1

CRITICAL THINKING: THE VERY BASICS - ANSWERS

Dona Warren, Philosophy Department, The University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point

Argument Recognition, Analysis, and Evaluation

I’ve highlighted important parts of some arguments and my diagrams and comments

are in blue. In order to prevent inadvertent peeking at upcoming diagrams, I’ve put

only one argument on each page of this answer booklet.

Philosophy

Directions: For each of the following passages, determine whether or not it contains

an argument. If a passage does contain an argument, diagram it. You don’t need to

evaluate it.

1) “Studying philosophy helps us to excel in many other areas. Therefore, studying

philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor.”

Notice how the conclusion indicator expression “therefore” helps us to identify the

inference in this argument.

Studying philosophy helps us to excel in many other areas.

Studying philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor.

2

2) “Since philosophy cultivates the use of reason, studying philosophy helps us to

excel in many other areas.”

Notice how the reason indicator expression “since” helps us to identify the inference

in this argument.

Philosophy cultivates the use of reason.

Studying philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor.

3

3) “Studying philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor because philosophy addresses the

most interesting questions that there are.”

Notice how the reason indicator expression “because” helps us to identify the

inference in this argument.

Notice also that, due to the placement of “because” in this passage, the reason

for the conclusion

follows

the conclusion. The passage

first

state the conclusion and

then

states the reason for the conclusion. We might say that the “narrative order” of

the ideas in the passage – a conclusion followed by the reason - is the reverse of the

the “logical order” of these ideas – a reason followed by conclusion. (If you look at

the previous two arguments, you’ll see that the narrative order of the ideas was

identical to the logical order of the ideas, because in both passages, the statement of

the reason for the conclusion preceded the statement of the conclusion.)

It’s important to remember that reason indicator expressions like “because”

and “since” can switch the order like this.

“A therefore B” is ., but “A because B” is .

Studying philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor.

Philosophy addresses the most interesting questions that there are.

A

È

B

B

È

A

4

+

4) “Philosophy addresses the most interesting questions that there are. After all,

philosophy addresses questions that can’t be answered using standard empirical

methods and questions that can’t be answered using standard empirical methods are

always the most interesting.”

Notice how the reason indicator expression “After all” helps us to identify the

inference in this argument, and notice how – as with the previous argument – it shows

us that the reasons follow the conclusion in the passage.

Notice, too, how “and” tells us that the two ideas are added. “And” and similar

expressions (like “moreover,” “furthermore,” “but,” and “however”) often, but not

always, indicate that two ideas are dependent reasons.

Philosophy addresses the most interesting questions that there are.

Philosophy addresses questions that can’t

be answered using standard empirical

methods.

Questions that can’t be answered

using standard empirical methods

are always the most interesting.

5

+

5) “Since philosophy cultivates the use of reason, studying philosophy helps us to

excel in many other areas. Therefore, studying philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor.

Besides, philosophy addresses the most interesting questions that there are. After

all, philosophy addresses questions that can’t be answered using standard empirical

methods and questions that can’t be answered using standard empirical methods are

always the most interesting.”

Notice how “since,” “therefore,” and “after all,” help us to see where the inferences

are. Notice how “and” signals dependent reasons. And notice how “besides” serves to

separate the independent lines of reasoning.

Studying philosophy helps us to excel in

man

y

other areas.

Studying philosophy is a worthwhile endeavor.

Philosophy cultivates the use of reason.

Philosophy addresses the most interesting

questions that there are.

Philosophy addresses

questions that can’t

be answered using

standard empirical

methods.

Questions that can’t

be answered using

standard empirical

methods are always

the most interesting.

6

6) “The nature of philosophy is itself a philosophical question, but I think of

philosophy as the activity of considering questions that can’t be answered empirically

(that is to say, questions that can’t be answered by observation or experiment) and

addressing these questions by thinking rationally, or by employing the sort of critical

thinking skills we’re studying here. The nonempirical questions examined by philosophy

fall into three main categories: 1) epistemology, which considers questions about

knowledge, 2) metaphysics, which considers questions about the ultimate nature of

reality, and 3) value theory, which considers questions about nature of good and bad

as those concepts are invoked in various contexts. The following passages will

introduce you to some of the issues addressed by each branch of philosophy.”

I don’t think that this passage tries to convince us of anything by advancing other

ideas as evidence, so I don’t think that this passage contains an argument.

7

Epistemology

Directions: For each of the following passages, determine whether or not it contains

an argument. If a passage does contain an argument, diagram it, evaluate the

premises, evaluate the inferences, and evaluate the argument as a whole. (Note:

Because these arguments concern fairly abstract material, reasonable people might

disagree about their evaluations.)

7) “Knowledge - as philosophers usually use the term - is justified, true, belief. A

belief is justified if we have good reason to believe it. Beliefs that have some

empirical or rational support, for example, are probably justified. Beliefs that we hold

simply out of fear or superstition, probably aren’t. A belief is true if it corresponds

to reality. My belief that that the earth is nearer to the moon than it is to the sun,

for example, is true if and only if the earth is nearer to the moon than it is to the

sun.”

This passage doesn’t contain an argument because it isn’t trying to convince us of

something by advancing other ideas as evidence. It simply introduces us to

philosophy’s concept of knowledge.

8

8) “Do you know for certain that the objects you see around you are really there? For

all you know, you could be hallucinating every aspect of your experience so you can’t

be certain that anything really exists.”

Notice how the first sentence isn’t important because it doesn’t help to establish the

ultimate conclusion, and notice how the conclusion indicator word “so” helps us to

identify the inference.

This is a version of the argument advanced by René Descartes in Meditation I

of his

Meditations on First Philosophy

.

I think that the inference is pretty good. If one of our beliefs

could

be false

then we can’t be

certain

that it’s true, and if we could be hallucinating everything

then it could be the case that everything around us mere appearance. It could be the

case that nothing exists, and so we can’t be certain that anything does exist.

But what about the premise? Is it true that, for all you know, you could be

hallucinating every aspect of your experience? The following argument attempts to

demonstrate that this premise is false. Let’s see if it works.

For all you know, you could be hallucinating every aspect of your experience.

You can’t be certain that anything really exists.

9

9) “Don’t be silly. I know that I’m not hallucinating every aspect of my experience

because the people around me say I’m not hallucinating.”

Notice how the first sentence isn’t important because it doesn’t help to establish the

ultimate conclusion, and notice how the reason indicator word “because” helps us to

identify the inference.

This argument is seriously flawed, but the flaw (although serious) can be hard

to spot. Can you see what’s wrong?

The problem isn’t with the inference, although it’s easy to think that this is

where the problem lies because it’s easy to think something like, “Okay. Maybe the

people around me say I’m not hallucinating, but who says they’re right? Maybe they’re

mistaken or lying.” The problem with this objection is that although people can be

mistaken or deceptive, we don’t need to worry about trusting what these other people

say in this particular case. The fact that these people

exist

, mistaken or not, is

enough to show that you’re not hallucinating everything. After all, you’re not

hallucinating

them

.

Now do you see what’s wrong with this argument? The problem rests with the

premise. Is it true? Probably. Could people who don’t already believe the ultimate

conclusion believe it? Probably not. People who don’t already believe that they’re not

hallucinating every aspect of their experience must think that they might be

hallucinating every aspect of their experience. Such individuals won’t be sure that

there

are

other people around them; maybe what appear to be other people are simply

hallucinations.

This premise assumes the conclusion. This argument is circular. Can you think

of a noncircular argument for the same conclusion?

The people around me say I’m not hallucinating.

I know that I’m not hallucinating every aspect of my experience.

10

Metaphysics

Directions: For each of the following passages, determine whether or not it contains

an argument. If a passage does contain an argument, diagram it, evaluate the

premises, evaluate the inferences, and evaluate the argument as a whole. (Note:

Because these arguments concern fairly abstract material, reasonable people might

disagree about their evaluations.)

10) “Bad things happen every day, so there can’t be an all-good, all-powerful being in

charge of the universe. Therefore God doesn’t exist. Of course, it’s probably useless

to try to convince devout theists of this.”

Notice how the last sentence isn’t important because it doesn’t help to establish the

ultimate conclusion, and notice how the conclusion indicator words “so” and

“therefore” help us to identify the inferences.

I think that the premise is fine because I think that it’s true and acceptable to

people who don’t already believe that God doesn’t exist.

I also think that the inference from the subconclusion to the ultimate

conclusion is fine because it seems to me that if people believe the subconclusion, it’s

reasonable for them to believe the ultimate conclusion on that basis.

However, I don’t think that the inference from the premise to the

subconclusion is sufficiently strong. Because an all-good, all-powerful being might

have good reason to allow bad things to happen, someone could believe the premise

without believing the subconclusion.

The fact that the inference from the premise to the subconclusion is weak is

enough to make this argument bad.

By the way, this argument is a fairly basic version of the Problem of Evil. More

developed versions of the Problem of Evil attempt to circumvent my criticism by

arguing that a God-like being can’t have a good reason for allowing bad things to

happen.

There can’t be an all-good, all-powerful being in charge of the universe.

God doesn’t exist.

Bad things happen every day.

11

11) “It’s a fact of life that I’m sure you’ve noticed: People who believe in God usually

keep on believing in God and people who don’t believe in God usually keep on not

believing. People who are Christian usually stay Christian and people who are Buddhist

usually remain Buddhist. Have you ever wondered why religious beliefs are so

incredibly hard to change? I think that religious beliefs are hard to change because

such beliefs are usually very important to people, constituting an essential part of

their identity. Such beliefs tend to be very resistant to modification.”

This one is tricky. It might

look

like this is an argument for the conclusion “religious

beliefs are hard to change.” But look again. Is this passage trying to convince us that

religious beliefs are hard to change? Not really. This passage

presupposes

that

religious beliefs are hard to change – it assumes that we already accept this – and it

goes on to

explain why

this is the case. That makes this passage an explanation, not an

argument.

In order to distinguish arguments from explanations, identify the “target” of

the passage. In this case, the target is “religious beliefs are hard to change.” Then

ask, “Is this passage trying to convince me that this idea is true, or does it assume

that I already accept that this idea is true and simply attempt to account for why

things are this way?” If the passage is trying to convince you of the target, it’s an

argument. If the passage is simply trying to account for why the target is true, it’s an

explanation.

12

12) “Many people are tormented by theological doubts, but they needn’t be. It’s clear

that God exists. After all, things in the universe must have been designed by an

intelligent agent because they exhibit an impressive degree of organization.”

Notice how the first sentence isn’t important because it doesn’t help to establish the

ultimate conclusion, and notice how the reason indicator expressions “after all” and

“because” help us to identify the inferences.

I think that the premise is fine because I think that it’s true and acceptable to

people who don’t already believe that God exists.

I also think that the inference from the subconclusion to the ultimate

conclusion is fine because it seems to me that if people believe the subconclusion, it’s

reasonable for them to believe the ultimate conclusion on that basis.

However, I don’t think that the inference from the premise to the

subconclusion is sufficiently strong. Because there are other viable explanations for

the organization mentioned in the premise – evolution by natural selection, for

example – someone could believe the premise without believing the subconclusion.

The fact that the inference from the premise to the subconclusion is weak is

enough to make this argument bad.

By the way, this argument is a fairly weak version of the Teleological Argument

(also known as “The Argument from Design”) for God’s existence. Some versions of

the Teleological Argument aren’t as susceptible to my criticism of the first

inference, because more sophisticated teleological arguments assume that evolution

by natural selection is basically true and maintain that God’s existence is the best

explanation for why the universe is “set up” to allow for natural selection.

Things in the universe must have been designed by an intelligent agent.

God exists. (Or “It’s clear that God exists.”)

Things in the universe exhibit an impressive degree of organization.

13

Value Theory

Directions: For each of the following passages, determine whether or not it contains

an argument. If a passage does contain an argument, diagram it, evaluate the

premises, evaluate the inferences, and evaluate the argument as a whole. (Note:

Because these arguments concern fairly abstract material, reasonable people might

disagree about their evaluations.)

13) “Consequentialist theories maintain that an action is ethical if it serves to produce

certain desirable consequences. Utilitarianism, for example, is a consequentialistist

ethical theory according to which an action is ethical if it maximizes happiness (or

minimizes unhappiness) for the greatest number of people. Deontological ethical

theories, in contrast, assert that an action is ethical if it corresponds to the moral

law, regardless of that action’s tendency to produce any particular effects.”

This passage isn’t trying to convince us of anything by advancing evidence for its

truth. It simply introduces us to two schools of ethics.

14

+

14) “What makes some actions right and other actions wrong? Well, ethics should be

guided by empirical facts about human nature, and everybody wants to be happy.

Consequently, an action is ethical if it produces the greatest happiness for the

greatest number of people.”

Notice how the first sentence isn’t important because it doesn’t help to establish the

ultimate conclusion. Notice also how the conclusion indicator expression

“consequently” helps us to identify the inference and how “and” connects the

dependent reasons.

This is an argument for a type of utilitarianism. In fact, it’s a simplification of

an argument advanced by Jeremy Bentham, one of the fathers of modern

utilitarianism.

The inference in this argument is very strong, so any criticism must focus on

the premises. I think both premises can be challenged. How might you object to the

premise that ethics should be guided by empirical facts about human nature? How

might you object to the premise that everybody wants to be happy? Which premise

do you think is more vulnerable to criticism?

An action is ethical if it produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

Ethics should be guided by empirical

facts about human nature.

Everybody wants to be happy.

15

+

15) “Utilitarianism can’t be right because if it were correct then it would be ethical to

kill one innocent person who isn’t making people happy in order to save ten others who

are making people happy. But clearly it’s never ethical to kill an innocent person.”

Notice how the reason indicator expression “because” helps us to identify the

inference and how “but” connects the dependent reasons.

This criticism of utilitarianism has a strong inference. (In fact, this inference

is valid. If the premises are true then the conclusion

must

be true.) Consequently, if

this argument is bad it must fail at one or both of the premises. What do you think

about them? Do you think that it’s always unethical to kill an innocent person? What

about the claim that if utilitarianism were correct then it would be ethical to kill one

innocent person who isn’t making people happy in order to save ten others who are

making people happy?

Actually, the premise “if utilitarianism were correct then it would be ethical to

kill one innocent person who isn’t making people happy in order to save ten others who

are making people happy” probably only applies to one type of utilitarianism – act

utilitarianism – which says that an action is ethical if

it

serves to maximize happiness.

Other types of utilitarianism are a bit more complex. Rule utilitarianism, for

example, says that an action is ethical if it is of a

type

that would maximize happiness

if

generally practiced

. See the difference? Maybe

one particular

killing of one

innocent person would maximize happiness (the morality of that killing aside), but

what about the

general practice

of killing innocent people in order to maximize

happiness? I suspect that this practice would rapidly cultivate an atmosphere of fear

and paranoia, as everyone wonders if they’ll be killed next. Consequently, rule

utilitarianism would maintain that killing one innocent person in order to save then

others would

not

be ethical.

Utilitarianism can’t be right.

If utilitarianism were correct then it would

be ethical to kill one innocent person who

isn’t making people happy in order to save

ten others who are making people happy.

It’s never ethical to kill an

innocent person.

16

Worldviews

Directions: For each of the following passages, determine whether or not it contains

an argument. If a passage does contain an argument, diagram it, evaluate the

premises, evaluate the inferences, and evaluate the argument as a whole. (Note:

Because these arguments concern fairly abstract material, reasonable people might

disagree about their evaluations.)

16) “Our worldview is our fundamental perspective on reality and is defined by our

epistemological, metaphysical, and value-theoretical assumptions. We all have a

worldview, and it’s important to be aware of the worldview that we have. For one

thing, such an awareness makes it possible for us to adjust our worldviews if we so

choose. For another thing, awareness of our own worldview helps us to better

understand the worldviews that other people have.”

Notice that the first sentence isn’t important because it doesn’t give us reason to

believe the ultimate conclusion - although by defining the terms used in the argument

it does help us to understand the ultimate conclusion. Notice also that “for one thing”

and “for another thing” help us to identify the lines of reasoning. And finally notice

that there are no conclusion or reason indicator expressions to help us identify the

inferences. (Sometimes there aren’t.)

I think that both lines of reasoning are good. Of course, that might be what

you’d expect. After all, I’m a philosopher. Worldview examination is a highly

philosophical activity, so isn’t my assessment of this argument necessarily biased?

In general, if someone accepts an ultimate conclusion, should we discount his or

her positive evaluation of the argument? I don’t think so. For one thing, an individual’s

acceptance of the ultimate conclusion might be a

result

of that person’s positive

assessment of the argument, and not the other way around. For another thing, even if

the individual has other reasons to accept the ultimate conclusion, it doesn’t follow

that his or her assessment of the argument is in any way contaminated by that

acceptance – although it might be prudent for us to ensure that the evaluation isn’t

biased.

It’s important to be aware of the worldview that we have.

An awareness of the worldview that we

have makes it possible to adjust our

worldview if we so choose.

Awareness of our own worldview

helps us to better understand the

worldviews that other people have.

17

17) “Thinking about your worldview can make you feel frustrated and confused.

Therefore, it’s best not to think about your worldview. In addition, serious reflection

about your own worldview might encourage you to feel arrogantly superior to people

who don’t engage in such philosophical contemplation.”

Notice how the conclusion indicator expression “therefore” corresponds to the

inference on the left, how “in addition” separates the lines of reasoning, and how no

conclusion or reason indicator expression corresponds to the inference on the right.

Although both of these premises might be true, I think that the inferences

are weak. Just because something might make us frustrated and confused, it doesn’t

follow that we shouldn’t do it. Maybe the worst frustration and confusion is

temporary, and will be followed by overwhelming benefits. Similarly, it might be the

case that we should do things that carry with them the risk of arrogance because

self-reflective and emotionally mature people are usually able to combat that risk and

because a sense of superiority is often temporary anyway, easily (and sometimes

painfully) punctured by evidence that other people are seldom as stupid or

unobservant as arrogant individuals might think.

But what about people who seem to be arrogant for years on end? Common

wisdom has it that these people are basically insecure and that what appears to be

arrogance is actually posturing designed to help them feel better about themselves.

Do you agree? I honestly don’t know, but I do know that whenever I’m tempted to

show off, it’s because I’m feeling threatened or inferior. When I feel basically good

about myself, I don’t need to be right all the time or try to convince people that I’m

brilliant by using big words when smaller words would be clearer or by dismissing

other people’s thoughts as though they were beneath contempt. Because “apparent

arrogance is often a sign of insecurity” is true of me, and because I assume that I’m

basically similar to other people, I conclude that it’s true of other people as well. (Can

you diagram that argument?)

It’s best not to think about your worldview.

Thinking about your worldview

can make you feel frustrated

and confused.

Serious reflection about your own worldview might

encourage you to feel arrogantly superior to people

who don’t engage in such philosophical contemplation.

18

18) “So, what is your worldview? Think for a moment about your epistemological

beliefs. How important is it to you that your beliefs be true? Would you rather be

wrong and happy, or right and miserable? What do you think is the most trustworthy

source of belief? Do you tend to trust your senses, or do you think that sensory

evidence is too prone to error? Now reflect upon your metaphysical beliefs. Do you

think that everything is basically physical, or do you believe in some nonphysical

reality? Do you think that all events, including your own future actions, are

predetermined, or do you believe in free will? Finally, think for a bit about your

perspective on ethics. Do you think that morality is simply a matter of human

convention? A function of the tendency of an action to produce happiness? A matter

of correspondence to a transcendental moral law? Now, finally, ask yourself if all of

these beliefs “fit together.” Do your epistemological beliefs comport with your

metaphysical and ethical assumptions, for example? Is your metaphysics consistent

with your ethics and epistemology? Can your theory of ethics accommodate your

metaphysics and epistemology? What can be said in favor of your worldview? What

can be said against it? How would you try to convince someone to share your

worldview? Would you want to?”

This passage isn’t trying to convince us of anything, so it isn’t an argument.

19

+

Who-Done-It

Directions: For each of the following passages, determine whether or not it contains

an argument. If a passage does contain an argument, diagram it, evaluate the

premises, evaluate the inferences, and evaluate the argument as a whole.

(Note: You may assume that all of the premises are factually true.)

19) “Who killed Dr. Andrews? It must have been her nephew, Mr. Green. He stood to

inherit over a million dollars at the doctor’s death and he needed the money because

he has gambling debts. Besides, Dr. Andrews sabotaged Mr. Green’s run for political

office, so he probably hated her.”

I’ve labeled the inferences to make them easier to discuss. Notice how “besides”

serves to separate the lines of reasoning, how the reason indicator word “because”

corresponds to inference B, how “and” connects the dependent reasons, and how the

conclusion indicator expression “so” corresponds to inference “C.”

The primary problem with this argument, it seems to me, is that inferences B

and D are both weak because they assume that if someone had a motive for doing

something then he or she must have done it. But of course, that’s not true.

Mr. Green killed Dr. Andrews.

Mr. Green stood to

inherit over a million

dollars.

Mr. Green needs the

money.

Mr. Green has

gambling debts.

Dr Andrews sabotaged

Mr. Green’s run for

political office.

Mr. Green probably

hated Dr. Andrews.

D

C

B

A

20

20) “Haven’t you heard to the story? Just as Mr. Green was ahead in the polls, almost

certain to be elected mayor, Dr. Andrews went to the papers about his gambling

problem. It was front-page news for days, and of course Mr. Green’s campaign was a

lost cause after that. Naturally, there was extensive speculation about why Dr.

Andrews would have behaved so treacherously toward her own nephew, but I think

that she was simply being civic-minded. Dr. Andrews went to the paper because she

honestly believed that Mr. Green would have been a disastrous mayor.”

This isn’t it argument because it doesn’t try to convince us of anything. It does,

however, offer an explanation for Dr. Andrews’ behavior.

21

+

+

21) “Dr. Andrews was poisoned by a little-known and highly-volatile substance.

Consequently, her assassin must have possessed a fairly sophisticated knowledge of

chemistry. Mr. Green, however, has very limited chemical knowledge, so he couldn’t

possibly be the murderer. Additionally, the poison was added to Dr. Andrews’ after-

dinner tea, which proves that whoever killed Dr. Andrews must have been with her in

her home that evening. Mr. Green was attending a law-school reunion over two

hundred miles away from Dr. Andrews’ residence.”

Once again, I’ve labeled the inferences to make them easier to discuss. Notice how

“additionally” serves to separate the lines of reasoning, how the conclusion indicator

word “consequently” corresponds to inference A, how the conclusion indicator word

“so” corresponds to inference B, and how the conclusion indicator expression “which

proves that” corresponds to inference C.

I actually think that this argument is pretty good (assuming, for the sake of

discussion, that the premises are true). And because I think that this argument is

good, I believe the conclusion and am prepared to vindicate Mr. Green.

Mr. Green didn’t kill Dr. Andrews.

Dr. Andrews was

poisoned by a little

known and highly

volatile substance.

Her assassin must

have possessed a

fairly

sophisticated

knowledge of

chemistr

y

.

Mr. Green has

very limited

chemical

knowledge.

The poison was

added to Dr.

Andrews’ after-

dinner tea.

Whoever killed

Dr. Andrews must

have been with

her in her home

that evening.

Mr. Green was

attending a law-

school reunion

over two hundred

miles away from

Dr. Andrews’

residence.

A

B

C

D

22

Argument Construction

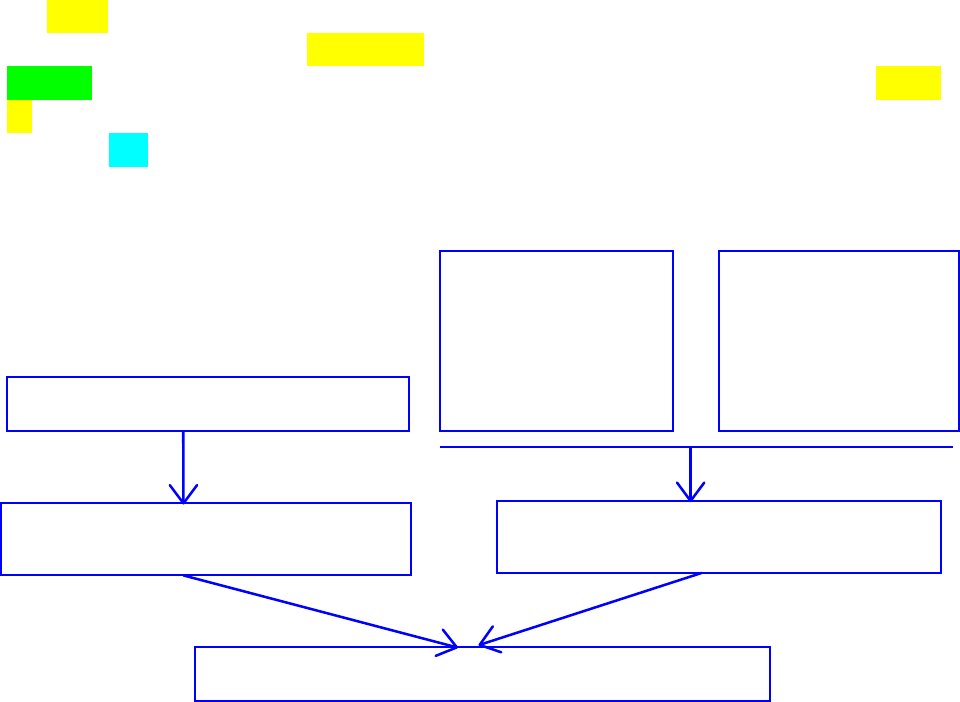

Directions: Answer the following questions to fill in the boxes in the diagram on the

next page.

22) Let’s consider the question “Do parrots make good pets?” The answers will be:

“Parrots make good pets,” and “Parrots don’t make good pets.” Choose one of these

answers. (It doesn’t need to be the answer you really believe.) This will be your

ultimate conclusion. Write your ultimate conclusion in the box labeled “U”. (I know

this isn’t a particularly “deep” subject. Sometimes fairly concrete issues are the best

for practicing argument construction.)

23) Think of

one

reason to believe your ultimate conclusion. It doesn’t need to be a

reason you really believe, but it should be something such that if someone

did

believe

it, he’d be rather likely – although probably not compelled - to believe your ultimate

conclusion. Write that in the box labeled “S.”

24) Now look what your wrote in the box labeled “S,” and think of one reason to

believe

that

. (Don’t even

look

at your ultimate conclusion right now. Look only at your

S. Pretend that your U isn’t even there.) Again, it doesn’t need to be a reason you

believe, but it should be something such that that if someone

did

believe it, she’d be

rather likely – although probably not compelled – to believe S. Write that in the box

labeled “P1.”

25) Now look at the inference between S and U. (Don’t look at your P1. Forget about

your P1. Act like P1 isn’t there.) If someone believed S, what else would she need to

believe in order to be

forced

to believe U? Write that in the box labeled “P2.”

26) Now look at what you’ve written. What’s the “theme” of your argument so far?

Are you talking about companionship, for example? Cost? Think of one reason to

believe your ultimate conclusion that has a completely different theme. Again, it

doesn’t need to be anything you actually believe. Write that in the box labeled “P3.”

23

27) Write a passage containing this argument by filling in your ideas in the following

template: “P1 so S. And P2. Therefore U. Besides, P3.”

“Parrots can talk so parrots can entertain you. And animals that can entertain you

make good pets. Therefore parrots make good pets. Besides, parrots don’t need to go

on walks.”

P3. Parrots don’t need to

go on walks.

P1. Parrots can talk.

P2. Animals that

can entertain you

make good pets.

S. Parrots can

entertain you.

U. Parrots make good pets.

+

24

Real Life

Congratulations! You’ve had a reasonable amount of practice recognizing, analyzing,

evaluating, and constructing arguments. Now you can try your skills in the “real world.”

Two factors that can make argument analysis and evaluation difficult are

length and abstraction.

I’d recommend starting with small arguments of one or two paragraphs

concerning reasonably concrete matters (current events, etc.). Letters to the editor

are good places to look.

When you feel reasonably confident, work your way up to arguments presented

in a page or two, but don’t look at material that’s too abstract yet. Unless you’re

studying philosophy or theology, I’d steer away from those arguments for a bit. Look

for articles in magazines and newspapers.

After you’re comfortable analyzing and evaluating the arguments conveyed in

multiple pages in newspaper or magazine articles, feel free to branch out to more

abstract content. Take on Plato, or the free-will debate. But if you find yourself

getting frustrated, go back to simpler, more concrete arguments for a bit. This will

reassure you that the problems you face stem from the difficulty of the material

you’re studying and not from any lack of technical skill on your part.

Have fun!