CREATED BY

EASTERN MASSASAUGA RATTLESNAKE

SPECIES SURVIVAL PLAN

®

IN ASSOCIATION WITH

AZA SNAKE TAXON ADVISORY GROUP

EASTERN

MASSASAUGA

RATTLESNAKE

(Sistrurus catenatus

catenatus)

CARE MANUAL

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

2

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare

Committee

Formal Citation:

AZA Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake SSP (2013). Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus

catenatus catenatus) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring: MD.

Original Completion Date:

July 2013

Authors and Significant contributors:

Andrew M. Lentini, PhD, Toronto Zoo

Joanne Earnhardt, PhD, Lincoln Park Zoo, Former AZA Eastern Massasauga SSP Coordinator

Reviewers:

Mike Maslanka, Smithsonian National Zoo

Randy Junge, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium

Jeff Jundt, Detroit Zoo

Mike Redmer, US Fish and Wildlife Service

Bob Johnson, Toronto Zoo

Fred Antonio, Orianne Society

AZA Staff Editors:

Debborah Colbert, PhD, Vice President, Animal Conservation

Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director, Animal Programs & Science

Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editor

Cover Photo Credits:

K. Ardill

Disclaimer:

This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts

based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. The manual assembles

basic requirements, best practices, and animal care recommendations to maximize capacity for

excellence in animal care and welfare. The manual should be considered a work in progress, since

practices continue to evolve through advances in scientific knowledge. The use of information within this

manual should be in accordance with all local, state, and federal laws and regulations concerning the

care of animals. While some government laws and regulations may be referenced in this manual, these

are not all-inclusive nor is this manual intended to serve as an evaluation tool for those agencies. The

recommendations included are not meant to be exclusive management approaches, diets, medical

treatments, or procedures, and may require adaptation to meet the specific needs of individual animals

and particular circumstances in each institution. Commercial entities and media identified are not

necessarily endorsed by AZA. The statements presented throughout the body of the manual do not

represent AZA standards of care unless specifically identified as such in clearly marked sidebar boxes.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

3

Table of Contents

Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 5

Taxonomic Classification ........................................................................................................ 5

Genus, Species, and Status ................................................................................................... 5

General Information ............................................................................................................... 5

Chapter 1. Ambient Environment ............................................................................................ 7

1.1 Temperature and Humidity ............................................................................................... 7

1.2 Light ................................................................................................................................. 8

1.3 Water and Air Quality ....................................................................................................... 8

1.4 Sound and Vibration ......................................................................................................... 8

Chapter 2. Habitat Design and Containment .........................................................................10

2.1 Space and Complexity ....................................................................................................10

2.2 Safety and Containment ..................................................................................................12

Chapter 3. Transport ...............................................................................................................15

3.1 Preparations ....................................................................................................................15

3.2 Protocols .........................................................................................................................16

Chapter 4. Social Environment ..............................................................................................18

4.1 Group Structure and Size ................................................................................................18

4.2 Influence of Others and Conspecifics ..............................................................................18

4.3 Introductions and Reintroductions ...................................................................................18

Chapter 5. Nutrition.................................................................................................................19

5.1 Nutritional Requirements .................................................................................................19

5.2 Diets ................................................................................................................................19

5.3 Nutritional Evaluations .....................................................................................................20

Chapter 6. Veterinary Care .....................................................................................................21

6.1 Veterinary Services .........................................................................................................21

6.2 Identification Methods .....................................................................................................22

6.3 Transfer Examination and Diagnostic Testing Recommendations ...................................23

6.4 Quarantine ......................................................................................................................23

6.5 Preventive Medicine ........................................................................................................26

6.6 Capture, Restraint, and Immobilization ............................................................................28

6.7 Management of Diseases, Disorders, Injuries and/or Isolation ........................................31

Chapter 7. Reproduction ........................................................................................................35

7.1 Reproductive Physiology and Behavior ...........................................................................35

7.2 Assisted Reproductive Technology .................................................................................35

7.3 Pregnancy and Birth ........................................................................................................36

7.4 Birthing Facilities .............................................................................................................36

7.5 Assisted Rearing .............................................................................................................36

7.6 Contraception ..................................................................................................................37

Chapter 8. Behavior Management ..........................................................................................38

8.1 Animal Training ...............................................................................................................38

8.2 Environmental Enrichment ..............................................................................................38

8.3 Staff and Animal Interactions ...........................................................................................39

8.4 Staff Skills and Training ...................................................................................................39

Chapter 9. Program Animals ..................................................................................................40

9.1 Program Animal Policy ....................................................................................................40

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

4

9.2 Institutional Program Animal Plans ..................................................................................41

9.3 Program Evaluation .........................................................................................................42

Chapter 10. Research .............................................................................................................43

10.1 Known Methodologies ...................................................................................................43

10.2 Future Research Needs ................................................................................................44

Chapter 11. Confiscations ......................................................................................................46

11.1 Confiscations .................................................................................................................46

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................47

References ..............................................................................................................................48

Appendix A: Accreditation Standards by Chapter ................................................................51

Appendix B: Acquisition/Disposition Policy .........................................................................54

Appendix C: Recommended Quarantine Procedures ..........................................................58

Appendix D: Program Animal Policy and Position Statement .............................................60

Appendix E: Developing an Institutional Program Animal Policy .......................................64

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

5

Introduction

Preamble

AZA accreditation standards, relevant to the topics discussed in this manual, are highlighted in boxes

such as this throughout the document (Appendix A).

AZA accreditation standards are continuously being raised or added. Staff from AZA-accredited

institutions are required to know and comply with all AZA accreditation standards, including those most

recently listed on the AZA website (http://www.aza.org) which might not be included in this manual.

Taxonomic Classification

Table 1. Taxonomic classification for eastern massasauga rattlesnake

Classification

Taxonomy

Kingdom

Animalia

Phylum

Chordata

Class

Sauropsida

Order

Squamata

Suborder

Serpentes

Family

Viperidae

Genus, Species, and Status

Table 2. Genus, species, and status information for eastern massasauga rattlesnake

Genus

Species

Common Name

USA

Status

IUCN Status

AZA Status

Sistrurus

catenatus

Eastern Massasauga

Rattlesnake

--

--

SSP

General Information

The information contained within this Animal Care Manual (ACM) provides a compilation of animal

care and management knowledge that has been gained from recognized species experts, including AZA

Taxon Advisory Groups (TAGs), Species Survival Plan

®

Programs (SSPs), Studbook Programs,

biologists, veterinarians, nutritionists, reproduction physiologists, behaviorists and researchers. They are

based on the most current science, practices, and technologies used in animal care and management

and are valuable resources that enhance animal welfare by providing information about the basic

requirements needed and best practices known for caring for ex situ Eastern massasauga rattlesnake

populations. This ACM is considered a living document that is updated as new information becomes

available and at a minimum of every five years.

Information presented is intended solely for the education and training of zoo and aquarium personnel

at AZA-accredited institutions. Recommendations included in the ACM are not exclusive management

approaches, diets, medical treatments, or procedures, and may require adaptation to meet the specific

needs of individual animals and particular circumstances in each

institution. Statements presented throughout the body of the

manuals do not represent specific AZA accreditation standards of

care unless specifically identified as such in clearly marked

sidebar boxes. AZA-accredited institutions which care for Eastern

massasauga rattlesnake must comply with all relevant local,

state, and federal wildlife laws and regulations; AZA accreditation

standards that are more stringent than these laws and regulations

must be met (AZA Accreditation Standard 1.1.1).

The ultimate goal of this ACM is to facilitate excellent eastern massasauga rattlesnake management

and care, which will ensure superior eastern massasauga rattlesnake welfare at AZA-accredited

institutions. Ultimately, success in our eastern massasauga rattlesnake management and care will allow

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.1.1) The institution must comply with all

relevant local, state, and federal wildlife

laws and regulations. It is understood

that, in some cases, AZA accreditation

standards are more stringent than

existing laws and regulations. In these

cases the AZA standard must be met.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

6

AZA-accredited institutions to contribute to Eastern massasauga rattlesnake conservation, and ensure

that eastern massasauga rattlesnakes are in our future for generations to come.

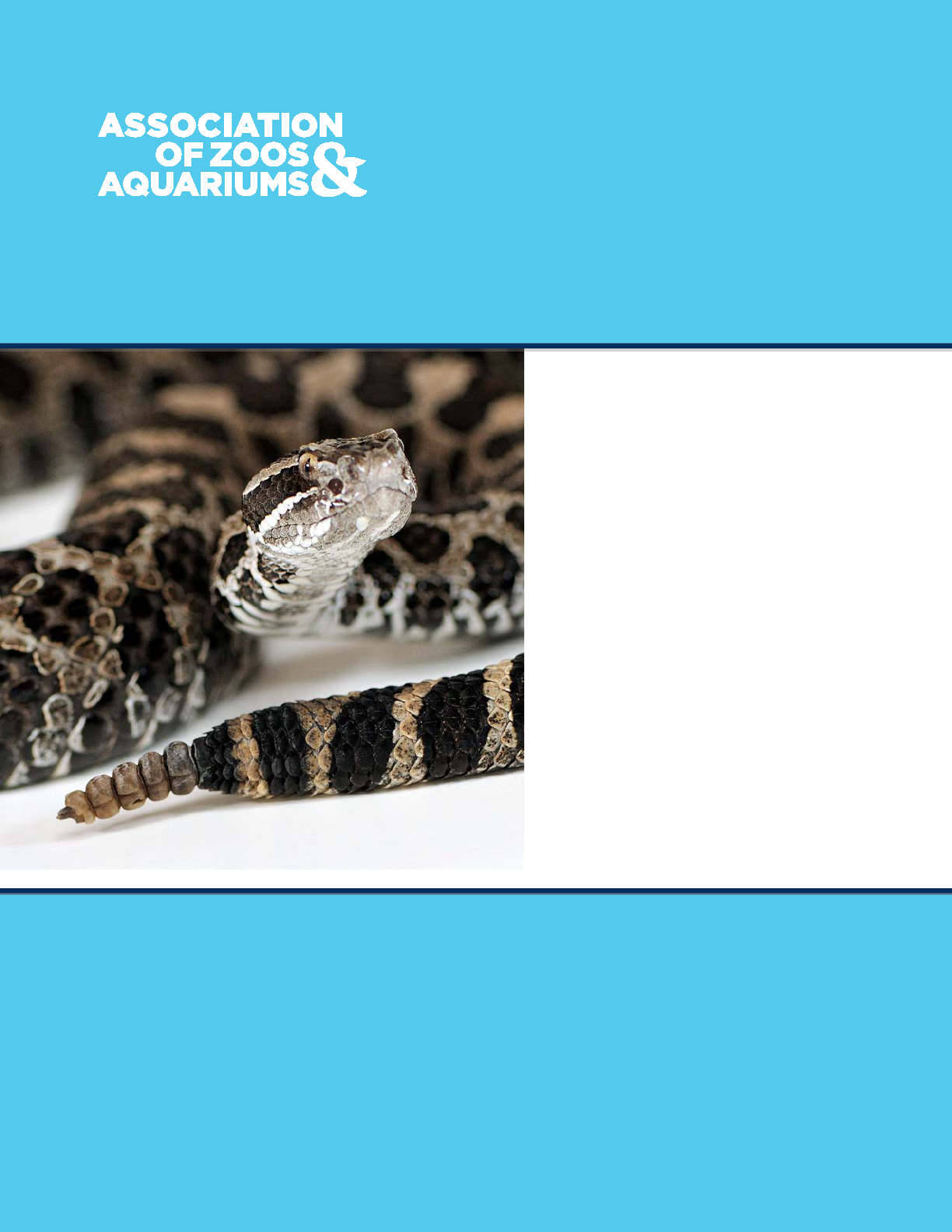

The eastern massasauga rattlesnake is a small stout rattlesnake (47.2–76 cm) that is found in

Ontario, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and

Missouri (Conant & Collins, 1991). The typical pattern of the massasauga consists of dark brown blotches

on the back and three rows of alternating blotches on the side over a grey background.

The massasauga is a member of the pit viper subfamily, the Crotalinae (Family Viperidae). The pit

vipers are venomous snakes that possess paired heat sensing facial pits located slightly below, and

between the eye and the nostril (Klauber, 1956). Neural signals from the spatial arrangement of infrared

receptors in the pit organs are integrated with visual information in the brain’s tectum, suggesting that the

pit organs are infrared imaging devices rather than simple thermal receptors. The pit organs are

exceptionally sensitive and respond to thermal radiation and allow the snake to detect thermal differences

between an object and its surroundings of 0.003–0.005 °C (32 °F) (Bullock & Diecke, 1956). Facial pits

are used to aid in prey acquisition and may also play a role in defensive behavior and in thermoregulatory

behavior (Krochmal & Bakken, 2003).

Rattle: The characteristic rattle is composed of interlocking rings of keratin (stratum corneum) at the end

of the tail. Each time the snake sheds its skin, a new segment is added to the rattle. Specialized tail

muscles vibrate the rattle at a rate of 20–100 Hz thus producing the distinctive buzzing sound from 2–20

kHz (Klauber, 1956; Fenton & Licht, 1990). The primary function of the rattle is defensive. Klauber (1956)

documented a multi-layered pattern of behavior when a rattlesnake is disturbed. He described how a

snake remains silent; relying on crypsis to remain undetected even when a potential threat is only a short

distance away. Once the rattlesnake has been disturbed, it will begin to rattle. If the disturbance

continues, the snake will try to retreat. If the disturbance or perceived threat is imminent and retreat is not

possible, it will change its posture and adopt the characteristic S-shape that readies it for a strike. This

escalating pattern of behavioral response to a threat illustrates that rattlesnakes are shy snakes and

prefer to remain motionless and undetected in order to avoid harm.

Status: The massasauga is considered a species at risk of extinction and is listed as Endangered,

Threatened, or Of Special Concern throughout its range. In Canada, massasaugas were listed as a

threatened species by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in 1991 (Beltz, 1993). The

massasauga is the only extant venomous snake found in Ontario and has been the subject of a

comprehensive conservation and education effort in the province since the late 1980s (Johnson, 1993). In

the United States it is a Candidate Species (United States Fish and Wildlife Service, 2012). It is listed as

Endangered in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin;

and of Special Concern in Michigan.

Conservation: This high profile species has also been the focus of ongoing research into its ecology and

natural history throughout its range. The results of this research are used by wildlife managers to optimize

land management practices, improve habitat, and potentially affect the recovery of this species (Jaworski,

1993; Johnson & Breisch, 1999; Kingsbury, 1999; Reinert & Bushar, 1993).

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

7

Chapter 1. Ambient Environment

1.1 Temperature and Humidity

Animal collections within AZA-accredited institutions must be

protected from weather detrimental to their health (AZA

Accreditation Standard 1.5.7). Animals not normally exposed to

cold weather/water temperatures should be provided heated

enclosures/pool water. Likewise, protection from excessive cold

weather/water temperatures should be provided to those animals normally living in warmer climates/water

temperatures.

Temperature is one of the most important factors affecting living organisms, particularly for

ectotherms such as reptiles. Temperature influences metabolic rate by affecting not only the rate of

various biochemical reactions, it also affects the cellular environment in which they take place. For the

most part, animals regulate body temperature to limit the disrupting effects of temperature variation. The

majority of endothermic and ectothermic vertebrates appear to differ only in the degree of temperature

homeostasis (Hutchinson et al., 1979; Varghese & Pati, 1996). Thermoregulation is essential to many

physiological and ecological processes in ectothermic vertebrates. Body temperature directly affects

fitness by influencing metabolic rate, which in turn has an effect on foraging, feeding, energy use, and can

also influence other biological processes such as growth, development, reproduction and healing.

Thermoregulation is achieved by both physiological and behavioral means. Behavioral

thermoregulation is a low energy means of controlling Tb using refined behavior patterns that regulate the

intake and loss of heat.

Massasauga rattlesnakes, as ectothermic vertebrates, by definition, rely almost exclusively on

behavioral thermoregulation to obtain heat required to maintain Tb from their environment. The exhibit

environment should therefore provide massasauga rattlesnakes with the thermal landscape to allow for

behavioral thermoregulation.

An ambient temperature range of 22–32 °C (71–90 °F) should be offered, with a specific hot spot

(30–34 °C [86–93 °F]). This will provide a thermal gradient that allows the snake to select desired

temperatures for proper behavior thermoregulation. Each holding area should have a thermometer to

monitor changes in temperature. A humidity of 50–70% is desirable. Natural substrates also help increase

humidity, which is important for ecdysis.

During winter months, ambient temperatures can drop to 18–22 °C (64–71 °F) in the enclosure, but a

basking spot should still be available. Temperatures can be further lowered in order to simulate

hibernation/brumation. Such cooling can be potentially dangerous for snakes and care should be

exercised when cooling snakes for extended periods. Hibernation protocols are variable, however

animals should be in good condition, clinically healthy, and well hydrated before they are put into

hibernation. They should be maintained in an environment with sufficient humidity and should have

access to water (Dutton & Taylor, 2003). Blood samples should be collected on arousal for measuring

plasma uric acid levels, and if levels are high, fluid therapy should be implemented.

A common feature of natural hibernation sites across the

range seems to be access to the unfrozen portion of the water

table (Johnson, 1995). A high humidity hibernation environment

reduces the dehydrating effects of cool air. However, substrates

should not be wet with hibernating massasaugas, since this may

increase the likelihood of skin infection. A shallow water dish

large enough for the snake to soak in should be provided. Wild

massasaugas have been reported to hibernate submerged in

water this may be a strategy to prevent dehydration or buffer

temperature changes. In zoos and aquariums, hibernating snakes

offered a water bowl, will occasionally submerge in the water

during hibernation. This may be a mechanism that aids in

avoiding dehydration. At low temperatures snakes will be unable

to digest food. Therefore, snakes should be fasted for 2–3 weeks

prior to cooling in order to ensure their digestive tract is empty

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.5.7) The animal collection must be

protected from weather detrimental to

their health.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(10.2.1) Critical life-support systems for

the animal collection, including but not

limited to plumbing, heating, cooling,

aeration, and filtration, must be equipped

with a warning mechanism, and

emergency backup systems must be

available. All mechanical equipment

should be under a preventative

maintenance program as evidenced

through a record-keeping system. Special

equipment should be maintained under a

maintenance agreement, or a training

record should show that staff members

are trained for specified maintenance of

special equipment.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

8

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.5.9) The institution must have a regular

program of monitoring water quality for

collections of fish, pinnipeds, cetaceans,

and other aquatic animals. A written

record must be maintained to document

long-term water quality results and

chemical additions.

before temperatures are lowered.

AZA institutions with exhibits which rely on climate control must have critical life-support systems for

the animal collection and emergency backup systems available, while all mechanical equipment should

be included in a documented preventative maintenance program. Special equipment should be

maintained under a maintenance agreement or records should indicate that staff members are trained to

conduct specified maintenance (AZA Accreditation Standard 10.2.1).

Environmental control (i.e., heating and air-conditioning) should be maintained as per the individual

institution’s standard operating procedures. Since appropriate temperature is vital to the well being of

massasauga rattlesnakes, heating and cooling systems should be monitored throughout the day by

appropriate staff (e.g., animal care staff, maintenance staff, security, etc.).

1.2 Light

Careful consideration should be given to the spectral, intensity, and duration of light needs for all

animals in the care of AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums. The use of quality lighting will help meet the

physiological requirements of snakes and promotes natural behavior. Quality lighting also allows for

thermoregulation, promotes plant growth and contributes to exhibit aesthetics.

General lighting for holding cages can be provided by 40-watt double strip fluorescent light fixture

suspended approximately 20 cm (7.8 in.) above holding cages. Using a black light or similar UV

producing bulb in this setup will provide low intensity UV for snakes housed in small holding tanks.

Exhibit lighting can be used to provide good quality light, heat and UV. Basking sites can be provided

using incandescent lamps, ceramic heat emitters or substrate heaters. UV lighting selection should be

based on the size of the exhibit and the distance the lamps are from the animals and can be evaluated

using a UV meter. See Burger et al. (2007), Gehrmann (1987) and Gehrmann et al. (2004) for details on

the use of UV lighting in reptile husbandry.

The photoperiod should mimic the natural photoperiod experienced by massasauga. During winter,

the photophase should be 9 hours and the scotophase 15 hours. During summer, the photophase should

be 15 hours and scotophase 9 hours.

1.3 Water and Air Quality

AZA-accredited institutions must have a regular program of

monitoring water quality for collections of aquatic animals and a

written record must document long-term water quality results and

chemical additions (AZA Accreditation Standard 1.5.9). Monitoring

selected water quality parameters provides confirmation of the

correct operation of filtration and disinfection of the water supply

available for the collection. Additionally, high quality water

enhances animal health programs instituted for aquatic

collections.

Fresh water should be offered daily. Large water bowls or pools that allow the snake to fully

submerge should be provided. Periodic heavy misting and soaking will be beneficial to encourage

drinking and increase humidity. Depending on the exhibit or holding set-up, heavy misting can be done

every 3–10 days. When misting heavily, ensure that the environment dries out thoroughly within 48–72

hours to avoid potential skin and respiratory infections.

Air exchange rates required in reptile exhibits and holdings are much lower than those recommended

for mammals. Excessive air exchange rates can lead to problems maintaining adequate temperature and

humidity for reptiles. Draft-free air exchanges in the range of 2–8 per hour should be sufficient for rooms

containing massasaugas.

1.4 Sound and Vibration

Consideration should be given to controlling sounds and vibrations that can be heard by animals in

the care of AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums. Snakes are able to detect both airborne and ground-

borne vibrations using both the body surface and inner ear; however snakes appear to be more sensitive

to ground-borne vibrations (Young, 2003). Although snakes have a limited auditory sensitivity range from

approximately 50–1,000 Hz compared to human hearing of 15–18,000 Hz (Wever, 1978), prolonged

exposure to excessive noise and vibration should be avoided.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

9

Potential sources of sound/vibration that may pose a problem include pumps or compressors

mounted near a holding or exhibit area. Such equipment should not be installed near in close proximity to

rattlesnake housing. Portable holding and exhibit tanks can be placed on a cushioning material such as

foam rubber or rigid foam (expanded polystyrene) insulation in order to minimize the effects of vibrations.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

10

Chapter 2. Habitat Design and Containment

2.1 Space and Complexity

Careful consideration should be given to exhibit design so

that all areas meet the physical, social, behavioral, and

psychological needs of the species. Animals should be displayed,

whenever possible, in exhibits replicating their wild habitat and in

numbers sufficient to meet their social and behavioral needs (AZA

Accreditation Standard 1.5.2).

Holding enclosures used to house massasaugas should be at

least as long as the snake and half as wide. The enclosure should

offer adequate ventilation. A simple shelter or hide box should be available as a secure hiding place. A

simple, easily removable substrate (e.g., newspaper) is suitable for off-exhibit housing. Natural substrates

including sand, soil, mulch, coconut husks/coir, and leaf litter are often used in exhibits. Snakes, which

will be kept in zoos indefinitely, should have access to a larger space in which a normal array of behavior

may occur.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.5.2) Animals should be displayed,

whenever possible, in exhibits replicating

their wild habitat and in numbers sufficient

to meet their social and behavioral needs.

Display of single specimens should be

avoided unless biologically correct for the

species involved.

Figure 2. Massasauga in a naturalistic setting and off-exhibit holdings. The exhibit

measures 91.4 cm x 116.8 cm x 106.7 cm (36 in. x 46 in. x 42 in.). Lighting, heat, and

UV elements are provided by fluorescent and incandescent or halogen lighting from

above. Fresh water trickles through the water feature nonstop. The off-exhibit enclosure

is the same as those described for hibernation utilizing fluorescent strip lights from

above the enclosure.

Photos courtesy of J. Jundt

Figure 1. Examples of on-exhibit and off-exhibit housing for massasaugas.The display tank on the left is 61 cm x 30.5

cm x 31.8 cm (24 in. x 12 in. x 12.5 in.). It has both fluorescent (20 W) and halogen (18 W) lighting. The off-exhibit

holding area is a standard polycarbonate box with a mesh lid and lock.

Photos courtesy of Y. Clippinger

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

11

Figure 3. A mixed species snake exhibit. This zoo houses a massasauga with a timber rattlesnake.

They use small river rock as a substrate, adding leaf litter in the fall. The enclosure is heated from

above with one infrared 250 W bulb. Lighting is provided by incandescent room lighting and

supplemented with a 60 cm (24 in.) fluorescent light above the enclosure. The enclosure's internal

dimensions are 138 cm x 96.5 cm x 155 cm (54.5 in. x 38 in. x 61 in.).

Photos courtesy of B. Harrison

Figure 4. A planted multispecies massasaugas exhibit. Massasaugas at this zoo are exhibited in a multi-species

enclosure together with Pituophis catenifer sayi, Elaphe vulpina vulpine, and Terrapene ornata. The enclosure is

constructed of fiberglass and measures 72 cm x 48 cm x 48 cm (6 ft x 4 ft x 4 ft). The substrate consists of a

sand/gravel mixture. The plantings consist of grasses and native prairie perennial flowers. Lighting is provided

by two eight-foot long dual fluorescent light fixtures equipped with cool white bulbs. Heat and UV are provided

via a 160 W Active UV bulb.

Photos courtesy of M. Wanner

Figure 5. Off-exhibit massasauga enclosures. Massasaugas maintained off-exhibit in Neodesha ABS

enclosures. The overall dimensions of the enclosure are 122 cm x 61 cm x 46 cm (4 ft x 2 ft x 1.5 ft) and it is

divided into two units. Carefresh

®

recycled newspaper bedding is used as substrate and each unit is provided

with rocks, a hide box, and a water bowl. Lighting consists of a double T12 48 in. shop light with two Verilux

bulbs. Flexwatt heat affixed to the bottom of the enclosure can be utilized for supplementary heat.

Photos courtesy of J. Adamski

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

12

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.5.3) Institutions maintaining

potentially dangerous animals (e.g. large

carnivores, large reptiles, medium to large

primates, large hoofstock, killer whales,

sharks, venomous animals, and others,

etc.) must have appropriate safety

procedures in place to prevent attacks

and injuries by these animals. Appropriate

response procedures must also be in

place to deal with an attack resulting in an

injury. These procedures must be

practiced routinely per the emergency drill

requirements contained in these

standards. Whenever injuries result from

these incidents, a written account

outlining the cause of the incident, how

the injury was handled, and a description

of any resulting changes to either the

safety procedures or the physical facility

must be prepared and maintained for five

years from the date of the incident.

The same careful consideration regarding exhibit size and

complexity and its relationship to the massasauga’s overall well-

being must be given to the design and size all enclosures,

including those used in exhibits, holding areas, hospital, and

quarantine/isolation (AZA Accreditation Standard 10.3.3).

It is recommended that short term holding enclosures used to

house a snake should be at least 30 cm x 60 cm x 30 cm (11.8

in. x 24 in. 11.8 in.) high. The top of the container should be

screened to offer adequate ventilation. A simple shelter or hide

box should be available as a secure hiding place. A simple,

easily removable substrate (e.g., newspaper) is suitable for off-

exhibit housing.

2.2 Safety and Containment

Massasauga rattlesnakes are venomous animals that are not

suitable for free range exhibits where they will be in contact with

the visiting public. AZA-accredited institutions that care for

potentially dangerous animals, such as venomous snakes, must

have appropriate safety procedures in place to prevent attacks

and injuries by these animals and appropriate response

procedures must also be in place to deal with an attack resulting

in an injury (AZA Accreditation Standard 11.5.3).

All emergency safety procedures must be clearly written,

provided to appropriate staff and volunteers, and readily

available for reference in the event of an actual emergency (AZA

Accreditation Standard 11.2.4). AZA-accredited institutions must

have a communication system that can be quickly accessed in

case of an emergency (AZA Accreditation Standard 11.2.6).

AZA-accredited institutions must also ensure that written

protocols define how and when local police or other emergency

agencies are contacted and specify response times to

emergencies (AZA Accreditation Standard 11.2.7)

Staff training for emergencies must be undertaken and

records of such training maintained. Security personnel must be

trained to handle all emergencies in full accordance with the

policies and procedures of the institution and in some cases, may

be in charge of the respective emergency (AZA Accreditation Standard 11.6.2). Animal injury emergency

response drills must be practiced routinely to ensure that the institution’s staff know their duties and

AZA Accreditation Standard

(10.3.3) All animal enclosures (exhibits,

holding areas, hospital, and

quarantine/isolation) must be of a size

and complexity sufficient to provide for

the animal’s physical, social, and

psychological well-being; and exhibit

enclosures must include provisions for the

behavioral enrichment of the animals.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.2.4) All emergency procedures must

be written and provided to staff and,

where appropriate, to volunteers.

Appropriate emergency procedures must

be readily available for reference in the

event of an actual emergency. These

procedures should deal with four basic

types of emergencies: fire,

weather/environment; injury to staff or a

visitor; animal escape.

Figure 6. Naturalistic exhibit for massasaugas. This massasauga exhibit is approximately 3 m x 1 m x 1.5 m (10 ft

x 3 ft x 5 ft), and is setup to represent the exposed bedrock of Georgian Bay region of Canada. Substrate is

coconut husk and mulch. Natural rocks, logs, and artificial plants are used for decoration and shelter. Lighting is

provided by fluorescent and halogen bulbs.

Photos courtesy of C. Cox

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

13

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.5.2) All areas housing venomous

animals, or animals which pose a serious

threat of catastrophic injury and/or death

(e.g. large carnivores, large reptiles,

medium to large primates, large

hoofstock, killer whales, sharks,

venomous animals, and others, etc.) must

be equipped with appropriate alarm

systems, and/or have protocols and

procedures in place which will notify staff

in the event of a bite injury, attack, or

escape from the enclosure. These

systems and/or protocols and procedures

must be routinely checked to insure

proper functionality, and periodic drills

must be conducted to insure that

appropriate staff members are notified

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.2.5) Live-action emergency drills must

be conducted at least once annually for

each of the four basic types of emergency

(fire; weather/environment appropriate to

the region; injury to staff or a visitor;

animal escape). Four separate drills are

required. These drills must be recorded

and evaluated to determine that

procedures are being followed, that staff

training is effective, and that what is

learned is used to correct and/or improve

the emergency procedures. Records of

these drills must be maintained and

improvements in the procedures

documented whenever such are

identified.

responsibilities and know how to handle venomous bite

emergencies properly if they occur. All drills need to be recorded

and evaluated to ensure that procedures are being followed, that

staff training is effective, and that what is learned is used to

correct and/or improve the emergency procedures. Records of

these drills must be maintained and improvements in the

procedures duly noted whenever such are identified (AZA

Accreditation Standard 11.2.5).

Individual institutions should develop and follow their own

emergency and dangerous animal policies. Venomous reptile

procedures are very specific to each institution depending on

staff availability, training and even local and provincial/state

health and safety regulations (e.g., each institution should have

its own alarm system, response protocol, lock-out protocol, etc.).

Animal exhibits and holding areas in all AZA-accredited

institutions must be secured to prevent unintentional animal

egress (AZA Accreditation Standard 11.3.1). Exhibits in which

the visiting public is not intended to have contact with animals,

such as with the massasauga rattlesnake, some means of

deterring public contact with animals must be in place (AZA

Accreditation Standard 11.3.6).

Holding and exhibit areas housing venomous snakes should

be clearly labeled as such. Containers and snake areas should

be labeled and list the species (scientific and common name)

and number of animals present. All animal exhibits and holding

areas must be secured to prevent unintentional animal egress

(AZA Accreditation Standard 11.3.1), therefore, exhibit design

must be considered carefully because all snakes are capable of

squeezing through very narrow openings. Furthermore,

massasaugas are livebearers, therefore enclosures should not

have any gaps or holes over 3 mm (1/8 in.) that could serve as

escape routes for neonates. Any potential escape routes (e.g.,

ventilation, plumbing, door jams, etc.) should be sealed. All

holding containers should be secure and holding and exhibit

areas should be kept locked with restricted access. Emergency

lighting is also necessary in the event of a power outage.

All areas housing venomous snakes must be equipped with

appropriate alarm systems, and/or have protocols and

procedures in place which will notify staff in the event of a bite

injury, attack, or escape from the enclosure. These systems

and/or protocols and procedures must be routinely checked to

insure proper functionality, and periodic drills must be conducted

to ensure that appropriate staff members are notified (AZA

Accreditation Standard 11.5.2).

Minimizing the possibility of snakebite can be achieved by

restricting access to venomous snake areas to those who have

received training in handling and working around venomous

snakes. Further, adequate handling equipment such as snake

hooks, capture tongs, catch boxes, transport boxes, restraint

tubes, and holding cages should be available. A two-person

policy that ensures backup staff is available during hands on

restraint or handling is common in many institutions.

Procedures to deal with snakebite should be established and

posted in all areas where venomous snakes are kept. These

include an emergency response system (i.e., a reliable alarm

system) and written response procedure that contains contact

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.3.1) All animal exhibits and holding

areas must be secured to prevent

unintentional animal egress.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.3.6) In areas where the public is not

intended to have contact with animals,

some means of deterring public contact

with animals (e.g., guardrails/barriers)

must be in place.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.6.2) Security personnel, whether staff

of the institution, or a provided and/or

contracted service, must be trained to

handle all emergencies in full accordance

with the policies and procedures of the

institution. In some cases, it is recognized

that Security personnel may be in charge

of the respective emergency (i.e.,

shooting teams).

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.2.7) A written protocol should be

developed involving local police or other

emergency agencies and include

response times to emergencies.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

14

phone numbers for supervisory staff and emergency services. The

snakebite procedure should be tested on a regular basis.

It is the responsibility of the institution to verify that

appropriate antivenins are available locally for all venomous

species maintained at their institution, and for which antivenin is

produced. Institutions may rely on the antivenin supply of local

hospitals and treatment facilities, but it is also the institution’s

responsibility to guarantee that these inventories are maintained

adequately. Such arrangements must be documented (AZA

Accreditation Standard 11.5.1).

AZA Accreditation Standard

(11.5.1) Institutions maintaining

venomous animals must have appropriate

antivenin readily available, and its

location must be known by all staff

members working in those areas. An

individual must be responsible for

inventory, disposal/replacement, and

storage of antivenin

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

15

Chapter 3. Transport

3.1 Preparations

Animal transportation must be conducted in a manner that

adheres to all laws, is safe, and minimizes risk to the animal(s),

employees, and general public (AZA Accreditation Standard

1.5.11). Safe animal transport requires the use of appropriate

conveyance and equipment that is in good working order.

Cloth bags are commonly used to contain snakes. Since

snakes can deliver a bite through a cloth bag, transporting

venomous snakes in cloth bags alone is not recommended. An

additional level of containment should be used. Placing a snake bag in a secure box or crate will ensure

the safe transport of the animal.

Snake bags should be as large as possible (king size pillow cases work well). Snake bags should be

carefully inspected for wear and tear (i.e., holes) prior to use. Snakes should not be transported in cages

with heavy items (e.g., decorative rocks, water bowls) that might shift and cause injury.

The equipment s provide for the adequate containment, life support, comfort, temperature control,

food/water, and safety of the animal(s). The IATA Live Animals Regulations set a worldwide standard for

the transport of venomous snakes. These specify a triple containment of venomous snakes. Translucent

snake bags are available that allow for visual inspection of an animal. The snake bag containing the

snake should be securely closed (i.e., tied knot further secured with a cable tie). The bag should then be

placed in a clear container—to allow for inspection—and then placed within a labeled crate.

Containers should be ventilated, and if exposed to temperature extremes (i.e., direct sun or winter

chill) they should be insulated. Ventilation holes should be small enough (or covered with fine mesh) to

prevent the snake from biting through the hole and to prevent the escape of any newborn snakes.

Safe transport also requires the assignment of an adequate number of appropriately trained

personnel (by institution or contractor) who are equipped and prepared to handle contingencies and/or

emergencies that may occur in the course of transport. Planning and coordination for animal transport

requires good communication among all affected parties, plans for a variety of emergencies and

contingencies that may arise, and timely execution of the transport. At no time should the animal(s) or

people be subjected to unnecessary risk or danger.

A two-person policy that ensures backup staff is available during hands on restraint or handling is

common in many institutions.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.5.11) Animal transportation must be

conducted in a manner that is safe, well-

planned and coordinated, and minimizes

risk to the animal(s), employees, and

general public. All applicable local, state,

and federal laws must be adhered to.

Figure 7. A transport box for venomous snakes.

Photo courtesy of C. Cox

3.2 Protocols

Transport protocols should be well defined and clear to all animal care staff.

Bagging: When placing a snake in a snake bag, the bag should not be held open by hand. The bag

should be held open using Pilstrom tongs (i.e., long handled animal tongs), by a specially designed snake

bagging system (e.g., Midwest Tongs), or by draping the bag over a bucket. Once the snake has been

transferred to the bag with a snake hook or tong, the snake should be isolated at the bottom of the bag so

that the bag can be knotted shut. There are different techniques available for this.

If using a bag and tongs or a bagging system, place the bag with the snake in it on a flat surface and

isolate a snake at the bottom of the bag in order to tie it. This is accomplished by laying a long solid object

(e.g., broom handle, snake hook, etc.) across the bag so that the snake cannot crawl beneath this barrier

to the open end of the bag. Slide the barrier towards the rear of the bag so that the snake is isolated as

far as possible from the end where hands are tying a knot.

If using a bucket, the snake can be isolated at the bottom of the bag by pulling the open end of the

bag across the bucket lip and placing a lid on the bucket over the bag creating a barrier that the snake

cannot pass. The open end of the bag will be outside the bucket where it can be knotted safely.

To untie the bag, these procedures should be reversed so that the snake will be isolated at one end

of the bag while the knot is untied. To facilitate the release of a snake from a bag, the corners can be

sewn to create “hot corners.” This provides a rounded bottom to the bag and leaves material at the

corners that can be grasped with tongs when releasing a snake. See Figures 8–10 for details.

Figure 8. Bagging a massasauga. Using a bag, a bucket, a snake

hook, and tongs to restrain a massasauga.

Photo courtesy of C. Cox

Figure 9. Securing a massasauga. Knotting the bag while using the

hook to isolate the snake’s movement.

Photo courtesy of C. Cox

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

17

Figure 10. Securing a massasauga without a hook. Using a bucket lid

to isolate the snake so the bag can be tied safely.

Photo courtesy of C. Cox

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

18

Chapter 4. Social Environment

4.1 Group Structure and Size

Careful consideration should be given to ensure that animal group structures and sizes meet the

social, physical, and psychological well-being of those animals and facilitate species-appropriate

behaviors.

Massasaugas have been successfully housed in a variety of social configurations. Individual animals,

mixed sex, and single sex groups can be housed for long periods without apparent problems. These

snakes appear to be very tolerant of conspecifics. Rattlesnakes are often communal hibernators and

there are no known reports of injurious interactions between animals. Depending on the size of the

enclosure several snakes of mixed sexes and ages can be kept together. For example, an exhibit with 3

m

2

(32 ft

2

) floor space can accommodate up to 6 adult massasauga.

Males housed together may engage in ritualized combat. This is an innate behaviour and there are no

associated injuries. In fact, it is thought that such combat behavior may be beneficial to induce breeding

in the species.

4.2 Influence of Others and Conspecifics

Animals cared for by AZA-accredited institutions are often found residing with conspecifics, but may

also be found residing with animals of other species. Mixed exhibits should include sufficient thermal

resources (basking spots) and shelter areas to accommodate each animal individually.

Mixed species exhibits with massasauga have been attempted. Massasaugas have been

successfully housed with other snake species including bull snakes, fox snakes, hognose snakes, and

milk snakes. The potential for parasite and disease transmission should be considered. For example,

turtles can be sub-clinical carriers of Entamoeba invadens that can cause severe illness and death in

snakes. Complete parasitology and disease screening should be carried out before species are mixed.

Massasaugas do not appear to engage in any social interaction with humans. They generally view

humans as potential predators and can reactive defensively to a human caretaker. This type of reaction

varies with the individual snake. Some individuals are quite sedate and do not react while others may

react by rattling and adopting a defensive pose in which it is ready to strike out. To minimize these

behaviors, keepers should approach snakes gradually as not to surprise or startle them.

4.3 Introductions and Reintroductions

Managed care for and reproduction of animals housed in AZA-accredited institutions are dynamic

processes. Animals born in or moved between and within institutions require introduction and sometimes

reintroductions to other animals. It is important that all introductions are conducted in a manner that is

safe for all animals and humans involved.

Introducing massasauga to each other is fairly straightforward. Individuals can be introduced on

exhibit or in holding tanks. Animals can be released from a bag directing into the zoo/aquarium habitat or

can be transferred by transport box or by hooking them from a holding container directly into the new

enclosure. There is no need for gradual introductions. These snakes are not aggressive and very tolerant

towards each other. Multiple males may be kept together without problems. Males may engage in

ritualized combat, but will not harm each other.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

19

Chapter 5. Nutrition

5.1 Nutritional Requirements

A formal nutrition program is recommended to meet the

nutritional and behavioral needs of all massasauga (AZA

Accreditation Standard 2.6.2). Diets should be developed using

the recommendations of nutritionists, the Nutrition Scientific

Advisory Group (NAG) feeding guidelines

(http://www.nagonline.net/Feeding%20Guidelines/feeding_guideli

nes.htm), and veterinarians as well as AZA Taxon Advisory Groups (TAGs), and Species Survival Plan

®

(SSP) Programs. Diet formulation criteria should address the animal’s nutritional needs, feeding ecology,

as well as individual and natural histories to ensure that species-specific feeding patterns and behaviors

are stimulated.

Massasauga feed on a variety of whole vertebrate prey. Weatherhead et al. (2009) found that adult

massasaugas prey primarily on small mammals and that neonates also include snakes in their diet.

Species identified as prey of wild massasaugas include masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), meadow

jumping mouse (Zapus hudsonicus), Northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda), deer mouse

(Peromyscus maniculatus), boreal redback vole (Clethrionomys gapperi), meadow vole (Microtus

pennsylvanicus), Eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus), Northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus), red

squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), Eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger), snowshoe hare (Lepus

americanus), Eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus). Shepard et al. (2004) examined prey preference

of neonate massasauga and found they demonstrated a preference for snake prey, disinterest in anuran

and insect prey and indifference toward mammal prey. They also reported that free-ranging neonates

prey on Southern short-tailed shrews (Blarina carolinensis) which are smaller than most mammals preyed

upon by older age classes and would be easier for neonates to ingest.

It is often assumed that the nutrient profile of whole prey is complete, but it should be noted that the

nutrient composition can vary within species, life stage, and some species' nutrient composition can vary

with diet. Whole mice are most commonly used as a food item. Varying the species and life stage of prey

item offered may be beneficial. In order to add variety to the zoo diet, other food items such as birds (e.g.,

quail or chicken chicks) can be offered occasionally. Massasaugas are commonly fed every two weeks at

all life stages. Young snakes under 1 year of age can be offered food once a week if a faster growth rate

is desired to meet exhibit or breeding goals. Prey animals can be offered as freshly killed or previously

frozen. Live prey animals have been known to seriously injure snakes and are not recommended.

Steatitis, fat necrosis, and muscular degeneration have been reported as clinical and pathological signs of

vitamin E deficiency in snakes (Dierenfeld, 1989). Supplementing frozen mice with vitamin E may prevent

fat metabolism problems that can be life threatening to the snake. 10–15 IU of vitamin E can be inserted

(as a capsule or tablet) or injected (as a liquid) into the thawed mouse before feeding it to the snake. The

size of the prey item depends on the size of the snake. A prey item weighing approximately 5–10% of the

snake’s body weight should be adequate for most snakes. Prey items should be fresh or fresh-frozen,

stored appropriately and thawed in cool temperatures to ensure they present a wholesome diet with no

sign of rancidity. To prevent parasite problems, do not feed any food items originating from the wild.

Fresh, clean water should be available at all times.

5.2 Diets

The formulation, preparation, and delivery of all diets must be

of a quality and quantity suitable to meet the animal’s

psychological and behavioral needs (AZA Accreditation Standard

2.6.3). Food should be purchased from reliable, sustainable and

well-managed sources. The nutritional analysis of the food should

be regularly tested and recorded.

Individual institutions should follow their own diet acquisition,

quality, storage and preparation policies. The most common prey

species used in zoos is the laboratory mouse which was derived

from the common house mouse, Mus musculus. Occasionally bird

chicks (quail and chicken) can also be offered.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(2.6.2) A formal nutrition program is

recommended to meet the behavioral and

nutritional needs of all species and

specimens within the collection.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(2.6.3) Animal diets must be of a quality

and quantity suitable for each animal’s

nutritional and psychological needs. Diet

formulations and records of analysis of

appropriate feed items should be

maintained and may be examined by the

Visiting Committee. Animal food,

especially seafood products, should be

purchased from reliable sources that are

sustainable and/or well managed.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

20

In order to prevent accidents during feeding, offer all food items using a long handled forceps or tongs

(keeper’s hand should be a minimum of 24 inches away from the snake). Since rattlesnakes do not tend

to strike upwards, offer feed item from slightly above the snake. When multiple snakes are housed

together they should be separated for feeding by placing snakes in individual containers. If this is not

possible, snakes should be moved as far from each other as possible within the enclosure before food is

introduced. Snakes should be closely monitored while feeding and prevented from feeding on the same

prey item.

Most snakes will learn to accept dead prey. Massasaugas are pit vipers and use the heat sensitive

facial pits to aid in prey acquisition. Therefore the key is to warm the prey item and move it slightly from

side to side when presenting it directly in front of the snake. Once a massasauga senses the presence of

the warmed prey item, it will strike and envenomate the prey, releasing it immediately. After a brief pause

(30 sec–2 min) the snake will begin tongue flicking and investigating the envenomated prey and then

begin consuming it. Ingestion typically takes 2–5 min.

Snakes should be offered a thawed previously frozen mouse every second week. The food item

should be thawed in a refrigerator and can be warmed slightly (surface temperature to 35 °C [95 °F]) in

order to give it the thermal profile of a live prey item. Hold the thawed mouse under a heat lamp for

several seconds, or immerse the food item in a warm water bath.

Reluctant feeders: Some snakes are reluctant feeders and may routinely refuse diet for several weeks.

Freshly killed or live food can be used to stimulate the appetite of reluctant feeders. Once a snake is

feeding, it can be switched back to previously frozen food if desired. Reluctant feeders are often

stimulated to feed by the scent of the exposed brain of a previously frozen mouse. Make a small incision

in the head of a previously frozen mouse and expose the brain before feeding. Young massasaugas that

refuse to feed on pinkie mice will sometimes readily feed on young snakes (e.g., garter snakes and green

snakes). When using other snakes as food, the potential for disease transmission should be evaluated

and addressed. Mice can also be scented with shed skin of other snakes. If a snake is anorexic for longer

than 8 weeks, it should be evaluated by a veterinarian and supplemental nutritional support may be

required.

The sources of prey used as food items should have consistent quality control to insure that only

healthy prey items, raised on an optimal plane of nutrition, are offered. Frozen food items should be

thawed and handled properly prior to feeding. Offering wild-caught food items should not be used to

prevent introduction of potential pathogens.

Food preparation must be performed in accordance with all

relevant federal, state, or local regulations (AZA Accreditation

Standard 2.6.1). Meat processed on site must be processed

following all USDA standards. The Appropriate Hazard Analysis

and Critical Control Points (HACCP) food safety protocols for the

diet ingredients, diet preparation, and diet administration should be established for the massasauga or

species specified. Diet preparation staff should remain current on food recalls, updates, and regulations

per USDA/FDA. Remove food within a maximum of 24 hours of being offered unless state or federal

regulations specify otherwise and dispose of per USDA guidelines.

5.3 Nutritional Evaluations

Body mass index measurements may provide a guide to the condition of an animal, however, a body

mass index is currently not available for massasauga rattlesnakes. Sexually mature adults range in

weight from 180–400 g, although it may be normal for a snake to weigh over 400 g if it is a particularly

long animal (greater than 75 cm [30 in.]).

It is generally accepted that snakes fed appropriate quantities of whole prey rarely experience

nutritional problems. Monthly weighing is the best method of tracking the nutritional status of a

massasauga. Growth in reptiles continues until death (although at a slower rate later in life). A modest

(approximately 2–4%) yearly increase in mass for adult males and non-gravid females is expected.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(2.6.1) Animal food preparations must

meet all local, state/provincial, and federal

regulations.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

21

Chapter 6. Veterinary Care

6.1 Veterinary Services

Veterinary services are a vital component of excellent animal

care practices. A full-time staff veterinarian is recommended,

however, in cases where this is not practical, a consulting/part-

time veterinarian must be under contract to make at least twice

monthly inspections of the animal collection and to any

emergencies (AZA Accreditation Standard 2.1.1). Veterinary

coverage must also be available at all times so that any

indications of disease, injury, or stress may be responded to in a

timely manner (AZA Accreditation Standard 2.1.2). The AZA

Accreditation Standards recommend that AZA-accredited

institutions adopt the guidelines for medical programs developed

by the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians (AAZV) that

were updated in 2009

(

http://aazv.affiniscape.com/associations/6442/files/veterinary_sta

ndards_2009_final.docx).

AZA SSP Veterinary Advisor:

Dr. Randall E. Junge

Vice President for Animal Health, Columbus Zoo

AZA Snake TAG Veterinary Advisor:

Dr. Brad Lock

Assistant Curator of Herpetology, Zoo Atlanta

Protocols for the use and security of drugs used for veterinary

purposes must be formally written and available to animal care

staff (AZA Accreditation Standard 2.2.1). Procedures should

include, but are not limited to: a list of persons authorized to

administer animal drugs, situations in which they are to be

utilized, location of animal drugs and those persons with access

to them, and emergency procedures in the event of accidental

human exposure.

Animal recordkeeping is an important element of animal care

and ensures that information about individual animals and their

treatment is always available. A designated staff member should

be responsible for maintaining an animal record keeping system

and for conveying relevant laws and regulations to the animal

care staff (AZA Accreditation Standard 1.4.6). Recordkeeping

must be accurate and documented on a daily basis (AZA

Accreditation Standard 1.4.7). Complete and up-to-date animal

records must be retained in a fireproof container within the

institution (AZA Accreditation Standard 1.4.5) as well as be

duplicated and stored at a separate location (AZA Accreditation

Standard 1.4.4).

As a Species Survival Plan

®

(SSP) Program animal,

massasaugas must have individual records and must be

individually identifiable. Individual institutions are encouraged to

incorporate the following practices into their own record keeping protocols. All significant occurrences

(breedings, births, deaths, etc.) and yearly morphometric data should be entered into the animal’s record

and forwarded to the institutional registrar on a timely basis. The SSP Coordinator and Studbook Keeper

should be informed of any occurrences or changes that would impact population management. Further,

any novel husbandry approaches and techniques should be documented and forwarded to the Eastern

Massasauga Rattlesnake Management Committee.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(2.1.1) A full-time staff veterinarian is

recommended. However, the Commission

realizes that in some cases such is not

practical. In those cases, a

consulting/part-time veterinarian must be

under contract to make at least twice

monthly inspections of the animal

collection and respond as soon as

possible to any emergencies. The

Commission also recognizes that certain

collections, because of their size and/or

nature, may require different

considerations in veterinary care.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(2.1.2) So that indications of disease,

injury, or stress may be dealt with

promptly, veterinary coverage must be

available to the animal collection 24 hours

a day, 7 days a week.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.6) A staff member must be

designated as being responsible for the

institution's animal record-keeping

system. That person must be charged

with establishing and maintaining the

institution's animal records, as well as

with keeping all animal care staff

members apprised of relevant laws and

regulations regarding the institution's

animal collection.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.7) Animal records must be kept

current, and data must be logged daily.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.5) At least one set of the institution’s

historical animal records must be stored

and protected. Those records should

include permits, titles, declaration forms,

and other pertinent information.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.4) Animal records, whether in

electronic or paper form, including health

records, must be duplicated and stored in

a separate location.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

22

6.2 Identification Methods

Ensuring that massasaugas are identifiable through various

means increases the ability to care for individuals more

effectively. Animals must be identifiable and have corresponding

ID numbers whenever practical, or a means for accurately

maintaining animal records must be identified if individual

identifications are not practical (AZA Accreditation Standard

1.4.3).

Permanent identification is essential for following the life

history of individual animals, whether in the field or in managed

settings. Non-invasive identification methods include paint or nail

polish spots (temporary until the next skin shed or rattle

breakage. With well patterned snakes such as the massasauga,

recording the individual’s dorsal patterns of the entire body by

diagram, photo or shed skin can serve as a permanent marking

technique. The pattern of each snake is an individual “fingerprint”

and can be used to identify an individual throughout its life. A

copy of an identification photo ("mug shot") should be placed into

the individual's permanent record file for future reference.

Mildly invasive identification methods include scute clips,

rattle tags, or PIT tags (passive integrated transponder) (e.g.,

Trovan or AVID), under the skin. The key requirements of

marking techniques are that they do not affect the survival or the

performance of the marked animal (i.e., the least invasive procedure is desired) and that marks not be

lost over time. While scale-clipping and branding have been used to mark snakes (Fitch 1987), the

injection of small glass-encapsulated microchip transponders termed Passively Integrated Transponders

(PIT tags) satisfies these requirements to the greatest extent and is now standard practice.

Subcutaneous insertion involves injecting the PIT tag under the lateral scales at about the second

scale row (counting up from the ventral scutes) anterior to the cloaca on the left side. Although it is

physically easier to inject PIT tags anteriorly (because of the way the scales overlap), injecting posteriorly

(towards the tail) is recommended because of the tendency of injected bodies to migrate posteriorly. This

technique will minimize the probability of the tag being expelled through the original insertion hole.

Two people are required for this procedure. One person should carefully restrain the snake using a

restraint tube. It is important to prevent movement or flexion that can cause partial tearing of the skin at

the injection site. The second person will insert the PIT tag. The following protocol describes PIT tag

insertion in massasaugas.

1. Raise the snake’s skin at the injection site by pinching dorso-ventrally using thumb and forefinger.

2. Position the needle so that it is parallel to the long axis of the snake’s body and pointed towards

its tail.

3. Advance the needle between two scales until it has penetrated to 0.5 to 1 cm past the bevel of

the needle.

4. While holding the injector assembly steady, push the injector plunger forward, then withdraw the

needle (keeping the injector assembly stationary while the tag is injected is important because

otherwise the tag will not be inserted a sufficient distance from the injection hole).

5. If the needle did not contact the underlying musculature during the insertion or pierce one of the

skin vessels, then bleeding will likely be absent; however, if the site is bleeding apply pressure at

the injection site with a fresh Q-tip until bleeding has stopped (Note: the increased vascularization

of the skin that occurs during the approximately two-week shed cycle can substantially increase,

the occurrences of, and the amount of bleeding resulting from PIT tag insertion).

6. When the injection site is dry, apply tissue adhesive to close the opening.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.3) Animals must be identifiable,

whenever practical, and have

corresponding ID numbers. For animals

maintained in colonies or other animals

not considered readily identifiable, the

institution must provide a statement

explaining how record keeping is

maintained.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.1) An animal inventory must be

compiled at least once a year and include

data regarding acquisitions and

dispositions in the animal collection.

AZA Accreditation Standard

(1.4.2) All species owned by the

institution must be listed on the inventory,

including those animals on loan to and

from the institution. In both cases,

notations should be made on the

inventory.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) Care Manual

Association of Zoos and Aquariums

23

7. Scan the tag again to confirm functionality and to verify the tag number recorded on the snake's

record.

8. Ensure that the tissue adhesive applied to the injection site has fully dried before performing other

procedures or releasing the snake.

Scute clipping leaves an open wound subject that is to possible infection and is therefore not

recommended. For free-ranging snakes included in special field studies, a surgically implanted radio

telemetry transmitter may be appropriate. This is an invasive procedure and should only be implanted in

larger massasaugas (i.e., those weighing greater than 200 g), surgical anesthesia and sterile conditions.

Use of surgically implanted transmitters is discussed further in Chapter 10.

AZA member institutions must inventory their massasauga population at least annually and document

all massasauga acquisitions and dispositions (AZA Accreditation Standard 1.4.1). Transaction forms help

document that potential recipients or providers of the animals should adhere to the AZA Code of

Professional Ethics, the AZA Acquisition/Disposition Policy (see Appendix B), and all relevant AZA and

member policies, procedures and guidelines. In addition, transaction forms should insist on compliance

with the applicable laws and regulations of local, state, federal and international authorities. All AZA-

accredited institutions must abide by the AZA Acquisition and Disposition policy (Appendix B) and the

long-term welfare of animals should be considered in all acquisition and disposition decisions. All species

owned by an AZA institution must be listed on the inventory, including those animals on loan to and from

the institution (AZA Accreditation Standard 1.4.2).

6.3 Transfer Examination and Diagnostic Testing Recommendations

The transfer of animals between AZA-accredited institutions or certified related facilities due to AZA

Animal Program recommendations occurs often as part of a concerted effort to preserve these species.

These transfers should be done as altruistically as possible and the costs associated with specific

examination and diagnostic testing for determining the health of these animals should be considered.

Pre-shipping health screening protocols: Individual institutions should follow their own incoming and

outgoing animal testing protocols and incorporate the following specific to massasaugas. Pre-shipment

health assessment should include a complete physical examination with a whole body doro-ventral

radiograph, complete blood count (CBC), blood chemistry, fecal enteric bacterial culture, faecal

parasitological examination (direct and float). Diagnostics for Cryptosporidia should be performed [acid

fast staining of feces, indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFA) if available]. Ophidian paramyxovirus

(OPMV) testing is required by the AZA Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake SSP. Details are provided in

section 6.4.

6.4 Quarantine

AZA institutions must have holding facilities or procedures for

the quarantine of newly arrived animals and isolation facilities or

procedures for the treatment of sick/injured animals (AZA

Accreditation Standard 2.7.1). All quarantine, hospital, and

isolation areas should be in compliance with AZA