LEADING WITH MEANING: BENEFICIARY CONTACT,

PROSOCIAL IMPACT, AND THE PERFORMANCE EFFECTS OF

TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP

ADAM M. GRANT

University of Pennsylvania

Although transformational leadership is thought to increase followers’ performance by

motivating them to transcend self-interest, rhetoric alone may not be sufficient. I

propose that transformational leadership is most effective in motivating followers

when they interact with the beneficiaries of their work, which highlights how the

vision has meaningful consequences for other people. In a quasi-experimental study,

beneficiary contact strengthened the effects of transformational leadership on call

center employees’ sales and revenue. A survey study with government employees

extended these results, supporting a moderated mediation model with perceived

prosocial impact. Relational job design can enhance the motivational effects of trans-

formational leadership.

A fundamental task for leaders is to motivate

followers to accomplish great things (Vroom & Jago,

2007). According to theories of transformational

and charismatic leadership, leaders achieve this

task by engaging in inspirational behaviors such as

articulating a compelling vision, emphasizing col-

lective identities, expressing confidence and opti-

mism, and referencing core values and ideals (Bass,

1985; Burns, 1978; House, 1977; Shamir, House, &

Arthur, 1993). Evidence suggests that when leaders

engage in these visionary behaviors, followers set

more value-congruent goals (Bono & Judge, 2003)

and experience their work as more meaningful (Pic-

colo & Colquitt, 2006; Purvanova, Bono, & Dziewe-

czynski, 2006). As a result, research has shown that

on average, transformational leadership correlates

positively with followers’ motivation and job per-

formance (Judge & Piccolo, 2004).

However, evidence suggests that transforma-

tional leadership does not always motivate higher

performance among followers. Inconsistent effects

of transformational leadership on followers’ perfor-

mance have emerged in field experiments in Cana-

dian banks (Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, 1996) and

the Israeli military (Dvir, Eden, Avolio, & Shamir,

2002), as well as in laboratory experiments using

business simulation tasks (Bono & Judge, 2003;

Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996). One explanation for

this inconsistent evidence is that when transforma-

tional leaders articulate meaningful visions, they

face challenges in making these visions a tangible

reality. Indeed, Kirkpatrick and Locke (1996: 37)

suggested that leaders need to take steps “to ensure

that the vision is not simply rhetoric.”

In particular, a central purpose of transforma-

tional leadership is to articulate a vision that fo-

cuses employees’ attention on their contributions

to others. At its core, transformational leadership

involves “motivating followers to transcend their

own self-interests for the sake of the team, the or-

ganization or the larger polity” (Shamir et al., 1993:

579). To do so, transformational leaders often strive

to highlight the prosocial impact of the vision—

how it has meaningful consequences for other peo-

ple (Grant, 2007; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003).

However, the broad rhetoric that makes a vision

inspiring and connects it to core values may render

the prosocial impact of the vision less tangible. As

Shamir and colleagues (1993: 583) noted, transfor-

mational leadership “tends to emphasize vague and

distal goals,” yet prosocial impact is most tangible

when employees have vivid, proximal exposure to

the human beings affected by their contributions

(Grant, Campbell, Chen, Cottone, Lapedis, & Lee,

2007; Turner, Hadas-Halperin, & Raveh, 2008).

Thus, to establish the prosocial impact of a vision,

transformational leaders may need more than

words (see Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996).

For meaningful feedback and suggestions, I thank Ja-

son Colquitt, three anonymous reviewers, Drew Carton,

Christina Fong, Dave Hofmann, Sim Sitkin, and the fac-

ulty members and doctoral students at Cornell Univer-

sity, especially Lisa Dragoni. For assistance with data

collection, I am grateful to Stan Campbell, Jenny Deveau,

Chad Friedlein, Howard Heevner, Ted Henifin, and Jon-

athan Tugman.

Editor’s note: The manuscript for this article was ac-

cepted for publication during the term of AMJ’s previous

editor-in-chief, R. Duane Ireland.

娀 Academy of Management Journal

2012, Vol. 55, No. 2, 458–476.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0588

458

Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s express

written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles for individual use only.

Although transformational leadership research

has focused on the inspirational, visionary mes-

sages that leaders deliver to followers, scholars

have recognized that leaders can also influence per-

formance by altering the structural features of fol-

lowers’ jobs (Piccolo, Greenbaum, Den Hartog, &

Folger, 2010). Accordingly, I expect that job design

is likely to play an important role in moderating the

performance effects of transformational leadership.

Rather than focusing on the traditional task charac-

teristics of jobs (Hackman & Oldham, 1976, 1980), I

focus on the social characteristics of jobs—the in-

terpersonal interactions and relationships in which

work is embedded (Grant & Parker, 2009; Morgeson

& Humphrey, 2006). Recently, scholars studying

relational job design have proposed that leaders

can enhance perceptions of prosocial impact not

only by engaging in transformational behaviors, but

also by modifying the connections between em-

ployees and the beneficiaries of their work (Grant,

2007; Grant et al., 2007). Most organizations have

prime beneficiaries—clients, customers, patients,

and other recipients or end users of their core prod-

ucts and services (Blau & Scott, 1962; Katz & Kahn,

1966). Evidence from field and laboratory studies

demonstrates that even when employees are re-

sponsible for a meaningful job or task, they gain a

stronger awareness of its prosocial impact when

they have contact with the beneficiary; this benefi-

ciary contact enables them to see the tangible,

meaningful consequences of their actions for a liv-

ing, breathing person (Grant et al., 2007). Neverthe-

less, research has yet to examine whether and how

beneficiary contact, as a key relational element of

job design, influences followers’ responses to trans-

formational leadership.

I propose that beneficiary contact strengthens the

impact of transformational leadership on follower

performance. Transformational leadership focuses

on linking a vision to core values (Shamir et al.,

1993), and research has shown that protecting and

promoting the well-being of other people is the

most important value to the majority of people in

the majority of the world’s cultures (Schwartz &

Bardi, 2001). When transformational leaders artic-

ulate an inspiring vision, providing beneficiary

contact can enhance the salience and vividness of

the vision’s prosocial impact (Grant, 2007). In this

way, beneficiary contact creates a credible link be-

tween leaders’ words and deeds (Simons, 2002),

enabling employees to see how their organization’s

mission comes to life in benefiting others, which

can motivate employees to work harder and more

effectively (Grant et al., 2007). I test these hypoth-

eses in two field studies—a quasi-experiment and a

survey study. Conducting two studies makes it pos-

sible to replicate effects across both objective mea-

sures and supervisor ratings of job performance, as

well as both temporary, experimentally induced,

and enduring, naturally occurring, differences in

transformational leadership and beneficiary

contact.

This research offers three central contributions to

theory and research on leadership and job design.

First, I introduce beneficiary contact as a novel con-

tingency for the effects of transformational leadership

on follower performance, suggesting that relational

job design can enhance—rather than substitute for—

the effects of transformational leadership on follower

performance. Second, I offer a conceptual and em-

pirical integration of research on leadership and job

design by identifying synergies between inspiring

through words (articulating a compelling vision)

and actions (designing a meaningful job). Third, I

identify a new mechanism for explaining transfor-

mational leadership effects. I show how followers’

perceptions of prosocial impact, rather than of psy-

chological empowerment, play a key role in ac-

counting for the interactive effects of transforma-

tional leadership and beneficiary contact. Together,

these advances extend classic and contemporary

discussions of how leaders’ behaviors and struc-

tural design choices operate as joint determinants

of motivation and performance (e.g., Howell, Dorf-

man, & Kerr, 1986; Yukl, 2008).

TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND

BENEFICIARY CONTACT

My focus is on the effects of transformational

leadership and beneficiary contact on followers’

job performance. Performance is the effectiveness

of followers’ behaviors in advancing organizational

goals (Campbell, 1990). Transformational leader-

ship is typically conceptualized as a collection of

four dimensions of leader behavior: inspirational

motivation, idealized influence, intellectual stimu-

lation, and individualized consideration (Bass,

1985; Burns, 1978). Inspirational motivation in-

volves articulating a compelling vision of the fu-

ture. Idealized influence involves engaging in char-

ismatic actions that earn respect and cultivate

pride, such as discussing important values and be-

liefs, communicating a sense of purpose, and en-

couraging a focus on collective interests. Intellec-

tual stimulation involves challenging followers to

question their assumptions and think differently.

Individualized consideration involves personaliz-

ing interactions with followers by providing rele-

vant mentoring, coaching, and understanding. By

engaging in these transformational behaviors, lead-

2012 459Grant

ers seek to motivate employees to look beyond their

immediate self-interest to contribute to a broader

vision (e.g., Shamir, Zakay, Breinin, & Popper,

1998; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003).

To understand the factors that may strengthen

the capability of transformational leaders to accen-

tuate prosocial impact, I draw on theories of mean-

ing making and job design. Scholars have long

maintained that leaders play a critical role in man-

aging the meaning that followers make of their

work (Podolny, Khurana, & Hill-Popper, 2005; Pratt

& Ashforth, 2003; Shamir et al., 1993; Smircich &

Morgan, 1982; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003).

Transformational leadership, in particular, enables

followers to view their work as more meaningful

(Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Purvanova et al., 2006;

Sparks & Schenk, 2001). Inspirational motivation

highlights an important vision; idealized influence

connects this vision to important shared values;

and individualized consideration personalizes this

connection. As Shamir and colleagues (1993: 578)

explained, “Such leadership is seen as giving

meaningfulness to work by infusing work and or-

ganizations with moral purpose.”

Generally speaking, scholars have recognized

that leaders can influence followers’ perceptions of

meaningfulness through two broad sets of strate-

gies: providing messages that frame and reframe

the meaning of the followers’ work and restructur-

ing responsibilities to change and alter the mean-

ing of the work (Griffin, 1983; Molinsky & Margolis,

2005). Leadership researchers have focused primar-

ily on the former set of strategies, but job design

research has accentuated the substantial impact of

the latter. I seek to integrate the leadership and job

design literatures by examining how designing jobs

to provide beneficiary contact can amplify the ef-

fects of transformational leadership on followers’

performance.

In recent years, job design research has witnessed

a resurgence of attention to the social characteris-

tics of work (Grant & Parker, 2009; Morgeson &

Humphrey, 2006). Instead of viewing jobs merely

as collections of tasks, researchers have increas-

ingly recognized that interpersonal interactions are

critical building blocks of the work that employees

do (Oldham & Hackman, 2010; for reviews and

discussions, see Fried, Levi, and Laurence, 2008;

Grant and Parker, 2009; Kanfer, 2009; Morgeson &

Humphrey, 2008). Although a number of social

characteristics of jobs have been identified, the key

social characteristic that affects meaningfulness is

beneficiary contact—the degree to which employ-

ees have the opportunity to interact with clients,

customers, or others affected by their work (Grant,

2007). Beneficiary contact is a structural character-

istic of jobs that shapes the quality and quantity of

interactions that employees have with recipients of

their products and services (Grant & Parker, 2009;

see also Humphrey, Nahrgang, & Morgeson, 2007).

1

As Kanfer (2009: 122) summarized, “The products

of work motivation and job performance have a

relational component . . . what employees do at

work has import and meaning for others who use

the products produced or benefit in some way from

the employee’s efforts.” For example, beneficiary

contact can involve manufacturing teams interact-

ing with external customers (Kirkman & Rosen,

1999), suppliers interacting with internal custom-

ers (Parker & Axtell, 2001), radiologists having ex-

posure to patients (Turner et al., 2008), or product

developers meeting clients (Sethi & Nichol-

son, 2001).

The Moderating Role of Beneficiary Contact

Research shows that when employees have ben-

eficiary contact, they perceive greater prosocial im-

pact, as they can see and understand the tangible,

meaningful consequences of their contributions for

other people (Grant, 2007). In turn, perceived

prosocial impact is associated with higher effort,

persistence, and job performance (Grant, 2008a;

Grant et al., 2007), as focusing on meaningful con-

sequences for others can encourage employees to

continue working even when they find it unpleas-

ant (De Dreu & Nauta, 2009; Meglino & Korsgaard,

2004). However, research has yet to examine the

interplay of beneficiary contact and leadership.

I propose that beneficiary contact strengthens

the effects of transformational leadership on fol-

lowers’ performance by enhancing followers’ per-

ceptions of prosocial impact. More specifically,

1

Beneficiary contact is conceptually related to, but

distinct from, the two characteristics in the job charac-

teristics model that focus on the outcomes of work: task

identity and task significance (Hackman & Oldham,

1976, 1980). Task identity involves the extent to which

employees see their results; it does not capture the extent

to which employees interact and communicate with the

people who are affected by these results. Research indi-

cates that task identity is distinct from opportunities to

interact with customers, clients, and other recipients

(Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). Task significance focuses

on the consequences of employees’ work for other peo-

ple; beneficiary contact focuses on the extent to which

employees have the opportunity to interact with these

people (Grant, 2007). Studies have shown that benefi-

ciary contact and task significance are empirically dis-

tinct (Grant, 2008b) and operate independently and in-

teractively to influence perceptions and behaviors (Grant

et al., 2007).

460 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

when transformational leaders engage in inspira-

tional motivation and lead by example, employees

are able to identify with an important vision (Pic-

colo & Colquitt, 2006; Shamir et al., 1993), and

beneficiary contact highlights the impact of this

vision on other people. Beneficiary contact enables

employees to see that their contributions to the

vision have meaningful consequences for other

people—that if they work harder and perform more

effectively, living, breathing human beings will be

affected positively (Grant, 2007; Grant et al., 2007).

Two complementary theoretical perspectives illu-

minate the moderating effects of beneficiary con-

tact: the availability heuristic and credibility.

According to the theoretical principles set forth

in formulations of the availability heuristic

(Schwarz, 1998; Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), peo-

ple tend to use vividness and ease of recall as cues

for probability and value. Beneficiary contact

makes the customers or clients who are affected by

a vision more cognitively accessible and emotion-

ally vivid, which will enhance employees’ beliefs

that a transformational leader’s vision is likely to

have a meaningful prosocial impact (see Heath,

Larrick, & Klayman, 1998). This understanding of

prosocial impact is likely to appeal to followers’

core values, as research has shown that benefiting

others and making a social contribution is an im-

portant value across cultures, both at work (Colby,

Sippola, & Phelps, 2001; Ruiz-Quintanilla & Eng-

land, 1996) and in life (Schwartz & Bardi, 2001).

Beneficiary contact can thereby provide employees

with a meaningful face and story to attach to a

transformational leader’s vision, creating vivid im-

agery that makes the vision more tangible (Emrich,

Bower, Feldman, & Garland, 2001).

In the absence of beneficiary contact, employees

may question the credibility of a transformational

leader’s vision, wondering whether it is merely

rhetoric. As Simons (2002: 23) suggested, “Leaders’

exhortations of a new mission or a new focus are

processed by employees as simply a new dogma or

corporate presentation, and are not translated into

action.” To overcome this gap, Kirkpatrick and

Locke (1996: 37) observed, “A leader must go be-

yond simply communicating a vision in order for it

to affect followers.” To achieve influence, it is crit-

ical for leaders to establish credibility (Lam &

Schaubroeck). Employees are most likely to per-

ceive a transformational leader’s vision as credible

when it conveys behavioral integrity—a connection

between words and deeds (Simons, 1999, 2002).

Such integrity can be established by beneficiary

contact, which has the potential to forge a vivid,

credible link between the rhetoric of prosocial im-

pact and the reality of meaningful consequences for

clients, customers, or patients. Beneficiaries can

strengthen the credibility of the leader’s vision by

providing firsthand testimonials from a relatively

neutral, knowledgeable third-party source (Grant &

Hofmann, 2011). Because they are the recipients of

an organization’s products and services, beneficia-

ries are in a unique position to articulate the proso-

cial impact of the organization’s vision (Grant &

Hofmann, 2011).

Thus, I predict that beneficiary contact enhances

the effect of transformational leadership on follow-

ers’ performance by fostering a stronger perception

of prosocial impact. In the language of social infor-

mation processing theory (Salancik & Pfeffer,

1978), transformational leadership involves pro-

viding social cues about the importance of a vision,

and beneficiary contact reinforces these cues by

allowing employees to see the potential prosocial

impact of this vision on clients, customers, or pa-

tients. Beneficiary contact aligns the design of em-

ployees’ jobs with the social cues that they are

receiving from leaders, and such alignment may

reduce uncertainty and ambiguity about the proso-

cial impact of their work (e.g., Griffin, 1983). When

transformational leaders articulate a vision, benefi-

ciary contact brings this vision to life, enabling

followers to perceive integrity in the vision and

recognize the potential for their contributions to

have a meaningful prosocial impact. The resulting

perceptions of prosocial impact, in turn, lead fol-

lowers to work harder and longer, as they perceive

effort as more worthwhile and are able to justify it

even when it is unpleasant (De Dreu & Nauta, 2009;

Grant et al., 2007; Meglino & Korsgaard, 2004).

Beneficiary contact can thus create what Weick

(1984) described as small wins, providing followers

with emotionally resonant glimpses of how small

increases in their performance can realize a leader’s

vision and have a meaningful impact on others. In

summary, I propose a moderated mediation model

in which beneficiary contact strengthens the effect

of transformational leadership on followers’ per-

ceptions of prosocial impact, which in turn contrib-

ute directly to higher performance.

Hypothesis 1. Beneficiary contact strengthens

the relationship between transformational

leadership and followers’ performance.

Hypothesis 2. Followers’ perceptions of proso-

cial impact mediate the moderating effect of

beneficiary contact on the relationship be-

tween transformational leadership and follow-

ers’ performance.

2012 461Grant

Psychological Empowerment as an Alternative

Explanation

An alternative explanation for the moderating

effects of beneficiary contact lies in theories of psy-

chological empowerment. Psychological empower-

ment is thought to involve four psychological

states: meaning (purpose), self-determination

(choice), competence (self-efficacy), and (strategic)

impact (influence on strategic, administrative, or

operating outcomes) (Spreitzer 1995; Thomas and

Velthouse, 1990). Psychological empowerment

provides a parsimonious framework for capturing

the central themes of the psychological states that

are viewed as mediators of the effects of transfor-

mational leadership on follower performance.

Transformational leadership is thought to increase

follower performance by (1) fostering meaning (Pic-

colo & Colquitt, 2006; Purvanova et al., 2006;

Shamir et al., 1993); (2) building competence or

self-efficacy (Gong, Huang, & Farh, 2009; Kirkpat-

rick & Locke, 1996; Liao & Chuang, 2007; Walum-

bwa, Avolio, & Zhu, 2008); (3) encouraging the

pursuit of self-concordant, value-congruent goals,

which are by definition self-determined and auton-

omously chosen (Bono & Judge, 2003); and (4)

strengthening social identification with a group,

department, or organization, which leads employ-

ees to “perceive themselves as important, influen-

tial, effective, and worthwhile in their organiza-

tional units” (Kark, Shamir, & Chen, 2003: 248; see

also Kirkman & Rosen, 1999).

Although these dimensions of empowerment

may mediate any direct relationship that occurs

between transformational leadership and follower

performance, I do not expect that they will be crit-

ical to explaining the moderating effects of benefi-

ciary contact on this relationship. First, meaning

can arise directly through the efforts of transforma-

tional leaders to connect work to personal values

(Bono & Judge, 2003; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Pur-

vanova et al., 2006), independent of any beneficiary

contact that occurs (Rosso, Dekas, & Wrzesniewski,

2010). As Grant (2008a: 119) explains, “The expe-

rience of meaningfulness is a judgment of the gen-

eral value and purpose of the job, with no reference

to the people who it affects.” Thus, beneficiary

contact may be particularly relevant to strengthen-

ing the effect of transformational leadership on em-

ployees’ specific perceptions of prosocial impact,

whereas their more general, abstract perceptions of

meaning may be enhanced by transformational

leadership directly.

Second, with respect to competence, beneficiary

contact provides information about the impact of

followers’ work, not the extent to which they have

completed it effectively (Grant & Gino, 2010).

Third, leaders’ efforts to delegate opportunities and

provide choices influence self-determination

(Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Spreitzer, 1996);

since beneficiary contact is independent of auton-

omy (Grandey & Diamond, 2010), it has little rele-

vance to influencing or reinforcing the opportuni-

ties for choice that transformational leaders

provide. Fourth, although beneficiary contact pro-

vides employees with information about outcomes,

this information focuses on outcomes for the well-

being of clients, customers, and other recipients,

and is thus unlikely to affect the degree to which

transformational leadership enhances perceptions

of impact on strategic, administrative, or operating

outcomes. In summary, although psychological em-

powerment may directly mediate the relationship

between transformational leadership and follower

performance, it is less relevant as a mechanism for

explaining the moderating effect of beneficiary con-

tact on this relationship, which is likely to be

unique to perceived prosocial impact.

Overview of the Present Research

I tested these hypotheses in two studies. Study 1,

a field quasi-experiment with call center employ-

ees, examined whether establishing beneficiary

contact enhanced the effects of a transformational

leadership intervention on performance. Study 2, a

field study in a governmental organization, exam-

ined beneficiary contact as a moderator of the rela-

tionship between employee ratings of transforma-

tional leadership and supervisor ratings of their job

performance. Study 2 also compared perceived

prosocial impact and psychological empowerment

as explanatory mechanisms. In tandem, these stud-

ies facilitate the investigation of the core hypothe-

ses with respect to both temporary, experimentally

induced variations and more enduring, naturally

occurring variations in transformational leadership

and beneficiary contact.

STUDY 1: METHODS

Participants and Design

I conducted this study with new employees at a

privately held company headquartered in the U.S.

Midwest. All 71 new hires participated (response rate

⫽ 100%), and 76.1 percent of them were female. The

company focused on selling educational and market-

ing software to university and nonprofit customers,

and the employees worked at an outbound call cen-

ter. The revenue that employees generated funded job

creation and salaries in another department, but they

462 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

had no contact with the beneficiaries of these jobs

and salaries. The experiment used a 2 (transforma-

tional leadership: yes, no) ⫻ 2 (beneficiary contact:

yes, no) between-subjects factorial design. The em-

ployees were thus arbitrarily divided among four con-

ditions: control, transformational leadership, benefi-

ciary contact, and combined.

Procedures

To start their jobs, all employees were required to

attend a training session and were given the oppor-

tunity to sign up for one of four dates. I learned that

the manager in charge of training was planning to

invite the senior director of the organization to

speak about the company’s mission during one

training session, and he was planning to invite an

“internal customer”—a beneficiary from another

department supported by the employees’ work—to

speak about the importance of their efforts at a

different training session. Otherwise, the employ-

ees had no interaction with the senior director or

the other department. I saw this as an opportunity

for a quasi-experiment and asked the manager if he

could invite both the director and the beneficiary to

the third session. The manager agreed. Employees

in the fourth session, to which no speaker was

invited, served as the control group. Other than the

visits from the director and the beneficiary, the

training sessions were identical. Employees

were not able to self-select into conditions, as they

were not informed in advance that the training

sessions would have different speakers.

For the control group (n ⫽ 26), the manager led

training without a visit from the director or the

beneficiary. For the transformational leadership

group (n ⫽ 15), the director visited the training

session and spoke for 15 minutes. Exemplifying

transformational behaviors (e.g., Bono & Judge,

2003; Locke & Kirkpatrick, 1996; Shamir et al.,

1993), he articulated the company’s vision, ex-

plained why it was meaningful, and communicated

enthusiasm and confidence about employees’ capa-

bilities to achieve it. For the beneficiary contact

group (n ⫽ 12), the beneficiary from a different

department visited the training session for 10 min-

utes. He described how the revenue generated by

the employees had made it possible to create jobs

and fund salaries, including his own. Finally, for

the combined group (n ⫽ 18), both the director and

the beneficiary visited at different points in the

training session and delivered their messages. Both

visitors were blind to the hypotheses.

Measures

Because researcher intervention can compromise

the internal and external validity of experiments

(Argyris, 1975; Cook & Campbell, 1979; Rosenthal,

1994), I did not have contact with the participants

during the study. The manager was already track-

ing data on the employees’ performance, and I was

able to obtain these data for the seven-week period

following the intervention during training. Perfor-

mance was measured on two metrics: number of

sales made and total revenue generated. The em-

ployees were not paid on commission, but they

were eligible for semiannual salary raises based on

their performance on these two metrics. Across the

seven weekly measurement intervals, the measures

of both sales (

␣

⫽ .82) and revenue (

␣

⫽ .72) were

reliable. I also obtained the number of shifts

worked by each employee as a control variable.

After the seven-week performance measurement

period was complete, I gained approval to collect

manipulation check data via an online survey using

a scale anchored at 1, “disagree strongly,” and 7,

“agree strongly.” Of the 71 employees, 38 partici-

pated, for a response rate of 53.5 percent. To assess

the impact of the director’s visit, the survey fea-

tured four items from the Multifactor Leadership

Questionnaire (Avolio, Bass, & Jung, 1999). Em-

ployees evaluated the director on four transforma-

tional leadership items selected to capture the ex-

tent to which inspirational motivation and

idealized influence were reflected in his speech:

“articulates a compelling vision of the future,”

“talks enthusiastically about what needs to be ac-

complished,” “instills pride in me for being asso-

ciated with them,” and “acts in ways that builds my

respect” (

␣

⫽ .79). To assess the impact of the

beneficiary’s visit, the survey featured two items

adapted from Grant’s (2008) beneficiary contact

scale: “My job gives me the opportunity to meet the

people who benefit from my work” and “My job

provides me with contact with the people who

benefit from my work” (

␣

⫽ .75).

STUDY 1: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To evaluate the validity of the interventions, I

conducted 2⫻2 analyses of variance (ANOVAs) on

the manipulation checks. Employees who heard

the director’s speech during training rated him as

significantly more transformational (mean ⫽ 5.01,

s.d. ⫽ 0.95) than those who did not hear his speech

(mean ⫽ 4.17, s.d. ⫽ 1.38), F(1, 37) ⫽ 5.25, p ⬍ .05;

no other effects were significant. In addition, em-

ployees who attended the beneficiary’s visit per-

ceived greater beneficiary contact (mean ⫽ 3.82,

2012 463Grant

s.d. ⫽ 1.39) than those who did not (mean ⫽ 2.94,

s.d. ⫽ 1.22, F[1, 36] ⫽ 3.99, p ⫽ .05); no other

effects were significant. These results indicate sup-

port for the validity of the interventions.

Table 1 displays means and standard deviations

for the key variables by condition. To examine the

effects of the interventions on performance, I began

by conducting 2⫻2 ANOVAs on sales and revenue,

with shifts as a covariate. The results showed a

significant interaction of the transformational lead-

ership and beneficiary contact interventions on

sales (F[1, 66] ⫽ 7.73, p ⬍ .01). There were no

significant main effects of transformational leader-

ship (F[1, 66] ⫽ .01, p ⬎ .93) or beneficiary contact

(F[1, 66] ⫽ .26, p ⬎ .69). The results also showed a

significant interaction of the transformational lead-

ership and beneficiary contact interventions on

revenue (F[1, 66] ⫽ 4.67, p ⫽ .03). There were no

significant main effects of transformational leader-

ship (F[1, 66] ⫽ .00, p ⬎ .99 or beneficiary contact

(F[1, 66] ⫽ .13, p ⬎ .77).

To interpret the significant interactions, which

are graphed in Figures 1 and 2, I conducted simple

effects tests within each level of beneficiary con-

tact. When beneficiary contact was present, the

transformational leadership intervention had a sig-

nificant, positive effect on sales (F[1, 67] ⫽ 4.25,

p ⫽ .04 [p

one-tailed

⬍ .02]) and a marginal effect on

revenue (F[1, 67] ⫽ 2.91, p ⫽ .09 [p

one-tailed

⬍ .05]).

When beneficiary contact was absent, on the other

hand, the transformational leadership intervention

had no effect on sales (F[1, 67] ⫽ .01, p ⬎ .90) or

revenue (F[1, 67] ⫽ .43, p ⬎ .51). These results

provide initial evidence in support of the hypoth-

esis that beneficiary contact strengthens the effects

of transformational leadership on followers’

performance.

At the same time, these findings are subject to

several important limitations. First, the fact that the

data were collected within a single job raises ques-

tions about the generalizability of the findings to

other jobs and occupations. Second, the transfor-

mational leadership and beneficiary contact inter-

ventions consisted of short, one-time visits and

speeches. However, among working employees, a

single speech alone may be insufficient to increase

performance. In practice, transformational leader-

ship is often an everyday, repeated behavioral act

(e.g., Purvanova & Bono, 2009), and beneficiary

contact is often a relatively enduring aspect of a job

design (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Stone &

Gueutal, 1985). This may help to explain why there

were no main effects of transformational leadership

or beneficiary contact.

Third, the quasi-experimental design is vulnera-

ble to validity and implementation threats (Cook &

Campbell, 1979). Although the arbitrary assign-

ment procedure prevented participants from self-

selecting into conditions, it is not possible to rule

out history threats to validity: other events may

have occurred along with the experimental treat-

ment and driven the results. Furthermore, multiple

treatment interference is a possibility: it may be the

case that simply hearing about the importance of

the work from two different sources, rather than the

specific transformational behavior by the leader

and the interaction with the beneficiary, enhanced

the credibility of the message. In terms of imple-

mentation threats, it is possible that employees

shared information about their experiences during

training, and those who did not receive both the

leader and beneficiary speeches experienced re-

sentful demoralization. Fourth, I was not able to

obtain survey data on mediating mechanisms from

participating employees. This made it difficult to

understand the underlying processes responsible

for the findings.

STUDY 2: METHODS

This study was designed to constructively repli-

cate and extend the findings of Study 1 by address-

TABLE 1

Study 1: Means and Standard Deviations by Condition

a

Condition

Number

of Sales

Total

Revenue

Sales

per Shift

Revenue

per Shift

Control (n ⫽ 26) 46.23 $3,738.73 1.65 $138.61

(39.30) (3,407.49) (0.84) (75.71)

Transformational leadership

(n ⫽ 15)

151.80 $12,129.04 1.55 $119.49

(102.34) (10,284.34) (0.56) (58.86)

Beneficiary contact (n ⫽ 12) 77.67 $5,952.83 1.67 $131.94)

(50.68) (4,081.64) (0.74) (77.67)

Combined transformational leadership

and beneficiary contact (n ⫽ 18)

271.22 $21,376.58 2.11) $166.97

(92.15) (6,806.03) (0.44) (35.73)

a

Standard deviations are in parentheses.

464 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

ing the aforementioned limitations. First, to in-

crease generalizability, I collected data from

employees in a wide range of jobs working for

different leaders. Second, to directly examine more

enduring leadership and job experiences, I col-

lected data on naturally occurring differences be-

tween employees in perceptions of transforma-

tional leadership and beneficiary contact. Third, to

overcome the vulnerability of quasi-experimental

designs to the aforementioned validity and imple-

mentation threats, I collected multisource survey

data. Fourth, to examine mediating mechanisms, I

collected data from employees on perceived proso-

cial impact and psychological empowerment.

Participants and Procedures

I collected data from 329 employees and their

direct supervisors in a large U.S. government or-

ganization. The human resources director identi-

fied 1,197 employees who had unique supervisors,

and I sent them invitations to participate in a study

of work attitudes. I received completed online sur-

veys from 418 employees, for a response rate of

34.9 percent. I sent requests to their direct supervi-

sors to complete a short online performance evalu-

ation and received completed surveys from 344

supervisors, for a response rate of 82.3 percent. I

was able to match 329 of the employee and super-

visor surveys; these matched surveys constituted

the final sample. Female employees comprised

63.5% of the sample; average job tenure was

6.3 years (s.d. ⫽ 7.4), and average age was

37.2 years (s.d. ⫽ 13.0). These respondents worked

in more than 20 different jobs, including engineer-

ing and manufacturing, customer service, financial

analysis, information technology, quality assur-

FIGURE 1

Study 1 Results for Sales per Shift

FIGURE 2

Study 1 Results for Revenue per Shift

2012 465Grant

ance, and legal and contracting services. Their su-

pervisors were 60.8 percent female, with an average

job tenure of 9.0 years (s.d. ⫽ 8.3) and an average

age of 45.3 years (s.d. ⫽ 9.7).

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, all items used a

scale anchored at 1, “disagree strongly,” and 7,

“agree strongly.” Supervisors provided ratings of

employees’ job performance, and employees pro-

vided ratings of transformational leadership, as

well as self-reports of perceived prosocial im-

pact, psychological empowerment, and several

control variables.

Performance. To rate employees’ job perfor-

mance, the supervisors completed the five-item

scale developed by Ashford and Black (1996). They

were asked to evaluate employees’ performance on

a nine-point scale in percentiles, ranging from the

bottom 10 percent to the top 10 percent. The items

included “overall performance,” “achievement of

work goals,” and “quality of performance”

(

␣

⫽ .96).

Transformational leadership. Employees com-

pleted the 20-item Multifactor Leadership Ques-

tionnaire (Avolio et al., 1999) with reference to

their direct supervisor (

␣

⫽ .82). Sample items in-

clude “articulates a compelling vision of the fu-

ture” (inspirational motivation), “specifies the im-

portance of having a strong sense of purpose”

(idealized influence), “seeks differing perspectives

when solving problems” (intellectual stimulation),

and “spends time teaching and coaching” (individ-

ualized consideration).

Beneficiary contact. Since the intervention in

Study 1 consisted of a very specific interaction

with a single beneficiary, it was important to rep-

licate the results by using a measure of more en-

during and naturalistic beneficiary contact. Em-

ployees completed four items adapted from

measures developed by Morgeson and Humphrey

(2006): “My job involves a great deal of interaction

with the people who benefit from my work,” “On

the job, I frequently communicate with the people

affected by my work,” “The job requires spending a

great deal of time with the people who benefit from

my work,” and “The job involves interaction with

the people affected by my work” (

␣

⫽ .92). These

items were based on Morgeson and Humphrey’s

(2006) measure of interaction outside a respon-

dent’s organization, but the referent was beneficia-

ries—as specified by Grant (2008b)—rather than

any people outside the organization. In pilot data,

the most commonly listed beneficiaries were cus-

tomers, citizens, and the community.

Perceived prosocial impact. Employees com-

pleted the three-item scale developed by Grant

(2008a), which includes items such as “I feel that

my work makes a positive difference in other peo-

ple’s lives” (

␣

⫽ .81).

Psychological empowerment. Employees com-

pleted Spreitzer’s (1995) 12-item scale (

␣

⫽ .90),

which includes 3 items each for meaning (e.g.,

“The work I do is meaningful to me”;

␣

⫽ .81),

competence (e.g., “I have mastered the skills nec-

essary for my job”;

␣

⫽ .89), self-determination

(e.g., “I have considerable opportunity for indepen-

dence and freedom in how I do my job”;

␣

⫽ .86),

and (strategic) impact (e.g., “My impact on what

happens in my department is large”;

␣

⫽ .93).

Control variables. Since the quality of the rela-

tionship between employees and supervisors af-

fects the ratings that supervisors give (e.g., Judge &

Ferris, 1993), I controlled for relationship quality to

minimize reporting biases. Employees evaluated

their relationships with their supervisors on three

items adapted from Ashford, Rothbard, Piderit, and

Dutton’s (1998) relationship quality scale, includ-

ing “trusting” and “close” (

␣

⫽ .86). In addition, to

establish the incremental validity of the moderat-

ing role of beneficiary contact, I controlled for sev-

eral related job characteristics, using Morgeson and

Humphrey’s (2006) scales to measure task identity

(e.g., “The job is arranged so that I can do an entire

piece of work from beginning to end”;

␣

⫽ .84), task

significance (e.g., “The results of my work are

likely to significantly affect the lives of other peo-

ple”;

␣

⫽ .87), interpersonal feedback (e.g., “I re-

ceive feedback on my performance from other peo-

ple in my organization”;

␣

⫽ .91), and friendship

opportunities (e.g., “I have the opportunity to de-

velop close friendships in my job”;

␣

⫽ .89). I

selected task identity and task significance because

these two characteristics relate to the outcomes of

an individual’s job, as discussed earlier, and inter-

personal feedback and friendship opportunities be-

cause these are two other social job characteristics

that capture key aspects of employees’ work-related

interactions (Grant & Parker, 2009; Morgeson &

Humphrey, 2006).

STUDY 2: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for

the focal variables appear in Table 2. To assess the

factor structures of the performance, leadership, job

design, and perceptual variables, I conducted a

confirmatory factor analysis using EQS software

version 6.1 with maximum-likelihood estimation

procedures (e.g., Bentler & Dudgeon, 1996; Kline,

1998). In keeping with past research (e.g., Piccolo &

466 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

Colquitt, 2006), I constructed one parcel for each of

the four dimensions of transformational leadership.

I specified a 13-factor solution, with distinct, freely

correlated factors for supervisor performance ratings,

transformational leadership, beneficiary contact,

relationship quality, task identity, task signifi-

cance, interpersonal feedback, friendship opportu-

nities, perceived prosocial impact, and the mean-

ing, competence, self-determination, and strategic

impact dimensions of psychological empower-

ment. This 13-factor solution achieved good fit

with the data (

2

[824] ⫽ 1,679.75, CFI ⫽ .94,

SRMR ⫽ .05). All factor loadings were statistically

significant and ranged from .73 to .97 for supervisor

performance ratings, .91 to .96 for transformational

leadership, .77 to .93 for beneficiary contact, .77 to

.86 for relationship quality, .66 to .91 for task iden-

tity, .80 to .83 for task significance, .81 to .91 for

interpersonal feedback, .76 to .95 for friendship

opportunities, .62 to .88 for perceived prosocial

impact, .88 to .97 for meaning, .80 to .94 for com-

petence, .72 to .86 for self-determination, and .88 to

.97 for strategic impact. Chi-square difference tests

showed that all alternative nested models achieved

significantly poorer fit, and constraining correla-

tions between each pair of factors to 1.0 also re-

duced model fit significantly. These analyses sup-

ported the expected factor structure of the variables.

I began testing the hypotheses using hierarchical

ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses,

following the moderated regression procedures rec-

ommended by Aiken and West (1991). I standard-

ized the focal variables, multiplied them to create

interaction terms, and predicted supervisor perfor-

mance ratings. I entered the control variables,

transformational leadership, and beneficiary con-

tact in step 1, the interactions of transformational

leadership with the control variables in step 2, and

the interaction of transformational leadership and

beneficiary contact in step 3. The results, which are

displayed in Table 3, indicated a statistically sig-

nificant interaction between transformational lead-

ership and beneficiary contact in predicting super-

visor performance ratings.

To interpret the form of this interaction, I plotted

the simple slopes at one standard deviation above

and below the mean of beneficiary contact (Aiken &

West, 1991). As displayed in Figure 3, transforma-

tional leadership appeared to be positively related

to supervisor performance ratings when beneficiary

contact was high but not when it was low. To test

this interpretation statistically, I compared each of

the simple slopes to zero. When beneficiary contact

was high, the relationship between transforma-

tional leadership and performance was positive

and statistically significant (b ⫽ .48, s.e. ⫽ .12,

⫽ .31, p ⬍ .001). In contrast, when beneficiary

contact was low, the relationship between transfor-

mational leadership and performance did not differ

significantly from zero (b ⫽ .10, s.e. ⫽ .12,

⫽ .06,

p ⫽ .40). These results show that beneficiary con-

tact strengthened the relationship between trans-

formational leadership and performance. In sup-

plementary analyses, none of the other job

characteristics interacted significantly with trans-

formational leadership, supporting the uniqueness

of the moderating role of beneficiary contact.

To examine the role of perceived prosocial im-

pact, I followed the moderated mediation proce-

dures specified by Edwards and Lambert (2007).

The hypotheses focused on first-stage moderation:

beneficiary contact strengthens the relationship be-

tween transformational leadership and perceived

prosocial impact, and perceived prosocial impact

TABLE 2

Study 2: Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

a

Variable Mean s.d. 1234567891011121314

1. Supervisor performance ratings 7.64 1.55 (.96)

2. Transformational leadership 4.54 1.28 .18 (.82)

3. Beneficiary contact 4.56 1.57 .04 .23 (.92)

4. Perceived prosocial impact 5.18 1.27 .22 .53 .30 (.81)

5. Psychological empowerment 5.54 0.91 .26 .54 .22 .62 (.90)

6. Empowerment: Meaning 5.44 1.23 .14 .44 .18 .61 .78 (.81)

7. Empowerment: Competence 6.04 0.88 .28 .20 .11 .37 .64 .34 (.89)

8. Empowerment: Self-determination 5.38 1.14 .18 .26 .21 .27 .71 .33 .39 (.82)

9. Empowerment: Strategic impact 5.23 1.46 .20 .64 .18 .56 .84 .56 .38 .45 (.95)

10. Relationship quality 5.38 1.23 .10 .51 .22 .42 .48 .43 .21 .35 .45 (.86)

11. Task identity 5.26 1.31 .09 .35 .22 .36 .48 .37 .32 .47 .40 .47 (.84)

12. Task significance 4.74 1.25 .07 .36 .36 .62 .44 .45 .22 .32 .33 .32 .32 (.87)

13. Interpersonal feedback 4.55 1.47 .11 .33 .30 .29 .36 .32 .14 .30 .28 .44 .36 .35 (.91)

14. Friendship opportunities 5.61 1.07 .16 .29 .30 .26 .36 .22 .29 .40 .28 .50 .33 .29 .38 (.89)

a

Coefficient alphas appear on the diagonal in parentheses. All r ⬎ .10 are significant at p ⬍ .05; all r ⬎ .14, p ⬍ .01; all r ⬎ .18, p ⬍ .001.

2012 467Grant

then contributes directly to performance. I began by

conducting moderated regression analyses predict-

ing perceived prosocial impact (see Table 4, left

column). There was a statistically significant inter-

action between transformational leadership and

beneficiary contact in predicting perceived proso-

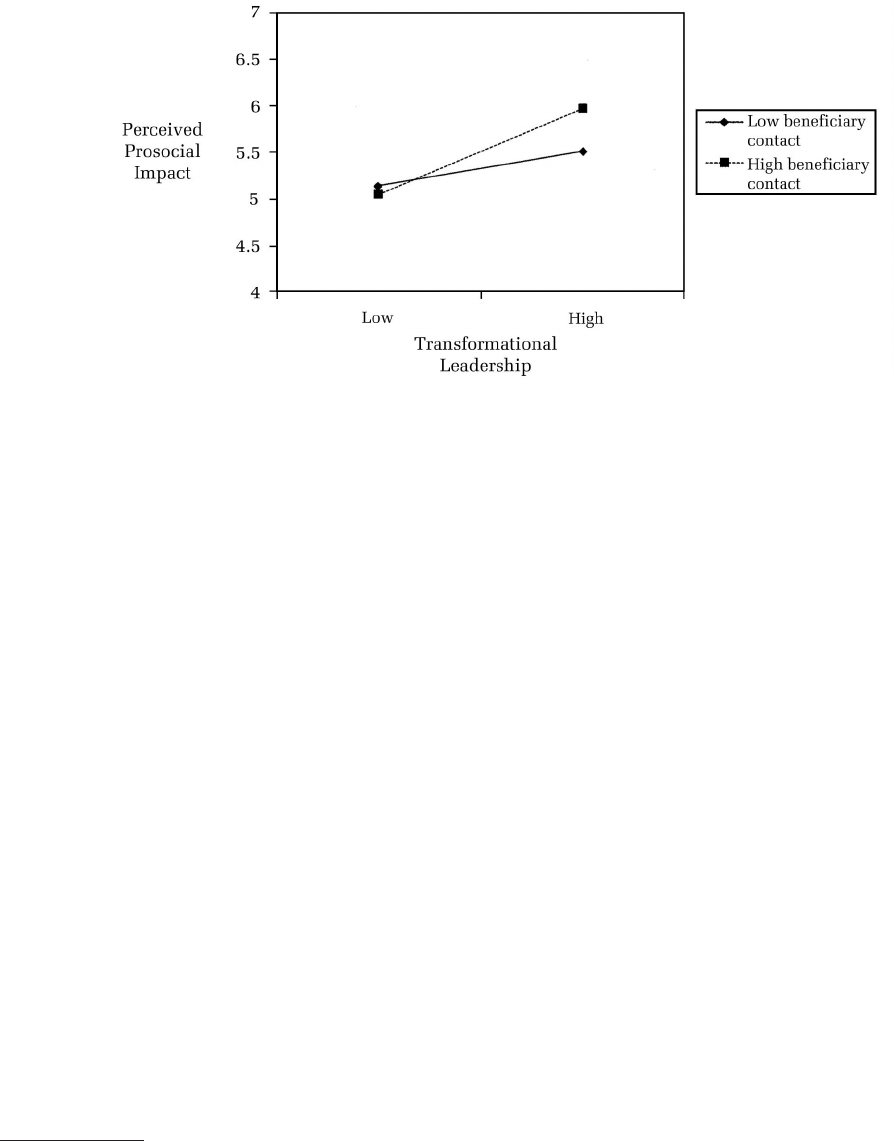

cial impact. The simple slopes (Figure 4) suggest

that the relationship between transformational

leadership and perceived prosocial impact was

more strongly positive under high than low bene-

ficiary contact. Comparing the slopes to zero sup-

ported this interpretation: the relationship between

transformational leadership and performance was

positive and statistically significant when benefi-

ciary contact was high (b ⫽ .72, s.e. ⫽ .08,

⫽ .57,

p ⬍ .001) and less positive but still statistically

significant when beneficiary contact was low

(b ⫽ .52, s.e. ⫽ .08,

⫽ .41, p ⬍ .001).

TABLE 3

Study 2: Moderated Regression Analyses Predicting Supervisor Performance Ratings

a

Variables

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

b s.e.

tbs.e.

tbs.e.

t

Transformational leadership .27 .10 .18 2.67** .28 .10 .18 2.66** .28 .10 .18 2.74**

Beneficiary contact –.07 .09 –.04 –0.71 –.07 .10 –.05 –0.74 –.02 .10 –.01 –0.20

Relationship quality –.12 .12 –.08 –1.08 –.07 .13 –.04 –0.50 –.08 .13 –.05 –0.64

Task identity .02 .10 .01 0.19 .00 .11 .00 –0.03 .04 .11 .02 0.33

Task significance –.02 .10 –.01 –.17 –.02 .10 –.01 –0.15 –.02 .10 –.01 –0.19

Interpersonal feedback .06 .10 .04 0.59 .04 .10 .03 0.39 .02 .10 .01 0.19

Friendship opportunities .23 .10 .15 2.30* .25 .11 .16 2.14* .23 .11 .15 2.01*

Transformational leadership ⫻ relationship quality .16 .11 .12 1.45 .16 .11 .12 1.46

Transformational leadership ⫻ task identity –.06 .10 –.04 –0.59 –.09 .10 –.06 –0.85

Transformational leadership ⫻ task significance .03 .09 .02 0.33 –.02 .09 –.01 –0.17

Transformational leadership ⫻ interpersonal feedback –.13 .11 –.09 –1.22 –.17 .11 –.12 –1.61

Transformational leadership ⫻ friendship opportunities –.01 .10 –.01 –0.09 –.07 .10 –.05 –0.65

Transformational leadership ⫻ beneficiary contact .27 .09 .19 3.07**

R

2

.05* .06 .09**

F( df) 2.51 (7, 321) 0.61 (5, 316) 9.40 (1, 315)

⌬R

2

.02 .03**

a

Theoretically, beneficiary contact should be most likely to moderate the effects of inspirational motivation and the leading by example

aspects of idealized influence. However, the results were consistent across each facet of transformational leadership, likely because of their

high correlations (r

mean

⫽ .86, r

minimum

⫽ .83, r

maximum

⫽ .89).

b

Values shown in bold reflect hypothesized results.

* p ⬍ .05

** p ⬍ .01

FIGURE 3

Study 2 Simple Slopes for Supervisor Performance Ratings

468 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

TABLE 4

Study 2: Moderated Mediation Analyses

a

Variables

DV: Perceived Prosocial Impact DV: Psychological Empowerment DV: Supervisor Performance Ratings

Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2 Step 1 Step 2

b s.e.

tbs.e.

tbs.e.

tbs.e.

tbs.e.

tbs.e.

t

Transformational leadership .38 .06 .30 6.34*** .37 .06 .29 6.24*** .28 .05 .31 6.13*** .28 .05 .30 6.04*** .26 .10 .17 2.57* .10 .11 .07 0.95

Beneficiary contact .07 .06 .06 1.27 .10 .06 .08 1.86 –.03 .04 –.03 –0.59 –.01 .04 –.01 –0.25 –.01 .10 –.01 –0.13 –.04 .09 –.02 –0.37

Relationship quality .14 .07 .11 2.05* .15 .07 .12 2.24* .09 .05 .10 1.72 .09 .05 .10 1.82 –.10 .12 –.06 –0.83 –.16 .11 –.10 –1.40

Task identity .11 .06 .09 1.85 .13 .06 .11 2.31* .21 .04 .23 4.77*** .22 .05 .25 4.99*** .06 .10 .04 0.61 –.04 .10 –.02 –0.37

Task significance .58 .06 .46 1.06 .59 .06 .47 1.39 .17 .04 .19 3.97*** .18 .04 .20 4.05*** –.02 .10 –.02 –0.25 –.19 .11 –.12 –1.71

Interpersonal feedback ⫺.07 .06 –.06 -1.20 –.08 .06 –.06 –1.32 .04 .05 .04 0.81 .03 .05 .04 0.72 .02 .10 .01 0.22 .04 .10 .03 0.39

Friendship opportunities ⫺.06 .06 –.04 -0.90 –.06 .06 –.05 –1.00 .08 .05 .09 1.70 .08 .05 .09 1.70 .26 .10 .16 2.52* .24 .10 .15 2.31*

Transformational leadership ⫻

beneficiary contact

.16 .05 .14 3.48** .06 .04 .08 1.83 .19 .08 .13 2.39* .14 .08 .10 1.79

Psychological empowerment .30 .13 .18 2.25*

Perceived prosocial impact .20 .10 .17 2.00

R

2

.51*** .53*** .44*** .45*** .07** .11***

F(df) 47.66 (7, 320) 12.11 (1, 319) 37.07 (7, 321) 3.35 (1, 320) 3.15 (8, 319) 7.02 (1, 319)

⌬R

2

.02** .01 .04**

a

The results did not change substantively with inclusion of the interactions between transformational leadership and the control variables. In addition, in analysis of the dimensions

of psychological empowerment separately rather than as a composite, the moderated mediation model was supported for perceived prosocial impact, but not for any of the dimensions

of psychological empowerment. This is not surprising in light of evidence that the dimensions tend to be highly correlated and share similar antecedents and outcomes (Seibert, Wang,

& Courtright, 2011).

b

Values shown in bold reflect hypothesized results.

* p ⬍ .05,

** p ⬍ .01

*** p ⬍ .001

Next, I tested whether perceived prosocial im-

pact predicted supervisor performance ratings

when transformational leadership, beneficiary con-

tact, and their interaction were controlled. I con-

ducted these analyses while controlling for psycho-

logical empowerment (Table 4, right column). In

both analyses, perceived prosocial impact was a

significant predictor even after I had controlled for

these variables, and the coefficient on the interac-

tion term decreased below statistical significance.

To examine whether this was a significant de-

crease, I used bootstrap procedures to construct

95% bias-corrected confidence intervals around

the indirect effects at both levels of beneficiary

contact (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). The confidence

interval for the indirect effect of transformational

leadership on supervisor performance ratings

through perceived prosocial impact excluded zero

for both high beneficiary contact (.05, .29) and low

beneficiary contact (.01, .15), indicating that per-

ceived prosocial impact mediated the relationship

between transformational leadership and follower

performance at both levels of beneficiary contact.

2

In addition, the confidence interval for the differ-

ence between these two indirect effects excluded

zero (.02, .22), indicating that the indirect effect

was significantly stronger under high rather than

low beneficiary contact. These results support the

moderated mediation model, showing that per-

ceived prosocial impact is an explanatory mecha-

nism even after one controls for psychological

empowerment.

Psychological empowerment independently pre-

dicted supervisor performance ratings (Table 4,

right column), but beneficiary contact did not mod-

erate the relationship of transformational leader-

ship with psychological empowerment (Table 4,

middle column). These findings support the pre-

diction that perceived prosocial impact, rather than

psychological empowerment, is a key mechanism

through which beneficiary contact strengthens the

relationship between transformational leadership

and follower performance.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

These studies provide convergent evidence that

the relationship between transformational leader-

ship and follower performance is stronger under

beneficiary contact. In the first study, a transforma-

tional leadership intervention enhanced sales and

revenue, but only when employees had contact

with a beneficiary. In the second study, the positive

association between transformational leadership

and supervisor ratings of follower performance was

stronger under beneficiary contact, and followers’

perceptions of prosocial impact mediated this in-

teractive relationship.

Theoretical Contributions

This research advances knowledge about leader-

ship, job design, and meaning. The primary contri-

bution lies in introducing beneficiary contact as an

important moderator of the impact of transforma-

2

Under high beneficiary contact, the confidence inter

-

vals excluded zero for both the direct effects (.03, .58)

and the total effects (.20, .73). Under low beneficiary

contact, on the other hand, the confidence intervals in-

cluded zero for both the direct effects (–.26, .37) and the

total effects (–.21, .42).

FIGURE 4

Study 2 Simple Slopes for Perceived Prosocial Impact

470 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

tional leadership on follower performance. Al-

though evidence has accumulated that both trans-

formational leadership and beneficiary contact can

motivate employees to perform more effectively,

little theory and research have examined the inter-

play between these two approaches to imbuing

work with meaning. In identifying beneficiary con-

tact as an enhancer of the effects of transforma-

tional leadership, my theoretical perspective and

empirical findings represent a departure from tra-

ditional approaches to understanding the interac-

tions of leadership and job design. In classic re-

search, the assumption has been that job design is a

substitute for leadership: well-designed tasks com-

pensate for the absence of leadership behaviors by

providing employees with the intrinsic motivation

and direction necessary to complete their work ef-

fectively regardless of vision and inspiration from

leaders (Kerr & Jermier, 1978). Some studies have

supported this perspective (Dionne, Yammarino,

Atwater, & James, 2002; Keller, 2006; cf. Podsakoff,

MacKenzie, & Bommer, 1996), but this research has

focused on task characteristics, giving little theoret-

ical and empirical attention to the social character-

istics of jobs. From a leadership substitutes per-

spective, one might expect beneficiary contact to

serve a compensatory function, fostering percep-

tions of prosocial impact when transformational

leadership is lacking. However, my research sup-

ports the opposite functional form of the interac-

tion. These studies thereby open up a new direc-

tion for leadership research, suggesting that

although task characteristics may be substitutes for

leadership, social characteristics of jobs may be

more likely to operate as enhancers.

The studies also highlight the potential for re-

thinking and broadening existing knowledge about

the behaviors of transformational leaders. As it is

traditionally studied, the inspirational motivation

dimension of transformational leadership focuses

on the use of language and rhetoric to instill enthu-

siasm, optimism, confidence, and purpose in fol-

lowers (e.g., Avolio et al., 1999; Bass, 1985; Emrich

et al., 2001; Shamir et al., 1993, 1998). My research

suggests that transformational leadership may also

involve modifying the structural designs of follow-

ers’ jobs. This evidence points to a novel interpre-

tation of recent studies linking transformational

leadership to perceptions of job enrichment and

meaningfulness (Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Pur-

vanova et al., 2006). Whereas these researchers

have assumed that transformational leaders influ-

ence employees’ job perceptions and performance

through the rhetoric that they use, my research

indicates that transformational leaders can also

achieve such influence through objectively altering

the design of employees’ jobs to create greater in-

teraction with beneficiaries. My studies suggest

that rhetoric and design in combination, rather

than one or the other alone, may maximize the

extent to which followers perceive their work as

having a prosocial impact and perform effectively

as a result. As such, my research takes a step toward

answering recent calls to better understand the inter-

play of job design and leadership (Piccolo et al., 2010)

and draws attention to relational job design as a

moderator of transformational leadership effects,

complementing previously studied contingencies

such as environmental uncertainty, cultural values,

social and physical distance, and follower charac-

teristics (for reviews, see Bass & Riggio, 2006; Avo-

lio, Walumbwa, & Weber, 2009).

Accordingly, my findings invite scholars to con-

sider the possibility that transformational leaders

can inspire employees not only through the words

that they articulate to link work to an important

purpose, but also through the actions that they

undertake to redesign this work to strengthen con-

nections to this purpose. Recent research shows

that it is difficult for leaders to create perceptions of

prosocial impact through their own words; mes-

sages highlighting prosocial impact are more com-

pelling when delivered directly by beneficiaries

(Grant & Hofmann, 2011). Should connecting em-

ployees with beneficiaries outside their work

groups be viewed as a transformational leadership

behavior? If so, it may be fruitful to conceive of

transformational leadership as a form of boundary

management in which leaders close the gap be-

tween employees and beneficiaries, serving as link-

ing pins (Katz & Kahn, 1966) to bridge “structural

holes” between employees and beneficiaries (Burt,

1997; Obstfeld, 2005).

My research also identifies perceived prosocial

impact as a new mechanism for explaining trans-

formational leadership effects. As discussed previ-

ously, existing research has focused on how trans-

formational leadership operates through meaning,

self-concordance, competence or self-efficacy, and

social identification. These mechanisms focus on

employees’ perceptions of their work, their own

capabilities, and their relationships with leaders

and work group members. Perceived prosocial im-

pact differs from these mechanisms in that it pri-

marily emphasizes employees’ perceptions of their

relationships with beneficiaries outside their work

groups. My research thus introduces a fresh under-

standing of how transformational leadership can

shape performance by influencing how employees

judge their relationships with the recipients of their

products and services, not only their relationships

with leaders and employees inside their work

2012 471Grant

groups. This theoretical perspective and empirical

evidence widen the relational scope of transforma-

tional leadership effects.

Finally, my research extends current knowledge

about the psychological and performance effects of

relational job design, which scholars have identi-

fied as a productive direction for future research

(Grant & Parker, 2009; Kanfer, 2009; Morgeson &

Humphrey, 2008; Oldham & Hackman, 2010). Pre-

vious studies have shown how beneficiary contact,

independently and in conjunction with supporting

task characteristics, can enhance attitudes and per-

formance (Grant, 2007; Humphrey et al., 2007). Lit-

tle research, however, has addressed how factors

other than job design interact with beneficiary con-

tact to affect employees’ psychological and behav-

ioral reactions. My studies provide what may be the

first evidence that beneficiary contact interacts

with leadership to influence perceptions of proso-

cial impact and performance. These findings sug-

gest that to develop a comprehensive understand-

ing of the impact of relational job design on

employees, it is important to examine leadership

behaviors in tandem with job characteristics.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Practical

Implications

These studies are subject to a number of limita-

tions that point toward avenues for future research.

One inconsistency between the two studies con-

cerned the effect of transformational leadership on

performance under low beneficiary contact; this

effect was insignificant in both studies but showed

a negative trend (Study 1) versus a positive trend

(Study 2). Future research is necessary to compare

a number of possible explanations for this diver-

gence, including differences in the focus on em-

ployees in for-profit versus governmental organiza-

tions, objective versus supervisor ratings of

performance, and temporary versus enduring lead-

ership behaviors and job characteristics. It may be

the case that small doses of transformational lead-

ership depend heavily on beneficiary contact to

make the consequences of a leader’s vision for

other people tangible, whereas when transforma-

tional leadership is a salient component of every-

day work life, beneficiary contact has incremental

value but is not strictly necessary. Alternatively,

the employees in the Study 2 sample who reported

low beneficiary contact may still have had suffi-

cient interaction with customers and clients that

they were able to vividly understand and envision

the impact of their organization’s work. As an

anonymous reviewer for this article noted, these

two studies do not rule out the possibility that job

design and organizational culture can be a substi-

tute for transformational leadership. For some jobs,

organizations, and occupations, the work may be so

deeply imbued with ideological significance that

its prosocial impact is vivid and chronically salient

to employees. In these situations, it may not be

necessary or beneficial for leaders to provide addi-

tional inspiration or to redesign jobs.

On a related note, in both studies, beneficiary

contact was not independently associated with

higher performance. This raises important ques-

tions about whether the effects of beneficiary con-

tact vary as a function of its structure and content

(Grandey & Diamond, 2010; Grant & Parker, 2009).

For example, a beneficiary’s need, similarity, emo-

tional expressions, responsibility, charisma, au-

thenticity, and attractiveness may be important

contingencies that affect employees’ reactions (e.g.,

Batson & Shaw, 1991; Grant et al., 2007; Small &

Verrochi, 2009), and I did not measure or manipu-

late these potential contingencies in the present

studies. The match or fit between a beneficiary and

a leader’s vision is also likely to be important. More

generally, beneficiary contact is only one of multi-

ple social characteristics of work, and it will be

valuable to gain a deeper understanding of the po-

tential moderating effects of other social character-

istics, such as task interdependence, social support

and undermining, requirements for harm doing,

and accountability (Grant & Parker, 2009; Hum-

phrey et al., 2007).

In Study 1, the results may have been partially

influenced by the fact that two different speakers

reinforced the message. Although Study 2 offset

this limitation by using employees’ ratings of on-

going levels of transformational leadership and

beneficiary contact, future experimental studies

should independently vary the number of messages

and their source. Another limitation is that the

studies provide little insight into the duration of

the interactive performance effects of transforma-

tional leadership and beneficiary contact. The first

study was limited to seven weeks of performance

measurement, and the second study included only

cross-sectional data. Since the effects of motiva-

tional interventions often fade over time (e.g., Mc-

Natt & Judge, 2004), it will be critical to build, test,

and refine theory about how beneficiary contact

influences the sustainability of performance

changes over time, as well as to test the underlying

availability and credibility mechanisms implied in

the theory development.

I was unable to track differences among the di-

mensions of transformational leadership (cf.

Shamir et al., 1998) and in the types of social cues

provided (Zalesny & Ford, 1990). These shortcom-

472 AprilAcademy of Management Journal

ings raise unanswered questions about the specific

behaviors of transformational leaders that are en-

hanced by beneficiary contact. In addition, future

research should manipulate and measure other

leadership constructs—such as leader-member ex-

change, empowering leadership, and authentic

leadership (for a review, see Avolio et al.

[2009])—to address the extent to which the moder-

ating role of beneficiary contact is unique to trans-

formational leadership. Evaluating Study 2 in iso-

lation, it is difficult to ascertain whether the effects

are driven by the leader’s behavior, the follower’s

perception of the leader, or a combination of the

two. This limitation is partially offset by Study 1,

which shows that objective leadership behaviors

interact with beneficiary contact to influence per-

formance, but future research should include mul-

tiple followers per leader to demonstrate consensus

in follower ratings. This may yield greater discrim-

inant validity between facets of transformational

leadership and inform whether the moderating ef-

fects of beneficiary contact apply primarily to in-

spirational motivation and idealized influence.

These limitations notwithstanding, the present

research shows how beneficiary contact can en-

hance the performance effects of transformational

leadership. Transformational leaders may bring

prosocial visions to life by establishing contact be-

tween employees and beneficiaries (see Grant,

2011). As Medtronic’s former CEO Bill George (in a

2010 personal communication) reflected:

Medtronic’s mission is not fulfilled until the person

is restored to full life and health, even with chronic

and intractable diseases. They need to remember

that when they get frustrated, they’re here to restore

people to full life and health. If I’m making semi-

conductors, how do I get to see the impact on pa-

tients? If I’m doing software development, if there

was a glitch in a defibrillator, people could be

harmed or killed. . . . Medtronic covers two out of

every three surgeries with someone in the room—

salespeople, technicians, clinical specialists. . . . It’s

very important that they get out there and see pro-

cedures. . . . You get to see the patients firsthand . . .

it’s a way of communicating what we’re all about.

REFERENCES

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. 1991. Multiple regression:

Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage.

Argyris, C. 1975. Dangers in applying results from exper-

imental social psychology. American Psychologist,

30: 469–485.

Ashford, S. J., & Black, J. S. 1996. Proactivity during

organizational entry: Antecedents, tactics, and out-

comes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81: 199 –

214.

Ashford, S. J., Rothbard, N. P., Piderit, S. K., & Dutton,

J. E. 1998. Out on a limb: The role of context and

impression management in spelling gender equity

issues. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43: 23–

57.

Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. 1999. Re-examining

the components of transformational and transac-

tional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership

Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational and Or-

ganizational Psychology, 72: 441–462.

Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. 2009.

Leadership: Current theories, research, and future

directions. In Annual review of psychology, vol. 60:

421–449. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.

Barling, J., Weber, T., & Kelloway, E. K. 1996. Effects of

transformational leadership training on attitudinal

and financial outcomes: A field experiment. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 81: 827– 832.

Bass, B. M. 1985. Leadership and performance beyond

expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. 2006. Transformational lead-

ership (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.