A Framework for Managing

Fraud Risks in Federal Programs

July 2015 GAO-15-593SP

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

Evaluate outcomes using a

risk-based approach and

adapt activities to improve

fraud risk management.

Conduct risk-based monitoring

and evaluation of fraud risk

management activities with a

focus on outcome measurement.

Collect and analyze data from

reporting mechanisms and instances

of detected fraud for real-time

monitoring of fraud trends.

Use the results of monitoring, evaluations,

and investigations to improve fraud

prevention, detection, and response.

Design and implement a strategy

with specific control activities

to mitigate assessed fraud risks

and collaborate to help ensure

effective implementation.

Develop, document, and

communicate an antifraud strategy,

focusing on preventive control

activities.

Consider the benefits and costs of

controls to prevent and detect

potential fraud, and develop a

fraud response plan.

Establish collaborative

relationships with stakeholders

and create incentives to help

ensure effective implementation

of the antifraud strategy.

Commit to combating fraud by creating

an organizational culture and structure

conducive to fraud risk management.

Demonstrate a senior-level commitment

to combat fraud and involve all

levels of the program in setting

an antifraud tone.

Designate an entity within the

program office to lead fraud

risk management activities.

Ensure the entity has

defined responsibilities and

the necessary authority to

serve its role.

Plan regular fraud risk

assessments and assess risks

to determine a fraud risk profile.

Tailor the fraud risk assessment

to the program, and involve

relevant stakeholders.

Assess the likelihood and impact

of fraud risks and determine risk

tolerance.

Examine the suitability of existing

controls, prioritize residual risks,

and document a fraud risk profile.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

M

O

N

I

T

O

R

I

N

G

A

N

D

F

E

E

D

B

A

C

K

M

O

N

I

T

O

R

I

N

G

A

N

D

F

E

E

D

B

A

C

K

Prevention

DetectionResponse

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

E

A

N

D

A

D

A

P

T

D

E

S

I

G

N

A

N

D

I

M

P

L

E

M

E

N

T

C

O

M

M

I

T

A

S

S

E

S

S

A Framework for Managing

Fraud Risks in Federal Programs

July 2015

Highlights of GAO-15-593SP, a

Framework for Managing Fraud Risks

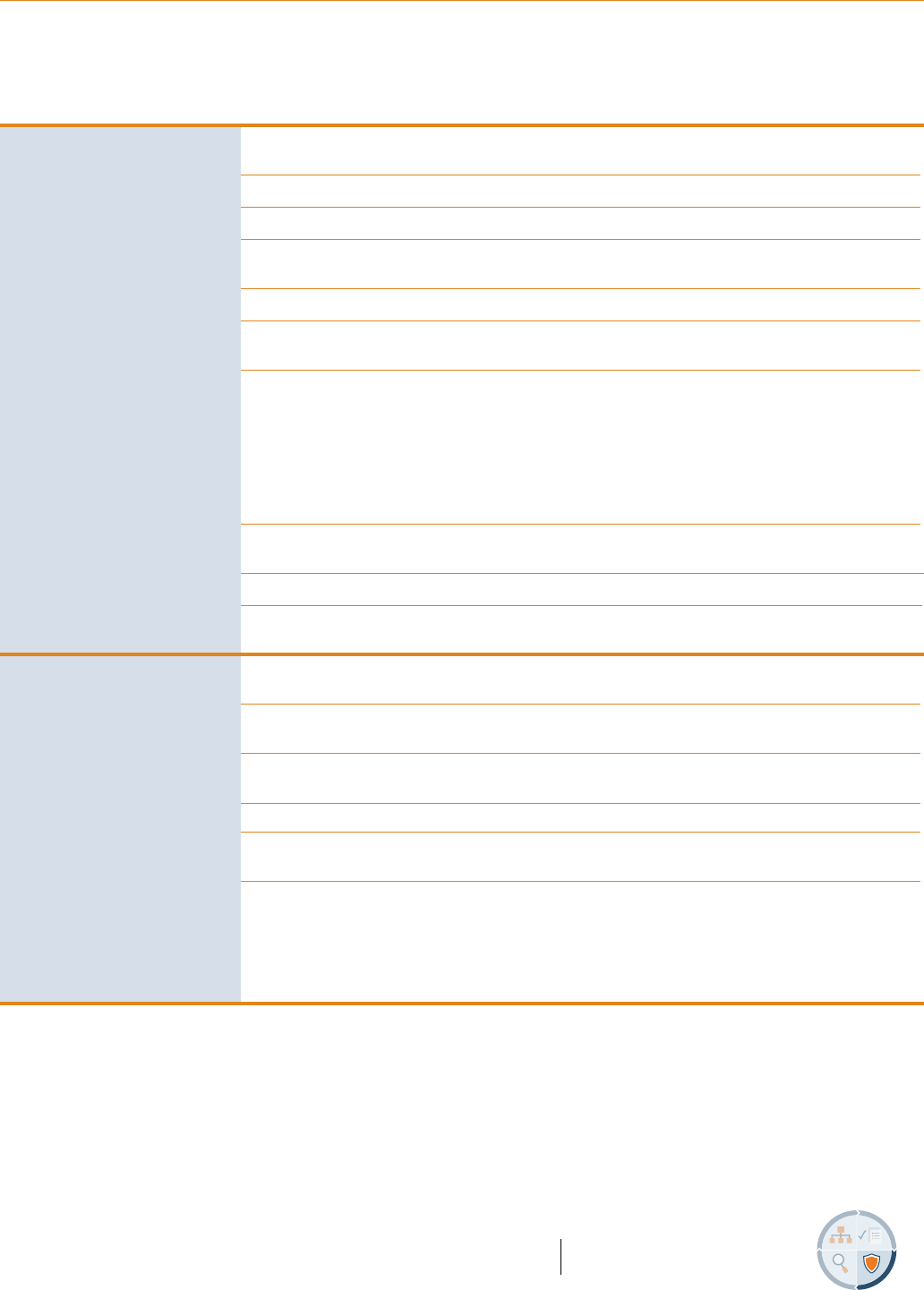

The Fraud Risk Management Framework and Selected Leading Practices

To help managers combat fraud and

preserve integrity in government

agencies and programs, GAO identified

leading practices for managing fraud

risks and organized them into a

conceptual framework called the

Fraud Risk Management Framework

(the Framework). The Framework

encompasses control activities to

prevent, detect, and respond to fraud,

with an emphasis on prevention, as well

as structures and environmental factors

that influence or help managers achieve

their objective to mitigate fraud risks.

In addition, the Framework highlights

the importance of monitoring and

incorporating feedback, which are

ongoing practices that apply to all four

of the components described below.

What GAO Found Why GAO Did This Study

Fraud poses a significant risk to the integrity of federal programs and erodes public trust

in government. Managers of federal programs maintain the primary responsibility for

enhancing program integrity. Legislation, guidance by the Office of Management and

Budget (OMB), and new internal control standards have increasingly focused on the

need for program managers to take a strategic approach to managing improper payments

and risks, including fraud. Moreover, GAO’s prior reviews highlight opportunities for

federal managers to take a more strategic, risk-based approach to managing fraud risks

and developing effective antifraud controls. Proactive fraud risk management is meant

to facilitate a program’s mission and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer dollars and

government services serve their intended purposes.

The objective of this study is to identify leading practices and to conceptualize these practices

into a risk-based framework to aid program managers in managing fraud risks. To address this

objective, GAO conducted three focus groups consisting of antifraud professionals. In addition,

GAO interviewed federal Offices of Inspector General (OIG), national audit institutions

from other countries, the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development, as well as antifraud experts representing private companies, state and local audit

associations, and nonprofit entities. GAO also conducted an extensive literature review and

obtained independent validation of leading practices from program officials.

View GAO-15-593SP. For more information, contact Steve Lord at (202) 512-6722 or [email protected].

i

Contents

Foreword 1

Introduction 2

A Framework for Eective Fraud Risk Management 5

1. Commit to Combating Fraud by Creating an Organizational Culture and Structure

Conducive to Fraud Risk Management 8

1.1 Create an Organizational Culture to Combat Fraud at All Levels of the Agency 9

1.2 Create a Structure with a Dedicated Entity to Lead Fraud Risk Management

Activities 10

2. Plan Regular Fraud Risk Assessments and Assess Risks to Determine a Fraud

Risk Prole 11

2.1 Plan Regular Fraud Risk Assessments That Are Tailored to the Program 12

2.2 Identify and Assess Risks to Determine the Program’s Fraud Risk Prole 12

3. Design and Implement a Strategy with Specic Control Activities to Mitigate

Assessed Fraud Risks and Collaborate to Help Ensure Eective Implementation 17

3.1 Determine Risk Responses and Document an Antifraud Strategy Based on the

Fraud Risk Prole 18

3.2 Design and Implement Specic Control Activities to Prevent and Detect Fraud 20

3.3 Develop a Plan Outlining How the Program Will Respond to Identied Instances

of Fraud 25

3.4 Establish Collaborative Relationships with Stakeholders and Create Incentives to Help

Ensure Eective Implementation of the Antifraud Strategy 25

4. Evaluate Outcomes Using a Risk-Based Approach and Adapt Activities to Improve

Fraud Risk Management 28

4.1 Conduct Risk-Based Monitoring and Evaluate All Components of the Fraud Risk

Management Framework 29

4.2 Monitor and Evaluate Fraud Risk Management Activities with a Focus on Measuring

Outcomes 30

4.3 Adapt Fraud Risk Management Activities and Communicate the Results of Monitoring

and Evaluations 31

Appendix I: Objective, Scope, and Methodology 33

Appendix II: Challenges Related to Measuring Fraud 36

Appendix III: Examples of Control Activities and Additional Information on Leading

Practices for Data Analytics and Fraud-Awareness Initiatives 37

Appendix IV: Risk Factors for Assessing Improper-Payment Risk 44

Appendix V: Example of a Fraud Risk Prole 45

Appendix VI: Endnotes 47

Appendix VII: GAO Contact and Sta Acknowledgments 55

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs

GAO-15-593SP

ii

Abbreviations

ACFE AssociationofCertiedFraudExaminers

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

COSO Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission

CPI Center for Program Integrity

DOE Department of Energy

ERM enterprise risk management

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

FPS Fraud Prevention System

Framework GAO’s Fraud Risk Management Framework

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

IPERA Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Act of 2010

IPERIA Improper Payments Elimination and Recovery Improvement Act of 2012

IPIA Improper Payments Information Act of 2002

IRS Internal Revenue Service

LIHEAP Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OIG OfceofInspectorGeneral

OMB OfceofManagementandBudget

SSA Social Security Administration

SSN Social Security number

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States.

The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission

from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission

from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Tables

Table 1: Leading Practices for Creating a Culture and Structure to Manage Fraud Risks 8

Table 2: Leading Practices for Planning and Conducting Fraud Risk Assessments 11

Table 3: Leading Practices for Designing and Implementing an Antifraud Strategy

with Control Activities 17

Table 4: Key Elements of an Antifraud Strategy 19

Table 5: Additional Leading Practices for Data-Analytics Activities, Fraud-Awareness

Initiatives, Reporting Mechanisms, and Employee-Integrity Activities 23

Table 6: Leading Practices for Monitoring, Evaluating, and Adapting Fraud Risk

Management Activities 28

Table 7: Leading Practices for Developing and Conveying Training Content 43

Table 8: Elements of a Fraud Risk Prole for One Hypothetical Fraud Risk 45

Figures

Figure 1: Interdependent and Mutually Reinforcing Categories of Fraud Control Activities 5

Figure 2: The Fraud Risk Management Framework 6

Figure 3: Example of Two-Dimensional Risk Matrices 14

Figure 4: Key Elements of the Fraud Risk Assessment Process 16

Figure 5: Potential Responses to Fraud Risks Based on Assessed Likelihood, Impact, and

Risk Tolerance 18

Figure 6: Incorporating Feedback to Continually Adapt Fraud Risk Management Activities 32

Figure 7: Examples of Controls and Activities to Prevent, Detect, and Respond to Fraud 38

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

1

Foreword

I am pleased to present GAO’s Fraud Risk Management Framework (the Framework). The Framework includes a

comprehensive set of leading practices that serve as a guide for program managers to use when developing or enhancing

efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based manner. As the steward of taxpayer dollars, federal managers have

the ultimate responsibility in overseeing how hundreds of billions of dollars are spent annually. Thus, they are well

positioned to use these practices, while considering the related fraud risks as well as the associated benefits and costs of

implementing the practices, to help ensure that taxpayer resources are spent efficiently and effectively.

The revised Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government requires managers to assess fraud risks as part

of their internal control activities. These standards become effective at the start of fiscal year 2016. The Framework

provides comprehensive guidance for conducting these assessments and using the results as part of the development of a

robust antifraud strategy. It also describes leading practices for establishing an organizational structure and culture that

are conducive to fraud risk management, designing and implementing controls to prevent and detect potential fraud,

and monitoring and evaluating to provide assurances to managers that they are effectively preventing, detecting, and

responding to potential fraud.

The Framework has gone through a deliberative process, and a wide range of views were solicited in developing leading

practices and ensuring their applicability to the federal government. This process included interactions with selected

federal agency program officials, Offices of Inspector General, the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development, as well as antifraud experts from state and local governments, private companies, other

national audit institutions, and nongovernmental organizations. The views of all parties were thoroughly considered

in finalizing this document. I extend special thanks to those who commented and suggested improvements to the

Framework.

Stephen M. Lord

Managing Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

U.S. Government Accountability Office

July 2015

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

2

Effective fraud risk management helps to ensure that federal

programs’ services fulfill their intended purpose, funds are

spent effectively, and assets are safeguarded.

1

Legislation

and guidance issued since 2002 has focused managers’

attention on addressing improper payments, which

includes payments made as a result of fraud.

2

However, the

deceptive nature of fraud makes it difficult to measure in a

reliable way, and federal managers face fraud risks beyond

those captured by improper payments, such as risks that do

not pose a direct financial cost to taxpayers. For example,

passport fraud poses a risk, because fraudulently-obtained

passports can be used to conceal the true identity of the user

and potentially facilitate other crimes, such as international

terrorism and drug trafficking.

3

Managers of government programs maintain the primary

responsibility for enhancing program integrity; however,

the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) plays a key

role in issuing guidance to assist managers with combating

government-wide fraud, waste, and abuse. OMB has

established guidance for federal agencies on reporting,

reducing, and recovering improper payments, including

Appendix C to Circular A-123.

4

Moreover, legislation

and guidance has increasingly focused on the need for

program managers to take a strategic approach to managing

risks, including fraud. For example, in 2014, OMB

recommended that agencies consider adopting enterprise-

wide risk management, an approach for addressing the full

spectrum of risks and challenges related to achieving the

agencies’ missions.

5

Our body of work has shown that managers have taken

positive steps to address improper payments, but work

remains to improve the integrity of government programs.

6

In particular, our work has shown that opportunities exist

for federal managers to take a more strategic, risk-based

approach to managing fraud risks and developing effective

antifraud controls. For example, we reported in November

2014 on fraud related to disability benefit claims,

concluding that the agency responsible for the program

launched initiatives to combat fraud, but lack of planning,

data, and coordination hampered the success of its efforts.

7

We also found in December 2014 that, to comply with

legislation on improper payments, one agency developed a

process to assess improper-payment risks, but its 2011 risk

assessments did not fully evaluate risks and the agency did

not always include a clear basis for risk determinations.

8

In addition, our reports on high-risk areas in the federal

government have consistently highlighted programs’ efforts

to manage fraud, waste, and abuse.

9

To focus managers’

attention on the need to take a more strategic, risk-based

approach to managing fraud risks, the Standards for Internal

Control in the Federal Government, commonly known

as the Green Book, and hereafter referred to as Federal

Internal Control Standards, requires managers to consider

the potential for fraud when identifying, analyzing, and

responding to risks.

10

Implementing a risk-based approach to addressing

potential fraud in the federal government poses a unique

set of challenges to federal managers, given their programs’

Introduction

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Fraudposesasignicantrisktotheintegrityoffederal

programs and erodes public trust in government.

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

3

mission to provide the public with a broad range of critical,

often time-sensitive, services and financial assistance.

Managers may perceive a conflict between their priorities

to fulfill the program’s mission, such as efficiently

disbursing funds or providing services to beneficiaries, and

taking actions to safeguard taxpayer dollars from improper

use. However, the purpose of proactively managing fraud

risks is to facilitate, not hinder, the program’s mission

and strategic goals by ensuring that taxpayer dollars and

government services serve their intended purposes.

The objective of this study is to identify concepts and

leading practices to aid federal program managers in

managing fraud risks. We organized these concepts and

practices into a Fraud Risk Management Framework

(the Framework). The leading practices described in the

Framework are meant to provide additional guidance

for implementing requirements contained in Federal

Internal Control Standards, improper-payment legislation,

and OMB circulars.

11

In developing the Framework, we

considered the fact that fraud can take many forms across

the federal government, some programs are more vulnerable

to fraud than others, and expertise to combat fraud varies

within programs. Managers are responsible for determining

the extent to which the leading practices presented in the

Framework are relevant to their program and for tailoring

the practices, as appropriate, to align with the program’s

operations. In doing so, managers consider applicable laws

and regulations, the specific risks the program faces, and

the associated benefits and costs of implementing each

practice. While the primary target audience of this study

is managers in the U.S. federal government, the practices

and concepts described in the Framework may also be

applicable to state, local, and foreign government agencies,

as well as nonprofit entities that are responsible for fraud

risk management.

To address our objective, we gathered testimonial evidence

from multiple sources, including officials from Offices of

Inspector General (OIG) for eight U.S. federal agencies,

the Council of the Inspectors General for Integrity and

Efficiency, and the national audit offices of three other

countries.

12

Specifically, we interviewed officials from the

OIGs of the five largest federal agencies by outlays and the

five largest grant-making agencies, as well as officials from

three national audit offices that have published reports

related to our objective.

13

In addition, we interviewed

antifraud experts from 10 other external entities, which we

identified through our background research and discussions

with internal fraud experts. We selected entities that

represent different sectors, including private companies,

state and local audit associations, nonprofit organizations,

and intergovernmental organizations. The entities we

selected also had expertise in different areas related to fraud

risk management, such as audits, investigations, trainings,

the design and implementation of fraud controls, and

developing integrity frameworks.

Further, we attended a prominent antifraud conference

and conducted three focus groups of 7 to 10 fraud risk

management experts during the conference. Two focus

groups consisted of fraud risk management experts that

presented at the conference, and one focus group involved

conference participants with relevant antifraud experience

or knowledge. We also conducted an extensive literature

review, a review of GAO’s past work on fraud, internal

controls, and program integrity, as well as additional

reading that was recommended in our interviews and by

internal experts. As part of our research, we considered

existing frameworks and guides related to fraud risk

management and integrity, including publications by

the Australian National Audit Office, the Committee of

Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission

(COSO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD), as well as the Institute of

Internal Auditors, American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants, and Association of Certified Fraud Examiners

(ACFE), among others.

14

Introduction

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

4

To validate our leading practices, we asked program officials

associated with the same agency as the OIGs we interviewed

to review the leading practices in a draft of the Framework.

Moreover, to gain an additional perspective of a smaller

agency than those we selected above, we asked a program

within an agency with one of the lowest amount of outlays

for fiscal year 2013 to review the leading practices. We

incorporated input we received from programs into our

study, as appropriate. In addition to the comments we

sought for independent validation of leading practices, we

provided a draft of the Framework to selected officials and

experts who participated in our interviews to confirm that we

captured their comments accurately and completely (see app.

I for a detailed discussion of our methodology).

We conducted our work from March 2014 to July 2015 in

accordance with all sections of GAO’s Quality Assurance

Framework that are relevant to our objective. This

framework requires that we plan and perform our work

to obtain sufficient and appropriate evidence to meet our

stated objective and to discuss any limitations in our work.

We believe that the information and data obtained, and

the analysis conducted, provide a reasonable basis for any

conclusions in this product.

Introduction

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

5

A Framework for Effective Fraud Risk Management

The objective of fraud risk management is to ensure program

integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating the

likelihood and impact of fraud.

15

As indicated above, this

objective is meant to facilitate achievement of the program’s

broader mission and strategic goals by helping to ensure

that funds are spent effectively, services fulfill their intended

purpose, and assets are safeguarded.

16

The critical control

activities for managing fraud risks fall into three general

categories—prevention, detection, and response. These

categories are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. For

instance, detection activities, like surprise audits, also serve

as deterrents because they create the perception of controls

and possibility of punishment to discourage fraudulent

behavior. In addition, response efforts can inform preventive

activities, such as using the results of investigations to

enhance applicant screenings and fraud indicators.

As depicted by the larger circle for prevention in figure 1,

preventive activities generally offer the most cost-efficient

use of resources, since they enable managers to avoid a costly

and inefficient “pay-and-chase” model.

17

Therefore, leading

practices for strategically managing fraud risks emphasize

risk-based preventive activities, as discussed further in

subsequent sections.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Figure 1: Interdependent and Mutually Reinforcing Categories of Fraud Control Activities

DetectionResponse

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

Prevention

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

6

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Design and implement a

strategy with specific control

activities to mitigate assessed

fraud risks and collaborate

to help ensure effective

implementation.

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

Commit to combating fraud by

creating an organizational culture

and structure conducive to

fraud risk management.

Plan regular fraud risk

assessments and assess risks to

determine a fraud risk profile.

Evaluate outcomes using a

risk-based approach and adapt

activities to improve fraud

risk management.

M

O

N

I

T

O

R

I

N

G

A

N

D

F

E

E

D

B

A

C

K

M

O

N

I

T

O

R

I

N

G

A

N

D

F

E

E

D

B

A

C

K

Prevention

DetectionResponse

E

V

A

L

U

A

T

E

A

N

D

A

D

A

P

T

D

E

S

I

G

N

A

N

D

I

M

P

L

E

M

E

N

T

C

O

M

M

I

T

A

S

S

E

S

S

The Framework encompasses the control activities described

above, as well as structures and environmental factors that

influence or help managers achieve their objective to mitigate

fraud risks.

18

The Framework consists of the following four

components for effectively managing fraud risks:

1. Commit—Commit to combating fraud by creating an

organizational culture and structure conducive to fraud

risk management.

2. Assess—Plan regular fraud risk assessments and assess

risks to determine a fraud risk profile.

3. Design and Implement—Design and implement a

strategy with specific control activities to mitigate assessed

fraud risks and collaborate to help ensure effective

implementation.

4. Evaluate and Adapt—Evaluate outcomes using a risk-

based approach and adapt activities to improve fraud risk

management.

In addition, the Framework reflects activities related to monitoring

and feedback mechanisms, which include ongoing practices that

apply to all four concepts above, as depicted in figure 2.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Framework Overview

Figure 2: The Fraud Risk Management Framework

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

7

The “environment,” as shown by the outer circle in figure

2, refers to contextual factors and stakeholders, either

internal or external to an agency or program, which

influence fraud risk management activities. For instance,

an agency may have other initiatives to manage risks, such

as enterprise-wide risk management efforts. Fraud risk

management activities may be incorporated into or aligned

with such internal activities and strategic objectives, to the

extent they exist. Budgetary conditions can also affect a

program’s ability to pursue certain types of resource-

intensive activities. In addition, activities of internal

stakeholders, such as an OIG and its capacity to investigate

potential fraud, can also influence and inform certain fraud

risk management activities within a program.

19

Other stakeholders and factors are external to a program

and may also be beyond managers’ direct control. These

include other entities, such as contractors, different

federal agencies, or state and local governments, as well as

relevant laws, guidance, and standards, as described above,

which may also affect managers’ ability to implement

specific activities.

20

For instance, participants of a forum

we hosted in January 2013 about data analytics discussed

legal constraints they said can hinder agencies’ ability

to use data to detect fraud, such as steps the Computer

Matching Act requires of agencies before they can use data

for matching purposes.

21

Asaresultofcontextualdifferencesbetweenprograms,theapproachmanagersusetoimplementthe

leadingpracticesdescribedintheFrameworkmayalsovary.Forexample,someprogramsmayalready

havecertaincontrolactivitiesinplaceaspartofexistingriskmanagementefforts.Theleadingpracticesin

theFrameworkcanbemodiedtotthecircumstancesandconditionsthatarerelevanttoeachprogram.

Moreover, the practices in the Framework are not necessarily meant to be sequential or interpreted as a

step-by-step process, unless indicated otherwise.

All subheaders (e.g., 1.1 and 1.2) in the sections below refer to overarching concepts of fraud risk

management. Below each subheader we discuss leading practices that demonstrate ways for program

managers to carry out the overarching concepts of the Framework. The overarching concepts and leading

practices are summarized in a table at the beginning of each section, as follows:

Any use of the term “should” or “requires” denotes a standard or requirement described in improper-

payment legislation, OMB guidance, or principles in Federal Internal Control Standards. We use terms

like “may” or “should consider” when referring to attributes in Federal Internal Control Standards, which

arecharacteristicsthatexplainprinciplesinfurtherdetail,butarenotrequirementsformanagers.Tothe

extenttheyarerelevant,wereferencethesesourcesintheendnotes(seeapp.VI);linkstorelevantlaws,

guidance,andstandardsmaynotbeexhaustive.

Overarching Concepts

Leading Practices

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Framework Overview

A Guide for Reading the Framework

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

8

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Commit to Combating Fraud by Creating an Organizational Culture and Structure

Conducive to Fraud Risk Management

Table 1: Leading Practices for Creating a Culture and Structure to Manage Fraud Risks

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

1.1 Create an Organizational Culture to Combat Fraud at All Levels of the Agency

Demonstrate a senior-level commitment to integrity and combating fraud.

Involve all levels of the agency in setting an antifraud tone that permeates the organizational culture.

1.2 Create a Structure with a Dedicated Entity to Lead Fraud Risk Management Activities

Designate an entity to design and oversee fraud risk management activities that

• understands the program and its operations, as well as the fraud risks and controls throughout the

program;

a

• hasdenedresponsibilitiesandthenecessaryauthorityacrosstheprogram;

• hasadirectreportinglinetosenior-levelmanagerswithintheagency;and

• islocatedwithintheagencyandnottheOfceofInspectorGeneral(OIG),sothelattercanretainits

independence to serve its oversight role.

In carrying out its role, the antifraud entity, among other things

• servesastherepositoryofknowledgeonfraudrisksandcontrols;

• managesthefraudrisk-assessmentprocess;

• leadsorassistswithtrainingsandotherfraud-awarenessactivities;and

• coordinates antifraud initiatives across the program.

1

a

Forthesakeofconsistency,wegenerallyrefertoprogramsthroughoutthisstudy;however,thepracticeswediscusscanapplytoagenciesaswell.Managersdecide

whether to carry out each aspect of fraud risk management at the program level or agency level.

Commit

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

9

1.1 Create an Organizational Culture to

Combat Fraud at All Levels of the Agency

Managers who effectively manage fraud risks demonstrate

a senior-level commitment to integrity and combating

fraud.

22

Various actions can help managers meet this leading

practice. For instance, according to experts we interviewed

and literature we reviewed, managers can demonstrate their

commitment to combating fraud and promoting integrity

by conducting self-assessments of their performance in

managing fraud risks, or establishing a code of conduct that

sets expectations for ethical behavior, integrity standards

for new hires, and an attitude statement towards fraud.

Moreover, as discussed in detail below, managers who

effectively manage fraud risks develop, document, and

communicate an antifraud strategy that describes the

program’s approach to combating fraud. Effective fraud

risk managers also involve all levels of the agency, such as

mid-level managers and entry-level employees, in setting an

antifraud tone that permeates the organizational culture.

According to officials of one agency we interviewed, there

needs to be “horizontal pressure” among peers within an

agency to encourage fraud risk management, not just “vertical

pressure.” The text box below provides an example of an

agency that has demonstrated senior-level commitment and

established a dedicated antifraud entity to combat fraud,

waste, and abuse, as discussed in the next section.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Commit

GAO’s High-Risk Series and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

a

Every 2 years at the start of a new Congress, GAO calls attention to agencies and program areas that are high risk due to their vulnerabilities to fraud,

waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or are most in need of transformation. We designated Medicare as a high-risk program in 1990 due to its size,

complexity,andsusceptibilitytomismanagementandimproperpayments.CMS,whichadministersMedicareforHHS,isresponsibleforoverseeingthe

program and safeguarding it from loss.

b

The other criteria include capacity, an action plan, monitoring, and demonstrated progress. See www.gao.gov for additional information on our high-risk

series.

c

GAO, High-Risk Series: An Update, GAO-15-290 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 11, 2015).

Weusevecriteriawhenreviewingstepstakeninhigh-riskareas,

a

one of which is “leadership

commitment.”

b

CMS has met our criterion for demonstrating strong commitment to—and top leadership

support for—reducing the incidence of improper payments in the Medicare program. The Department

of Health and Human Services (HHS) has continued to designate “strengthened program integrity

throughimproperpaymentreductionandghtingfraud”asadepartmentstrategicpriority.Throughits

dedicated Center for Program Integrity, which is CMS’s focal point for all national Medicare program-

integrity issues, CMS has taken multiple actions to improve in this area. For instance, CMS centralized

the development and implementation of automated edits—prepayment controls used to deny Medicare

claims that should not be paid. We reported in February 2015 that while CMS has met the criterion for

leadership commitment, and has partially met each of the other criteria for removing Medicare improper

payments from the High-Risk List, additional actions are needed to address fraud, waste, and abuse.

c

For instance, we reported that CMS could address the identity theft risks associated with having Social

SecuritynumbersonMedicarebeneciaries’health-insurancecards.Havingsenior-levelcommitmentand

adedicatedantifraudentity,asexempliedbyCMS,arefundamentalaspectsoftheFramework.However,

other components and leading practices discussed in subsequent sections are also critical for effectively

managing fraud risks.

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

10

1.2 Create a Structure with a Dedicated

Entity to Lead Fraud Risk Management

Activities

Federal Internal Control Standards requires managers to

establish an organizational structure, among other actions,

to achieve the program’s objectives.

23

A leading practice for

managing fraud risks is to designate an entity within that

structure to design and oversee fraud risk management

activities.

24

The dedicated entity could be an individual

or a team, depending on the needs of the agency. For

purposes of this study, we refer to this individual or team

as the “antifraud entity.” In addition to the antifraud entity,

employees across an agency or program, as well as external

entities, can be responsible for the actual implementation of

fraud controls. Moreover, Federal Internal Control Standards

requires managers to hold employees and external entities

accountable for their internal control duties, which include

activities for managing fraud risks.

25

We identified the following leading practices to help

managers decide who to assign as the antifraud entity. The

antifraud entity

• understands the program and its operations, as well as the

fraud risks and controls throughout the program;

• has defined responsibilities and the necessary authority

across the program; and

• has a direct reporting line to senior-level managers within

the agency.

In addition, it is critical that the antifraud entity be located

within the agency and not the OIG, so the OIG can retain

independence to serve its oversight role.

26

The specific

department or unit that serves as the antifraud entity may

vary, depending on factors like the existing structure or

expertise within an agency. For instance, officials of one

agency said the Office of General Counsel is best-suited to

serve as the antifraud entity, given the agency’s particular

set of circumstances. Among other reasons, officials noted

having the Office of General Counsel as the lead on

combating fraud helps to alleviate perceived conflicts of

interest that program managers may have between serving

the agency’s mission and managing fraud risks. In addition,

agencies may have existing departments that are responsible

for enterprise-wide risk management or managing risks

related to improper payments. These departments may

have functions that overlap with fraud risk management

activities and they may be able to incorporate the roles

and responsibilities of the antifraud entity. While the

placement of an antifraud entity can vary by agency, the

leading practices noted above for assigning the entity can

aid managers in making this determination in any context.

As noted, the antifraud entity designs and oversees fraud risk

management activities. Additional leading practices related to

the antifraud entity’s responsibilities include the following:

• serves as the repository of knowledge on fraud risks and

controls,

• manages the fraud risk assessment process, and

• leads or assists with trainings and other fraud-awareness

activities.

Other responsibilities may vary by program; however,

the entity is generally responsible for coordinating

antifraud initiatives across the program, such as facilitating

communication with management and among stakeholders

on fraud-related issues.

27

For instance, the Center for

Program Integrity at CMS, the antifraud entity noted in

the text box above, was designed to oversee all of CMS

interactions and coordinate with key stakeholders related

to program integrity (e.g., the Department of Justice, the

OIG, and state law-enforcement agencies) for purposes of

combating fraud and abuse.

28

Commit

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

11

Assess

Plan Regular Fraud Risk Assessments and Assess Risks to Determine a Fraud

RiskProle

2.1 Plan Regular Fraud Risk Assessments That Are Tailored to the Program

Tailor the fraud risk assessment to the program.

Plan to conduct fraud risk assessments at regular intervals and when there are changes to the program or

operating environment, as assessing fraud risks is an iterative process.

Identifyspecictools,methods,andsourcesforgatheringinformationaboutfraudrisks,includingdataon

fraud schemes and trends from monitoring and detection activities.

Involve relevant stakeholders in the assessment process, including individuals responsible for the design

and implementation of fraud controls.

2.2 Identify and Assess Risks to Determine the Program’s Fraud Risk Prole

Identify inherent fraud risks affecting the program.

Assess the likelihood and impact of inherent fraud risks.

• Involvequaliedspecialists,suchasstatisticiansandsubject-matterexperts,tocontributeexpertiseand

guidance when employing techniques like analyzing statistically valid samples to estimate fraud losses

and frequency.

• Considerthenonnancialimpactoffraudrisks,includingimpactonreputationandcompliancewithlaws,

regulations, and standards.

Determine fraud risk tolerance.

Examinethesuitabilityofexistingfraudcontrolsandprioritizeresidualfraudrisks.

Documenttheprogram’sfraudriskprole.

Table 2: Leading Practices for Planning and Conducting Fraud Risk Assessments

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

2

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

12

Assess

2.1 Plan Regular Fraud Risk Assessments

That Are Tailored to the Program

Federal Internal Control Standards requires managers to assess

fraud risks and consider the potential for internal and external

fraud when identifying, analyzing, and responding to risks.

29

As noted, a leading practice in fraud risk management is for

managers to dedicate an entity to manage this process. An

effective antifraud entity tailors the approach for carrying out

fraud risk assessments to the program. Factors such as size,

resources, maturity of the agency or program, and experience

in managing risks can influence how the entity plans the

fraud risk assessment. For instance, an agency may have

enterprise-wide or other risk management activities, such as

processes to assess risks that affect operations or compliance

with laws. These activities can inform the specific approach

taken for assessing fraud risks. In addition, a program

may have experienced a recent structural change, or added

new services, which could necessitate more-frequent risk

assessments.

30

The factors noted above may also affect the frequency with

which antifraud entities update the fraud risk assessment. In

general, allowing extended periods of time to pass between

fraud risk assessments could result in control activities that

do not effectively address the program’s risks. According

to experts we interviewed, the frequency of updates can

range from 1 to 5 years, and one company suggested

quarterly reviews of the assessment. While the timing can

vary, effective antifraud entities plan to conduct fraud risk

assessments at regular intervals and when there are changes

to the program or operating environment, as fraud risk

assessments are iterative and not meant to be onetime

exercises. In commenting on a draft of the Framework,

officials representing a task force sponsored by COSO

and ACFE said the frequency of fraud risk assessments is

a function of need and not just a matter of demonstrating

compliance with standards.

Antifraud entities that effectively plan fraud risk assessments

identify specific tools, methods, and sources for gathering

information about fraud risks. This includes data on

fraud schemes and trends from monitoring and detection

activities. For instance, programs may develop surveys, or

add questions to existing surveys that specifically address

fraud risks and related control activities. In some programs,

it may be possible to conduct focus groups or review

documentation from reporting mechanisms, such as hotline

reports and referrals, to identify fraud risks affecting the

program. In addition, antifraud entities may engage relevant

stakeholders in one-on-one interviews or brainstorming

sessions about the types of fraud risks. A leading practice

for involving stakeholders in this process is to include

individuals responsible for the design and implementation of

the program’s fraud controls. This could include a variety of

internal and external stakeholders, such as general counsel,

contractors, or other external entities with knowledge about

emerging fraud risks or responsibilities for specific control

activities. In addition, the OIG and its work may inform the

fraud risk assessment process and help managers to identify

fraud risks. However, the OIG itself, as indicated in Federal

Internal Control Standards, should not lead or facilitate the

fraud risk assessments, in order to preserve its independence

when reviewing the program’s activities.

31

2.2 Identify and Assess Risks to Determine

the Program’s Fraud Risk Profile

Managers who effectively assess fraud risks attempt to fully

consider the specific fraud risks the agency or program

faces, analyze the potential likelihood and impact of fraud

schemes, and then ultimately document prioritized fraud

risks. Moreover, managers can use the fraud risk assessment

process to determine the extent to which controls may no

longer be relevant or cost-effective.

32

There is no universally

accepted approach for conducting fraud risk assessments,

since circumstances between programs vary; however,

assessing fraud risks generally involves the following five

actions:

33

1. Identify inherent fraud risks affecting the program:

34

Using methodologies discussed above, managers determine

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

13

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Assess

where fraud can occur and the types of internal and external

fraud risks the program faces, such as fraud related to

financial reporting, misappropriation of assets, corruption,

and nonfinancial forms of fraud.

35

These broad categories

of fraud encompass specific fraudulent schemes related to

contracting, grant-making, beneficiary payments, payroll

payments, and other areas of government activity. Further,

according to Federal Internal Control Standards, managers

may consider factors that are specific to fraud risks, including

incentives, opportunity, and rationalization to commit

fraud.

36

2. Assess the likelihood and impact of inherent fraud risks:

Managers may conduct quantitative or qualitative

assessments, or both, of the likelihood and impact of

inherent risks on the program’s objectives.

37

The specific

methodology managers use to assess fraud risks can vary

by program because of differences in missions, activities,

capacity, and other factors.

38

For instance, quantitative

methodologies for analyzing the likelihood and impact

of fraud involve statistical analysis, such as estimating

the frequency of fraud and amount of losses based on a

statistically valid sample or historical data of detected fraud.

These quantitative techniques are generally more precise

than qualitative methods, but they require resources and

expertise to successfully implement, and may pose challenges

for some managers, given the hidden nature of fraud (see app.

II for further discussion on challenges of measuring fraud).

Managers who effectively employ these techniques involve

qualified specialists, such as statisticians and subject-matter

experts, to provide expertise and guidance.

When resource constraints, available expertise, or other

circumstances prohibit the use of statistical analysis for

assessing fraud risks, other quantitative or qualitative

techniques can still be informative.

39

For example, risk

scoring quantifies the likelihood and impact of risks,

and preferably uses an objective method in which the

intervals between a score have meaning, such as using

numeric rankings of 1 to 5 that indicate “rare” to “almost

certain” for likelihood and “immaterial” to “extreme” for

impact. These rankings can then be used to understand

the overall significance of the risk on a similar five-point

scale that represents, for instance, “very low” to “very

high” (see fig. 3 later in this section for an illustration of

this concept).

In addition to financial impacts, fraud risks can have an

effect on the program’s reputation and compliance with

laws or regulations, and effective managers consider these

nonfinancial impacts during the assessment process.

40

For

example, managers may rank a particular type of fraud

risk higher than other types of fraud if they perceive its

impact on the program’s reputation to be greater if it were

to occur.

3. Determine fraud risk tolerance: According to Federal

Internal Control Standards, risk tolerance is the acceptable

level of variation in performance relative to the achievement

of objectives.

41

In the context of fraud risk management,

if the objective is to mitigate fraud risks—in general, to

have a very low level of fraud—the risk tolerance reflects

managers’ willingness to accept a higher level of fraud

risks.

42

Managers’ defined risk tolerance may depend on the

circumstances of individual programs and other objectives

beyond mitigation of fraud risks. The following text box

provides an illustrative example of risk tolerance applied to

a program that provides disaster assistance.

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

14

Assess

When responding to natural disasters, an assistance program has various control activities to prevent and detect

fraudulentapplicationsforitsservices,whichincludeprovidingnancialassistancefortemporaryhousingtopeople

whosehomesweredamagedordestroyed.Managersmaygenerallydenetheirrisktoleranceas“verylow”withregard

to providing temporary housing assistance to potentially fraudulent applicants. Therefore, they require all applicants to

undergo a home inspection to verify damage prior to the provision of any funds, since the inspections are a control activity

that provides a high level of certainty that the assistance is actually going to those in need.

However, managers may have a higher fraud risk tolerance, such as “low” rather than “very low,” for making payments

to potentially fraudulent applicants if the individuals live in a severely damaged area, since individuals in these areas

are likely to have an urgent need for temporary housing assistance. In such circumstances, managers may weigh the

program’sotheroperationalobjectiveofexpeditiouslyprovidingassistanceagainsttheobjectiveofloweringthelikelihood

of fraud, because activities to lower the risk related to fraudulent applications, such as conducting inspections, may cause

delays in service. Given a “low” fraud risk tolerance, as opposed to “very low,” a manager may decide to postpone or

foregohomeinspections,whichmaybetime-consumingordifculttoconductininaccessibleareas.Instead,themanager

may allocate resources to a control activity with a lower level of certainty than inspections, such as using geospatial

imagery to identify severely damaged areas and make eligibility determinations.

Figure3illustratesconceptsdescribedsofarwithatwo-dimensionalriskmatrix,acommontechniquemanagersmay

employ to visually plot risks according to their likelihood and impact.

a

Asnoted,thespecicmethodologymanagersuse

to assess fraud risks can vary. This particular technique is useful for engaging individuals who are knowledgeable about a

program, such as “front line” staff responsible for implementing control activities, and for helping managers understand the

linkbetweenspecicrisksandtheirimpact.

b

Therstmatrixillustratesarisktoleranceof“verylow”andthesecondmatrix

showsa“low”risktolerance,asdiscussedintheexampleabove.Seethe“DesignandImplement”sectionforfurther

discussiononpotentialresponsestofraudrisksthateitherexceedorarewithintherisktolerance.

Example of Risk Tolerance and Risk Matrices in the Context of Natural Disaster Assistance

Figure 3: Example of Two-Dimensional Risk Matrices

Likelihood

Impact

1 4 52 3

1

4

5

2

3

Within

Tolerance

Likelihood

Impact

1 4 52 3

1

4

5

2

3

Within

Tolerance

Exceeds

Tolerance

Exceeds

Tolerance

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

Risk Tolerance

Risk Significance

Very low risk tolerance Low risk tolerance

VERY LOW LOW MEDIUM HIGH VERY HIGH

a

Whenusingthismethod,risksaremappedontothematrixbasedonarankedscalethatgenerallyindicatesrisksonacontinuumoflowtohighrisks.Risksthat

fall in the upper right quadrant are the most likely to occur and have the greatest consequences for the program, compared to risks that fall into the lower left

quadrant.Whenrisksareplottedtogether,managerscanquicklydeterminewhichoneshavetoppriorityandbetterunderstandlinkagesbetweenspecicrisks.

As noted in Federal Internal Control Standards, managers may also consider correlations between risks, regardless of whether they choose to analyze risks on

an individual basis or as categories of risks (see GAO-14-704G, 7.07).

b

Ariskmatrixandotherapproachesforassessingfraudrisks,suchassurveys,arebasedonperceptionsandthereforetheymaynotpreciselyreecttheactual

likelihoodorfullimpactofthefraudrisks.Fraudriskassessmentsthatinvolverelevantinternalandexternalstakeholdersaremorelikelytobesuccessfuland

reectacompleteunderstandingoffraudrisksandcontrolvulnerabilitieswithinanagency.

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

15

Assess

The text box above describes risk tolerance in qualitative

terms; however, programs may also consider quantifying risk

tolerances to the extent possible. For instance, a quantified

risk tolerance could express managers’ willingness to tolerate

an estimated amount of potentially fraudulent activity,

given resource constraints in eliminating all fraud risks.

Regardless of the approach, managers should consider

defining risk tolerances that are specific and measurable,

as noted in Federal Internal Control Standards.

43

Moreover,

according to our focus-group participants, eliminating

fraud risk is not a realistic goal, and therefore effective

managers define and document their level of tolerable

fraud risk.

4. Examine the suitability of existing fraud controls

and prioritize residual fraud risks: Managers consider

the extent to which existing control activities mitigate

the likelihood and impact of inherent risks and whether

the remaining risks exceed managers’ tolerance.

44

The

aforementioned actions for assessing risks focused on

identifying and analyzing inherent fraud risks. At this

stage, managers focus on connecting existing fraud risk

management activities and controls to identified risks in

order to further understand the likelihood and impact of

the fraud risks affecting the program. The risk that remains

after inherent risks have been mitigated by existing control

activities is called residual risk. This part of the fraud

risk assessment process can help managers identify areas

where existing control activities are not suitably designed

or implemented to reduce risks to a tolerable level. Based

on this analysis and defined risk tolerance, managers then

rank residual fraud risks in order of priority, and determine

their responses, if any, to mitigate the likelihood and

impact of residual risks that exceed their risk tolerance (see

the “Design and Implement” section). During this process,

managers can also identify the responsible internal and

external entities, or “owners,” of the control activities that

are meant to reduce fraud risks.

5. Document the program’s fraud risk profile: Effectively

assessing fraud risks involves documenting the key findings

and conclusions from the actions above, including the

analysis of the types of internal and external fraud risks, their

perceived likelihood and impact, managers’ risk tolerance,

and the prioritization of risks. We refer to the summation

of these findings as the program’s “fraud risk profile” (see

app. V for an example of a fraud risk profile). The fraud risk

profile is an essential piece of an overall antifraud strategy

and can inform the specific control activities managers

design and implement, as described in the next section.

Figure 4 summarizes the key elements of the fraud risk

assessment process.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

16

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Assess

Document the program’s fraud risk profile

Identify inherent fraud risks affecting the program

1

2

3

4

5

Inherent Risks

Universe of Potential Fraud Risks

Prioritized

Residual

Risks

Managers determine where fraud can occur and the types of fraud the program

faces, such as fraud related to financial reporting, misappropriation of assets,

or corruption. Managers may consider factors that are specific to fraud risks,

including incentives, opportunity, and rationalization to commit fraud.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government,

a

risk tolerance is the acceptable level of variation in performance relative

to the achievement of objectives. In the context of fraud risk management,

if the objective is to mitigate fraud risks—in general, to have a very low level

of fraud—the risk tolerance reflects managers’ willingness to accept

a higher level of fraud risks, and it may vary depending on the

circumstances of the program.

Effectively assessing fraud risks involves documenting the key findings

and conclusions from the actions above, including the analysis of the

types of fraud risks, their perceived likelihood and impact, risk tolerance,

and the prioritization of risks.

Determine fraud risk tolerance

Managers consider the extent to which existing control activities mitigate

the likelihood and impact of inherent risks. The risk that remains after

inherent risks have been mitigated by existing control activities is called

residual risk. Managers then rank residual fraud risks in order of priority,

using the likelihood and impact analysis, as well as risk tolerance, to inform

prioritization.

Examine the suitability of existing fraud

controls and prioritize residual fraud risks

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

Assess the likelihood and impact of

inherent fraud risks

Managers conduct quantitative or qualitative assessments, or both, of the

likelihood and impact of inherent risks, including the impact of fraud risks on

the program’s finances, reputation, and compliance. The specific methodology

managers use to assess fraud risks can vary by program because of

differences in missions, activities, capacity, and other factors.

Figure 4: Key Elements of the Fraud Risk Assessment Process

a

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014), 6.08.

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

17

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Design and Implement

DesignandImplementaStrategywithSpecicControlActivitiestoMitigateAssessed

Fraud Risks and Collaborate to Help Ensure Effective Implementation

3.1 Determine Risk Responses and Document an Antifraud Strategy Based on the Fraud Risk Prole

Usethefraudriskproletohelpdecidehowtoallocateresourcestorespondtoresidualfraudrisks.

Develop, document, and communicate an antifraud strategy to employees and stakeholders that describes the program’s

activities for preventing, detecting, and responding to fraud, as well as monitoring and evaluation.

Establish roles and responsibilities of those involved in fraud risk management activities, such as the antifraud entity

andexternalpartiesresponsibleforfraudcontrols,andcommunicatetheroleoftheOfceofInspectorGeneral(OIG)to

investigate potential fraud.

Create timelines for implementing fraud risk management activities, as appropriate, including monitoring and evaluations.

Demonstratelinkstothehighestinternalandexternalresidualfraudrisksoutlinedinthefraudriskprole.

Link antifraud efforts to other risk management activities, if any.

3.2 Design and Implement Specic Control Activities to Prevent and Detect Fraud

Focusonfraudpreventionoverdetectionandresponsetoavoida“pay-and-chase”model,totheextentpossible.

Considerthebenetsandcostsofcontrolactivitiestoaddressidentiedresidualrisks.

Design and implement the following control activities to prevent and detect fraud:

a

• data-analytics activities,

• fraud-awareness initiatives,

• reporting mechanisms, and

• employee-integrity activities.

3.3 Develop a Plan Outlining How the Program Will Respond to Identied Instances of Fraud

Developaplanoutlininghowtheprogramwillrespondtoidentiedinstancesoffraudandensuretheresponseisprompt

and consistently applied.

Refer instances of potential fraud to the OIG or other appropriate parties, such as law-enforcement entities or the

Department of Justice, for further investigation.

3.4 Establish Collaborative Relationships with Stakeholders and Create Incentives to Help

Ensure Effective Implementation of the Antifraud Strategy

Establishcollaborativerelationshipswithinternalandexternalstakeholders,includingotherofceswithintheagency;

federal,state,andlocalagencies;private-sectorpartners;law-enforcemententities;andentitiesresponsibleforcontrol

activities to, among other things,

• share information on fraud risks and emerging fraud schemes, and

• share lessons learned related to fraud control activities.

Collaborate and communicate with the OIG to improve understanding of fraud risks and align efforts to address fraud.

Create incentives for employees to manage risks and report fraud, including

• creating performance metrics that assess fraud risk management efforts and employee integrity, particularly for

managers;and

• balancingfraud-specicperformancemetricswithothermetricsrelatedtoemployees’duties.

Provideguidanceandothersupportandcreateincentivestohelpexternalparties,includingcontractors,effectivelycarry

out fraud risk management activities.

Table 3: Leading Practices for Designing and Implementing an Antifraud Strategy with

Control Activities

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

a

See table 5 for additional leading practices related to each of these control activities.

3

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

18

3.1 Determine Risk Responses and

Document an Antifraud Strategy Based on

the Fraud Risk Profile

Federal Internal Control Standards requires managers to

design a response to analyzed risks. Managers should consider

the likelihood and impact of the risks, as well as their defined

risk tolerance. These are key elements of a program’s fraud

risk profile, as previously discussed. Effective managers of

fraud risks use the program’s fraud risk profile to help decide

how to allocate resources to respond to residual fraud risks.

45

The responses to fraud risks may include actions to accept,

reduce, share, or avoid the risk.

46

In general, managers accept

certain risks that are within their defined risk tolerance and

take one of the other three actions in response to prioritized

residual fraud risks that exceed their defined risk tolerance

(see fig. 5). Specifically, managers may allocate resources to

prevent or detect fraud risks that exceed their risk tolerance,

but they may decide not to allocate resources to further

reduce unlikely, low-impact risks that fall within their risk

tolerance. Moreover, while managers may “accept” certain

fraud risks, responding appropriately to instances of actual

fraud is essential for ensuring the continued effectiveness of

fraud risk management activities, as discussed later in this

section.

Figure 5: Potential Responses to Fraud Risks Based on Assessed

Likelihood, Impact, and Risk Tolerance

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Design and Implement

Likelihood

Impact

1 4 52 3

1

4

5

2

3

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

Risk Tolerance

Risk Significance

VERY LOW LOW MEDIUM HIGH VERY HIGH

Accept

Reduce or Share

Avoid

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

19

Design and Implement

Managers who effectively manage fraud risks develop and

document an antifraud strategy that describes the program’s

approach for addressing the prioritized fraud risks identified

during the fraud risk assessment. The antifraud strategy

describes existing fraud control activities as well as any new

control activities a program may adopt to address residual

fraud risks. Federal Internal Control Standards notes that

documentation of the internal-control system helps establish

and communicate to employees the “who, what, when,

where, and why” of control implementation.

47

Managers

may decide to develop an agency-wide antifraud strategy,

or direct individual programs to develop a strategy at the

program level. Similar to the fraud risk assessment process,

factors such as a program’s size, complexity, maturity, and

types of fraud risks can inform this decision. Regardless of

their application across an agency or for specific programs,

effective antifraud strategies reflect the leading practices

described in table 4.

Who is responsible for fraud risk

management activities?

Establish roles and responsibilities of those involved in fraud risk

managementactivities,suchastheantifraudentityandexternal

parties responsible for fraud controls, and communicate the role of

theOfceofInspectorGeneral(OIG)toinvestigatepotentialfraud.

What is the program doing to

manage fraud risks?

Describe the program’s activities for preventing, detecting, and

responding to fraud, as well as monitoring and evaluation.

a

When is the program implementing

fraud risk management activities?

Create timelines for implementing fraud risk management

activities, as appropriate, including monitoring and evaluations.

Where is the program focusing its

fraud risk management activities?

Demonstratelinkstothehighestinternalandexternalresidual

fraudrisksoutlinedinthefraudriskprole.

Why is fraud risk management

important?

Communicate the antifraud strategy to employees and other

stakeholders, and link antifraud efforts to other risk management

activities, if any.

Table 4: Key Elements of an Antifraud Strategy

Source: GAO. | GAO-15-593SP

a

According to Federal Internal Control Standards, control activities are the policies, procedures, techniques, and mechanisms that enforce managers’ directives to

achieve the program’s objectives and address related risks. Broadly speaking, the antifraud strategy itself can be viewed as a preventive control activity, although it

caninformothercontrolactivities,suchasthecontentoffraud-awarenesstrainingorthedesignofsystemeditchecks.Theantifraudstrategydescribesexistingfraud

control activities, as well as any new control activities a program may have planned or adopted to address any residual fraud risks.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

20

3.2 Design and Implement Specific Control

Activities to Prevent and Detect Fraud

As part of the antifraud strategy, managers who effectively

manage fraud risks design and implement specific control

activities—including policies, procedures, techniques,

and mechanisms—to prevent and detect potential fraud.

In addition to designing and implementing new control

activities, managers may also revise existing control activities

if they determine, as part of the fraud risk assessment

process, that certain controls are not effectively designed

or implemented to reduce the likelihood or impact of an

inherent fraud risk to a tolerable risk level.

As discussed, while fraud control activities can be

interdependent and mutually reinforcing, preventive

activities generally offer the most cost-effective investment

of resources. Therefore, effective managers of fraud risks

focus their efforts on fraud prevention in order to avoid

a costly “pay-and-chase” model, to the extent possible.

In addition, automated control activities (e.g., automated

data-analytic techniques) tend to be more reliable than

manual control activities (e.g., document reviews) because

they are less susceptible to human error and are typically

more efficient. Further, experts from one private-sector

organization we met with noted controls that are targeted

to specific risks may be more expensive than agency-wide

controls, such as requiring new employees to sign an

antifraud policy. However, targeted controls may lower the

cost of identifying each instance of fraud because they are

more effective.

When developing an antifraud strategy, managers also

consider the benefits and costs of control activities to

address identified residual risks, such as the benefit to the

program of reducing the likelihood or impact of a fraud risk

and the direct financial cost of the control to the program.

Federal Internal Control Standards states that managers may

decide how to evaluate the benefits versus costs of various

approaches to implementing an effective internal control

system.

48

Approaches for considering the benefits and costs

of control activities to address identified fraud risks include

benefit-cost analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis.

49

The

text box below provides additional information on using

these approaches.

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Design and Implement

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs GAO-15-593SP

21

E

N

V

I

R

O

N

M

E

N

T

Design and Implement

Benet-costanalysisinvolvesthesystematicidenticationandmonetizationofallbenetsandcosts

associatedwithdesigningandimplementingacontrolactivity,aswellashowthosebenetsandcostsare

distributedacrossdifferentgroups.Basedonabenet-costanalysis,managersmaydecidenottoimplement

certaincontrolactivitiesforwhichtheestimatedbenetsdonotexceedthecosts.Forexample,managers

may decide not to conduct payment-recapture audits to recover improper payments if it is likely that the

costsincurredtoidentifyandrecovertheoverpaymentswillbegreaterthantheexpectedrecoveries.

a

While

benet-costanalysiscanhelpmanagersdeterminewhetherbenetsofacontrolactivityexceeditscosts,

managersmayfacechallengesinmonetizingcertainbenetsandcosts.

b

Forexample,inadditiontodirect

nancialbenetsandcoststotheprogram,fraudcontrolsmayresultinadditionalbenets,suchasthevalue

of deterred fraud, or other costs, such as delays for legitimate applicants. In such circumstances, cost-

effectivenessanalysis—amethodologyfordeterminingthecosttoachieveaparticularobjective,expressedin

nonmonetary terms—can be appropriate.

Managersmayconsidercost-effectivenessanalysiswhenthebenetsfromcompetingalternativesare

the same or where a law or policy requires a program to achieve a particular objective.

c

For instance, if a

program’spoliciesrequirevericationthatapplicantsprovideavalidaddressinordertoenrollinaprogramor

receivebenets,managersmayusecost-effectivenessanalysistocomparealternativemeansofachieving

thisobjective.Inthisexample,theanalysiscouldweightwoalternatives,suchasusingfederalgovernment

databases to electronically verify addresses and paying inspectors to physically verify each address, in order

todeterminetheoptionwiththelowestcostperinvalidaddressidentied.Asillustratedbythisexample,

cost-effectiveness analysis enables managers to assess alternatives without having to calculate the monetary

valueofthebenetsofeachoption.

a

However, OMB requires an agency that determines that it would be unable to conduct a cost-effective payment-recapture audit program for certain

programsthatexpendmorethan$1milliontonotifyOMBandtheagency’sInspectorGeneralofthisdecisionandincludeanyanalysisusedbythe

agency to reach this decision. OMB may review these materials and determine that the agency should conduct a payment-recapture audit to review these

programsandactivities.OfceofManagementandBudget,Requirements for Effective Estimation and Remediation of Improper Payments, Circular No.

A-123, app. C (Washington, D.C.: 2014).

b

See app. II for further discussion of the challenges related to measuring fraud.

c

OMBguidelinesstatethatbenet-costanalysisisthepreferredmethodologyforanalyzinggovernmentprograms,butnotethatcost-effectiveness

analysiscanbeappropriateinthesecircumstances.Inaddition,theguidelinesnotethatacomprehensiveenumerationofthedifferenttypesofbenets