Grant Thornton

January 2022

Revenue from Contracts

with Customers

Navigating the guidance in

ASC 606 and ASC 340-40

This publication was created for general information purposes, and does not constitute professional

advice on facts and circumstances specific to any person or entity. You should not act upon the

information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation

or warranty (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained

in this publication. Grant Thornton LLP (Grant Thornton) shall not be responsible for any loss sustained

by any person or entity that relies on the information contained in this publication. This publication is not a

substitute for human judgment and analysis, and it should not be relied upon to provide specific answers.

The conclusions reached on the examples included in this publication are based on the specific facts and

circumstances outlined. Entities with slightly different facts and circumstances may reach different

conclusions, based on considering all of the available information.

The content in this publication is based on information available as of December 31, 2021. We may

update this publication for evolving views as we continue to monitor the implementation process. For the

latest version, please visit grant.thornton.com.

Portions of FASB Accounting Standards Codification

®

material included in this work are copyrighted by

the Financial Accounting Foundation, 401 Merritt 7, Norwalk, CT 06856, and are reproduced with

permission.

Contents

1. Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 6

1.1 Joint Transition Resource Group for Revenue Recognition ...................................................... 8

1.2 AICPA Revenue Recognition Task Forces ............................................................................... 9

1.3 Private Company Council .......................................................................................................... 9

2. Scope .................................................................................................................................................... 10

2.1 Sales of nonfinancial assets .................................................................................................... 11

2.2 Interaction with other guidance................................................................................................ 12

Collaborative arrangements .......................................................................................... 122

Contributions received .................................................................................................... 13

3. Identify the contract with a customer .................................................................................................... 14

3.1 Criteria for recognizing a contract............................................................................................ 14

The parties have approved the contract and are committed to perform ......................... 17

The entity can identify each party’s rights ....................................................................... 18

The entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services .............................. 19

The contract has commercial substance ........................................................................ 19

It is probable the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration......................... 19

3.2 Contracts that do not ‘pass’ Step 1 ......................................................................................... 26

Reassessing the Step 1 criteria ...................................................................................... 28

3.3 Contract term ........................................................................................................................... 30

Termination provisions .................................................................................................... 30

3.4 Portfolio practical expedient .................................................................................................... 33

3.5 Combining contracts ................................................................................................................ 35

4. Identify the performance obligations in the contract ............................................................................. 37

4.1 Identifying promises ................................................................................................................. 37

Immaterial promises ........................................................................................................ 40

Shipping and handling ..................................................................................................... 43

Preproduction activities ................................................................................................... 44

Stand-ready promises ..................................................................................................... 45

4.2 Identifying performance obligations ......................................................................................... 47

Capable of being distinct ................................................................................................. 48

Distinct within the context of the contract ........................................................................ 49

4.3 Series of distinct goods or services ......................................................................................... 57

4.4 Customer options for additional goods or services ................................................................. 62

The exercise of a material right ....................................................................................... 72

4.5 Nonrefundable upfront fees ..................................................................................................... 73

4.6 Warranties ............................................................................................................................... 78

5. Determine the transaction price ............................................................................................................ 82

5.1 Variable consideration ............................................................................................................. 83

Constraint on variable consideration ............................................................................... 90

Volume discounts ............................................................................................................ 94

Rights of return ................................................................................................................ 99

Distinguishing variable consideration from optional goods or services ........................ 102

Minimum purchase commitments ................................................................................. 104

Reassessing variable consideration.............................................................................. 106

5.2 Significant financing components .......................................................................................... 107

Adjusting for a significant financing component ............................................................ 113

Presentation .................................................................................................................. 115

5.3 Noncash consideration .......................................................................................................... 115

Contents 4

Subsequent measurement of noncash consideration ................................................... 118

5.4 Consideration payable to a customer .................................................................................... 119

5.5 Changes in the transaction price ........................................................................................... 127

5.6 Sales and other similar taxes ................................................................................................ 128

6. Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations ............................................................ 129

6.1 Determining stand-alone selling price ................................................................................... 130

Adjusted market assessment approach ........................................................................ 134

Expected cost-plus-a-margin approach ........................................................................ 135

Residual approach ........................................................................................................ 135

Using a combination of approaches .............................................................................. 137

6.2 Allocating the transaction price to the performance obligations ............................................ 138

6.2.1 Allocating based on a range of estimated stand-alone selling prices ................................... 141

6.3 Estimating the stand-alone selling price of an option ................................................................ 143

Practical alternative to estimating the stand-alone selling price of an option ............... 145

6.4 Allocating a discount .............................................................................................................. 148

6.5 Allocating variable consideration ........................................................................................... 153

Allocating variable consideration to a series ................................................................. 156

6.6 Interaction between allocating discounts and allocating variable consideration ................... 159

6.7 Changes in transaction price ................................................................................................. 159

6.8 Allocating a significant financing component ......................................................................... 162

7. Recognize revenue when or as performance obligations are satisfied .............................................. 164

7.1 Control transferred over time ................................................................................................. 166

Criteria to recognize revenue over time ........................................................................ 167

Methods to measure progress ...................................................................................... 186

Right to invoice practical expedient ............................................................................... 193

Selecting a single measure of progress ........................................................................ 196

Ability to reasonably measure progress ........................................................................ 197

Updates to measuring progress .................................................................................... 198

Pre-contract activities .................................................................................................... 198

Stand-ready obligations ................................................................................................ 199

7.2 Control transferred at a point in time ..................................................................................... 200

Customer acceptance provisions .................................................................................. 204

7.3 Trial periods ........................................................................................................................... 206

7.4 Repurchase agreements ....................................................................................................... 206

Forwards or calls ........................................................................................................... 207

Put options .................................................................................................................... 209

7.5 Bill-and-hold arrangements ................................................................................................... 211

7.6 Consignment arrangements .................................................................................................. 214

7.7 Customer’s unexercised rights .............................................................................................. 215

8. Intellectual property licenses .............................................................................................................. 217

8.1 Scope .................................................................................................................................... 217

8.2 Applying Step 2 to license arrangements .............................................................................. 219

8.3 Determining the nature of the entity’s promise in granting a license ............................ 224

8.3.1 Functional intellectual property ................................................................................... 224

8.3.2 Symbolic intellectual property ....................................................................................... 228

8.4 Transferring control of the license ......................................................................................... 234

8.4.1 Renewals ....................................................................................................................... 235

8.5 Sales-based and usage-based royalties .............................................................................. 238

8.5.1 Scope of the exception .................................................................................................. 240

8.5.2 Contracts with minimum royalty guarantees ................................................................. 242

Contents 5

9. Principal versus agent ........................................................................................................................ 246

9.1 Identifying the specified goods or services promised to the customer ................................ 248

9.2 Evaluating control .................................................................................................................. 252

9.3 Indicators of control .............................................................................................................. 254

9.4 Examples of the principal versus agent assessment ........................................................... 257

9.5 Reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses ........................................................................... 262

10. Modifications ....................................................................................................................................... 264

10.1 Identifying a modification ....................................................................................................... 264

Unpriced change orders and claims.............................................................................. 265

10.2 Accounting for the modification ............................................................................................. 267

Modifications that constitute separate contracts ........................................................... 268

Modifications that do not constitute separate contracts ................................................ 270

11. Contract costs ..................................................................................................................................... 281

11.1 Costs to obtain a contract ...................................................................................................... 282

Commissions ................................................................................................................. 286

11.2 Costs to fulfil a contract ......................................................................................................... 289

11.3 Preproduction activities ......................................................................................................... 293

Preproduction costs ...................................................................................................... 293

Determining the nature of preproduction activities ........................................................ 294

Preproduction arrangements ......................................................................................... 295

11.4 Amortization of contract costs ............................................................................................... 296

11.5 Impairment of contract costs ................................................................................................. 300

Loss contracts ............................................................................................................... 302

12. Presentation ........................................................................................................................................ 304

12.1 Contract assets and receivables ........................................................................................... 305

12.2 Contract liabilities .................................................................................................................. 307

12.3 Unit of account ....................................................................................................................... 309

12.4 Offsetting ............................................................................................................................... 310

12.5 Interaction of ASC 606 with SEC Regulation S-X, Rule 5-03(b) ........................................... 311

13. Disclosure ........................................................................................................................................... 312

13.1 Public business entities ......................................................................................................... 313

Disaggregation of revenue ............................................................................................ 314

Contract balances ......................................................................................................... 318

Performance obligations ............................................................................................... 319

Significant judgments .................................................................................................... 325

Assets recognized from costs to obtain or fulfill a contract ........................................... 326

Practical expedients for measurement under ASC 606 and ASC 340-40 .................... 327

Interim disclosure requirements .................................................................................... 327

13.2 Nonpublic entity disclosures .................................................................................................. 328

Disaggregation of revenue ............................................................................................ 328

Contract balances ......................................................................................................... 331

Performance obligations ............................................................................................... 331

Significant judgments .................................................................................................... 332

14. U.S. GAAP and IFRS comparison ...................................................................................................... 334

Appendix A: Guidance abbreviations ........................................................................................................ 340

Appendix B: Changes in this edition ........................................................................................................ 343

1. Overview

This edition of this publication has been updated to reflect technical accounting amendments issued after

December 2018 and features new illustrative examples and additional Grant Thornton insights. See

Appendix B for a summary of all changes in the 2022 edition compared to the 2018 version of this

publication.

In May 2014 the FASB and the IASB published their largely converged standards on revenue

recognition—ASU 2014-09 and IFRS 15, both titled Revenue from Contracts with Customers—which

supersede and replace virtually all existing U.S. GAAP and IFRS revenue recognition guidance, affecting

almost every revenue-generating entity.

ASC 606-10-10-1

The objective of the guidance in this Topic is to establish the principles that an entity shall apply to

report useful information to users of financial statements about the nature, amount, timing, and

uncertainty of revenue and cash flows arising from a contract with a customer.

The FASB codified the amendments in ASU 2014-09 in Topic 606, Revenue from Contracts with

Customers, which, unlike the voluminous and often industry-specific revenue recognition rules it replaced,

calls for a single, principle-based model for recognizing revenue. The core principle requires an entity to

recognize revenue in a way that depicts the transfer of goods and/or services to a customer in an amount

that reflects the consideration the entity expects to be entitled to in exchange for those goods and/or

services.

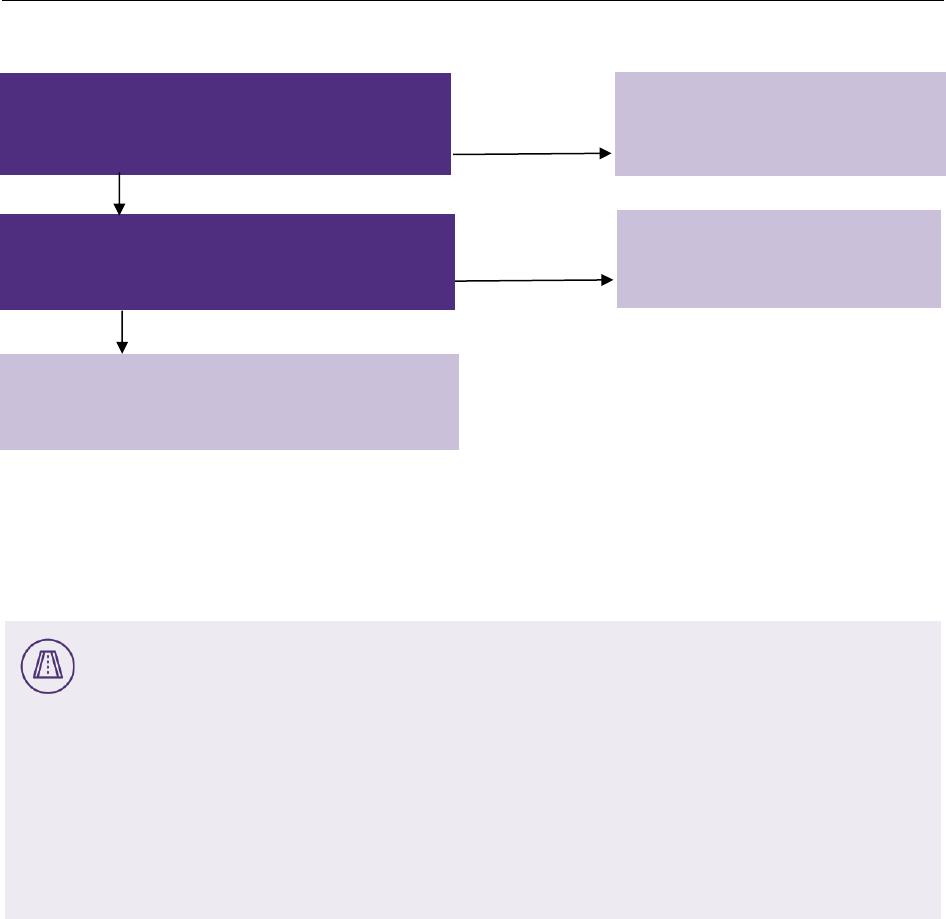

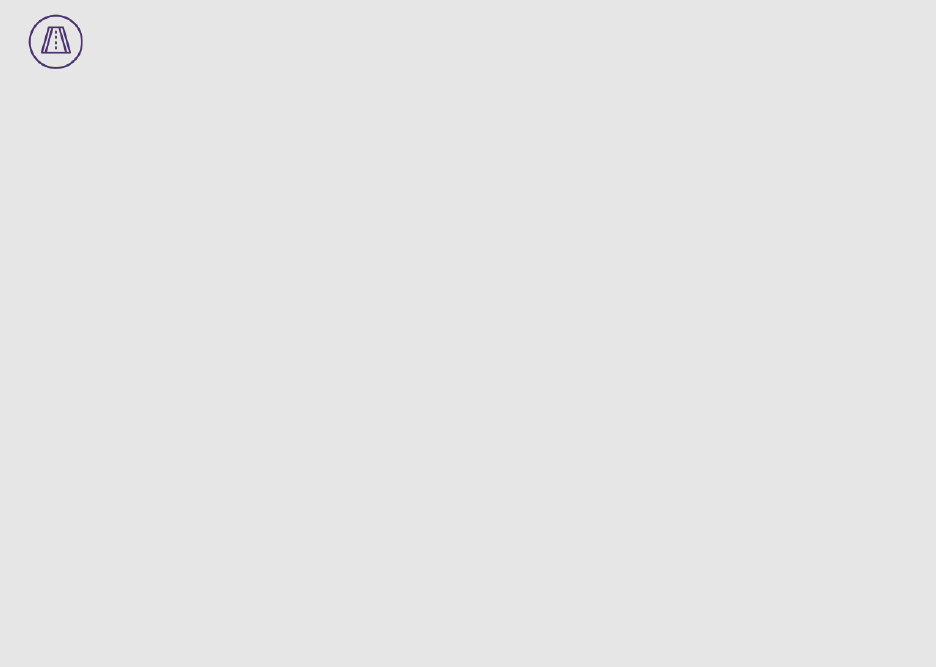

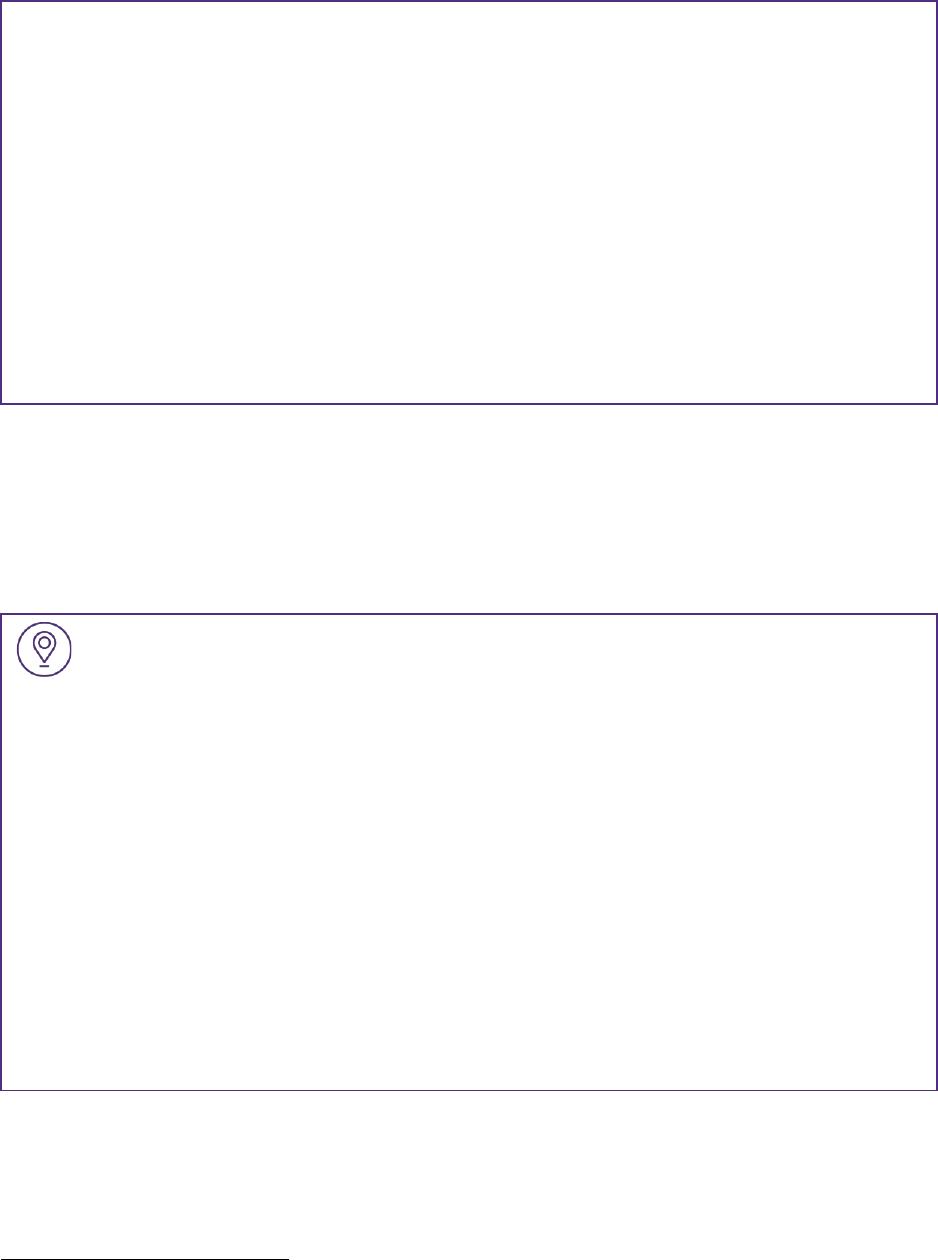

To achieve the core principle, an entity is required to apply the following five-step model:

Step 1: Identify the contract with the customer.

Step 2: Identify the performance obligations in the contract.

Step 3: Determine the transaction price.

Step 4: Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract.

Step 5: Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies its performance obligations.

Overview 7

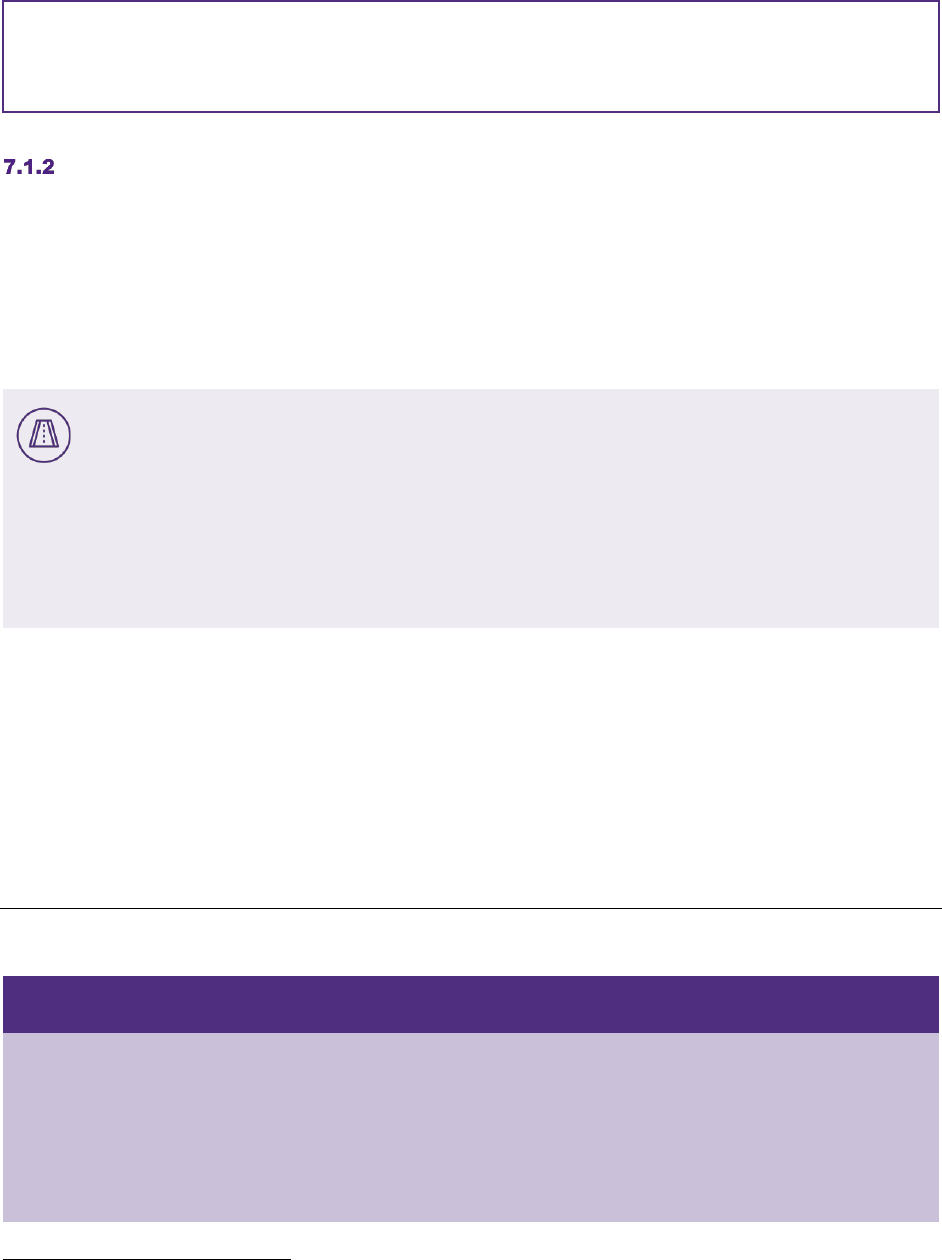

Figure 1.1: The five-step model

In addition to the five-step model, the standard provides implementation guidance on warranties,

customer options, licensing, and other topics discussed in ASC 606-10-55-3 outlined below.

ASC 606-10-55-3

This implementation guidance is organized into the following categories:

a. Assessing collectability (paragraphs 606-10-55-3A through 55-3C)

aa. Performance obligations satisfied over time (paragraphs 606-10-55-4 through 55-15)

b. Methods for measuring progress toward complete satisfaction of a performance obligation

(paragraphs 606-10-55-16 through 55-21)

c. Sale with a right of return (paragraphs 606-10-55-22 through 55-29)

d. Warranties (paragraphs 606-10-55-30 through 55-35)

e. Principal versus agent considerations (paragraphs 606-10-55-36 through 55-40)

f. Customer options for additional goods or services (paragraphs 606-10-55-41 through 55-45)

g. Customers’ unexercised rights (paragraphs 606-10-55-46 through 55-49)

h. Nonrefundable upfront fees (and some related costs) (paragraphs 606-10-55-50 through

55-53)

i. Licensing (paragraphs 606-10-55-54 through 55-60 and 606-10-55-62 through 55-65B)

j. Repurchase agreements (paragraphs 606-10-55-66 through 55-78)

k. Consignment arrangements (paragraphs 606-10-55-79 through 55-80)

l. Bill-and-hold arrangements (paragraphs 606-10-55-81 through 55-84)

m. Customer acceptance (paragraphs 606-10-55-85 through 55-88)

n. Disclosure of disaggregated revenue (paragraphs 606-10-55-89 through 55-91)

An entity recognizes revenue to depict the transfer of promised goods or services

to customers in an amount that reflects the consideration that the

entity expects to be entitled to in exchange for those goods or services.

Step 1:

Identify the

contract

Step 2:

Identify the

performance

obligations

Step 3:

Determine

the

transaction

price

Step 4:

Allocate the

transaction

price

Step 5:

Recognize

revenue

Overview 8

The remainder of this guide

• Summarizes the revenue guidance and certain FASB examples, including the amendments in

subsequent ASUs

• Incorporates discussions, insights, and examples from the Joint Transition Resource Group for

Revenue Recognition (TRG) meetings along with the applicable guidance

• Includes Grant Thornton insights on various topics

• Provides practical insights on how the guidance may differ from legacy GAAP

• Includes illustrative examples to demonstrate how to apply the guidance

At the crossroads: Principle-based model versus rules-based model

The shift in the U.S. GAAP revenue landscape from guidance that tends to be prescriptive to guidance

that is based on a single core principle requires entities to use more judgment and places an emphasis

on the underlying core principle of the guidance. Under the new guidance, an entity needs to apply

judgment, keeping in mind the underlying core principal of the guidance, to align the accounting with

the core principle.

The principle-based model requires entities to make more estimates to reflect the amount of

consideration to which an entity “expects to be entitled,” for example, when transactions have variable

consideration. In addition, the increase in estimates and judgments is accompanied by an increase in

disclosures to describe the estimation methods, inputs, and assumptions.

1.1 Joint Transition Resource Group for Revenue Recognition

Shortly after the standard was issued in 2014, the FASB and IASB formed the TRG to help entities

implement the new revenue guidance. The purpose of the group is to

• Solicit and discuss stakeholder questions arising from implementing the new revenue guidance

• Inform the Boards about implementation issues and recommend action as needed

• Provide a forum for stakeholders to learn about the new guidance

The TRG does not issue authoritative guidance, but the meeting papers (hereinafter referred to as “TRG

Paper XX, Title”) and meeting summaries provide stakeholders with additional insight as to how the new

revenue guidance should be applied, especially for those areas where TRG members reach general

agreement.

In 2016, then Deputy Chief Accountant for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Wesley

R. Bricker advised

1

SEC registrants to follow the TRG discussions, even though they are not authoritative

guidance. In other words, when an entity has a fact pattern similar to one that is included in a FASB or

IASB staff paper or discussed at a TRG meeting, the entity is advised to consult with the SEC staff if it

reaches a different conclusion on applying the guidance than the conclusion reached by the TRG.

1

Remarks before the 2016 Baruch College Financial Reporting Conference, May 5, 2016.

9 Overview

All TRG meeting papers prepared by the FASB and/or IASB staff, including examples and staff views

as well as archived meetings and meeting summaries, can be found on the TRG homepage on the

FASB website.

1.2 AICPA Revenue Recognition Task Forces

The AICPA formed 16 industry task forces to address industry-specific implementation questions and to

help develop a new accounting and auditing guide on revenue recognition. The industries involved with

this project included aerospace and defense, airlines, asset management, broker-dealers, construction

contractors, depository institutions, gaming, health care, hospitality, insurance, not-for-profit, oil and gas,

power and utility, software, telecommunications, and timeshare.

The AICPA’s Audit and Accounting Guide: Revenue Recognition contains accounting and auditing

overviews as well as industry-specific considerations for the 16 industries. While the guide contains

interpretive guidance, it does not create new GAAP and is not authoritative.

1.3 Private Company Council

The Private Company Council (PCC) is the primary advisory body to the FASB on private company

accounting issues. The PCC asked the FASB staff to prepare certain educational memos to assist with

private companies’ implementation of ASC 606. These memos, which are not authoritative, can be

found on the Implementation Q&A section of the FASB website.

2. Scope

ASC 606 applies to all contracts with customers to provide goods or services that are outputs of the

entity’s ordinary course of business in exchange for consideration, unless specifically excluded from the

scope of the new guidance, as described below.

An entity should apply the guidance in ASC 606 to all contracts with customers, except the following:

• Lease contracts within the scope of ASC 840 or ASC 842

• Contracts within the scope of ASC 944

• Guarantees (other than product or service warranties) within the scope of ASC 460

• Nonmonetary exchanges between entities in the same line of business to facilitate sales to customers

or potential customers

• Financial instruments and other contractual rights and obligations within the scope of

ASC 310, ASC 320, ASC 323, ASC 325, ASC 405, ASC 470, ASC 815, ASC 825, and ASC 860

The new revenue guidance creates Subtopic 924-815, which excludes fixed-odds wagering contracts

from the derivatives guidance. As a result, fixed-odds wagering contracts should be accounted for in

accordance with the guidance in ASC 606.

TRG area of general agreement: In or out of scope?

The TRG discussed the following types of arrangements and reached general agreement on the

applicability of the scope of ASC 606 as follows:

• Credit card fees: At its July 2015 meeting,

2

the TRG reached general agreement that credit card

fees accounted for under ASC 310 are not within the scope of ASC 606. In other words, TRG

members expect the conclusion under both legacy guidance and ASC 606 to be the same when

evaluating various revenue streams from credit card programs. An SEC observer to the meeting

cautioned, however, that entities should not assume that any fee connected to a credit card or any

arrangement labeled as a credit card lending arrangement would automatically fall within the scope

of ASC 310. In other words, the entity must assess whether the nature of the overall arrangement

is a credit card lending arrangement and, if not, the entity should not presume that the

arrangement is entirely within the scope of ASC 310.

2

TRG Paper 36, Scope: Credit Cards.

A customer is a party that has contracted with an entity to obtain goods or services that are an output

of the entity’s ordinary activities in exchange for consideration.

Scope 11

• Credit card reward programs: At its July 2015 meeting,

3

the TRG also generally agreed that an

entity must apply judgment and consider all facts and circumstances of the specific credit

cardholder award program in question to determine whether the reward program is within the

scope of ASC 606. If an entity determines that all fees related to the program, including the credit

card fees, are within the scope of ASC 310, the program would not be within the scope of

ASC 606.

• Servicing and sub-servicing fees: At its April 2016 meeting,

4

the TRG generally agreed that

servicing and sub-servicing fees are in the scope of ASC 860 and therefore are excluded from the

scope of ASC 606.

• Deposit-related fees: At its April 2016 meeting,

5

the TRG generally agreed that deposit-related

fees are within the scope of ASC 606. While the deposit-related liability is within the scope of

ASC 405 and is excluded from the scope of ASC 606, ASC 405 lacks accounting guidance for

deposit-related fees. Therefore, it is appropriate to apply the guidance in ASC 606 to deposit-

related fees.

• Carried interest: At its April 2016 meeting,

6

the TRG members generally agreed that incentive-

based performance fees in the form of an allocation of capital from an investment fund under

management, referred to as a “carried interest,” are within the scope of ASC 606. Some TRG

members indicated that a reasonable alternative view could be that the carried interest is an equity

arrangement, because it is, in form, an interest in the entity. Some TRG members noted this

alternative view may lead to questions regarding whether an asset manager should consolidate the

fund. The SEC staff observer stated that the SEC staff would most likely accept the application of

ASC 606 to carried interest arrangements but also noted that there could be a basis for following

an ownership model. The SEC staff would expect entities that apply an ownership model to include

an analysis of the consolidation model under ASC 810, Consolidation, the equity method of

accounting under ASC 323, Investments – Equity Method and Joint Ventures, or other relevant

guidance.

• Preproduction activities: At its November 2015 meeting,

7

the TRG discussed whether certain

pre-production costs fall within the scope of ASC 340-10 or ASC 340-40. See additional discussion

at Section 11.3.

2.1 Sales of nonfinancial assets

The new revenue guidance adds ASC 610-20 to provide guidance on accounting for sales of nonfinancial

assets and, therefore, amends ASC 360 and ASC 350. ASC 610-20 requires entities to apply the

guidance in ASC 606 on contract existence, control, and measurement to transfers of nonfinancial assets

that are not an output of the entity’s ordinary activities.

3

Ibid

4

TRG Paper 52, Scoping Considerations for Financial Institutions.

5

Ibid.

6

TRG Paper 50, Scoping Considerations for Incentive-based Capital Allocations, Such as Carried

Interest.

7

TRG Paper 46, Pre-production costs.

Scope 12

Sales of nonfinancial assets

Quality Paper (QP) is a manufacturer of paper goods that operates in seven locations across the United

States. QP builds a new facility in Omaha and sells its existing facility in Lincoln to a third party. The

sale of manufacturing facilities is not an output of QP’s ordinary activities; however, QP should still apply

the contract existence, control, and measurement provisions in ASC 606 to the sale of its Lincoln facility.

Applying those provisions, however, will not affect QP’s income statement presentation of any resulting

gain or loss from the facility sale.

2.2 Interaction with other guidance

A contract with a customer may be partially within the scope of ASC 606 and partially within the scope of

other ASC Topics. If the other Topics specify how to separate and/or measure a portion of the contract,

then that guidance should be applied first. The amounts measured under other Topics should be

excluded from the transaction price that is allocated to performance obligations under ASC 606. If the

other Topics do not stipulate how to separate and/or measure a portion of the contract, then ASC 606

should be used to separate and/or measure that portion of the contract.

ASC 606-10-15-4

A contract with a customer may be partially within the scope of this Topic and partially within the scope

of other Topics listed in paragraph 606-10-15-2.

a. If the other Topics specify how to separate and/or initially measure one or more parts of the

contract, then an entity shall first apply the separation and/or measurement guidance in those

Topics. An entity shall exclude from the transaction price the amount of the part (or parts) of the

contract that are initially measured in accordance with other Topics and shall apply paragraphs

606-10-32-28 through 32-41 to allocate the amount of the transaction price that remains (if any) to

each performance obligation within the scope of this Topic and to any other parts of the contract

identified by paragraph 606-10-15-4(b).

b. If the other Topics do not specify how to separate and/or initially measure one or more parts of the

contract, then the entity shall apply the guidance in this Topic to separate and/or initially measure

the part (or parts) of the contract.

2.2.1 Collaborative arrangements

A collaborative arrangement is defined as a contractual arrangement under which two or more parties

actively participate in a joint operating activity and are exposed to significant risks and rewards that

depend on the activity’s commercial success. Therefore, an entity that enters into arrangements such as

those for collaborative research and development activities will need to evaluate the particular facts and

circumstances of each contract to determine if the collaborative arrangement participant is a customer.

The FASB issued ASU 2018-18 to clarify the interaction between the guidance for certain collaborative

arrangements in ASC 808 and ASC 606. In particular, the amendments in the ASU clarify that certain

transactions between collaborative arrangement participants should be accounted for as revenue under

ASC 606 if the collaborative arrangement participant is a customer with respect to the “unit of account”

(identified as a promised good or service, or a bundle of goods or services, that is distinct within the

Scope 13

collaborative arrangement under the related guidance in ASC 606). An entity that accounts for this type of

transaction under ASC 606 should apply all of the guidance in ASC 606, including the recognition,

measurement, presentation, and disclosure requirements. Also, a transaction with a collaborative

arrangement participant that is not directly related to sales to third parties should not be presented

together with revenue recognized under ASC 606 if the collaborative arrangement participant is not a

customer.

The amendments in ASU 2018-18 are effective for public business entities in fiscal years, and in interim

periods within those fiscal years, beginning after December 15, 2019. All other entities have an additional

year. Early adoption is permitted; however, entities may not adopt the amendments prior to adopting

ASC 606.

2.2.2 Contributions received

The FASB issued ASU 2018-08 to address concerns about the diversity in accounting for grants and

contracts for not-for-profit (NFP) entities.

The amendments provide a framework for determining whether a particular transaction is an exchange

transaction, contribution transaction, or other type of transaction, such as an agency transaction, and

whether a contribution is conditional or unconditional. Exchange transactions are a form of reciprocal

transaction, which means that both parties give and receive something that has economic value. In

contrast, contributions are a form of nonreciprocal transaction, meaning that the resource provider neither

expects to receive, nor receives, economic value in return for its donation.

Exchange transactions are excluded from the scope of ASC 958-605 and instead are accounted for under

other guidance, including ASC 606.

For additional information, refer to Grant Thornton’s New Developments Summary 2018-06, “FASB

clarifies scope of contribution accounting: Impact on both recipients and resource providers.”

3. Identify the contract with a customer

Because the guidance in ASC 606 applies only to contracts with customers, the first step in the model is

to identify those contracts.

ASC 606-10-25-2

A contract is an agreement between two or more parties that creates enforceable rights and

obligations. Enforceability of the rights and obligations in a contract is a matter of law. Contracts can be

written, oral, or implied by an entity’s customary business practices. The practices and processes for

establishing contracts with customers vary across legal jurisdictions, industries, and entities. In

addition, they may vary within an entity (for example, they may depend on the class of customer or the

nature of the promised goods or services). An entity shall consider those practices and processes in

determining whether and when an agreement with a customer creates enforceable rights and

obligations.

The guidance in ASC 606-10-25-2 makes it clear that the rights and obligations in a contract must be

“enforceable” before an entity applies the five-step revenue model. Enforceability is a matter of law, so an

entity needs to consider the local relevant legal environment to determine whether rights and obligations

are enforceable. That said, while the contract must be legally enforceable, oral or implied promises may

give rise to performance obligations in the contract under Step 2 (Section 4).

To assist entities in determining if an arrangement is within the scope of ASC 606, the guidance specifies

five criteria that the arrangement must meet.

3.1 Criteria for recognizing a contract

Step 1 serves as a “gate” through which a contract must pass before an entity applies the later steps of

the model to that contract. In other words, if at the inception of an arrangement, an entity concludes that

the criteria below are not met, it should not apply Steps 2 through 5 of the model until it determines that

the Step 1 criteria are subsequently met. Significant judgment may be required to conclude whether an

accounting contract exists. When a contract meets the five criteria and “passes” Step 1, the entity will not

reassess the Step 1 criteria unless there is an indication of a significant change in facts and

circumstances (Section 3.2.1).

A contract is an agreement between two or more parties that creates enforceable rights

and obligations.

A customer is a party that has contracted with an entity to obtain goods or services that are an output

of the entity’s ordinary activities in exchange for consideration.

Identify the contract with a customer 15

An accounting contract exists only when an arrangement with a customer meets the following five criteria:

• The parties have approved the contract and are committed to perform their contractual obligations.

• The entity can identify each party’s rights.

• The entity can identify the payment terms.

• The contract has commercial substance.

• It is probable that the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration to which it expects to be

entitled.

If the arrangement does not meet the five criteria, an accounting contract does not exist, even though a

legal contract may exist, and the entity follows the guidance in ASC 606-10-25-7 as described in

Section 3.2.

ASC 606-10-25-1

An entity shall account for a contract with a customer that is within the scope of this Topic only when all

of the following criteria are met:

a. The parties to the contract have approved the contract (in writing, orally, or in accordance with

other customary business practices) and are committed to perform their respective obligations.

b. The entity can identify each party’s rights regarding the goods or services to be transferred.

c. The entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services to be transferred.

d. The contract has commercial substance (that is, the risk, timing, or amount of the entity’s future

cash flows is expected to change as a result of the contract).

e. It is probable that the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration to which it will be

entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer (see

paragraphs 606-10-55-3A through 55-3C). In evaluating whether collectibility of an amount of

consideration is probable, an entity shall consider only the customer’s ability and intention to pay

that amount of consideration when it is due. The amount of consideration to which the entity will be

entitled may be less than the price stated in the contract if the consideration is variable because the

entity may offer the customer a price concession (see paragraph 606-10-32-7).

Identify the contract with a customer 16

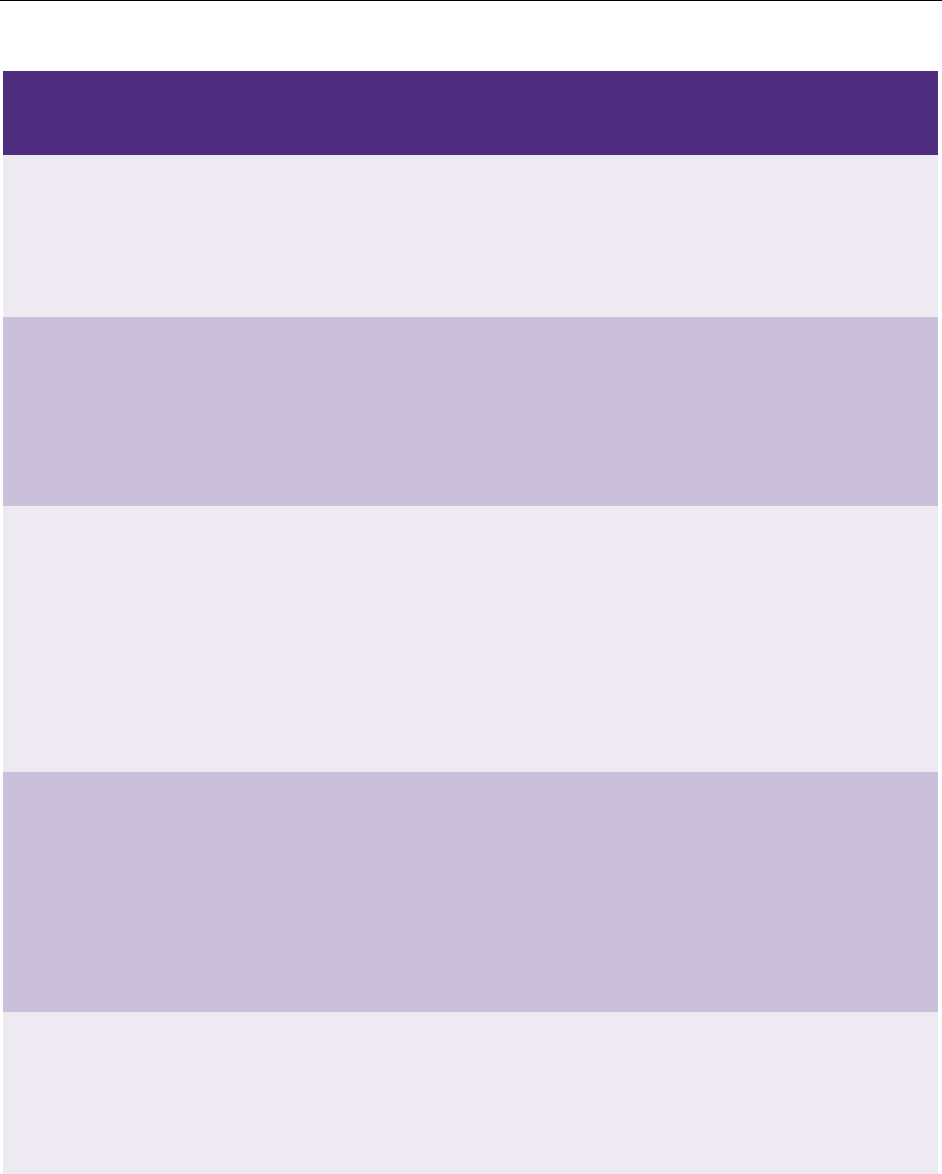

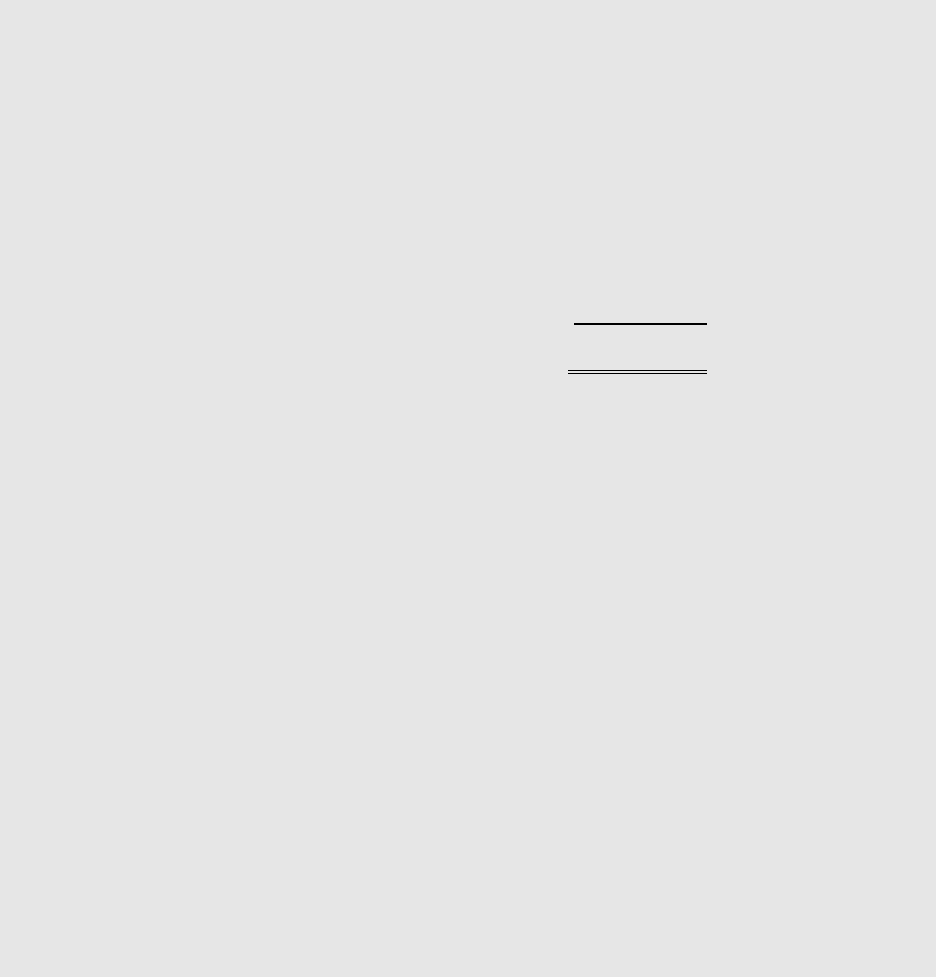

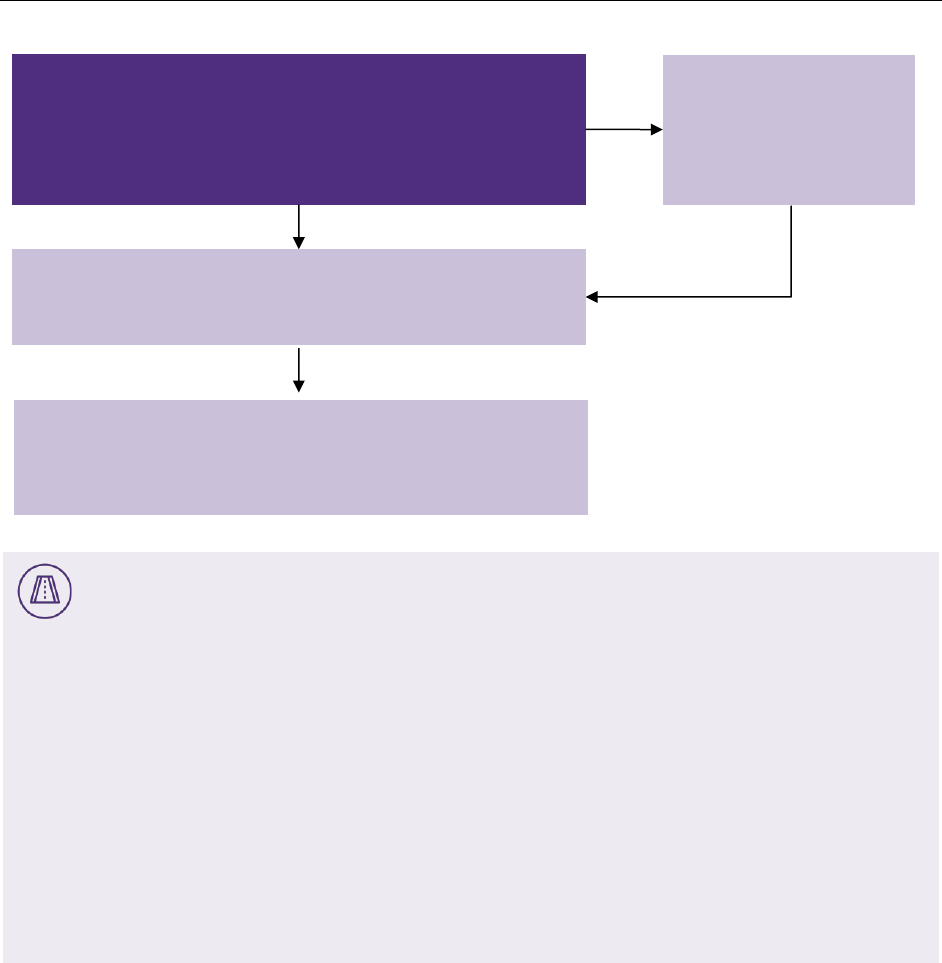

Figure 3.1: Criteria for recognizing a contract

Grant Thornton insight: New guidance may impact existing processes and controls

ASC 606 includes new criteria that must be met before an entity can recognize revenue from a

customer contract. An entity’s business processes and controls might change as a result of

implementing the new guidance. Controls that were designed in response to the revenue recognition

criteria in the legacy revenue guidance may no longer apply. In addition, new controls might be

Can the entity identify each party’s rights regarding the

goods/services to be transferred? (Section 3.1.2)

Consider if the contract meets each of the five criteria

to pass Step 1:

Have the parties approved the contract?

(Section 3.1.1)

Can the entity identify the payment terms for the

goods/services to be transferred? (Section 3.1.3)

Does the contract have commercial substance?

(Section 3.1.4)

Is it probable that the entity will collect substantially all

of the consideration to which it will be entitled in

exchange for the goods/services that will be transferred

to the customer? (Section 3.1.5)

Proceed to Step 2 and only reassess the Step 1 criteria

if there is an indication of a significant change in facts

and circumstances. (Section 3.2.1)

Y

Y

Y

Y

Y

N

Recognize consideration received

as a liability until each of the five

criteria in Step 1 are met or the

consideration received is

nonrefundable and one of the

following occurs:

1. The entity’s performance is

complete and substantially all of

the consideration has been

collected.

2. The contract has been

terminated.

3. The entity has transferred

control of the goods/services to

which the consideration

received relates, has stopped

transferring goods/services to

the customer, and has no

obligation to transfer additional

goods/services. (Section 3.2)

N

N

N

N

Continue to assess the contract to

determine if the Step 1 criteria are

met.

Identify the contract with a customer 17

needed, or existing controls might need to be modified, to ensure that an entity’s controls are

effectively designed to address the accounting criteria in ASC 606.

In our experience, many entities’ existing control environments include contract review controls, such

as a contract review template or checklist. The criteria evaluated in these or other review activities will

likely change as entities implement the new revenue standard. For example, if an entity is likely to

grant a customer a price concession, revenue may be recognized earlier under ASC 606 than under

the legacy guidance, since the requirement that the amount of consideration must be fixed or

determinable no longer applies. As a result, the adoption of ASC 606 may cause an entity that is likely

to grant a customer a price concession to evaluate earlier in the contract lifecycle whether revenue

may be recognized and may also result in additional policies, procedures, and controls to account for a

concession as variable consideration, whereas previously the entity may have waited until the contract

price was fixed or determinable to recognize revenue under ASC 605.

Further, the new standard is principles-based and will require management to use judgment in many

areas. As a result, entities should carefully evaluate where additional training, new policies or

procedures, or control activities are needed to ensure that controls are effectively designed.

The parties have approved the contract and are committed to perform

To pass Step 1, the parties must approve the contract. This approval may be written, oral, or implied, as

long as the parties intend to be bound by the terms and conditions of the contract.

The parties should also be committed to performing their respective obligations under the contract. This

does not mean that the parties need to be committed to fulfill all of their respective rights and obligations

in order for this criterion to be met. For example, an entity may include a requirement in a contract for the

customer to purchase a minimum quantity of goods each month, but the entity may have a history of not

enforcing the requirement. In this example, the contract approval criterion can still be satisfied if evidence

supports that the customer and the entity are both substantially committed to the contract. The FASB and

IASB noted

8

that requiring all of the rights and obligations to be fulfilled would have inappropriately

resulted in no recognition of revenue for some contracts in which the parties are substantially committed

to the contract.

At the crossroads: Persuasive evidence of an arrangement under SAB Topic 13 versus

ASC 606 criteria

In accordance with SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) Topic 13, revenue is generally earned and

realized (or realizable) when all of the following criteria are met:

• Persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists.

• Delivery has occurred or services have been rendered.

• The seller’s price to the buyer is fixed or determinable.

• Collectibility is reasonably assured.

8

BC36, ASU 2014-09.

Identify the contract with a customer 18

The requirement under legacy GAAP that “persuasive evidence of an arrangement exists” is essentially

being replaced by several criteria in ASC 606-10-25-1, including the requirements that the parties have

approved the contract and are committed to perform, the entity can identify each party’s rights

regarding the goods or services to be transferred, and the entity can identify the payment terms for the

goods or services to be transferred.

“Persuasive evidence” under SAB Topic 13 was dictated by an entity’s customary business practices,

which may vary among entities. This requirement is similar to the criterion in ASC 606 that the parties

have approved the contract and are committed to perform. In addition, an entity’s customary practices

may vary by the type of customer or by the nature of the product delivered or services rendered.

Like under SAB Topic 13, an entity applying ASC 606 should carefully consider the existence of side

agreements. A side agreement may call into question whether the original agreement is final and

contains all rights and obligations of the parties.

Some entities offer free trial periods to prospective customers to entice business. These trial periods must

be carefully evaluated to determine if evidence exists to support that the customer has approved the

contract and is committed to perform.

Evaluating trial periods

Members of a wine club receive a bottle of wine each month for 12 months for $20 per month. The wine

vendor is offering a promotional trial period to prospective customers starting January 1, 2018. Under

the terms of the promotion, the vendor offers new participants up to a free two-month trial period. If

participants wish to join the club, they must notify the vendor any time before the trial period lapses

(February 28, 2018). Participants that join the club receive an invoice for the 12-month membership

period, which will end February 28, 2019.

Until the customer gives notice to the wine vendor of its acceptance of the offer (either orally or written),

the entity might not conclude that the customer has approved the contract and is committed to perform.

The entity can identify each party’s rights

An entity must be able to identify its rights, as well as the rights of all other parties to the contract. An

entity cannot assess the transfer of goods or services if it cannot identify each party’s rights regarding

those goods or services.

An entity may utilize a master service arrangement or master supply arrangement (MSA) with its

customers. Each MSA must be evaluated to determine if the MSA alone establishes enforceable rights

and obligations.

The MSA may establish only basic terms and conditions with customers and the entity may require its

customers to also submit purchase orders specifying quantify and/or type of goods or services. In such

cases, the MSA alone may not establish enforceable rights and obligations of the parties. Assuming all of

the other criteria in ASC 606-10-25-1 are met, the MSA might not pass Step 1, and a contract might not

exist, until a purchase order is submitted and approved. Often this will lead to each purchase order being

a contract, depending on facts and circumstances.

Identify the contract with a customer 19

An MSA that specifies minimum purchase quantities may create enforceable rights and obligations;

however, if the entity has a past practice of waiving the minimum purchase requirement and such practice

would render the term legally unenforceable, then the term is not considered when determining if the

MSA alone creates legally enforceable rights and obligations.

The entity can identify the payment terms for the goods or services

An entity must also be able to identify the payment terms for the promised goods or services within the

contract. The entity cannot determine how much it will receive in exchange for the promised goods or

services (the “transaction price” in Step 3 of the model) if it cannot identify the contractual payment terms.

At the crossroads: Fixed or determinable under SAB Topic 13

Unlike the SAB Topic 13 requirement that the payment be “fixed or determinable,” under ASC 606, the

payment need not be fixed; however, the contract must include enough information for the entity to

estimate the amount of consideration that it expects to be entitled to.

The contract has commercial substance

A contract has commercial substance if the risk, timing, or amount of the entity’s cash flows is expected to

change as a result of the contract. In other words, the contract must have economic consequences. This

criterion was added to prevent entities from transferring goods or services back and forth to each other for

little or no consideration to artificially inflate their revenue. This criterion is applicable for both monetary

and nonmonetary transactions, because without commercial substance, it is questionable whether an

entity has entered into a transaction that has economic consequences.

It is probable the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration

To pass Step 1, an entity must determine that it is probable that it will collect substantially all of the

consideration to which it will be entitled under the contract in exchange for goods or services that it will

transfer to the customer. This criterion is also referred to as the “collectibility assessment.” In determining

whether collection is probable, the entity considers the customer’s ability and intention to pay when

amounts are due.

The objective of the collectibility assessment is to evaluate whether there is a substantive transaction

between the entity and the customer. When evaluating collectibility, an entity bases its assessment on

whether the customer has the ability and intention to pay the promised consideration in exchange for the

goods or services that will be transferred under the contract, rather than assessing the collectibility of the

consideration promised for all of the promised goods or services.

Probable: The future event or events are likely to occur.

Identify the contract with a customer 20

ASC 606-10-55-3A

Paragraph 606-10-25-1(e) requires an entity to assess whether it is probable that the entity will collect

substantially all of the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services

that will be transferred to the customer. The assessment, which is part of identifying whether there is a

contract with a customer, is based on whether the customer has the ability and intention to pay the

consideration to which the entity will be entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be

transferred to the customer. The objective of this assessment is to evaluate whether there is a

substantive transaction between the entity and the customer, which is a necessary condition for the

contract to be accounted for under the revenue model in this Topic.

ASC 606-10-55-3B

The collectibility assessment in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e) is partly a forward-looking assessment. It

requires an entity to use judgment and consider all of the facts and circumstances, including the

entity’s customary business practices and its knowledge of the customer, in determining whether it is

probable that the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration to which it will be entitled in

exchange for the goods or services that the entity expects to transfer to the customer. The assessment

is not necessarily based on the customer’s ability and intention to pay the entire amount of promised

consideration for the entire duration of the contract.

An entity should determine whether the contractual terms and its customary business practices indicate

that it has the ability and intent to mitigate credit risk. For example, some contracts may require upfront

payments before any goods or services are transferred to the customer. Any consideration received

before the entity transfers the goods or services would not be subject to credit risk. In other cases, such

as a telecom providing wireless network access to a building, the entity may be able to stop transferring

goods or services under the contract upon a customer’s failure to pay. In that situation, the entity would

consider the likelihood of payment for only the promised goods or services that will be transferred to the

customer.

An entity is precluded from considering its ability to repossess an asset transferred to a customer when

assessing collectibility.

ASC 606-10-55-3C

When assessing whether a contract meets the criterion in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e), an entity should

determine whether the contractual terms and its customary business practices indicate that the entity’s

exposure to credit risk is less than the entire consideration promised in the contract because the entity

has the ability to mitigate its credit risk. Examples of contractual terms or customary business practices

that might mitigate the entity’s credit risk include the following:

a. Payment terms—In some contracts, payment terms limit an entity’s exposure to credit risk. For

example, a customer may be required to pay a portion of the consideration promised in the

contract before the entity transfers promised goods or services to the customer. In those cases,

any consideration that will be received before the entity transfers promised goods or services to the

customer would not be subject to credit risk.

b. The ability to stop transferring promised goods or services—An entity may limit its exposure to

credit risk if it has the right to stop transferring additional goods or services to a customer in the

Identify the contract with a customer 21

event that the customer fails to pay consideration when it is due. In those cases, an entity should

assess only the collectibility of the consideration to which it will be entitled in exchange for the

goods or services that will be transferred to the customer on the basis of the entity’s rights and

customary business practices. Therefore, if the customer fails to perform as promised and,

consequently, the entity would respond to the customer’s failure to perform by not transferring

additional goods or services to the customer, the entity would not consider the likelihood of

payment for the promised goods or services that will not be transferred under the contract.

An entity’s ability to repossess an asset transferred to a customer should not be considered for the

purpose of assessing the entity’s ability to mitigate its exposure to credit risk.

The following examples from ASC 606 illustrate the guidance on assessing credit risk and the collectibility

criterion.

Example 1—Collectibility of the Consideration; Case B—Credit Risk is Mitigated

ASC 606-10-55-98A

An entity, a service provider, enters into a three-year service contract with a new customer of low credit

quality at the beginning of a calendar month.

ASC 606-10-55-98B

The transaction price of the contract is $720, and $20 is due at the end of each month. The standalone

selling price of the monthly service is $20. Both parties are subject to termination penalties if the

contract is cancelled.

ASC 606-10-55-98C

The entity’s history with this class of customer indicates that while the entity cannot conclude it is

probable the customer will pay the transaction price of $720, the customer is expected to make the

payments required under the contract for at least 9 months. If, during the contract term, the customer

stops making the required payments, the entity’s customary business practice is to limit its credit risk by

not transferring further services to the customer and to pursue collection for the unpaid services.

ASC 606-10-55-98D

In assessing whether the contract meets the criteria in paragraph 606-10-25-1, the entity assesses

whether it is probable that the entity will collect substantially all of the consideration to which it will be

entitled in exchange for the service that will be transferred to the customer. This includes assessing the

entity’s history with this class of customer in accordance with paragraph 606-10-55-3B and its business

practice of stopping service in response to customer nonpayment in accordance with paragraph 606-

10-55-3C. Consequently, as a part of this analysis, the entity does not consider the likelihood of

payment for services that would not be provided in the event of the customer’s nonpayment because

the entity is not exposed to credit risk for those services.

ASC 606-10-55-98E

It is not probable that the entity will collect the entire transaction price ($720) because of the customer’s

low credit rating. However, the entity’s exposure to credit risk is mitigated because the entity has the

ability and intention (as evidenced by its customary business practice) to stop providing services if the

Identify the contract with a customer 22

customer does not pay the promised consideration for services provided when it is due. Therefore, the

entity concludes that the contract meets the criterion in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e) because it is

probable that the customer will pay substantially all of the consideration to which the entity is entitled

for the services the entity will transfer to the customer (that is, for the services the entity will provide for

as long as the customer continues to pay for the services provided). Consequently, assuming the

criteria in paragraph 606-10-25-1(a) through (d) are met, the entity would apply the remaining guidance

in this Topic to recognize revenue and only reassess the criteria in paragraph 606-10-25-1 if there is an

indication of a significant change in facts or circumstances such as the customer not making its

required payments.

Example 1—Collectibility of the Consideration; Case C—Credit Risk is Not Mitigated

ASC 606-10-55-98F

The same facts as in Case B apply to Case C, except that the entity’s history with this class of

customer indicates that there is a risk that the customer will not pay substantially all of the

consideration for services received from the entity, including the risk that the entity will never receive

any payment for any services provided.

ASC 606-10-55-98G

In assessing whether the contract with the customer meets the criteria in 606-10-25-1, the entity

assesses whether it is probable that it will collect substantially all of the consideration to which it will be

entitled in exchange for the goods or services that will be transferred to the customer. This includes

assessing the entity’s history with this class of customer and its business practice of stopping service in

response to the customer’s nonpayment in accordance with paragraph 606-10-55-3C.

ASC 606-10-55-98H

At contract inception, the entity concludes that the criterion in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e) is not met

because it is not probable that the customer will pay substantially all of the consideration to which the

entity will be entitled under the contract for the services that will be transferred to the customer. The

entity concludes that not only is there a risk that the customer will not pay for services received from

the entity, but also there is a risk that the entity will never receive any payment for any services

provided. Subsequently, when the customer initially pays for one month of service, the entity accounts

for the consideration received in accordance with 606-10-25-7 through 25-8. The entity concludes that

none of the events in paragraph 606-10-25-7 have occurred because the contract has not been

terminated, the entity has not received substantially all of the consideration promised in the contract,

and the entity is continuing to provide services to the customer.

ASC 606-10-55-98I

Assume that the customer has made timely payments for several months. In accordance with

paragraph 606-10-25-6, the entity assesses the contract to determine whether the criteria in paragraph

606-10-25-1 are subsequently met. In making that evaluation, the entity considers, among other things,

its experience with this specific customer. On the basis of the customer’s performance under the

contract, the entity concludes that the criteria in 606-10-25-1 have been met, including the collectibility

criterion in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e). Once the criteria in paragraph 606-10-25-1 are met, the entity

applies the remaining guidance in this Topic to recognize revenue.

Identify the contract with a customer 23

At the crossroads: How does the collectibility assessment differ under SAB Topic 13

versus ASC 606?

The new guidance regarding collectibility is somewhat similar to that under SAB Topic 13, which states

that collectibility must be “reasonably assured” before revenue is recognized. However, under SAB

Topic 13, an entity evaluates collectibility when revenue is recognized, while under ASC 606, an entity

evaluates collectibility in Step 1 when it determines whether an accounting contract exists.

Another significant difference is that SAB Topic 13 requires that the entire contract price be reasonably

assured before an entity can recognize revenue, while under ASC 606, an entity does not apply the

concept of collectibility to the portion of the contract for which the entity will not transfer goods or

services (for example, in the event that the customer stops paying).

ASC 606 specifies a sequence and an entity must conclude in Step 1 that collectibility is probable

before proceeding to Step 2 (or Steps 3 through 5).

Another difference from SAB Topic 13 is that ASC 606 explicitly requires an entity to consider whether

the transaction price is variable (see Section 5.1) because the entity may offer the customer a price

concession before determining that collectibility is probable.

Portfolio considerations when assessing collectibility

The TRG has discussed stakeholder questions that have arisen with respect to assessing collectibility

when an entity elects to account for its contracts on a portfolio basis, as described in Section 3.4.

TRG area of general agreement: How should an entity assess collectibility for

a portfolio of contracts?

At its January 2015 meeting,

9

the TRG discussed how an entity should assess collectibility at contract

inception when the entity has historical experience that indicates it will not collect consideration from

some customers in a portfolio of contracts.

For example, ABC Corp. has a large number of similar customer contracts for which it bills on a

monthly basis in arrears. ABC Corp. performs credit assessment procedures before accepting a

customer. When these procedures result in the conclusion that it is not probable the customer will pay

the amounts owed, the entity does not accept the customer. Because these procedures are only

designed to determine whether collection is probable (and thus not a certainty), the entity anticipates

that it will have some customers that will not pay all amounts owed. Historical evidence, which is

representative of its expectations for the future, indicates that the entity will only collect 98 percent of

the amounts billed.

TRG members agreed that if an entity considers collectibility of the transaction price to be probable for

a portfolio of contracts, then the entity should recognize revenue in full and perform a separate

evaluation of the receivable for impairment. For example, if an entity bills $100 to its customers in a

particular month and expects bad debt expense of $2, the entity should recognize revenue of $100 and

9

TRG Paper 13, Collectibility.

Identify the contract with a customer 24

a corresponding receivable representing its right to consideration that is unconditional when the entity

satisfies its performance obligations. The guidance does not support the view that only $98 of revenue

should be recognized in this example, because the entity evaluated collectibility for each customer and

concluded that it is probable that each customer will pay the amount to which the entity will be entitled

for a total of $100.

The resultant contract asset or receivable should be assessed for impairment under the receivable

guidance in ASC 310. An entity would recognize the difference between the measurement of the

receivable and the corresponding revenue as bad debt expense.

Price concessions

In determining the “consideration to which an entity will be entitled” for purposes of the collectibility

assessment, an entity needs to evaluate at contract inception whether it expects to provide a price

concession that will result in receiving less than the full contract price from the customer. Although price

concessions are a form of variable consideration and are more fully evaluated when determining the

transaction price under Step 3 (Section 5.1), when evaluating collectibility under Step 1, an entity should

also assess at the onset of an arrangement whether it expects to provide a price concession.

When an entity expects to accept less than the contractual amount for goods and services that will be

transferred to the customer, it should evaluate all relevant facts and circumstances, which may require

significant judgment, to determine whether it has accepted a customer’s credit risk or has provided an

implicit price concession.

Example 2—Consideration is Not the Stated Price—Implicit Price Concession

ASC 606-10-55-99

An entity sells 1,000 units of a prescription drug to a customer for promised consideration of $1 million.

This is the entity’s first sale to a customer in a new region, which is experiencing significant economic

difficulty. Thus, the entity expects that it will not be able to collect from the customer the full amount of

the promised consideration. Despite the possibility of not collecting the full amount, the entity expects

the region’s economy to recover over the next two to three years and determines that a relationship

with the customer could help it to forge relationships with other potential customers in the region.

ASC 606-10-55-100

When assessing whether the criterion in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e) is met, the entity also considers

paragraph 606-10-32-2 and 606-10-32-7(b). Based on the assessment of the facts and circumstances,

the entity determines that it expects to provide a price concession and accept a lower amount of

consideration from the customer. Accordingly, the entity concludes that the transaction price is not

$1 million and, therefore, the promised consideration is variable. The entity estimates the variable

consideration and determines that it expects to be entitled to $400,000.

ASC 606-10-55-101

The entity considers the customer’s ability and intention to pay the consideration and concludes that

even though the region is experiencing economic difficulty it is probable that it will collect $400,000

from the customer. Consequently, the entity concludes that the criterion in paragraph 606-10-25-1(e) is

met based on an estimate of variable consideration of $400,000. In addition, based on an evaluation of

Identify the contract with a customer 25

the contract terms and other facts and circumstances, the entity concludes that the other criteria in

paragraph 606-10-25-1 are also met. Consequently, the entity accounts for the contract with the

customer in accordance with the guidance in this Topic.

It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between a price concession and a collectibility issue. The

ramifications could impact the accounting because one path (a collectibility concern) might lead an entity

to conclude that it does not pass Step 1 for a particular arrangement, while another path (a price

concession) may result in variable consideration and allow the entity to proceed to Step 2 with a lower

transaction price. Judgment will be required to determine which path is appropriate. Ultimately, as

discussed by the TRG,

10

this is not a new area of judgment.

Grant Thornton insight: Price concession versus collectibility issue

ASC 606-10-32-7 provides guidance on factors an entity considers to determine if the promised

consideration is variable because it has offered, or expects to offer, a price concession. It states, in

part, that a price concession exists if either of the following conditions is met:

a. The customer has a valid expectation arising from an entity’s customary business practices,

published policies, or specific statements that the entity will accept an amount of consideration that

is less than the price stated in the contract. That is, it is expected that the entity will offer a price

concession.

b. Other facts and circumstances indicate that the entity’s intention, when entering into the contract

with the customer, is to offer a price concession to the customer.

Other possible indicators that suggest an entity is offering a price concession include

• A business practice of not performing a credit assessment prior to transferring promised goods or

services (for example, a health care provider that is required by law to perform, as described in

ASC 606-10-55-102 through 55-106, Example 3)

• A valid expectation of the customer that the entity will accept less than the contractually stated

amount

• A business practice of continuing to perform despite historical experience suggesting that

collection is not probable

• An arrangement where there is little to no incremental cost associated with fulfilling the

performance obligations (for example, a software provider that incurs little to no reproduction cost

when selling licenses for an existing software product)

• An expectation by the entity at the onset of the arrangement that despite pricing in the contract it

later will offer a price concession (for example, the entity will accept less than the stated price in

order to develop a strategic relationship with a new customer)

Factors that may indicate a customer or pool of customers presents collectibility issues include

• The customer’s financial condition has deteriorated since contract inception.

10

TRG Paper 13, Collectibility.

Identify the contract with a customer 26

• The entity has a pool (portfolio) of homogeneous customers with similar credit profiles, and while it

expects that most will pay amounts when due, it expects that some will not.

There may be other relevant indicators, depending on the facts and circumstances.

See further guidance regarding price concessions, including estimating and reassessing the amount of