www.hks.harvard.edu

Creating Birds of Similar

Feathers

Faculty Research Working Paper Series

Hunter Gehlbach

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Maureen E. Brinkworth

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Aaron M. King

Stanford University

Laura M. Hsu

Merrimack College

Joe McIntyre

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Todd Rogers

Harvard Kennedy School

April 2015

RWP15-017

Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at:

https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/workingpapers/Index.aspx

The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of

the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of

Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not

undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit

feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright

belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only.

Creating birds

of similar feathers

by Hunter Gehlbach, Maureen E. Brinkworth, Aaron M. King, Laura M. Hsu, Joe McIntyre, Todd Rogers

Keywords: Adolescence, Brief interventions, Field experiment, Matching, Motivation, Similarity, Social Processes/

Development, Teacher-student relationships.

Leveraging similarity to improve teacher-

student relationships and academic

achievement

Abstract

When people perceive themselves as similar to others, greater liking and closer relationships typically result.

In the first randomized field experiment that leverages actual similarities to improve real-world relationships,

we examined the affiliations between 315 ninth grade students and their 25 teachers. Students in the

treatment condition received feedback on five similarities that they shared with their teachers; each teacher

received parallel feedback regarding about half of his/her ninth grade students. Five weeks after our

intervention, those in the treatment conditions perceived greater similarity with their counterparts.

Furthermore, when teachers received feedback about their similarities with specific students, they

perceived better relationships with those students, and those students earned higher course grades.

Exploratory analyses suggest that these effects are concentrated within relationships between teachers

and their “underserved” students. This brief intervention appears to close the achievement gap at this

school by over 60%.

Reference:! Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., Hsu, L., King, A., McIntyre, J., & Rogers, T. (in press).

Creating birds of similar feathers:! Leveraging similarity to improve teacher-student relationships and

academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology.

Humans foster social connections with others as a

fundamental, intrinsic social motivation – we are

hard-wired to be social animals (Lieberman, 2013;

Ryan & Deci, 2000). Those who more successfully

relate to others experience a broad constellation of

positive outcomes ranging from greater happiness

(Gilbert, 2006) to superior health (Taylor et al.,

2004). Children who thrive typically cultivate

positive relationships with parents, peers, and

teachers (Wentzel, 1998). Even for adolescents,

achieving positive teacher-student relationships

(TSRs) is an important outcome in its own right

and may catalyze important downstream benefits

(Eccles et al., 1993).

Thus, for those who study positive youth

development, schooling, and social motivation

(e.g., Bronk, 2012; Pintrich, 2003) the topic of

improving TSRs sparks tremendous interest. One

promising approach might leverage individuals’

perceptions of similarity as a means to promote a

sense of relatedness. Numerous basic social

psychological texts underscore some version of

the basic message that “likeness begets

liking” (Myers, 2015, p. 330). Similarity along

various dimensions (style of dress, background,

interests, personality traits, hobbies, attitudes, etc.)

connects to a wide array of relationship-related

outcomes (such as attraction, liking, compliance,

and prosocial behavior) in scores of studies

(Cialdini, 2009; Montoya, Horton, & Kirchner,

2008).

The theory behind the promise of this approach is

that interacting with similar others supports one’s

sense of self, one’s values, and one’s core identity

(Montoya et al., 2008; Myers, 2015). In other

words, as an individual interacts with similar

others, she reaps positive reinforcement in the

form of validation. For instance, imagine a 9th

grade student enrolling in high school in a new

town. As she encounters peers who also value

religion, enjoy sports, participate in math club, and

aspire to attend college, she learns that her values

and beliefs are socially acceptable within her new

community. Continuing to affiliate with these

individuals will reinforce a perception that her

values and beliefs have merit. Conversely, her

peers who eschew religion, think sports are silly,

ridicule math club, and see no point in college will

cast doubt on the values and beliefs that lie at the

core of her identity. Spending time with these

students will not be reinforcing. In this way,

similarity acts as a powerfully self-affirming

motivator (Brady et al., this issue) in the context of

friendships and close relationships.

Unfortunately, a fundamental problem arises in

using similarity to improve relationships: people

either share something in common or they do not.

Thus, scholars can develop experimental

manipulations of similarities but these interventions

typically rely upon fictitious similarities (e.g., Burger,

Messian, Patel, del Prado, & Anderson, 2004;

Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000). While these studies

enable causal inferences to be made, the fictitious

nature of the similarities minimizes their utility for

real-world interventions. On the other hand,

numerous correlational studies have identified real

similarities between individuals in real relationships

and have shown that these similarities correspond

with improved relationship outcomes (e.g., Chen,

Luo, Yue, Xu, & Zhaoyang, 2009; Gonzaga,

Campos, & Bradbury, 2007; Ireland et al., 2011).

However, the correlational nature of these studies

precludes causal inferences from being made.

Thus, how scholars might successfully leverage

real similarities to improve real-world relationships,

such as TSRs, remains a vexing challenge.

In this study, we test the effects of an intervention

that potentially mitigates these trade-offs.

Specifically, we experimentally manipulate

perceptions of veridical similarities as a means to

try and improve TSRs between ninth graders and

their teachers. In addition to examining TSRs as a

key outcome, we note that these relationships

have shown robust associations with

consequential student outcomes (McLaughlin &

Clarke, 2010). Thus, we also test whether the

intervention affects students’ classroom grades.

To our knowledge, this is the first experimental

2

study to use actual similarities as a means to

improving real, ongoing relationships.

Similarity and Relationships

Of the research connecting similarity and

interpersonal relationships, two main types of

studies proliferate: those that have fabricated

similarities for the sake of experimental

manipulations and those that have investigated

actual similarities. Both types of studies have

enhanced scientific understanding of the

importance and potency of similarity in

relationships. Across both the experimental and

correlational approaches, two notable themes

emerge.

First, the content of the similarities associated with

improved relationship outcomes covers an

impressively disparate array of topics. For

example, scholars have experimentally

manipulated the similarity of names to boost liking

and compliance. One researcher bolstered return

rates on a questionnaire by using names on a

cover letter that were similar to respondents’ own

names (Garner, 2005). In a series of primarily

correlational studies, Mackinnon, Jordan, and

Wilson (2011) found that students who are

physically similar to one another (e.g., both

wearing glasses) will tend to sit next to one

another in class. Using both experimental and

correlational approaches, Boer et al. (2011) found

that shared music preferences helped foster closer

social bonds between people.

Although few scholars have explored the idea of

using similarities to improve relationships in

education, some have examined whether students

perform better academically when their teacher

shares their ethnicity. For instance, Dee (2004)

found significant positive effects on test score

outcomes for black students who were assigned

to black teachers and for white students who were

assigned to white teachers. Although he does not

examine TSRs, he does hypothesize that trust and

role-modeling may be crucial mechanisms in

explaining his findings.

Second, even the most trivial similarities can lead

to positive sentiments toward another person.

Laboratory experiments informing participants that

they and another participant share: a preference

for Klee versus Kandinsky paintings (Ames, 2004),

the tendency to over- or under-estimate the

number of dots on a computer screen (Galinsky &

Moskowitz, 2000), or purported similarity in

fingerprint patterns (Burger et al., 2004), have all

enhanced relationship-related outcomes.

Correlational studies show comparably surprising

findings. For example, people who have similar

initials are disproportionately likely to get married

(Jones, Pelham, Carvallo, & Mirenberg, 2004).

Despite their contributions, these two approaches

to studying the connections between similarity and

relationships leave two important gaps in our

knowledge. First, this work leaves open the

crucial scientific question of whether real

similarities cause improved outcomes in real

relationships. Certainly, the preponderance of this

experimental and correlational evidence,

generalized across so many types of similarities –

including ones that seem especially unimportant –

suggests that this causal association should exist.

However, without direct experimental evidence,

some doubt remains.

A second gap in our knowledge is particularly

salient for educational practitioners. Without some

way to leverage real similarities between individuals

within a classroom, the associations between

similarity and relationship outcomes have limited

practical applications. Car salespeople may be

well-served by suggesting that they too enjoy

camping, golf, or tennis if they notice tents, clubs,

or rackets in the trunk of your car (Cialdini, 2009).

However, teachers who lie about what they share

in common with individual students will likely be

found out over the course of an ongoing

relationship (to say nothing of the ethically dubious

3

nature of this tactic). One could argue that

teachers might leverage similarity by learning what

students have in common with each other and

assigning them to collaborative groups with like-

minded classmates. However, it seems important

for schools to socialize students to work effectively

with those from different backgrounds. In sum, as

compelling and robust as the similarity-relationship

research is, important scientific and applied gaps

plague our understanding of these associations.

Teacher-Student Relationships

and Student Outcomes

In addition to healthy relationships as an important

outcome in their own right (Leary, 2010), TSRs

matter because they are associated with a broad

array of valued student outcomes including:

academic achievement, affect, behavior, and

motivation. As McCombs (2014) concludes from a

series of studies she conducted, “What counts

and what leads to positive growth and

development from pre-kindergarten to Grade 12

and beyond is caring relationships and supportive

learning rigour” (p. 264).

Many studies have shown that students with

better TSRs tend to achieve more highly in school

(Cornelius-White, 2007; Roorda, Koomen, Split, &

Oort, 2011). For example, Wentzel (2002) found

that middle-school students’ perceptions of their

teachers on relational dimensions such as fairness

and holding high expectations predicted students’

end-of-year grades. Estimated effect sizes of

TSRs on achievement range from r = .13 to .28

1

for positive relationships at the secondary level

(Roorda et al., 2011).

With respect to students’ affect towards school,

students in classes with more supportive middle

school teachers have more positive attitudes

toward school (Roeser, Midgley, & Urdan, 1996;

Ryan, Stiller, & Lynch, 1994) and their subject

matter (Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989).

Conversely, middle school students who lack a

bond with their teacher are more likely to

disengage or feel alienated from school (Murdock,

1999). Cornelius-White’s (2007) meta-analysis

showed that TSRs were correlated with students’

satisfaction with school (r = .44).

2

Associations between TSRs and students’

behavior include findings that middle school

students more willingly pay attention in class when

they think their teacher cares more (Wentzel,

1997). On the other hand, adolescents’ who

perceived more disinterest and/or criticism from

their teachers were more likely to cause discipline

problems (Murdock, 1999). Cornelius-White’s

(2007) findings show that more positive student

perceptions of their TSRs corresponded with

increased student participation (r = .55) and

attendance (r = .25), and decreased disruptive

behavior (r = .25).

Studies of TSRs and student motivation follow

similar patterns. Adolescents’ perceptions of

teacher support and caring predict student effort

as reported by both teachers (Goodenow, 1993;

Murdock & Miller, 2003) and students (Sakiz,

Pape, & Hoy, 2012; Wentzel, 1997). Meta-

analyses (Cornelius-White, 2007; Roorda et al.,

2011) show that TSRs are associated with

motivation (r = .32) and secondary school

engagement (r = .30 to .45).

Of this array of important outcomes, we chose to

focus on students’ classroom grades. Among the

associations between TSRs and these outcomes,

we felt grades were (arguably) the most

consequential for students’ futures – potentially

affecting advancement/retention decisions,

tracking, graduation, college placement, and

additional, important outcomes.

Scientific Context of the Study

In striving to contribute to the scientific theories

linking similarity and relationships, we structured

1

This range represents

the lower and upper

bounds of the

confidence intervals

across both the fixed

and random effects

models the authors

used.

2

Cornelius-White

(2007) does not report

elementary and

secondary student

results separately for his

outcomes.

4

the study to learn whether the causal associations

between similarity and relationships found in

laboratory studies generalized to real, ongoing

relationships. Furthermore, if successful, our

intervention would have important applications for

classrooms. Specifically, it would offer a tangible

example of how similarities might be leveraged to

actually improve relationships in the classroom.

Simultaneously, we hoped to evaluate the effects

of our intervention as rigorously as possible in a

naturalistic setting and to err on the side of being

conservative in the inferences we made from our

data.

We evaluated our intervention using a 2 X 2 design

and focusing on a single class period. Through

this design, each individual within every teacher-

student dyad was randomly assigned to receive

feedback (or not) from a “get-to-know-you” survey.

Specifically, students were randomly assigned to

either learn what they had in common with one of

their teachers (i.e., students in the “Student

Treatment” group), or not learn about similarities

with their teacher (i.e., students in the “Student

Control” group). Teachers found out what they

had in common with about half of their students in

the focal class (i.e., students in the “Teacher

Treatment” group) but not with the other half (i.e.,

students in the “Teacher Control” group). Thus, all

randomization occurred at the student level.

In the spirit of recent recommendations (Cumming,

2014; Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011), we

identified six “pre-specified hypotheses” prior to

analyzing our data. Specifically, we expected that

students in the Student Treatment group would (1)

perceive themselves as more similar to their

teachers and (2) report a more positive TSR as

compared to those in the Student Control group.

For students in the Teacher Treatment, we

expected that, (3) their teacher would perceive

these students as more similar, (4) their teacher

would rate their TSR more positively, and the

students’ (5) mid-quarter grade, and (6) final

quarter grade would be higher than students in the

Teacher Control group. As described in the

Statement of Transparency in our supplemental

online materials we also collected additional

variables and conducted further analyses that we

treat as exploratory.

These main hypotheses reflect an underlying logic

that by focusing teachers’ and students’ attention

on what they have in common, we will change

their perceptions of how similar they are to one

another. Congruent with the aforementioned

research on similarity, we expect these changed

perceptions will lead to more positive relationships

between teachers and students. In other words,

the core social psychological theory that we are

reinforced by our social interactions with similar

others (Montoya et al., 2008), will generalize to the

educational setting we studied. These more

positive relationships, in turn, will cause other

downstream benefits for students.

Two explanatory notes about these hypotheses

are in order. First, we hypothesized that students’

grades would be affected by the Teacher

Treatment (but not the Student Treatment) based

on previous correlational work. Brinkworth,

McIntyre, Harris, and Gehlbach (manuscript under

review) showed that when accounting for both

teachers’ and students’ perceptions of their TSR,

the teachers’ perceptions (but not students’

perceptions) of the TSR are associated with

students’ grades. Second, similar studies of brief

interventions that have impacted students’ grades

have found that the effect of the intervention was

concentrated within a sub-population of students,

such as African-American students (Cohen,

Garcia, Apfel, & Master, 2006; Walton & Cohen,

2011), Latino students (Sherman et al., 2013), or

low self-efficacy students (Hulleman &

Harackiewicz, 2009). However, in the absence of

information about which sub-groups might react

most positively to the intervention, we made no

predictions about potential sub-group effects of

the intervention.

5

Methods

Participants

We conducted the study at a large, suburban high

school in the southwestern United States. We

focused on ninth graders because they were just

transitioning to high school and might particularly

benefit from connecting with an adult in a school

where they did not know any authority figures.

The students in our final sample (N = 315) were

60% female, 51% White, 19% Latino, 11% Asian,

6% Black, and 10% reporting multiple categories

or “other.” These proportions of different races/

ethnicities are similar to the school as a whole

(54% White, 20% Latino, 13% Asian, and 10%

Black). These students were mostly native English

speakers (81%) and came from families where

college graduation represented the median

educational level of the mothers and fathers

(though the range included mothers and fathers

who had not attended elementary school to those

who completed graduate school).

The teachers in our sample (N = 25) were 52%

male, 80% White, and 92% native English

speakers. These 25 teachers were part of a

faculty of 170, 41 of whom taught 9th graders.

The mean age of the teachers was 47.5 years old

(sd = 10.42), and the mean years of experience

was 18.0 (sd = 9.5). Most teachers (72%) had

completed a graduate degree and came from

families where 1 year of college represented the

median educational level for both their mothers

and fathers (though the range extended from

those completing fourth grade to those who

completed graduate school). Both teachers and

students were blind to the purpose of the study.

Measures

Our main measures were borrowed from

Gehlbach, Brinkworth, and Harris (2012).

Students’ perceptions of their degree of similarity

to their teachers were assessed through a six-item

scale (α = .88), which included items such as

“How similar do you think your personality is

compared to your teacher's?” Students’

perceptions of their TSR were measured with a

nine-item scale (α = .90) that asked students to

evaluate their overall relationship with their

teachers, e.g., “How much do you enjoy learning

from <teacher's name>?” To minimize the burden

on teachers, we asked them a single item to

assess their perceptions of similarity to each

student, “Overall, how similar do you think you and

<student's name> are?” However, they did

complete the full parallel nine-item teacher-form of

the TSR scale (α = .86 for teachers; see the online

appendix for a complete listing of these scales).

We collected mid-quarter and final quarter grades

from student records. Because teachers at this

high school have autonomy to decide on the most

appropriate way to grade students, this measure

represents a combination of homework, quizzes,

and other assessments depending upon teachers’

individual approaches and the subject matter they

teach.

Our exploratory analyses employed additional

measures. Teachers rated the amount that they

interacted with their students by answering,

“Compared to your average student, how much

have you interacted with <student's name> this

marking period?” We also collected attendance

and tardiness data and (eventually) end-of-

semester grades from school records. These

measures are listed in the supplementary online

materials.

Procedure

The study unfolded over the course of the first

marking period at the school. Just prior to the

beginning of the school year, the principal helped

our research team recruit as many ninth grade

teachers as were interested in participating. In

turn, during the first week of school these 27

consenting teachers helped us collect consent

forms from their students. Throughout the

following week of school, these students and

teachers visited their computer lab and completed

the initial get-to-know-you survey. We mailed our

6

feedback forms to the school by the middle of the

third week of classes. Students (N = 315) and 24

teachers then completed these forms over the

course of the next two weeks. An additional

teacher submitted her feedback sheet late (though

her students completed their sheets on time); this

teacher and her students were retained in the

sample. Two teachers and their classes never

completed the feedback forms, thereby reducing

the final sample size to 315 students and 25

teachers. Mid-quarter progress grades were

finalized at the end of the fifth week of classes.

During the eighth and ninth weeks of classes,

students and teachers took the follow-up survey.

(Because teachers were allowed to take the survey

on their own time, some teachers completed the

follow up survey up to one month later). The

quarter concluded at the end of the tenth week of

classes.

Students and teachers took the 28 item get-to-

know-you survey during their first period class.

The survey asked teachers and students what

they thought the most important quality in a friend

was, which class format is best for student

learning, what they would do if the principal

announced that they had a day off, which foreign

languages they spoke, and so on (See Figure 1).

From these surveys we composed the feedback

sheets that comprised the core of the intervention.

On these feedback sheets, we listed either five

things students had in common with their teacher

(in the Student Treatment group

3

) or five

commonalities the students shared with students

at a school in another state (in the Student Control

group). Each teacher received five items that they

had in common with each student who was

among those randomly selected into the Teacher

Treatment group (i.e., half of the participating

students from the teacher’s first period class).

Teachers were informed that in the interest of

providing prompt feedback, we could not provide

reports on their remaining first-period students (the

Teacher Control group). The five similarities were

chosen based on an approximate rank ordering of

the similarities that had seemed to be most

important for generating perceptions of similarity

from the pilot test in the previous year (see the

Statement of Transparency for more on the pilot

3

We generated five

similarities for all but one

teacher-student pair – a

dyad where only four

similarities were present

after matching their get

to know you surveys.

This dyad was retained

in our analyses.

Figure 1: Screen shot of

the get-to-know-you survey.

7

test). Students and teachers responded to a

series of brief questions on their feedback sheets

such as, “Looking over the five things you have in

common, please circle the one that is most

surprising to you.” Our hope was that by

completing these questions on their feedback

sheets, students and teachers would more deeply

consider and better remember their points of

commonality with one another. Current copies of

the measures and materials are available from the

first author upon request.

Results and Discussion

Pre-specified Hypotheses

As detailed in our “Statement of

Transparency” (see the supplemental online

materials), we pre-specified six hypotheses

(Cumming, 2014). Specifically, we anticipated

that (as compared to those in the Student Control

group) students in the Student Treatment group

(1) would perceive more similarities and (2) a more

positive TSR with their teacher. As compared to

those in the Teacher Control group, we

hypothesized that teachers would perceive

students in the Teacher Treatment group as (3)

being more similar, and (4) teachers would

develop a more positive TSR with these students.

Finally, we expected that the students in the

Teacher Treatment group would earn (5) higher

mid-quarter and (6) higher end-of-quarter grades

than their counterparts in the Teacher Control

group.

As described in the Statement of Transparency,

we expected to test these hypotheses through a

combination of multi-level modeling (i.e.,

hypotheses 3, 5, and 6 when the outcome was a

single item) and multi-level structural equation

modeling (i.e., hypotheses 1, 2, and 4 when the

outcome was a latent variable). However, our

statistical consultant advised us that the number

of teachers (i.e., level 2 clusters) was inadequate

for Mplus to provide trustworthy estimates for the

models using latent variables. Our models for

latent variables had more parameters to be

estimated than clusters, making multilevel SEM

impossible. Due to this nested structure of our

data, we relied on mean- and variance-adjusted

weighted least squares for complex survey data

(WLSMV-complex) estimation, using the

CLUSTER option in Mplus. WLSMV-complex,

which uses a variance correction procedure to

account for clustered data, provides corrected

standard errors, confidence intervals, and

coverage (Asparouhov, 2005). We used full

information maximum likelihood (FIML) to address

missing data. The maximum proportion of missing

data for any variable was .012. However, we

used Mplus’ robust standard error approach when

our outcomes were latent. To evaluate each

hypothesis, we regressed the outcome on the

condition as described above. Because random

assignment produced equivalent groups between

both treatment groups and their respective control

groups on key demographic characteristics

(specifically gender, race, English language status,

and parents’ educational level), no covariates

were used in these analyses. Consistent with

Cumming’s (2014) recommendation, we evaluated

our hypotheses using 95% confidence intervals to

emphasize the range of plausible values for the

treatment effect rather than relying on p-values. In

8

addition, we report standardized β to provide an

estimate of effect size (except for grade-related

outcomes where the original 0 to 4.0 scale

provides meaningful equivalents of an F through an

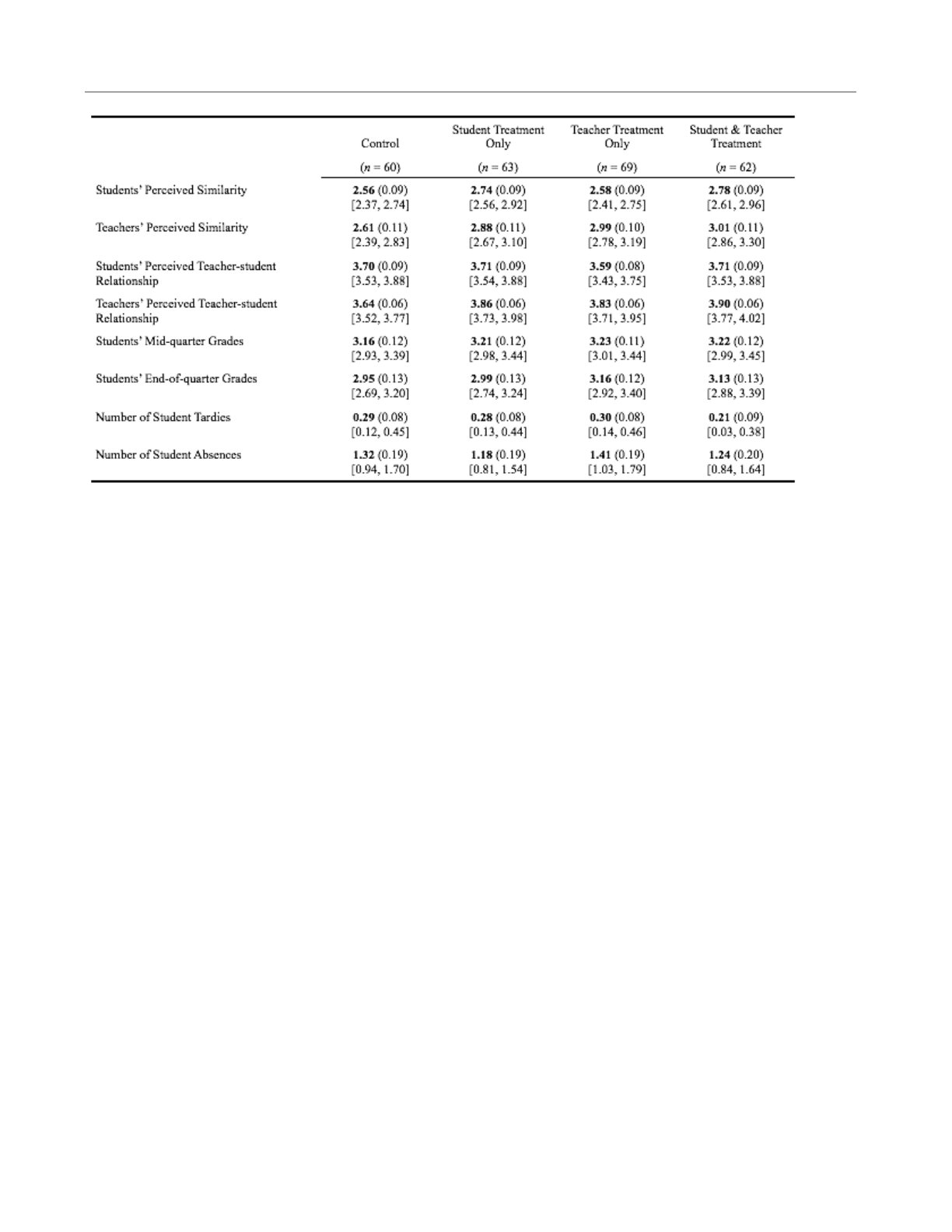

A). We present descriptive statistics in Table 1.

Our results are congruent with the similarity

hypotheses (i.e., hypotheses 1 and 3). Each

treatment made students and teachers feel more

similar to one another by the end of the marking

period ( β = 0.33, SE = 0.12, CI: 0.10, 0.56 for

students; and β = 0.33, SE = 0.11, CI: 0.11, 0.55

for teachers). In other words, we retain the null-

hypothesis that the true standardized treatment

effect fell within the range from .11 and .55 (and

between .10 and .56 for students), while bearing in

mind that the most plausible values are those

closest to .33.

By contrast, the students perceived their TSRs to

be relatively similar regardless of the condition to

which they were assigned ( β = 0.09, SE = 0.14,

CI: -0.18, 0.36). In other words, we found minimal

support for hypothesis 2. Within the Teacher

Treatment, teachers perceived a more positive

relationship with these students ( β = 0.21, SE =

0.11, CI: 0.00, 0.42). For students in the Teacher

Condition, we found no compelling support for an

Variable Name

Mean

sd

Min.

Max.

Pearson Correlations

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1) Students' similarity

2.68

0.73

1.00

4.17

--

2) Teachers’ similarity

2.90

0.91

1.00

5.00

.13

--

3) Students’ TSR

3.68

0.68

1.00

5.00

.69

.18

--

4) Teachers' TSR

3.85

0.55

2.22

5.00

.29

.63

.32

--

5) Mid-quarter Grade

3.26

0.99

0.00

4.00

.34

.23

.35

.41

--

6) End-of-quarter

Grade

3.16

1.10

0.00

4.00

.30

.18

.35

.43

.76

--

7) Semester grade

2.79

1.11

0.00

4.00

.24

.31

.28

.47

.67

.79

--

8) Tardies

0.26

0.66

0.00

9.00

-.13

-.01

-.08

-.05

-.20

-.22

-.13

--

9) Absences

1.29

1.61

0.00

5.00

-.15

-.08

-.06

-.16

-.20

-.15

-.10

.15

--

10) Teacher reported

interactions

4.74

1.10

2.00

7.00

.21

.37

.17

.46

.16

.22

.21

-.11

-.10

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for key variables in the

study (unadjusted mean, sd, and Pearson (r)

correlations).

Notes:

1) Ns ranged from 275-362.

2) Correlations are unadjusted for the nesting of students within classrooms.

3) Approximate significance levels are as follows: for |rs| ranging from 0 to .12, p = ns; for |rs| ranging

from .13 to .16, p < .05; for |rs| ranging from .17 to .20, p < .01; for |rs| .21 and greater, p < .001.

9

effect on mid-quarter grades ( β = 0.04, SE =

0.10, CI: -0.15, 0.23). Although the confidence

interval does include 0, our point estimate and the

range of plausible responses suggests that

students in the Teacher Condition probably earned

higher end-of-quarter grades ( β = 0.21, SE =

0.11, CI: 0.00, 0.43). Figures 1-4 in the

supplementary online materials show how the

unadjusted means are distributed when the

Teacher and Student Conditions are separated

into their four unique groupings of the 2 X 2

design.

The first pair of findings shows that the intervention

successfully enhanced teachers’ and students’

perceptions of similarity. On the one hand, the

effects do not seem particularly potent – perhaps

reflecting only a mildly-to-moderately strong

intervention. On the other hand, students

processed their feedback sheets for approximately

fifteen minutes before handing them back in, and

yet, still perceived themselves as being more

similar to their teacher over a month later.

Teachers presumably spent even less time on

each feedback sheet given that most teachers had

several to complete. Thus, while one might argue

that the effects of the intervention were weak, this

interpretation should be calibrated against the

brevity of the intervention and the amount of time

that elapsed before the outcomes were collected

(Cumming, 2014).

Although the intervention appeared to improve

teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with

students, we do not find compelling evidence that

the intervention improved TSRs from students’

perspectives. To the extent that this result reflects

a genuine difference in the effect of the

intervention, one plausible explanation is that

teachers view part of their role as needing to foster

positive relationships with students. Thus, they are

motivated to perceive students whom they view as

similar in a positive light. By contrast, students

may not feel any particular obligation to form a

positive relationship with their teachers. Learning

that they share common ground with their teacher

may not change their perception of their teacher

because 9th grade students have no particular

motivation to cultivate this social relationship.

Our findings for students’ academic achievement

seem paradoxical: the intervention appears to

show positive effects at the end of the quarter after

finding no effects half-way through the marking

period. However, we think this apparent paradox

results from a logistical issue rather than a finding

of substantive interest. In an unfortunate

oversight, we finalized our pre-specified

hypotheses prior to reviewing the timing of each

key aspect of the study. Although the direction of

the estimate for students’ mid-quarter grades is

the same as the end-of-quarter grades, we

suspect that the intervention occurred too close to

teachers’ grade-submission deadline to have a

meaningful effect in most classes. In other words,

students may not have had a sufficient opportunity

to do enough graded work between the time that

they (and their teachers) completed their feedback

sheets and the date that mid-quarter grades were

due. As a result, we do not discuss this outcome

further. Students’ performance on their final

quarter grades, by contrast, suggests that the

intervention probably caused students’ grades to

increase. Our point estimate of this increase

corresponds to a little less than a fifth of a letter

grade.

To better understand our initial pattern of results,

we examined whether our intervention might have

had differential effects on different sub-populations

of students. By fitting a series of multi-level

models (for observed outcomes) and models with

robust standard errors (for latent outcomes) in

MPlus, we conducted a series of exploratory

analyses on different student subgroups.

Exploratory Analyses

A number of previous studies that employ relatively

brief, social psychological interventions (Cohen et

10

al., 2006; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009;

Sherman et al., 2013; Walton & Cohen, 2011)

suggest that certain subgroups of students often

benefit disproportionately from the interventions.

Specifically, we thought that the school might

serve some students better than others, or that

there might be a dominant culture at the school

that was more inclusive of some students than

others. After speaking with the principal about this

possibility, he suggested that the White and Asian

students were typically well-served by the school,

while Black and Latino students typically faced

more challenging circumstances at home, at

school, and throughout their community. Thus, we

re-examined our data by analyzing the White and

Asian students as a separate group from the

remaining “underserved” students. Because these

are exploratory analyses, we do not retain the

same level of confidence in these findings as our

pre-specified hypotheses. However, we argue that

these results are likely to be instructive for

generating future hypotheses (Cumming, 2014).

When fitting our models, we found little evidence

for any effects of the intervention on the White and

Asian students. We find no particularly compelling

evidence that White and Asian students in the

Student Treatment group perceived different levels

of similarity with their teachers ( β = 0.17, SE =

0.15, CI: -0.13, 0.46) or felt their relationships to

be different ( β= -0.12, SE = 0.17, CI: -0.46, 0.21)

as compared to those in the Student Control

group. We find a comparable lack of evidence that

the intervention affected teachers’ perceptions of

their similarity to their White and Asian students ( β

= 0.11, SE = 0.16, CI: -0.20, 0.41) and teachers’

perceptions of their relationships with these

students ( β = 0.00, SE = 0.15, CI: -0.29, 0.29).

Finally, we find no evidence that the intervention

affected White and Asian students’ end-of-quarter

grades ( β = -0.01, SE = 0.15, CI: -0.29, 0.27).

For the underserved students, the story differed.

Underserved students who received feedback

about commonalities with their teachers felt much

more similar to their teachers ( β = 0.56, SE =

0.20, CI: 0.18, 0.96) than their counterparts who

did not receive this feedback. It was less clear

whether these students felt more positive about

their relationships with their teachers ( β = 0.39,

SE = 0.24, CI: -0.08, 0.86), though the estimated

effect size was moderate and in the expected

direction. When teachers received feedback about

similarities with their underserved students, they

perceived greater levels of similarity with those

students as compared to their control

counterparts ( β = 0.56, SE = 0.24, CI: 0.08,

1.04). Similar to the underserved students, it was

unclear whether teachers in the treatment group

felt more positive about their TSRs with these

students ( β= 0.43, SE = 0.27, CI: -0.11, 0.96).

Finally, we found some evidence that underserved

students’ end-of-quarter grades ( β = 0.36, SE =

0.20, CI: -0.04, 0.75) were most likely higher when

their teacher received feedback about their

commonalities as compared to students in the

Teacher Control condition, although the

confidence interval does include 0. As depicted in

Figure 2, the point estimate for this difference

translates into about .4 of a letter grade on a 4.0

scale and corresponds to the difference between a

C+/B- versus a B.

Assuming the point estimate approximates the

true value of the treatment effect, these effects on

grades are substantial. If we compare the White

and Asian students with the underserved students

in Figure 2, we can estimate the achievement gap

between well-served and underserved ninth

graders at this school to be approximately .6 of a

letter grade. When teachers learned about the

similarities that they shared with their underserved

students, the achievement gap was reduced by

two-thirds to only .2 of a letter grade. This

reduction is in line with other relatively brief

interventions that have closed the achievement

gap. For example, Cohen et al. (2006) report a

40% closure with an even briefer intervention;

Walton and Cohen (2011) report a 52% to 79%

11

reduction (depending upon the time period

examined) from their more intensive intervention.

Given the potential importance of these

differences, we carried out two final sets of

analyses. First, in order to see the extent to which

these results persisted over time, we obtained

students’ grades in their focal class for the full

semester. These analyses showed that the effects

of the intervention on the underserved students

trended in the same direction as the results for

students’ end-of-quarter grades ( β = 0.33, SE =

0.22, CI: -0.11, 0.77).

Figure 2: Mean differences and 95% confidence intervals for underserved students by

Teacher Condition in teachers’ perceptions of similarity, perception of their teacher-student

relationships (TSR), and students’ end-of-quarter grades in their focal class. Means for

White and Asian students are presented for comparison.

Notes: The 65% reduction in the

achievement gap shown in the

right-hand triad of bars

corresponds to the difference

between less than a B- to a B.

12

Second, in anticipation of trying to understand

more about the effect of the intervention, we

tested whether the intervention appeared to affect

other variables we had collected. In particular, we

examined attendance and tardiness data from

school records and how much teachers reported

interacting with each student as compared to the

average student. The results from these analyses

suggest that the intervention did not affect

students’ attendance in their focal class (see

Figures 4a and 4b in the supplemental online

materials). However, the previously noted

subgroup differences emerged in how much

teachers reported interacting with their students.

Specifically, we found no differences by condition

in how much teachers interacted with their White

and Asian students ( β = -0.13, SE = 0.16, CI:

-0.43, 0.17), but they interacted more with those

underserved students who were in the Teacher

Treatment Condition ( β = 0.43, SE = 0.16, CI:

0.12, 0.74).

Conclusion

Our study builds on the robust social

psychological research showing that similarity

fosters liking and more positive relationships. By

experimentally manipulating teachers’ and

students’ perceptions of actual similarities, our

study allows for causal inferences to be made

about the effects of similarity on real-world,

ongoing relationships. Results from our pre-

specified hypotheses suggest that the intervention

alters students’ and teachers’ perceptions of how

much they have in common, benefits TSRs (at

least from the teacher’s perspective), and likely

bolsters students’ classroom grades.

A primary theoretical contribution of this work is

the demonstration that the causal association

between similarity and relationship outcomes

found in numerous laboratory studies can

generalize to real-life relationships. However, the

potential of this intervention to generate broad

impact in classrooms is every bit as important. If

this approach of connecting students and

teachers fosters more positive TSRs (even if the

effects are primarily teachers’ perceptions of their

relationships with certain students), it represents a

relatively quick and easy way to improve an

important outcome. In addition, if future studies

replicate the narrowing of the achievement gap

found in this sample, this intervention would be a

particularly “scaleable” from a policy perspective.

Like any study, ours includes a number of

limitations that warrant readers’ attention. First,

the implementation of the various steps of the

intervention was imperfect (e.g., a teacher failing to

complete the feedback sheets on time, two other

teachers responding to the final survey late, etc.).

We hope that future studies can remedy these

problems and design systems to administer the

intervention consistently. However, we also note

that implementation of all manner of interventions

(new curricula, disciplinary systems, web portals

for parents, and so on) in schools tend to be

imperfect. The fact that our intervention was

largely effective despite the flaws in execution is an

important footnote for practitioners.

Second, our analyses (particularly the exploratory

analyses) lacked the statistical power we desired.

This caused us to shift to a different statistical

approach than the one we had originally planned

in our statement of transparency. Our statistical

consultant also noted that the multi-level model

and clustered standard error approaches we

employed, may still result in too many Type-I errors

when the number of clusters is small, i.e., fewer

than 50 (see, for example, Bertrand, Duflo, &

Mullainathan, 2004; Donald & Lang, 2007). To

address this potential limitation, we employed a

wild cluster bootstrap-t (Cameron, Gelbach, &

Miller, 2008). As shown in Table 1 in the appendix,

our findings using that approach were generally

consistent with those we obtained from our multi-

level model and robust standard error models.

Particularly given the emerging hypothesis that the

effectiveness of the intervention may be localized

13

to underserved students, future replications should

try to obtain substantially larger samples with more

clusters across a variety of schools to better

evaluate this possibility.

Third, our exploratory findings suggested

differences between well-served (White and Asian)

and underserved (primarily Black and Latino)

students. However, this division of students may

mask a more accurate understanding of what

moderates the effects of the intervention. For

example, we lacked a reasonable measure of

socio-economic status in our data set. Given the

correspondence between race and socio-

economic status in this country, we may have

actually detected a moderating effect of socio-

economic status that our data masked as a race-

based effect. Thus, future studies that can collect

a wider array of more precise demographic

measures would also be particularly beneficial.

Fourth, the underlying logic of our study describes

a story of mediation. Specifically, the effect of our

similarity intervention on students’ grades may be

mediated by teachers’ perceptions of their

relationships with students. However, recent work

has sharpened our understanding of mediation.

Proving mediation is a difficult and ongoing journey

rather than a succinct set of equations (Bullock,

Green, & Ha, 2010) that establish a particular

variable as a mediator. Thus, we can only say that

our data largely cohere with this mediation story;

we do not (and cannot) establish mediation per se

within a single study. In the same way that race

may be masking a socio-economic effect that we

do not have good enough measures to detect,

variables we did not measure may be the

fundamental mediators between this intervention

and our outcomes. Future research that provides

data on other potential mediators (e.g., those not

assessed in this study) will also prove

tremendously helpful.

Other key future directions emerge out of the

results themselves. First, the Teacher Treatment

seemed to yield a greater effect on our outcomes

than the Student Treatment. When teachers

learned what they had in common with their

students, they felt they had more in common with

those students, perceived better relationships with

them, and those students seem to have better

grades. Although more speculative, it appears

that the Teacher Treatment may primarily affect the

underserved students. Thus, one set of future

studies might investigate whether the effects of the

intervention are really concentrated on teachers

and underserved students, or whether this finding

varies by context or population. Other studies

could investigate whether the intervention might be

adapted to improve students’ perceptions of the

relationship or to make it effective for all students

rather than just a subset of students. Additional

research might investigate the role of teachers’

race and/or the congruence between students’

and teachers’ race on the effectiveness of the

intervention.

Second, although consequential for students’

futures, grades have limitations as a key outcome

variable. Specifically, they leave substantial

ambiguity as to why the effects of the intervention

occur – a question that will be especially important

for future studies to address. One potential

explanation is rooted in interactions. Many

teachers may see it as a part of their role to

connect with students and form a positive working

relationship. Knowing what they have in common

with their students provides them with a lever

through which they can begin developing this

relationship. For a group of predominantly white

teachers, learning what they have in common with

their underserved students may be critically

important. Indeed, we find that teachers report

interacting with these students more frequently.

From this knowledge and the increased

interactions, teachers may connect better with

students at an interpersonal level and may be

better equipped to connect their subject matter to

students’ interests. If this scenario transpires,

greater learning seems a likely consequence. By

contrast, ninth graders (regardless of race) may

14

have little interest in connecting with their teachers

or having any more interactions than necessary.

They might be much more focused on connecting

with their peers during this developmental stage.

As a result, the students in this treatment group

may find few effects of the intervention beyond

greater perceived similarity with their teacher.

An alternative explanation is rooted in perceptual

biases. Perhaps teachers typically perceive their

students – particularly their underserved students

– in stereotypical fashion. However, when they

realize several domains in which they share some

common ground with these students, the teachers

perceive their relationships with these students in a

new way – more like members of their own in-

group (Hewstone, Rubin, & Willis, 2002). A

potential consequence is that teachers might

assign these students higher grades as a

consequence of perceiving them differently.

Our exploratory analyses suggest that the

possibility of perceptual biases will also be an

important, challenging area of future investigation.

On the one hand, we might expect students, who

are welcomed into a classroom where the teacher

more frequently interacts with them in positive

ways, to attend class more regularly and arrive on

time more often. While we did not find much

evidence congruent with this conjecture, there are

many factors that affect a student’s presence in

class.

On the other hand, the perceptual bias story may

not be completely congruent with the finding that

teachers report interacting more frequently with

students in the Teacher Treatment Condition than

with their control group peers. In other words, if

teachers interact with these students more

frequently, then the higher grades may partly be a

function of learning. Thus, research that can begin

to shed light on the mechanisms – be they

teacher-student interactions, teacher perceptions,

a combination of both, or other factors – through

which this intervention affects these important

outcomes of TSRs and grades will be especially

fruitful.

In closing, this study shows that (perceptions of)

real similarities can be influenced by a brief

intervention that affects real relationships in a

consequential setting like a high school. Our

findings suggest that the improvements in TSRs

may, in turn, cause downstream benefits for

students’ grades. Finally, these results generate

strong hypotheses that similar interventions in the

future may be effective in helping to close

achievement gaps between subgroups of

students.

Authors

Hunter Gehlbach: Harvard Graduate School of Education, 13 Appian Way, Cambridge, MA 02138

Maureen E. Brinkworth: Harvard Graduate School of Education, 13 Appian Way, Cambridge, MA 02138

Aaron M. King: Residential Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305

Laura M. Hsu: Merrimack College, School of Education and Social Policy, 315 Turnpike St., North Andover, MA 01845

Joe McIntyre: Harvard Graduate School of Education, 13 Appian Way, Cambridge, MA 02138

Todd Rogers: Harvard Kennedy School of Government, 79 John F. Kennedy St., Cambridge, MA 02138

Corresponding author:

Hunter Gehlbach: Longfellow 316, 13 Appian Way, Cambridge, MA 02138

(617) 496-7318 [email protected]

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from the Spencer Foundation and the National Science Foundation—Grant

#0966838. The conclusions reached are those of the investigators and do not necessarily represent the perspectives of the

funder. The authors are grateful to Geoff Cumming for his statistical guidance in response to a concern from reviewers.

We dedicate this article to the memory of Maureen Brinkworth (1983 – 2014). She passed away far too young and with far too

much of her abundant promise unrealized. She was equal parts intellectual inspiration for this work and logistical wizard who

made this study happen. Although she died while the article was under review, we hope she is smiling somewhere to see her

work acknowledged.

References:

Ames, D. (2004). Inside the mind-reader's toolkit: Projection

and stereotyping in mental state inference. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 340-353.

Asparouhov, T. (2005). Sampling weights in latent variable

modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary

Journal, 12(3), 411-434. doi: 10.1207/

s15328007sem1203_4

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How

much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates?

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249-275. doi:

10.1162/003355304772839588

Boer, D., Fischer, R., Strack, M., Bond, M. H., Lo, E., &

Lam, J. (2011). How shared preferences in music create

bonds between people: Values as the missing link.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(9),

1159-1171. doi: 10.1177/0146167211407521

Brady, S., Reeves, S. L., Garcia, J., Purdie-Vaughns, V.,

Cook, J. E., Taborsky-Barba, S., . . . Cohen, G. L. (this

issue). The psychology of the affirmed actor: Spontaneous

self-affirmation in the face of stress. Journal of Educational

Psychology.

Brinkworth, M. E., McIntyre, J., Harris, A. D., & Gehlbach,

H. (manuscript under review). Understanding teacher-

student relationships and student outcomes: The positives

and negatives of assessing both perspectives.

Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development

of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research,

27(1), 78-109.

Bullock, J. G., Green, D. P., & Ha, S. E. (2010). Yes, but

what's the mechanism? (Don't expect an easy answer).

Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 98(4), 550-558.

Burger, J. M., Messian, N., Patel, S., del Prado, A., &

Anderson, C. (2004). What a coincidence! The effects of

incidental similarity on compliance. Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, 30(1), 35-43. doi:

10.1177/0146167203258838

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008).

Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered

errors. Review of Economics & Statistics, 90(3), 414-427.

Chen, H., Luo, S., Yue, G., Xu, D., & Zhaoyang, R. (2009).

Do birds of a feather flock together in China? Personal

Relationships, 16(2), 167-186. doi: 10.1111/j.

1475-6811.2009.01217.x

Cialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and practice (5th

ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Cohen, G. L., Garcia, J., Apfel, N., & Master, A. (2006).

Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-

psychological intervention. Science, 313(5791), 1307-1310.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-

student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review

of Educational Research, 77(1), 113-143. doi:

10.3102/003465430298563

Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how.

Psychological Science, 25(1), 7-29. doi:

10.1177/0956797613504966

Dee, T. S. (2004). The race connection: Are teachers more

effective with students who share their ethnicity? Education

Next, 4(2), 52-59.

Donald, S. G., & Lang, K. (2007). Inference with difference-

in-differences and other panel data. Review of Economics &

Statistics, 89(2), 221-233.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M.,

Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. J. (1993).

Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-

environment fit on young adolescents' experiences in

schools and in families. Special Issue: Adolescence.

American Psychologist, 48(2), 90-101. doi:

10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-

taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype

accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 78(4), 708-724. doi:

10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.708

Garner, R. (2005). What's in a name? Persuasion perhaps.

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(2), 108-116.

Gehlbach, H., Brinkworth, M. E., & Harris, A. D. (2012).

Changes in teacher-student relationships. British Journal of

Educational Psychology, 82, 690-704. doi: 10.1111/j.

2044-8279.2011.02058.x

Gilbert, D. T. (2006). Stumbling on happiness (1st ed.). New

York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Gonzaga, G. C., Campos, B., & Bradbury, T. (2007).

Similarity, convergence, and relationship satisfaction in

dating and married couples. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 93(1), 34-48. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.34

Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early

adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and

achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(1),

21-43. doi: 10.1177/0272431693013001002

Hewstone, M., Rubin, M., & Willis, H. (2002). Intergroup

bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 575-604.

Hulleman, C. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2009). Promoting

interest and performance in high school science classes.

Science, 326(5958), 1410-1412. doi: 10.1126/science.

1177067

Ireland, M. E., Slatcher, R. B., Eastwick, P. W., Scissors, L.

E., Finkel, E. J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). Language style

matching predicts relationship initiation and stability.

Psychological Science, 22(1), 39-44. doi:

10.1177/0956797610392928

Jones, J. T., Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Mirenberg, M.

C. (2004). How do I love thee? Let me count the Js: Implicit

egotism and interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 87(5), 665-683. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.87.5.665

17

Leary, M. R. (2010). Affiliation, acceptance, and belonging:

The pursuit of interpersonal connection. In S. T. Fiske, D. T.

Gilbert & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology,

Vol 2 (5th ed.). (pp. 864-897). Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley

& Sons Inc.

Lieberman, M. D. (2013). Social: Why our brains are wired

to connect (First ed.). New York: Crown Publishers.

Mackinnon, S. P., Jordan, C. H., & Wilson, A. E. (2011).

Birds of a feather sit together: Physical similarity predicts

seating choice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,

37(7), 879-892. doi: 10.1177/0146167211402094

McCombs, B. L. (2014). Using a 360 degree assessment

model to support learning to learn. In R. Deakin-Crick, T.

Small & C. Stringher (Eds.), Learning to learn for all: theory,

practice and international research: A multidisciplinary and

lifelong perspective (pp. 241-270). London: Routledge.

McLaughlin, C., & Clarke, B. (2010). Relational matters: A

review of the impact of school experience on mental health

in early adolescence. Educational and Child Psychology,

27(1), 91-103.

Midgley, C., Feldlaufer, H., & Eccles, J. S. (1989). Student/

teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before

and after the transition to junior high school. Child

Development, 60(4), 981. doi:

10.1111/1467-8624.ep9676559

Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is

actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of

actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social and

Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889-922. doi:

10.1177/0265407508096700

Murdock, T. B. (1999). The social context of risk: Status and

motivational predictors of alienation in middle school.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 62-75. doi:

10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.62

Murdock, T. B., & Miller, A. (2003). Teachers as sources of

middle school students' motivational identity: Variable-

centered and person-centered analytic approaches. The

Elementary School Journal, 103(4), 383-399. doi:

10.1086/499732

Myers, D. G. (2015). Exploring social psychology (7th ed.).

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on

the role of student motivation in learning and teaching

contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4),

667-686.

Roeser, R. W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. C. (1996).

Perceptions of the school psychological environment and

early adolescents' psychological and behavioral functioning

in school: The mediating role of goals and belonging.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 408-422.

Roorda, D., Koomen, H., Split, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011).

The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on

students' school engagement and achievement: A meta-

analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4),

493-529. doi: 10.3102/0034654311421793

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory

and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social

development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1),

68-78.

Ryan, R. M., Stiller, J. D., & Lynch, J. H. (1994).

Representations of relationships to teachers, parents, and

friends as predictors of academic motivation and self-

esteem. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 14(2), 226-249.

Sakiz, G., Pape, S. J., & Hoy, A. W. (2012). Does perceived

teacher affective support matter for middle school students

in mathematics classrooms? Journal of School Psychology,

50(2), 235-255. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.

2011.10.005

Sherman, D. K., Hartson, K. A., Binning, K. R., Purdie-

Vaughns, V., Garcia, J., Taborsky-Barba, S., . . . Cohen, G.

L. (2013). Deflecting the trajectory and changing the

narrative: How self-affirmation affects academic

performance and motivation under identity threat. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 591-618. doi:

10.1037/a0031495

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011).

False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data

collection and analysis allows presenting anything as

significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359-1366. doi:

10.1177/0956797611417632

Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Kim, H. S., Jarcho, J., Takagi,

K., & Dunagan, M. S. (2004). Culture and social support:

Who seeks it and why? Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 87(3), 354-362. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.354

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-

belonging intervention improves academic and health

outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023),

1447-1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364

Wentzel, K. R. (1997). Student motivation in middle school:

The role of perceived pedagogical caring. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 89(3), 411-419. doi:

10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.411

Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in

middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 202-209.

Wentzel, K. R. (2002). Are effective teachers like good

parents? Teaching styles and student adjustment in early

adolescence. Child Development, 73(1), 287-301. doi:

10.1111/1467-8624.00406

References:

18

Statement of Transparency

Increasingly, scholars have voiced skepticism about the

validity of nuanced findings in psychology that may have

resulted from practices such as post-hoc data mining

(Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011). Several

approaches seem promising, although it is clear that more

experience and research will need to occur before

consensus can be reached on the optimal set of

approaches. One particularly promising approach entails

the development of registries where scientists would provide

a brief description of their intended study before beginning

the research, list the variables that they will collect, and,

perhaps most importantly, list their hypotheses a priori –

what Cumming (2014) would describe as “pre-specified”

hypotheses.

Unfortunately, this approach is not possible for the present

study. We collected the data for this research before

becoming aware of the practice of registering studies (and

still remain unaware of websites that facilitate the

registration of psychological studies). We also have

concerns about how this practice should play out ideally –

particularly with regard to field experiments like the present

investigation. Registering a study ahead of time should

work well if random assignment works, if implementation of

the intervention is high in its fidelity, and unforeseen

circumstances do not arise. However, in the messiness of

the real world, studies are rarely implemented perfectly and

predicting all possible contingencies and compensatory

steps that may be required seems unrealistic. Finally, it

seems reasonable that scholars might want to weight their

confidence in different hypotheses along a sliding scale. For

example, a pre-specified hypothesis that a manipulation

check will work seems much safer (and less interesting)

than predicting that a particular treatment will be

simultaneously moderated by race and mediated by a

personality trait.

There is clear value to these new steps for the integrity of

psychological science, yet there are challenges in figuring

out how to adjust to these new recommendations. In the

hopes of finding a middle ground, we are writing this

statement of transparency on March 13, 2014 – the day

before we begin any data analysis. We hope this step

maximizes the integrity of our study. This statement will not

be edited in any way once data analysis commences. We

hope that this approach might have some strengths that

other scholars may benefit from; undoubtedly, this approach

will have weaknesses that we hope others help us to learn

from. In this statement, we describe the following features

of the study:

A background section which overviews the

preliminary pilots that informed the current study.

A list of the variables collected which denotes the

variables we intend to use in the analysis for the

current study (in contrast to those we are

interested in for other studies).

A list of hypotheses which denotes a set of clear

“pre-specified” hypotheses. All other analyses

conducted in our final manuscript should be

viewed as exploratory, hypothesis-generating

findings.

Key details of the analytic choices that we are

making ahead of time.

Background to the present study

This data collection represents the third time we have

implemented an intervention similar to the present one at

the school in question. The basic procedure was always

the same as what is described in the methods section: We

give teachers and students a “get-to-know-you” survey,

randomly assign them to get feedback (or not) about what

they have in common with the other party, ask them to

reflect on that feedback, follow up with a longer survey

shortly before the end of the marking period, and collect

grades and student record data after the quarter ends. We

first ran this field experiment during the 2011-12 school year

with a convenience sample of 10

th

grade classes. Overly

confident from laboratory studies suggesting that even trivial

commonalities could change individuals’ affect and behavior

for each other (Ames, 2004; Burger, Messian, Patel, del

Prado, & Anderson, 2004), we were relatively cavalier about

what types of similarities we asked teachers and students

about (e.g., favorite pizza toppings, preference for crunchy

versus smooth peanut butter, etc.). We found no clear

effects from this study. That spring we conducted an open-

ended survey with 9

th

graders to learn what types of

commonalities they might value having with their teachers.

These data allowed us to substantially revise the “get-to-

know-you” survey.

For the 2012-13 school year we conducted the study again

with several important changes. First, we used the revised

get to know you survey. Second, our Year 1 analyses

yielded a suggestive finding that perhaps the student

control group (who received feedback on what they had in

common with other students in their grade) might have

actually benefitted from a heightened sense of belonging at

their school. So for Year 2, we changed the control group’s

feedback to learning what they had in common with

Statement of Transparency

19

students from a school in a different state. Third, we added

an additional treatment group that would learn what they

had in common with students from their own grade (i.e., to

see whether the control condition from the previous year

really was having a positive effect). Fourth, we ran the

intervention with 9

th

graders, thinking that they might benefit

the most given the often challenging transition to high

school.

These data showed promising, though mildly vexing results.

Specifically, the similarity manipulation seemed to work:

both teachers and students in the treatment conditions

perceived greater similarity to the other party. The

intervention produced a clear boost in the positivity of the

teacher-student relationship from the teacher’s perspective.

However, the effect of the intervention on the students’

perceptions of their relationship with their teacher was much

less clear. The intervention manifested a significant, positive

effect on students’ mid-quarter grades. This trend dropped

to non-significance by the end of the quarter, but the effects

were still in the same direction. We found no suggestions

that the sense of belonging intervention had any effect.

Based on these encouraging, but mixed findings from our

similarity intervention and our modest sample size (N = 101,

spread across four conditions), we decided to try to

replicate the intervention in the current 2013-14 school year.

We dropped the sense of belonging intervention conditions

to maximize our power for the similarity intervention.

However, no substantive changes were made to the

similarity intervention itself from 2012-13 to 2013-14.

List of variables in the present study

Note: Bolded variables indicate which variables that will be

included in the analyses for this study.

Statement of Transparency

20

Hypotheses

We will test the following prescriptive hypotheses:

Similarity:

o

Students who receive feedback that they

have commonalities with their teacher will

report a greater sense of similarity to their

teacher on the student-reported 6-item

similarity scale.

o

Teachers who receive feedback that they

have commonalities with a particular

student will report a greater sense of

similarity to that student on the teacher-

reported similarity item.

Teacher-student relationship:

o

Students who receive feedback that they

have commonalities with their teacher will

report perceiving a more positive teacher-

student relationship (i.e., the 9-item

student-report measure).

o

Teachers who receive feedback that they

have commonalities with their student will

report perceiving a more positive teacher-

student relationship (i.e., the 9-item

teacher-report measure).

Grades:

o

Students of teachers who receive

feedback that they have commonalities

with their student will earn higher mid-

term grades in their focal class.

o

Students of teachers who receive

feedback that they have commonalities

with their student will earn higher final

marking period grades in their focal class.

We have arrayed these prescriptive hypotheses such that

we are most confident about the hypotheses listed towards