etted from early adoption of nancial technology innovations that speed up and simplify loan

application and approval at the front-end of the mortgage origination process. Policymakers should

address regulatory challenges that discourage broad primary market participation and inhibit the

adoption of technological developments with the potential to improve the customer experience,

shorten origination timelines, facilitate ecient loss mitigation, and generally deliver a more reli-

able, lower cost mortgage product.

Student Lending and Servicing

e federal student loan program represents more than 90% of outstanding student loan volume

and is managed by an extensive network of nonbanks for servicing and debt collection. e pro-

gram is complex due to a variety of loan types, repayment plans, and product features that make

the program dicult for borrowers to navigate and increase the diculty and cost of servicing.

Treasury recommends that the U.S. Department of Education establish and publish minimum

eective servicing standards to provide servicers clear guidelines for servicing and help set expecta-

tions about how the servicing of federal loans is regulated. Treasury provides recommendations

related to the greater use of technology in communications with borrowers, enhanced portfolio

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Summary of Issues and Recommendations

12

performance monitoring and management by Education, and greater institutional accountability

for schools participating in the federal nancial aid programs.

Short-Term, Small-Dollar Lending

While the demand for short-term, small-dollar loans is high, lenders have been constrained by

unnecessary regulatory guidance at the federal level. Treasury recommends that the Bureau of

Consumer Financial Protection (Bureau) rescind its Payday Rule, which applies to nonbank short-

term, small-dollar lenders, as the states already maintain the necessary regulatory authorities and

the rule would further restrict consumer access to credit. Treasury also recommends that both

federal and state banking regulators take steps to encourage prudent and sustainable short-term,

small-dollar installment lending by banks.

Debt Collection

Debt collectors and debt buyers play an important role in minimizing losses in consumer credit

markets, thereby allowing for increased availability of and lower priced credit to consumers. A

variety of stakeholders have expressed concerns about the adequacy of loan information provided

when a loan is sold or transferred for collection. When debt collectors and buyers do not receive

adequate information, they are unable to demonstrate to the consumer that the debt is valid and

owed. Treasury recommends the Bureau establish minimum eective federal standards for third-

party debt collectors, including standards for the information that must be transferred with the

debt for purposes of third-party collection or sale.

New Credit Models and Data

A growing number of rms have begun to use or explore a wide range of newer data sets or

advanced algorithms, including machine learning-based methods, to support credit underwriting

decisions. Treasury recognizes that these new credit models and data sources have the potential to

meaningfully expand access to credit and the quality of nancial services, and therefore recom-

mends that nancial regulators further enable their testing. In particular, regulators should provide

regulatory clarity for the use of new data and modeling approaches that are generally recognized as

providing predictive value consistent with applicable law for use in credit decisions.

Credit Bureaus

e consumer credit bureaus collect sensitive information on millions of Americans, and thus are

required to protect the information they collect. While the credit bureaus are subject to state and

federal regulation for consumer protection purposes, and have been subject to state and federal

enforcement actions related to data security, they are not routinely supervised for compliance with

the federal data security requirements of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act. Treasury recommends that

the relevant agencies use appropriate authorities to coordinate regulatory actions to protect con-

sumer data held by credit reporting agencies and that Congress continue to assess whether further

authority is needed in this area. Treasury also recommends that Congress amend the Credit Repair

Organizations Act to exclude national credit bureaus and national credit scorers in order to allow

these entities to provide credit education and counseling services to consumers to prospectively

improve their credit scores.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Summary of Issues and Recommendations

13

IRS Income Verication

e Internal Revenue Service (IRS) system that lenders and vendors use to obtain borrower tax

transcripts is outdated and should be modernized in order to minimize delays in accessing tax

information, which would facilitate the consumer and small business credit origination process.

In other data aggregation situations, such as gathering borrower bank balances, lenders generally

are able to obtain the needed borrower nancial information through an application program-

ming interface (API) to instantaneously and safely transfer data. e IRS’s current technology

should be updated to accommodate lender access of borrower information to instantaneously

and safely transfer data, comparable to similar private sector solutions. While the IRS is working

to update its technology more broadly, these eorts would benet from additional funding,

which would facilitate upgrades to support more ecient income verication, bringing a critical

component of the credit process up to speed with broader innovations in nancial technology.

Payments

Treasury recommends that the states work to harmonize money transmitter requirements for

licensing and supervisory examinations, and urges the Bureau to provide more exibility regarding

the issuance of remittance disclosures. Treasury encourages the Federal Reserve to move quickly

in facilitating a faster retail payments system, such as through the development of a real-time

settlement service that would allow for more ecient and widespread access to innovative payment

capabilities. Such a system should take into account the ability of smaller nancial institutions, such

as community banks and credit unions, to access innovative technologies and payment services.

Wealth Management and Digital Financial Planning

Digital nancial planning tools can expand access to advice for Americans to accumulate suf-

cient wealth, particularly as individuals have become more responsible for their own retirement

planning. Under the current regulatory structure, nancial planners may be regulated at both

the federal and state levels. Although many nancial planners are regulated by the Securities and

Exchange Commission or state securities regulators, they may also be subject to regulation by the

Department of Labor, the Bureau, federal or state banking regulators, state insurance commission-

ers, state boards of accountancy, and state bars. is patchwork of regulatory authority increases

costs and potentially presents unnecessary barriers to the development of digital nancial planning

services. Treasury recommends that an appropriate existing regulator of a nancial planner be

tasked with primary oversight of that nancial planner and other regulators defer to that regulator.

Regulating a 21st Century Economy

Treasury advocates an agile approach to regulation that can evolve with innovation. It is critical

not to allow fragmentation in the nancial regulatory system, at both the federal and state level,

to interfere with innovation. Financial regulators must consider new approaches to eectively

promote innovation, including permitting meaningful experimentation by nancial services rms

to create innovative products, services, and processes.

Internationally, many countries have established “innovation facilitators” and various regulatory

“sandboxes” — testing grounds for innovation. ese sandboxes have each generally supported

common principles, such as promoting the adoption and growth of innovation in nancial services,

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Executive Summary • Summary of Issues and Recommendations

14

providing access to companies in various stages of the business lifecycle, providing varying degrees

of regulatory relief while maintaining consumer protections, and improving the timeliness of regu-

lator feedback oered throughout the development lifecycle. While replicating this approach in

the United States is complicated by the fragmentation of our nancial regulatory system, Treasury

is committed to working with federal and state nancial regulators to establish a unied solution

that accomplishes these objectives — in essence, a regulatory sandbox.

e ability of regulators to engage with the private sector to test and understand new technolo-

gies and innovations as they arise is equally important. Treasury recommends that Congress pass

legislation authorizing nancial regulators to use other transaction authority for research and

development and proof of concept technology projects. Treasury encourages nancial regulators to

pursue robust engagement eorts with industry and establish clear points of contact for outreach

to enable the symbiotic relationship necessary to maintaining U.S. global competitiveness.

Treasury will work to ensure actions taken by international organizations align with U.S. national

interests and the domestic priorities of U.S. regulatory authorities. is should include a focus on

the needs of U.S. companies that operate on a global basis. Participation by the relevant experts

in international forums and standard-setting bodies is important to share experiences regarding

respective regulatory approaches and to benet from lessons learned.

A Bright Future for Innovation

e United States is the global leader in technological innovation. e pace of technological devel-

opment in nancial services has increased exponentially, oering potential benets to the U.S.

economy. Treasury encourages all nancial regulators to stay abreast of developments in technology

and to properly tailor regulations in a manner that does not constrain innovation. Regulators must

be more agile than in the past in order to fulll their statutory responsibilities without creating

unnecessary barriers to innovation. Ensuring a bright future for nancial innovation, regulators

should take meaningful steps to facilitate and enhance the nation’s strength in technology and

work toward the common goals of fostering vibrant nancial markets and promoting growth

through responsible innovation.

Embracing Digitization,

Data, and Technology

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Overview

17

Overview

e cost of collecting, transmitting, and storing vast amounts of data has sharply declined over the

last 20 years, which has driven a technological revolution in many industries. Related technologies

built on top of this increased ability to collect and manage data, like machine learning and articial

intelligence, have enabled a wide range of practical applications, many of which are relevant to the

nancial services industry. e combination of digitization, data, and technology can promote

economic growth, increase consumer satisfaction, and improve choice, opportunity, and economic

inclusion for all Americans. ese factors also stimulate innovation, increase competition, and

enhance the global competitiveness of the United States.

Key upgrades to the regulatory system are needed to enable the nancial system to realize the ben-

ets of economy-wide advances in these new technologies, including updating rules for nancial

services in the digital economy, assuring the existence of secure and open access to nancial data,

and aligning requirements for core infrastructure and competitive technologies. In each instance,

there is a signicant role for both the public and private sector — in fact, collaboration between

the two is essential. Likewise, many regulations were adopted in and for a very dierent era, requir-

ing a focus on modernization and appropriate tailoring that is consistent with the Core Principles.

Digitization

e transformation of business into the digital era has had a profound impact on innovation

and economic growth. Converting information into digital form made it possible for data to

be electronically stored, transmitted, and analyzed. As the costs of storing and processing data

have decreased, the amounts of data collected and retained have correspondingly increased. When

combined with developments in communication and networking, the modern economy exists in

a digital environment that allows near-instantaneous access to signicant volumes of information.

Ensuring this data is used in a manner that safely creates new products and services with positive

eects on the economy and society is an important national objective.

e key driver of this digital business environment is the increasingly widespread use of digital

devices by Americans. Consider that nearly 90% of U.S. adults are online.

16

Moreover, 77% own a

mobile phone with advanced digital capabilities, 53% own a tablet, and 46% have used digital voice

assistants.

17

Most Americans use a combination of phone calls, text messages, and e-mails to manage

their business and personal relationships. As a result, Americans’ digital addresses (e.g., e-mail, device,

chat ID) have increasingly become the equivalent of what a physical mailing address or telephone

landline was in the past — the most eective way to reach a person for a business purpose.

16. Pew Research Center, Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet (Feb. 5, 2018), available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/

fact-sheet/internet-broadband/.

17.

Kenneth Olmstead, Pew Research Center, Nearly Half of Americans Use Digital Voice Assistants, Mostly on

their Smartphones (Dec. 12, 2017), available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/12/12/nearly-

half-of-americans-use-digital-voice-assistants-mostly-on-their-smartphones/; Pew Research Center, Mobile

Fact Sheet (Feb. 5, 2018), available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Digitization

18

0

20

40

60

80

100

Social Media

Tablet

Broadband*

Internet

Smartphone

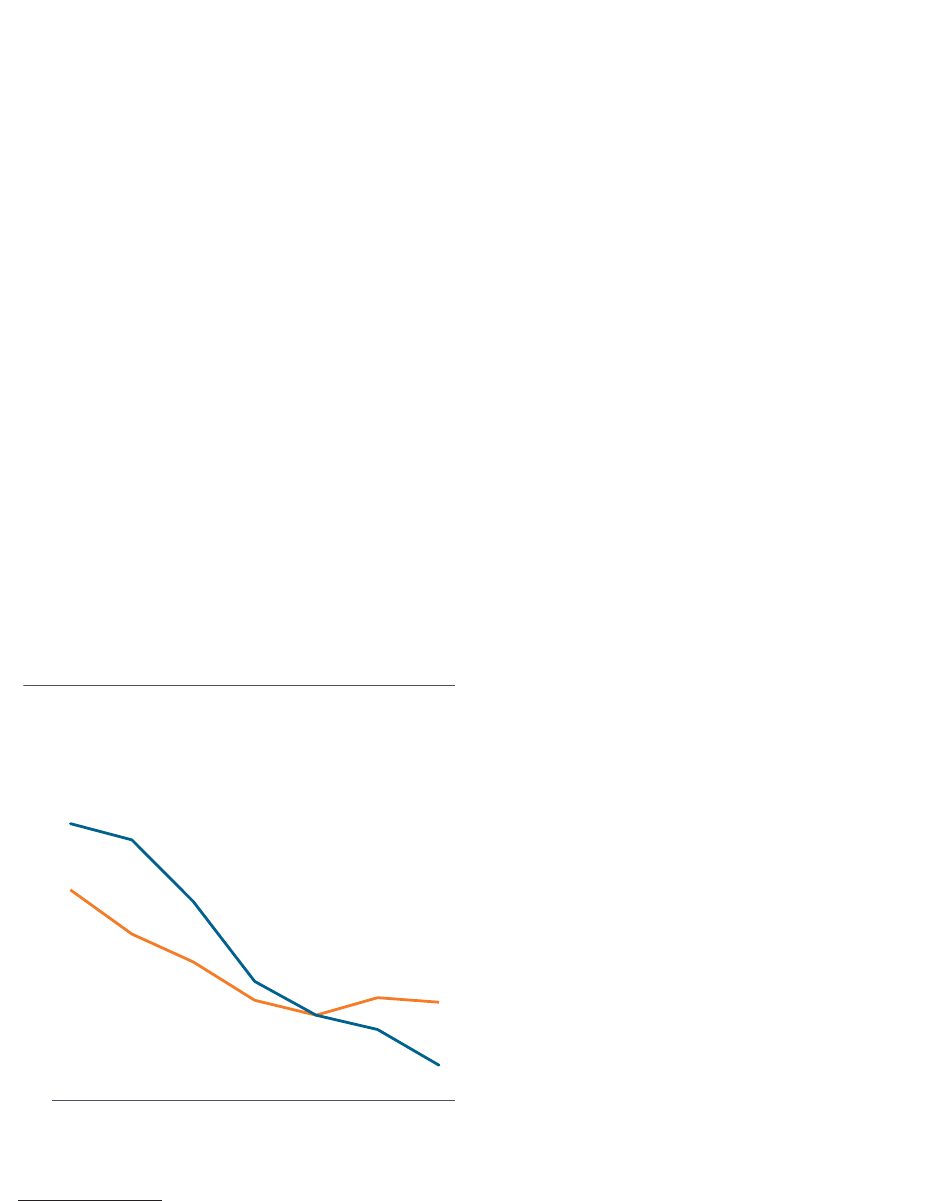

Figure 1: Technology Adoption and Usage

51%

38%

Mobile

banking**

33%

17%

2015

2017

Fintech

services***

Percent of U.S. adults who own

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

* used at home.

** as a percentage of survey respondents that have a bank account.

*** as a percentage of survey respondents that are active online.

Source (left): Chart and data recreated from Pew Research Center analysis.

Sources (right): For mobile banking data, Federal Reserve analysis of Survey of Household Economics and

Decisionmaking and Survey of Consumers’ Use of Mobile Financial Services.

For fintech services growth, see Ernst and Young, EY FinTech Adoption Index 2017, at 13.

Financial institutions and technology-focused rms have recognized this shift in where consum-

ers “reside” and have consequently been transforming their business activities to meet customers’

demand for digital interaction where possible. Consumers are rapidly adopting services provided

by new ntech companies. Survey data indicate that up to one-third of online U.S. consumers

use at least two ntech services — including nancial planning, savings and investment, online

borrowing, or some form of money transfer and payment.

18

Banking is also increasingly digital. Today, 50% of people with bank accounts use mobile devices

to access their information, up from 20% in 2011,

19

while the number of physical bank branches

18. Ernst & Young Global Limited, EY FinTech Adoption Index 2017: The Rapid Emergency of FinTech (2017),

available at: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-fintech-adoption-index-2017/%24FILE/ey-fin-

tech-adoption-index-2017.pdf.

19.

Ellen A. Merry, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Mobile Banking: A Closer Look at Survey

Measures, FEDS Notes (Mar. 27, 2018), available at: https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2163.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Digitization

19

has been declining since 2009.

20

U.S. banks of all sizes are enabling digital engagement with their

customers and are increasingly oering mobile phone applications that provide for a full suite of

banking services, among other eorts.

is digital transformation of the economy and nancial services requires wide-ranging changes

to the U.S. regulatory system. For example, there is a need to modernize regulations for digitally

communicating with consumers. Other regulations that should be implemented are discussed

throughout this report and include: updating regulations to better facilitate secure access to digi-

tized data, authentication of digital identity, and support for core nancial service activities such as

lending, payments, and investment advice.

Digital Communications

Telephone Consumer Protection Act

In 1991, Congress passed the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA) to restrict telemarket-

ing calls and the use of automatic telephone dialing systems (autodialers) and prerecorded voice

messages.

21

e Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is responsible for rules implement-

ing the TCPA. Among the restrictions, the TCPA forbids telemarketers from calling a cell phone

using an autodialer without rst obtaining prior express consent of the called party.

22

However,

current implementation of the TCPA constrains the ability of nancial services rms to use digital

communication channels to communicate with their customers despite consumers’ increasing reli-

ance on text messaging and e-mail communications through their mobile devices.

In 2015, the FCC issued an order responding to 21 requests for clarication or amendment to

the FCC’s TCPA rules and orders.

23

Financial services rms raised three primary concerns with

the FCC’s 2015 order. First, the denition of autodialer was overly broad because it included the

capacity to make an autodialed call, as opposed to the actual use of the equipment as an autodialer.

Second, by only providing a one-call safe harbor, which permitted a caller only a single call to

determine whether a phone number was reassigned, the FCC order exposed rms to signicant

liability — up to a $500-per-call penalty — for dialing reassigned numbers, even when one call

was insucient to permit the rm to learn that the number was reassigned. ird, the order per-

mitted consumers to revoke consent “using any reasonable method,” and prohibited callers from

“infring[ing] on that ability by designating an exclusive means to revoke.”

24

Regarding revocation,

rms asked for clear guidance detailing reasonable methods of revocation given the TCPA’s penal-

ties for noncompliance.

20. Julie Stackhouse, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Why Are Banks Shuttering Branches?, On the

Economy Blog (Feb. 26, 2018), available at: https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2018/february/

why-banks-shuttering-branches.

21. Public Law No. 102-243 [codified at 47 U.S.C. § 227].

22. 47 U.S.C. § 227(b)(1)(A).

23. See Federal Communications Commission, In the Matter Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone

Consumer Protection Act of 1991 et al., Declaratory Rule and Order, CG Docket No. 02-278 (June 18, 2015),

available at: https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-15-72A1_Rcd.pdf (“FCC 2015 Order”).

24.

Id. at 7996.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Digitization

20

On March 16, 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled on these three issues in

a case brought against the FCC by ACA International, a trade group representing debt collectors.

25

First, the D.C. Circuit held that the FCC’s denition of autodialer was arbitrary and capricious

because, under the FCC’s denition, “all smartphones qualify as autodialers because they have

the inherent ‘capacity’ to gain [autodialer] functionality by downloading an app.”

26

Second, the

Court held that the one-call safe harbor was arbitrary and capricious because the FCC failed to

explain why a “caller’s reasonable reliance on a previous subscriber’s consent necessarily cease[s] to

be reasonable once there has been a single, post-reassignment call.”

27

ird, the Court upheld the

FCC’s use of a “reasonable means” standard for revocation of consent but left open the possibility

of dierent “revocation rules mutually adopted by contracting parties.”

28

After the D.C. Circuit’s decision, the FCC reconsidered how the TCPA applies to reassigned

numbers, issuing a proposed rule on preventing unwanted calls to reassigned numbers and seeking

comment on methods to establish a reassigned numbers database.

29

A reassigned numbers database

— long supported by market participants and consumer advocates — could reduce unwanted

calls to consumers and reduce caller liability by permitting callers to conduct due diligence to

learn whether a number has been recently reassigned and, if it has, remove that number from their

autodialed calls.

30

Fair Debt Collection Practices Act

Congress enacted the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), in part, to “eliminate abu-

sive debt collection practices by debt collectors.”

31

e responsibility of enforcement is shared by

the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (the Bureau) and the Federal Trade Commission

(FTC).

32

However, current implementation of the FDCPA may inadvertently make interactions

between debt collectors and consumers needlessly cumbersome. e FDCPA prohibits debt col-

lectors from disclosing information about a consumer’s debt to unauthorized third parties and

allows consumers to terminate communication about the debt.

33

While using e-mail or voicemail

to communicate with a consumer about his or her debt is permissible under FDCPA, potential

litigation risk can arise if the debt collector inadvertently discloses information regarding the debt

to an unauthorized third party while using contact information provided by the borrower. As a

result, even if consumers increasingly prefer to communicate digitally, such as via text messages and

e-mail, litigation risk can discourage debt collectors from doing so.

25. ACA International v. FCC, 885 F.3d 687 (D.C. Cir. 2018).

26.

Id. at 700.

27. Id. at 707.

28. Id. at 709-10.

29. Advanced Methods to Target and Eliminate Unlawful Robocalls (Apr. 20, 2018) [83 Fed. Reg. 17631 (Apr. 23,

2018)].

30.

Id.

31. 15 U.S.C. § 1692(e).

32. Id. § 1692l; see also Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection, Fair Debt Collection Practices Act: Annual

Report 2018 (Mar. 2018), at 7, available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/

cfpb_fdcpa_annual-report-congress_03-2018.pdf.

33. 15 U.S.C. § 1692c(b).

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Digitization

21

Recommendations

Treasury recognizes that the increasingly digitized nature of the economy and nancial system

requires revisiting of customer communication and disclosure rules that were designed primarily

for an era of physical mail and telephone calls. Treasury has identied some opportunities for

reform of the TCPA and FDCPA regulatory regimes but recommends that regulators proactively

identify other rules in need of revision.

Treasury recommends that the FCC continue its eorts to address the issue of unwanted calls

through the creation of a reassigned numbers database. Treasury recommends that the FCC create

a safe harbor for calls to reassigned numbers that provides callers a sucient opportunity to learn

that the number has been reassigned.

In addition, Treasury recommends that the FCC provide clear guidance on reasonable methods for

consumers to revoke consent under the TCPA.

Additionally, Congress should consider statutory changes to the TCPA to mitigate unwanted calls

to consumers and provide for a revocation standard similar to that provided under the FDCPA.

Treasury also recommends that the Bureau promulgate regulations under the FDCPA to codify that

reasonable digital communications, especially when they reect a consumer’s preferred method,

are appropriate for use in debt collection.

Closing the Digital Divide

“Digital divide” describes the gap between populations that have access to modern information

and communication technology and those that have no or limited access. e FCC estimates

30% of people living in rural America lack access to broadband compared to 2.1% of people

in urban areas, which means that nearly 24 million rural Americans cannot fully access the

benets of the digital economy.

34

Access to the digital economy allows Americans to benet

from the rapid growth of technology and innovation.

Broadband access has become increasingly important for economic opportunity, job creation,

education, and civic engagement. Rural communities have made large gains in adopting

technology, but substantial segments of rural America still lack the infrastructure needed for

high-speed internet, and any access that rural areas have is often slower than that of non-

rural areas.

35

In February 2017, the FCC took action designed to expand and preserve mobile

coverage across rural America and in tribal lands.

36

e FCC stated that the next stages of the

34. Federal Communications Commission, 2018 Broadband Deployment Report (Feb. 2, 2018), available at:

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-18-10A1.pdf.

35.

Andrew Perrin, Pew Research Center, Digital Gap Between Rural and Nonrural America Persists,

blog post (May 19, 2017), available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/19/

digital-gap-between-rural-and-nonrural-america-persists/.

36. Federal Communications Commission, In the Matter of Connect America Fund Universal Service Reform –

Mobility Fund, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (Feb. 23, 2017), available at:

https://apps.fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-17-11A1_Rcd.pdf.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Consumer Financial Data

22

Connect America Fund

37

will be implemented and will provide additional funding for rural

xed broadband over the next decade.

38

Additional support for these eorts is reected in Executive Order 13821, which states that

“it shall therefore be the policy of the executive branch to use all viable tools to accelerate the

deployment and adoption of aordable, reliable, modern, high-speed broadband connectivity

in rural America.”

39

Concurrently, the President instructed the Secretary of the Interior to

develop a plan to increase access to tower facilities and other infrastructure managed by the

Department of the Interior in rural America for broadband deployment.

40

Deployment of more infrastructure to support broadband in rural areas will help to close the

digital divide and assist more Americans in underserved communities to participate in the

digital economy and overcome geographic isolation.

Consumer Financial Data

As a result of digitization, vast amounts of data now exist in forms that can be readily aggregated

and analyzed with computing power. Online and mobile applications that draw on these data

make it possible for consumers to view banking and other nancial account information, often

held at dierent nancial institutions, on a single platform, monitor the performance of their

investments in real-time, compare nancial and investment products, and even make payments

or execute transactions. Applications can also assist with automatic savings, budget advice, credit

decisions, and fraud and identity theft detection in real-time.

41

In short, digitized record-keeping and these applications have exponentially improved a consumer’s

ability to make nancial decisions. It has given rise to a new sector of nonbank nancial institu-

tions focused on products and services utilizing data aggregation, based on data obtained with the

consumer’s consent. e rise of such nancial institutions presents questions regarding the way in

which they operate and are currently regulated.

37. The Connect America Fund, also known as the Universal Service High-Cost Fund, is the FCC’s program to

expand voice and broadband services for areas where they are unavailable.

38.

Federal Communications Commission, Connect America Fund Phase II Auction Scheduled for July 24, 2018 -

Notice and Filing Requirements and Other Procedures for Auction 903 (Feb. 1, 2018), available at: https://apps.

fcc.gov/edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-18-6A1.pdf.

39. Executive Order 13821, Streamlining and Expediting Requests to Locate Broadband Facilities in Rural

America (Jan. 8, 2018) [83 Fed. Reg. 1507 (Jan. 11, 2018)].

40.

Executive Office of the President, Supporting Broadband Tower Facilities in Rural America on Federal

Properties Managed by the Department of the Interior (Jan. 8, 2018) [83 Fed. Reg. 1511 (Jan. 12, 2018)].

41.

See Letter from the Center for Financial Services Innovation to the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection,

CFPB-2016-0048 Request for Information Regarding Consumer Access to Financial Records (Feb. 21,

2017), available at: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=CFPB-2016-0048-0047.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Consumer Financial Data

23

Data Aggregation

Data aggregation generally refers to any process in which information from one or more sources is

compiled and standardized into a summary form.

42

Often data are aggregated for specic business

or research purposes such as statistical analysis, performance tracking, or recordkeeping. As of the

end of June 2018, ve of the largest publicly-traded U.S. companies by market capitalization are

integral drivers of the digital economy and use data aggregation for telecommunications, logistics,

marketing, social media, and other purposes.

43

How Data Aggregation Works

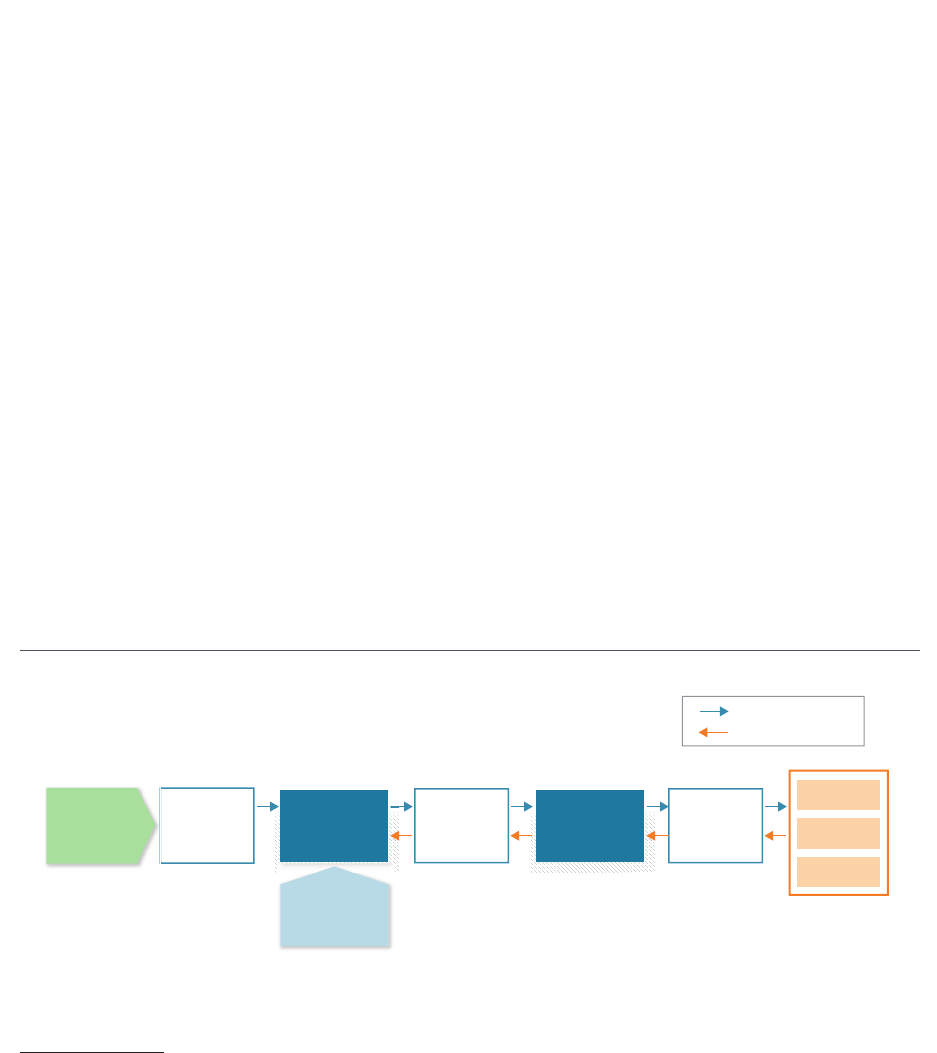

At the most basic level, data aggregation in the nancial services sector necessarily involves consum-

ers, nancial services rms, data aggregators, and consumer nancial technology (ntech) application

providers. “Consumers” are the individuals who are users of nancial services and the principal pro-

viders of the information collected by nancial service companies. In the consumer nancial services

data aggregation framework, consumers decide which applications to use in order to access their data,

give consent for that access, and provide necessary authentication (i.e., login) information.

“Financial services companies” or “nancial services rms” include banks, mutual funds, insurance

companies, broker-dealers, wealth management rms, and other nancial institutions that provide

traditional retail banking, depository, credit, brokerage, investment, and other account manage-

ment services to consumers. ese companies are the sources of consumer nancial account and

transaction data.

“Data aggregators” are the rms that access, aggregate, share, and store consumer nancial account

and transaction data they acquire through connections to nancial services companies. Aggregators

are intermediaries between the ntech applications that consumers use to access their data, on the

one hand, and the sources of data at nancial services companies on the other. An aggregator may

be a generic provider of data to consumer ntech application providers and other third parties, or

it may be part of a company providing branded and direct services to consumers.

Finally, “consumer ntech application providers” are the rms that access consumer nancial

account and transaction data, either from data aggregators or nancial services companies, in

order to provide value-added products and services to consumers. Consumers access these services

through “ntech applications” — i.e., the websites or mobile apps — created by these rms.

Consumer ntech application providers may also have direct links to nancial services companies

in order to, for example, provide direct services to a bank’s customers, access payments systems, or

facilitate credit origination.

Operationally, the key data aggregation processes involve acquiring, compiling, standardizing, and

disseminating consumer nancial data. Data aggregators may dier in the breadth and sophistica-

tion of the aggregation services they oer, and may specialize in dierent types of data or target a

42. See also Request for Information Regarding Consumer Access to Financial Records (Nov. 14, 2016) [81 Fed.

Reg. 83806, 83808-09 (Nov. 22, 2016)] (“Data Aggregation RFI”).

43.

These companies are Apple, Amazon, Alphabet [Google], Microsoft, and Facebook, based on Treasury analysis

of Bloomberg data.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Consumer Financial Data

24

specic developer base.

44

Some data aggregators may focus on aggregating nancial account bal-

ances, transactions data, or credit card activity, for example, or they may primarily support con-

sumer ntech application providers geared toward oering specic products (such as auto loans or

mortgages) or services (such as peer-to-peer payments or budget tracking).

44. For an account of the evolution of data aggregation services, see Michael Kitces, The Six Levels of Account

Aggregation #FinTech and PFM Portals for Financial Advisors, blog post (Oct. 9, 2017), available at: https://

www.kitces.com/blog/six-levels-account-aggregation-pfm-fintech-solutions-accounts-advice-automation/.

Figure 2: Participants in the Consumer Financial Services Data Aggregation Framework

Participant Description Role

Consumers • Individuals • Choose which fintech applications serve needs

• Accept terms and conditions

• Give consent for data sharing

• Provide login credentials or other information for

authentication

Data

aggregators

• Firms that aggregate consumer

financial data to share with other

third-parties, e.g. consumer fintech

application providers

• Firms that aggregate consumer

financial data to provide branded

and direct services to consumers

• Compile consumer financial account and

transaction data obtained (1) through consumer-

provided credentials (e.g., screen-scraping)

and/or (2) through authorized connections with

financial services companies (e.g., APIs)

• Provide data to consumer fintech application

providers and other third-parties

• May develop own fintech applications

• Often invisible to consumers

Consumer

fintech

application

providers

• Third-party firms offering value-

added financial products and

services to consumers

• Create and market fintech applications for

consumers

• Frequently rely on data from aggregators to run

applications

• Applications enable consumers to monitor

accounts, track budget and financial goals, pay

bills, make peer-to-peer payments, take out loans,

receive investment advice, etc.

Financial

services

companies

• Retail banks and other depository

institutions

• Retail broker-dealers

• Mutual fund companies

• Wealth management firms

• Insurance companies

• Other traditional financial

institutions

• Provide traditional banking, investment, insurance

and other financial services to consumers

• Sources of consumer financial account and

transaction data

• Data may be accessed directly (e.g., APIs) or

indirectly (e.g., screen-scraping)

Source: Treasury staff analysis.

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

Embracing Digitization, Data, and Technology • Consumer Financial Data

25

In general, data aggregators make data available by providing a platform on or through which con-

sumer ntech application providers can build and run their applications and provide an interface

with consumers. Because data aggregators are few in number compared to nancial services com-

panies — a relative handful versus thousands — and because they have generally sunk the costs of

connecting to nancial services companies, consumer ntech application providers only have to