Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

For use at 11:00 a.m. EDT

June 17, 2022

Monetary Policy rePort

June 17, 2022

Letter of transmittaL

B G

F R S

Washington, D.C., June 17, 2022

T P S

T S H R

The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to

section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act.

Sincerely,

Jerome H. Powell, Chair

Statement on Longer-run goaLS and monetary PoLicy Strategy

Adopted effective January24, 2012; as reafrmed effective January25, 2022

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is rmly committed to fullling its statutory mandate from

the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The

Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity

facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and businesses, reduces economic and nancial

uncertainty, increases the eectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability,

which are essential in a democratic society.

Employment, ination, and long-term interest rates uctuate over time in response to economic and nancial

disturbances. Monetary policy plays an important role in stabilizing the economy in response to these

disturbances. The Committee’s primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy is through changes

in the target range for the federal funds rate. The Committee judges that the level of the federal funds rate

consistent with maximum employment and price stability over the longer run has declined relative to its

historical average. Therefore, the federal funds rate is likely to be constrained by its eective lower bound

more frequently than in the past. Owing in part to the proximity of interest rates to the eective lower bound,

the Committee judges that downward risks to employment and ination have increased. The Committee is

prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.

The maximum level of employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal that is not directly measurable

and changes over time owing largely to nonmonetary factors that aect the structure and dynamics of the

labor market. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to specify a xed goal for employment; rather, the

Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its

maximum level, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The

Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments.

The ination rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee

has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for ination. The Committee rearms its judgment that ination

at the rate of 2percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The

Committee judges that longer-term ination expectations that are well anchored at 2percent foster price

stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhance the Committee’s ability to promote maximum

employment in the face of signicant economic disturbances. In order to anchor longer-term ination

expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve ination that averages 2percent over time, and

therefore judges that, following periods when ination has been running persistently below 2percent,

appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve ination moderately above 2percent for some time.

Monetary policy actions tend to inuence economic activity, employment, and prices with a lag. In setting

monetary policy, the Committee seeks over time to mitigate shortfalls of employment from the Committee’s

assessment of its maximum level and deviations of ination from its longer-run goal. Moreover, sustainably

achieving maximum employment and price stability depends on a stable nancial system. Therefore, the

Committee’s policy decisions reect its longer-run goals, its medium-term outlook, and its assessments of

the balance of risks, including risks to the nancial system that could impede the attainment of the

Committee’s goals.

The Committee’s employment and ination objectives are generally complementary. However, under

circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it takes into account

the employment shortfalls and ination deviations and the potentially dierent time horizons over which

employment and ination are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate.

The Committee intends to review these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its annual

organizational meeting each January, and to undertake roughly every 5years a thorough public review of its

monetary policy strategy, tools, and communication practices.

Contents

note: This report reects information that was publicly available as of 4 p.m. EDT on June15, 2022.

Unless otherwise stated, the time series in the gures extend through, for daily data, June14, 2022; for

monthly data, May2022; and, for quarterly data, 2022:Q1. In bar charts, except as noted, the change for a

given period is measured to its nal quarter from the nal quarter of the preceding period.

For gures 23, 36, and 42, note that the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index, the S&P 500 Index, and the Dow Jones Bank Index are

products of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its afliates and have been licensed for use by the Board. Copyright © 2022 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a

division of S&P Global, and/or its afliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution, reproduction, and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without

written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more information on any of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices, please visit www.spdji.com.

S&P

®

is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, and Dow Jones

®

is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings

LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates, nor their third-party licensors make any representation or

warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent, and neither

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates, nor their third-party licensors shall have any liability for any errors,

omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

Summary .................................................................1

Recent Economic and Financial Developments ................................... 1

Monetary Policy

........................................................... 3

Special Topics

............................................................. 3

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial Developments .....................5

Domestic Developments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Financial Developments

.................................................... 27

International Developments

................................................. 35

Part 2: Monetary Policy ..................................................43

Part 3: Summary of Economic Projections

................................51

Abbreviations ............................................................69

List of Boxes

Developments in Global Supply Chains ......................................... 8

Developments in Employment and Earnings across Groups

......................... 14

Developments Related to Financial Stability

..................................... 31

Global Ination

.......................................................... 37

Monetary Policy in Foreign Economies

......................................... 39

Monetary Policy Rules in the Current Environment

................................ 46

Developments in the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet and Money Markets

.............. 49

Forecast Uncertainty

....................................................... 66

1

summary

In the rst part of the year, ination remained

well above the Federal Open Market

Committee’s (FOMC) longer-run objective

of 2percent, with some ination measures

rising to their highest levels in more than

40years. These price pressures reect supply

and demand imbalances, higher energy and

food prices, and broader price pressures,

including those resulting from an extremely

tight labor market. In the labor market,

demand has remained strong, and supply

has increased only modestly. As a result, the

unemployment rate fell noticeably below the

median of FOMC participants’ estimates of

its longer-run normal level, and nominal wages

continued to rise rapidly. Although overall

economic activity edged down in the rst

quarter, household spending and business xed

investment remained strong. The most recent

indicators suggest that private xed investment

may be moderating, but consumer spending

remains strong.

In response to sustained inationary pressures

and a strong labor market, the FOMC has

been adjusting its policies and communications

since last fall. At its March meeting, the

FOMC raised the target range for the federal

funds rate o the eective lower bound to ¼ to

½percent. The Committee continued to raise

the target range in May and June, bringing

it to 1½ to 1¾percent following the June

meeting, and indicated that ongoing increases

are likely to be appropriate. The Committee

ceased net asset purchases in early March and

began reducing its securities holdings in June.

The Committee is acutely aware that high

ination imposes signicant hardship,

especially on those least able to meet the

higher costs of essentials. The Committee’s

commitment to restoring price stability—

which is necessary for sustaining a strong labor

market—is unconditional.

Recent Economic and Financial

Developments

Ination. Consumer price ination, as

measured by the 12-month change in the

price index for personal consumption

expenditures (PCE), rose from 5.8percent

in December2021 to 6.3percent in April, its

highest level since the early 1980s and well

above the FOMC’s objective of 2percent.

This increase was driven by an acceleration of

retail food and energy prices, reecting further

increases in commodity prices due to Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine. The 12-month measure

of ination that excludes the volatile food and

energy categories (so-called core ination)

rose initially and then fell back to 4.9percent

in April, unchanged from last December.

Three-month measures of core ination have

softened since December but remain far

above levels consistent with price stability.

Measures of near-term ination expectations

continued to rise markedly, while longer-term

expectations moved up by less.

The labor market. Demand for labor continued

to outstrip available supply across many parts

of the economy, and nominal wages continued

to increase at a robust pace. While labor

demand remained very strong, labor supply

increased only modestly. As a result, the labor

market tightened further between December

and May, with job gains averaging 488,000per

month and the unemployment rate falling

from 3.9percent to 3.6percent—just above the

bottom of its range over the past 50years.

Economic activity. Real gross domestic

product (GDP) is reported to have surged at a

6.9percent annual rate in the fourth quarter of

2021 and then to have declined at a 1.5percent

annual rate in the rst quarter. The large

swings in growth rates reected uctuations

in the volatile expenditure categories of net

2 SUMMARY

exports and inventory investment. Abstracting

from these volatile components, growth in

private domestic nal demand (consumer

spending plus residential and business xed

investment—a measure that tends to be more

stable and better reects the strength of

overall economic activity) was strong in the

rst quarter, supported by some unwinding

of supply bottlenecks and a further reopening

of the economy. The most recent indicators

suggest that private xed investment may be

moderating, but consumer spending remains

strong. As a result, real GDP appears on track

to rise moderately in the second quarter.

Financial conditions. Financial conditions have

tightened signicantly this year. The expected

path of the federal funds rate over the next few

years shifted up substantially, and yields on

nominal Treasury securities across maturities

have risen considerably since late February

amid sustained inationary pressures and

associated expectations for further monetary

policy tightening. Equity prices were volatile

and declined sharply, on net, while corporate

bond yields increased substantially and spreads

increased notably, partly reecting some

concerns about the future corporate credit

outlook. Mortgage rates also rose sharply. In

turn, tighter nancial conditions may have

begun to weigh on some nancing activity. On

the business side, nonnancial corporate bond

issuance was solid in the rst quarter but slowed

somewhat in April and May, with speculative-

grade bond issuance being particularly

weak. That said, the growth of bank loans to

businesses picked up, and business credit quality

has remained strong thus far. For households,

mortgage originations declined materially.

Nevertheless, mortgage credit remained

broadly available for a wide range of potential

borrowers. For other consumer loans (such as

auto loans and credit cards), credit standards

eased somewhat further or changed little, and

credit outstanding grew briskly.

Financial stability. Despite experiencing

a series of adverse shocks—higher-than-

expected ination, the ongoing supply

disruptions related to COVID-19, and Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine—the nancial system

has been resilient, though portions of the

commodities markets temporarily experienced

elevated levels of stress. The drop in equity

prices and rising bond spreads suggest that

valuation pressures in corporate securities

markets have eased some from their previously

elevated levels, but real estate prices have

risen further this year. While business and

household debt has been growing solidly, the

ratio of credit to GDP has decreased to near

pre-pandemic levels and most indicators of

credit quality remained robust, suggesting that

vulnerabilities from nonnancial leverage are

moderate. Large bank capital ratios dipped

in the rst quarter, but overall leverage in the

nancial sector appears moderate and little

changed this year. Recent strains experienced

in markets for stablecoins—digital assets that

aim to maintain a stable value relative to a

national currency or other reference assets—

and other digital assets have highlighted the

structural fragilities in that rapidly growing

sector. A few signs of funding pressures

emerged amid the geopolitical tensions,

particularly in commodities markets. However,

broad funding markets proved resilient,

and with direct exposures of U.S. nancial

institutions to Russia and Ukraine being small,

nancial spillovers have been limited to date.

International developments. Economic

activity has continued to recover in many

foreign economies, albeit with new signicant

headwinds from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

and COVID lockdowns in China. These

headwinds have, on net, pushed commodity

prices higher, worsened supply disruptions, and

lowered household and business condence,

thus damping the rebound in foreign economic

activity. As in the United States, consumer

price ination abroad is high and has

continued to rise in many economies, boosted

by higher energy, food, and other commodity

prices as well by supply chain constraints. In

response, many foreign central banks have

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 3

raised policy rates, and some have started to

reduce the size of their balancesheets.

Foreign nancial conditions have tightened

notably since the beginning of the year, in part

reecting the tightening in foreign monetary

policy and concerns about persistently high

ination. Sovereign bond yields in many

advanced foreign economies rose. Foreign

risky asset prices declined, also driven by

downside risks to the growth outlook amid

the lockdowns in China and Russia’s invasion

of Ukraine. The trade-weighted value of the

dollar appreciated notably.

Monetary Policy

In response to signicant ongoing ination

pressures and the tightening labor market, the

Committee has been adjusting its policies and

communications since last fall. The Committee

wound down net purchases of securities and

began reducing those securities holdings more

rapidly than expected, and also initiated a swift

increase in interest rates. Adjustments to both

interest rates and the balance sheet are playing

a role in rming the stance of monetary policy

in support of the Committee’s maximum-

employment and price-stability goals.

Interest rate policy. In March, after holding

the federal funds rate near zero since the

onset of the pandemic, the FOMC raised the

target range for that rate to ¼ to ½percent.

The Committee raised the target range again

in May and June, bringing it to the current

range of 1½ to 1¾percent, and conveyed

its anticipation that ongoing increases in the

target range will be appropriate.

Balance sheet policy. The Federal Reserve

began reducing its monthly net asset purchases

last November and accelerated the reductions

in December, bringing net purchases to an

end in early March. In January, the FOMC

issued a set of principles regarding its planned

approach for signicantly reducing the size of

the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. Consistent

with those principles, the Committee

announced in May its specic plans for

signicantly reducing its securities holdings

and that these reductions would begin on

June1.

1

The Committee acutely recognizes the

signicant hardship caused by elevated

ination, especially on those least able to meet

the higher costs of essentials. The Committee

is strongly committed to restoring price

stability, which is necessary for sustaining a

strong labor market.

Special Topics

Labor market disparities. The labor market

recovery over the past year and a half has

been robust and widespread as the labor

market eects of the pandemic have eased,

with particularly strong improvement among

groups that had suered the most. As a result,

employment and earnings of nearly all major

demographic groups are near or above their

levels before the pandemic, and employment

rates are again near multidecade highs.

However, there remain notable dierences in

employment and earnings across groups that

predate the pandemic.

Developments in global supply chains. Supply

chain bottlenecks remain a major impediment

for domestic and foreign rms. While U.S.

manufacturers have been recording solid

output growth for more than a year, order

backlogs and delivery times remain high, and

producer prices have risen rapidly. Further

risks to global supply chains abound. In

China, COVID-19 lockdowns drove the largest

monthly declines in industrial production there

since early 2020 while also disrupting internal

and international freight transportation. In

addition, the war in Ukraine continues to put

1. See the May4, 2022, press release regarding the

Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve’s

Balance Sheet, available at https://www.federalreserve.

gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20220504b.htm.

4 SUMMARY

upward pressure on energy and food prices

and has raised the risk of disruption in the

supply of inputs to some manufacturing

industries.

Monetary policy rules. Simple monetary policy

rules, which relate a policy interest rate to a

small number of other economic variables,

can provide useful guidance to policymakers.

Many simple policy rules prescribed strongly

negative values for the federal funds rate

during the pandemic-driven recession.

With ination running well in excess of the

Committee’s 2percent longer-run objective, a

strong U.S. economy, and tight labor market

conditions, the simple monetary policy rules

considered here call for raising the target range

for the federal funds rate signicantly.

Global ination. Ination abroad rose rapidly

over the past year, reecting soaring food and

commodity prices, pandemic-related supply

disruptions, and demand imbalances between

goods and services. The price pressures have

been amplied by the war in Ukraine and

COVID-19 lockdowns in China. Although

the recent ination surge was concentrated in

volatile components, such as food and energy,

price increases have broadened to core goods

and services.

Global monetary policy. With ination

rising sharply across the globe, many central

banks have tightened monetary policy.

Policy tightening started last year as some

emerging market central banks, particularly

those in Latin America, were concerned that

sharp increases in ination could become

entrenched in ination expectations. Since

fall 2021, many central banks in the advanced

foreign economies have also started tightening

monetary policy or are expected to do so soon,

and several central banks that had expanded

their balance sheets over the past two years are

now allowing them to shrink.

Developments in the Federal Reserve’s balance

sheet. Following the conclusion of net asset

purchases, the balance sheet remained stable

at around $9trillion. Alongside the removal of

policy accommodation—through actual and

expected increases in the policy rate—plans

for shrinking the size of the balance sheet

were announced in May and were initiated

in June. Despite the size of the balance sheet

remaining steady, reserve balances fell, in

large part because of increasingly elevated

take-up at the overnight reverse repurchase

agreement (ONRRP) facility, which reached a

record high of $2.2trillion. In an environment

of ample liquidity, limited Treasury bill

supply, and low repurchase agreement rates,

the ONRRP facility continued to serve its

intended purpose of helping to provide a oor

under short-term interest rates and to support

eective implementation of monetary policy.

5

Domestic Developments

Ination continued to run high . . .

After surging 5.8percent over 2021—the

largest increase since 1981—the price index

for personal consumption expenditures (PCE)

continued to post notable increases so far

this year, and the change over the 12 months

ending in April stood at 6.3percent (gure1).

This pace is well above the FOMC’s longer-run

objective of 2percent.

. . . reecting further large increases in

food and energy prices . . .

Grocery prices increased at a very rapid pace

of 10percent over the 12months ending in

April, more than 4percentage points faster

than over the 12 months ending in December

and the highest reading since 1981 (gure2).

Food commodity prices (such as wheat and

corn), which had already increased last year,

have risen further since Russia’s invasion of

Ukraine. At the same time, high fuel costs,

supply chain bottlenecks, and high wage

growth have also pushed up processing,

packaging, and transportation costs for food.

The PCE price index for energy increased

30percent over the 12 months ending in April,

Part 1

reCent eConomiC and finanCiaL deveLoPments

Excluding food

and energy

Trimmed mean

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

Percent change from year earlier

202220212020201920182017201620152014

1. Change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures

Monthly

Total

NOTE: The data extend through April 2022.

S

OURCE: For trimmed mean, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; for all

else, Bureau of Economic Analysis; all via Haver Analytics.

2. Personal consumption expenditures price indexes

Food and

beverages

4

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Percent change from year earlier

20

10

+

_

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

20222021202020192018

Percent change from year earlier

Energy

NOTE: The data are monthly and extend through April 2022.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Services

ex energy

and housing

Goods ex food,

beverages, and

energy

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

Percent change from year earlier

20222021202020192018

Monthly

Housing

services

NOTE: The data extend through April 2022.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

6 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

4

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

12-month percent change

202220212020201920182017201620152014

5. Nonfuel import price index

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data extend through April 2022.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

about the same pace as over the 12months

ending in December. Large increases in crude

oil and natural gas commodity prices have

boosted consumer prices for gasoline and

natural gas.

. . . which, in turn, partly reected rising

prices of commodities and imports

Because of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, oil

prices rose sharply in early March, reaching

eight-year highs (gure3). Prices remain

elevated and volatile, boosted by a European

Union embargo of Russian oil imports

but weighed down at times by concerns

about global economic growth. In addition,

producers in other countries are struggling to

ramp up oil production.

Nonfuel commodity prices also surged after

the invasion, with large increases in the

prices of both agricultural commodities and

industrial metals (gure4). Although the price

of industrial metals has declined recently,

agricultural prices remain elevated. Ukraine

and Russia are notable exporters of wheat,

Russia is a major exporter of fertilizer, and

higher energy prices are spilling over into the

agricultural sector. Export restrictions and

unfavorable weather conditions in several

countries have also boosted agricultural prices.

(See the box “Developments in Global Supply

Chains.”)

With commodity prices surging and foreign

goods prices on the rise, import prices

increased signicantly (gure5).

Excluding food and energy prices,

monthly ination readings have softened

since the turn of the year but remain

far above levels consistent with price

stability

Supply chain issues, hiring diculties, and

other capacity constraints have prevented

the supply of products from rising quickly

enough to satisfy continued strong demand,

resulting in large price increases for many

goods and services over the past year. After

excluding consumer food and energy prices,

Brent spot price

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Dollars per barrel

2007 2010 2013 2016 2019 2022

3. Spot and futures prices for crude oil

Weekly

24-month-ahead

futures contracts

N

OTE: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend through

June 10, 2022.

S

OURCE

: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

Agriculture

and livestock

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

Week ending January 3, 2014 = 100

2014 2015 2016 2017 20182019 2020 2021 2022

4. Spot prices for commodities

Weekly

Industrial metals

N

OTE: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend throug

h

June 10, 2022.

S

OURCE: For industrial metals, S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Index

Spot; for agriculture and livestock, S&P GSCI Agriculture & Livestock

Spot Index; both via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 7

the 12-month measure of core PCE ination

rose initially and then fell back to 4.9percent

in April, unchanged from December.

That said, monthly core ination readings

have softened noticeably since the start of the

year, with the three-month measure of core

PCE ination falling from an annual rate of

6.0percent last December to 4.0percent in

April. In particular, ination stepped down for

durable goods, likely reecting some easing in

supply constraints.

Nevertheless, the recent ination readings have

been mixed, remain far above levels consistent

with price stability, and are far from conclusive

evidence on the direction of ination. Unlike

durable goods price ination, core services

ination has not declined signicantly.

Housing service prices continue to rise at a

brisk pace, and increased demand for travel is

markedly pushing up ination rates for lodging

and airfares. More generally, rapid growth of

labor costs is putting upward pressure on the

prices of all labor-intensive services.

Measures of near-term ination

expectations continued to rise markedly,

while longer-term expectations moved up

by less

The rst half of 2022 saw further increases in

expectations of ination for the year ahead in

surveys of both consumers and professional

forecasters (gure6). In the University of

Michigan Surveys of Consumers, the median

value for ination expectations over the

next year jumped to 5.4percent in March,

its highest level since November1981, and

has moved sideways since then. A portion

of the upward movement so far this year

likely reects the war in Ukraine and the

accompanying increases in the prices of

commodities, especially those related to energy

and food.

Longer-term expectations, which are more

likely to inuence actual ination over time,

moved up by less and remained above pre-

pandemic levels. The Michigan survey’s

median ination expectation for the next

CIE, projected onto

10-year SPF

Michigan survey,

next 12 months

SPF, 10 years ahead

CIE, projected onto

Michigan, next 5 to 10 years

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

Percent

202220202018201620142012201020082006

6. Measures of ination expectations

Michigan survey,

next 5 to 10 years

N

OTE: The Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) data are

quarterly, begin in 2007:Q1, and extend through 2022:Q2. The data for

the Index of Common Ination Expectations (CIE) and the Michigan

survey are monthly and extend through June 2022; the June data for the

Michigan survey and the CIE are preliminary.

S

OURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers;

Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, SPF; Federal Reserve Board, CIE;

Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

8 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

mixed for bottlenecks in the transportation of goods.

The number of ships waiting for berths at West Coast

ports has declined noticeably, as port throughput has

remained high, although manufacturers continue to cite

logistics and transportation constraints as reasons for

loweroutput.

Bottlenecks in global production and transportation

remain a major impediment for both domestic and

foreign rms. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the

widespread COVID-19 lockdowns in China have

exacerbated strains in global supply networks and

have led to greater uncertainty about the timing of

improvement in supply conditions.

Despite this turbulence in the global supply

network, U.S. manufacturers have been recording

solid output growth for more than a year. There have

been gains in domestic motor vehicle production,

as the supply of semiconductors has recovered

somewhat ( gure A). In addition, survey results

suggest shorter supplier delivery times and lower order

backlogs relative to their late 2021 levels ( gure B).

Notwithstanding these improvements, backlogs and

delivery times for the sector remain elevated, and light

vehicle assemblies are still a bit below pre-pandemic

levels, with low dealer inventories continuing to

constrain sales. For some materials that had previously

been in short supply—such as lumber and steel—

prices have declined from notable highs. Even so,

the overall producer price index for manufacturing

in April was more than 18percent above its year-

earlier level ( gureC). Progress has been similarly

Developments in Global Supply Chains

(continued)

70

80

90

100

110

January 2020 = 100

Feb. Apr. Jun. Aug. Oct. Dec. Feb.Apr.

2021 2022

A. U.S. light motor vehicle production

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data extend through April 2022. The data are a

djusted

using Federal Reserve Board seasonal factors.

S

OURCE

: Ward’s Automotive Group, AutoInfoBank and

Intelligence

Data

Query; Chrysler Group LLC, North American Production Data

;

General

Motors Corporation, GM Motor Vehicle Assembly Productio

n

Data.

Order backlogs

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Diusion index

2022201720122007

B. Suppliers’ delivery times and order backlogs

Monthly

Delivery

times

N

OTE: Values greater than 50 indicate that more respondents reported

longer delivery times or order backlogs relative to a month earlier than

reported shorter delivery times or order backlogs.

S

OURCE:Institute for Supply Management, ISM Manufacturing Report

on Business.

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

20

Percent change from year earlier

202220212020201920182017

C. Producer price index for manufacturing

Monthly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 9

Risks to supply chain conditions abound, including

those arising from COVID-19 lockdowns in China

beginning in mid-March and the ongoing war in

Ukraine.

1

Committed to their zero-COVID strategy,

Chinese authorities ratcheted up restrictions quickly

in the face of rising cases of the Omicron variant,

which included a complete lockdown of Shanghai.

The containment strategy managed to reduce case

counts, allowing authorities to begin relaxing some

citywide restrictions in late April. The lockdowns drove

the largest monthly declines in Chinese activity since

early 2020, with industrial production dropping about

13percent between February and April ( gure D)

before recovering some in May. With severely disrupted

domestic logistics, supplier delivery times increased

sharply in April and continued increasing in May, but

not as strongly ( gure E). Chinese international trade

was also hit, contracting in the three months before

April ( gure F). As Chinese production continues to

recover, the associated rebound in trade ows may

further strain international transportation networks.

1. The July1 expiration of the contract between

dockworkers and West Coast port operators poses an

additional risk for shipping-related disruption.

Retail sales

16

12

8

4

+

_

0

4

8

12

Percent change

Jan. Mar. May July Sept. Nov.Jan.Mar.May

2021 2022

D. Chinese industrial production and retail sales

Monthly

Industrial production

N

OTE

: Industrial production data are adjusted using Federal Reserv

e

Board

seasonal factors. Retail sales data are seasonally adjusted by

the

National Bureau of Statistics of China.

S

OURCE

:National Bureau of Statistics of China via Haver Analytics

;

Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

50

55

60

65

70

Diusion index

2022202120202019

E. China’s purchasing managers index: Supplier delivery times

Monthly

N

OTE

: The series is seasonally adjusted. Values greater than 50

indicate

that more respondents reported longer delivery times relative to

a month earlier than reported shorter delivery times.

S

OURCE: Caixin; S&P Global; both via Haver Analytics.

Imports

50

+

_

0

50

100

150

200

Percent change

Jan. Mar. May July Sept. Nov. Jan. Mar. May

2021 2022

F. Nominal trade growth in China

Monthly

Exports

N

OTE

: All series are seasonally adjusted at an annual rate using

Federal Reserve Board seasonal factors. The data are 3-month moving

averages.

S

OURCE

: General Administration of Customs, China, via Haver

Analytics.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia is causing

economic hardship. For instance, the con ict has

disrupted global commodity markets in which Ukraine

and Russia account for signi cant shares of global

exports. Notably, energy prices have soared, as

(continued on next page)

10 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

increasing geopolitical tensions have put the supply

of Russian oil and gas to Europe at risk. Indeed,

Russian energy exports have already been falling amid

embargos on Russian oil, self-sanctioning by some

companies, transportation dif culties, and Russia’s

decision to halt gas deliveries to several European

countries. The prices of several nonfuel commodities

that are vital inputs to some manufacturing industries

jumped in the early days of the con ict, including

neon gas (an input in semiconductor chip production),

palladium (an input in semiconductors and catalytic

converters), nickel (an input in electric vehicles’

batteries), and platinum. However, prices have

since retreated to near pre-invasion levels as major

disruptions have failed to materialize thus far. Finally,

blocked shipping routes in the Black Sea have severed

the region’s agricultural exports, disrupting global food

markets. As a result, prices of corn, wheat, sun ower

oil, and fertilizer have climbed to record-high levels,

raising concerns of food insecurity across the globe.

Further aggravating the situation, a number of countries

introduced export bans on some food commodities to

contain rising domestic food prices.

Thus far, the war appears to have had more limited

effects on other aspects of global supply chains.

The effect on supplier delivery times across Europe

has been muted, suggesting that the repercussions

for manufacturers in the region have been relatively

modest so far outside of the shifts in commodity prices

Developments in Global Supply Chains (continued)

Euro area

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

Diusion index

2022202120202019

G. Purchasing managers index: Supplier delivery times

Monthly

United Kingdom

N

OTE: The series are seasonally adjusted. Values greater than 50

indicate

that more respondents reported longer delivery times relative

to

a month earlier than reported shorter delivery times.

SOURCE: For the United Kingdom, S&P Global and the

Chartered

Institute of Procurement & Supply; for the euro area, S&P Global; all via

Haver Analytics.

( gure G). The global transportation system has also

proved mostly resilient to the war, with signs of further

strain in only a couple of sectors. Oil tanker charter

rates spiked, boosted by a rise in demand as oil started

to move to new markets, while truck transportation

prices rose further, re ecting higher diesel fuel costs.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 11

5to 10years rose to 3.3percent in the June

preliminary reading. If conrmed, this reading

would be near the top of the range from the

past 25years. Nevertheless, it remains well

below the corresponding measure of 1-year-

ahead ination expectations. In the second-

quarter Survey of Professional Forecasters, the

median expectation for 10-year PCE ination

edged up to 2.4percent, reecting noticeable

upward revisions to expected ination this

year and next but little change thereafter; the

median expectation for 6 to 10years ahead

held steady at 2percent.

Market-based measures of longer-term

ination compensation, which are based

on nancial instruments linked to ination,

are sending a similar message. A measure

of consumer price index (CPI) ination

compensation 5 to 10years ahead implied

by Treasury Ination-Protected Securities is

little changed (on balance) since late 2021 and

remains well below the corresponding measure

of ination compensation over the next 5years

(gure7).

The Index of Common Ination Expectations,

which is produced by Federal Reserve Board

sta and synthesizes information from a large

range of near-term as well as longer-term

expectation measures, edged up in the rst half

of this year and now stands at the high end of

the range from the past 20years.

The labor market continued to tighten

Payroll employment expanded an average of

488,000 per month in the rst ve months of

the year (gure8). Payroll gains so far this year

have been broad based across industries, with

the leisure and hospitality sector continuing to

see the largest gains as people continued their

return to activities that had been cut back by

the pandemic.

The increase in payrolls was accompanied

by further declines in the unemployment

rate, which fell 0.3percentage point over the

rst ve months of the year to 3.6percent

in May, just above the bottom of its range

125

130

135

140

145

150

155

Millions of jobs

202220202018201620142012201020082006

8. Nonfarm payroll employment

Monthly

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

5-year

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Percent

2022202020182016201420122010

7. Ination compensation implied by Treasury

Ination-Protected Securities

Daily

5-to-10-year

N

OTE: The data are at a business-day frequency and are estimated

from smoothed nominal and ination-indexed Treasury yield curves.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Federal Reserve Board

sta calculations.

12 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

over the past 50years (gure9). The

decline in the unemployment rate has been

fairly broad based across age, educational

attainment, gender, and ethnic and racial

groups (gure10). These declines have

helped employment of nearly all major

demographic groups recover to near or above

their levels before the pandemic. (See the box

“Developments in Employment and Earnings

across Groups.”)

While labor demand remained very

strong, labor supply increased only

modestly and stayed below

pre-pandemic levels

Demand for labor continued to be very

strong in the rst half of the year. At the

end of April, there were 11.4million job

openings—60percent above pre-pandemic

levels and down a bit from the all-time high

recorded in March.

Meanwhile, the supply of labor rose only

gradually and remained below pre-pandemic

levels. The labor force participation rate

(LFPR), which measures the share of people

Black or African American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Percent

202220202018201620142012201020082006

10. Unemployment rate, by race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. Persons whose ethnicity is identied as Hispanic or Latino

may be of any race. Small sample sizes preclude reliable estimates for Native Americans and other groups for which monthly data are not reported by

the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Percent

202220202018201620142012201020082006

9. Civilian unemployment rate

Monthly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 13

either working or actively seeking work,

edged up just 0.1percentage point in the

rst ve months of the year—following a

0.4percentage point improvement last year—

to 62.3percent in May (gure11).

2

Despite these improvements, the LFPR

remains 1.1percentage points below its

February2020 level.

3

About one-half of

this decline in the participation rate was

to be expected even in the absence of the

pandemic, as additional members of the

large baby-boom generation have reached

retirement age. In addition, several pandemic-

related factors appear to be continuing to

hold down the participation rate, including

a pandemic-induced surge in retirements

(beyond that implied by the aging of the

baby boomers) and, to a diminishing extent,

increased caregiving responsibilities and

some continuing concerns about contracting

COVID-19.

In addition to subdued participation, a second

factor constraining the size of the labor force

has been a marked slowing in population

growth since the start of the pandemic. Over

2020 and 2021, the working-age (16 and over)

population grew by 0.4percent per year on

average—notably less than the 0.9percent

2. The Bureau of Labor Statistics incorporated new

population estimates beginning with the January2022

employment report. This development resulted in a

one-time jump in the estimate of the aggregate LFPR

of about 0.3percentage point due to a change in the

age distribution of the population. Accordingly, the

0.4percentage point increase in the published measure

from December to May overstates the improvement in

the LFPR by about 0.3percentage point.

3. This shortfall in the LFPR corresponds to

a shortfall in the labor force of about 2.8million

persons. (This calculation holds the LFPR constant

at its February2020 level and assumes population

growth equal to the actual growth observed since

February2020.)

Employment-to-

population ratio

50

52

54

56

58

60

62

64

66

68

Percent

202220202018201620142012201020082006

11. Labor force participation rate and

employment-to-population ratio

Monthly

Labor force participation rate

N

OTE: The labor force participation rate and the employment-

to-population ratio are percentages of the population aged 16 and over.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

14 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

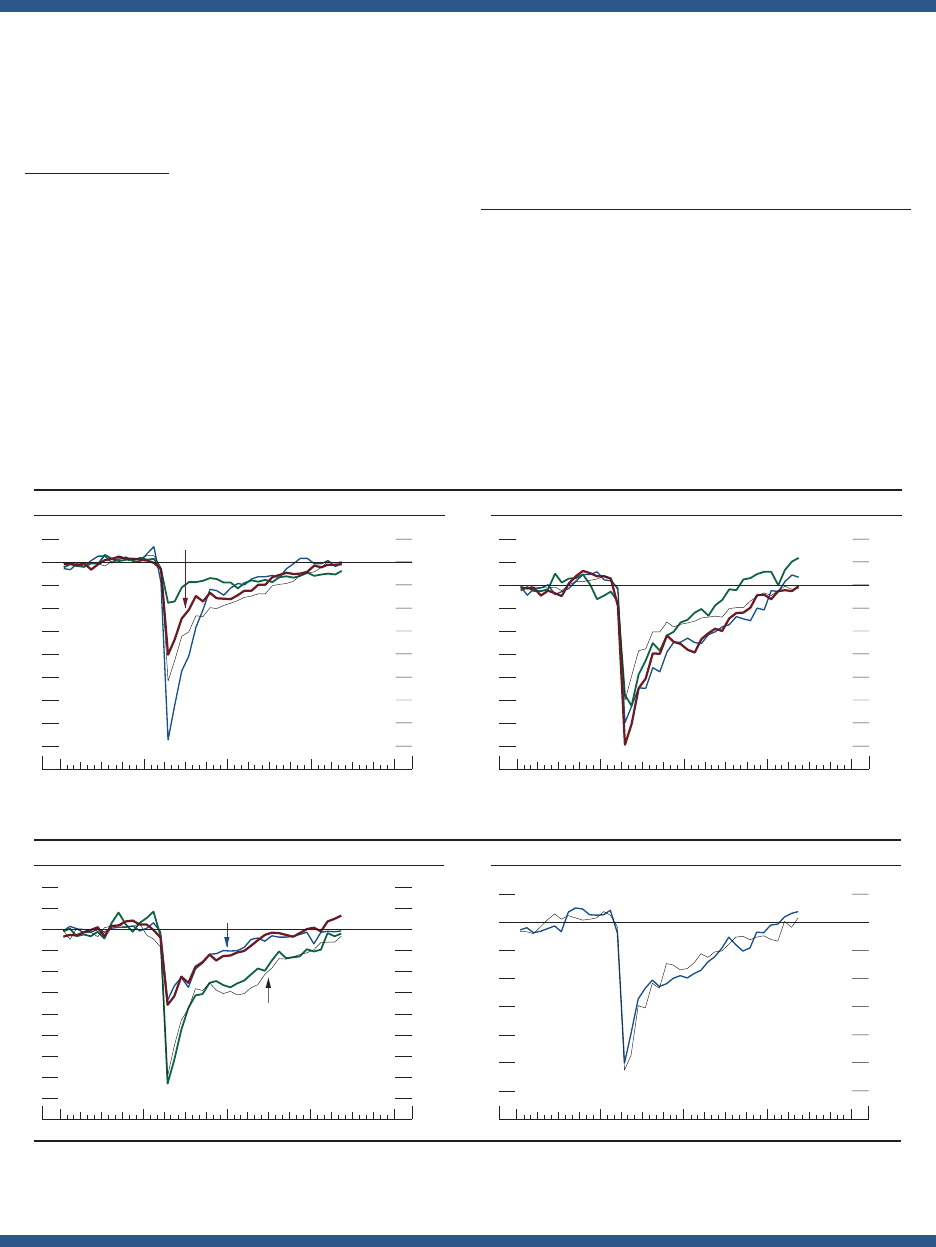

Employment for Blacks and Hispanics not only

declined by more than that for whites and Asians

early in the pandemic, but also recovered more

quickly since the end of last year ( gure A, upper-

right panel). In addition, men and women with high

school degrees or less saw larger declines and a faster

recovery ( gureA, lower-left panel). Similarly, gaps in

employment between prime-age mothers and non-

mothers that widened through 2020 have essentially

closed ( gureA, lower-right panel). By April2022,

employment for all of those groups was near or above

its pre-pandemiclevel.

These differences in the timing of the employment

recovery across different demographic groups partly

re ect the evolution of the pandemic’s effect on the

labor market. For instance, social-distancing restrictions

and concerns about contracting or spreading

COVID-19 had likely inhibited employment in in-

person services. As these restrictions and concerns

have waned, employment of groups more commonly

employed in in-person services, such as those with less

education and some minority groups, has recovered

quickly.

3

Further, the closing of many schools and

childcare facilities for the 2020–21 school year due

to elevated levels of COVID cases likely held back

the employment recovery of parents, as many families

faced uncertainties about the consistent availability

of in-person education for school-age children and

childcare for younger children. The effects appear to

have been particularly acute for mothers, especially

Black and Hispanic mothers, as well as those with less

3. Before the pandemic, Blacks and Hispanics were

less likely to be employed in jobs that could be performed

remotely, and women and Blacks were more likely to be

employed in occupations that involved greater face-to-face

interactions; for example, see Laura Montenovo, Xuan Jiang,

Felipe Lozano Rojas, Ian M. Schmutte, Kosali I. Simon,

Bruce A. Weinberg, and Coady Wing (2020), “Determinants

of Disparities in COVID-19 Job Losses,” NBER Working

Paper Series 27132 (Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of

Economic Research, May; revised June2021), https://www.

nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w27132/w27132.pdf.

Other research shows that even after accounting for

workers’ job characteristics, Hispanic and nonwhite workers

experienced a higher rate of job loss relative to other

workers; see Guido Matias Cortes and Eliza Forsythe (2021),

“The Heterogeneous Labor Market Impacts of the Covid-19

Pandemic,” unpublished paper, August, http://publish.illinois.

edu/elizaforsythe/files/2021/08/Cortes_Forsythe_Covid-demo_

revision_8_1_2021.pdf.

Labor market gains have been robust over the

past year and a half as the economy continues to

recover from the effects of the pandemic. Historically,

economic downturns have tended to exacerbate

long-standing differences in employment and earnings

across demographic groups, especially for minorities

and for those with less education, and this pattern was

especially true early on in the pandemic. However,

as pandemic-related factors have eased and the labor

market has recovered, groups with larger employment

declines early in the pandemic have had especially

large increases lately. Now employment and real

earnings of nearly all major demographic groups are

near or above their levels before the pandemic, and

employment rates are again near multidecade highs.

Different age groups have had very different

employment experiences over the course of the

pandemic.

1

Early in the pandemic, the employment-to-

population (EPOP) ratio for people aged 16 to 24 not

only declined by much more than that for people of

prime age (25 to 54) and those aged 55 to 64, but also

recovered much more quickly (see gure A, upper-

left panel).

2

Conversely, employment recovered more

slowly for prime-age people throughout 2020 and

nearly all of 2021. But in late 2021 and early 2022,

the prime-age EPOP rose quickly, such that now all

three of these age groups’ EPOP ratios have essentially

recovered to their pre-pandemic levels. The EPOP ratio

for those aged 65 and over, however, remains about

1percentage point below its pre-pandemic level—a

level it has maintained through much of the pandemic.

The lower EPOP ratio for that group is entirely

attributable to a lower labor force participation rate,

which in turn largely re ects an increase in retirements

since the onset of the pandemic.

A closer look at the prime-age group shows that

there has been considerable heterogeneity in the pace

of the employment recovery across race and ethnicity,

educational attainment, and parental status.

1. The January2022 employment report incorporates

population controls that showed that the working-age

population was both larger and younger over the past

decade than the Census Bureau had previously estimated.

Those population controls had meaningful effects on the

aggregate EPOP ratio, but much smaller effects at the levels of

disaggregation examined in this discussion.

2. This discussion de nes the pre-pandemic baseline

EPOP ratio for each group as that group’s average EPOP ratio

over 2019.

Developments in Employment and Earnings across Groups

(continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 15

year, these childcare burdens likely eased, allowing

many parents to reenter the workforce.

See Joshua Montes, Christopher Smith, and Isabel Leigh

(2021), “Caregiving for Children and Parental Labor Force

Participation during the Pandemic,” FEDS Notes (Washington:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

November5), https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/

feds-notes/caregiving-for-children-and-parental-labor-force-

participation-during-the-pandemic-20211105.htm.

A. Changes in employment-to-population ratio compared with the 2019 average ratio, by group

16 to 24

Black or

African American

65+

Asian

55 to 64

Hispanic or Latino

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

+

_

0

2

Percentage points

2022202120202019

Age group

Monthly

25 to 54

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

+

_

0

2

4

Percentage points

2022202120202019

Race and ethnicity: Prime age

Monthly

White

Men, college

or more

Parents

Women, high school

or less

Women, college

or more

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

+

_

0

2

4

Percentage points

2022202120202019

Educational attainment: Prime age

Monthly

Men, high school

or less

N

OTE

: Prime age is 25 to 54. The age groups 16 to 24 and prime age show seasonally adjusted data published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, whereas

all other groups’ data are seasonally adjusted by the Federal Reserve Board sta.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations from Current Population Survey microdata.

12

10

8

6

4

2

+

_

0

2

Percentage points

2022202120202019

Parental status: Prime-age women

Monthly

Nonparents

(continued on next page)

education.

4

However, with schools having generally

provided in-person education for the 2021–22 school

4. The increase in the share of mothers of school-age

children who reported being out of the labor force due to

caregiving closely tracked the degree to which schools were

fully closed to in-person learning over the 2020–21 school

year, and districts that serve more Blacks and Hispanics

were less likely to provide fully in-person education during

the 2020–21 school year, which may account for some

of the larger and more persistent declines in labor force

attachmentfor Black and Hispanic mothers over this period.

16 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

time real earnings for women versus men is slightly

smaller in 2022:Q1 than it was in 2019, as is the gap

in median real earnings between Black and white full-

time workers.

6

6. Some of a group’s earnings growth relative to 2019 may

re ect lingering pandemic-related compositional shifts in the

group’s full-time workers. Additionally, real earnings growth

accounts for aggregate in ation, but some demographic

groups may be disproportionately exposed to in ation due

to differences in groups’ consumption patterns—implying

lower real earnings growth for groups with greater exposure to

in ation.

Although the gaps in employment outcomes

across groups that widened during the pandemic have

diminished, the considerable gaps that existed before

the pandemic remain. For example, the EPOP ratio for

whites of prime age remains more than 3percentage

points above those for prime-age Black and Hispanic

people; the EPOP ratio of college-educated, prime-age

people is about 15percentage points higher than that

of prime-age people with high school degrees or less;

and the EPOP ratio for prime-age mothers is about

5percentage points below that of non-mothers—all

similar in size to the gaps that existed before the

pandemic.

The broad-based nature of the labor market recovery

is also apparent in workers’ earnings, which have

grown rapidly as employment surged in 2021 and early

2022. As of 2022:Q1, the median full-time worker’s

usual weekly earnings had grown 12.3percent relative

to pre-pandemic levels—implying real earnings growth

of 3.1percent ( gure B).

5

Although this earnings growth

has been widespread, it has been largest for women,

minorities, young workers, and workers with less than a

high school education. The growth in earnings for some

demographic groups has been suf ciently robust to

shrink some pre-pandemic disparities in real earnings

between groups. For instance, the gap in median full-

5. Just as with the change in the EPOP ratio, each group’s

pre-pandemic baseline is de ned as the group’s average

median usual weekly earnings in 2019. The reported growth in

real usual weekly earnings de ates nominal earnings growth

by total PCE (personal consumption expenditures) in ation.

If, instead, the CPI were used to de ate nominal earnings,

then reported real earnings growth since 2019 would be

2percentage points lower—but even when using the CPI to

de ate nominal earnings, real earnings have risen for most

groups since 2019.

B. Growth in median full-time usual weekly earnings

from 2019 to 2022:Q1

Percent change relative to 2019 average

NominalReal (PCE)

0246810121416

Hispanic or Latino

Asian

Black or African American

White

65+

55–64

25–54

16–24

Bachelor’s or more

Some college

High school

Less than high school

Women

Men

Overall

N

OTE: The percent change as of 2022:Q1 is relative to the 2019 average of

the

median usual weekly earnings for full-time workers in each group. Real

earnings growth deates the nominal earnings growth by the average growth in

the

personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index as of 2022:Q1

relative

to its 2019 average level. The overall earnings, as well as those for men

and

women, use seasonally adjusted data, but the other groups’ earnings are

not seasonally adjusted. The key identies bars in order from left to right.

S

OURCE

: For median usual weekly earnings, Bureau of Labor Statistics; for

the PCE price index, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Developments in Employment and Earnings across Groups (continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 17

average rate over the previous ve years.

4

The slowing in population growth over

2020–21 was due to both a sharp decline in

net immigration and a spike in COVID-related

deaths.

5

Had the population increased over

2020–21 at the same rate as over the previous

ve years, the labor force would have been

about 1¾million larger as of the second

quarter of this year.

6

As a result, labor markets remained

extremely tight . . .

Reecting very strong demand for workers

alongside still-subdued supply, a wide range

of indicators have continued to point to an

extremely tight labor market despite the fact

that the level of payroll employment in May

remained about 820,000 below the level in

February2020.

7

The number of total available

jobs, measured by total employment plus

posted job openings, continued to far exceed

the number of available workers, measured by

the size of the labor force.

8

The gap was

4. Population forecasts just before the onset of the

pandemic also projected faster population growth

for 2021–22 than has been realized. For example, the

Congressional Budget Oce projected 0.8percent

growth per year in 2021–22 in its January2020 budget

and economic projections; see Congressional Budget

Oce (2020), The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2020

to 2030 (Washington: CBO, January), https://www.cbo.

gov/publication/56020. Before 2015, population growth

was even higher. For example, the average growth rate in

the working-age population between 1980 and 2014 was

1.2percent per year.

5. The eect of COVID-related deaths on the labor

force, however, was relatively smaller, because these

deaths have been concentrated among older individuals,

who tend to have low LFPRs.

6. This calculation uses the actual LFPR in May2022

and multiplies it by the level of the population that would

have been realized in that month had population growth

over 2020–21 been the same as the growth observed over

2015–19.

7. After adjusting for population growth since the

beginning of the pandemic, the shortfall in payrolls

relative to their pre-pandemic level was about 2.3million

in May.

8. The labor force includes all people aged 16

and older who are classied as either employed or

unemployed.

18 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

about 5½million at the end of April, near the

highest level on record.

9

The share of workers

quitting jobs each month, an indicator of the

availability of attractive job prospects, was

2.9percent at the end of April, near the all-

time high reported in November (gure12).

Initial claims for unemployment benets

remain near the lowest levels observed in

the past 50years. Households’ and small

businesses’ perceptions of labor market

tightness were near or above the highest

levels observed in the history of these series.

And, nally, employers continued to report

widespread hiring diculties.

That said, some possible signs of modest

easing of labor market tightness have recently

appeared. For example, as noted in the next

section, some measures of wage growth appear

to have moderated. And in the June2022 Beige

Book, employers in some Federal Reserve

Districts reported some signs of modest

improvement in worker availability.

. . . and nominal wages continued to

increase at a robust pace

Reecting very tight labor market conditions,

nominal wages continued to rise at historically

rapid rates. For example, the employment

cost index (ECI) of total compensation rose

4.8percent over the 12 months ending in

March, well above 2.8percent from a year

earlier (gure13). The most recent readings

include a surge in bonuses, which may reect

the challenges of retaining and hiring workers.

In addition, wage growth as computed by

the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, which

tracks the median 12-month wage growth

of individuals responding to the Current

Population Survey, picked up markedly this

year and rose more than 6percent in May, well

above the 3to 4percent pace reported over the

previous few years.

9. Another usual indicator of the gap between

available jobs and available workers is the ratio of job

openings to unemployment. At the end of April, this

indicator showed that there were 1.9 job openings per

unemployed person.

Compensation per hour,

business sector

Atlanta Fed’s

Wage Growth Tracker

Employment cost index,

private sector

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

10

Percent change from year earlier

20222020201820162014

13. Measures of change in hourly compensation

Average hourly earnings,

private sector

N

OTE: Business-sector compensation is on a 4-quarter percent change

basis. For the private-sector employment cost index, change is over the

12 months ending in the last month of each quarter; for private-sector

average hourly earnings, the data are 12-month percent changes; for the

Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker, the data are shown as a 3-month

moving average of the 12-month percent change.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta,

Wage Growth Tracker; all via Haver Analytics.

Vacancy-to-

unemployment ratio

0

.3

.6

.9

1.2

1.5

1.8

2.1

2.4

Ratio

.8

1.2

1.6

2.0

2.4

2.8

3.2

202220202018201620142012201020082006

12. Ratio of job openings to job seekers and quits rate

Percent of employment

Nonfarm quits rate

N

OTE: The data are monthly and extend through April 2022. The

vacancy-to-unemployment ratio data are the ratio of job openings to

unemployed.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor

Turnover Survey.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 19

That said, there are some signs that

nominal wage growth may be leveling o or

moderating. The growth of wages and salaries

as measured by the ECI moderated from

5.6percent at an annual rate in the second half

of last year to 5.2percent early this year. And

even as payroll employment continued to grow

rapidly and the unemployment rate continued

to fall, the three-month change in average

hourly earnings declined from about 6percent

at an annual rate late last year to 4.5percent

in May, with the moderation in earnings

growth particularly notable for employees in

the sectors that experienced especially strong

wage growth last year, such as leisure and

hospitality.

Following a period of solid growth, labor

productivity softened

The extent to which sizable wage gains

raise rms’ unit costs and act as a source of

ination pressure depends importantly on the

pace of productivity growth. Considerable

uncertainty remains around the ultimate

eects of the pandemic on productivity.

From 2019 through 2021, productivity growth

in the business sector picked up (albeit by

less than compensation growth), averaging

about 2¼percent at an annual rate—about

1percentage point faster than the average pace

of growth over the previous decade (gure14).

Some of this pickup in productivity growth

might reect persistent factors. For example,

the pandemic resulted in a high rate of new

business formation, the widespread adoption

of remote work technology, and a wave of

labor-saving investments.

The latest reading, however, showed a

decline in business-sector productivity in the

rst quarter of this year. While quarterly

productivity data are notoriously volatile, this

decline nevertheless highlights the possibility

that some of the earlier productivity gains

could prove transitory, perhaps reecting

worker eort initially surging in response to

employment shortages and hiring diculties

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

Percent, annual rate

14. Change in business-sector output per hour

1949–

73

1974–

95

1996–

2003

2004–

08

2009–

18

2019–

21

2022

N

OTE

: Changes are measured from Q4 of the year

immediately

preceding the period through Q4 of the nal year of the period, except

2022 changes, which are calculated from 2021:Q1 to 2022:Q1.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

20 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

and then subsequently returning to more

normal levels.

10

If the gap between wage

growth and productivity growth remains

comparably wide in the future, the result

will be signicant upward pressure on rms’

laborcosts.

Gross domestic product declined in the

rst quarter of 2022 after having surged

in the fourth quarter of 2021 . . .

Real gross domestic product (GDP) is reported

to have surged at a 6.9percent annual rate in

the fourth quarter of 2021—and then to have

declined at a 1.5percent annual rate in the rst

quarter—because of uctuations in net exports

and inventory investment (gure15). These

two categories of expenditures are volatile even

in normal times, and they have been even more

so in recent quarters. Some improvement in

supply chain conditions late last year appears

to have enabled rms to rebuild depleted

inventories; inventory investment surged in

the fourth quarter and then moderated to a

still-elevated pace in the rst quarter, thereby

weighing on GDP growth. Other measures

of activity, including employment, industrial

production, and gross domestic income,

indicate continued growth in the rst quarter.

. . . while growth in consumer spending

and business investment was solid in the

rst quarter

After abstracting from these volatile

components, growth in private domestic nal

demand (consumer spending plus residential

and business xed investment—a measure

that tends to be more stable and better reects

the strength of overall economic activity)

was solid in the rst quarter, supported by

some unwinding of supply bottlenecks and a

further reopening of the economy. The most

recent spending data and other indicators

suggest that private xed investment may be

10. The November2021 Beige Book reported that

many employers were planning to increase hiring because

of concerns that their current workforce was being

overworked.

17.0

17.5

18.0

18.5

19.0

19.5

20.0

Trillions of chained 2012 dollars

20222021202020192018201720162015

15. Real gross domestic product

Quarterly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JUNE 2022 21

moderating, but consumer spending remains

strong and drag from inventory investment

and net exports may be dissipating. As a

result, private domestic nal demand and real

GDP appear on track to rise moderately in the

second quarter.

Real consumer spending growth

remained strong . . .

Real consumer spending—that is, spending

after adjusting for ination—continued to

grow briskly, supported by a partial unwinding

of supply bottlenecks and continued

normalization of spending patterns as the

pandemic fades. For example, spending

on motor vehicles grew markedly in the

rst quarter, reecting improvements in

both domestic and foreign production, and

spending on services (especially at restaurants)

grew briskly.

That said, consumer spending growth has

moderated from its very rapid pace from

early 2021 as scal support has declined

from historical highs, some households have

likely depleted excess savings accumulated

during the pandemic, and ination has eroded

households’ purchasing power.

The composition of spending remains more

tilted toward goods and away from services

than it was before the pandemic. Real goods

spending is still well above its trend, while

real spending on services remains below trend

(gure16). Nevertheless, the composition

continued to shift back toward services. While

goods spending was only modestly higher in

April compared with its average from late last

year, services spending rose signicantly.

. . . supported by high levels of wealth

Household wealth grew by roughly $30trillion

between late 2019 and late 2021 because of

rises in equity and house prices along with

the elevated rate of saving in 2020 and 2021

(gures17 and 18). Since the beginning of the

year, wealth has declined because of the drop

in equity prices. Nevertheless, wealth remains

0

4

8

12

16

20

24

28

32

36

PercentMonthly

202220202018201620142012201020082006

18. Personal saving rate

NOTE: The data extend through April 2022.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Goods

6.5

7.0

7.5

8.0

8.5

9.0

9.5

Trillions of chained 2012 dollars

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

202220202018201620142012201020082006

16. Real personal consumption expenditures

Trillions of chained 2012 dollars

Services

N

OTE: The data are monthly and extend through April 2022.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

7.5

8.0

8.5

Ratio

202220202018201620142012201020082006

17. Wealth-to-income ratio

Quarterly

NOTE: The series is the ratio of household net worth to disposable

personal income.

S

OURCE: For net worth, Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release