MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

1

Retention framework for

research data and records

1 Background and scope

You may be asked to make decisions about the retention of research data and related material

(e.g. laboratory notebooks, biological samples, images, microscope slides, home office licences

and other regulatory or ethical approvals, questionnaires, participant information sheets,

consent forms, etc.).

This framework provides guidance on:

• how to make risk proportionate decisions about the retention or potential destruction of

research data and related material

• the importance of documenting, and keeping a record of, any decisions relating to the

retention (or destruction), of research data and related material; and

• where you can access further guidance to make these decisions with appropriate support.

This framework is designed primarily for UKRI employed staff (e.g. staff in MRC Institutes)

and for those whose clinical research is sponsored by UKRI. It is not designed for researchers

to make decisions about the retention or destruction of research data on their own; but rather

for decisions to be made in partnership, with the involvement of other relevant parties.

Preservation of research data is important for a number of reasons:

• it supports Open Science and promotes reproducibility (important for transparency);

• it provides an audit trail or an archive of the research run in your Institute (this may include

permanent preservation of research which is historically significant or important);

• it enables future research opportunities through data or sample sharing.

However, the retention of research data (including any sample storage / biobanking) and long-

term archiving, does not come without financial cost. It’s therefore important to weigh up the

risks of retaining research data versus the risks of its destruction before taking well-informed,

risk proportionate decisions about what to keep. Efforts can then focus on managing retention

for research which poses ‘high risk’ and taking a light touch approach for all other research.

Examples of research posing ‘high risk’ might include:

• Research studies where there is a greater likelihood that scientists will be asked to provide

data and/or samples, to support further research or to enable reproduction of findings as

these are high profile / high impact or in some way contentious; or

• Research which has generated Intellectual Property (IP), or where there is potential IP; or

• Research studies where there is a greater likelihood that participants might suffer harm as

a result of the research.

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

2

1.1 MRC Policy

MRC’s Retention Policy for research data and related material is outlined in Good Research

Practice: Principles and Guidelines. Good Research Practice (GRP) is intended to complement

statutory or regulatory requirements (e.g. Clinical Trials Regulations, data protection law,

1

etc.).

The retention periods in GRP apply to research data and related material in MRC Institutes

where MRC / UKRI is your employer or the sponsor of your research. If you are based in MRC

Head Office or in an MRC institute there is additional guidance on managing business

information (i.e. non-research records) in the UKRI Information Management Policy and UKRI

Retention Schedule. You can also seek guidance from the UKRI Knowledge and Information

Management Team.

For MRC funded research, GRP is advisory although it can be used to inform local policy.

Where MRC is purely your funder, local organisational policy and/or your sponsor(s) policies on

retention will apply (e.g. if you do clinical research in a university, then your university and/or

sponsor(s) guidance on retention should be followed).

For MRC university units and centres (where MRC used to be the employer) GRP applies to

research data and related materials generated when MRC was your employer. (Any retention

commitments may be outlined in the Unit closure or Unit transfer agreement). For research data

and related material generated after transition, local university and/or sponsors’ policies apply.

MRC also provide information on Open Research and Data Management and Sharing.

Minimum retention periods for research data and related material where UKRI is your

sponsor and/or employer

For basic research – at least 10 years after the study has been completed.

For population health and clinical studies – at least 20 years after study completion.

Studies which propose retention periods beyond the minimum limits stated above, must include

valid justification. However, it may be appropriate to consider longer retention periods in some

cases; for example, where there is:

• a greater likelihood that scientists will be asked to share data with others for further

research or for reproducibility reasons (i.e. because their research findings are high

profile/high impact or in some way contentious);

• Intellectual Property or the potential for IP to arise (e.g. laboratory notebooks and/or

relevant records from clinical studies could be retained indefinitely);

• a greater likelihood that participants might suffer harm as a result of the research. For

example, a clinical drug trial involving pregnancy (i.e. the clinical trial actively recruited

pregnant mothers or a participant / their partner became pregnant during the trial), then a

retention period of 25 years might be more sensible to cover any potential claim for

1

In terms of primary data protection law, researchers can keep data indefinitely for research (subject to

appropriate ‘safeguards’). If research data are no longer useful, or unlikely to be used in further research, then

you should consider their destruction.

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

3

damages that may arise from either the participant or their child). For those who lack

capacity to consent, a claim could arise at any time. Therefore, it would seem sensible to

review what is being kept at 20-25 years to determine whether to keep records longer.

• a direct impact on national policy making and/or the results are of historical importance

(e.g. the MRC have permanently preserved proposals relating to the Human Genome

Mapping Project in The National Archives).

1.2 Active management

There should be a clear and transparent system in place to manage research data and

samples.

• There should be an identified person, or persons, responsible for managing all research

data and/or samples (e.g. the Principal Investigator or Trial Steering Committee, or a

librarian, Information / Data Manager, Designated Individual or equivalent).

• There should be a register, database or inventory to manage research samples and/or

data. For example the UKRI Information Asset Register tracks relevant information on key

UKRI datasets such as storage location, time of data collection, type of data and any

decisions with respect to destruction.

• It should be easy for those authorised to access data and/or samples, to be able find and

access what they need (i.e. via meta-data or data documentation for electronic format or

an inventory or database for samples or other physical records). This is particularly

important for sample and data sharing.

1.3 Organisational policies

In order for organisations to carry out their responsibilities, under data protection law as well as

research governance responsibilities

2

, all will have their own policies on data / records retention.

(We discussed MRC’s policy at 1.1).

1.4 Expectations of other organisations

Similarly, funders, journals and others may have their own requirements. You will need to

understand and meet the policies of all of the relevant organisation(s) involved in your research

(e.g. those providing regulatory oversight, your collaborators, funders or journals) and consider

how these expectations will impact research data and/or sample retention. (In some cases

these expectations may be outlined in an agreement).

For example, any organisation providing regulatory oversight may either audit and/or inspect

your premises (e.g. Health & Safety Executive, Home Office, Human Tissue Authority,

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, etc.). You should be aware of the

research data and/or samples that they are likely to want to see and ensure that you can

provide access to these.

2

These are outlined in the UK policy framework for health and social care research. In addition the Medicines for

Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations outline requirements for Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal

Products.

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

4

If your research involves external collaboration with the NHS, they will have their own

expectations and may check compliance. You should be aware of these expectations, be

confident that you are in a position to deliver them and consider any long-term requirements

(i.e. how long do they expect you to retain any research data and/or samples and who should

pay for storage?).

2 Deciding what, how and where to keep

2.1 What to keep?

During the lifecycle of any research project a whole range of data and/or samples will be

generated, recorded, collected or used. What to keep will very much depend upon your

research and what you need in order to enable an understanding of what was done when, how

and why. This process should be led by someone who is familiar with the research (e.g. the

Principal Investigator or Trial Steering Committee) with decisions about retention being made in

line with organisational policy and sponsor(s) expectations (where appropriate).

For some basic research the information recorded in laboratory notebooks may provide

sufficient detail to enable an understanding of what was done when, how and why. Whilst for

some clinical studies a whole raft of data / records will be required in order to enable that

same understanding.

Decisions about what to keep need to be made on a case-by-case basis with respect to which

data and/or samples are required in order to meet the aims of data preservation (e.g. to support

open science and reproducibility of findings, to provide an audit trail and to enable data

sharing). Where appropriate any decisions must be in line with the expectations of participants;

i.e. if a participant were to withdraw consent from your study, then you would retain their data

and/or samples in line with what was agreed with respect to their withdrawal (e.g. the participant

may have agreed that you can retain what you already hold, but that you won’t accrue any

further data and/or samples).

A risk proportionate approach should be taken to decisions about retention and any long-term

archiving. There should be some form of risk assessment for all studies to determine those

which are ‘high risk’ and require additional management. For example, you may decide to

manage ‘high risk’ studies by retaining data and/or samples for longer in their original format.

That’s not to say that all research data from ‘high risk’ studies (or indeed any study) should be

kept for longer and/or in their original form as the scenarios below demonstrate:

What to keep – scenario 1

For some basic research any decision-making about what to keep may be influenced by the

outcome of the research. A record of what was done when, how and why will always be kept in

laboratory notebooks. If an experiment didn’t work (rather than produced negative results) then

the original output may not be as valuable to preserve and may not necessarily be kept

(although a record of this decision should be clearly documented, signed off and retained for

future reference so that you can track the fate of the original output). You may also consider

retention of original outputs in the short term for protocol optimisation reasons.

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

5

Some original outputs take up a lot of physical space (e.g. plates and cell cultures). Normally

plates are captured via a plate reader and the images printed and/or saved electronically.

Keeping a cell culture may also be less important if the initial biological starting material and/or

any resulting cell line is preserved. As such cell cultures and plates would usually only be kept if

deemed useful and/or unlikely to deteriorate.

What to keep – scenario 2

Some outputs can deteriorate over time. Gels and immuno blots are normally photographed and

then discarded as they are too fragile to maintain. Stained microscope slides may be retained

after analysis but may not be worth keeping in the long-term as the staining can fade over time

(and slides can take up a lot of physical space).

What to keep – scenario 3

It’s worth considering whether keeping a physical paper record is necessary in the longer term.

If you were to recruit healthy volunteers to a volunteer database, you might ask them to

complete a paper form to capture some personal details (i.e. name, address, contact telephone

number) as well as the types of research in which they might like to take part. All of these

details could then be entered into a database and the original form stored for reference.

Is it worth keeping these original paper forms in the longer term? The information that you need

is now stored in the database. Therefore, as long as there is some form of quality assurance

process to ensure that the data in the database is accurate and valid, then the original paper

forms can be destroyed after an agreed period of time. Your quality assurance process should

be clearly documented, signed off, and retained for future reference (this should include details

about the destruction of the original paper forms). It’s important to document the decision to

destroy these forms and retain a copy of this decision for future reference. You can then

accurately demonstrate what has been destroyed and track the fate of all your research data

and/or samples.

It’s also worth considering the risk of keeping the original paper forms in the longer term and

balancing this against the risk of destruction. The forms contain ‘personal data’ and are

therefore subject to data protection law and confidentiality requirements. Storing the original

paper forms in the longer term, particularly if this will mean storing them with an external

archiving organisation, presents a potential risk to your volunteers’ privacy as well as a cost

burden.

2.2 What format - Physical versus electronic?

Scenario 3 can be applied more generally as any research data may be collected in physical

form (i.e. biological samples, microscope slides, on paper, etc.) and/or in electronic form. Where

both a physical and electronic copy of the same data exists, decisions can be made with

respect to whether to keep both formats in the longer term or not. These decisions should be

made by someone who is familiar with the research data (e.g. the Principal Investigator or Trial

Steering Committee) in line with organisational policy and sponsor expectations (where

appropriate).

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

6

Good Research Practice: Principles and Guidelines allows for the conversion of original paper

records into electronic format (e.g. by inputting data into software or by scanning). In principle,

both of these options can be a good solution to reducing long-term paper archiving costs.

However, neither comes without cost, both are time consuming and there is the potential for

error as explored in the following scenario.

Scanning scenario: An MRC Unit wanted to stop retaining the original paper copies of a

screening form and consent form for people undergoing an MRI scan, and switch to electronic

scanned copies. In line with Good Research Practice, as long as there is a system in place

which serves to check that the screening forms and consent forms have been scanned to an

appropriate standard, are held electronically and that this process has been signed off and

documented, then it would demonstrate that the data were: "… validated using quality

assurance procedures" and therefore destruction of the paper copies could be justified. (The

Unit also recorded the decision to destroy the paper forms, and retained this for future

reference, so they could track the fate of these forms).

It's about balancing risk:

• how likely is it that you will need to provide these forms to someone in the future (for

whatever reason – it could be for an audit, a complaint, etc.)?

It is more likely that you will be asked to provide these forms for research considered ‘high

risk’ (i.e. for research, which is high profile, high impact or in some way contentious; or

where there is a greater likelihood that participants might suffer harm).

• if you had to provide these forms would this be easier to do in paper or electronic format?

• what are the risks of retaining paper records versus electronic format? Paper can take up

more physical space than its electronic counterpart. Whilst the potential for things to be

destroyed (e.g. fire, flood) or go missing / be accidently deleted are probably fairly similar

in each case, with electronic format there is the option to make a back-up copy.

However, it’s important to note that storing electronic records is not without cost (e.g. in

terms of scanning time, server space, etc.). Electronic records also need active

management to ensure they remain accessible over time (i.e. maintaining audit trails /

keeping track of back-ups, ensuring security of back-ups, and regularly checking that files

can continue to be accessed and read as software and hardware technology advances,

etc.).

• what are the risks of transferring paper records to electronic format – again, this is where a

process of checking or validation is absolutely vital (it's no use archiving scanned records

if they haven't scanned as intended and you've got incomplete copies).

There is also the possibility for scanned records to be amended (either deliberately or

accidently). Therefore, access to these should be controlled by an appropriate person.

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

7

2.3 Where to keep?

Initially research data and/or samples will be collected and retained under the supervision of the

Principal Investigator or Trial Steering Committee (i.e. in the Principal Investigator’s employing

organisation, Clinical Trials Unit(s) and/or at any other site(s) also involved in the research).

At some point a decision may be taken to curate the data and/or samples centrally; if so, your

organisation should have a policy or process on when they should be curated centrally and

where.

Storage of biological samples: Existing collections of samples often have significant value for

research. To ensure this potential is maximised, samples can be transferred to a central tissue

resource or ‘biobank’, to maintain quality and optimise sample use. In England, Wales and

Northern Ireland research ‘biobanks’ are subject to the Human Tissue Authority’s licensing

scheme, overseen by a Designated Individual (or equivalent for unlicensed premises). The

Designated Individual is a key contact for sample management.

Samples are often only as valuable as any accompanying data; the following paragraph is

relevant where any accompanying data is identifiable.

Archiving identifiable information: In multi-site studies, participants’ identifiable information

will usually remain at the site at which they were recruited and/or treated. Although, some

identifiers may be shared with the coordinating centre (or biobank) to ensure future linkage or

for participant follow-up. Whatever the arrangements are for a specific study, participants should

be informed (and agree) to how their identifiable information will be used for research.

Completed consent forms contain identifiable information and as such are likely to be kept at

each local site. Sites may incur archiving costs as a consequence of storing such

documentation. These costs should be identified early and arrangements made as to how they

will be covered.

When archiving identifiable information away from the controlled environment in which they

were originally collected and collated, the Principal Investigator or the Trial Steering Committee

should consider any additional risk. With guidance from the sponsor and relevant Data

Protection Officer(s), Principal Investigator(s) or the Trial Steering Committee should ensure

that only the identifiable information that needs to be kept is kept (i.e. a risk-based decision) and

that data security can be maintained.

All data: Wherever research data are kept, their security must be ensured and they must be

maintained / stored in such a way that they can be easily identified and located to support future

activities (including access for audit purposes, data sharing, etc.). If you are considering storing

research data with an external service provider, you must ensure that they can do this.

If you would like further guidance on approved providers of external archiving, please contact

the UKRI Knowledge and Information Management Team.

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

8

2.4 Reviewing what you keep

Long-term storage should not be the end of the story, your organisation should have a policy /

process for reviewing what is kept with a view to either further retention or destruction of

research data or samples as appropriate. Research data or samples should only be kept for as

long as they are useful (e.g. to support further research, to defend any scientific challenge for

research which is high profile / high impact or in some way contentious, to investigate any

instances of participant harm, etc.). If research data or samples are no longer useful, you should

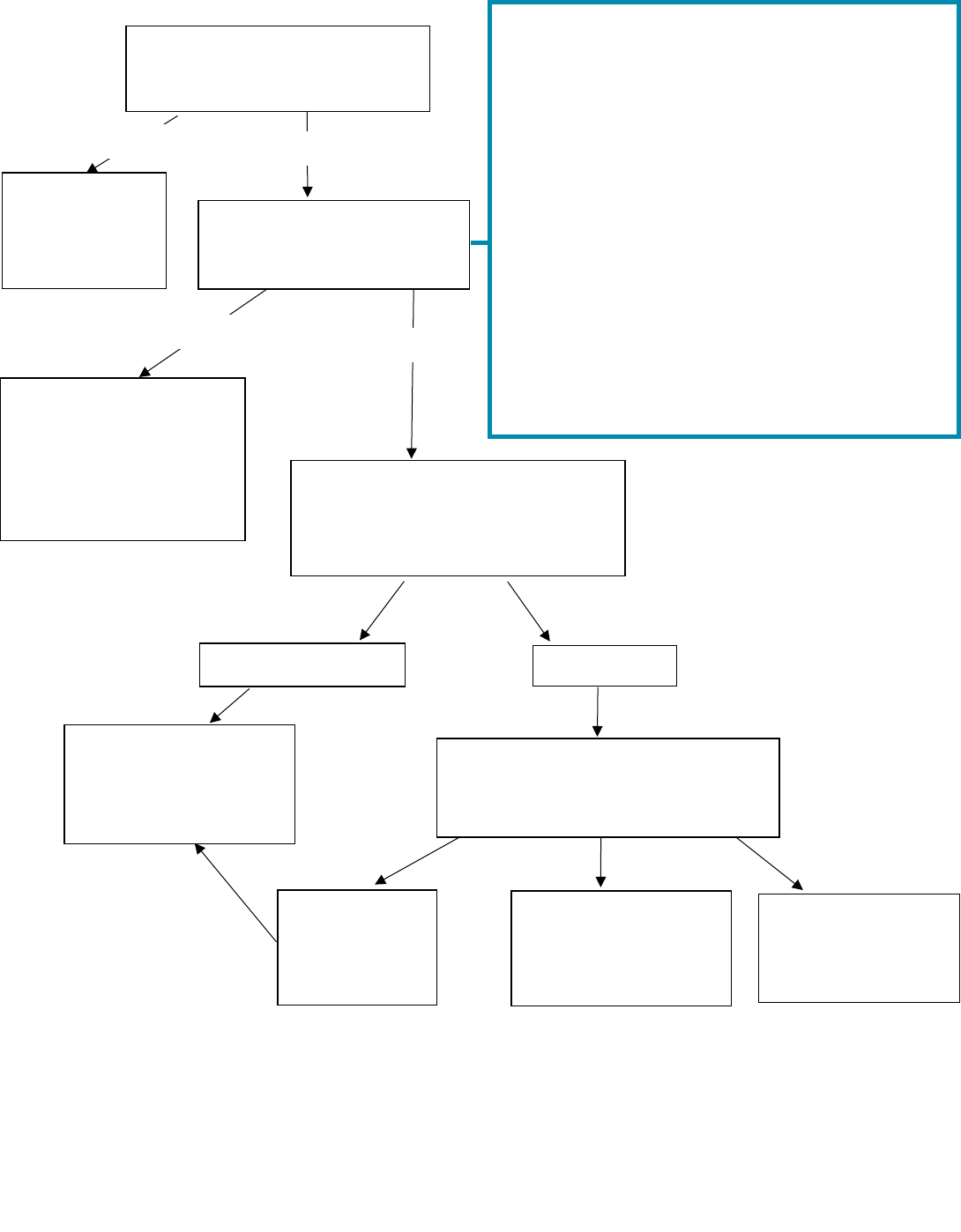

consider their destruction or disposal. (The Retention decision-making flowchart in Annex 1

provides further guidance).

Reviewing what you keep scenario

The process of review could be initiated by the impending departure of a member of staff from

the organisation (e.g. a PhD student moving on, a programme leader retiring, etc.). Principal

Investigators (PIs) have a key role to play in any decisions about the retention or destruction of

research data and/or samples collected, generated or used within their programme of research.

It is therefore particularly important that PIs are involved in any retention or destruction

decisions before they (or one of their students) moves on to another research organisation, or

the PI retires.

Where a Principal Investigator (PI) has a large collection of biological samples and data, then

it’s important for them to help determine:

• Whether anyone wants these samples and/or data?

o Perhaps the PI accessed the samples and/or data from a biobank or a data provider

and a legal agreement is in place stating the fate of the samples and/or data; or

o The PI or student is keen to take the samples and/or data with them to their new

research organisation; or

o Someone else within the current research team, another collaborator or a biobank

wants to take responsibility (or custodianship) of the data and/or samples;

• Whether the Principal Investigator is confident about the utility of the samples and/or data?

Have the samples been stored appropriately, is there any evidence to prove sample

utility? Similarly, is the data ready for sharing? Does it have appropriate high-quality meta

data? (Any recipients of the samples and/or data are likely to want to be assured of utility);

• Whether there are any restrictions which would limit the use of the samples and/or data?

Are any legal agreements in place which state what can and cannot be done with the

samples and/or data? Do the samples have specific storage requirements (e.g. do they

need to be kept in a -80 freezer?). For both the samples and data, does the consent in

place support the planned secondary use, do you have evidence of consent? (Again, any

potential recipients of the samples and/or data, are likely to want assurance in terms of

consent. Work with local contacts to determine what assurance is most appropriate in your

circumstances).

If the secondary use or retention of the data and/or samples will involve transferring them to

another organisation, then the transfer arrangements should detail any conditions of access and

eventual destruction (these arrangements could be outlined in a legal agreement). Where

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

9

relevant the Data Protection Officer(s) and/or the Designated Individual (or equivalent) in both

your organisation and the recipient organisation should be notified. You should also ensure that

the decision to transfer the samples and/or data is clearly documented, signed off and retained

for future reference (so that there is an enduring record to track what has happened to the

samples and/or data).

All decisions (i.e. either further retention / transfer, or the destruction of samples and/or data)

should be documented, signed off (by the Unit Director, Head of Department, Designated

Individual (or equivalent), Data Protection Officer(s) or sponsor representative) and kept for

future reference. This will ensure that there is a clear record of the fate of all research data

and/or samples within your organisation.

Good Research Practice: Principles and Guidelines recommends that research data relating to

studies which directly inform national policymaking or are of other historical importance, are

considered for permanent preservation. In some cases the potential impact on policy may be a

clear aim of the study, whilst in others this significance may only come to light later. It may

therefore be necessary to consider the impact of the study at several stages during its lifecycle,

particularly for studies which have long-term goals and run for many years. Once decisions

have been made about what to keep and in what format, what is held should be reviewed on an

ongoing basis. The table below suggests some timelines:

Suggested

retention periods

Potential decisions?

Less than 5 years

Retain physical data in its original form. Unless doing so would

render it unusable, e.g. would microscope slides fade and degrade

in this time?

Between 5-20

years

Make decisions with respect to what will be retained and in what

format. For example you may wish to consider scanning paper

records, or if you have any remaining biosamples, are these still

useful?

For electronic records, it would be timely to consider active

management of software and/or hardware. The impact of software

and/or hardware upgrades becomes more significant over time

and these begin to impact on the ability to access files. Therefore,

systematically checking files and upgrading any software and/or

hardware as necessary, will ensure continued access to your

research data.

More than 20

years

Consider destruction unless the research data are extremely

valuable

e.g. has informed national policy making / are of historical

importance or are from a “risky” participant group (e.g. ‘high risk’

study involving children, adults without capacity or contentious

research outcome).

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

10

3 Data curation and further use

It’s important to consider how data will be stored, maintained and accessed to ensure it remains

useable and retrievable for secondary or future research (particularly important for electronic

data, i.e. to ensure it can be accessed and continues to be accessible as technology advances).

The Concordat on Open Research Data promotes openly available research data for use by

others wherever possible.

3.1 Where will data be kept?

• Will you (the researcher) keep some/all of the data?

• Will it go to a repository?

• If your research will generate clinical information, will the resulting clinical data form part of

the patient’s medical record?

3.2 Who will curate the data?

• Will you (the researcher) maintain the data and any associated meta-data in a useable

format?

• Will agreements be put in place with another organisation to manage the data on your

behalf?

• How will access for secondary or future research or for reproducibility reasons be

facilitated?

3.3 How will access requests be managed?

• Will access be actively promoted, is the data and/or meta-data discoverable by other

researchers?

• Are data publicly available or available through a managed/controlled access process? For

datasets containing individual participant data MRC supports managed access.

• How are access requests reviewed, which criteria are used to make decisions?

• Will you be able to provide an extraction service by those with knowledge of the data and

storage systems? Will they help new users understand the data, will it be a collaborative

relationship? Long term, how will you retain this expert knowledge of the data?

• In what format will data be sent to the other party? Is secure data transfer required?

• How will you oversee usage, e.g. a data sharing agreement with recipients?

For further information on sharing research data please see MRC data management and

sharing; and for sharing individual participant data, please see MRC Methodology Hubs

guidance Good practice principles for sharing individual participant data from publicly funded

clinical trials.

Annex 1: Retention decision making flowchart for research data

and/or samples

MRC Regulatory Support Centre

Version 2, November 2022

11

Comply with

the terms of

the

agreement.

Retain data and/or

samples in line with

your organisation’s

policy

2

or arrange

transfer to the new

custodian

3

.

Your organisation.

Third party.

Consider destruction

or disposal in line

with your

organisation’s policy.

Destroy or dispose

of on behalf of third

party (retain record

of permission).

Return to third

party (retain

record of

decision).

NO

YES

YES

1.

You should consider the effort required to prepare your data and/or samples for sharing, before following

the ‘YES’ route. For example, is your data already collated? Does it have appropriate meta-data?

2.

All organisations should have a retention policy. MRC’s policy is outlined at 1.1.

3.

You should not arrange the transfer of data and/or samples on your own, involve the appropriate local

contacts (e.g. your sponsor representative, Data Protection Officer, Designated Individual as appropriate).

Is an agreement in place

which states the fate of the

data and/or samples?

If no

response or

contact is not

practicable.

NO

Are the data and/or

samples still needed?

(Please see box on right).

Who sponsored the research?

(If there was no sponsor, who

was the Principal Investigator’s

employer?)

Contact third party and obtain

decision over fate of data and/or

samples where practicable.

Things to consider in assessing whether data

and/or samples are still needed

If any of the following are likely, follow ‘YES’ route:

a) You will need to access the data and/or

samples to support further research (i.e. your

own research, or research done by others).

b) A new custodian is found for the data and/ or

samples (e.g. a collaborator, biobank, etc.)

1

c) Your research has/will lead to a high-profile

publication which could be challenged.

d) Your research includes Intellectual Property

(IP) rights (or there is potential IP)

e) Harm to participants (physical or psychological)

could be reported / discovered.

f) National policy might be influenced by your

findings or the results are historically important.

g) Any other reason that you may need access to

the data and/or samples in future.