University of Colorado Law School University of Colorado Law School

Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Colorado Law Scholarly Commons

Books, Reports, and Studies

Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural

Resources, Energy, and the Environment

2004

Evaluating the Use of Good Neighbor Agreements for Evaluating the Use of Good Neighbor Agreements for

Environmental and Community Protection: Final Report Environmental and Community Protection: Final Report

Douglas S. Kenney

Miriam Stohs

Jessica Chavez

Anne Fitzgerald

Teresa Erickson

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/books_reports_studies

Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Environmental Policy Commons

Citation Information Citation Information

Douglas S. Kenney et al., Evaluating the Use of Good Neighbor Agreements for Environmental and

Community Protection (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law 2004).

D

OUGLAS S. KENNEY ET AL., EVALUATING THE USE OF GOOD

NEIGHBOR AGREEMENTS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL AND COMMUNITY

PROTECTION (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch.

of Law 2004).

Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson

Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the

Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law

Center) at the University of Colorado Law School.

Final Report

EVALUATING THE USE OF GOOD

NEIGHBOR AGREEMENTS FOR

ENVIRONMENTAL AND

COMMUNITY PROTECTION

August 2004

Prepared by

Douglas S. Kenney

Miriam Stohs

and

Jessica Chavez

NATURAL RESOURCES LAW CENTER

Anne Fitzgerald

ANNE FITZGERALD ASSOCIATES

With contributions from

Teresa Erickson

NORTHERN PLAINS RESOURCE COUNCIL

Natural Resources Law Center • University of Colorado School of Law

© 2004, Natural Resources Law Center

University of Colorado School of Law

UCB 401

Boulder, CO 80309-0401

For more information about this report, contact Doug Kenney: (303) 492-1296;

This report can be reprinted and distributed without permission as long as proper attribution (citation) is

given and contents are not modified. While the authors believe the information herein to be accurate, the

analysis is subjective in nature and is based on information provided through interviews and surveys which,

in many cases, is impossible to independently verify.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Community groups in the United States occasionally enter into negotiated agreements

with local communities to alleviate negative environmental and public health impacts

associated with polluting industries. These so-called Good Neighbor Agreements (GNAs)

take a variety of forms, but typically commit the company to mitigate the offending

practices in exchange for the community group’s commitment to stop legal and public

relations challenges to business operations. Many community activists believe that

GNAs are a promising tool for community empowerment. This premise is explored in

the following review of 11 GNA case studies.

The overall conclusion and recommendation emerging from this study is that GNAs are,

in fact, a process worth pursuing in the right circumstances. Those circumstances are

varied, but at a minimum, require a company with the potential to address community

concerns while maintaining economic viability, and a community group with sufficient

leverage, resources and skill to move through the often long process. Five specific

findings are offered:

(1)

Environmental GNAs are Rare. Although the “GNA approach” has been in existence

for several years, it is still a fairly rare strategy used by community organizations to

address environmental, public health, and nuisance concerns.

(2)

The GNAs Studied are Generally Quite Effective. The case studies strongly suggest

that when used in appropriate circumstances, the GNA approach can be (and often is)

an effective and appropriate approach for a community group to address

environmentally-oriented company/community conflicts.

(3)

The Northern Plains GNA is Atypical. The arrangement between Northern Plains and

its partners with the Stillwater Mine is unusually sophisticated in terms of the scope

and complexity of the agreement, and the community group resources committed to

the GNAs successful implementation.

(4)

Formal—i.e., Written and Legally Binding—GNAs are Highly Desirable, but May

Not Be Essential to Achieving Implementation Success. Although there is not a direct

correlation between the formality of the agreements and their degree of

implementation success, having a written and binding agreement offers additional

opportunities to ensure compliance should the signatory company become

uncooperative.

(5)

GNAs Are Best Viewed as a (Long and Difficult) Process. Successfully utilizing the

“GNA approach” requires navigating three very different stages typically spanning

several years: (Stage # 1) getting the company to the negotiation table, (Stage # 2)

GNA negotiation/design, and (Stage # 3) implementation.

GNAs are not needed everywhere. But where the safety net of environmental law and

regulation is inadequate, GNAs can be a valuable tool for community activists.

iii

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

E

VALUATING THE USE OF GOOD NEIGHBOR AGREEMENTS FOR

ENVIRONMENTAL AND COMMUNITY PROTECTION

Executive Summary....................................................................................................iii

Table of Contents......................................................................................................... v

List of Acronyms ......................................................................................................vii

Introduction.................................................................................................................. 1

What are Good Neighbor Agreements?.................................................................. 1

What Evaluate GNAs? ........................................................................................... 1

Research Methods .................................................................................................. 2

The GNA Network............................................................................................. 3

Evaluation Metrics ............................................................................................ 4

Case Studies ................................................................................................................ 5

Selection of Cases .................................................................................................. 5

Overview of Cases ................................................................................................. 6

Similarities and Differences ................................................................................... 8

The Implementation Record .................................................................................. 9

Evaluating Success .................................................................................................... 11

Findings...................................................................................................................... 13

Concluding Thoughts and Recommendations .......................................................... 19

List of Tables

Table 1. Participants in the GNA Network.................................................................. 3

Table 2. Overall Success of GNAs (as reported by community group members)..... 12

Table 3. Prerequisites to Using the GNA Approach Successfully:

Stage 1: Forcing the Company to Negotiate......................................................... 17

Table 4. Prerequisites to Using the GNA Approach Successfully:

Stage 2: GNA Negotiation and Design................................................................. 18

Table 5. Prerequisites to Using the GNA Approach Successfully:

Stage 3: Implementation of the Agreement ......................................................... 19

v

Appendices

Appendix A: Relevant GNA Literature ................................................................... 21

Appendix B: GNA Survey ....................................................................................... 22

Appendix C: Stillwater Mine GNA Case Study (Finding a Path to Accord: A

Case Study of a Good Neighbor Agreement) ........................................................ 30

Appendix D: GNA Case Studies ............................................................................... 44

BREATHE & Syntex............................................................................................ 44

COCOA & Idaho Dairies...................................................................................... 48

C/LRTC & Sun Oil............................................................................................... 55

CCN & Shell Oil................................................................................................... 59

NPRC & Stillwater Mining Co............................................................................. 64

OCA & Rohm and Haas ....................................................................................... 71

SBESC/BCC & Seneca-Babcock Industries......................................................... 75

SEA & Unocal ...................................................................................................... 82

TUEF & Rhone-Poulenc....................................................................................... 90

WCTC & Chevron................................................................................................ 96

WSERC & Bowie Resources.............................................................................. 100

Appendix E: Summary of Survey Responses ........................................................ 107

Appendix F: Environmental GNA Evaluation Methodology ................................ 113

Appendix G: Newspaper Coverage of the GNA Workshop in 2002

(Knowledge, trust key to agreements, Dan Burkhart, Billings Gazette, 8/4/02). 123

Appendix H: Contracts: Definitions and Considerations ....................................... 127

vi

List of Acronyms

BAAQCD Bay Area Air Quality Control District

BCC Buffalo Common Council

BLM U.S. Bureau of Land Management

BREATHE Boulder Residents for the Elimination of Air Toxics and Hazardous

Emissions

BRL Bowie Resources Ltd.

CAC Citizens Advisory Council

CAFO Confined Animal Feeding Operation

C/LRTC Community/Labor Refinery Tracking Committee

CBE Communities for a Better Environment

CCN Concerned Citizens of Norco

COCOA Citizens of Owyhee County Organized Association

CRC Cottonwood Resource Council, Crockett/Rodeo Coalition

CWG Community Working Group

ECO Environmental Community Organization

EIS Environmental Impact Statement

GNA Good Neighbor Agreement

GNC Good Neighbor Committee

LABB Louisiana Bucket Brigade

NFCWG North Fork Coal Working Group

NPRC Northern Plains Resource Council (or Northern Plains)

OCA Ohio Citizen Action

vii

R&H Rohm and Haas

RP Rhone-Poulenc Basic Chemicals Company

SBESC Seneca Babcock Environmental Subcommittee

SEA Shoreline Environmental Alliance

SPA Stillwater Protective Association

SMC Stillwater Mining Company

TRI Toxic Release Inventory

TUEF Texans United Education Fund

TWC Texas Water Commission

WCTC West County Toxics Coalition

WSERC Western Slope Environmental Resource Council

viii

INTRODUCTION

The body of this Good Neighbor Agreement (GNA) evaluation report is relatively brief,

with most details and supporting material presented in a long series of appendices. The

report begins with this introductory section explaining what a GNA is and why and how

we conducted the evaluation. This is followed by an overview of the cases investigated

for this report, and an assessment of their success. Knowledge gained from these case

studies is then summarized as key findings, followed by concluding remarks. The

appendices that follow the main report contain a wealth of information, primarily

focusing on further describing the case studies (particularly the Northern Plains

arrangement with Stillwater Mine) and the research methodology.

W

HAT ARE GOOD NEIGHBOR AGREEMENTS?

In many locations throughout the United States, communities suffer negative

environmental and social impacts from neighboring industries. Conflicts are particularly

common in areas dominated by industries such as petrochemicals, manufacturing, and

mining. A variety of federal, state, and local laws, and their associated permitting

programs, provide some protections for local communities. However, these protections

are frequently viewed by communities as inadequate, often failing to recognize and

address the full range of local concerns, and enforced by agencies with a limited set of

remedies and, frequently, declining budgets and staffs. Additionally, these protections

can create regulatory costs and uncertainties detrimental to the companies and, in many

cases, the communities as well. Communities, companies, and governments often see a

need for better solutions.

Increasingly, community organizations—sometimes in conjunction with local

governments—are choosing to address these conflicts through the use of agreements

negotiated directly with the local companies. These so-called Good Neighbor

Agreements (GNAs) take a variety of forms, but typically are documents promising

company concessions and behavioral changes designed to reduce (and more fully

disclose) negative community impacts. Despite the positive sentiments evoked by the

“Good Neighbor” terminology, these concessions are typically the product of hard-fought

negotiations, and then, are only offered in exchange for a community commitment to stop

litigation, a permit challenge, or some other form of activism against the company.

W

HY EVALUATE GNAS?

In the summer of 2001, the Northern Plains Resource Council (hereafter “Northern

Plains” or NPRC) contracted with the Natural Resources Law Center and Anne

Fitzgerald Associates to conduct a three-year study of environmental GNAs. There were

several motivations for this study. First and foremost, Northern Plains is already a

signatory and active participant in a GNA with the Stillwater Mine (Montana), one of the

1

world’s largest producers of platinum and palladium.

1

While this is enough to make

Northern Plains an expert on the design and implementation of GNAs, the organization’s

experience with GNAs is nonetheless limited to this one example. In order to potentially

improve the functioning of this arrangement and to guide ongoing discussions about

potential new GNAs in other substantive areas (e.g., coalbed methane development),

Northern Plains felt that the organization could benefit from an outside perspective and

from a comparison of the Northern Plains GNA experience with others nationally. This

evaluation and review was to have at least two additional benefits. First, it would allow

the organization to better respond to the dozens of inquiries flooding in from other

community organizations considering the adoption of environmental GNAs, and

similarly, to better share knowledge among other groups that, like Northern Plains, had

some first-hand experience with GNAs. And secondly, such a review would be helpful in

guiding funders anxious to assist communities in the resolution of environmental

problems. Much like the community groups and companies that sign GNAs, the funding

community is interesting in generating maximizing return on its investments. An

evaluation of GNA performance could greatly inform these decisions.

These various motivations came together when the William and Flora Hewlett

Foundation, a long-time supporter of Northern Plains and their GNA arrangement,

offered to fund a three-year evaluation of GNAs, with the intention of generating

information that could be of use to Northern Plains, other community organizations with

or considering GNAs, and the funding community.

R

ESEARCH METHODS

This study is primarily based on a review of 11 case studies, with the majority of data

collection being accomplished through a written survey, the review of written documents

where available (including the GNA itself), oral interviews, and three workshops held in

Montana (at the end of year 1, 2 and 3 of research). This work was done collaboratively

among the research team, with most survey work and the literature review being

coordinated by the Natural Resources Law Center, most phone communications

conducted by Anne Fitzgerald Associates, and the hosting of workshops by Northern

Plains. The case study approach was seen as essential since there is not a rich GNA

literature, and since our goal is to identify lessons and trends that relate to the use of

GNAs in practice.

In all of this work, our communications were with the community groups—and not the

companies—involved in the GNAs. This focus on community groups persists in the

analysis of data and the formulation of conclusions. A companion study from the

perspective of the companies would undoubtedly be a worthwhile effort, but was

considered beyond the scope and intended audience of this investigation.

1

Palladium is a primary component in catalytic converters used to reduce automobile emissions. Only 3

mines worldwide produce palladium.

2

The GNA Network

A key source of information and insight in this study was the community leaders and

their consultants directly involved in the negotiation and implementation of the GNAs

studied. This so-called “GNA network” was consulted frequently during the study,

including in three workshops held in Montana. Some of the key contributors are listed

below in Table 1:

Table 1. Participants in the GNA Network

Richard Abraham, Texans United Education Fund

Rachael Belz, Ohio Citizen Action

Darlene Bos, Northern Plains Resource Council (Montana)

Arleen Boyd, Stillwater Protective Association (Montana)

Ruth Breech, Ohio Citizen Action

Aaron Browning, Northern Plains Resource Council (Montana)

Dawn Caldarelli, Seneca-Babcock Environmental Sub-Committee (New York)

Janet Callaghan, Shoreline Environmental Alliance (Rodeo/Crockett, California)

Iris Carter, Concerned Citizens of Norco (Louisiana)

Joan Chadez, Citizens of Owyhee County Organized Association (Idaho)

Henry Clark, West County Toxics Coalition (Richmond, California)

Ilene Dobbin, Citizens of Owyhee County Organized Association (Idaho)

Sarah Eeles, West County Toxics Coalition (Richmond, California)

Teresa Erickson, Northern Plains Resource Council (Montana)

Jack Heyneman, Stillwater Protective Association (Montana)

Jerry Iverson, Cottonwood Resource Council (Montana)

Kasha Kessler, Shoreline Environmental Alliance (Rodeo/Crockett, California)

Robyn Morrison, Western Slope Environmental Resource Council (Paonia,

Colorado)

Denny Larson, Refinery Reform Campaign (San Francisco)

Bill Nowak, Buffalo Common Council (New York)

Jeremy Puckett, Western Slope Environmental Resource Council (Paonia,

Colorado)

Michael Reisner, Northern Plains Resource Council (Montana)

Anne Rolfes, Louisiana Bucket Brigade

Jane Shellenberger, Boulder Residents for the Elimination of Air Toxics and

Hazardous Emissions (Colorado)

Amy Singer, Northern Plains Resource Council (Montana)

Garland Smith, Citizens of Owyhee County Organized Association (Idaho)

Wilma Subra, Louisiana Bucket Brigade

Tara Thomas, Western Slope Environmental Resource Council (Paonia,

Colorado)

Ed von Bleichert, Boulder Residents for the Elimination of Air Toxics and

Hazardous Emissions (Colorado)

Bob Wendelgass, Clean Water Action (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

And others …

3

E

VALUATION METRICS

Very little documentation exists regarding our relatively small set of case studies, a

reality that has influenced our selection of research methods. Given our small sample

size and our reliance on subjective opinions, we sought to provide some structure to our

qualitative conclusions by subjecting each case to the same set of evaluation metrics.

The selection of these metrics was not only driven by our data limitations and related

methodological constraints, but was also influenced by the broad goals of this study. Our

desire is to accomplish more than a simple determination of success or failure, but to also

develop a better understanding of why efforts succeed or fail, and what transferable

lessons can be pulled from this collective experience. Based on this set of reasons, we

ultimately selected a research approach that relies primarily on 3 evaluation metrics,

listed below in order of importance (most important listed first):

1. Actual program activities versus promised activities. To the extent that the GNA

requires specific actions (or inactions) at predetermined times (or under specific

circumstances), these standards provide a useful way to evaluate activities, outputs,

and potentially, outcomes.

2. Participant satisfaction and self-assessment. Presumably, participants have a good

idea of the suite of problem-solving options available to them, and of the costs and

benefits of pursuing the GNA strategy. Thus, their degree of satisfaction with the

GNA is a useful metric of the strategy.

3. GNA success versus other problem-solving opportunities. Communities can use a

variety of approaches to modify and/or control the activities of neighboring

companies. Ultimately, the efficacy of the GNA approach must be considered with

respect to what is potentially achievable using other tools—including those of a

regulatory, judicial, economic, and/or political nature.

Two additional metrics were also utilized to complement and further refine the analysis

of case study information:

4. Self-assessment of keys to success and failure. Success or failure can often hinge on

the availability of a key resource or circumstance that is best understood by

participants active in the negotiation and implementation of the GNA. By

understanding the keys to success and failure, informed judgments can be made about

the potential merits, application and transferability of the GNA approach.

5. Internal logic of the problem-solving strategy used in the GNA. One way to explain

the success or failure of a problem-solving strategy in a given situation is through an

institutional analysis approach that evaluates how the GNA effort has changed rules

influencing relationships, behaviors, and activities of key participants, and whether or

not this happened as intended.

A detailed discussion of the evaluation methodology is provided in Appendix F.

4

CASE STUDIES

SELECTION OF CASES

The research approach used in this study is based on the analysis of case studies.

Locating GNA case studies was a difficult process for many reasons. For starters, the

term “Good Neighbor Agreement” is poorly defined and is used inconsistently in a

variety of contexts; thus, it is difficult to decide what types of arrangements should be

included. In this investigation, we’ve decided to primarily focus on arrangements with

the following characteristics:

1. Feature a written agreement (i.e., an actual GNA document)

2

;

2. Located in the United States

3

;

3. Concerned primarily with environmental pollution or natural resource impacts

and/or the associated impacts on human populations

4

; and

4. Prominently involve one or more non-profit community groups.

These criteria reflect our need for cases offering parallels to the Northern Plains GNA

with the Stillwater Mine.

No central or comprehensive listing of GNAs currently exist. Based on our review of the

relevant—but exceedingly sparse and dispersed—literature (see Appendix A), and our

investigation of numerous Internet-based leads, we identified about 15 cases that

potentially fit our criteria. These cases were narrowed from a body of roughly 50 self-

defined GNAs in the United States.

Once this set of potential case studies was identified, we contacted key members of the

relevant community organizations and, where appropriate, followed through with a

general survey (see Appendix B). The decision to use a survey was based on our need to

develop a working knowledge of each case, to collect information in a standardized

manner (to facilitate comparisons), and to cultivate relationships with community leaders

that can contribute to, and ultimately use, this research. The survey was also useful in

fine-tuning our selection of case studies, since it is fruitless to pursue cases where we

2

Our thinking was two-fold: (1) that a written agreement would be necessary to locate and compile a case

study, and (2) that only a formal agreement would offer the promise of solving the issue of concern. This

guideline was violated by our inclusion of the Rohm and Haas agreement with Ohio Citizen Action. As

discussed later (particularly in finding # 4), the inclusion of this case study provided to be very worthwhile,

as the case illustrates a highly informal GNA model that can be very successful.

3

We do not have a full picture of GNA activity overseas, with the exception of the effort being led by

Friends of the Earth Scotland (see

http://www.foe-scotland.org.uk/nation/gna_report.pdf).

4

Note that the phrase “environmental GNAs” is defined herein to include agreements focused on human

health impacts associated with air, land or water pollution. This clarification is needed to distinguish these

GNAs from those focused on topics such as collective bargaining and banking, areas where some GNA

activity is believed to exist.

5

could not find an appropriate contact person, and thus, could not acquire a minimum level

of documentation. Based on this mix of technical and practical criteria, we ultimately

chose to include 11 case studies.

5

O

VERVIEW OF CASES

The case studies featured in this study are briefly summarized below (listed here by name

of participating company & primary community group(s)). More detailed reviews can be

found in Appendix D and, for the Stillwater/Northern Plains case, Appendix C. The case

studies (Appendix D) were primarily compiled from surveys (Appendix B) and from the

limited documentation available, particularly the GNAs themselves. In drafting the

Stillwater/Northern Plains case study, Anne Fitzgerald Associates supplemented this

information with a series of personal interviews.

Bowie Resources & Western Slope Environmental Resource Council (WSERC).

(Paonia, Colorado.) The GNA is primarily designed to limit truck and rail traffic and

noise associated with increased production at a coal mine. The GNA, adopted in

2000, was an outgrowth of a federal coal permit challenge which threatened to delay

mine expansion for several years. The GNA provided the community with a

mechanism for addressing the traffic issues—which was not covered in the EIS—and

allowed the company to move forward quickly with expansion.

Chevron Refinery & West County Toxics Coalition (WCTC), Communities for a

Better Environment (CBE), and People Do!. (Richmond, California.) The GNA was

inspired by a variety of public health and nuisance concerns associated with pollution

discharges and Clean Air Act violations from the Chevron refinery. When the

refinery sought a state air quality permit to (ironically) start manufacturing new

“clean fuels,” a permit challenge was initiated, prompting GNA negotiations leading

to adoption of an agreement in 1992 calling for reduced pollution, increased

monitoring, and investments in the local economy.

Rhone-Poulenc & Texans United Education Fund (TUEF). (Manchester-Houston,

Texas.) The GNA addresses the community’s public health and nuisance (odors,

noise, traffic) concerns associated with emissions from a chemical plant. A major

chemical spill and a pending permit mobilized the community to seek the GNA,

which was adopted in 1992 as part of the permit issued by the Texas Water

Commission.

Rohm and Haas & Ohio Citizen Action (OCA) and Environmental Community

Organization. (Cincinnati, Ohio.) The agreement addresses air quality and noise

issues associated with a chemical plant. In response to public pressures resulting

from an aggressive canvassing and media strategy, the company agreed in 1991 to an

5

The 11 cases actually cover 13 GNAs (since the 3 Seneca-Babcock industries are treated as one case).

Additionally, some of our advisors and members of our GNA network have experience with multiple cases,

which undoubtedly increases the value of their opinions and insights.

6

informal and non-binding agreement that addresses the public health and nuisance

concerns through a Community Advisory Council.

Seneca-Babcock industries (PVS Chemicals, BOC Gases, and Natural

Environmental, Inc.) & Buffalo Common Council and Seneca Babcock

Environmental Subcommittee (SBESC). (Buffalo, New York.) The GNA is actually

a series of three agreements addressing a variety of environmental, public health, and

nuisance concerns associated with three chemical companies. Bad publicity (in part

due to spills) and governmental pressure prompted negotiations leading to agreements

signed in 1995-1997 focusing on pollution prevention, community notification and

involvement, and public health and safety.

Shell Oil & Concerned Citizens of Norco (CCN). (Norco, Louisiana.) The GNA is

the culmination of a lengthy and bitter fight concerning public health and nuisance

impacts experienced by families living adjacent to a refinery and a chemical plant.

The agreement promises funds to relocate the most affected individuals.

Stillwater Mining Company & Northern Plains Resource Council (NPRC), Stillwater

Protective Association, and Cottonwood Resource Council. (Billings, Montana.) The

GNA addresses concerns relating to environmental protection and the community

impacts of new workers being brought in to increase production at a palladium mine.

Community groups used pending permits and threatened lawsuits together with a

negative publicity campaign to force a negotiated agreement in 2000 that addresses

key community concerns while allowing mine operations/expansion to proceed. (See

Appendix C for a detailed discussion.)

Sun Oil & Community/Labor Refinery Tracking Committee (C/LRTC) and the City

of Philadelphia. (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.) The GNA addresses public health and

quality of life issues associated with sulfur dioxide emissions from a refinery.

Negotiation and adoption of the GNA derived from a lawsuit inspired by Clean Air

Act violations. The GNA was enacted in 1997 as a consent decree to the lawsuit,

which has since expired.

Syntex Chemicals & Boulder Residents for the Elimination of Air Toxics and

Hazardous Emissions (BREATHE). (Boulder, Colorado.) The GNA mitigates the

public health and nuisance impacts of air emissions from a pharmaceutical company.

The agreement, initiated by the company and adopted in 1995, was inspired by high

emissions reported in the Toxic Release Inventory and by threats by citizens and local

government to block needed building permits for a proposed expansion.

Unocal & Shoreline Environmental Alliance (SEA), Communities for a Better

Environment, and the Crocket/Rodeo Coalition. (Crockett/Rodeo, California.) The

GNA addresses public health concerns associated with chemical releases from a

refinery. Several highly dangerous spills/releases prompted citizens to challenge the

refinery’s expansion permits, leading to negotiations that culminated in the agreement

in 1995.

7

Idaho Dairies & Citizens of Owyhee County Organized Association (COCOA).

(Marsing, Idaho). The GNA addresses the impacts on water and air quality

associated with large-scale dairy operations, particularly the disposal of manure.

Negotiations were prompted by a citizen challenge of a water permit needed by the

dairy. The GNA, signed in 1998, is included in the state water permit. Originally the

GNA applied to only one dairy but was later extended to a second dairy owned by the

same operator.

S

IMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

Overall, the cases offer enough similarities to ensure that comparisons are meaningful,

while featuring sufficient variation to support useful contrasts. Appendix E provides a

statistical summary of the information gathered; the following paragraphs summarize

some key highlights.

Perhaps the strongest similarity among the cases is the history of how the GNA came into

being. With remarkably few exceptions, the following narrative appears to be an

accurate summary of each of our case studies:

A company (normally profitable) repeatedly ignores community

complaints about pollution (nuisance, public health, and environmental

concerns) and related impacts until a time at which it needs a new permit

(often as part of its expansion plans) or it violates an existing permit (e.g.,

a sulfur dioxide spill). This provides a focal point for community

opposition, and can provide an opportunity for community groups, by now

often organized into local coalitions, to threaten a lawsuit, a permit

challenge, and/or other forms of and activism. This tactic is generally

augmented by a public relations campaign. The intent of the community is

rarely to close the company, but rather to force resolution of community

concerns outside the scope of, or beyond the apparent interest or ability

of, governmental regulators. Fearing a lawsuit—where delays are as

much a concern for the company as a potential negative verdict—or the

rejection of permits, and wanting to turn bad publicity into good,

companies accept (often begrudgingly) a community’s offer to negotiate.

The resulting GNA outlines a plan for addressing community concerns,

often employing creative remedies not usually available through

regulatory or litigation mechanisms. The breadth and strength of the

resulting GNA is closely correlated to the amount of leverage held by the

community group at the time of negotiation.

6

6

The experience of the Stillwater Mine GNA, for example, follows this pattern. The relationship between

the mine and the local community became strained in 1997-1998, when the company sought the permits

necessary to significantly expand production, to build a new impoundment, and to establish “man camps”

for new workers. These modifications threatened to produce a variety of environmental, public health, and

nuisance problems. Nonetheless, the permitting and EIS processes led by the U.S. Forest Service and the

8

The greatest point of difference among the case studies is arguably the size of the

community groups involved. Annual budgets of these groups range from $500 to $2.1

million dollars; similarly, the number of paid staff positions range from 0 to 170. There

is also significant variation in the industries involved, ranging from dairies to mines to

refineries. However, in many respects, these industries are ultimately quite similar in that

they each produce emissions (pollution) that are mobile and, thus, problematic to

neighboring communities. Addressing these transboundary impacts—what economists

call externalities—is notoriously difficult, as polluting industries usually lack the

economic incentives to change behavior since the benefits of this changed behavior are

unlikely to show up as profits on the company’s balance sheet. For this reason,

environmental law imposes regulations on polluting industries, and tools such as citizen

lawsuits and permit challenges empower communities to help ensure that regulations are

enforced even when the relevant agencies fail to act. Public relations pressure can also

provide a source of leverage promoting changed company behavior. A “good neighbor,”

therefore, is one that has reached a point at which it becomes more profitable to cease the

offending behavior than to continue and face community opposition.

7

T

HE IMPLEMENTATION RECORD

The implementation record of the case studies is more similar than different, and is

generally positive. The degree to which GNA commitments have been honored reflects

many factors, including not only the strength of the agreements, but also the attitudes of

the companies involved, the vigilance of the community groups, the age (and stage) of

the agreements, and the ease to which community concerns are readily resolved through

technological fixes or other readily-identifiable strategies.

8

One of the most successful cases is the most informal of the GNAs investigated: the

agreement between Rohm and Haas and Ohio Citizen Action. In this case,

chloromethane emissions have been reduced dramatically (almost entirely), while idling

trucks have been removed from the neighborhood. What this GNA lacks in legal

formality it apparently compensates for in the strength of the community group (Ohio

Citizen Action) and the cooperative spirit of the plant manager.

Implementation of the two mining-related GNA cases also has gone well. The contract

between Bowie Resources and the Western Slope Environmental Resource Council

Montana Department of Environmental Quality approved the expansion plan, triggering a lawsuit by the

Stillwater Protective Association. Concerned about the costs, delays, uncertainties, negative publicity, and

incomplete solutions often typical of litigation, the mine and community activists soon agreed to negotiate

a GNA. By 2000, a legally binding agreement was in place that provides land, water and community

protections, and that gives locals access to the mine’s operations. (A brief description of this case is found

in Appendix D; a detailed discussion is found in Appendix C.)

7

Despite the near uniform (and well-justified) frustration with regulatory agencies expressed by the

community groups in this study, it is worth noting that the very fact that often small community groups

have been able to entice companies to negotiate GNAs is evidence that the US system of environmental

regulation has real strengths.

8

Implementation histories are included as part of the case studies in Appendix D.

9

(WSERC), for example, has resulted in rerouting of truck traffic to a new load-out facility

and the implementation of noise mitigation measures. Some elements of the agreement

did not survive the company’s recent bankruptcy proceedings, although this has not yet

proved to be problematic. The agreement between Stillwater Mine and Northern Plains

(and others) also has been successful in many ways. The establishment of the busing

program for mine workers is among the most visible accomplishments, although for this

and many other issues addressed by the GNA, implementation has required a large

commitment of staff time and ongoing pressure on the mine—which has recently

changed ownership. If not for the GNA provision requiring the mine to fund some of

Northern Plains’ oversight expenses, the level of progress achieved would likely be

noticeably lessened.

Two cases involving chemical companies also appear successful and largely complete,

although in both cases a lack of data regarding implementation and the difficulty in

identifying individuals still involved in the cases makes detailed assessments difficult.

The oldest of the two agreements is the GNA between Rhone-Poulenc and Texans United

Education Fund, which appears to have achieved the goal of involving the Citizens

Advisory Committee (CAC) in many aspects of company planning and decision making

regarding health and nuisance (odors, noise, traffic) concerns. In the GNA between

BREATHE and Syntex Chemicals (Boulder), the emissions reduction program is also

believed to have been relatively successful, however, BREATHE has dissolved and very

little monitoring data exists to track compliance with the terms negotiated.

Another of the mature agreements is the GNA between the Community/Labor Refinery

Tracking Committee and Sun Oil (Philadelphia) which expired with the federal consent

decree in which it was enacted. Most items, including installation of the sulfur recovery

units, were implemented, but implementation required constant pressure from the

community, and the local air quality has not noticeably improved.

Somewhat similar implementation histories are associated with two refineries in

California. The GNA between Chevron and the West County Toxics Coalition (WCTC)

(Richmond) has featured partial implementation success, as leakless valves were installed

and a community health center was established. Fenceline monitoring and long-term

funding of the health center have not been achieved, however, as community attention

has shifted to other issues. The GNA between Unocal and Shoreline Environmental

Alliance (SEA) (Crockett/Rodeo) has also produced some successes, but overall the

implementation history has been disappointing as both the company and the community

groups have gone through transitions. Since the GNA was signed, SEA and CBE are no

longer strong and vibrant organizations; similarly, the Unocal facility has been sold twice

(and is now Conoco/Phillips). Some health studies were completed, mitigation funds

were awarded, and emergency warning equipment is now in place, but many other

provisions are likely to remain unaddressed. These cases illustrate the long-term

challenge of GNA implementation.

The most recent of our refinery cases involves Shell Oil and Concerned Citizens of

Norco. The deal negotiated is clearly a mixed bag, as most citizens covered by the

10

agreement have now been able to relocate (a few families have chosen to stay), but

compensation for property and moving expenses has been low and difficult to obtain, and

long-term health care issues remain unaddressed. The GNA was clearly beneficial, but it

was nonetheless a very partial and ultimately inadequate solution to the most horrific of

the cases in this study.

A mixed track record also characterizes the GNAs negotiated between the three Buffalo,

New York companies (PVS Chemicals, BOC Gases, and Natural Environmental, Inc.)

with the Seneca Babcock Environmental Subcommittee (SBESC) and Buffalo Common

Council (BCC). The most successful of the three has been the agreement with National

Environmental Inc., which has now addressed most community concerns relating to truck

traffic and noise. The implementation record with BOC Gases and PVS Chemicals has

been spotty at best. The problems with BOC Gases stem from the facility “going remote”

(i.e., becoming largely computerized and mechanized). The most notable success from

the PVS Chemicals GNA has been the establishment of the CAN system, a computerized

telephone system used to alert community residents of spills or other emergencies.

The remaining case study is the GNA between Idaho Dairies and Citizens of Owyhee

County Organized Association (COCOA). Initial progress under this GNA is

encouraging, particularly the voluntary extension of the GNA to a second dairy and the

establishment of water monitoring programs. However, the financial and staff demands

on COCOA remain high, and the impact of the dairies on local water resources has not

been addressed; thus, much work remains to be accomplished.

EVALUATING SUCCESS

As stated earlier, three primary “metrics” are being employed to measure the degree to

which the GNAs studied are considered successful: (1) actual program activities versus

promised activities; (2) participant satisfaction and self-assessment; and (3) GNA success

versus other problem-solving opportunities. Each metric is difficult to apply in practice,

and each tells only part of the story of how useful and appropriate the GNA approach has

been. Presumably, the first and, perhaps, the third metric can be applied by an

independent observer with adequate data, whereas the second metric comes directly from

the opinions of the community group participants. However, as a practical matter, it is

difficult to limit community group member opinions to just the second metric, as the

study was highly reliant on basic data from community group participants. Also

problematic is the fact that the cases are in different stages of completion. For these and

other reasons, the evaluations offered by both the study authors and the community group

participants are both highly subjective and inherently qualitative. Fortunately, there are

only a few areas of disagreement, and these are relatively minor.

The opinions on GNA success provided by community group members (in survey data)

are summarized below in Table 2:

11

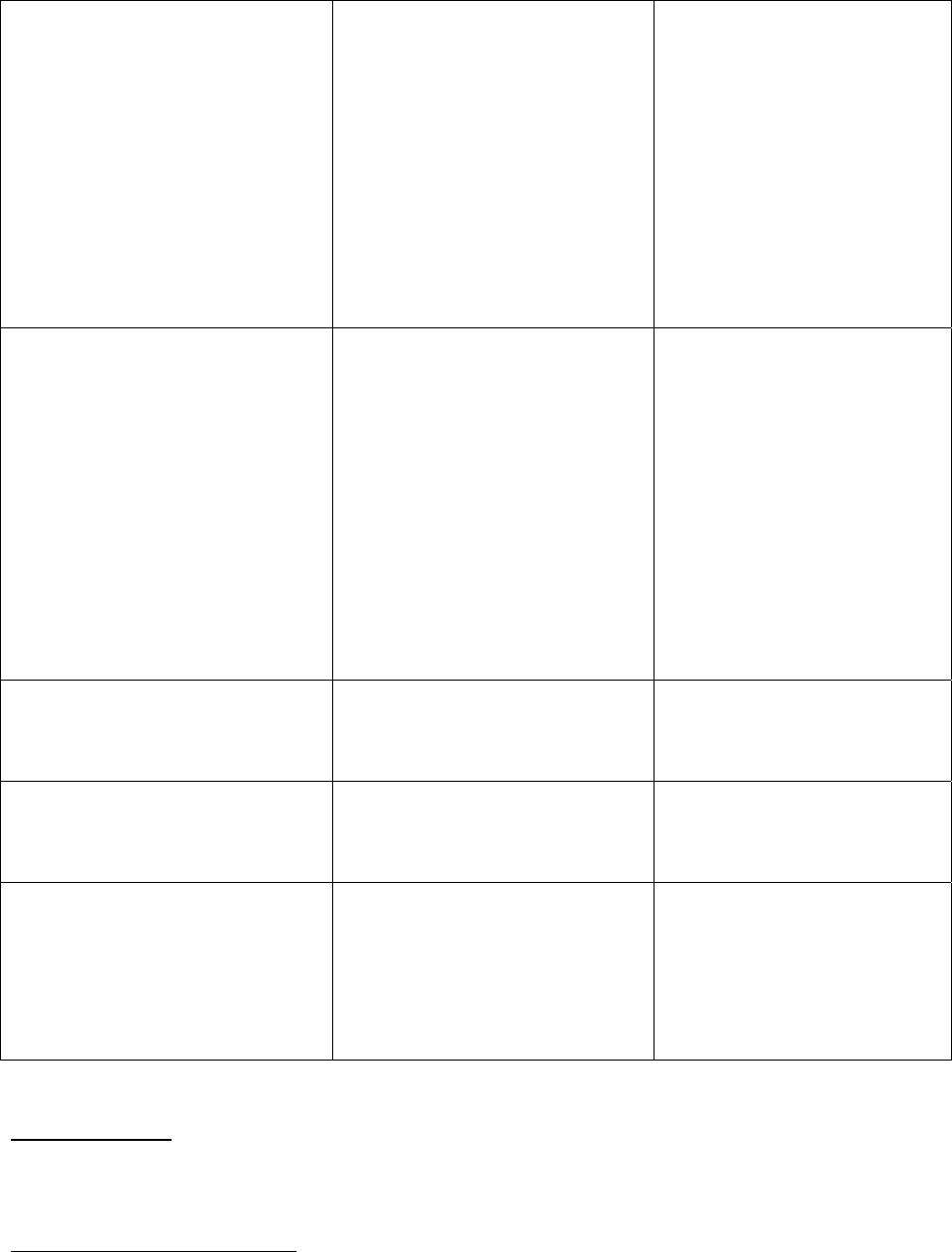

Table 2. Overall Success of GNAs (as reported by community group members)

Name of

Community

Group

Commitments Honored

a

Rating: 1 to 10 (10 is best)

Overall Success

b

Rating: 1 to 10

(10 is best)

Would you do

it (the GNA)

again?

TUEF 9.5 9.5 Yes

WSERC 10 9 Yes

WCTC 9, 10 [9.5] 8, 10 [9.0] Yes, Yes

NPRC 9 9 Unsure

OCA 9.5 9 Yes

BREATHE 7-8, 8 [7.8] 8, 9 [8.5] Unsure,

Most Likely

C/LRTC 8 8 Unsure

COCOA 8 8 Yes

LABB 10 7 Unsure

SBESC/BCC 5-6, 7 [6.3] 5, 6 Yes, Yes

SEA 4 5 No

AVERAGES 8.3 8.0

a = evaluation metric # 1; b = evaluation metric # 2.

WSERC = Western Slope Environmental Resource Council; WCTC = West County Toxics Coalition;

TUEF = Texans United Education Fund; OCA = Ohio Citizen Action; SBESC = Seneca-Babcock

Environmental Subcommittee; NPRC = Northern Plains Resource Council; C/LRTC =

Community/Labor Refinery Tracking Committee; BREATHE = Boulder Residents for the Elimination

of Air Toxics and Hazardous Emissions; SEA = Shoreline Environmental Alliance; LABB = Louisiana

Bucket Brigade; COCOA = Citizens of Owyhee County Organized Association.

Multiple responses mean more than one individual completed a survey. Multiple responses from a

single group are averaged [shown in brackets] for purposes of calculating the overall averages.

The SBESC ratings are for all 3 GNAs combined (of which one was generally successful and two were

not).

Based on the information available, these “self assessments” offered by the community

group participants seem reasonable with very few exceptions.

9

Specifically, the GNA

ranking by the WCTC representatives now seem generous given the recent “backsliding”

of the company (e.g., declining support of the health center), while the GNA ranking by

the SEA representative appears somewhat pessimistic given that the initial failure to

relocate the school and the ongoing problem with the distribution of mitigation fund

money are not problems that can be described as a failure of the company to honor

commitments.

10

Also somewhat questionable is the description by the LABB

representative that GNA commitments in the Norco case have been completely honored

(10 out of 10). This ranking does not reflect recent difficulties with relocation, but was

likely a reasonable response at the time the survey was completed.

11

Also, it is

9

These “independent evaluations” come exclusively from the lead author, Doug Kenney.

10

Implementation histories are provided as part of the case studies in Appendix D, and summarized in

implementation tables. Due to data limitations, there is no implementation table for the BREATHE case.

11

At the time the surveys were conducted, we did not have the cooperation of a member of CCN

(Concerned Citizens of Norco), so we relied upon the judgment of technical consultants associated with

LABB (Louisiana Bucket Brigade). Over the course of the study, we recruited a CCN member to the GNA

network and updated our knowledge of this case significantly.

12

worthwhile to note that the rankings offered by the SBESC/BCC respondents were an

attempt to collectively summarize the response of three different GNAs, one of which has

clearly been successful (with Natural Environmental, Inc.) while the other two have been

only marginally beneficial (with BOC Gases and PVS Chemicals).

The third of our primary evaluation metrics—a comparison of GNA success versus other

problem-solving opportunities—is particularly difficult to apply, given that it requires a

judgment regarding the outcomes potentially achievable using other problem-solving

techniques. Nonetheless, two observations are worth noting. First, in every case, the

GNA was not the first technique used to resolve the problem, nor was it used in isolation

from other techniques and tools (such as lawsuits, permit challenges, public relations, and

so on). To the contrary, the GNA approach was used as a way to harness these other

techniques and tools into a coordinated problem-solving effort finally capable of yielding

results. Secondly, this coordinated problem-solving effort (of which the GNA was the

centerpiece) undoubtedly achieved a long list of outcomes likely impossible through

other means. The high flexibility of the GNA tool is apparent from even a cursory

review of the type of concessions gained by communities: e.g. citizen/community

involvement in company operations, outside reviews of facilities, relocation of families,

worker busing programs, elimination of nuisances (e.g., idling buses), community

investments (e.g., health centers, parks), information sharing, and so on. The fact that

only one survey respondent pledged not to use a GNA in future disputes (while a

majority said they would) further illustrates the opinion that this tool can accomplish

outcomes not readily available through other means.

FINDINGS

The information and analysis featured in this report support five major themes and

conclusions regarding the current state of environmental GNAs:

(1)

ENVIRONMENTAL GNAS ARE RARE. Although the “GNA approach” has been in

existence for several years, it is still a fairly rare strategy used by community

organizations to address environmental, public health, and nuisance concerns.

Of course, the manner in which GNAs are defined shapes the number of identified case

studies. The range of GNA studies is larger if the defining criteria are relaxed, and if

non-environmental GNAs are included. For example, a variety of GNAs have been

pursued (including many by Ohio Citizen Action) that we chose not to investigate

because of their informality (“handshake GNAs”); similarly, we found evidence of GNAs

in non-environmental fields such as collective bargaining and labor relations. The lack of

GNAs in the environmental field is reflective of the strong history of relying on

regulation, litigation outcomes and permitting processes, and perhaps more importantly, a

history of activists trying to eliminate “offending” industries completely.

12

Authors of

12

Many of the industries featured in these case studies are frequently targeted by the so-called NIMBY

movement (Not In My BackYard).

13

GNAs, in contrast, do not seek to drive industry out of the region, but rather seek to shape

industry practices to better respect and protect community values. It is this quality, more

than any other, that is at the heart of the “good neighbor” terminology.

(2)

THE GNAS STUDIED ARE GENERALLY QUITE EFFECTIVE. The case studies strongly

suggest that when used in appropriate circumstances, the GNA approach can be

(and often is) an effective and appropriate approach for a community group to

address environmentally-oriented company-community conflicts.

Most of the members in our GNA network are happy with their arrangements, and for

good reason. If the SBESC case study is disaggregated into 3 cases, this study features

13 GNAs of which 10 are likely to meet most definitions of success. Even those that are

problematic—i.e., the SBESC arrangements with BOC Gases and PVS Chemicals, and

the SEA arrangement with Unocal (now Conoco/Phillips)—have been partially

successful (although the future of BOC Gases is in question). It is important to note,

however, that this success has come at a significant price in terms of personnel and

budget; as discussed below (particularly in findings # 3 and 5), achieving success through

the GNA approach normally requires a significant amount of effort and resources.

(3)

THE NORTHERN PLAINS GNA IS ATYPICAL. The arrangement between Northern

Plains and its partners with the Stillwater Mine is unusually sophisticated in

terms of the scope and complexity of the agreement, and the community group

resources committed to the GNA’s successful implementation.

There is much that other groups could learn from the NPRC GNA with the Stillwater

Mine, but perhaps most important is that the complexity of the GNA should not exceed

the capacity of the community group to ensure monitoring and implementation. While

this GNA is clearly successful, it is not an appropriate model for groups without a

comparable level of resources and longevity. One source of implementation resources is

funding from the mine for NPRC’s GNA monitoring and oversight expenses—a

concession that most members of our GNA network found remarkable and desirable in

future GNAs.

13

As the apparent “Cadillac” of GNAs, this GNA undoubtedly offers some

useful insights about what future GNAs should look like, but at the same time, it likely

presents a model that is unrealistic for groups with lesser resources.

It is important to note, however, that while we conclude that the vast organizational

resources of NPRC are essential to the implementation of its GNA, and that

organizational resources (i.e., budget and staffing) in general are an extremely valuable

asset to groups considering GNAs, such resources are not always essential. COCOA,

BREATHE and SBESC, for example, have all produced notable successes using GNAs,

13

The argument has been made that accepting implementation money from the company can potentially

lead to cooptation. While this may be a concern in some cases, a more serious concern is community

groups without sufficient resources to monitor and ensure implementation.

14

while operating on a collective annual budget of under $20,000 annually.

14

Organizations

lacking extensive resources are clearly at a disadvantage when using the GNA tool (and

all other problem-solving tools for that matter), but it is a disadvantage that can often be

overcome by a sound strategy and committed leadership (as described in finding # 5).

(4)

FORMAL—I.E., WRITTEN AND LEGALLY BINDING—GNAS ARE HIGHLY DESIRABLE,

BUT MAY NOT BE

ESSENTIAL TO ACHIEVING IMPLEMENTATION SUCCESS.

Although there is not a direct correlation between the formality of the agreements

and their degree of implementation success, having a written and binding

agreement offers additional opportunities to ensure compliance should the

signatory company become uncooperative.

This finding is largely influenced by the approach used by Ohio Citizen Action (OCA)

which relies on canvassing and letter writing to pressure companies to agree to address

problems, but does not require signed contracts or agreements. This approach has been

used with great success in the OCA case with Rohm and Haas (described herein), and in

other contexts as well—including the ongoing campaign with AK Steel.

15

This compares

favorably with the most “legally bulletproof” of the agreements—the now-expired

arrangement between C/LRTC and Sun Oil (Philadelphia) enacted in a federal consent

decree—where the company’s implementation record was considered good but not

exceptional (estimated by the community representative as 80 percent compliance), and

was achieved only under constant community pressure. It is likely that most community

groups will conclude, wisely, that formal agreements provide a valuable source of

ongoing leverage useful in ensuring GNA implementation.

16

But the case studies

reviewed in this study suggest that formal agreements are not always essential, and

conversely, that signed and apparently legally-binding agreements do not ensure

successful implementation.

14

Budget information for WCTC is not available, but is likely quite modest as well. In contrast, NPRC has

an annual budget of approximately $800,000.

15

Already, the AK Steel campaign has turned over 30,000 letters from citizens into company commitments

to spend $65 million on air pollution controls.

16

Designing an agreement that companies cannot easily “dodge” or “escape from” is a common goal of

groups pursing GNAs, and is a challenge where legal expertise can be extremely beneficial. In negotiating

with a company, it is good idea for the community group to have an understanding of contract law. A brief

primer on contract law is provided as Appendix H. Enforcement of agreements is always an overriding

concern. One of the most promising approaches to ensure enforcement is to have a GNA enacted as part of

a federal consent decree, which empowers the community group to return to the judge for enforcement (if

necessary) during the life of the decree. Another strategy is to have the terms of a GNA enacted as part of a

permit. No approach, however, is truly “bulletproof,” as changes in ownership and company bankruptcy,

and other factors, can test even the most carefully constructed agreements. Whether or not a GNA survives

a change in ownership can vary from state to state as the rules differ. If your state does not offer adequate

protections, a group may be able to address the issue through the use of covenants, or by making

acceptance of the GNA a condition of a permit (if the agency will agree). Strategies to make a GNA

survive a company bankruptcy are also multi-faceted, but can include the use of escrow accounts,

performance bonds, or even obtaining a security interest in the property. Regardless of the challenge faced,

good (and creative) legal advice during agreement negotiation can be highly beneficial.

15

(5)

GNAS ARE BEST VIEWED AS A (LONG AND DIFFICULT) PROCESS. Successfully

utilizing the “GNA approach” requires navigating three very different stages

typically spanning several years: (Stage # 1) getting the company to the

negotiation table, (Stage # 2) GNA negotiation/design, and (Stage # 3)

implementation.

Successfully addressing the problems of concern in a GNA requires completion of all

three stages; the process can fail at any of these stages. The key to negotiating this

process is best defined in terms of leverage and resources. Both of these variables can

be—and typically need to be—augmented and maintained by the community group

throughout the GNA process. This requires planning and strategic thinking. Leverage

can come from many sources, from exploiting legal requirements (both substantive and

procedural), to gaining access to company information (and technical knowledge), to

applying traditional, grass-roots activism. Also critical is the importance of a “focal

point,” such as a permit application or an emergency discharge. Large, well-established

community groups—i.e., those with extensive staffing and funding resources—are best

positioned to take advantage of these ingredients, but as suggested earlier, several

strategies exist that smaller community groups can potentially use to augment leverage

and/or resources, or to reduce the administrative burdens typically associated with

applying the GNA approach. Strategies include: self-executing agreements (e.g., upfront

payments or one-time actions; transferring enforcement to an agency, such as in a

permit), or requiring the company to finance some of the community group’s

implementation activities. Smaller groups may also find it advantageous to form

partnerships or coalitions with other entities

17

, thereby broadening the base of

organizational resources.

18

Finally, we acknowledge that a single motivated activist can

be remarkably effective. As usual, there appears to be no substitute for leadership and

personal commitment.

Our findings regarding the salience of leverage and resources are summarized below in

Tables 3 through 5. These topics are also discussed extensively in the GNA Handbook

prepared by the NPRC as part of this study.

17

It is worth noting that members of the GNA network report that mainstream national environmental

groups are rarely helpful to groups pursuing GNAs. In fact, community organizations seeking GNAs are

frequently criticized by environmentalists and environmental justice advocates for “selling-out.”

18

COCOA, for example, is now a member of the Idaho Rural Council.

16

Table 3. Prerequisites to Using the GNA Approach Successfully:

Stage 1: Forcing the Company to Negotiate

Sources of Leverage

• Company needs a permit or similar public approval

• Company is vulnerable to a lawsuit (particularly related to

environmental law compliance)

• Company requires/desires good public relations (or must

avoid bad publicity) in order to maintain or expand

profitability

• A change in company personnel/ownership creates an

opportunity for a new relationship

Resources /

Strategies

• Litigation and/or permit challenge

• Publicity, media relations, and activist strategies (e.g.,

letter writing, editorials, demonstrations)

• Leadership; willingness of leaders (on both sides) to “try

something new”

• Knowledge of the company’s needs/desires

• Environmental data (e.g., monitoring results)

Other Advice /

Observations

• Have a very clear idea of what you want before entering a

negotiation; have a “bottom line” established

• Articulate the possibility of a win-win solution

• Pick your fights carefully, and be prepared to deliver on

threats

• Begin research on the company and its manufacturing

processes; consult outside experts if needed

• Beware being coopted or diverted through a company-

controlled Citizens Advisory Council

17

Table 4. Prerequisites to Using the GNA Approach Successfully:

Stage 2: GNA Negotiation and Design

Sources of Leverage

• Must have something valuable to offer (e.g., drop a permit

challenge or lawsuit; end bad publicity; assist in permit

approval and generating good publicity)

• Must have demands/requests that the company can

theoretically meet

Resources /

Strategies

• Negotiation skills/training; coherent negotiating strategy

• Adequate understanding of technical issues (e.g., science,

law); must have appropriate data (e.g., monitoring data,

company profile)

• Must have a strategy for structuring an agreement that

facilitates implementation and real problem-solving (e.g.,

the agreement must provide leverage/resources for

implementation)

Other Advice /

Observations

During GNA Negotiation:

• Select negotiators carefully

• Transcribe negotiations

• Establish and enforce negotiation deadlines; understand

that many companies’ strategies are designed to wear

down communities (e.g., delays during negotiation,

providing too much information, agreeing to things they

plan to later fight during implementation, etc.)

• Maintain community organization and activism

throughout the process; maintain a unified front; guard

against cooptation

• Cultivate and maintain an image of reasonableness,

credibility and professionalism

In the GNA Document:

• Anticipate the implementation demands of all

concessions: to the extent possible front-load the

agreement by getting provisions that don’t require

ongoing monitoring or enforcement; schedule company

concessions to come before community group concessions

• Strive to make agreements legally binding; consider

having agreements embedded in federal court consent

decrees or in permit conditions

• Establish a process to deal with future, unanticipated

issues (e.g., the sale or bankruptcy of the company);

assume that the company will eventually try to walk away

from the agreement

18

Table 5. Prerequisites to Using the GNA Approach Successfully:

Stage 3: Implementation of the Agreement

Sources of Leverage

• Best leverage is a strategically designed agreement (e.g.,

self-executing; timing of concessions is equal or front-

loaded in the community group’s favor; legally binding,

readily enforceable and transferable)

• Demonstrate a commitment to monitoring, oversight, and

follow-through; maintain contact with company and the

public regarding GNA compliance; be vigilant

• Publicize and celebrate achievements

Resources /

Strategies

• Budget sufficient funding, staff, and expertise to allow

ongoing monitoring and oversight; maintain public and

community group commitment/interest past GNA

negotiation (when initial enthusiasm fades)

• If necessary, consider relying upon an outside agency to

oversee or assist in implementation (e.g., a state agency

that adopted the GNA in a permit)

Other Advice /

Observations

• Have the company finance some of the community

group’s implementation costs

• Be prepared to endure a long, labor intensive process

• Constantly groom new leaders

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The overall conclusion and recommendation emerging from this study is that GNAs are a

process worth pursuing in the right circumstances. Those circumstances are varied, but at

a minimum, require a company with the potential to address community concerns while

maintaining economic viability, and a community group with sufficient leverage,

resources and skill to move through the often long process. While most of the GNAs we

identified were still working to fully achieve the GNA goals, the successes achieved to

date have clearly identified that GNAs, as a tool, can be very effective. Of course in each

case, the GNA tool needs to be compared to other options available. It is worth

remembering that many communities throughout the United States have found ways to

co-exist with industry without resorting to GNAs. National regulations regarding air and

water pollution, for example, are often sufficient to protect environmental resources and

public health. Additionally, many agencies can be relied upon to fight for community

protections. GNAs are not needed everywhere. But where this governmental safety net

is inadequate, GNAs can be a valuable addition to the toolbox of community activists.

Like all tools, the trick is simply to use it in the right circumstances and in the right

manner.

19

Two more specific recommendations are, first, to maintain in some form the GNA

network established in this project. The Northern Plains Resource Council (NPRC) has

established a web site and listserv dedicated to this purpose, building on and

supplementing the networking role so admirably carried for many years by Communities

for a Better Environment (California) and by dedicated individuals such as Sanford Lewis

and Denny Larson. Additionally, Northern Plains has produced a GNA handbook to

educate fellow community groups considering GNAs. These are wise and commendable

efforts that should be maintained. Secondly, we encourage the funding community to

consider grant-making to community groups with a defensible strategy and argument for

pursuing a GNA. Just as grants designed to support activism and litigation are ultimately

judged by funders on a return-on-investment calculus, so too should funding decisions

regarding GNAs—we do not advocate any special status or subsidy for GNAs.

Maximizing this return-on-investment suggests only funding GNAs where the

prerequisites for success can be met, and where both the funder and community group are

committed to the long-term GNA process.

20

21

APPENDIX A: SELECTED GNA LITERATURE

Adriatico, Marianne, The Good Neighbor Agreement: Environmental Excellence Without

Compromise, 5

Hastings W.-N.W. J. Envtl. L. & Pol’y 285 (Spring 1999).

Friends of the Earth Scotland, Love Thy Neighbour? The potential for Good Neighbour

Agreements in Scotland. June 2004. (See

http://www.foe-

scotland.org.uk/nation/gna_report.pdf)

Illsley, Barbara, Good Neighbour Agreements: the first step to environmental justice?,

Local Environment, vol. 7, no. 1, 69-79 (2002).

Lewis, Sanford, and Diane Henkels, Good Neighbor Agreements: A Tool for

Environmental and Social Justice,

Social Justice, vol. 23, no. 4 (Dec. 2, 1996).

Lewis, Sanford,

The Good Neighbor Handbook, 2

nd

ed., Apex Press (1993).

Lewis, Sanford, Precedents for Corporate-Community Compacts and Good Neighbor

Agreements, gnp.enviroweb.org/compxpr2.html (March 1996).

Peters, Alison, Cooperative Pollution Prevention: The Syntex Chemicals Agreement,

Pollution Prevention Review 23 (Spring 1996).

Siegel, Janet V., Negotiating For Environmental Justice: Turning Polluters Into "Good

Neighbors" Through Collaborative Bargaining,10

N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J. 147 (2002).

Additional literature and materials specific to the case studies are referenced at the end of

the case studies summaries in Appendix D.

22

APPENDIX B: GNA SURVEY

Community Group Participant Survey

Instructions: The questions below include both “check box” and “short answer” types. Please write

your answers in the space provided. If more space is needed, please attach additional sheets of paper

and indicate which question(s) you are responding to.

Note that the term “Company” in this questionnaire refers to the company with which the good neighbor

agreement (GNA) was negotiated.

Additional Documents. In addition to the survey, we are requesting copies of several documents, if

available. Providing these documents—especially the GNA itself—will significantly reduce the time and

effort required to complete the questionnaire. Please consult the cover letter to see which documents we

already have. The desired documents are:

o The signed GNA and any relevant supporting documentation (attachments, appendices, and/or

agreements drafted pursuant to a provision in the GNA).

o Published articles about your GNA or which prominently feature your GNA (e.g., newspaper,

newsletter, scientific journal, law review, editorials, etc.)

o Documentation of the GNA negotiation process itself (timeline, meeting minutes, progress

reports, correspondence between community groups and company, etc.)

o Implementation documents or reports (e.g., results of GNA-mandated environmental audits).

o Internal or external GNA evaluation studies or reports.

o Breakdown of costs (for your group and the company, if known) relating to any aspect of

negotiating and implementing the GNA.

o Environmental compliance data collected or received pursuant to the GNA.

o Material(s) describing your community group (size, goals, history, accomplishments, etc.).

We realize this is a lot of material to request, but this information is generally not available elsewhere.

We will pay for photocopying and postage charges in addition to the $50 payment to cover your time.

Your Contact Information

1. Your name:

_______

2. Your title/affiliation with community group: _______________________________

3. This is a ____ paid staff position ____ volunteer position.

4. Your mailing address: _________________________________________________

_________________________________________________

5. Your phone number: ( ) _______ - _________

6. Your fax number: ( ) _______ - _________

7. Your email address: _______________________________

Note: At the end of the survey, you will have the option of requesting anonymity.

23

General Information about your Community Group

8. Name of group:

____________

9. Mailing address (only if different than question # 4): ______________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

10. Web site: __________________________________________________________________

11. Year founded: __________

12. Number of paid staff: ________

13. Annual operating budget (general estimate): $ ______________

14. Major source(s) of funding (check all that apply):

___ individual & member contributions ..(approximate percentage of total budget: _____%)

___ government grants ………………… (approximate percentage of total budget: _____%)

___ foundation grants …………………. (approximate percentage of total budget: _____%)

___ the “Company” …………………….. (approximate percentage of total budget: _____%)

___ other ………………………………. (approximate percentage of total budget: _____%)

General Characteristics of the Company and the Community-Company Relationship

15. Approximately what year did “the Company” begin operations in your community? __________

16. Approximately how many local residents does “the Company” employ? ______________

17. On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is “the Company” to the local economy? (1 = not important; 5

= moderately important; 10 = extremely important). ____________

18. On the same scale of 1 of 10, how important is the sector represented by “the Company” (e.g.,

mining, petrochemicals) to the local economy? __________________

19. At the time of GNA negotiation, “the Company” was: (check all that apply)

___ profitable (i.e., in “good” financial health)

___ expanding ___stable in size ___shrinking

___ seeking financing

___ privately owned ___ publicly traded ___don’t know

___ concerned about public opinion

___ perceived publicly as committed to environmental concerns

20. Is “the Company” currently a subsidiary of another company? ___ yes (name:________________ )

___no ___don’t know

21. Who is the appropriate contact person(s) at “the Company” regarding the GNA? (Please provide

one or more names, with complete contact information.) __________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________

24

Incidents/Events Which Led to the Negotiation of the GNA

22. Which of the following types of issues prompted community concern about “the Company”?

(Check all that apply. If more than one category is selected, please number them in order of

significance; 1 = most significant, 2 = second most significant, etc.)