Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

1

Research Brief

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support

Small Business Activity?

Chris Wheat and Chi Mac

December 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a widespread and prolonged

disruption to life in the U.S. since a national emergency was

declared on March 13, 2020. Small businesses saw substantial

revenue declines in the initial months (Farrell, Wheat, and Mac

2020a, 2020b). Expenses also declined commensurately,

reflecting lower revenues as well as efforts to preserve liquidity

(Farrell et al. 2020). Many small businesses have adapted to current

economic conditions, and while some have fully recovered, others

have not. Figure 1 shows that among small businesses that were

operating before the pandemic, median expenses in August 2021

were 10 percent below their January 2020 levels. However, median

balances remain elevated relative to their January 2020 levels.

Several relief and stimulus programs have contributed to deposit

account balances during the pandemic, including the Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP), Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL)

advances, Economic Impact Payments (EIP), and the expanded

advance Child Tax Credit (CTC).

1

The signature program for small businesses was the PPP, which

distributed nearly $800 billion in 2020 and 2021 through 11.8

million loans to small businesses nationwide.

2

Box 1 provides

additional summary details about the program. This research will

help policymakers evaluate the large fiscal expenditure required

to support the program and provide insight to the design

considerations of future relief programs. In particular, our research

offers insights about two features of the PPP: the large number of

relatively small loans and the duration of what was initially

short-term relief. Our findings shed light on the effects of smaller

loans, as nearly 69 percent of PPP loans in 2020 and 87

percent of those in 2021 were $50,000 or less (Small Business

Administration 2020a, 2021). Other studies have focused on loans

greater than $150,000. In addition to the PPP, state and local

programs often offered smaller amounts or limited eligibility to

smaller small businesses, and our research could have implications

for their programs as well. For example, the New York State

Pandemic Small Business Recovery Grant Program offered grants

ranging from $5,000 to $50,000 to small businesses with 100 or

fewer employees.

3

Ohio’s Small Business Relief Grant provided

$10,000 to small businesses with no more than 25 employees.

4

Our results inform not only the magnitude but also the

duration of any PPP effects. The program was initially designed

with an 8-week covered period under the expectation that firms

would spend their proceeds during this time. However, as the

pandemic evolved, this covered period was revised to 24 weeks,

although the maximum loan amounts remained unchanged. Our

analysis can provide insight into the duration of effects as well as

whether the revised covered period provided the flexibility small

businesses needed.

In this brief, we analyzed the magnitude and duration of any

effects the PPP had on business operating activity, as measured by

expenses and in comparison to a control group. While expenses

materially increased among small businesses that received PPP in

the week loan proceeds were received (Wheat and Mac 2021), there

is less evidence about whether expenses increased more among

PPP recipients than non-recipients.

Key Findings

• Finding 1: Upon PPP receipt, small business expenses increased by over 40 percent relative to a comparison group, with

significant but declining effects over four months.

• Finding 2: The impact of PPP loans on expenses was largest in April and May 2020, when small business expenses were

particularly depressed.

• Finding 3: The smallest firms experienced larger spending effects upon loan receipt, perhaps because they were more liquidity

constrained than larger firms.

• Finding 4: Restaurants may have used PPP loan proceeds to frontload expenses.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

2

Figure 1: Small business revenues and expenses have not rebounded to January 2020 levels, although balances are higher

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

Jan

2021

Mar

2021

May

2021

Jul

2021

−50%

−25%

0%

25%

50%

Median changes in firm balances, revenues, and expenses relative to January 2020

Percent change

Note: Sample includes small businesses operating January 2019 to February 2020.

Balances

Revenues

Expenses

View text version

Based on de-identified administrative data from bank

accounts, our research provides new evidence of the effect

of PPP loans—particularly smaller loans—on small business

activity. Other research on PPP has focused on employment

outcomes, often among firms receiving loans of more than

$150,000 compared to firms ineligible for PPP. For example,

there were small positive employment effects and reduced

business closure among employer firms that applied for PPP

loans greater than $150,000, relative to a control group of

firms with 500-1,000 employees (Hubbard and Strain 2020).

Firms receiving PPP loans increased employment by 7.5

percent relative to firms ineligible for PPP (Autor et al.

2020). Employment rates at firms with fewer than 500

employees, which would have been eligible for PPP,

increased by 2 percentage points compared to firms with

more than 500 employees (Chetty et al. 2020).

Our research differs in several aspects: First, our sample

consists largely of smaller loans to nonemployer and small

employer firms. Second, our control group also consists of

small businesses, so the comparison is between firms with

and without observed PPP funds in the given period, not

between the small businesses that were eligible and the

large businesses that were ineligible for the program. Third,

we focus on business expenses as the outcome variable, as

a proxy for business activity, which is particularly relevant

because we do not observe electronic payroll payments for

most of our sample.

5

Fourth, our period of analysis extends

through the end of 2020. As the pandemic extends into its

second year, policymakers may be interested in the duration

of any PPP effects.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

3

Box 1: Background on the PPP

The PPP was a complex program with guidelines that changed over time. The following provides a summary

of key dates and program features. It is not an exhaustive reference of relevant legislation or rules.

Key dates

• March 27, 2020: PPP established by CARES

Act with initial funding of $349 billion

a

• April 27, 2020: PPP loan applications resumed

b

after an additional $310 billion authorized

c

• June 5, 2020: Paycheck Protection Program

Flexibility Act

d

revised full loan forgiveness

terms to require at least 60 percent of

proceeds to be spent on payroll during

24 weeks after loan disbursement

• August 8, 2020: Application period closed

e

• December 27, 2020: Consolidated

Appropriations Act authorized $284 billion

f,g

• January 11, 2021: First draw loans reopened,

and second draw loans reopened two days later

h

• March 4, 2021: Nonemployers may use

gross income to calculate loan amount

i

• May 31, 2021: Applications closed; banks have

additional 30 days to process applications

j

Summary guidelines

• Eligibility: Entities with 500 or fewer

employees, including self-employed

individuals, sole proprietorships, and

independent contractors;

k

for second draw

loans in 2021, no more than 300 employees

and can demonstrate at least a 25 percent

reduction in gross receipts between

comparable quarters in 2019 and 2020

l

• Loan forgiveness: Initially, at least 75 percent

of proceeds must be spent on payroll costs

during the 8-week covered period following

loan disbursement; revised June 5, 2020 to

60 percent and 24 weeks, respectively

m

• Maximum loan amount: 2.5x average

monthly 2019 payroll costs or 2.5x net profit

n

for nonemployers; after March 4, 2021,

nonemployers may use gross income

o

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

4

We analyzed a de-identified sample of small businesses with

Chase Business Banking accounts that received exactly one

PPP loan inflow between 2020 and 2021. Within this sample,

we identified a treated group consisting of firms that received

PPP loans between April and August of 2020, which we

divided into cohorts based on the month in which they

received PPP loan proceeds.

6

May was the largest cohort,

comprising 77 percent of the 2020 loans in this analysis. We

compared each monthly loan cohort to a control group of

small businesses that did not receive PPP loans in 2020 but

did receive them in 2021, suggesting that this group was likely

eligible in 2020 as well and therefore comparable to those

with loans in 2020.

We used firm expenses as a measure of activity because it

may be less dependent upon customer demand or pandemic-

related operating restrictions. Earlier analysis showed that

expenses were more responsive to PPP loan inflows than

revenues (Wheat and Mac 2021). Figure 2 shows the median

change in expenses for the May cohort and the control

group, relative to their respective January 2020 values,

during the months between November 2019 and December

2020. Some overall trends are evident, such as decreasing

expenses in April followed by increasing expenses. While the

May cohort experienced a sharp increase in expenses when

PPP funds were received, the entirety of that increase cannot

be attributed to PPP, as the control group’s expenses also

increased in May but to a lesser extent. In subsequent months,

the difference between the groups narrowed. Our model was

estimated over this period

7

to include several months prior

to the pandemic and several after receipt of PPP loans. This

brief focuses on the estimated effects across these 14 months.

Methodology

Figure 2: Firms receiving PPP increased expenses more sharply than the control group

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−30%

−20%

−10%

0%

10%

Median change in small business expenses relative to January 2020

Percent change

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Note: Sample includes small businesses that received PPP in May 2020 or January to June 2021 (control).

May cohort

Control

Firms receiving PPP in May 2020 sharply

increased spending in month of receipt

View text version

To estimate the effects of PPP for each loan cohort relative

to the control group that is also responding to the pandemic,

we used a difference-in-difference event study. In this

framework, we look not at the difference between the

average expenses of the treated and control groups, but

rather the difference in how each group’s expenses changed

after the event in question. That is, the first difference was

the change each group experienced after PPP, some of

which may have been due to the pandemic’s evolution.

The difference between the treated and control groups’

differences therefore provided an estimate of how receiving

PPP loans changed the trend in business activity.

All of our estimates of PPP’s impact on expenses used the

difference-in-difference framework, which also implies that

any estimates prior to the treatment—receipt of PPP loans—

should be near zero despite potential level differences

between the two groups. The Methodological Appendix

discusses the sample and model in greater detail.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

5

Finding One: Upon PPP receipt, small business expenses

increased by over 40 percent relative to a comparison

group, with significant but declining effects over four

months. Across the loan cohorts, small businesses with

PPP loans increased their spending significantly for several

months after loan proceeds were received, relative to the

control group, although the effect diminished over time.

We summarized the overall effects of PPP over time by

calculating the weighted average effect across cohorts

for each month relative to the month of loan receipt. We

weighted each cohort’s estimate by its sample size, using

a method proposed by Callaway and Sant’Anna (2020).

As the May cohort was our largest, those estimates drive

the overall shape of the effects.

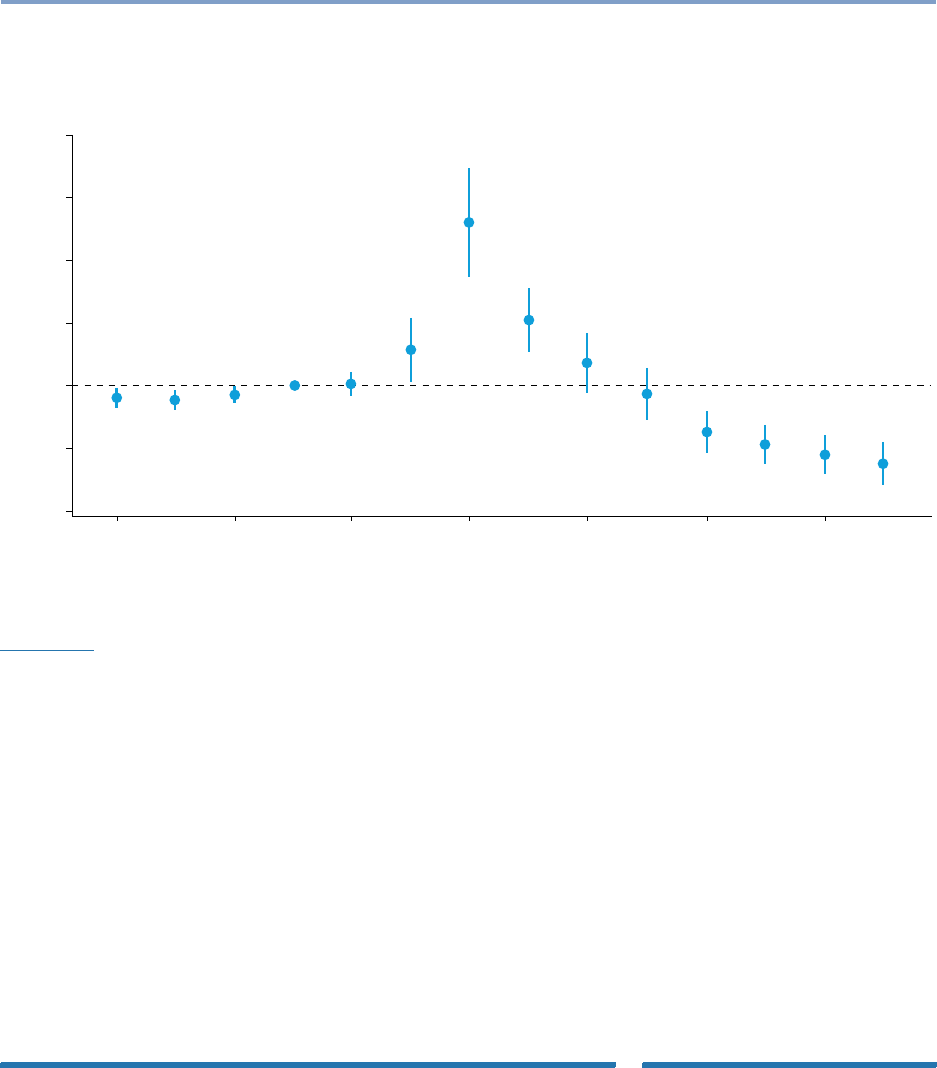

Figure 3 shows that small businesses with PPP loans

increased their expenses by more than those in the control

group for several months after receiving the loans. During

the initial month when small businesses received loan

proceeds, expenses changed by over 40 percent more than

changes in the control group’s expenses. Firms quickly

deployed loan inflows to pay expenses, suggesting that

cash liquidity was an imminent concern that was alleviated

by PPP. This effect declined over time: by the fifth month,

the effect was near zero. While the decline over time may

not be surprising, our estimates show that the effect on

firm expenses persists for approximately four months after

loan receipt. Notably, this duration was less than the

24-week covered period.

The PPP was designed to offer short-term cash liquidity to

small businesses, although the guidelines for using the

funds were later revised from 8 to 24 weeks.

8

Our results

suggest that there was a relatively large initial effect on

expenses, followed by an effort to stretch PPP funds over

several months, but any effects had diminished before

24 weeks had elapsed. Firms may have timed their

expenditures to occur within the guidelines, but the

declining effects suggest that the 24-week guideline

provided adequate flexibility.

Figure 3: Upon receipt of PPP, small business expenses increased by 42 percent relative to the control group, with declining

effects over time

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

42%

25%

11%

6%

3%

0 1 2 3 4

Effect of PPP on small business expenses among 2020 recipients

Number of months since PPP receipt

Note: Estimates are for 2020 PPP recipients compared to a control group.

View text version

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

6

Finding Two: The impact of PPP loans on expenses was

largest in April and May 2020, when small business

expenses were particularly depressed. The PPP was

established relatively quickly and emphasized the rapid

disbursement of funds under the assumption that small

businesses needed immediate relief. Many small businesses

applied soon after applications opened, but others did not.

We analyzed differences between the cohorts to understand

how contemporaneous circumstances can affect the

magnitude or duration of the impact on expenses. The

differences between cohorts also provides insight into

potential anticipatory effects, which can have implications

on how future relief programs are structured.

During April and May of 2020, the effect of receiving loans

on expenses—relative to the control group—was larger than

the effect for firms receiving loans in subsequent months.

The April and May cohorts comprised 84 percent of 2020

loans in our sample, and the initial effects observed in

these cohorts are relatively large. The upper panels of

Figure 4 show that changes to these cohorts’ expenses

in May 2020 were about 50 percent higher than the

changes in the expenses of the control group. In

hindsight, April and May 2020 represented two months

with particularly low expenses in the downturn related

to the pandemic, as shown in Figure 1 and Farrell et al.

(2020). This suggests the cash infusion was particularly

effective in supporting expenses during a period in which

firms would have otherwise restrained their spending.

However, there may be some selection effects, as we do not

know why some firms applied later. Early in the program,

not all details, especially about loan forgiveness, were

clear.

9

Firms applying for loans earlier may have been more

severely affected by the pandemic, while those waiting

until later could have had less immediate need or other

funding options. Alternatively, firms applying earlier may

have been more confident that they would be able to repay

a loan in the event they did not qualify for forgiveness.

We do not observe these or other potential contributing

factors. The Appendix provides details about the cohorts.

In contrast, the lower panels of Figure 4 show that during

the month of loan receipt, changes to the June and July

cohorts’ expenses were 15 and 22 percent higher,

respectively, than the changes to the control group’s

expenses. In the summer of 2020, small businesses saw

some recovery as capacity constraints eased or as they

found new ways to serve their customers. The effect of

receiving PPP funds could have been lower in these months

because they were measured relative to small businesses

whose circumstances were also improving despite not

receiving loans.

Figure 4: PPP loans had larger effects on small business expenses in April and May 2020

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Effect of PPP on small business expenses by 2020 cohort

Note: Sample for each cohort includes firms that received PPP in the given month and the control group. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Month of PPP receipt

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Effect of PPPEffect of PPP

April

May

June

July

Four months after PPP receipt

Nov

2019

View text version

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

7

For each cohort, we saw no statistically significant

differences between the treated and control groups in

the pre-treatment period. In each panel of Figure 4, the

estimated differences in the months before loan receipt is

near zero, with one exception, which we discuss below. This

is consistent with observing parallel trends between the

treated and control groups prior to receipt of the loan.

That is, their expenses were exhibiting similar trends before

PPP loan proceeds were received.

The May cohort exhibited increasing expenses relative to

the control group in April, the month before loan receipt.

This raises questions about the existence of potential

anticipatory effects—effects that can have important

implications for policymakers designing future programs.

There are two potential channels for anticipatory effects.

First, upon the establishment of the PPP, firms that

expected to be eligible for loans may have started to

spend even before applying. If that were the case, then a

program announcement would begin to impact behavior,

implying that timely announcements are critical to the

policy response. We did not find evidence consistent with

this type of anticipatory effect.

A second, narrower, channel is possible in the period

between loan approval and the receipt of loan proceeds.

Firms may have been comfortable spending knowing

their loans were approved but before the funds were

posted to their accounts. Our analysis suggests the

anticipatory effect seen in the May cohort was consistent

with the latter, due to the timing of the reopening of the

program, the loan application and approval process, and

the receipt of funds.

The PPP reopened on Monday, April 27, 2020, and

applications were processed and approved in the subsequent

days. The loan proceeds from this set of applications were

often posted to accounts in early May, but firms would

have learned of their loan approvals prior to receiving the

funds and some may have begun spending based on

that knowledge. To investigate this, we estimated our

model specification using four-week periods instead of

calendar months. For example, one four-week period

was Sunday, April 26 through Saturday, May 23, 2020

so the entire period encompassed both the reopening

of PPP and the funding of those applicants. There was

no statistically significant anticipatory effect in the

prior period, supporting the interpretation that small

businesses started spending following approval, not

simply because they were eligible for the program.

We also did not find anticipatory effects in subsequent

cohorts who were eligible for PPP, but applied and received

loans later. Similar to the May cohort, firms in other cohorts

could have begun spending after receiving loan approvals

and before receiving loan funds. However, in other months,

loans were not clustered at the beginning of the month,

so this pattern was less apparent.

The PPP required full disbursement of the loan within 10

calendar days of loan approval,

10

limiting this type of

anticipatory effect. This channel may be relevant for

programs with longer funding timelines. For example,

firms that have been approved for loans but are liquidity

constrained may nevertheless need to wait until they receive

the funds before they can start spending. Prior to the

pandemic, the typical small business had about two weeks

of cash liquidity, and long waits for funds may strain the

finances of many small businesses (JPMorgan Chase

Institute 2020).

The PPP provided cash liquidity to small businesses during

the pandemic and emphasized rapid disbursement of funds.

Our results suggest the cash infusion was particularly

effective in supporting expenses during April-May 2020,

when firms experienced severe disruptions to other inflows.

Our results also imply that some firms changed their

spending behavior before they received the funds, an effect

we will discuss further in the next finding.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

8

Finding Three: The smallest firms experienced larger

spending effects upon loan receipt, perhaps because

they were more liquidity constrained than larger firms.

Only small businesses were eligible for the PPP, but the

small business sector spans a wide range of firm sizes.

Among both PPP and non-PPP recipients, the vast majority

of small businesses—81 percent—were nonemployers and

another 17 percent were employers with fewer than 20

employees (Small Business Administration 2020b). The

effects of receiving loans may vary based on firm size. For

example, Hubbard and Strain (2020) found some evidence

that PPP was more effective among smaller firms in their

sample.

11

We investigated the differential effects of PPP

on business expenses by firm size and found that smaller

firms experienced larger effects in the month loan proceeds

were received. However, smaller firms exhibited lower

anticipatory effects in April, consistent with being more

liquidity constrained than their larger counterparts.

We used our largest cohort to analyze differences by firm

size. We separated the firms in our May sample, including

both the May loan recipients and the control group, into

quartiles based on their annual expenses in 2019

12

and

estimated the same model. The first quartile included firms

with annual expenses up to $191,000, while the fourth

quartile consisted of firms with annual expenses over

$991,000.

Figure 5 shows that smaller firms experienced larger

effects on expenses in the month loan proceeds were

received. For firms in the first size quartile, the increase

in May expenses was 61 percent higher than the change

experienced by the control group. In comparison, the

effect was 38 percent for the firms in the fourth quartile.

In addition, the positive effect on expenses lasted fewer

months for smaller firms: three months for the first quartile

compared to four months for the fourth quartile firms.

Figure 5: The smallest firms had larger effects on expenses in the month of PPP loan receipt and smaller anticipatory effects than

the largest firms

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Effect of PPP on small business expenses by firm size within May cohort

Note: Firms in quartile 1 had 2019 expenses below $191,000. Firms in quartile 4 had expenses greater than $991,000. Treated sample includes firms that received PPP

in May 2020, subsampled by 2019 expenses. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Effect of PPP

Quartile 1 Quartile 4

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Larger anticipatory

effect in April

Month of PPP receipt

Four months after PPP receipt

Larger effect among

small firms in month

of PPP receipt

View text version

The anticipatory effect in April was smaller for firms in

the first quartile, about 8 percent, compared to the 19

percent estimated for firms in the fourth quartile in the

same month. One explanation for this difference could be

that the smallest firms were less able to start spending

prior to receiving the loan proceeds, perhaps because

they did not have the cash liquidity from other sources

to draw upon. Larger small businesses could have been

more willing or able to start spending prior to actually

receiving loan proceeds. This suggests that cash liquidity

was more critical for the smallest small businesses.

Larger effects on expenses after the receipt of loan

proceeds and the smaller anticipatory effect both suggest

that cash liquidity may be more critical to the spending

decisions of smaller small businesses. The PPP required

loan disbursements within 10 calendar days of approval,

limiting this type of anticipatory effect. However, it could

be a consideration in the design of future programs.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

9

Finding Four: Restaurants may have used PPP loan

proceeds to frontload expenses. Restaurants have been

particularly hard hit during the pandemic. While many

restaurant owners adapted their business models to

changing economic conditions related to the COVID-19

pandemic, these changes may not have been sufficient to

compensate for evolving consumer demand. Their recovery

has lagged behind small businesses in other industries.

13

The challenges faced by small restaurants provided an

opportunity to better understand how short-term relief may

have been used by firms facing longer term disruption more

broadly. We used the May cohort, which offers the largest

sample size, and restricted it to restaurants in this model.

Similar to what we saw across our sample, small restaurants

also increased their expenses relative to the control group

during the initial months after receiving their loans, as

shown in Figure 6. However, the significant positive effect

did not last long—just two months after receiving the

loan proceeds—although there was an anticipatory effect

in April. However, beginning in September 2020, the change

in expenses for restaurants with PPP loans was significantly

lower than the control group.

Figure 6: Restaurants initially increased expenses upon PPP loan receipt, but changes to spending later in 2020 were lower than

the control group

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Effect of PPP on expenses of restaurants in the May cohort

Note: Sample includes restaurants that received PPP in May 2020 compared to restaurants in the control group. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Effect of PPP

Nov

2019

Jan

2020

Mar

2020

May

2020

Jul

2020

Sep

2020

Nov

2020

−50%

−25%

0%

25%

50%

75%

100%

View text version

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

10

Our difference-in-difference framework does not

estimate differences in expense levels between groups

but rather differences in how each group changes.

Over the entire period, restaurants with PPP had higher

average expenses than the control group. However, our

results suggest they frontloaded those expenses in the

initial months after receiving their loan proceeds.

Figure 7 shows the ratio of average monthly expenses to

the average over the April to December 2020 period for

each group. If monthly expenses were perfectly smooth

over time, then this ratio would equal 1 in each month. That

is, each month’s average expense is the same as in other

months. For restaurants with PPP loans in May, monthly

expenses were higher early in the period and shortly after

receiving loan proceeds. Later in 2020, expenses were lower

than their period average. Among restaurants in the control

group, we saw a different pattern. Average expenses in May

were lower than their period average and more gradually

increased. In autumn of 2020, average expenses for the

control group were increasing when those of the treated

group were decreasing, resulting in the negative difference-

in-difference estimates. This suggests that restaurants

receiving PPP funds in May were able to frontload more

expenses in the initial weeks, perhaps investing in outdoor

seating or an online presence. In contrast, firms without PPP

loans could have delayed or spread out similar expenses.

View text version

Figure 7: Restaurants with PPP spent more soon after receiving funds, while the control group ramped up spending later in 2020

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Ratio of monthly restaurant expenses to April through December average

Note: Sample includes restaurants that received PPP in May 2020 and restaurants in the control group.

Ratio

Apr

2020

May

2020

Jun

2020

Jul

2020

Aug

2020

Sep

2020

Oct

2020

Nov

2020

Dec

2020

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

Control group:

Higher than average

expenses later in period

PPP recipients:

Higher than average

expenses earlier in period

Small businesses in other industries may have also used

their PPP loan proceeds to frontload expenses. However,

that pattern may be obscured in industries that have

experienced more robust recoveries, such as health care

and professional services. It is perhaps not a coincidence

that we observe this pattern in restaurants and, to a lesser

extent, personal services, two of the hardest hit industries

during the pandemic.

Our model estimates illustrate that the experiences of small

businesses during the pandemic—including experiences

with relief programs such as PPP—varied by industry.

Their experiences suggest the need for industry-specific

considerations alongside broader policy interventions.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

11

The PPP was an unprecedented program designed to

support small businesses through the pandemic. This brief

provides insight into the magnitude and duration of the

effect of PPP loans on small business expenses. With this

context in mind, we offer the following implications for

leaders and decision makers seeking to support small

businesses during periods of severe economic disruptions:

Small businesses need flexibility in how and when to

use relief funds. Policymakers want to ensure that relief

funds are used promptly and effectively. However, the wide

range of small businesses implies that they may face a wide

range of challenges resulting from the same disruption.

Policymakers did recognize this during the pandemic and

revised some PPP rules, such as increasing the time for

using the loan proceeds from 8 to 24 weeks and decreasing

the share of funds to be used on payroll expenses from 75

to 60 percent. As the pandemic evolved, some sectors may

have needed different strategies for how and when to use

their loan proceeds. More generally, relief programs should

consider the need for flexibility along with the need for

structure and guidelines.

Timeliness is an important factor in effective relief. Our

research demonstrates that PPP’s largest impact on business

expenses was in April and May 2020, when business

spending was particularly depressed. The CARES Act was

passed relatively quickly, establishing several different relief

programs, including the PPP. The timeliness of this action

may have been critical given the sudden disruption caused

by the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, typical small

businesses had about two weeks of cash liquidity, with

Black- and Latinx-owned businesses having lower cash

buffers than White-owned ones (JPMorgan Chase Institute

2020; Farrell, Wheat, and Mac 2020c). Nevertheless, in

designing relief programs, policymakers must balance

the need to disburse relief funds quickly with competing

goals, such as considering those who have been most

severely affected, collecting data and documentation from

applicants, or mitigating the risk of fraud.

Targeted policies could be appropriate, depending on

the circumstances. A widespread emergency such as the

pandemic required a relief program that was just as broad.

However, the related economic disruption was not

experienced evenly across the small business sector, as

restaurants and personal services have been more severely

affected than other industries. During the pandemic, the

Restaurant Revitalization Fund

14

and Shuttered Venue

Operator Grants

15

offered additional assistance, but they

were not available until 2021. Depending on the

circumstances of the economic disruption, policymakers

should consider a possible role for more targeted

interventions. Examples include industry-specific programs,

perhaps as complements to broader programs, or using

maximum loan amounts to focus relief efforts.

Conclusions and Implications

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

12

To analyze the effects of PPP on small business expenses,

we created a sample of de-identified small businesses that

were similar but for their observed receipt of PPP loans.

Firms included in our sample, either in a treated or control

group, have Chase Business Banking accounts and exactly

one observed PPP loan. The PPP lender could be Chase,

as it was in 78 percent of our sample, or another lender.

16

To reduce confounding factors, we excluded any firms

that received either more than one PPP loan or an EIDL

advance. It is possible that firms in our sample had access

to other sources of funding during the period of analysis.

Our estimates used expense data derived from the de-

identified deposit account transactions from November

2019 through December 2020. To ensure that we were

not measuring expenses during firms’ startup phases,

we required that the accounts were open for at least a

year prior to November 2019 with activity during each

month of the pre-pandemic period. Accounts also must

have stayed open through the end of December 2020,

but accounts did not need to have activity in every

month of 2020.

17

Satisfying the criteria for inclusion in

our sample necessarily means that we neither included

every PPP loan originated by Chase nor did we include

only those originated by Chase.

18

A careful reader of our

reports will notice that the typical firm in this sample

was somewhat larger than those in our other reports.

Using this sample, we separated the 2020 PPP loan

recipients into cohorts based on the month the loan

proceeds were posted into the deposit accounts. Each

cohort represents a treated group. The control group

was the same for each treated group: firms with their

first and only PPP loan in 2021. Therefore, they were

not-yet-treated during the estimation period which ends

in 2020. However, the fact they received a PPP loan in

2021 implies they likely would have qualified in 2020.

Firms that did not apply by August 2020 would not have

known of future opportunities to apply until legislation

reauthorizing the PPP was signed in late December 2020.

There may have been differences between firms receiving

PPP loans earlier, compared to those receiving loans later.

However, for our research design, differences between

treated and control groups are acceptable as long as they

followed parallel trends prior to the treatment. Firms

applying earlier could have had greater need; firms applying

later could have been waiting for clearer guidelines. Table

A1 shows the median loan sizes across cohorts. The typical

loan amount in our May cohort was $27,000, compared to

$11,000 in the July cohort. The median loan amount among

the 2021 loans in our sample was $17,000. The publicly

available data from the SBA show similar trends. Loans

approved in May 2020 had a median size of $19,000, while

the median among those approved in July was $13,000.

Limited to the loans under $150,000, which is more

comparable to our sample, a similar pattern of larger loans

earlier emerges. However, some nonemployer firms would

have qualified for larger loans in 2021 than in 2020. A rule

change allowed them to calculate their maximum loan

amount based on gross income instead of net income.

19

We did not include firms that never received a PPP loan

in the control group because while some of these firms

may have served as appropriate controls, others may have

been ineligible for the PPP. Survey data indicated that

nonemployer firms were less likely to apply for PPP than

employers, with the most common reason cited as the

expectation that they would not qualify either for the loan

or for loan forgiveness (Federal Reserve 2021a, 2021b).

Other reasons included confusion about the program, not

needing funding, or seeking other funding. The Federal

Reserve also noted that 30 percent of nonemployers

collected unemployment insurance benefits (2021b),

20

which could have been an alternate avenue for relief.

Methodological Appendix

Sample

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

13

Table A1: Median loan amounts and share of loans, by sample and cohort

Table A2: Industry composition, by sample and cohort

Table A2 shows that the industry distribution in our sample

was similar to the distribution across those industries for

all loans reported by the SBA. However, our sample was

more heavily weighted in industries common in greater

metropolitan areas. For example, our sample included a

larger share of firms in health care and professional services.

Our sample did not include industries for which we did not

have a representative sample, including transportation and

warehousing, as well as agriculture, forestry, fishing, and

hunting.

JPMCI sample SBA data

Firms Median loan amount Share of loans

2020 PPP loans Median loan amount Count Share $150k and under All loans $150k and under All loans

April $59,000 3,508 7% $27,000 $38,000 52% 56%

May $27,000 36,303 77% $18,000

$19,000 32% 29%

June $14,000 4,106 9% $13,000 $13,000 9% 8%

July $11,000 2,641 6% $13,000 $13,000

5% 4%

August $11,000 728 2% $13,000 $14,000 2% 2%

Total 47,286 100% 100% 100%

2021 PPP loans $17,000 6,657 $19,000 $20,000

JPMCI sample SBA data

2020 loans

April May June July August 2021 loans Overall

$150k and

under

All loans

Other professional services 20% 17% 13% 14% 14% 17% 17% 14% 14%

Health care services 16% 16% 15% 16% 14% 12% 15% 11% 11%

Retail 11% 13% 12% 12% 13% 12% 13% 13% 13%

Construction 12% 13% 14% 14% 15% 16% 13% 14% 14%

Restaurants 9% 10% 10% 8% 9% 10% 10% 9% 10%

Repair & maintenance 7% 8% 8% 9% 8% 9% 8% 9% 9%

Personal services 5% 7% 13% 13% 12% 11% 8% 16% 15%

Wholesalers 7% 7% 5% 5% 5% 5% 6% 5% 5%

Real estate 5% 5% 5% 5% 5% 3% 5% 7% 6%

High-tech services 5% 4% 3% 2% 3% 3% 3% 2% 2%

Metal & machinery 2% 1% 1% 1% <1% 1% 1% 1% 2%

High-tech manufacturing <1% <1% <1% <1% <1% <1% <1% 0% 0%

100%

100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100%

Selected industries as share of total 62% 62%

JPMCI sample includes firms with one PPP loan from Chase or another lender and meet our criteria for deposit account activity. Loan cohorts are based on the date loan

proceeds were posted to deposit accounts. Firms with loans approved in the last week of April 2020 received their funds in early May.

SBA tabulation is based on available data as of June 30, 2021. Loan cohorts are based on loan approval date.

JPMCI sample includes firms with one PPP loan from Chase or another lender and meet our criteria for deposit account activity.

SBA tabulation is based on available data as of June 30, 2021.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

14

Model

We used a difference-in-difference event study to estimate the effect of receiving PPP loans on expenses over time.

We were particularly interested in how long any effects might persist, as the pandemic has lasted longer than expected.

An advantage of the difference-in-difference framework is that level differences between the treated and control groups

are acceptable as long as the two groups are following parallel trends prior to the event of interest.

Using our May cohort and control group as an example, the average log expenses of May cohort was larger than that of

the control group, but the difference between them was stable. After May 2020, small business expenses could have been

recovering for both the treated group of firms with PPP loans as well as for the control group, but it is the difference in

how each group’s expenses changes—the difference in the differences—after May that is of interest.

The equation above shows the regression model estimated. We chose expenses as a proxy for business activity for two

reasons. First, unlike revenues, it is possible for expenses to be independent of consumer demand or pandemic-related

restrictions. Consider a business that was not permitted to operate or perhaps chose not to operate during the pandemic

and therefore generated no revenue. Another possibility is if the business did continue to operate, but customer demand

was limited due to the pandemic. However, the firm could have—using PPP loan proceeds or other funds—continued to pay

its employees, utilities, and other expenses. To the extent that PPP facilitated this continuity despite a disruption in

revenues, we would want to consider its expense activity. Moreover, expenses are often highly correlated with revenues

(Farrell et al. 2020), making it an appropriate proxy for business activity. Expenses, which include payroll expenses, are

defined as outflows that are not related to financing. Financing could include transfers to personal accounts or loan

repayment.

21

We observed electronic payroll payments in 37 percent of firms in our sample.

The model for each loan cohort in 2020 was estimated separately with the same control group of firms with 2021 PPP

loans.

22

For example, the May cohort included firms with May 2020 PPP loans in the treated group and firms with 2021

PPP loans in the control group.

23

Groups were weighted so that the treated and control groups each represented half of

the sample. Our model was estimated at the firm-month level using the above equation, where f indexed the firm and m

indexed the month. The variable PPP

f

is a dummy variable equal to one if the firm was in the PPP month cohort, and Month

m

is a dummy variable for the month.

24

Also included are controls for industry, state, and month.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

15

Data Explanation

Figure 1: Median changes in firm balances, revenues, and expenses relative to January 2020

Line chart showing median changes in small business balances, revenues, and expenses relative to January 2020 in each calendar month from

November 2019 through August 2021. The balance line shows that median balances increased in April 2020 and stayed at elevated levels through

August 2021, relative to January 2020. The revenues and expenses lines show that median revenues and expenses fell to -30 percent of January

2020 levels in April 2020 and remained below January 2020 levels in most months through August 2021.

View chart version

Figure 2: Median change in small business expenses relative to January 2020

Line chart showing the median change in expense relative to January 2020 for the May 2020 PPP recipient cohort and control group from

November 2019 through December 2020. The chart shows that expenses for each group were similar until April 2020, when the control group had a

larger drop in expenses, relative to January 2020, than the May 2020 PPP recipient cohort. The gap in expenses between the two groups is greatest

in May 2020, when the PPP recipients increased spending more sharply than the control group.

View chart version

Figure 3: Effect of PPP loans on small business expenses among 2020 recipients

Bar chart showing the estimated effect of PPP on small business expenses compared to the control group. Chart shows the estimates as the number

of months since PPP receipt on the x-axis, and ranges from 0 to 4 months. In the month of PPP receipt, expenses increased by 42 percent relative to

the control group, followed by 25 percent, 11 percent, 6 percent, and 3 percent in the subsequent four months.

View chart version

Figure 4: PPP had larger effects on small business expenses in April and May 2020

Four scatter plot charts with error bars at the 95 percent confidence interval showing the effect of PPP on small business expenses for each monthly

cohort: April 2020, May 2020, June 2020, and July 2020. Estimated effect shown for every calendar month between November 2019 and December

2020. Chart shows almost no difference between each cohort and the control group prior to PPP receipt for the April, June, and July cohorts. The

May cohort shows expenses increased by 13 percent more than the control group in April 2020 compared to the control group. Expenses for the

April cohort increased by 37 percent relative to the control group in April 2020, expenses for the May cohort increased by 47 percent more than the

control group in May 2020, expenses for the June cohort increased by 14 percent more than the control group in June 2020, and expenses for the

July cohort increased by 22 percent more than the control group in July 2020. Charts show that in all cohorts the effect of PPP on small business

expenses diminishes to zero within four months of PPP receipt and then no difference with the control group through the end of the year.

View chart version

Figure 5: Effect of PPP on small business expenses by firm size within May cohort

Scatter plot charts with error bars at 95 percent confidence interval showing the effect of PPP on small businesses in the May cohort sized by 2019

expenses. Estimated effect shown for every calendar month between November 2019 and December 2020 for the first and fourth quartiles of firm

expenses. Among small businesses in both quartiles there is almost no difference in expenses until April 2020. Small businesses in quartile 1 have

changes to expenses that are 8 percent higher than the control group in April 2020, and small businesses in quartile 4 have changes that are 19 per-

cent higher than the control group in April 2020. Expenses for small businesses that received PPP in the first quartile of 2019 expenses increased by

61 percent more in May 2020 than the control group, expenses for small business that received PPP in the fourth quartile of 2019 expenses changed

by 38 percent more in May 2020 than the control group. The differences in effects between small businesses in both quartiles 1 and 4 and the con-

trol group diminish over the next four months, and there are no differences in effects at the end of 2020.

View chart version

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

16

Figure 6: Effect of PPP on expenses of restaurants in the May cohort

Scatter plot chart with error bars at 95 percent confidence interval showing the effect of PPP on restaurants in the May cohort. Estimated effect

shown for every calendar month between November 2019 and December 2020. Almost no difference in expenses between May PPP recipient

restaurants and the control group prior to PPP receipt. Expenses for restaurants that received PPP in May 2020 increased by 61 percent more than

expenses for the control group in May 2020. Changes to expenses for restaurants that received PPP in May 2020 were lower than those for the con-

trol group from September 2020 through December 2020.

View chart version

Figure 7: Ratio of monthly restaurant expenses to April through December average

Line chart showing monthly expenses from April 2020 through December 2020 as a ratio of the average monthly expenses over the entire period,

separated by restaurants that received PPP in May 2020 compared to the control group. Restaurants that received PPP in May 2020 had high-

er-than-average expenses from May 2020 through September 2020. The control group had higher-than-average expenses from July 2020 through

the end of the year.

View chart version

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

17

References

Autor, David, David Cho, Leland D. Crane, Mita Goldar, Byron

Lutz, Joshua Montes, William B. Peterman, David Ratner,

Daniel Villar, and Ahu Yildermaz. 2020. “An Evaluation of the

Paycheck Protection Program Using Administrative Payroll

Microdata.” Working paper. https://economics.mit.edu/

files/20094.

Callaway, Brantly and Pedro H.C. Sant’Anna. 2020. “Difference-

in-Differences with Multiple Time Periods.” Journal of

Econometrics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001.

Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, Nathaniel Hendren, Michael

Stepner, and the Opportunity Insights Team. 2020. “The

Economic Impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a New Public

Database Built Using Private Sector Data.” National Bureau of

Economic Research. Working Paper 27431. https://www.nber.

org/papers/w27431.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020a. “Small

Business Financial Outcomes during the Onset of COVID-19.”

JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020b. “Small

Business Financial Outcomes during the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

JPMorgan Chase Institute.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, and Chi Mac. 2020c. “Small

Business Owner Race, Liquidity, and Survival.” JPMorgan

Chase Institute.

Farrell, Diana, Chris Wheat, Chi Mac, and Bryan Kim. 2020.

“Small Business Expenses during COVID-19.” JPMorgan Chase

Institute.

Federal Reserve Banks. 2021a. “Small Business Credit

Survey: 2021 Report on Employer Firms.” https://www.

fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/

files/2021/2021-sbcs-employer-firms-report.

Federal Reserve Banks. 2021b. “Small Business Credit Survey:

2021 Report on Nonemployer Firms.” https://www.fed-

smallbusiness.org/medialibrary/FedSmallBusiness/

files/2021/2021-sbcs-nonemployer-firms-report.

Goodman-Bacon, Andrew. 2021. “Difference-in-differences with

Variation in Treatment Timing.” Journal of Econometrics.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014.

Hubbard, R. Glenn and Michael R. Strain. 2020. “Has the

Paycheck Protection Program Succeeded?” National Bureau

of Economic Research. Working Paper 28032. http://www.

nber.org/papers/w28032.

JPMorgan Chase Institute. 2020. “Small Business Cash

Liquidity in 25 Metro Areas.” https://www.jpmor-

ganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/

small-business-cash-liquidity-in-25-metro-areas.

Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker, Small Business

Revenue. 2021. https://tracktherecovery.org/?s91z8.

U.S. Small Business Administration. 2020a. “Paycheck

Protection Program (PPP) Report: Approvals through

08/08/2020.” 2020. https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/

files/2021-09/PPP_Report%20-%202020-08-10-508.pdf.

U.S. Small Business Administration. 2020b. “2020 Small

Business Profile.” https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/

uploads/2020/06/04144224/2020-Small-Business-Econom-

ic-Profile-US.pdf.

U.S. Small Business Administration. 2021. “Paycheck Protection

Program (PPP) Report: Approvals through 05/31/2021.”

https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/PPP_Report_

Public_210531-508.pdf.

Wheat, Chris and Chi Mac. 2021. “The Paycheck Protection

Program: Small Business Balances, Revenues, and Expenses

in the Weeks after Loan Disbursement.” JPMorgan Chase

Institute.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

18

Box 1: Endnotes

a CARES Act. https://www.con-

gress.gov/116/plaws/publ136/

PLAW-116publ136.pdf.

b Small Business Administration

Press Release Number 20-34,

April 24, 2020. https://www.

sba.gov/article/2020/apr/24/

joint-statement-sba-administra-

tor-jovita-carranza-treasury-secre-

tary-steven-t-mnuchin-resumption.

c Paycheck Protection Program and

Health Care Enhancement Act.

https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/

publ139/PLAW-116publ139.pdf.

d Paycheck Protection Program

Flexibility Act of 2020. https://

www.congress.gov/116/plaws/

publ142/PLAW-116publ142.pdf.

e PPP Extension Act of 2020. https://

www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-

116publ147/pdf/PLAW-116publ147.pdf.

f https://home.treasury.gov/

policy-issues/coronavirus/

about-the-cares-act.

g https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/

hr133/BILLS-116hr133enr.pdf.

h Department of the Treasury

Press Release, January 8, 2021.

https://home.treasury.gov/

news/press-releases/sm1230.

i “Business Loan Program

Temporary Changes; Paycheck

Protection Program-Revisions

to Loan Amount Calculation

and Eligibility.” Small Business

Administration. March 8, 2021.

https://www.federalregister.gov/

documents/2021/03/08/2021-04795/

business-loan-program-tem-

porary-changes-paycheck-pro-

tection-program-revi-

sions-to-loan-amount.

j PPP Extension Act of 2021. https://

www.whitehouse.gov/brief-

ing-room/legislation/2021/03/30/

press-release-bill-signing-h-r-1799/.

k PPP Information Sheet. https://

home.treasury.gov/system/

files/136/PPP--Fact-Sheet.pdf.

l “Paycheck Protection Program

Second Draw Loans: Top-Line

Overview.” Department of the

Treasury. https://home.treasury.

gov/system/files/136/Top-line-

Overview-of-Second-Draw-PPP.pdf.

m Department of the Treasury

Press Release, June 8, 2020.

https://home.treasury.gov/

news/press-releases/sm1026.

n “Paycheck Protection Program:

How to Calculate Maximum Loan

Amounts—By Business Type.” Small

Business Administration. June 26,

2020. https://www.sba.gov/sites/

default/files/2020-06/How-to-

Calculate-Loan-Amounts-508_1.pdf.

o Effective March 4, 2021. “Business

Loan Program Temporary Changes;

Paycheck Protection Program-

Revisions to Loan Amount Calculation

and Eligibility.” Small Business

Administration. March 8, 2021.

https://www.federalregister.gov/

documents/2021/03/08/2021-04795/

business-loan-program-temprary-

changes-paycheck-protection-pro-

gram-revisions-to-loan-amount.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

19

1 EIP and CTC were made to eligi-

ble individuals as opposed to firms.

However, the majority of small busi-

nesses at large and in our sample

are nonemployer firms. Pass-through

entities, such as sole proprietor-

ships, report net income on their

owners’ tax returns. If those tax

returns used the business’s direct

deposit information, the payments

could have been deposited into

the business checking accounts.

2 Based on approvals through

May 31, 2021 (Small Business

Administration 2021).

3 New York Small Business Pandemic

Recovery Initiative Fact Sheet (New

York State Senate, updated August

1, 2021). https://www.nysenate.gov/

newsroom/articles/2021/brad-hoyl-

man/new-york-small-business-pan-

demic-recovery-initiative-fact-sheet.

4 Small Business Relief Grant Fact

Sheet (Ohio Development Services

Agency). https://businesshelp.

ohio.gov/pdf/10292020-Small-

business-relief-grant.pdf.

5 We observed electronic payroll pay-

ments for 37 percent of firms in our

sample. However, not all firms with

employees use electronic payroll

processors, and there may have

been employer firms for whom we

did not observe payroll payments.

For example, they may have pro-

cessed payroll independently using

paper checks, as opposed to using

an electronic payroll processor.

6 We used the dates on which trans-

actions were posted to accounts.

Parties may be aware of pending

transactions prior to the post date.

7 The omitted period is February 2020.

8 Revised June 5, 2020 by the Paycheck

Protection Program Flexibility Act of

2020. https://www.congress.gov/116/

plaws/publ142/PLAW-116publ142.pdf

9 The interim final rule with details

on loan forgiveness was pub-

lished June 1, 2020. https://home.

treasury.gov/system/files/136/

PPP-IFR-Loan-Forgiveness.pdf.

10 Federal Register, Vol. 85, No. 86.

May 4, 2020. https://home.trea-

sury.gov/system/files/136/Interim-

Final-Rule-on-Disbursements.pdf.

11 Their sample consisted of firms

applying for PPP loans greater than

$150,000 (Hubbard and Strain 2020).

12 Firm size can be measured in

different ways. Commonly used

measures include the number of

full-time employees or annual

revenues. Since our model spec-

ification is based on expenses,

and revenues and expenses

are highly correlated, we used

expenses to categorize firm size.

13 Median small restaurant expenses

were 18 percent lower in September

2020 compared to the prior year;

among all small businesses, expenses

were 7 percent lower (Farrell et al.

2020). The Opportunity Insights

Economic Tracker reported that

small business revenue in the lei-

sure and hospitality industry was

59 percent lower at the end of

June 2021 than in January 2020.

In comparison, revenues among

all small businesses was 43 per-

cent lower than January values.

14 The $28.6 billion Restaurant

Revitalization Fund was estab-

lished by the American Rescue Plan.

Applications opened May 3, 2021

(Small Business Administration

Release Number 21-33). https://

www.sba.gov/article/2021/apr/27/

sba-administrator-guzman-announc-

es-application-opening-286-bil-

lion-restaurant-revitalization-fund.

15 The $16.2 billion Shuttered

Venue Operators Grants pro-

gram opened April 8, 2021 (Small

Business Administration Release

Number 21-28). https://www.sba.

gov/article/2021/apr/07/sba-open-

shuttered-venue-operators-grants-

applications-april-8-12-pm-edt.

16 We identified PPP loan inflows

from other lenders based on

transaction characteristics.

17 The resulting sample reflects sur-

viving firms in that their deposit

accounts remained open through

the end of 2020. However, firms

without transaction activity in their

open accounts were included in the

sample. This requirement was con-

sistently applied across treated and

control groups. The control group,

consisting of firms with 2021 PPP

loans, necessarily kept their accounts

open through 2020, as they depos-

ited their loan proceeds in 2021.

18 For example, Chase PPP loans

deposited into accounts other

than Business Banking accounts

would not be included. Also

excluded are firms with accounts

that do not meet our activity cri-

teria and firms that received PPP

loans in both 2020 and 2021.

19 Small Business Administration.

March 8, 2021. “Business Loan

Program Temporary Changes;

Paycheck Protection Program-

Revisions to Loan Amount

Calculation and Eligibility.” https://

www.federalregister.gov/docu-

ments/2021/03/08/2021-04795/

business-loan-program-temporary-

changes-paycheck-protection-pro-

gram-revsions-to-loan-amount.

20 Self-employed workers are usu-

ally not eligible for unemploy-

ment benefits, but the CARES

Act gave states the option to

extend benefits to them.

21 Deposit account transactions are

classified based on various trans-

action characteristics. Transactions

Endnotes

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

20

are aggregated to the month

based on the date the transac-

tion posted to the account.

22 Including all cohorts in one model

with staggered treatment may lead

to unexpected weighting across

cohorts (Goodman-Bacon 2021).

23 Within a month cohort, the loans

may have been received at differ-

ent times of the month, but this is

not modeled at our level of aggre-

gation. For our May cohort, which

is the largest in our sample, most

loan proceeds were deposited in

early May 2020 after PPP applica-

tions resumed on April 27, 2020.

24 February 2020 is the omitted month.

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

21

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicholas Tremper and Noah Forougi for their hard work and vital contributions to this research. Additionally,

we thank Emily Rapp and Robert Caldwell for their support. We are indebted to our internal partners and colleagues,

who support delivery of our agenda in a myriad of ways, and acknowledge their contributions to each and all releases.

We would like to acknowledge Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., for his vision and leadership in establishing

the Institute and enabling the ongoing research agenda. We remain deeply grateful to Demetrios Marantis, Head of

Corporate Responsibility, Heather Higginbottom, Head of Research & Policy, and others across the firm for the

resources and support to pioneer a new approach to contribute to global economic analysis and insight.

Suggested Citation

Wheat, Chris and Chi Mac. 2021. “Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity?”

JPMorgan Chase Institute. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/did-ppp-support-small-

business-activity.

For more information about the JPMorgan Chase Institute or this report, please see our website

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

22

The JPMorgan Chase Institute has adopted rigorous security protocols and checks and balances to ensure all customer data

are kept confidential and secure. Our strict protocols are informed by statistical standards employed by government agencies

and our work with technology, data privacy and security experts who are helping us maintain industry-leading standards.

There are several key steps the Institute takes to ensure customer data are safe, secure and anonymous:

• The Institute’s policies and procedures require that data it receives and processes for research purposes do not identify

specific individuals.

• The Institute has put in place privacy protocols for its researchers, including requiring them to undergo rigorous back-

ground checks, and enter into strict confidentiality agreements. Researchers are contractually obligated to use the data

solely for approved research, and are contractually obligated not to re-identify any individual represented in the data.

• The Institute does not allow the publication of any information about an individual consumer or business. Any data point

included in any publication based on the Institute’s data may only reflect aggregate information or information that is

otherwise not reasonably attributable to a unique, identifiable consumer or business.

• The data are stored on a secure server and only can be accessed under strict security procedures. The data can-

not be exported outside of JPMorgan Chase’s systems. The data are stored on systems that prevent them from being

exported to other drives or sent to outside email addresses. These systems comply with all JPMorgan Chase Information

Technology Risk Management requirements for the monitoring and security of data.

The Institute prides itself on providing valuable insights to policymakers, businesses, and nonprofit leaders. But these

insights cannot come at the expense of consumer privacy. We take all reasonable precautions to ensure the confidence and

security of our account holders’ private information.

JPMC Institute Public Data Privacy Notice

Did the Paycheck Protection Program Support Small Business Activity? Research Brief

23

This material is a product of JPMorganChaseInstitute and is provided to you solely for general information purposes. Unless

otherwise specifically stated, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may differ from

the views and opinions expressed by J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS) Research Department or other departments or divisions

of JPMorganChase&Co. or its affiliates. This material is not a product of the Research Department of JPMS. Information has

been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but JPMorganChase&Co. or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively

J.P. Morgan) do not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of

this material and are subject to change without notice. The data relied on for this report are based on past transactions and

may not be indicative of future results. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any

particular client and is not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, or strategies for a

particular client. This material does not constitute a solicitation or offer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.

Disclaimer

©2021 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved. This publication or any portion hereof may not be reprinted, sold, or

redistributed without the written consent of J.P. Morgan. www.jpmorganchaseinstitute.com