Page 1 of 23

Medicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

PRINT-FRIENDLY VERSION

CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2020 American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved.

Applicable FARS/HHSAR apply. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Applicable FARS/

HHSAR Restrictions Apply to Government Use. Fee schedules, relative value units, conversion factors and/or related

components are not assigned by the AMA, are not part of CPT, and the AMA is not recommending their use. The AMA

does not directly or indirectly practice medicine or dispense medical services. The AMA assumes no liability of data

contained or not contained herein.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 2 of 23

Table of Contents

Updates ................................................................................................................................................ 4

Medicare Fraud and Abuse: A Serious Problem That Needs Your Attention ................................. 5

What Is Medicare Fraud? .................................................................................................................... 6

What Is Medicare Abuse? ................................................................................................................... 7

Medicare Fraud and Abuse Laws ....................................................................................................... 8

Federal Civil False Claims Act (FCA) ............................................................................................... 8

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) ............................................................................................................ 9

Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law).......................................................................................... 9

Criminal Health Care Fraud Statute

............................................................................................... 10

Exclusion Statute ........................................................................................................................... 10

Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL) ............................................................................................11

Physician Relationships With Payers

...............................................................................................11

Accurate Coding and Billing ............................................................................................................11

Physician Documentation............................................................................................................... 12

Upcoding

........................................................................................................................................ 12

Physician Relationships With Other Providers ............................................................................... 13

Physician Investments in Health Care Business Ventures............................................................. 13

Physician Recruitment

................................................................................................................... 14

Physician Relationships With Vendors ........................................................................................... 14

Free Samples ................................................................................................................................. 14

Relationships With the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries......................................... 15

Transparency in Physician-Industry Relationships

........................................................................ 15

Federal Open Payments Program ................................................................................................. 15

Conict-of-Interest Disclosures ...................................................................................................... 16

Continuing Medical Education (CME) ............................................................................................ 16

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 3 of 23

Table of Contents (cont.)

Compliance Programs for Physicians ............................................................................................. 17

Medicare Anti-Fraud and Abuse Partnerships and Agencies ....................................................... 17

Health Care Fraud Prevention Partnership (HFPP) ....................................................................... 17

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) 18.........................................................................

Oce of the Inspector General (OIG)

............................................................................................ 19

Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT) .......................................... 19

General Services Administration (GSA) ......................................................................................... 19

Report Suspected Fraud ................................................................................................................... 20

Where to Go for Help ..................................................................................................................... 21

Legal Counsel ................................................................................................................................ 21

Professional Organizations ............................................................................................................ 22

CMS ............................................................................................................................................... 22

OIG................................................................................................................................................. 22

What to Do if You Think You Have a Problem ................................................................................ 22

OIG Provider Self-Disclosure Protocol........................................................................................... 22

CMS Self-Referral Disclosure Protocol (SRDP)............................................................................. 23

Resources .......................................................................................................................................... 23

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 4 of 23

Updates

●

Note: No substantiative content updates.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 5 of 23

Medicare Fraud and Abuse:

A Serious Problem That Needs Your Attention

Although no precise measure of health care fraud exists, those who exploit Federal health care

programs can cost taxpayers billions of dollars while putting beneciaries’ health and welfare at risk.

The impact of these losses and risks magnies as Medicare continues to serve a growing number

of beneciaries.

Most physicians try to work ethically, provide high-quality patient medical care, and submit proper

claims. Trust is core to the physician-patient relationship. Medicare also places enormous trust in

physicians. Medicare and other Federal health care programs rely on physicians’ medical judgment

to treat patients with appropriate, medically necessary services, and to submit accurate claims for

Medicare-covered health care items and services.

You play a vital role in protecting the integrity

of the Medicare Program. To combat fraud

and abuse, you must know how to protect your

organization from engaging in abusive practices

and violations of civil or criminal laws. This booklet

provides the following tools to help protect the

Medicare Program, your patients, and yourself:

●

Medicare fraud and abuse examples

●

Overview of fraud and abuse laws

●

Government agencies and partnerships

dedicated to preventing, detecting, and ghting fraud and abuse

●

Resources for reporting suspected fraud and abuse

Help Fight Fraud by Reporting It

The Oce of Inspector General (OIG)

Hotline accepts tips and complaints

from all sources on potential fraud,

waste, and abuse. V

iew instructional

videos about the OIG Hotline operations,

as well as reporting fraud to the OIG.

Health care professionals who exploit Federal health care programs for illegal, personal, or corporate

gain create the need for laws that combat fraud and abuse and ensure appropriate, quality medical care.

Physicians frequently encounter the following types of business relationships that may raise fraud and

abuse concerns:

●

Relationships with payers

●

Relationships with fellow physicians and other providers

●

Relationships with vendors

These key relationships and other issues addressed in this booklet apply to all physicians, regardless

of specialty or practice setting.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 6 of 23

What Is Medicare Fraud?

Medicare fraud typically includes any of the following:

●

Knowingly submitting, or causing to be submitted, false

claims or making misrepresentations of fact to obtain a

Federal health care payment for which no entitlement

would otherwise exist

●

Knowingly soliciting, receiving, oering, or paying

remuneration (e.g., kickbacks, bribes, or rebates) to

induce or reward referrals for items or services

reimbursed by Federal health care programs

●

Making prohibited referrals for certain designated health services

Case Studies

To learn about real-life cases of

Medicare fraud and abuse and

the consequences for culprits,

visit the Medicare Fraud Strike

Force webpage.

Anyone can commit health care fraud. Fraud schemes range from solo ventures to widespread

activities by an institution or group. Even organized crime groups inltrate the Medicare Program and

operate as Medicare providers and suppliers. Examples of Medicare fraud include:

●

Knowingly billing for services at a level of complexity higher than services actually provided or

documented in the medical records

●

Knowingly billing for services not furnished, supplies not provided, or both, including falsifying

records to show delivery of such items

●

Knowingly ordering medically unnecessary items or services for patients

●

Paying for referrals of Federal health care program beneciaries

●

Billing Medicare for appointments patients fail to keep

Defrauding the Federal Government and its programs is illegal. Committing Medicare fraud

exposes individuals or entities to potential criminal, civil, and administrative liability, and may lead to

imprisonment, nes, and penalties.

Criminal and civil penalties for Medicare fraud reect the serious harms associated with health

care fraud and the need for aggressive and appropriate intervention. Providers and health care

organizations involved in health care fraud risk being excluded from participating in all Federal health

care programs and losing their professional licenses.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 7 of 23

What Is Medicare Abuse?

Abuse describes practices that may directly or indirectly result in unnecessary costs to the Medicare

Program. Abuse includes any practice that does not provide patients with medically necessary

services or meet professionally recognized standards of care.

The dierence between “fraud” and “abuse” depends on specic facts, circumstances, intent,

and knowledge.

Examples of Medicare abuse include:

●

Billing for unnecessary medical services

●

Charging excessively for services or supplies

●

Misusing codes on a claim, such as upcoding or unbundling codes. Upcoding is when a provider

assigns an inaccurate billing code to a medical procedure or treatment to increase reimbursement.

Medicare abuse can also expose providers to criminal and civil liability.

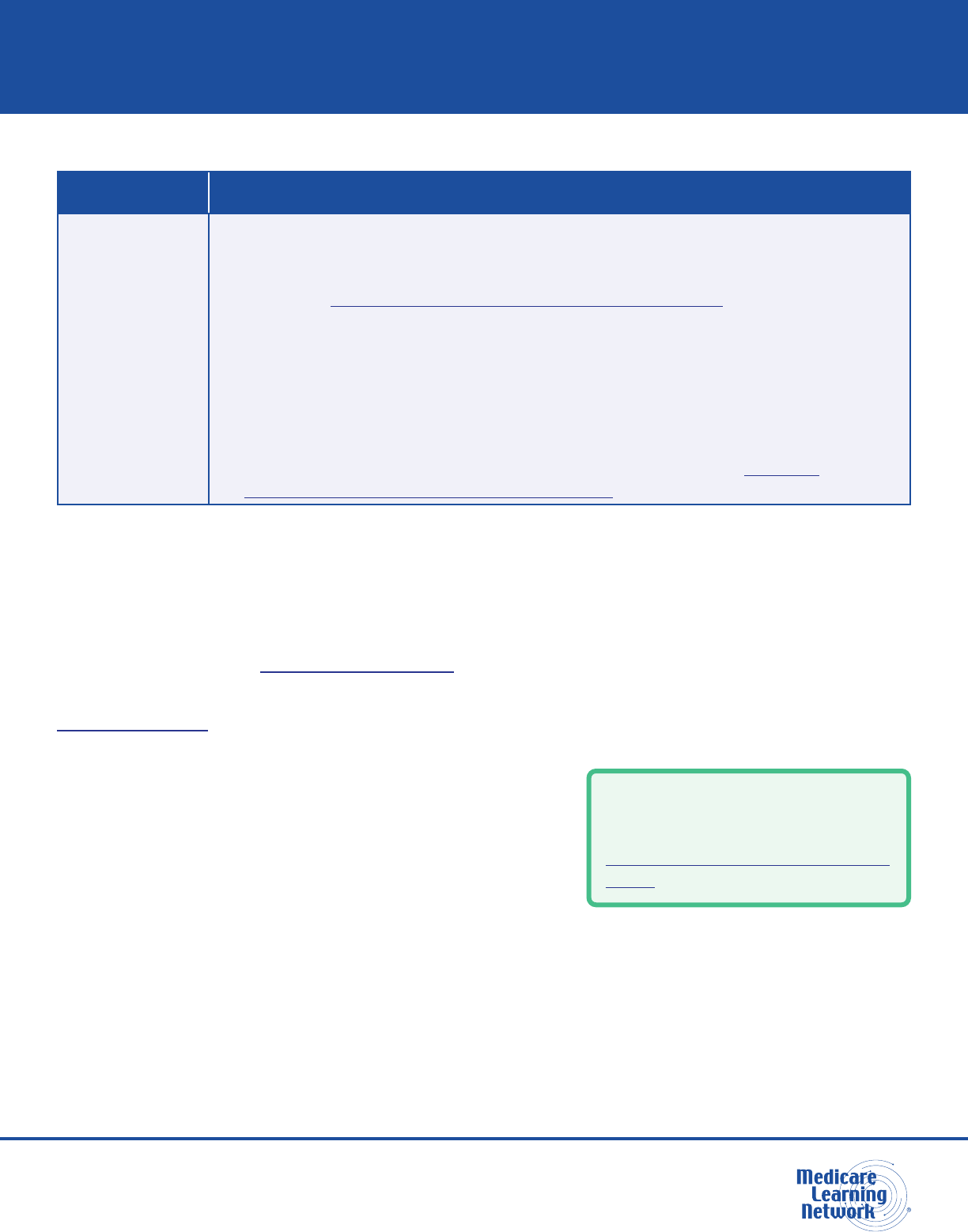

Program integrity includes a range of activities targeting various causes of improper payments. Figure 1

shows examples along the range of possible types of improper payments.

Figure 1. Types of Improper Payments*

MISTAKES

RESULT IN ERRORS: Incorrect

coding that is not wide spread

INEFFICIENCIES

RESULT IN WASTE:

Ordering excessive diagnostic tests

BENDING

THE RULES

RESULTS IN ABUSE:

Improper billing practices (like upcoding)

INTENTIONAL

DECEPTIONS

RESULT IN FRAUD:

Billing for services or supplies that were not provided

*The types of improper payments in Figure 1 are strictly examples for educational purposes, and the precise characterization

of any type of improper payment depends on a full analysis of specic facts and circumstances. Providers who engage

in incorrect coding, ordering excessive diagnostic tests, upcoding, or billing for services or supplies not provided may be

subject to administrative, civil, or criminal liability.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 8 of 23

Medicare Fraud and Abuse Laws

Federal laws governing Medicare fraud and abuse

include the:

●

False Claims Act (FCA)

●

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

●

Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law)

●

Social Security Act, which includes the Exclusion

Statute and the Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL)

●

United States Criminal Code

Fraud and Abuse in Medicare

Part C, Part D, and Medicaid

In addition to Medicare Part A and

Part B, Medicare Part C and Part D

and Medicaid programs prohibit the

fraudulent conduct addressed by

these laws.

These laws specify the criminal, civil, and administrative penalties and remedies the government may

impose on individuals or entities that commit fraud and abuse in the Medicare and Medicaid Programs.

Violating these laws may result in nonpayment of claims, Civil Monetary Penalties (CMP), exclusion

from all Federal health care programs, and criminal and civil liability.

Government agencies, including the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), the U.S. Department of

Health & Human Services (HHS), the HHS Oce of Inspector General (OIG), and the Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), enforce these laws.

Federal Civil False Claims Act (FCA)

The civil FCA, 31 United States Code (U.S.C.) Sections 3729–3733, protects the Federal Government

from being overcharged or sold substandard goods or services. The civil FCA imposes civil liability on

any person who knowingly submits, or causes the submission of, a false or fraudulent claim to the

Federal Government.

The terms “knowing” and “knowingly” mean a person has actual knowledge of the information or acts

in deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of the information related to the claim.

No specic intent to defraud is required to violate the civil FCA.

Examples: A physician knowingly submits claims to Medicare for medical services not provided or for

a higher level of medical services than actually provided.

Penalties: Civil penalties for violating the civil FCA may include recovery of up to three times the

amount of damages sustained by the Government as a result of the false claims, plus nancial

penalties per false claim led.

Additionally, under the criminal FCA, 18 U.S.C. Section 287, individuals or entities may face criminal

penalties for submitting false, ctitious, or fraudulent claims, including nes, imprisonment, or both.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 9 of 23

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)

The AKS, 42 U.S.C. Section 1320a-7b(b), makes it a crime

to knowingly and willfully oer, pay, solicit, or receive any

remuneration directly or indirectly to induce or reward patient

referrals or the generation of business involving any item

or service reimbursable by a Federal health care program.

When a provider oers, pays, solicits, or receives unlawful

remuneration, the provider violates the AKS.

Anti-Kickback

Statute vs. Stark Law

Refer to the Comparison of the

Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark

Law handout.

NOTE: Remuneration includes anything of value, such as cash, free rent, expensive hotel stays and

meals, and excessive compensation for medical directorships or consultancies.

Example: A provider receives cash or below-fair-market-value rent for medical oce space in

exchange for referrals.

Penalties: Criminal penalties and administrative sanctions for violating the AKS may include nes,

imprisonment, and exclusion from participation in the Federal health care program. Under the CMPL,

penalties for violating the AKS may include three times the amount of the kickback.

The “safe harbor” regulations, 42 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) Section 1001.952, describe

various payment and business practices that, although they potentially implicate the AKS, are not

treated as oenses under the AKS if they meet certain requirements specied in the regulations.

Individuals and entities remain responsible for complying with all other laws, regulations, and

guidance that apply to their businesses.

Physician Self-Referral Law (Stark Law)

The Physician Self-Referral Law, 42 U.S.C. Section 1395nn, often called the Stark Law, prohibits

a physician from referring patients to receive “designated health services” payable by Medicare or

Medicaid to an entity with which the physician or a member of the physician’s immediate family has a

nancial relationship, unless an exception applies.

Example: A physician refers a beneciary for a designated health service to a clinic where the

physician has an investment interest.

Penalties: Penalties for physicians who violate the Stark Law may include nes, CMPs for each service,

repayment of claims, and potential exclusion from participation in the Federal health care programs.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 10 of 23

Criminal Health Care Fraud Statute

The Criminal Health Care Fraud Statute, 18 U.S.C. Section 1347 prohibits knowingly and willfully

executing, or attempting to execute, a scheme or lie in connection with the delivery of, or payment for,

health care benets, items, or services to either:

●

Defraud any health care benet program

●

Obtain (by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises) any of the money

or property owned by, or under the control of, any health care benet program

Example: Several doctors and medical clinics conspire in a coordinated scheme to defraud the

Medicare Program by submitting medically unnecessary claims for power wheelchairs.

Penalties: Penalties for violating the Criminal Health Care Fraud Statute may include nes,

imprisonment, or both.

Exclusion Statute

The Exclusion Statute, 42 U.S.C. Section 1320a-7, requires the OIG to exclude individuals and entities

convicted of any of the following oenses from participation in all Federal health care programs:

●

Medicare or Medicaid fraud, as well as any other oenses related to the delivery of items or

services under Medicare or Medicaid

●

Patient abuse or neglect

●

Felony convictions for other health care-related fraud, theft, or other nancial misconduct

●

Felony convictions for unlawful manufacture, distribution, prescription, or dispensing

controlled substances

The OIG also may impose permissive exclusions on other grounds, including:

●

Misdemeanor convictions related to health care fraud other than Medicare or Medicaid fraud, or

misdemeanor convictions for unlawfully manufacturing, distributing, prescribing, or dispensing

controlled substances

●

Suspension, revocation, or surrender of a license to provide health care for reasons bearing on

professional competence, professional performance, or nancial integrity

●

Providing unnecessary or substandard services

●

Submitting false or fraudulent claims to a Federal health care program

●

Engaging in unlawful kickback arrangements

●

Defaulting on health education loan or scholarship obligations

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 11 of 23

Excluded providers may not participate in the Federal health care programs for a designated period.

If you are excluded by OIG, then Federal health care programs, including Medicare and Medicaid,

will not pay for items or services that you furnish, order, or prescribe. Excluded providers may not bill

directly for treating Medicare and Medicaid patients, and an employer or a group practice may not

bill for an excluded provider’s services. At the end of an exclusion period, an excluded provider must

seek reinstatement; reinstatement is not automatic.

The OIG maintains a list of excluded parties called the List of Excluded Individuals/Entities (LEIE).

Civil Monetary Penalties Law (CMPL)

The CMPL, 42 U.S.C. Section 1320a-7a, authorizes OIG to seek CMPs and sometimes exclusion for

a variety of health care fraud violations. Dierent amounts of penalties and assessments apply based

on the type of violation. CMPs also may include an assessment of up to three times the amount

claimed for each item or service, or up to three times the amount of remuneration oered, paid,

solicited, or received. Violations that may justify CMPs include:

●

Presenting a claim you know, or should know, is for an item or service not provided as claimed or

that is false and fraudulent

●

Violating the AKS

●

Making false statements or misrepresentations on applications or contracts to participate in the

Federal health care programs

CMP Ination Adjustment

Each year, the Federal Government adjusts all CMPs for ination. The adjusted amounts apply to

civil penalties assessed after August 1, 2016, and violations after November 2, 2015. Refer to

45 C.F.R. Section 102.3

for the yearly ination adjustments.

Physician Relationships With Payers

The U.S. health care system relies heavily on third-party payers to pay the majority of medical bills on

behalf of patients. When the Federal Government covers items or services rendered to Medicare

and Medicaid beneciaries, the Federal fraud and abuse laws apply. Many similar State fraud and

abuse laws apply to your provision of care under state-nanced programs and to private-pay patients.

Accurate Coding and Billing

As a physician, payers trust you to provide medically necessary, cost-eective, quality care. You exert

signicant inuence over what services your patients get. You control the documentation describing

services they receive, and your documentation serves as the basis for claims you submit. Generally,

Medicare pays claims based solely on your representations in the claims documents.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 12 of 23

When you submit a claim for services provided to a Medicare beneciary, you are ling a bill

with the Federal government and certifying you earned the payment requested and complied

with the billing requirements. If you knew or should have known the submitted claim was false,

then the attempt to collect payment is illegal. Examples of improper claims include:

●

Billing codes that reect a more severe illness than actually existed or a more expensive treatment

than was provided

●

Billing medically unnecessary services

●

Billing services not provided

●

Billing services performed by an improperly supervised or unqualied employee

●

Billing services performed by an employee excluded from participation in the Federal health

care programs

●

Billing services of such low quality they are virtually worthless

●

Billing separately for services already included in a global fee, like billing an evaluation and

management service the day after surgery

Physician Documentation

Maintain accurate and complete medical records and documentation of the services you provide.

Ensure your documentation supports the claims you submit for payment. Good documentation

practices help to ensure your patients get appropriate care and allow other providers to rely

on your records for patients’ medical histories.

The Medicare Program may review beneciaries’ medical records. Good documentation helps

address any challenges raised about the integrity of your claims. You may have heard the saying

regarding malpractice litigation: “If you didn’t document it, it’s the same as if you didn’t do it.”

The

same can be said for Medicare billing.

Accuracy of Medical Record Documentation

For more information on physician documentation, refer to the Evaluation and Management

Services guide, Complying With Medical Record Documentation Requirements fact sheet, and

an OIG video on the Importance of Documentation.

Upcoding

Medicare pays for many physician services using Evaluation and Management (E/M) codes. New

patient visits generally require more time than established patient follow-up visits. Medicare pays new

patient E/M codes at higher reimbursement rates than established patient E/M codes.

Example: Billing an established patient follow-up visit using a higher-level E/M code, such as a

comprehensive new-patient oce visit.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 13 of 23

Another example of E/M upcoding is misusing modier –25. Modier –25 allows additional payment

for a signicant, separately identiable E/M service provided on the same day of a procedure or

other service. Upcoding occurs when a provider uses modier –25 to claim payment for a medically

unnecessary E/M service, an E/M service not distinctly separate from the procedure or other service

provided, or an E/M service not above and beyond the care usually associated with the procedure.

CPT only copyright 2020 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Physician Relationships With Other Providers

Anytime a health care business oers you something for free or below fair market value, ask

yourself, “Why?”

Physician Investments in Health Care Business Ventures

Some physicians who invest in health care business

ventures with outside parties (for instance, imaging centers,

laboratories, equipment vendors, or physical therapy clinics)

refer more patients for the services provided by those

parties than physicians who do not invest. These business

relationships may improperly inuence or distort physician

decision-making and result in the improper steering of

patients to a therapy or service where a physician has a

nancial interest.

Excessive and medically unnecessary referrals waste

Federal Government resources and can expose

Medicare beneciaries to harm from unnecessary

services. Many of these investment relationships have

serious legal risks under the AKS and Stark Law.

Physician Investments

For more information on physician

investments, refer to the OIG’s:

●

Special Fraud Alert:

Joint Venture Arrangements

●

Special Fraud Alert:

Physician-Owned Entities

●

Special Advisory Bulletin:

Contractual Joint Ventures

If someone invites you to invest in a health care business whose products you might order or to which

you might refer your patients, ask yourself the following questions. If you answer “yes” to any of them,

you should carefully consider the reasons for your investment.

●

Is the investment interest oered to you in exchange for a nominal capital contribution?

●

Is the ownership share oered to you larger than your share of the aggregate capital contributions

made to the venture?

●

Is the venture promising you high rates of return for little or no nancial risk?

●

Is the venture, or any potential business partner, oering to loan you the money to make your

capital contribution?

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 14 of 23

●

Are you promising or guaranteeing to refer patients or order items or services from the venture?

●

Are you more likely to refer patients for the items and services provided by the venture if you make

the investment?

●

Does the venture have sucient capital from other sources to fund its operations?

Physician Recruitment

Hospitals and other health systems may provide a physician-recruitment incentive to induce you to

relocate to the hospital’s geographic area, join its medical sta, and establish a practice to help serve a

community’s medical needs. Often, such recruitment eorts ll a legitimate “clinical gap” in a medically

underserved area where attracting physicians may be dicult in the absence of nancial incentives.

However, in some communities, especially ones with multiple hospitals, hospitals ercely compete

for patients. To gain referrals, some hospitals may oer illegal incentives to you or to the established

physician practice you join in the hospital’s community. This means the competition for your loyalty

can cross the line into an illegal arrangement with legal consequences for you and the hospital.

A hospital may pay you a fair market-value salary as an employee or pay you fair market value for

specic services you render to the hospital as an independent contractor. However

, the hospital may

not oer you money, provide you free or below-market rent for your medical oce, or engage in

similar activities designed to inuence your referral decisions. Admit your patients to the hospital

best suited to care for their medical conditions or to the hospital your patients select based on

their preference or insurance coverage.

Within very specic parameters of the Stark Law and subject to compliance with the AKS, hospitals

may provide relocation assistance and practice support under a properly structured recruitment

arrangement to assist you in establishing a practice in the hospital’s community

. If a hospital or

physician practice separately or jointly recruit you as a new physician to the community, they may

oer a recruitment package. Unless you are a hospital employee, you cannot negotiate for benets

in exchange for an implicit or explicit promise to admit your patients to a specic hospital or practice

setting. Seek knowledgeable legal counsel if a prospective business relationship requires you to

admit patients to a specic hospital or practice group.

Physician Relationships With Vendors

Free Samples

Many drug and biologic companies provide free product samples to physicians. It is legal to give

these samples to your patients free of charge, but it is illegal to sell the samples. The Federal

Government has prosecuted physicians for billing Medicare for free samples. If you choose to accept

free samples, you need reliable systems in place to safely store the samples and ensure samples

remain separate from your commercial stock.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 15 of 23

Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries Codes of Ethics

Both the pharmaceutical industry, through the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of

America (PhRMA), and the medical device industry, through the Advanced Medical Technology

Association (AdvaMed), adopted codes of ethics regarding relationships with health care

professionals. For more information, visit the PhRMA Code on Interactions With Health Care

Professionals and the AdvaMed Code of Ethics.

Relationships With the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries

Some pharmaceutical and device companies use sham consulting agreements and other

arrangements to buy physician loyalty to their products. As a practicing physician, you may have

opportunities to work as a consultant or promotional speaker for the drug or device industry. For every

nancial relationship oered to you, evaluate the link between the services you can provide and the

compensation you will get. Test the appropriateness of any proposed relationship by asking yourself

the following questions:

●

Does the company really need your specic expertise or input?

●

Does the company’s monetary compensation to you represent a fair, appropriate, and

commercially reasonable exchange for your services?

●

Is it possible the company is paying for your loyalty, so you prescribe its drugs or use its devices?

If your contribution is your time and eort or your ability to generate useful ideas and the payment

you receive is fair-market-value compensation for your services without regard to referrals, then,

depending on the circumstances, you may legitimately serve as a bona de consultant. If your

contribution is your ability to prescribe a drug, use a medical device, or refer patients for

services or supplies, the potential consulting relationship likely is one you should avoid as it

could violate fraud and abuse laws.

Transparency in Physician-Industry Relationships

Although some physicians believe free lunches, subsidized trips, and gifts do not aect their medical

judgment, research shows these types of privileges can inuence prescribing practices.

Federal Open Payments Program

The Federal Open Payments Program

highlights nancial relationships among

physicians, teaching hospitals, and drug

and device manufacturers. Drug, device,

and biologic companies must publicly

report nearly all gifts or payments made

to physicians.

Industry Relationships

For more information on distinguishing between

legitimate and questionable industry relationships,

refer to the OIG’s Compliance Program Guidance for

Pharmaceutical Manufacturers.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 16 of 23

The Federal Open Payments Program requires pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers

to publicly report payments to physicians and teaching hospitals. CMS posts Open Payments data

on June 30 each year, including payments or other transfers of value and ownership or investment

interest reports. CMS closely monitors this process to ensure integrity in the reported data.

Publicly available information about you includes:

●

Activities such as speaking engagements

●

Educational materials such as text books or journal reprints

●

Entertainment

●

Gifts

●

Meals

●

Participation in a paid advisory board

●

Travel expenses

CMS does not require physicians to register with, or send information to, Federal Open Payments.

However, CMS encourages your help to ensure accurate information by doing the following:

●

Register with the Open Payments Program and subscribe to the electronic mailing list for

Program updates

●

Review the information manufacturers and GPOs submit on your behalf

●

Work with manufacturers and GPOs to settle data issues about your Open Payments prole

Conict-of-Interest Disclosures

Many of the relationships discussed in this booklet are subject to conict-of-interest disclosure policies.

Even if the relationships are legal, you may be obligated to disclose their existence. Rules about

disclosing and managing conicts of interest come from a variety of sources, including grant funders,

such as states, universities, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and from the U.S. Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) when you submit data to support marketing approval for new drugs,

devices, or biologics.

If you are uncertain whether a conict exists, ask yourself if you would want the arrangement

to appear in the news.

Continuing Medical Education (CME)

You are responsible for your CME to maintain State licensure, hospital privileges, and board

certication. Drug and device manufacturers sponsor many educational opportunities for physicians.

It is important to distinguish between CME sessions that are educational and sessions that

constitute marketing by a drug or device manufacturer. If speakers recommend prescribing a

drug when there is no FDA approval or prescribing a drug for children when the FDA has approved

only adult use, independently seek out the empirical data supporting these recommendations.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 17 of 23

NOTE: Although physicians may prescribe drugs for o-label uses, it is illegal under the Federal

Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act for drug manufacturers to promote o-label drug use.

FDA Bad Ad Program

Drugs, biologics, medical devices, and other promotional advertisements must be truthful, not

misleading, and limited to approved uses. The FDA requests physicians’ assistance in identifying

misleading advertisements through its Bad Ad Program. If you spot advertising violations, report

them to the FDA by calling 877-RX-DDMAC (877-793-3622) or by emailing [email protected].

Watch What To Do About Misleading Drug Ads for more information.

Compliance Programs for Physicians

Physicians treating Medicare beneciaries should establish a compliance program. Establishing and

following a compliance program helps physicians avoid fraudulent activities and submit accurate claims.

The following seven components provide a solid basis for a physician practice compliance program:

1. Conduct internal monitoring and auditing

2. Implement compliance and practice standards

3. Designate a compliance ocer or contact

4. Conduct appropriate training and education

5. Respond appropriately to detected oenses

and develop corrective action

6. Develop open lines of communication with employees

7. Enforce disciplinary standards through well-publicized guidelines

Compliance Programs

for Physicians

For more information on compliance

programs for physicians, visit the OIG

Compliance webpage or watch this

Compliance Program Basics video.

Medicare Anti-Fraud and

Abuse Partnerships and Agencies

Government agencies partner to ght fraud and abuse, uphold the integrity of the Medicare Program,

save and recoup taxpayer funds, reduce health care costs, and improve the quality of health care.

Health Care Fraud Prevention Partnership (HFPP)

The HFPP is a voluntary public-private partnership among the federal government, State agencies, law

enforcement, private health insurance plans, and health care anti-fraud associations. The HFPP fosters

a proactive approach to detect and prevent health care fraud through data and information sharing.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 18 of 23

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

CMS is the Federal agency within HHS that administers the Medicare Program, Medicaid Program,

State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

(CLIA), and several other health-related programs.

To prevent and detect fraud and abuse, CMS works with individuals, entities, and law enforcement

agencies, including:

●

Accreditation Organizations (AO)

●

Medicare beneciaries and caregivers

●

Physicians, suppliers, and other health care providers

●

State and Federal law enforcement agencies, including the OIG, Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI), DOJ, State Medicaid Agencies, and Medicaid Fraud Control Units (MFCU)

To support its eorts to prevent, detect, and investigate potential Medicare fraud and abuse, CMS

also partners with a selection of contractors.

Table 1. Contractor Eorts to Prevent, Detect, and Investigate Fraud and Abuse

Contractor Role

Comprehensive Error Rate Testing

(CERT) Contractors

Help calculate the Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) improper

payment rate by reviewing claims to determine if they were

paid properly

Medicare Administrative Contractors

(MAC)

Process claims and enroll providers and suppliers

Medicare Drug Integrity Contractors

(MEDIC)

Monitor fraud, waste, and abuse in the Medicare Parts C

and D Programs. Beginning January 2, 2019, the Centers for

Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will have two Medicare

Drug Integrity Contractors (MEDICs), the National Benet

Integrity (NBI MEDIC) and the Investigations (I-MEDIC).

Recovery Audit Program

Recovery Audit Contractors (RACs)

Reduce improper payments by detecting and collecting

overpayments and identifying underpayments

Zone Program Integrity Contractors

(ZPIC)

Formerly called Program Safeguard

Contractors (PSC)

Investigate potential fraud, waste, and abuse for Medicare

Parts A and B; Durable Medical Equipment Prosthetics,

Orthotics, and Supplies; and Home Health and Hospice

Unied Program Integrity

Contractors (UPIC)

Combine and integrate Medicare and Medicaid Program

Integrity audit and investigation work functions into a

single contract

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 19 of 23

Within CMS, the Center for Program Integrity (CPI) promotes the integrity of Medicare through audits,

policy reviews, and identifying and monitoring program vulnerabilities. CPI oversees CMS’ collaboration

with key stakeholders on program integrity issues related to detecting, deterring, monitoring, and

combating fraud and abuse.

In 2010, HHS and CMS launched the Fraud Prevention System (FPS), a state-of-the-art predictive

analytics technology that runs predictive algorithms and other analytics nationwide on all Medicare

FFS claims prior to payment to detect potentially suspicious claims and patterns that may constitute

fraud and abuse.

In 2012, CMS created the Program Integrity Command Center to bring together Medicare and

Medicaid ocials, clinicians, policy experts, CMS fraud investigators, and the law enforcement

community, including the OIG and FBI. The Command Center gathers these experts to develop and

improve intricate predictive analytics that identify fraud and mobilize a rapid response. CMS connects

instantly with its eld oces to evaluate fraud allegations through real-time investigations. Previously,

nding substantiating evidence of a fraud allegation took days or weeks; now it can take only hours.

Oce of the Inspector General (OIG)

The OIG protects the integrity of HHS’ programs and the health and welfare of program beneciaries.

The OIG operates through a nationwide network of audits, investigations, inspections, evaluations,

and other related functions. The Inspector General is authorized to, among other things, exclude

individuals and entities who engage in fraud or abuse from participation in all Federal health care

programs, and to impose CMPs for certain violations.

Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT)

The DOJ, OIG, and HHS established HEAT to build and strengthen existing programs combatting

Medicare fraud while investing new resources and technology to prevent and detect fraud and abuse.

HEAT expanded the DOJ-HHS Medicare Fraud Strike Force, which targets emerging or migrating

fraud schemes, including fraud by criminals masquerading as health care providers or suppliers.

General Services Administration (GSA)

The GSA consolidated several Federal procurement systems into one new system: the System for

Award Management (SAM). SAM includes information on entities that are:

●

Debarred or proposed for debarment

●

Disqualied from certain types of Federal nancial and non-nancial assistance and benets

●

Disqualied from receiving Federal contracts or certain subcontracts

●

Excluded or suspended from the Medicare Program

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 20 of 23

Report Suspected Fraud

Table 2. Where Should You Report Fraud and Abuse?

If You Are a… Report Fraud to…

Medicare

Beneciary

For any complaint:

●

CMS Hotline

:

Phone: 1-800-MEDICARE (1-800-633-4227) or TTY 1-877-486-2048 AND

●

OIG Hotline:

Phone: 1-800-HHS-TIPS (1-800-447-8477) or TTY 1-800-377-4950

Fax: 1-800-223-8164

Online: Forms.oig.hhs.gov/hotlineoperations/index.asp

Mail: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Oce of Inspector General

ATTN: OIG Hotline Operations

P.O. Box 23489

Washington, DC 20026

For Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage) or Part D (Prescription Drug Plans)

complaints:

●

1-877-7SafeRx (1-877-772-3379)

Medicare

Provider

●

OIG Hotline:

Phone: 1-800-HHS-TIPS (1-800-447-8477) or TTY 1-800-377-4950

Fax: 1-800-223-8164

Online:

Forms.oig.hhs.gov/hotlineoperations/index.asp

Mail: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Oce of Inspector General

ATTN: OIG Hotline Operations

P.O. Box 23489

Washington, DC 20026

OR

●

Contact your MAC

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 21 of 23

Table 2. Where Should You Report Fraud and Abuse? (cont.)

If You Are a… Report Fraud to…

Medicaid

Beneciary or

Provider

●

OIG Hotline:

Phone: 1-800-HHS-TIPS (1-800-447-8477) or TTY 1-800-377-4950

Fax: 1-800-223-8164

Online:

Forms.oig.hhs.gov/hotlineoperations/index.asp

Mail: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Oce of Inspector General

ATTN: OIG Hotline Operations

P.O. Box 23489

Washington, DC 20026

OR

●

Your Medicaid State Agency: State MFCUs are listed in the National

Association of Medicaid Fraud Control Units (NAMFCU)

If you prefer to report fraud and abuse anonymously to the OIG Hotline, the OIG record systems

collect no information that could trace the complaint to you. However, lack of contact information may

prevent OIG’s comprehensive review of the complaint, so the OIG encourages you to provide contact

information for possible follow-up.

Medicare and Medicaid beneciaries can learn more about protecting themselves and spotting fraud

by contacting their local Senior Medicare Patrol (SMP) program.

For questions about Medicare billing procedures, billing errors, or questionable billing practices,

contact your MAC.

Where to Go for Help

When considering a billing practice; entering into a particular

business venture; or pursuing any employment, consulting,

or other personal services relationship, evaluate the

arrangement for potential compliance problems. Consider

the following list of resources to assist with your evaluation:

Medical Identity Theft

For more information, refer to the

Medical Identity Theft & Medicare

Fraud brochure.

Legal Counsel

●

Experienced health care lawyers can analyze your issues and provide a legal evaluation and risk

analysis of the proposed venture, relationship, or arrangement.

●

The Bar Association in your state may maintain a directory of local attorneys who practice in the

health care eld.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 22 of 23

Professional Organizations

●

Your state or local medical society may be a good resource for issues aecting physicians and

may keep listings of health care attorneys in your area.

●

Your specialty society may have information on additional risk areas specic to your type of practice.

CMS

●

MAC medical directors are a valuable source of information on Medicare coverage policies and

appropriate billing practices. Contact your MAC for more information.

●

CMS issues advisory opinions to parties seeking advice on the Stark Law. For more information,

visit the CMS Advisory Opinions webpage.

OIG

●

For more information on OIG compliance recommendations and discussions of fraud and abuse

risk area, refer to OIG’s Compliance Program Guidance. Visit OIG’s Compliance Education

Materials for more information.

●

OIG issues advisory opinions to parties who seek advice on the application of the Anti-Kickback

Statute, Civil Monetary Penalties Law, and Exclusion Statute. For more information, visit the

OIG Advisory Opinions webpage.

What to Do if You Think You Have a Problem

If you think you are engaged in a problematic relationship or have been following billing practices you

now realize are wrong:

●

Immediately stop submitting problematic bills

●

Seek knowledgeable legal counsel

●

Determine what money you collected in error from patients and from the Federal health care

programs and report and return overpayments

●

Unwind the problematic investment by freeing yourself from your involvement

●

Separate yourself from the suspicious relationship

●

Consider using OIG’s or CMS’ self-disclosure protocols, as applicable

OIG Provider Self-Disclosure Protocol

The OIG Provider Self-Disclosure Protocol is a vehicle for providers to voluntarily disclose self-discovered

evidence of potential fraud. The protocol allows providers to work with the Government to avoid

the costs and disruptions associated with a Government-directed investigation and civil or

administrative litigation.

MLN BookletMedicare Fraud & Abuse: Prevent, Detect, Report

ICN MLN4649244 January 2021

Page 23 of 23

CMS Self-Referral Disclosure Protocol (SRDP)

The SRDP enables health care providers and suppliers to self-disclose actual or potential Stark

Law violations.

Resources

●

CMS Fraud Prevention Toolkit

●

Center for Program Integrity: Protecting the Medicare & Medicaid Programs from Fraud,

Waste & Abuse

●

Help Fight Medicare Fraud

●

Medicaid Program Integrity Education

●

OIG Contact Information

●

OIG Fraud Information

●

Physician Self-Referral

Medicare Learning Network® Content Disclaimer, Product Disclaimer, and Department of Health & Human Services Disclosure

The Medicare Learning Network®, MLN Connects®, and MLN Matters® are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department

of Health & Human Services (HHS).