1

Walking Catfish (Clarias batrachus)

Ecological Risk Screening Summary

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, April 2011

Revised, January 2017, July 2017

Web Version, 6/14/2018

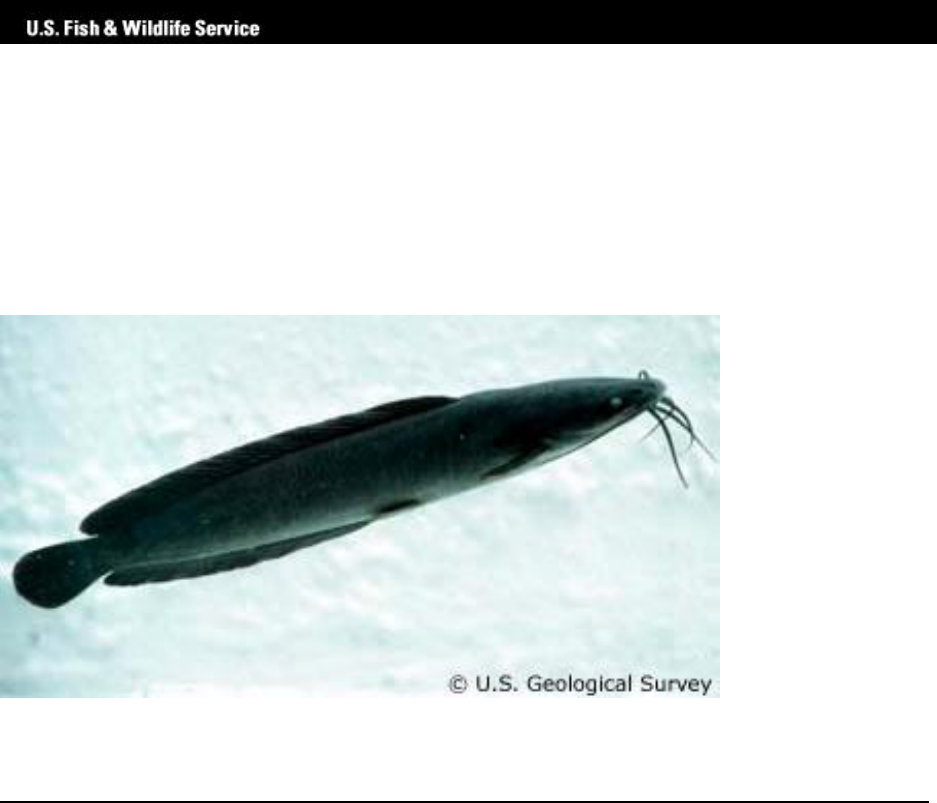

Photo: USGS. Licensed under Public Domain – Government Work.

1 Native Range and Status in the United States

Native Range

From Nico et al. (2017):

“Southeastern Asia including eastern India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Burma, Indonesia,

Singapore, and Borneo (Lee et al. 1980 et seq.; Talwar and Jhingran 1992; Kottelat et al. 1993).

Laos (Baird et al. 1999).”

Status in the United States

From Nico et al. (2017):

“This species has been collected in California from the All American Canal west of Yuma,

Arizona (Minckley 1973; Courtenay et al. 1984); from the San Joaquin River, Sacramento

County (Courtenay and Hensley 1979a; Courtenay et al. 1984, 1986); and from Legg Lake, Los

Angeles County (Shapovalov et al. 1981). Specimens have been captured in widely separated

water bodies in Connecticut (Whitworth 1996). It has been firmly established in southern

2

peninsular Florida since the late 1960s, including Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge,

Charlotte Harbor, Myakka River, Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge, Big Cypress National

Preserve and Everglades National Park (Courtenay 1970, 1978, 1979a; Courtenay et al. 1974;

Courtenay and Miley 1975; Courtenay and Hensley 1979a; Loftus and Kushlan 1987;

Anonymous 1983a; Lorenz et al. 1997; Tilmant 1999; Charlotte Harbor NEP 2004; USFWS

2005; Lemon, personal communication; Galvez, personal communication). They have also

become established in Kissimmee and Lake Okeechobee drainages (Nico 2005[b]), and

individuals have been collected in the Tampa Bay region (e.g., Little Manatee River;

Hillsbororugh, Pinellas, and Pasco counties) and from the Indian River system near Daytona

Beach. A specimen has been taken from the Flint River in Georgia (Courtenay and Miley 1975;

Courtenay and Hensley 1979a; Courtenay et al. 1984, 1991; Gennings, personal

communication). A single fish was taken by an angler from Waldo Lake, Brockton in Plymouth

County, Massachusetts, in August 1971; three or four additional fish were reportedly taken from

ponds in the eastern part of the state in the mid-1970s, but the specimens were not retained

(Hartel 1992; Cardoza et al. 1993; Hartel et al. 1996). Two specimens were taken from Rogers

Spring, Clark County, Nevada (Courtenay and Deacon 1983; Deacon and Williams 1984).

Populations have failed throughout Nevada (Vinyard 2001).”

“Established in Florida; failed in California, Connecticut, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Nevada.”

“In 1968, this species was confined to three south Florida counties; by 1978, it had spread to 20

counties in the southern half of the peninsula (Courtenay 1979a; Courtenay et al. 1986).

Dispersal apparently has occurred by way of the interconnected network of canals along the

southeastern coastal region; however, spread was accelerated by overland migration, typically

during rainy nights (Loftus and Kushlan 1987). Its ability to use atmospheric oxygen assists in

survival in low-oxygen habitats (Loftus 1979). The walking catfish has been established in

Everglades National Park and in Big Cypress National Preserve since the mid-1970s (Courtenay

1989). Populations suffer periodic die-offs from cold temperatures and subsequent bacterial

infection (Loftus and Kushlan 1987); consequently, northward dispersal is limited (Courtenay

1978, Courtenay and Stauffer 1990). Although all Florida imports were originally albinos,

albinos in the wild are now rare and descendants have reverted to the dominant, dark-color phase

(dark brown to gray) probably a result of natural selection by predators (Courtenay et al. 1974;

Courtenay and Stauffer 1990). Guarding of free-swimming young may enhance survivorship

over that of native species with less advanced (or no) parental care (Taylor et al. 1984).”

From Masterson (2007):

“C. batrachus, a southeastern Asian native species, is now established throughout most of

Florida (Courtenay et al. 1991), although Shafland and Pestrak (1982) suggest that cold

intolerance puts the northernmost limit of potential range expansion at approximately

Gainsville.”

3

Means of Introductions in the United States

From Nico et al. (2017):

“The walking catfish was imported to Florida, reportedly from Thailand, in the early 1960s for

the aquarium trade (Courtenay et al. 1986). The first introductions apparently occurred in the

mid-1960s when adult fish imported as brood stock escaped, either from a fish farm in

northeastern Broward County or from a truck transporting brood fish between Dade and Broward

counties (Courtenay and Miley 1975; Courtenay 1979a; Courtenay and Hensley 1979a;

Courtenay et al. 1986). Additional introductions in Florida, supposedly purposeful releases, were

made by fish farmers in the Tampa Bay area, Hillsborough County in late 1967 or early 1968,

after the state banned the importation and possession of walking catfish (Courtenay and Stauffer

1990). Aquarium releases likely are responsible for introductions in other states (Courtenay and

Hensley 1979a; Courtenay and Stauffer 1990; Hartel 1992). Dill and Cordone (1997) reported

that this species has been sold by tropical fish dealers in California for some time.”

Remarks

From GISD (2011):

“Clarias batrachus can survive out of water for quite sometime using its auxiliary breathing

organs and move short distances over land allowing it to migrate to new water bodies (Froese

and Pauly, 2009).”

“This species has been nominated as among 100 of the "World's Worst" invaders”

From Masterson (2007):

“In Florida, novices may confuse this species [Clarias batrachus] with the native Ariid marine

hardhead catfish (Ariopsis felis) and gafftopsail catfish (Bagre marinus). However, the forked

tail, adipose fin set anterior to the caudal peduncle, and the presence of a dorsal spine on the

native species are among the many features that easily differentiate them from C. batrachus.

Similar distinguishing features can be used to distinguish C. batrachus from resident freshwater

Ictalurid catfish such as the brown bullhead (Ictalurus nebulosus) and channel catfish (I.

punctatus).”

2 Biology and Ecology

Taxonomic Hierarchy and Taxonomic Standing

From ITIS (2014):

“Kingdom Animalia

Subkingdom Bilateria

Infrakingdom Deuterostomia

Phylum Chordata

Subphylum Vertebrata

4

Infraphylum Gnathostomata

Superclass Osteichthyes

Class Actinopterygii

Subclass Neopterygii

Infraclass Teleostei

Superorder Ostariophysi

Order Siluriformes

Family Clariidae

Genus Clarias Scopoli, 1777

Species Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus, 1758)”

According to Eschmeyer et al. (2017), Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus 1758) is the valid name for

this species. Clarias batrachus was originally described as Silurus batrachus Linnaeus 1758.

Size, Weight, and Age Range

From Nico et al. (2017):

“Size: 61 cm in native range; rarely”

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Maturity: Lm 28.0 range ? - ? cm

Max length: 47.0 cm TL male/unsexed; [IGFA 2001]; common length: 26.3 cm TL

male/unsexed; [Hugg 1996]; max. published weight: 1.2 kg [IGFA 2001]”

From Masterson (2007):

“Walking catfish typically attain a standard length of 225-300 mm, although animals twice that

size are encountered (Courtenay and Miley 1975; Hensley and Courtenay 1980).”

Environment

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“[…] freshwater; brackish; depth range 1 - ? m [Herre 1924]. […]; 10°C - 28°C [assumed to be

recommended aquarium temperature range] [Baensch and Riehl 1985]; […]”

From GISD (2011):

“[…] it is also reported to occur in intercoastal waterways of salinities up to 18 ppt.”

Climate/Range

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Tropical; […]; 29°N - 7°S”

5

From GISD (2011):

“[…] moderate tolerance to colder waters with a reported a [sic] lower lethal temperature of

9.8°C.”

Distribution Outside the United States

Native

From Nico et al. (2017):

“Southeastern Asia including eastern India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Burma, Indonesia,

Singapore, and Borneo (Lee et al. 1980 et seq.; Talwar and Jhingran 1992; Kottelat et al. 1993).

Laos (Baird et al. 1999).”

Introduced

From GISD (2011):

“Known introduced range: Indonesia (Sulawesi), USA, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, UK, Papua

New Guinea, Guam, Taiwan, Thailand (FishBase, 2003). Probably introduced into the

Philippines (Nico, 2005[b]).”

From NIES (2017):

“Range in Japan: Okinawajima Island.”

Means of Introduction Outside the United States

From GISD (2011):

“Introduction pathways to new locations

Aquaculture: Introduced into Hong Kong from Thailand for aquaculture, (FishBase, 2003).

Pet/aquarium trade: The walking catfish was imported to Florida, reportedly from Thailand, in

the early 1960s for the aquarium trade (Courtenay et al. 1986).

Local dispersal methods

Aquaculture (local): Aquarium releases likely are responsible for introductions in other states of

America. (Nico, 2005[b])

Escape from confinement: In Florida adult fish imported as brood stock escaped from

confinement, either from a fish farm in northeastern Broward County or from a truck

transporting brood fish between Dade and Broward counties. (Nico, 2005[b])

Other (local): Dill and Cordone (1997) reported that this species has been sold by tropical fish

dealers in California for some time. (Nico, 2005[b])

Water currents: In America dispersal apparently has occurred by way of the interconnected

network of canals along the southeastern coastal region. (Nico, 2005[b])”

From NIES (2017):

“Route: Deliberate: distributed as pet animal.”

6

Short Description

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Dorsal spines (total): 0; Dorsal soft rays (total): 60-76; Anal spines: 0; Anal soft rays: 47 - 58.

Body compressed posteriorly. Upper jaw a little projecting. Spine of pectoral fins rough on its

outer edge and serrated on its inner edge [Taki 1974]. Occipital process more or less triangular,

its length about 2 time in its width [Kottelat 1998]; distance between dorsal and occipital process

4-5.5 times in distance from tip of snout to end of occipital process [Kottelat 2001]. Genital

papilla in males is elongated and pointed [Ros 2004].”

From GISD (2011):

“Clarias batrachus has a broad, flat head and an elongate body which tapers toward the tail. It is

readily recognizable as a catfish with four pairs of barbels whiskers and fleshy, papillated lips.

The teeth are villiform, occurring in patches on the jaw and palate. Its eyes are small. The dorsal

fin is continuous and extends along the back two-thirds of the length of the body but there is no

dorsal spine. The dorsal, caudal, and anal fins together form a near-continuous margin; the

caudal fin is rounded and not eel-like though it is occasionally fused with the other fins. Its

pectoral spines are large and robust and finely serrate along the margins with which it walks

accompanied by a back and forth flexion. Their coloration is olive to dark brown or purple to

black above, blue green on the sides and white below, with white specks on their rear side. C.

batrachus may be easily distinguished from many of the North American Ictalurid catfishes in

that the walking catfish lacks an adipose fin (Masterson, 2007; Robins, undated; GSMFC,

2006).”

From CABI (2017):

“C. batrachus has an elongated body, broad at the anterior and narrow at the posterior. C.

batrachus is similar in size and appearance to C. macrocephalus but can be distinguished from

the latter species by the shape of the occipital process in the head portion. The occipital process

is round-shaped in C. macrocephalus but pointed in C. batrachus. Unlike C. macrocephalus, C.

batrachus does not have large numbers of small white spots along the sides of its body (Teugels

et al., 1999). C. batrachus lacks an adipose fin. Dorsal and anal fins are without spines, pectoral

fins are strong with fine serrations on both edges, pelvic fins are small and the caudal fin is not

confluent with dorsal or anal fin. The mouth is wide and has four pairs of well-developed

barbels, with the maxillary barbels reaching to the middle or base of the pectoral fin (Talwar and

Jhingran, 1991).”

“The body of the normal coloured variety is greyish to olive in colour with a whitish underside.

Other varieties include albino with a white body and reddish eyes, and a pink variety with

normal coloured eyes (Axelrod et al., 1971). Various multi-coloured varieties are becoming more

common in the tropical fish aquarium trade.”

7

Biology

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Can live out of water for quite sometime and move short distances over land [Talwar and

Jhingran 1991]. Can walk and leave the water to migrate to other water bodies using its auxiliary

breathing organs. […] Feed on insect larvae, earthworms, shells, shrimps, small fish, aquatic

plants and debris [Ukkatawewat 2005]. […] Recently rare, being replaced by introduced African

walking catfish [Vidthayanon 2002].”

“Inhabits lowland streams [Vidthayanon 2002], swamps, ponds, ditches, rice paddies, and pools

left in low spots after rivers have been in flood [Herre 1924, Vidthayanon 2002]. Usually

confined to stagnant, muddy water [Rahman 1989]. Found in medium to large-sized rivers,

flooded fields and stagnant water bodies including sluggish flowing canals [Taki 1978].

Undertakes lateral migrations from the Mekong mainstream, or other permanent water bodies, to

flooded areas during the flood season and returns to the permanent water bodies at the onset of

the dry season [Sokheng et al. 1999].”

From GISD (2011):

“Nutrition

Clarias batrachus feeds on insect larvae, earthworms, shells, shrimps, small fish, aquatic plants

and debris.

Reproduction

Clarias batrachus engages in mass spawning migrations in late spring and early summer.

Inundated rice paddy fields have been reported as favored spawning grounds over its native

range. The pair manifests the 'spawning embrace' which is widely observed in other catfish

species. Mating occurs repeatedly for as long as 20 hours. The pair gently nudge each other in

the genital region and flick their dorsal fins; male wraps his body around the female, then the

female releases a stream of hundreds to thousands of adhesive eggs into the nest or on

submerged vegetation. Males guard the nests and embryos hatch in about 30 hours. Both parents

guard fry for about three days, when they develop barbles visible to the naked eye and swim

freely (GSMFC, 2006; FishBase, 2009, Ros, 2004c).”

“Lifecycle stages

In southeast Asia, spawning period is during the rainy season, when rivers rise and fish are able

to excavate nests in submerged mud banks and dikes of flooded rice fields (FishBase, 2003).”

From Masterson (2007):

“Individuals become sexually mature at approximately one year of age (Talwar and Jhingran

1991). Where populations are established, walking catfish exhibit rainy season mass migration

and spawning events. Adhesive egg masses containing as many as 1,000 eggs are laid in nesting

hollows prepared by the breeding pair. Egg masses are found on on [sic] aquatic vegetation or

within other suitable nest sites. They are guarded by the males until they hatch (Courtenay et al.

1974, Hensley and Courtenay 1980). The female, leaving care of the eggs to the male, guards the

area around the nest.”

8

“Embryonic development within the egg is rapid. Embryos hatch out in approximately 30 hours

at 25°C. For the first two days after hatching, parents still remain by the nest to protect the fry.

At this stage, the fry are egg-sac larvae that do not yet feed, but instead live off of energy

reserves stored in the yolk sac for the first two to three days after hatching (Rao et al. 1995).

When the free-swimming young have consumed the remaining yolk reserves, they begin to

forage for themselves.”

Human Uses

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Fisheries: commercial; aquaculture: commercial; aquarium: commercial”

“The Lao use this fish as lap pa or ponne pa [traditional fish dishes]. […] An important food fish

[Talwar and Jhingran 1991] that is marketed live, fresh and frozen [Frimodt 1995].”

From GISD (2011):

“They have become a significant source of food and for inhabitants and income for local

fisheries (Joshi, undated).”

Diseases

No records of OIE reportable diseases.

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Dactylogyrus Gill Flukes Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Skin Flukes, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Gonad Nematodosis Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Sporozoa Infection (Hennegya sp.), Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Sporozoa-infection (Myxobolus sp.), Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Haplorchis Infestation 1, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Posthodiplostomum Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Clinostomoides Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Neodiplostomum Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Orientocreadium Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Gauhatian Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Opegaster Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Phyllodistomum Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Boviena Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Lytocestus Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Gnathostoma Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Procamallanus Infection 1, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Cristaria Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Bacterial Infections (general), Bacterial diseases

Anchor worm Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

9

Dactylogyrus Gill Flukes Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Trichodinosis, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Yellow Grub, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Camallanus Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Acanthogyrus Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Clinostomum Infestation (metacercaria), Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Acanthogyrus Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Sporozoa-infection (Myxobolus sp.), Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Orientocreadium Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Boviena Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Lytocestus Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Gnathostoma Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Procamallanus Infection 1, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Procamallanus Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Procamallanus Infection 5, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Procamallanus Disease 2, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Pallisentis Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Hemiclepsis Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Palaeorchis Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Procamallanus Infection 6, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Masenia Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Phyllodistomum Infestation 3, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Posthodiplostomum Infestation 2, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Dactylogyrus Infestation 1, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Capingentoides Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Djombangia Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Gyrocotyle Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Lytocestus Disease (Lytocestus sp.), Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Lytocestus Infestation 1, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Lytocestus Infestation 2, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Lytocestus Infestation 3, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Monobothrioides Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Pseudocaryophyllaeus Infestation 2, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Pseudolytocestus Infestation, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Ascaridia Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Echinocephalus Disease, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Pallisentis Infestation 3, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)

Columnaris Disease (e.), Bacterial diseases

Fungal Infection (general), Fungal diseases

Aeromonosis, Bacterial diseases

Enteric Septicaemia of Catfish, Parasitic infestations (protozoa, worms, etc.)”

Threat to Humans

From Froese and Pauly (2011):

“Potential pest”

10

3 Impacts of Introductions

From Nico et al. (2017):

“Largely unknown. In Florida, walking catfish are known to have invaded aquaculture farms,

entering ponds where these predators prey on fish stocks. In response, fish farmers have had to

erect protective fences to protect ponds (Courtenay and Stauffer 1990). Loftus (1988) reported

heavy predation on native fishes in remnant pools during seasonal drying of wetlands. Baber and

Babbitt (2003) examined predation impacts on tadpole assemblages in temporary wetlands in

south-central Florida, and found that native fishes (e.g., eastern mosquitofish Gambusia

holbrooki, golden topminnow Fundulus chrysotus, flagfish Jordanella floridae) had larger

impacts and higher predation rates on tadpoles than C. batrachus.”

From GISD (2011):

“Clarias batrachus in South Florida are known to invade commercial aquaculture facilities, often

consuming vast numbers of the stocks of fishes (Robins, undated). The impacts from this

opportunist feeder are probably most pronounced in small, isolated wetland ponds where

walking catfish quickly consume or outcompete other resident populations to become the

dominant species in the pond. Resident centrarchids (freshwater sunfish) and native catfish

species appear particularly susceptible to impacts from this invader (Masterson, 2007). C.

batrachus can also negatively impact native amphibian populations by preying on tadpoles. The

ability of walking catfish to exploit isolated, ephemeral water bodies allows them to access

tadpole prey stocks that other fish cannot reach (Masterson, 2007).”

“The intensive dispersal of the species in Luzon [the Philippines] in the 1970s led to the

displacement of the native catfish in irrigation systems, lakes and rivers. It has completely

dominated natural populations in lakes and rivers and the indigenous Clarias macrocephalus can

hardly be found in the markets today.”

“Clarias batrachus threatens endemic fresh water fishes in Sri Lanka (Kotagama &

Bambaradeniya, 2006).”

“Clarias batrachus will outcompete or directly consume several co-occurring native species in

Florida. Resident centrarchids, freshwater sunfish, and native catfish species appear particularly

susceptible to impacts from this invader. C. batrachus can also negatively impact native

amphibian populations by preying on tadpoles (Masterson, 2007).”

“Clarias batrachus in South Florida are known to invade commercial aquaculture facilities, often

consuming vast numbers of the stocks of fishes (Robins, undated).”

From Masterson (2007):

“One specific example of an observed economic impacts is the cost associated with barrier

fences. Florida fish farmers have had to install such fences to keep walking catfish out of their

ponds (Courtenay and Stauffer 1990, Nico 2005[a]).”

11

From NIES (2017):

“Impact [in Japan]: Predation and competition against native species.”

4 Global Distribution

Figure 1. Known global distribution of Clarias batrachus as reported by GBIF Secretariat

(2011). Locations are in southern Asia and Florida.

Figure 2. Known distribution of Clarias batrachus in Japan. Map from NIES (2017).

12

5 Distribution Within the United States

Figure 3. Known United States distribution of Clarias batrachus as reported by the USGS NAS

Database (Nico et al. 2017).

The points in Arizona, California, Georgia, and Massachusetts are from failed introductions and

subsequently were not used as source locations in the climate match.

13

6 Climate Matching

Summary of Climate Matching Analysis

The climate match for Clarias batrachus was high in southern Florida, the Southeast, and along

the Gulf Coast, and was low across the rest of the United States. The Climate 6 score (Sanders et

al. 2014; 16 climate variables; Euclidean distance) for the contiguous United States was 0.041,

medium, and individually high in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

Figure 4. RAMP (Sanders et al. 2014) source map showing weather stations in the United States

and South Asia selected as source locations (red) and non-source locations (grey) for Clarias

batrachus climate matching. Source locations from GBIF Secretariat (2011) and USGS NAS

Database (Nico et al. 2017).

14

Figure 5. Map of RAMP (Sanders et al. 2014) climate matches for Clarias batrachus in the

contiguous United States based on source locations reported by GBIF Secretariat (2011) and

USGS NAS Database (Nico et al. 2017). 0 = Lowest match, 10 = Highest match.

The High, Medium, and Low Climate match Categories are based on the following table:

Climate 6: Proportion of

(Sum of Climate Scores 6-10) / (Sum of total

Climate Scores)

Climate

Match

Category

0.000≤X≤0.005

Low

0.005<X<0.103

Medium

≥0.103

High

7 Certainty of Assessment

The certainty of this assessment is medium. Clarias batrachus had adequate information

available about its biology, ecology, and invasiveness for the assessment. The negative impacts

of C. batrachus introductions have been demonstrated.

15

8 Risk Assessment

Summary of Risk to the Contiguous United States

The history of invasiveness is high. There are many documented introductions and adverse

impacts reported from Florida. The climate match is medium, with the highest match in Florida

and the extreme Southeast. The certainty of assessment is medium. The overall risk assessment

category is high.

Assessment Elements

History of Invasiveness (Sec. 3): High

Climate Match (Sec. 6): Medium

Certainty of Assessment (Sec. 7): Medium

Remarks/Important additional information No additional remarks.

Overall Risk Assessment Category: High

9 References

Note: The following references were accessed for this ERSS. References cited within

quoted text but not accessed are included below in Section 10.

CABI. 2017. Clarias batrachus [original text by W.-K. Ng]. In Invasive Species Compendium.

CAB International, Wallingford, UK. Available:

http://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/88681. (January 2017).

Eschmeyer, W. N., R. Fricke, and R. van der Laan, editors. 2017. Catalog of fishes: genera,

species, references. Available:

http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp.

(January 2017).

Froese, R., and D. Pauly, editors. 2011. Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus, 1758). FishBase.

Available: http://www.fishbase.org/Summary/SpeciesSummary.php?ID=3054. (April

2011).

GBIF Secretariat. 2011. GBIF backbone taxonomy: Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus, 1758). Global

Biodiversity Information Facility, Copenhagen. Available:

http://data.gbif.org/species/5202683. (April 2011).

GISD (Global Invasive Species Database). 2011. Species profile: Clarias batrachus. Invasive

Species Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland. Available:

http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=62&fr=1&sts=sss&lang=EN. (April

2011).

16

ITIS (Integrated Taxonomic Information System). 2014. Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus, 1758).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System, Reston, Virginia. Available:

http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=1641

20. (March 2014).

Masterson, J. 2007. Indian River Lagoon species inventory: Clarias batrachus. Smithsonian

Marine Station at Fort Pierce. Available:

http://www.sms.si.edu/irlspec/Clarias_batrachus.htm. (January 2017).

Nico, L., M. Neilson, and B. Loftus. 2017. Clarias batrachus. U.S. Geological Survey,

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, Florida. Available:

http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=486. (January 2017).

NIES (National Institute for Environmental Studies). 2017. Clarias batrachus. In Invasive

species of Japan. National Research and Development Agency, National Institute for

Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan. Available:

http://www.nies.go.jp/biodiversity/invasive/DB/detail/51080e.html. (January 2017).

Sanders, S., C. Castiglione, and M. Hoff. 2014. Risk assessment mapping program: RAMP. U.S.

Fish and Wildlife Service.

10 References Quoted But Not Accessed

Note: The following references are cited within quoted text within this ERSS, but were not

accessed for its preparation. They are included here to provide the reader with more

information.

Anonymous. 1983a. Spiny 'walking catfish' moving upstate, spotted in Vero Beach. Sun-

Sentinel, October 19.

Axelrod, H. R., C. W. Emmens, D. Sculthrope, W. V. Winkler, and N. Pronek. 1971. Exotic

tropical fishes. TFH Publications, Jersey City, New Jersey.

Baensch, H. A., and R. Riehl. 1985. Aquarien atlas. Band 2. Mergus, Verlag für Natur-und

Heimtierkunde GmbH, Melle, Germany.

Baird, I. G., V. Inthaphaisy, P. Kisouvannalath, B. Phylavanh, and B. Mounsouphom. 1999. The

fishes of southern Lao. Lao Community Fisheries and Dolphin Protection Project.

Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Lao PDR.

Baber, M. J., and K. J. Babbitt. 2003. The relative impacts of native and introduced predatory

fish on a temporary wetland tadpole assemblage. Oecologia 136:289–295.

Cardoza, J. E., G. S. Jones, T. W. French, and D. B. Halliwell. 1993. Exotic and translocated

vertebrates of Massachusetts, 2nd edition. Fauna of Massachusetts Series 6.

Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Publication 17223-110-200-11/93-C.R,

Westborough.

17

Charlotte Harbor National Estuary Program (NEP). 2004. Minutes of the technical advisory

committee, habitat conservation subcommittee. February 19, 2004, Punta Gorda, Florida.

Available: http://www.chnep.org/NEP/minutes-2004/HCS2-19-04minutes.pdf.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr. 1970. Florida's walking catfish. Ward's Natural Science Bulletin 10(69):1,

4, 6.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr. 1978. Additional range expansion in Florida of the introduced walking

catfish. Environmental Conservation 5(4):273–275.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr. 1979a. Continued range expansion of the walking catfish. Environmental

Conservation 6(1):20.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr. 1989. Exotic fishes in the National Park system. Pages 237–252 in L. K.

Thomas, editor. Proceedings of the 1986 conference on science in the national parks,

volume 5. Management of exotic species in natural communities. U.S. National Park

Service and George Wright Society, Washington, D.C.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., and J. E. Deacon. 1983. Fish introductions in the American southwest: a

case history of Rogers Spring, Nevada. Southwestern Naturalist 28:221–224.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., and D. A. Hensley. 1979a. Survey of introduced non-native fishes. Phase I

Report. Introduced exotic fishes in North America: status 1979. National Fishery

Research Laboratory, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Gainesville, Florida.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., D. A. Hensley, J. N. Taylor, and J. A. McCann. 1984. Distribution of

exotic fishes in the continental United States. Pages 41–77 in W. R. Courtenay, Jr., and J.

R. Stauffer, Jr., editors. Distribution, biology, and management of exotic fishes. John

Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., D. A. Hensley, J. N. Taylor, and J. A. McCann. 1986. Distribution of

exotic fishes in North America. Pages 675–698 in C. H. Hocutt, and E. O. Wiley, editors.

The zoogeography of North American freshwater fishes. John Wiley and Sons, New

York.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., D. P. Jennings, and J. D. Williams. 1991. Appendix 2: exotic fishes. Pages

97–107 in C. R. Robins, R. M. Bailey, C. E. Bond, J. R. Brooker, E. A. Lachner, R. N.

Lea, and W. B. Scott. Common and scientific names of fishes from the United States and

Canada, 5th edition. American Fisheries Society, Special Publication 20, Bethesda,

Maryland.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., and W. W. Miley, II. 1975. Range expansion and environmental impress

of the introduced walking catfish in the United States. Environmental Conservation

2(2):145–148.

18

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., H. F. Sahlman, W. W. Miley II, and D. J. Herrema. 1974. Exotic fishes in

fresh and brackish waters of Florida. Biological Conservation 6(4):292–302.

Courtenay, W. R., Jr., and J. R. Stauffer, Jr. 1990. The introduced fish problem and the aquarium

fish industry. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 21(3):145–159.

Deacon, J. E., and J. E. Williams. 1984. Annotated list of the fishes of Nevada. Proceedings of

the Biological Society of Washington 97(1):103–118.

Dill, W. A., and A. J. Cordone. 1997. History and status of introduced fishes in California, 1871-

1996. California Department of Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 178.

Fishbase. 2003. Species profile Clarias batrachus Walking catfish. Available:

http://www.fishbase.org/Summary/SpeciesSummary.cfm?ID=3054&genusname=Clarias

&speciesname=batrachus.

Fishbase. 2009. [Source material did not give full citation for this reference.]

Frimodt, C. 1995. Multilingual illustrated guide to the world's commercial warmwater fish.

Fishing News Books, Osney Mead, Oxford, England.

Froese, R., and D. Pauly, editors. 2009. Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus, 1758). FishBase.

Available: www.fishbase.org. (June 2009).

GSMFC. 2006. [Source material did not give full citation for this reference.]

Hartel, K. E. 1992. Non-native fishes known from Massachusetts freshwaters. Occasional

Reports of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge,

Massachusetts.

Hartel, et al. 1996. [Source material did not give full citation for this reference.]

Hensley, D. A., and W. R. Courtenay, Jr. 1980. Clarias batrachus (Linnaeus) Walking Catfish.

Page 475 in D. S. Lee, C. R. Gilbert, C. H. Hocutt, R. E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister, and J.

R. Stauffer, Jr. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes. North Carolina Biological

Survey Publication 1980-12. North Carolina State Museum of Natural History.

Herre, A. W. C. T. 1924. Distribution of the true freshwater fishes in the Philippines. II.

Philippine Labyrinthici, Clariidae, and Siluridae. Philippine Journal of Science

24(6):683–709.

Hugg, D. O. 1996. MAPFISH georeferenced mapping database. Freshwater and estuarine fishes

of North America. Life Science Software, Edgewater, Maryland.

IGFA. 2001. Database of IGFA angling records until 2001. IGFA, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

19

Joshi, R. C. No date. Invasive alien species (IAS): concerns and status in the Philippines.

Kotagama, S. W., and C. N. B. Bambaradeniya. 2006. An overview of the wetlands of Sri Lanka

and their conservation significance. IUCN Sri Lanka and the Central Environmental

Authority, National Wetland Directory of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Kottelat, M. 1998. Fishes of the Nam Theun and Xe Bangfai basins, Laos, with diagnoses of

twenty-two new species (Teleostei: Cyprinidae, Balitoridae, Cobitidae, Coiidae and

Odontobutidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 9(1):1–128.

Kottelat, M. 2001. Fishes of Laos. WHT Publications, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Kottelat, M., A. J. Whitten, S. N. Kartikasari, and S. Wirjoatmodjo. 1993. Freshwater fishes of

Western Indonesia and Sulawesi. Periplus Editions, Hong Kong.

Lee, D. S., C. R. Gilbert, C. H. Hocutt, R. E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister, and J. R. Stauffer, Jr.

1980 et seq. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes. North Carolina State Museum of

Natural History, Raleigh.

Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae, Ed. X. (Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum

classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus

I. Editio decima, reformata.) Holmiae.

Loftus, W. F. 1979. Synchronous aerial respiration by the walking catfish in Florida. Copeia

1979:156–158.

Loftus, W. F. 1988. Distribution and ecology of exotic fishes in Everglades National Park. Pages

24–34 in L. K. Thomas, editor. Proceedings of the 1986 conference on science in the

national parks, volume 5. Management of exotic species in natural communities. U.S.

National Park Service and George Wright Society, Washington, D.C.

Loftus, W. F., and J. A. Kushlan. 1987. Freshwater fishes of southern Florida. Bulletin of the

Florida State Museum of Biological Science 31(4):147–344.

Lorenz, J. J., C. C. McIvor, G. V. N. Powell, and P. C. Frederick. 1997. A drop net and

removable walkway used to quantitatively sample fishes over wetland surfaces in the

dwarf mangroves of the southern Everglades. Wetlands 17:346–359.

Minckley, W. L. 1973. Fishes of Arizona. Arizona Fish and Game Department. Sims Printing

Company, Phoenix, Arizona.

Nico, L. 2005a. Clarias batrachus Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville,

Florida.

20

Nico, L. G. 2005b. Changes in the fish fauna of the Kissimmee River basin, peninsular Florida:

non-native additions. Pages 523–556 in J. N. Rinne, R. M. Hughes, and B. Calamusso,

editors. Historical changes in large river fish assemblages of the Americas. American

Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Rahman, A. K. A. 1989. Freshwater fishes of Bangladesh. Zoological Society of Bangladesh.

Department of Zoology, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Rao, G. R. M., S. K. Singh, and A. K. Sahu. 1995. Fry and fingerling production of Clarias

batrachus (Linnaeus). Asian Journal of Zoological Science 4:7–10.

Robins, H. R. No date. Biological profiles walking catfish. Ichthyology at the Florida Museum of

Natural History. Available:

http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Gallery/Descript/WalkingCatfish/WalkingCatfish.html.

(July 2009).

Ros, W. 2004. Erfolgreiche Froschwels-Nachzucht im Aquarium. [Successful spawning of the

wonderful WanderWels, Clarias batrachus]. Datz 57(7):13–15. (In German.)

Ros, W. 2004c. Successful spawning of the wonderful WanderWels, Clarias batrachus. DATZ.

Available: http://www.planetcatfish.com/shanesworld.php?article_id=249. (August

2006).

Shafland, P. L., and J. M. Pestrak. 1982. Lower lethal temperatures for fourteen non-native fishes

in Florida. Environmental Biology of Fishes 7:139–156.

Shapovalov, L., A. J. Cordone, and W. A. Dill. 1981. A list of freshwater and anadromous fishes

of California. California Fish and Game 67(1):4–38.

Sokheng, C., C. K. Chhea, S. Viravong, K. Bouakhamvongsa, U. Suntornratana, N. Yoorong, N.

T. Tung, T. Q. Bao, A. F. Poulsen, and J. V. Jørgensen. 1999. Fish migrations and

spawning habits in the Mekong mainstream: a survey using local knowledge (basin-

wide). Assessment of Mekong fisheries: Fish Migrations and Spawning and the Impact of

Water Management Project (AMFC). AMFP Report 2/99. Vientiane, Lao P.D.R.

Taki, Y. 1974. Fishes of the Lao Mekong Basin. United States Agency for International

Development, Mission to Laos Agriculture Division.

Taki, Y. 1978. An analytical study of the fish fauna of the Mekong basin as a biological

production system in nature. Research Institute of Evolutionary Biology Special

Publications 1, Tokyo.

Talwar, P. K., and A. G. Jhingran. 1991. Inland fishes of India and adjacent countries. 2

volumes. Oxford & IBH Publishing, New Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta.

21

Talwar, P. K., and A. G. Jhingran, editors. 1992. Inland fishes of India and adjacent countries. A.

A. Balkema, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Taylor, J. N., W. R. Courtenay, Jr., and J. A. McCann. 1984. Known impact of exotic fishes in

the continental United States. Pages 322–373 in W. R. Courtenay, Jr., and J. R. Stauffer,

editors. Distribution, biology, and management of exotic fish. Johns Hopkins Press,

Baltimore, Maryland.

Teugels, G. G., R. C. Diego, L. Pouyaud, and M. Legendre. 1999. Redescription of Clarias

macrocephalus (siluriformes: Clariidae) from Southeast Asia. Cybium 23:285–295.

Tilmant, J. T. 1999. Management of nonindigenous aquatic fish in the U.S. National Park

System. National Park Service.

Ukkatawewat, S. 2005. The taxonomic characters and biology of some important freshwater

fishes in Thailand. National Inland Fisheries Institute, Department of Fisheries, Ministry

of Agriculture, Bangkok, Thailand.

USFWS (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). 2005. National Wildlife Refuge System invasive

species. Available: http://www.nwrinvasives.com/index.asp. (2006).

Vidthayanon, C. 2002. Peat swamp fishes of Thailand. Office of Environmental Policy and

Planning, Bangkok, Thailand.

Vinyard, G. L. 2001. Fish species recorded from Nevada. Biological Resources Research Center.

University of Nevada, Reno.

Whitworth, W. R. 1996. Freshwater fishes of Connecticut. State Geological and Natural History

Survey of Connecticut, Bulletin 114.