The implementation of

Article 31 of the Treaty

on European Union and

the use of Qualified

Majority Voting

Towards a more effective Common Foreign

and Security Policy?

Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

Directorate-General for Internal Policies

PE 739.139 - November 2022

EN

STUDY

Requested by the AFCO committee

Abstract

This study has been commissioned by the European Parliament’s

Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

at the request of the AFCO Committee. It analyses the

possibilities and challenges regarding unanimity and qualified

majority voting as well as the use of passerelle clauses in EU

decision-making, with a special focus on the use of qualified

majority voting in the European Union’s Common Foreign and

Security Policy.

The implementation

of Article 31 of the

Treaty on European

Union and the use of

Qualified Majority

Voting

Towards a more effective Common

Foreign and Security Policy?

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Citizens' Rights and

Constitutional Affairs.

AUTHORS

Ramses A. WESSEL, Department of European and Economic Law, University of Groningen

Viktor SZÉP, Department of European and Economic Law, University of Groningen

ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE

Eeva PAVY

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Fabienne VAN DER ELST

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other

parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU internal

policies.

To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe for updates, please write to:

Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

Email: poldep-citizens@europarl.europa.eu

Manuscript completed in November 2022

© European Union, 2022

This document is available on the internet at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

© Cover image used under licence from Adobe Stock.com

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 3

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 5

LIST OF BOXES 7

LIST OF TABLES 7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8

1. INTRODUCTION 10

1.1. Political context for the push for a more efficient EU 11

1.2. The aim of this report 13

2. CURRENT EU INSTITUTIONAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL ARCHITECTURE 15

2.1. An institutional balance 15

2.2. European Council 16

2.3. Council 17

2.4. Commission 18

2.5. European Parliament 18

2.6. Court of Justice of the European Union 19

2.7. Decision-making procedures 20

3. MAKING THE EU MORE EFFECTIVE 24

3.1. The Conference on the Future of Europe and potential Treaty changes 24

3.2. Ordinary Treaty revision 27

3.3. Simplified revision procedure 31

3.3.1. Amending Part III of the TFEU 31

3.3.2. The two “general” passerelle clauses 34

3.4. Special passerelle clauses in non-CFSP matters 38

3.4.1. Social policy 39

3.4.2. Environmental policy 40

3.4.3. Family law with cross-border implications 40

3.4.4. Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 41

3.5. Enhanced cooperation in non-CFSP matters 42

4. UNDERSTANDING THE EU’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK ON EXTERNAL ACTION 43

4.1. QMV in EU external action: the nexus between CFSP and trade 50

4.2. The CFSP as a special field of EU external action 55

4.2.1. The role of Parliament in CFSP matters 57

4.3. Constructive abstention 60

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

4 PE 739.139

4.4. QMV in CFSP matters 63

4.4.1. Vetoes and delays 63

4.4.2. Political calls for QMV 65

4.4.3. Central Europe against QMV? 71

4.4.4. Current legal possibilities to use QMV in CFSP matters (Article 31(2) TEU) 73

4.4.5. Even more QMV options? The special CFSP passerelle clause (Article 31(3) TEU) 75

4.4.6. The advantages and challenges to extend QMV to CFSP matters 78

4.5. Enhanced cooperation in CFSP matters 79

5. RECOMMENDATIONS 81

6. CONCLUSIONS 84

REFERENCES 85

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 5

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AA Association Agreement

ACI

Anti-Coercion Instrument

AFCO

Committee on Constitutional Affairs of the European Parliament

AFET

Committee on Foreign Affairs of the European Parliament

AFSJ

Area of Freedom, Security and Justice

CCP Common Commercial Policy

CFSP

Common Foreign and Security Policy

CJEU

Court of Justice of the European Union

CoFE

Conference on the Future of Europe

CSDP Common Security and Defence Policy

EC

European Communities

ECB

European Central Bank

EEAS

European External Action Service

EMU Economic and Monetary Union

EP

European Parliament

EPC

European Political Cooperation

EU

European Union

EUGHRS

EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime

HR/VP

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/Vice-

President of the European Commission

IPC

Interparliamentary Committee Meeting

GAC

General Affairs Council

JHA Justice and Home Affairs

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

6 PE 739.139

FAC

Foreign Affairs Council

MEP

Members of the European Parliament

MP

Members of the Parliament

OLP

Ordinary Legislative Procedure

SEA

Single European Act

SLP

Special Legislative Procedure

TEU

Treaty on European Union

TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

QMV

Qualified Majority Voting

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 7

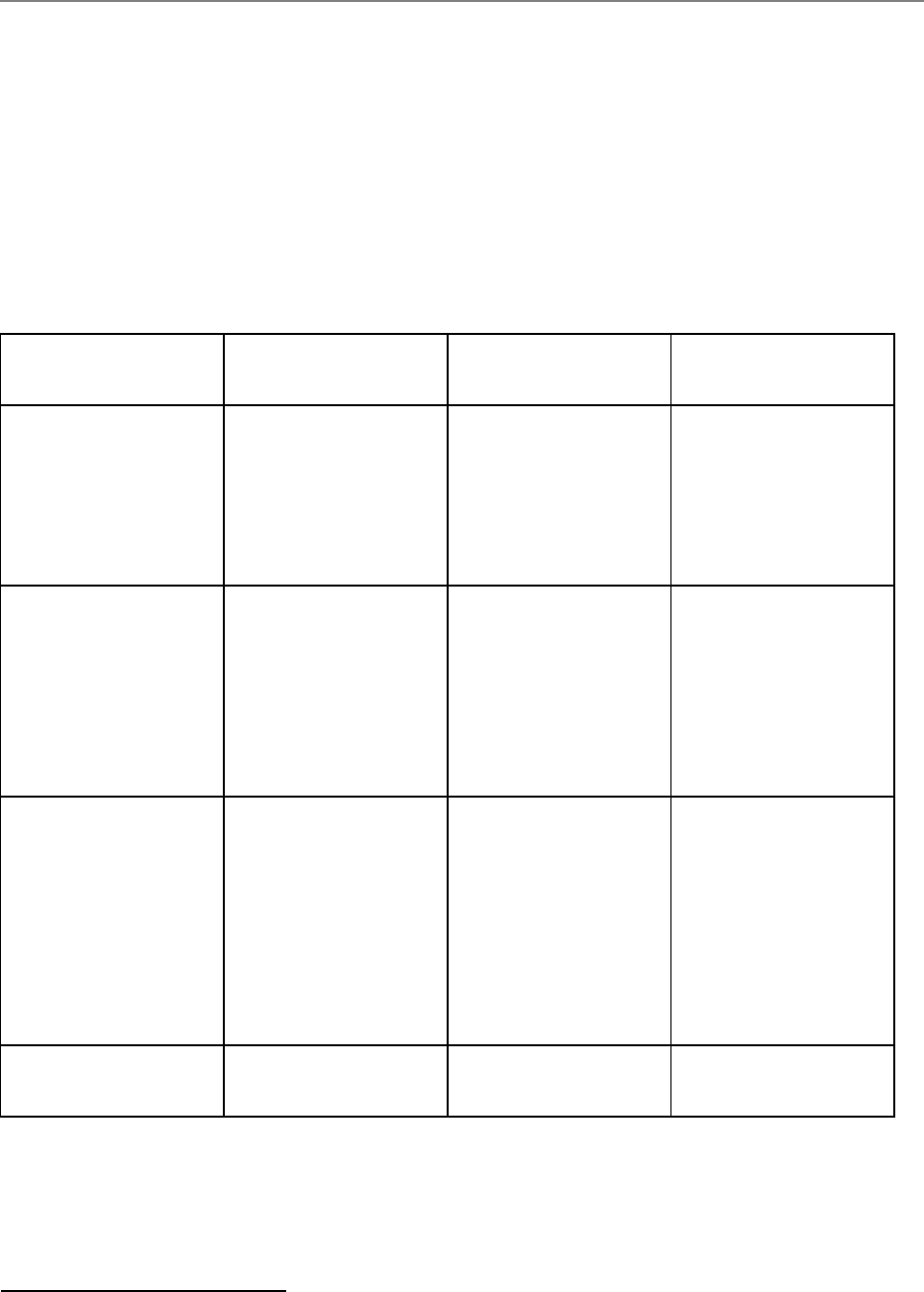

LIST OF BOXES

Box 1: Ordinary Treaty revision (own elaboration) 29

Box 2: Simplified revision procedure 33

Box 3. The general passerelle clauses 37

Box 4. A non-exhaustive list of vetoes, threats of veto and delays in CFSP matters 64

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: A summary on the special passerelle clauses in non-CFSP matters 38

Table 2. The Union’s split personality in its external action 45

Table 3. Major calls for QMV in CFSP matters (authors’ own elaboration) 65

Table 4. Existing QMV possibilities in CFSP matters 73

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

8 PE 739.139

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background

The history of the European Union (EU) has shown us that Member States have increasingly accepted

and codified the use of the qualified majority voting (QMV) in most policy areas. Indeed, QMV is now

the default rule in the Council of the EU (Council) when it adopts EU legislation. However, even after

the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, there remains certain areas of policymaking where QMV can

only be applied to a limited extent. For instance, the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is still

subject to “special rules and procedures” that include the requirement of unanimity. Although EU

Treaties provide for a limited set of options to use QMV in CFSP context, so far EU Member States have

been cautious to activate those provisions.

The requirement of unanimity has sometimes blocked the EU in its foreign and security policy actions

and has now created a general discontent towards the current CFSP decision-making rules. Indeed, in

the last couple of years (between mid-2016 and mid-2022), we observed 30 individual vetoes, threats

of veto or delays in CFSP context and, in the last decade or so (between mid-2013 and mid-2022), we

have also observed 25 major political calls, partly as a reaction to those blockages, to change CFSP

decision-making rules to avoid deadlock in decision-making. No wonder that the shift from unanimity

to QMV, especially in the field of the CFSP, is increasingly on the EU’s political agenda. This is mainly

due to the new types of challenges the EU faces, including Russia’s war in Ukraine, that require quick

and efficient decisions. In addition, the Conference on the Future of Europe (CoFE) has once again re-

opened policy discussions to remove the requirement of unanimity in most EU policy areas and in

particular in the CFSP. Indeed, the CoFE, for instance, recommended to use QMV in almost all areas of

EU policymaking. While EU institutions and Member States seem to be willing to serio u sly co nsid e r that

recommendation, they have diverging views on how to best translate that recommendation into

practice.

In fact, the CoFE recommendation to shift from unanimity to QMV in CFSP matters can be pursued in

several ways. The first option is to amend the EU Treaties. Under Article 48(2) – (5) of the Treaty on

European Union (TEU), any Member State government, the European Parliament (EP, Parliament) or

the European Commission (Commission) can submit proposals to change EU Treaties. Indeed, in June

2022, recognising that EU citizens want to see a more efficient EU, Parliament adopted a resolution

calling for a Convention for the revision of the Treaties. That resolution, among others, has called for

reforming voting procedures in the Council to enhance the EU’s capacity to act, including switching

from unanimity to QMV in areas such as sanctions. While amending the EU Treaties may indeed be a

solution to ease or possibly to remove the unanimity requirement in e.g. CFSP matters, experience

shows that such process certainly cannot be carried out overnight and usually involves a long

bargaining process between the Member States.

Another option for a wider application of QMV in CFSP context is to use the already existing Treaty

provisions to activate more efficient decision-making procedures. On the one hand, current EU Treaties

already provide for four cases in which the Council can adopt CFSP decisions by QMV. To some extent,

these QMV options are already being used, especially when the Council modifies already existing EU

sanctions regimes or when the Council appoints Special Representatives, but they have not been fully

used yet. On the other hand, existing QMV options can be further extended by the special CFSP

passerelle clause under Article 31(3) TEU. The activation of that passerelle clause is currently being

discussed in the General Affairs Council. EU affairs ministers have been relatively open to triggering

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 9

that provision, but the outcome of those negotiations is still uncertain and will probably not conclude

before the end of 2022/early 2023.

Although unanimity in CFSP matters clearly prevails, it should be emphasised that QMV is being used

in EU external action even in areas that have clear links to CFSP. In fact, there is an evolving interaction

between the different facets of EU external action that is manifested in several nexuses between CFSP

and non-CFSP areas. Nowadays, the Commission is more committed to apply, wherever it is possible, a

more holistic view of EU external action and use e.g. EU trade legal bases to promote CFSP objectives

where QMV applies. Examples of such actions include the Anti-Coercion Instrument, the new

framework for the screening of foreign direct investments, the Anti-Torture Regulation or the Forced

Labour Legislation. These show that in many cases the EU’s wide competences in trade matters may

not only help to contribute to a more effective EU external action in terms of voting procedures but

also in projecting EU power through commercial policy tools.

Yet another possibility not to block CFSP decisions is the wider use of constructive abstention under

Article 31(1) TEU. Although unanimity remains the dominant voting procedure in CFSP matters, it does

not imply that every Member State should vote in the affirmative if the Council seeks to adopt a CFSP

decision. Constructive abstention under the second subparagraph of Article 31(1) TEU allows a (small

group of) Member State(s) to abstain from a vote and decide not to apply a CFSP decision. Until the

beginning of Russia’s war in Ukraine, constructive abstention has been invoked in only one case in

2008. Since the 24

th

of February 2022, it has been once again triggered in the case of the European

Peace Facility (EPF) in relation to three Member States and also in the case of the setting up of a Military

Assistance Mission in support of Ukraine (EUMAM Ukraine) in relation to one Member State.

Although the European Council and the Council dominate the CFSP, Parliament can also influence it,

albeit to a more limited extent and perhaps in a more informal way. In fact, the EP but also other

parliaments have the ability to provide a forum for debate in foreign policy questions. Those debates

enhance the positions of the parliaments even in policy areas where formal competences are less

pronounced. This rather informal power can be used to question and even to force EU executives to

justify their (non-)actions in CFSP issues. Although the HR/VP or foreign ministers and their officials can

always refer to their prerogatives under current Treaty provisions and can emphasise their own

legitimate competences to shape EU-level foreign and security policy, the exposure to public opinion

can force EU executives to move in a direction which is more in line with the expectations of

parliaments. This is perhaps even more true in a policy area where the Council holds closed policy

debates. The role of the parliaments, whose members are directly elected by citizens, becomes even

more important as they can hold public debates on the outcome of foreign policy negotiations which

are kept otherwise in an “intergovernmental” format. In the case of the EU’s Global Human Rights

Sanctions Regime (EUGHRS), for instance, parliaments were quite successful in signalling their

preferences to adopt a sanctions regime.

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

10 PE 739.139

1. INTRODUCTION

1

This study was written upon a request from the Committee on Constitutional Affairs of the European

Parliament (AFCO Committee), following a request from Parliaments’ Policy Department for a study on

‘The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the use of Qualified

Majority Voting’. The reason for this being that the AFCO Committee needs expertise to assess the

implementation of Article 31 TEU and the use of qualified majority voting (QMV) on proposals from the

EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy / Vice-President of the Commission

(HR/VP; High Representative).

Article 31 TEU contains the decision-making procedure on the basis of which the Council adopts

decisions in the area of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). The “special rules and

procedures” that characterise CFSP include the default rule that CFSP decisions be taken by unanimity,

which stand in stark contrast to most other policy areas, where QMV has by now become the default

voting modality.

2

The study will thus contribute to the preparation of the AFCO Committee’s implementation report

entitled "Implementation of ‘

passerelle’ clauses in the EU Treaties”, which is likely to look also into the

implementation of Article 31 TEU, as well as to a wider discussion in the AFCO Committee on switching

from unanimity to QMV and the possible need for Treaty changes.

3

The aim of this study is to analyse the possibilities and challenges linked to unanimity and QMV as well

as the use of passerelle clauses in the EU decision-making, with a special focus on the use of QMV on

proposals from the EU HR/VP. Within that broader context, the study, in particular,

• Gives an overview of the EU's institutional and constitutional architecture, as regards

decision-making procedures and their challenges (unanimity, QMV, passerelle clauses);

• Looks into the need for mainstreaming QMV in the EU decision making procedures, taking

into account the recommendations adopted by the Conference on the Future of Europe

(CoFE);

• Analyses the concept of passerelle clauses and heir use in the EU decision-making in

general;

• Describes the decision-making procedures in the field of CFSP and, in this context,

investigates also the CoFE recommendation No 21;

• Analyses the use of Article 31 and the use of QMV on proposals from the HR/VP;

• Looks into the advantages and challenges of extending QMV to the CFSP;

• Gives policy recommendations on how to improve the EU decision-making in general and

in the field of CFSP and, more specifically, whether the shift from unanimity to QMV, either

via passerelle clauses or through Treaty changes, would be a sustainable solution for this.

1

Dr. Viktor Szép is a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of European and Economic Law of the University of

Groningen. Prof. Dr. Ramses A. Wessel is Professor of European Law at that same department. The authors wish to thank

Marcell Szilágyi, student at the University of Groningen, for his assistance on this report during an internship, and to Ben

Whyte for proofreading the document in its entirety. Any remaining mistakes are the authors’ responsibility.

2

Other areas where decisions are adopted by unanimity are taxation, social security or social protection, the accession of

new countries to the EU and operational police cooperation. See

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-

content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0647&from=EN.

3

AFCO has recently started to prepare AFCO/9/10045 2022/2142(INI) Implementation report: Implementation of

“passerelle” clauses in the EU Treaties. Rapporteur: Giuliano Pisapia (S&D)

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 11

1.1.

Political context for the push for a more efficient EU

This request from the AFCO Committee could not have come at a better time. The topic of efficient

decision-making in EU foreign and security policy is high on the political agenda. While the question of

how to improve the efficiency in this area is not new, the current situation – in the words of

Commissioner Thierry Breton – is an era of “perma-crisis” that may require renewed attention to more

efficient decision-making procedures. The global pandemic, climate change and the brutal war of

aggression at our doorstep underlines the urgency of assessing new options.

4

Indeed, it is well known

that EU integration advances faster when crises hit. As Jean Monnet famously said, the Union will be

“forged in crises and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises”. Geopolitics has re-

entered the EU’s political agenda,

5

and the EU is re-investing in the relationship with its neighbours.

This is exemplified by the first meeting of the European Political Community that took place on 6

October 2022 in Prague.

6

Simultaneously, world politics has fragmented in the last couple of years.

Strategic supply chains and technological competition have become a political priority. Supply chains

and our dependence on them are increasingly used as weapons.

7

These recent developments have triggered a renewed discussion about how to make the Union's

external action more effective, including its CFSP. In late August 2022, seeking to improve the resilience

and governance of the EU, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced his intention to significantly alter

the EU’s functioning. He argued that “[e]ven the European treaties are not set in stone [and their] rules

can be changed – in the very short order if need be”. He further added that “[i]f together we come to

the conclusion that the Treaties need to be amended so that Europe makes progress, then we should

do that”. Chancellor Scholz also referred to the CoFE, the outcome of which showed that “the public

wants an EU that delivers”. His reform proposals include in particular a shift from unanimity voting to

QMV in not just sanctions policy and human rights issues, but also in foreign and tax policy. Chancellor

Scholz concluded that “the alternative to QMV, such as a new system of opt-ins and opt-outs – would

just weaken EU unity”.

8

As will be outlined further in this report, Chancellor Scholz was not the first to suggest making more

use of QMV in foreign policy. It has been mentioned surprisingly often in the last years by prominent

politicians. Among many others to which we will return later in this report, Commission President

4

Thierry Breton, ‘Sovereignty, self-assurance and solidarity’ (European Commission - European Commission, 2022)

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/speech_22_5350

accessed 25 October 2022.

5

See also the new Brussels Institute for Geopolitics, that was launched in Prague with the support of the Netherlands,

France and Germany; https://big-europe.eu/

.

6

European Council, ‘Meeting of the European Political Community - October 2022’ (2022)

https://newsroom.consilium.europa.eu/events/20221006-meeting-of-the-european-political-community-october-2022

accessed 20 October 2022.

7

Thierry Breton, ‘Neither Autarchy nor Dependence – More European Autonomy’ (European Commission - European

Commission, 2022) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_5173

accessed 20 October

2022.

8

EurActiv, ‘European Treaties 'aren’t Set in Stone’, Says Scholz’ (www.euractiv.com, 29 August 2022)

https://www.euractiv.com/section/future-eu/news/european-treaties-arent-set-in-stone-says-scholz/

accessed 29

August 2022; Financial Times, ‘Olaf Scholz Outlines New EU Vision with Call for European Air Defence Scheme’ Financial

Times (29 August 2022); EUobserver, ‘Scholz Wants Majority Voting for EU Sanctions’ (EUobserver)

https://euobserver.com/news/155893> accessed 30 August 2022.

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

12 PE 739.139

Ursula von der Leyen, in her first State of the Union speech, proposed introducing QMV in decisions

concerning human rights and sanctions. She pointed to “a clear need for Europe to take clear positions

and quick actions on global affairs” and asked: “But what holds us back? Why are even simple

statements on EU values delayed, watered down, or held hostage for other motives? When Member

States say Europe is too slow, I say to them be courageous and finally move to qualified majority voting

– at least on human rights and sanctions implementation.”

9

This idea had been introduced by her

predecessor, Jean-Claude Juncker in 2017.

10

The discussion was echoed by the leaders of France and

Germany in their 2018 Meseberg Declaration,

11

as well as by other member States.

12

Parliament had

also prepared a brief on the matter.

13

Thus, over the past years, the issue of QMV in CFSP has suddenly

and prominently re-entered political discourse.

French President Emmanuel Macron also referred to the increasing difficulties Europe faces. In August

2022, during a cabinet meeting at the Elysée Palace, President Macron warned them to be ready for

sacrifices, as Europe faces “the end of abundance”. He considered that Europe is going "through […] a

big shift, a big upheaval […] a series of serious crises”, including the war in Ukraine and unprecedented

droughts due to climate change. France and Europe are expected to face difficulties in public finance,

resource shortages, and breakdowns in supply chains.

14

"This overview that I'm giving − the end of

abundance, the end of nonchalance, the end of assumptions − it's ultimately a tipping point that we

are going through that can lead our citizens to feel a lot of anxiety […] [o]ur system based on freedom

in which we have become used to living, sometimes when we need to defend it, it can entail making

sacrifices."

15

This new situation may also require more effective EU decision-making procedures.

HR/VP Josep Borrell rightly argued that the “EU sometimes struggles to take decisions on foreign policy

due to divisions among Member States. And yet many want the EU to play a stronger, geo-political role

in a dangerous world. We need an honest debate without taboos on how best to achieve this, including

9

European Commission (2020) State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen at the European Parliament

Plenary, Brussels 16 September 2020. See also the President's more recent speech in which she proposed to “improve

the way we do things and the way we decide things”; Ursula von der Leyen, ‘State of the Union Address 2022’ (European

Commission - European Commission).

10

European Commission (2017) State of the Union Address by President Juncker, Brussels 13 September 2017. This lead to

the Communication from the Commission to the European Council, the European Parliament and the Council, “A

stronger global actor: a more efficient decision-making for EU Common Foreign and Security Policy”, COM (2018) 647

final.

11

Meseberg Declaration, Renewing Europe’s promises of security and prosperity, A joint Franco-German declaration

adopted during the Franco-German Council of Ministers, which took place 19 June 2018 in Meseberg, Germany;

https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/germany/events/article/europe-franco-german-declaration-19-06-18

.

12

See the Non-paper by Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland,

Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden on

strengthening the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy ahead of the informal lunch discussion at the Foreign

Affairs Council on December 9, 2019.

13

European Parliament (2021) Qualified majority voting in foreign and security policy. Pros and Cons, Briefing, European

Parliamentary Research Service.

14

Reuters, ‘Macron Warns French Sacrifices Will Be Needed as Tough Winter Looms’ (2022)

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/macron-warns-french-sacrifices-will-be-needed-tough-winter-looms-2022-08-

24/ accessed 25 October 2022.

15

Le Monde, ‘Macron Warns France Faces “sacrifices” after “End of Abundance”’ (2022)

https://www.lemonde.fr/en/politics/article/2022/08/24/macron-warns-france-faces-sacrifices-after-end-of-

abundance_5994602_5.html accessed 25 October 2022.

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 13

on how we take decisions”.

16

HR/VP Borrell identified history, geography, and identity as the main

reasons for disunity in CFSP matters and believes that the long-term answer lies in the creation of a

common strategic culture that would allow the Member States to see the world from a common

viewpoint. HR/VP Borrell also added that while unanimity is the basic voting rule in CFSP context, QMV

is used in other areas of EU policymaking and “crucially, market rules or climate targets are not

secondary issues of lesser sensitivity. Indeed, big national interests are at stake, which often clash just

as much as in foreign policy”. He concluded that the mere existence of QMV would create an incentive

for the Member States to search for a common ground. Ideas to forge a common strategic culture –

including establishing a European Diplomatic Academy

17

– can be read in that context.

18

1.2. The aim of this report

The main aim of this report is to map the current legal and political options for using QMV in CFSP. In

doing so, the report distinguishes between current possibilities and proposed options that would

require a treaty change. Indeed, the latter option does no longer seem to be a taboo. The CoFE, in

explaining its goal and function, explicitly used the following quote by Commission President Von der

Leyen when addressing EU citizens:

“You have told us that you want to build a better future by living up to the most enduring promises of the

past. Promises of peace and prosperity, fairness, and progress; of a Europe that is social and sustainable, that

is caring and daring. You have told us where you want this Europe to go. And it is now up to us to take the

most direct way there, either by using the full limits of what we can do within the Treaties, or by changing

the Treaties if need be.”

19

In assessing potential options, this report does not limit itself to the area of foreign and security policy

but refers to existing options in other policy areas as well. In presenting any legal options, it takes the

political context of these matters into consideration. Improvement of the effectiveness of CFSP is also

the topic of two extensive EU Horizon 2020 research projects: Understanding and Strengthening EU

Foreign and Security Policy in a Complex and Contested World (JOINT) and Envisioning a New Governanc e

Architecture for a Global Europe (ENGAGE).

20

In these two projects, several academic institutions and

think tanks work together in analysing options for improving EU foreign policy effectiveness. The

present authors are members of the ENGAGE network.

Parliament has an important role to play. It is necessary to stress that the Treaties clearly indicate that

the CFSP is a Union policy that is to be supported by the Member States. Despite its formally limited

role in CFSP, the EP has always acknowledged the fact that CFSP is part and parcel of the Union’s

16

Josep Borrell, ‘When Member States Are Divided, How Do We Ensure Europe Is Able to Act?’ (2020)

https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/when-member-states-are-divided-how-do-we -ensure-europe-able-act-0_en

>

accessed 5 October 2022.

17

See the proposal by the European Parliament to that end: https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/own-

academy-could-help-eus-diplomatic-service-find-its-footing/

18

Compare HR/VP Borrell’s blog, which also clearly has this aim: “With this blog, I intend to take a step back and contribute

to building a European common strategic culture. The responsibilities of the HR/VP do not always allow me to speak out

as clearly as I would like”. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/window-world-blog-hrvp-josep-borrell_en

19

Ursula von der Leyen, ‘Closing Event of the Conference on the Future of Europe’ (European Commission - European

Commission, 2022) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_22_2944

accessed 20 October 2022.

20

Respectively https://www.jointproject.eu/ and https://www.engage-eu.eu/.

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

14 PE 739.139

(external) policies and has taken its role seriously by using all available means at its disposal to pro-

actively influence CFSP. In fact, despite the restraints it has faced, Parliament is often regarded as one

of the most active parliaments in the world where foreign policy is concerned.

21

The present report aims to provide further tools in that respect by explaining the current rules on EU

decision-making and existing, but underutilised, possibilities that are already offered by the Treaties

and potential new scenarios. As will be seen, there are pros and cons to a shift to QMV in CFSP. The

main challenge appears to be maintaining the idea of a Common Foreign and Security Policy while

facilitating the decision-making process. However, in many other equally sensitive policy areas, the EU

has shown itself to be able balance maintaining a common policy and acknowledging variations in

Member State’s perspectives. The coming paragraphs will show how this can be attained in CFSP as

well.

21

Compare R.A. Wessel, ‘Legal Aspects of Parliamentary Oversight in EU Foreign and Security Policy’, in Juan Santos Vara

and Soledad R. Sánchez-Tabernero (Eds.), The Democratisation of EU International Relations through EU Law, London/New

York: Routledge, 2018, pp. 135-154.

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 15

2. CURRENT EU INSTITUTIONAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL

ARCHITECTURE

QMV has by now become the default voting mechanism in the Council, except for CFSP where

unanimity is still the norm.

22

The 2009 Lisbon Treaty led to a further integration of CFSP into the Union's

legal framework, and subsequently allowed the Court of Justice to deal with many CFSP-related

questions. However, despite this, decision-making procedures still differ and often stand in the way of

integrating CFSP and other external policy elements into a coherent EU foreign policy.

In the following section, as a reminder of the roles of the various EU Institutions in the decision-making

process, this report will briefly summarise the EU's institutional and constitutional architecture. This will

facilitate a better understanding of the proposed changes made by the CoFE later on.

2.1. An institutional balance

When discussing the democratic legitimacy of the Union, comparisons are often made with the political

structure of Member States. Several shortcomings can indeed be noted, such as:

• a Parliament that does not have the final word in all cases;

• a Commission whose members cannot be sent home individually by a parliament;

• a Council (of Ministers) that is prepared to delegate matters to the Commission, but at the same

time wants to retain power as much as possible for the Member States through special

committees;

• a European Council in which the Heads of State or Governments can take far-reaching decisions

unimpeded by any scrutiny.

Seen in this way, the institutional structure of the Union is not set up according to the democratic rules

of the art. Yet even in this structure there is a balance of power, which is again the result of a

compromise. This compromise dates from the period of negotiations on the Treaty on the European

Coal and Steel Community when the establishment of an independent Commission (then called the

'High Authority') served to counterbalance the Council in which the interests of the individual member

states could emerge. This structure laid the foundations for an institutional balance that is still an

important part of the European Union and the current debate about the decision-making procedures.

In discussions about the composition of the Commission, the weighting of votes in the Council, or the

application of the legislative procedure before the European Parliament, this balance plays an

important role.

The structure is clear: the Commission is an independent body, which focuses on the interests of the

European Union as a whole. This makes it possible, irrespective of the individual interests of the

Member States, to take decisions in the interest of the entire Union. Here we clearly see the supra-

national element. The Council then represents national interests. In this way decisions can be made

22

Art. 24(1) TEU: "The common foreign and security policy is subject to specific rules and procedures. It shall be defined

and implemented by the European Council and the Council acting unanimously, except where the Treaties provide

otherwise".

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

16 PE 739.139

that consider the varying national preferences. The democratic dimension is reflected in the powers of

the European Parliament, which as a directly elected body, aims to increase the legitimacy of European

governance. Finally, the Court of Justice has the task of assessing the lawfulness of the implementation

of the treaties. These bodies – Parliament, the Council, the Commission and the Court of Justice –

alongside the European Central Bank and the European Court of Auditors, which monitor the

expenditure of the Union's own financial resources, are referred to as the 'institutions' by Article 13 TEU.

The institutions have powers in all Union policies. Article 13 of the Union Treaty refers in this regard to

“a single institutional framework aimed at promoting its values, pursuing its objectives, serving its

interests and the interests of its citizens and of the Member States, and ensuring consistency, ensure

the effectiveness and continuity of its policies and actions.”

2.2. European Council

The European Council meets at least four times a year.

23

This is the highest policy-making body of the

EU. The European Council is composed of the Heads of State or Governments of the Member Stat es, its

President, and the President of the Commission. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign

Affairs and Security Policy takes part in the work of the European Council. The members of the

European Council may decide to be assisted each by a minister and, in the case of the President of the

Commission, by a member of the Commission. The constitutional law of the individual member states

determines whether the head of state or government has a seat in the European Council. Despite the

current treaty basis in Article 18 TEU, the European Council was informally established in 1974 and only

legally enshrined in the Single European Act in 1986. The European Council can be regarded as an

institutionalisation of the summits that were previously organized ad hoc, but their origin is becoming

less and less apparent. In earlier days, meetings of the European Council usually took place in attractive

locations in the Member States. However, since the most recent enlargement of the Union, the

meetings have primarily taken place in Brussels, in order to take advantage of the security and

translation facilities present. The idea of the European Council as a traveling circus – for which every

organizing Member State had to make enormous efforts in the field of security, translation and

communication – has disappeared. The European Council is now more clearly integrated into the

'institutional framework' of the European Union. The President of the European Council no longer

exercises a national mandate but protects the Union's interests. From a legal standpoint, the European

Council must therefore be distinguished from the Member States as it has its own mandate under

Union law.

Without dealing with legislation, the European Council provides important impetus for the Union’s

development and defines the broad political guidelines and priorities.

24

In addition, the European

Council has some specific powers, such as to identify a breach by a Member State of the values on

which the Union is founded (Article 7 TEU), to change the size and composition of the Commission

(Article 17 TEU), setting priorities in the field of foreign and security policy (e.g. Articles 22, 24, 26 TEU)

and the area of freedom, security and justice (Article 68 TEU), treaty revision procedures (Article 48 TEU),

broad guidelines on economic policy (Article 121 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European

23

Article 15(3) TEU.

24

Article 15 TEU.

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 17

Union (TFEU)), or the monetary system (Article 141 TFEU). The outcomes of the European Council are

reflected in decisions, often presented as 'conclusions', which are in principle adopted by unanimity,

although in exceptional cases majority decision-making also takes place (Articles 235-236 TFEU). An

example of the latter is the election of the permanent Chair for two and a half years.

2.3. Council

The Council of the European Union is also referred to as the Council or the Council of Ministers. This

Council is the main decision-making body of the EU. Under Article 16 TEU, the Council exercises

legislative and budgetary functions together with the European Parliament. The Council is responsible

on the one hand for coordinating the economic policies of the Member States (Article 16(1) TEU) and

on the other hand holds decision-making power, the implementation of which can be entrusted to the

Commission (Article 290 TFEU).

In the Council, each Member State has a representative. Although in practice these are ministers, Article

16 TEU refers to representatives of the Member States at ministerial level who are authorized to bind

the government of the Member State concerned. This means that not only can ministers of sub-state

governments be delegated, but that it can also be the Heads of State or Government. The actual

composition of the Council varies with the subject on the agenda. Traditionally, the Council was the

domain of the foreign ministers. Due to its general character, this Foreign Affairs Council (FAC) is still

the most important when it comes to foreign policy issues. General institutional issues are discussed in

the General Affairs Council, which often consists of ministers or state secretaries for European Affairs.

In addition, most ministries have 'specialist councils'. There are currently ten Council configurations.

The meeting frequency differs per Council. A different classification can be chosen based on Article 236

TFEU.

Despite the changing formations, in a legal sense it is always the same institution. This is apparent, for

example, from the fact that decisions in all areas can be taken by all Council formations. This is possible

because many decisions are only on the Council's agenda as a formal final step in the process. This

'rubber stamping' (so-called 'A points' on the agenda) are possible because an agreement had already

been reached in the preliminary phase. As a result, no substantive consultation is necessary, and any

Council formation may act as a decision-making body. Although the Council is not in permanent

session, the Union has a Committee of Permanent Representatives in which the Member States each

have a representative at the ambassadorial level. This COREPER (Comité des représentants permanents)

prepares Council meetings (Articles 240 TFEU and 16(7) TEU). Before draft decisions are submitted to

COREPER, they are prepared by thematic working groups composed of national officials.

The Council is assisted by a secretariat, headed by a Secretary-General (Article 240(2) TFEU) and chaired

by one of its members. The Foreign Affairs Council is chaired by the High Representative of the Union

for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The latter function has clearly gained in importance since the

Treaty of Lisbon. Not only is the HR/VP the Union's main external representative in the world, but it is

also a member (and one of the Vice-Presidents) of the Commission, making the person in office the

linchpin of any foreign policy stances of the Union (Articles 18 et seq. TEU and the provisions on

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

18 PE 739.139

external relations in the TFEU). It is perhaps ironic that the Council dealing with what is often perceived

as the most intergovernmental area, foreign policy, is the only Council chaired by an EU official.

25

2.4. Commission

The European Commission is also referred to as the Union body par excellence. After all, the Commission

consists of independent persons who do not act on behalf of a Member State, but who must put the

interests of the European Union first. On 1 November 2004, the first new Commission took office

following the recent enlargement of the European Union. The Commission currently consists of

twenty-seven independent persons (Article 17 TEU), following a 2013 European Council decision

ensuring that the number of members of the Commission would correspond to the number of Member

States.

The tasks and powers of the Commission are multifaceted. The Commission has independent decision-

making power on a limited number of points (the so-called original powers). In addition, the

Commission has several powers delegated to it by the Council (the so-called delegated powers). The

development and role of these committees has been called "the comitology issue". This criticism stems

from fact that the Council grants the commission delegated powers, but maintains a 'vice like grip'

through national representatives who have a strong influence on these committees.

Importantly, the Commission has the right of initiative (Articles 17(1) TEU and 289 TFEU). This means

that in most cases where the Council and the European Parliament are jointly empowered to take

decisions, a Commission proposal is a prerequisite for any decision to be taken.

26

Finally, the

Commission plays a key role in monitoring compliance with Union law (Article 258 TFEU). The latter

two powers are often mentioned when reference is made to the distinctive character of the European

Union in relation to other international organisations. This is not entirely unjustified. As noted, the

Commission is the main Union body capable and empowered to rise above the interests of individual

Member States and to initiate decisions that primarily concern the achievement of the objectives of

the entire Union. As such, the Commission is also more neutral and can be trusted to be above national

power games. This is expressed, for example, in the Commission's aforementioned supervision of

compliance with European legislation by the Member States or even its fellow institutions.

2.5. European Parliament

The European Parliament consists of 705 members who have been directly elected since 1979, for a

period of five years (Article 14(2) TEU). The distribution of seats is based on more or less proportional

representation with a minimum number of seats for small states. Despite the national party-political

dimension in the composition of the Parliament (voters vote on lists of national parties), MEPs operate

within delegations which, once in Brussels, merge into multi-national political groupings. In other

25

This status of the High Representative was recently confirmed by the Court in Case T-125/22; Order of the President of

the General Court of 30 March 2022; ECLI:EU:T:2022:483.

26

Note, however, Parliament’s recent resolution in which it calls for a “general direct right of legislative initiative” to be

established for the EP. See EP resolution of 9 June 2022 on Parliament’s right of initiative (2020/2132(INI)).

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 19

words: despite the absence of European political parties that can be elected, the European Parliament

is underpinned by cooperation between like-minded people from other Member States. Although

there is no question of representation of a single 'European people', the MEPs are 'representatives of

the citizens of the Union' (Article 14(2) TEU).

Parliament's powers are, according to many, too limited and are therefore always a subject of

discussion. Nevertheless, Parliament has grown from an institution that in its early years only acted as

an advisory body, to an important co-legislative body. However, given the turnout percentages in

European elections, voters do not seem completely convinced yet. In 2009, the overall turnout was at

43%, down from 45.5% in 2004. This may be changing however, as the 2019 election saw turnout

increase to its highest level since 1994, at 51%.

In summary, the main powers of Parliament are the following:

• Depending on the subject: co-deciding or advising on new legislation (see below);

• Agreeing to enlargement treaties or association agreements;

• Exercising control over the Commission's policies;

• Adopting the budget together with the Council.

The latter power was used by Parliament to acquire a more prominent role (also referred to as 'the

power of the purse') even in areas where it only had an advisory role (such as foreign and security

policy). The control of the Commission is supported by Parliament's power to dismiss the Commission

as a whole (Article 234 TFEU). However, this drastic measure has never been used. This is largely due to

the existence of a number of 'safety valves'. For example, the vote on a resignation motion is public

(and the opinion of individual parliamentarian is visible to all), voting takes place under an increased

majority (two-thirds of the number of votes cast and a majority of the number of parliamentarians) and

provision is made for a 'cooling off period' of three days between the submission of the motion and the

vote. Resignation motions have thus far failed, although in 1999, following a report on financial

mismanagement and nepotism, the Commission decided to pre-emptively resign. This was because

otherwise a motion by Parliament would certainly have been adopted.

2.6. Court of Justice of the European Union

It can be said without exaggeration that without the presence of the Court of Justice, the EU wo uld not

have reached the level of integration we know today. Many provisions in the treaties and in

implementing legislation can only be properly valued by using the interpretations given by the Court.

Many legal regimes – like those regarding the external relations of the EU or the internal market – have

been shaped to a significant extent by case law of the Court.

The Court of Justice of the European Union, or CJEU, consists of two bodies. The Court of Justice, with

one judge from each state, and the General Court, with two members from each state. According to

Article 19, the court ensures “observance of the law in the interpretation and application of the

Treaties”.

The Court has several facets and is difficult to compare to a national court. An important role is reserved

for the Court as a uniform interpreter, in which it renders judgments on the validity and interpretation

of European law (Articles 19(3) TEU and 267 TFEU). The underlying idea is that EU law should not differ

from Member State to Member State and that citizens from Finland to Greece, Slovakia to Ireland have

same rights. However, the other aspects of the Court are no less important.

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

20 PE 739.139

For example, the Court has, under certain conditions, jurisdiction to:

• Settle disputes between the Commission and the Member States and the Member States

themselves (the 'infringement procedure', Article 258-260 TFEU);

• The annulment of acts of the institutions (the 'action for annulment', Article 263 TFEU); and

• Establish a violation of the Treaty in the event of the institutions failing to take a decision (the

'action for failure to act' Article 265 TFEU).

The Court also has jurisdiction to:

• Make an appeal in case of administrative sanctions (Article 261 TFEU);

• Determine the compatibility with the Treaty of treaties concluded by the Union or the Member

States (Article 218(11) TFEU);

• Determine the non-contractual liability of the Union and related damages (Article 268 in

conjunction with 340 TFEU);

• Rule under an arbitration clause in an agreement to which the Union is a party (Article 272

TFEU);

• Settle disputes between Member States related to the subject matter of the Treaty (Article 273

TFEU).

As a compromise between Continental and 'Common Law', the option of disclosing the differing

opinions of the various judges (dissenting opinions) has not been chosen, but a prior opinion

('conclusion') by one of the eleven advocates-general was opted for (Article 252 EC). With this system,

the Court aims to provide an impartial and often more academic and detached view of a particular

dispute. The Court is not obliged to follow the conclusion of the advocate-general, and it does

occasionally deviate with reasons, which increases the transparency of the case law.

In principle, the General Court has jurisdiction to hear all direct actions in the first instance. Citizens and

businesses will also mainly have to deal with the General Court. This is the first place to go to for actions

for annulment of decisions, for failure to take a decision and for damages in the event of Community

liability. Based on Article 256(1) TFEU, judgments of the General Court can be appealed to the Court of

Justice in matters of law.

2.7. Decision-making procedures

Decision-making in the EU largely takes place on the basis of either of the two legislative procedures:

the ordinary legislative procedure and the special legislative procedures. These apply to most policy areas.

When regulations, directives or decisions are adopted under the legislative procedures, the resulting

legal acts are to be regarded as 'legislative acts' (Article 289 TFEU). The most common procedure is the

'ordinary legislative procedure' where the Council takes a decision together with the European

Parliament on the initiative of the Commission. Where, in a particular policy area, the Treaty provides

that the Council shall act 'under the ordinary legislative procedure', Article 294 TFEU applies. The

ordinary legislative procedure broadly corresponds to what was referred to as the co-decision

procedure before the Lisbon Treaty. In short, the procedure entails that the Commission submits a

proposal for new legislation to the European Parliament and the Council. The latter can adopt the

decision, by qualified majority, if there is agreement on this with Parliament. If the Council and

Parliament do not agree on the draft decision, agreement can be reached via a so-called conciliation

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 21

committee in which representatives of both institutions try to reach a compromise. This result can then

be adopted by the Council (by qualified majority) and Parliament (by absolute majority). Or not, in

which exceptional case the Commission will have to produce an adapted proposal.

On the basis of Article 16(4) TEU, QMV is defined as at least 55% of the members of the Council,

comprising at least fifteen of them and representing Member States comprising at least 65% of the

population of the Union. A blocking minority must include at least four Council members, failing which

the QMV shall be deemed attained. The other arrangements governing QMV are laid down in Article

238(2) TFEU. The latter provides that by way of derogation from Article 16(4) TEU, where the Council

does not act on a proposal from the Commission or the HR/VP, QMV shall be defined as at least 72% of

the members of the Council, representing Member States comprising at least 65% of the population of

the Union. Article 238(3) TFEU further provides that where not all the members of the Council

participate in voting, QMV shall defined – on the basis of Article 238(3)(a) TFEU – in a same manner as

in Article 16(4) TEU but the blocking minority must include at least the minimum number of Council

members representing more than 35% of the population of the participating Member States, plus one

member, failing which QMV shall be deemed attained. Article 283(3)(b) TFEU further adds that by way

of derogation from Article 238(3)(a) TFEU, where the Council does not act on a proposal from the

Commission or from the HR/VP, QMV shall be defined as at least 72% of the members of the Council

representing the participating Member States, comprising at least 65% of the population of these

states.

In some cases, a 'special legislative procedure' applies. This variant cannot be found unambiguously in

the treaties and differs per policy area. Examples can be found regarding measures in the field of

discrimination (Article 19 TFEU), European citizenship (Article 21–23(3) TFEU), or the liberalisation of

capital movements (Article 64(3) TFEU). Special procedures also apply for the amendment of the

treaties and the accession of new Member States (Articles 48–40 TEU).

The role of Parliament has significantly increased compared to the past, in particular due to the general

application of the ordinary legislative procedure. This procedure now also applies in sensitive policy

areas such as asylum, immigration, and criminal law. Since the Lisbon Treaty, Parliament also has a right

of co-decision in the field of agriculture and fisheries (Article 43(2) TFEU).

The only EU policy area not reflected in the TFEU is the Common Foreign, Security and Defence Policy.

27

For political reasons, it was decided not to include this policy area in the TFEU, but to leave it in the TEU.

This choice can be explained by the origin of the policy area. The CFSP was already excluded from the

EC Treaty in the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 to allow the Member States to retain influence over the

policy. In the European Union that was established with the Maastricht Treaty, the CFSP was one of the

'pillars', alongside the Community pillar (EC law) and cooperation in the field of Justice and Home

Affairs. The intergovernmental decision-making model that characterised the CFSP at that time is still

recognizable in the current arrangements found in Title V, Chapter 2 of the Union Treaty. The same

goes for the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), which was introduced in the Treaty of Nice

in 2001 as the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) and is now found in Title V, Chapter 3 of

the TEU.

There are significant differences regarding the procedures. Most notably, the legislative procedure

cannot be used for the adoption of CFSP and CSDP decisions (cf. Article 24 TEU). In that sense, the

decisions cannot be regarded as legislative acts. There is also a clear difference concerning the role of

27

Next to the related European Neighbourhood Policy.

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

22 PE 739.139

the institutions. Further, with regard to the CFSP and CSDP, the Council is the main decision-making

body, but unlike most other Union policies, the Commission is not the driver of new policies here.

Article 30(1) TEU mentions in this respect the general rule that “any Member State, the High

Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, or the High Representative with the

support of the Commission”, may submit proposals to the Council. So far, the Commission has

remained aloof from initiating CFSP policy, but the possibility to present proposals together with the

High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy (HR) may change this.

What also plays a role is that the person holding the position of HR is also a member (and even Vice-

President) of the Commission (Article 17, paragraphs 4 and 5). The HR's role is clearly 'upgraded' in the

Lisbon Treaty. It can safely be said that the HR is the most important person in the field of external

relations because of his/her pivotal role. Even the President of the European Council exercises their

external tasks “without prejudice to the powers conferred on the High Representative of the Union for

Foreign Affairs and Security Policy” (Article 15(6)), albeit “at his [politically higher] level”. The HR is

appointed through qualified majority by the European Council (with the agreement of the Commission

President). He (or she) "implements the common foreign and security policy of the Union" (Article

18(2)), chairs the Foreign Affairs Council, is a de facto member of the European Council (Article 15),

assists the Council and the Commission in achieving a consistent policy (Article 21), together with the

Council, ensures compliance with the policy by the Member States (Article 24, paragraph 3) and is

therefore clearly the pivot around which the entire common foreign, security and defence policy

revolves.

Not only the Commission, but also Parliament has a much more limited role in this policy area. Although

Parliament is consulted by the HR (Article 36), the fact that 'legislative' acts for the CFSP are excluded

(Article 24), seriously limits Parliament's formal role in this area. This is even though Parliament is seen

as one of the most active parliaments worldwide in relation to foreign policy. Concurrently, this leads

to complex situations where (for example because of a joint proposal of the HR and the Commission)

decisions cover both CFSP and other areas. In those cases, the “specific rules and procedures” for the

CFSP (Article 24) necessitate the adoption of different acts with different legal bases in different treaties

and with a very varying role for Parliament.

The exclusion of legislative acts (i.e. the impossibility of adopting directives or regulations in this area)

does not mean that the CFSP decisions are not binding on the Member States. Article 28 TEU states

that these decisions are binding on the Member States in taking positions and in their further action.

Yet, the role of the Court of Justice is limited. Under Article 40, the Court has the power to review

whether the correct legal basis has been chosen for a decision and, in addition, the Court has the power

to review the validity of restrictive measures against natural or legal persons (the well-known sanctions

against persons or entities suspected of terrorism; Article 275 TFEU). The guiding role that the Court

has regarding the development of, for example, the internal market is thus absent here. Over the past

decade, however, the Court has taken its role under Article 19 TEU seriously and aims to provide judicial

review of cases despite their CFSP context.

28

This brief overview of the current institutional structure and the existing decision-mak ing procedures

allows us to take the next step and analyse options to make the EU more effective, especially in the

28

Ramses A Wessel, ‘Legality in EU Common Foreign and Security Policy: The Choice of the Appropriate Legal Basis’ in

Claire Kilpatrick and Joanne Scott (eds), Contemporary Challenges to EU Legality (Oxford University Press 2021);

Christophe Hillion and Ramses A Wessel, ‘“The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”: Three Levels of Judicial Control over the

CFSP’ [2018] Research Handbook on the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy 65.

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 23

field of EU external action.

29

A final, yet fundamental, remark, concerns the fact that the CFSP decision-

making procedures in the Treaties relate to the adoption of formal CFSP decisions by the Council. After

all, Article 31(1) TEU refers to Decisions taken by the Council (and the European Council) and the entire

procedure, including the voting modalities, seems to relate to these formal decisions only. At the same

time, the Official Journal reveals that not so many formal CFSP decisions are adopted and that CFSP is

in fact largely shaped on the basis of other output, including Council minutes, declarations and EU

positions at other international organisations. With regard to the latter type of 'decisions', Article 34

TEU merely provides that "Member States shall coordinate their action in international organisations

and at international conferences" and that they "shall uphold the Union's positions in such forums".

Article 35 TEU adds that "that decisions defining Union positions and actions adopted pursuant to this

Chapter are complied with and implemented". These provisions do not include a decision-making

procedure, nor do they refer back to the default CFSP procedure. Interestingly enough, it is always

assumed that the specific CFSP rules and procedures, including the unanimity rule, apply for all CFSP

output and not just for the formal Decisions mentioned in Article 31 TEU. The Treaty, however, is far

from clear on this, but practice reveals that the unanimity rule is also applied for the adoption of, for

instance, Union positions at international conferences. While from strictly legal (treaty analysis) point

of view questions can be raised as to the applicable decision-making procedure outside the Council,

the present report follows the practice that Member States can also block CFSP output in the form of

Declarations or EU-positions adopted at international conferences. Hence, the suggestions that will be

made will apply across the board.

29

Ramses A Wessel and others, ‘The Future of EU Foreign, Security and Defence Policy: Assessing Legal Options for

Improvement’ [2021] European Law Journal.

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

24 PE 739.139

3. MAKING THE EU MORE EFFECTIVE

3.1. The Conference on the Future of Europe and potential Treaty

changes

There is now a new momentum to change EU Treaties, or to at least make more use of the possibilities

the Treaties offer to make decision-making more effective. Some Member States and EU institutions

are dissatisfied with the functioning of the EU. In particular, the shift from unanimity to QMV is on the

top of the EU’s agenda, including the Czech Council presidency’s agenda,

30

and this shift might either

happen by amending the Treaties or using the so-called passerelle clauses (the clauses that allow for

changes in a decision-making procedure without Treaty change; see further below). Indeed, one of the

conclusions from the CoFE, at least for some Member States and the EP, is that the EU Treaties should

be amended to make the EU more effective, including in its foreign policy actions. Thus, the outcome

of the CoFE can be seen as a catalyst to potentially change EU Treaties that merits further analysis.

On 10 March 2021, EP President David Sassoli, Portuguese PM António Costa, on behalf of the Council,

and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen signed a joint declaration on the CoFE. In

this joint declaration, they expressed their desire to “show that [the EU] can provide answers to citizens’

concerns and ambitions” and to create an opportunity for a “citizens-focused, bottom-up exercise for

Europeans to have their say on what they expect from the [EU]”.

31

Already however, in March 2021

some Member States excluded the possibility to change the Treaties in response to the outcome of the

CoFE. The non-paper released by 12 Member States

32

emphasised that the “Union framework offers

potential to allow priorities to be addressed in an effective manner” and argued that the CoFE does not

fall within the scope of Article 48 TEU.

33

On 9 May 2021, an inaugural event of the Conference took place in Parliament. A pproximately 800

randomly selected citizens were involved in deliberative sessions. The CoFE concluded on 9 May 2022

and its final report now includes 49 proposals and 326 individual measures to the three EU institutions.

These proposals covered nine broad themes, including a stronger economy, social justice and jobs;

education, culture, youth and sport; digital transformation; European democracy; values and rights,

rule of law, security; climate change, environment; health; EU in the world; and migration.

34

These proposals may require new legislative proposals or even Treaty amendments in certain cases. An

EU Law Professor and his team categorised the proposals into four categories and concluded that 23

30

The current trio is made up of the presidencies of France (1 January to 30 June 2022), the Czech Republic (1 July - 31

December 2022) and Sweden (1 January 2023 to 30 June 2023).

31

David Sassoli, António Costa and Ursula von der Leyen, ‘Joint Declaration on the Conference on the Future of Europe:

Engaging with Citizens for Democracy - Building a More Resilient Europe’

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/en_-_joint_declaration_on_the_conference_on_the_future_of_europe.pdf

.

32

Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Slovakia and

Sweden

33

Dutch Permanent Representation, ‘Non-Paper on the Conference on the Future of Europe’ (24 March 2021)

https://www.permanentrepresentations.nl/documents/publications/2021/03/24/non-paper-on-the-conference-on-the-

future-of-europe accessed 30 September 2022.

34

EU, ‘Conference on the Future of Europe - Report on the Final Outcome’ 5 https://prod-cofe-platform.s3.eu-central-

1.amazonaws.com/8pl7jfzc6ae3jy2doji28fni27a3.

The implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the use of Qualified Majority Voting

PE 739.139 25

proposals need no new action; 21 need new action by Member States; 113 require new action by the

EU; and only 21 require Treaty change. The latter includes new competences in welfare (7), education

(5), institutional reforms (4), health care (2), taxation (2) and energy (1). Thus, the percentage of

proposals requiring Treaty change is approximately 12 percent.

35

After the closing conference of the CoFE, two competing visions appeared on whether EU Treaties

should be modified. On the one hand, a non-paper was released by thirteen Member States

36

that

underlined that “Treaty change has never been a purpose of the Conference [on the future of Europe].

What matters is that we address the citizens’ ideas and concerns. While we do not exclude any options

at this stage, we do not support unconsidered and premature attempts to launch a process towards

Treaty change”. This non-paper also emphasised the potential to rely on underused Treaty provisions

for more effective EU level solutions. On the other hand, six other Member States (and informally

France)

37

also released a non-paper on the same matter but approached the outcome of the CoFE more

differentiated. These six countries did not rule out the potential change of the Treaties. In fact, in their

letter, they called on the Commission to differentiate between proposals already being implemented;

proposals that could be quickly implemented within the existing Treaty framework; and proposals that

would require Treaty change.

38

Meanwhile, Parliament was also quick to react to the outcome on the CoFE. On 9 June 2022, Parliament,

for the first time in its history, adopted a resolution – with 355 votes in favour, 154 against, and 48

abstentions – calling for a Convention for the revision of the Treaties. Given that the proposals of the

Conference require amendments of the Treaties, it also called on the AFCO committee to prepare

proposals for Treaty amendments accordingly. The resolution foresees the amendment of the Treaties

to make sure the Union has the competence to take more effective action during future crises. The

resolution, among others, calls for reforming voting procedures in the Council to enhance the EU’s

capacity to act, including switching from unanimity to QMV, in areas such as sanctions, the so-called

passerelle clause, and in emergencies.

39

In particular, the EP resolution proposes the following Treaty articles to be amended as follows:

40

On the adoption of restrictive measures (sanctions):

— Article 29 TEU "The Council shall adopt decisions which shall define the approach of the Union

to a particular matter of a geographical or thematic nature. Where a decision provides for the

interruption or reduction, in part or completely, of economic and financial relations with one or

35

Alemanno Alberto, ‘Conference on the Future of Europe’ (Twitter, 2022)

https://twitter.com/alemannoEU/status/1509819879410515970

accessed 22 September 2022.

36

Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and

Sweden

37

Germany, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Spain. France would have been part of this group but given

that at the time of publishing the non-paper France held the EU Council presidency, it did not sign the letter

38

Alemanno Alberto, ‘13 Member States opposing Treaty reform?’ (Twitter, 2022)

https://twitter.com/alemannoEU/status/1526922932970262528

accessed 21 October 2022.

39

European Parliament, ‘Parliament Activates Process to Change EU Treaties’ (9 June 2022)

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220603IPR32122/parliament-activates-process-to-change-eu-

treaties accessed 21 October 2022.

40

The AFCO has started to prepare a new draft report AFCO/9/09208, 2022/2051(INL) “Proposals of the European

Parliament for the amendment of the Treaties” (pursuant to article 48 of the Treaty on the European Union and Rule 85

of Parliament’s Rules of Procedure)

IPOL | Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs

26 PE 739.139

more third countries, the Council shall act by a qualified majority. Member States shall ensure that

their national policies conform to the Union positions."

On the competence of the European Council to change a unanimity-requirement into QMV:

— Article 48(7), fourth subparagraph TEU "For the adoption of these decisions, the European

Council shall act by a qualified majority as defined in Article 238(3), point (b), of the [TFEU] after

obtaining the consent of the European Parliament, which shall be given by a majority of its component

members."

41

While the proposed changes are understandable in the context of the current debate, one may wonder

whether Article 29 TEU is the best provision to be changed in this context. Article 29 TEU does not deal

with voting rules but lays down a general competence to adopt decisions alongside an indication of

the binding force of those decisions. CFSP voting rules are laid down in Article 31 TEU. The proposed

change could be in that particular provision, which already included other exceptions to the unanimity

rule. Thus, a modified Article 31(2) TEU could include an addition exception to the unanimity rule:

"By derogation from the provisions of paragraph 1, the Council shall act by qualified majority:

[…]

– Where a decision provides for the interruption or reduction, in part or completely, of economic and

financial relations with one or more third countries."

The Commission also adopted a Communication setting out how it can follow up on the outcome of

the CoFE. Seemingly, it adopted a differentiated approach, similar to the six Member States mentioned

above, in that the Commission set out four categories of responses. These were; (a) where the

Commission is already implementing initiatives; (b) where proposals have been made by the

Commission and the co-legislators are currently working; (c) where the Commission is already planning

to make proposals; and (d) where proposals made by the Conference are partly or wholly new and