Working Paper No. 352

Crop Insurance in India:

Key Issues and Way Forward

Ashok Gulati

Prerna Terway

Siraj Hussain

February 2018

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH ON INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC RELATIONS

Table of Contents

List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................ i

Acknowledgement .................................................................................................................. iii

Abstract .................................................................................................................................... iv

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. v

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1

2. Evolution of Crop Insurance Schemes in India .............................................................. 4

2.1 Crop Insurance in India – The beginning ............................................................................ 4

2.2 Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) - Kharif 2016 onwards ............................. 4

3. Evaluation of the Performance of crop insurance schemes ........................................... 5

3.1 Rolling out PMFBY: Experience of Kharif 2016 and Rabi 2016-17 ................................... 7

3.2 Challenges in the Implementation of PMFBY ................................................................... 13

4. Learning from International Best Practices .................................................................. 20

4.1 Crop Insurance in USA ...................................................................................................... 20

4.1.1 Farm bill 2014 ......................................................................................................... 21

4.2 Crop Insurance in China ................................................................................................... 22

4.2.1 Government Support in Agriculture Insurance ....................................................... 24

4.2.2 Agriculture Reinsurance .......................................................................................... 24

4.2.3 AIR Worldwide ........................................................................................................ 24

4.3 Crop Insurance in Kenya- Kilimo Salama ......................................................................... 25

4.3.1 Progress of the scheme ............................................................................................ 26

4.4 Lessons for India ................................................................................................................ 26

5. Role of Technology in Crop Insurance .......................................................................... 27

5.1 Application of Satellites in Agriculture.............................................................................. 27

5.2 Application of Drones in Agriculture ................................................................................ 28

5.3 Low Earth Orbits (LEO) .................................................................................................... 29

5.3.1 Planet Labs .............................................................................................................. 30

5.4 Government of India’s Programmes of use of Satellite Data for Agriculture ................... 30

5.5 Remote sensing-based Information and Insurance for Crops in Emerging

Economies (RIICE) ............................................................................................................ 30

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations ................................................................... 31

References ............................................................................................................................... 39

Annexures ............................................................................................................................... 41

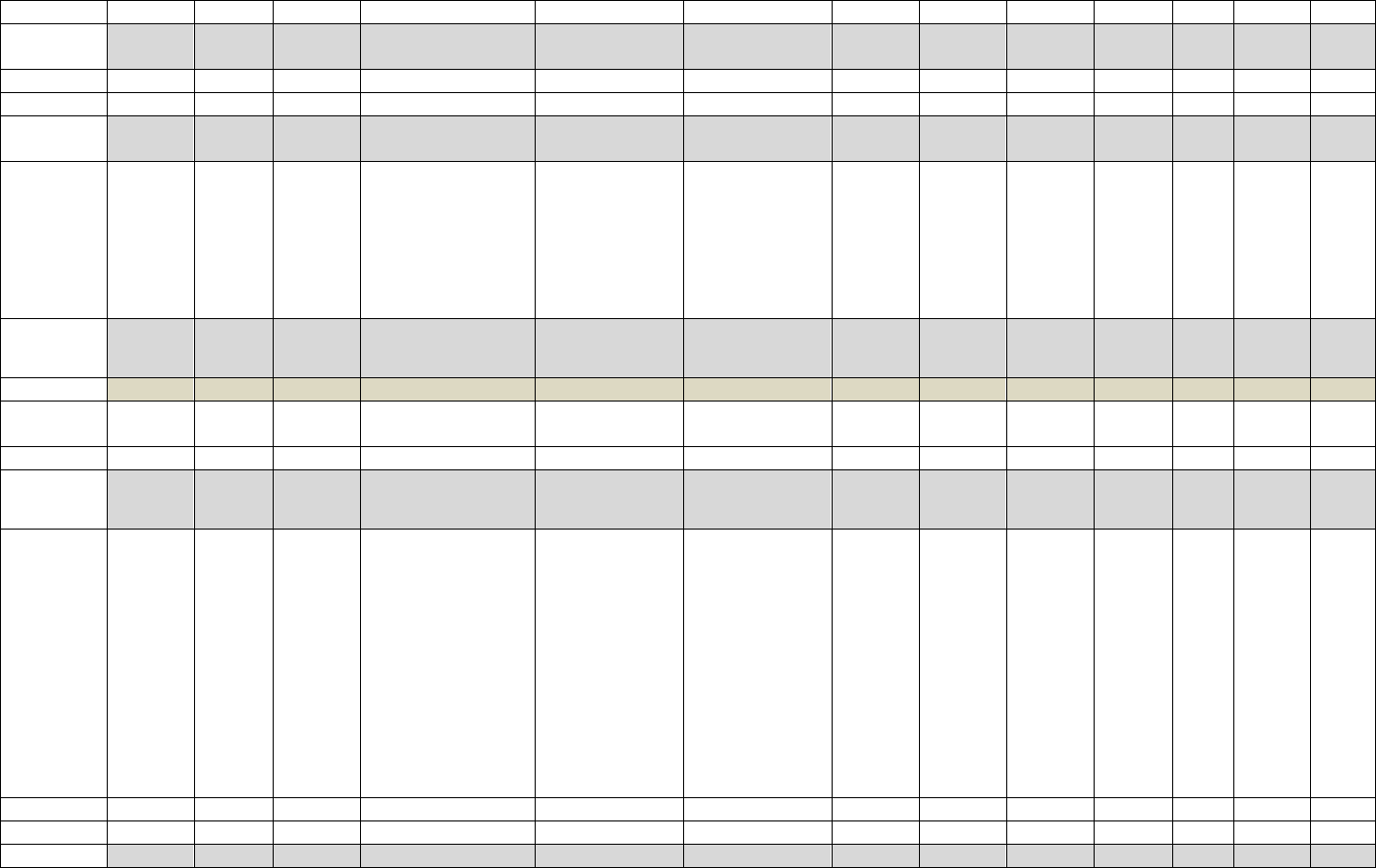

List of Tables

Table 1a: Farmers Covered (million) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2013 to Kharif 2016) ............................................................................... 8

Table 1b: Farmers Covered (million) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Rabi 2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17) .......................................................................... 8

Table 2a: Area Insured (million ha.) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2012 to Kharif 2016) ............................................................................... 9

Table 2b: Area Insured (million ha.) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Rabi

2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17) .................................................................................. 10

Table 3a: Gross Premium (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2012 to Kharif 2016) ............................................................................. 11

Table 3b: Gross Premium (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Rabi

2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17) .................................................................................. 11

Table 4a: Sum Insured (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Kharif

2013 to Kharif 2016) ......................................................................................... 12

Table 4b: Sum Insured (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Rabi

2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17) .................................................................................. 12

Table 5a: Sum Insured (Rs) per hectare under NAIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Kharif

2012 to Kharif 2016) ......................................................................................... 12

Table 5b: Sum Insured (Rs) per hectare under NAIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Rabi

2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17) .................................................................................. 13

Table 6a: Gross Premium as a Percentage of Sum Insured (Kharif 2012 to Kharif

2016) .................................................................................................................. 13

Table 6b: Gross Premium as a percentage of Sum insured (Rabi 2012-13 to Rabi 2016-

17) ...................................................................................................................... 13

Table 7: Comparison between NAIS, MNAIS and PMFBYs ......................................... 18

Table 8: Area Insured and Premiums paid by the Government (USA) ........................... 21

Table 9: Premium Subsidy given by the Central and Provincial Government ................ 24

List of Figures

Figure 1: Average Annual Growth Rate (%) and Coefficient of Variation of GSDP

Agriculture (2005-06 to 2014-15) ............................................................................ 2

Figure 2: Total Premium Paid and Claims Received from Agriculture Insurance (2001-

2013) ...................................................................................................................... 23

Figure 3: Representation of Replanting Guarantee ............................................................... 26

Figure 4: Area under Crop Insurance in India, China and USA ........................................... 32

Figure 5: Gross Premium and Sum Insured (all schemes combined) under Crop Insurance ..... 34

i

List of Abbreviations

ADWDRS Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme

AIC Agriculture Insurance Company of India Limited

ARC Agriculture Risk Coverage

AWS Automatic Weather Stations

CCIS Comprehensive Crop Insurance Scheme

CCE Crop Cutting Experiment

CHAMAN Coordinated Horticulture Assessment and Management using geo

informatics

CPIS Coconut Palm Insurance Scheme

DACFW Department of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare, GoI

DLTC District Level Technical Committee

ESA European Space Agency

FAA Federal Aviation Administration

FCIC Federal Crop Insurance Corporation

FCIP Federal Crop Insurance Program

FCOS Food Crops and Oilseeds

FIIS Farm Income Insurance Scheme

F&V Fruits and Vegetables

GPS Global Positioning System

GoI Government of India

IA Implementing Agency

IASRI Indian Agricultural Statistical Research Institute

ISRO Indian Space Research Organisation

IRDA Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority

ii

LEO Low Earth Orbits

MNAIS Modified National Agriculture Insurance Scheme

MSP Minimum Support Price

MPCI Multiple Peril Crop Insurance

NAIS National Agriculture Insurance Scheme

NCIP Nation Crop Insurance Programme

NADAMS National Agricultural Drought Assessment and Monitoring System

NSSO National Sample Survey Organisation

PCICC Peoples Crop Insurance Company of China

PLC Price Loss Coverage

PMFBY Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana

RIICE Remote sensing-based Information and Insurance for Crops in

Emerging economies

RMA Risk Management Agency

RST Remote Sensing Technology

RUA Reference Unit Area

RWBCIS Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme

RWS Reference Weather Station

SLCCCI State Level Co-ordination Committee on Crop Insurance

SFSA Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture

SoF Scale of Finance

STAX Stacked Income Protection Plan

UAV Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

WBCIS Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme

iii

Acknowledgement

The research leading to this paper was undertaken at ICRIER as a part of the project

“Supporting Indian Farms the Smart Way: Rationalising Subsidies and Investments for

Faster, Inclusive and Sustainable Growth". The project is supported by Syngenta

Foundation to which we are grateful. We would like to thank Dr. Marco Ferroni, Dr. Yuan

Zhou, and Baskar Reddy, of Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture for their

detailed and very useful comments.

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable comments from officers of various

insurance companies, Dr. Ashish Kumar Bhutani, Joint Secretary (Credit and Cooperation),

Government of India, Dr. Shibendu S. Ray, Director of Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast

Centre, Scott Sindelar, former Minister Counselor, U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S.

Embassy in India, Rajeev Chawla, Additional Chief Secretary, Karnataka and Vinod Kumar

Singh, Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Uttar Pradesh.

Our special thanks are due to Prof. Anwarul Hoda, Chair Professor of ICRIER’s Trade Policy

and WTO Research Programme and Mr Umesh Mongia, Associate Vice President at ICICI

Lombard General Insurance Company Limited for their helpful comments and suggestions to

improve the paper.

Needless to say, the authors are fully responsible for the analysis carried out and views

expressed in the paper.

iv

Abstract

Farmers in India are exposed to large agriculture risks due to vagaries of nature. One of the

most effective mechanisms to mitigate agricultural risks is to have a robust insurance system.

Although crop insurance has been in the country since 1972, yet it has been beset with

several problems such as lack of transparency, high premium, delay in conducting crop

cutting experiments and non-payment/delayed payment of claims to farmers. Realizing the

limitations of existing system of crop insurance, a new crop insurance scheme was launched

on Baisakhi day, Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY), from Kharif 2016. Although

the overall area insured has increased by a modest 6.5 percent (from 53.7 million ha in 2015-

16 to 57.2 million ha in 2016-17), the number of farmers insured has increased by 20.4

percent (from 47.5 million to 57.2 million), the sum insured has increased by 74 percent

(from Rs 115432.4 crore to 200618.9 crore), and premium paid has increased by 298 percent

(from Rs 5491.3 crore to Rs 21882 crore) over the same period. The scheme has faced

several challenges during its first year of implementation which pertain to extension of cut off

dates for registration resulting in high premium rates; delay in submission of yield data to

assess damages as the system relies on thousands of Crop Cutting Experiments (CCE); lack

of trust in the quality of such data as they are not being video recorded and delay in payment

of premium subsidy by the state governments to the insurance companies, etc. The litmus test

of any crop insurance program is quick assessment of crop damages and payment of claims

into farmers’ accounts directly, and from that point of view, the first year of implementation

of PMFBY has not been very successful.

This paper recommends use of high technology and JAM trinity by linking land records of

farmers with their Aadhaar numbers and bank accounts for assessment and faster settlement

of claims. A portal linking Core Banking Solution (CBS) and crop insurance is need of the

hour giving information on real time basis. India’s prowess in Information Technology

should come handy to achieve this.

_________

Keywords: Agricultural Risk, Crop Insurance, India, Premium Subsidy

JEL Classification: Q18, G22, G32

Authors’ email: [email protected]; agulat[email protected]; [email protected];

shussain@icrier.res.in

________

Disclaimer: Opinions and recommendations in the report are exclusively of the author(s) and not of any other

individual or institution including ICRIER. This report has been prepared in good faith on the basis of

information available at the date of publication. All interactions and transactions with industry sponsors and

their representatives have been transparent and conducted in an open, honest and independent manner as

enshrined in ICRIER Memorandum of Association. ICRIER does not accept any corporate funding that comes

with a mandated research area which is not in line with ICRIER’s research agenda. The corporate funding of

an ICRIER activity does not, in any way, imply ICRIER’s endorsement of the views of the sponsoring

organization or its products or policies. ICRIER does not conduct research that is focused on any specific

product or service provided by the corporate sponsor.

v

Executive Summary

Farmers are often exposed to natural vagaries, which adversely affect their agricultural

production and farm incomes. One of the most effective mechanisms to mitigate agricultural

risks emanating from natural calamities is adoption of a robust insurance system. Although

crop insurance has been in the country since 1972, yet it has been beset with several problems

such as lack of transparency and non-payment/delayed payment to farmers. Therefore, it

would be important to streamline its operation by developing an institutional mechanism that

can bring greater transparency and effective implementation, particularly in terms of quick

and accurate compensation to farmers for the damages incurred.

Until recently (till March 2016), there were three crop insurance schemes operating in India –

National Agriculture Insurance Scheme (NAIS), Modified National Agriculture Insurance

Scheme (MNAIS) and Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (WBCIS). The penetration of

agricultural insurance was low and stagnant in terms of area insured and farmers covered. In

the three year period from 2013-14 to 2015-16, the average area insured under all the

schemes was 47 million hectare covering 39 million farmers. The high premium rates of 8-10

per cent under MNAIS and WBCIS, delay in settlement of claims, which took around 6 to 12

months, inadequate sum insured and their capping under MNAIS and inadequate government

support in the form of premium subsidies had left a vast majority of farmers without any

significant insurance coverage.

Realizing the limitations of existing system of crop insurance, the GoI launched a new crop

insurance scheme, Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) from Kharif 2016. Some of

the improved features of this scheme are: removal of capping on premium rates leading to

higher amount of sum insured, fixing premium rates at 2 percent in Kharif season and 1.5

percent in Rabi season for farmers, leading to substantial increase in premium subsidy by the

government. The use of mobile based technology, smart Crop Cutting Experiments (CCEs),

digitisation of land record and linking them to farmers' account for faster

assessment/settlement of claims are other steps required for effective implementation of the

new crop insurance scheme.

The analysis done for the new scheme reveals that overall area insured has increased

marginally by 6.5 percent (from 53.7 million ha in 2015-16 to 57.2 million ha in 2016-17).

However, over the same period, the number of farmers insured has increased by 20.4 percent

(from 47.5 million to 57.2 million), the sum insured has increased by 74 percent (from Rs

115432.4 crore to 200618.9 crore), and premiums paid have increased by 298 percent (from

Rs 5491.3 crore to Rs 21882 crore). The government must be complimented for taking bold

decision to increase premium subsidy and scaling up crop insurance.

However, the scheme with a noble intention to protect farmers can succeed only if

operational guidelines are strictly followed and cut off dates are not extended frequently as

was done in Kharif 2016. One of the reasons for high actuarial premium rates quoted by the

reinsurance companies was the extension of cut off dates. Moreover, timely submission of

yield data of CCEs and payment of premium subsidy to insurance companies will smoothen

vi

and fasten the process of claim settlements as done by Tamil Nadu in Rabi 2016-17, Tamil

Nadu when they experienced one of the worst droughts. Unfortunately, even after almost two

years of the implementation of the scheme, mobile devices have not been procured to capture

data of assessment of crop yield for assessment of crop damage. There were allegations of

data manipulations while conducting CCEs like the yield of groundnut of Rajkot district in

Gujarat in Kharif 2016. Karnataka has gone ahead and made compulsory use of mobile

phones while conducting the CCE. They have made Samarakshane portal which provides

information related to CCE claim statements, farmer-wise, including farmer’s Aadhaar

number and account number.

A large scheme like crop insurance takes away almost one-third of financial resources of the

Department of Agriculture Cooperation and Farmers Welfare and it is administered by only

two director level officers in the Ministry. Such a large and important scheme deserves a

dedicated team of professionals which can collate and analyse the data collected from the

states and insurance companies.

This paper draws lessons from some of the best international practices followed by countries

such as China, Kenya and the USA. The heavy premium subsidy programme started by the

Government of China in 2007 led to an expansion of insured farm area from 15 million

hectares in 2007 to 115 million hectares in 2016. In India, total area covered under insurance

in 2016-17 amounts to about 30 percent coverage of gross cropped area, less than half of

what USA (89 percent coverage) and China has achieved (69 percentage coverage). The

premium subsidy payable by the government is 80 per cent and 70 percent in China and

USA, respectively. The Kenyan experience is significant due to its efficiency in settlement of

claims within 2-4 days. Kilimo Salama (Safe Agriculture) is a weather index based insurance

product developed by Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA) in 2009.

They have developed an application that uses Safaricom mobile technology, M-pesa, to

transfer money for payment of claims. Whenever there is a deviation from normal rainfall

resulting in germination failure, the claim amount automatically gets transferred into the

accounts of insured farmers.

This paper recommends widespread use of remote sensing technology in agriculture

insurance programme with minimum human intervention in order to assess crop damages and

expeditious settlement of claims. The application of drones, LEOS, and remote sensing

satellites at fine resolution can prove to be effective in taking images, which could be used to

assess crop damages in an area. Drones could be used to take images of crops affected by

hail, wind, rainfall, etc. Because they fly at lower heights, problems such as cloud obstruction

can be minimised. As soon as there is information on damage in a particular area, they could

be deployed to assess damages in the area so that accurate scenario can be captured

expeditiously. Recently, the world’s largest corn processor Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. in

USA received approval from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to use drones to

gather data on crop insurance claims. China has launched Low Earth Orbits (LEO) to capture

images of vegetation in order to monitor crop growth around the world. Planet Labs, an

vii

organisation based in San Francisco has developed satellites called “doves”. They fly on low

orbit and collect data from any place on earth.

Based on the experience of other countries and rapid advancement in technology, this paper

recommends adoption of modern technology to assess crop damage:

satellite/LEOs/doves/drone/ images, Automatic weather stations and use of mobile-based

technology for crop cutting experiments (CCE). We also suggest conducting high quality

CCEs, switching from random selection of CCE to a science based selection approach on the

basis of satellite technology and gradual transition from CCEs to using technological

solutions for assessment of crop damage. A dedicated constellation of 5 satellites of high

resolution with five day frequency is recommended to increase the precision of crop loss

assessment at village level, which is expected to have an additional cost of Rs 1000 crore to

the exchequer. There is a need to increase the density of Automatic Weather Stations (AWS)

and rainfall data loggers. The entire country could be covered by installing additional 33000

AWS and 170,000 rainfall data loggers; this would cost the government between Rs.300-

Rs.1400 crore, depending on the parameters required for AWS. In order to ensure timely

settlement of claims, the government could make use of the JAM trinity by linking land

records of farmers with their Aadhaar numbers and bank accounts. The use of mobile

technology could be used for smart CCEs and direct submission of crop cutting data to

servers. This can substantially reduce the time taken in compiling reports of crop cutting

experiments from districts. It can also make the process of claim settlement much faster.

We recommend scaling up area insured to 100 million hectares as envisaged in the

operational guidelines of the PMFBY. With more experience of PMFBY and enhanced

competition among state governments to cover larger number of farmers, and as scale of

insurance coverage increases, we hope rates of actuarial premiums will also come down. As

they settle at lower levels (say below 8 percent) than the current ones (12.5 percent), the

Government can think of raising the sum insured from just covering cost of cultivation to

expected levels of income based on last three to five years yields and MSP data.

An increase in awareness among farmers through government agencies, insurance companies

and banks is required. Farmers should be informed through an aggressive media campaign

about compulsory deduction of premium, amount of sum insured, name of insurance

company and the procedure for settlement of claims. IRCTC has already shown the way for

railway tickets booked online by informing the passengers about insurance policy through an

SMS and email. . There is also need to create excitement in this scheme as was done in the

case of the PM’s Suraksha BimaYojana and PM’s Jan DhanYojana.

1

Crop Insurance in India: Key Issues and Way Forward

Ashok Gulati

*

, Prerna Terway

#

, Siraj Hussain

^

1. Introduction

Indian agriculture has little more than half (53 percent) of its area still rain fed. This makes it

highly sensitive to weather conditions, causing uncertainty in agricultural output. Extreme

weather conditions such as floods, droughts, heat waves, cyclones and hailstorms cause

extensive crop damage. Subtle fluctuations in weather during critical phases of crop

development can have a substantial impact on yields. Climate change increases agricultural

risk by increasing variability in rainfall, causing water stress, enhancing susceptibility to plant

diseases and pest attack and, more importantly, raising the frequency, intensity and duration

of extreme weather events like droughts, floods, cyclones and storm surges. According to the

fifth report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the average

combined land and ocean surface temperature data has shown an increase of 0.85°C over the

period 1880 to 2012. Climate change will be particularly hard on agricultural production in

Africa and Asia. For wheat, rice and maize in tropical and temperate regions, climate change

without adaptation is projected to negatively impact production. Therefore, it is necessary for

countries to develop strategies for adaptation to climate changes.

The growth of agriculture in India has varied across states (Figure 1). Variations in the

performance of agricultural growth across states and year to year fluctuations are major

causes for concern for long term food security and also for welfare of farmers. The

coefficient of variation indicates the volatility in agricultural growth rates across various

states. A high coefficient of variation, indicating high volatility is observed in states like

Kerala, Bihar, Rajasthan, Karnataka and Maharashtra.

*

Ashok Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture at ICRIER and former Chairman of the

#

Prerna Terway is a Research Associate at ICRIER; contact email: prernater[email protected]

^

Siraj Hussain is Visiting Senior Fellow at ICRIER and former Secretary, Ministry of Agriculture and

Farmers’ Welfare, GoI; email contact: [email protected]

2

Figure 1: Average Annual Growth Rate (%) and Coefficient of Variation of GSDP

Agriculture (2005-06 to 2014-15)

Source: National Accounts Statistics, CSO

Farmers primarily face two types of risks – yield risk and price risk. An unplanned and major

variation in either the yield or price of a crop in a particular agricultural cycle can translate

into significant losses to the farmer.

Yield risk refers to uncertainty regarding the quantity and quality of agricultural product

harvested at the end of an agricultural cycle. Erratic rainfall distribution has an adverse

impact on agricultural production. On an average, crops on 12 million hectares of land are

damaged annually by natural calamities and adverse seasonal conditions in the country

(Planning Commission, Eleventh Five-year Plan, 2007-2012). In the last fifteen years, there

have been several years when deficiency in rainfall has adversely affected agricultural

production. In 2002, rainfall deficit was 19 per cent due to which there was a loss of 38

million tonnes of food grains. The 2009 drought was the third worst since 1901, when a

rainfall deficit of 18 per cent was recorded and there was a production loss of about 16

million tonnes of food grains.

Price risk refers to the uncertainty about prices that farmers receive for their produce. During

years of high production, prices of crops slide downwards, affecting the incomes of farmers.

There have been times when higher production of crops has led to prices falling to very low

levels, even below MSP levels as happened after the Kharif of 2016 and 2017 in case of

several pulses and oilseeds. Furthermore, farmers have not been adequately protected by

MSPs in all states. Although MSPs are announced by the government for 23 commodities,

they are mainly implemented for rice and wheat and that too in a few states of the country.

The price risk is becoming more pronounced as Indian agriculture opens to global trade. In

2017-18, prices of several agricultural commodities like tur, urad, soybean, groundnut etc

remained much lower than MSP causing widespread distress to farmers in several states.

-12

-7

-2

3

8

13

Madhya Pradesh

Jharkhand

Gujarat

Chattisgarh

Rajasthan

Karnataka

Andhra Pradesh

Assam

Bihar

Odhisha

Haryana

Uttar Pradesh

West Bengal

Uttarakhand

Tamil Nadu

J&K

Maharashtra

Punjab

Himachal Pradesh

Kerala

Growth Rate Coefficent of Variation

3

Income of farmers depends on both prices and yield, which are inversely related to each

other. When aggregate production of a commodity increases, market prices tend to decrease,

and when yields fall, prices generally rise. This offsetting nature of price and production

effects has somewhat cushioning impact on farmers’ incomes.

Traditionally, successive governments have dealt with agricultural distress by relying on the

practice of announcing relief packages from time to time. In 2006, a rehabilitation package of

Rs 16,978.69 crore for farmers in 31 suicide-prone districts in Maharashtra, Kerala,

Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh was approved. The Agricultural Debt Waiver and Debt Relief

Scheme (ADWDRS) was announced in May 2008, which cost the government Rs 52,516.86

crore. Recently, six states-Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka and

Punjab have announced farm-debt waivers and this is expected to spread to other states as

well. Besides these irregular relief packages, the government also provides assistance to

states from the State and National Disaster Response Fund. The cumulative amount released

by the Centre for all calamities including drought and flood from National Disaster Response

Fund between 2011-12 and 2015-16 amount to Rs. 24,055 crore

1

. These ad hoc relief

measures provided by the government, in the wake of natural calamities, are characterised by

severe limitations – lack of transparency in terms of any robust scientific basis for estimating

compensation, non-payment in many cases, inadequate amount of compensation under SDRF

and NDRF and delayed payment to farmers. Therefore, there is urgent need to develop a

robust insurance system to insulate farmers from risks faced by them.

Although agricultural insurance has been present in the country since 1972, it suffers from

operational weaknesses and it has not been able to adequately protect farmers against yield

and price volatility.

This paper evaluates the agriculture insurance schemes that existed in the country before the

PMFBY was introduced in Kharif 2016, how a transition was made to PMFBY and

highlights the major challenges in implementation of PMFBY. Based on this evaluation, and

also a review of how USA, China and Kenya are implementing crop insurance schemes, we

make some recommendations that may help develop a robust crop insurance system in the

country that is transparent, just in terms of sums insured, and quick in settling farmers’ claims

by using high end technology. A particular focus of this paper is on emphasising the role of

technology and experience from some of the best international practices in crop insurance.

Section 2 of the paper deals with various agricultural insurance schemes implemented in the

country since 1985.

Section 3 evaluates the performance of these insurance schemes with a particular focus on the

new crop insurance scheme – PMFBY for Kharif 2016 and Rabi 2016-17.

Section 4 highlights some of the best international practices followed by countries such as

USA, China and Kenya.

1

Data source is Lok Sabha Starred Question No. 31 and Question No. 206

4

Section 5 highlights the use of technology in assessment and settlement if crop damage.

Section 6 concludes based on analysis carried out in previous sections and makes some

recommendations with a view to improvise the functioning of PMFBY for the benefit of

millions of farmers, especially small and marginal that dominates the landscape of Indian

peasantry.

2. Evolution of Crop Insurance Schemes in India

2.1 Crop Insurance in India – The beginning

The first nation-wide crop insurance scheme was the Comprehensive Crop Insurance Scheme

(CCIS) introduced in Kharif, 1985-. This scheme was based on an area approach and area

units were identified for the purpose of assessing indemnity. This was replaced by National

Agriculture Insurance Scheme (NAIS) in Rabi 1999-2000, which was further changed to the

Modified National Agricultural Insurance Scheme (MNAIS) during Rabi 2010-11 (Annexure

1). Apart from these schemes, several other pilot projects such as Seed Crop Insurance (1999-

00), Farm Income Insurance Scheme (Rabi 2003-04) and Weather Based Crop Insurance

Scheme (Kharif 2007) were implemented from time to time. In April 2016, Pradhan Mantri

Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) - an area based scheme and Restructured Weather Based Crop

Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) was introduced.

2.2 Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) - Kharif 2016 onwards

Realizing the limitations of existing system of crop insurance that was not able to meet the

needs of farmers, the NDA government announced a new crop insurance program. PMFBY

scheme became operational from Kharif, 2016 with an objective to provide adequate

insurance coverage and financial support to the farmers in the event of crop failure.

Features of the new scheme

(i) Sum Insured- The sum insured is equal to the Scale of Finance (SoF) for that crop as

fixed by District Level Technical Committee. Sum Insured for individual farmer is now

equal to the Scale of Finance per hectare multiplied by area of the notified crop

proposed by the farmer for insurance. The scale of finance takes into account the cost of

cultivation on the basis of land quality, irrigation expenses and facility as well as cost of

fertilizers, seeds and labour which varies from one district to another.

(ii) Premium Rates: The premium rates payable by farmers for Food Crops and Oilseeds

(FCOS) is fixed at 2 percent of the Sum Insured or Actuarial rate, whichever is less, for

Kharif season and 1.5 percent for Rabi season. For commercial/horticulture crops,

premium rate of 5 percent is fixed to be paid by the farmer. The difference between

premium rate and rate of insurance payable by farmers will be shared by the Central

government and the State government equally as premium subsidy.

5

(iii) Estimation of Crop Yield: The minimum number of Crop Cutting Experiments (CCEs)

required at village level is 4 for major crops and 8 for other crops. Inputs from

RST/satellite imagery would also be utilized in optimizing the sample size of CCEs.

(iv) Use of modern technology: The CCEs have been lacking in reliability and speed in

estimation of crop yield. The use of mobile based technology with GPS stamping was

recommended to improve the quality of data and make faster assessment of claims. The

expense in procuring handheld devices/smart phones are to be borne equally by the

Centre and the State, with a cap on total funds to be made available by the Central

government. The use of technology available in the fields of remote sensing, aerial

imagery, satellites etc. would reduce manpower and infrastructure. It is estimated that

using a mix of modern technology can be expected to minimize the number of CCEs by

about 30 percent.

(v) Role of Private players: The public sector company, Agriculture Insurance Company

(AIC) of India along with other public and private insurance companies are

participating in the new crop insurance scheme. The selection of Implementing Agency

(IA) is made by state governments by adopting a cluster approach consisting of 15-20

‘good’ and ‘bad districts’, based on risk profile, with reference to the bid to be laid out.

Selection of IA is to be made through competitive bidding upto 3 years.

(vi) Time frame for loss assessment: The cut-off date for the receipt of yield data is within

one month of final harvest. Processing, approval and payment of final claims is based

on the yield data and it is to be completed within three weeks from receipt of yield data.

(vii) Timely release of premium subsidy to Insurance Companies: The government (both

Central and State) must release 50 percent share of premium subsidy to insurance

companies, in the beginning of every crop season, based on fair estimates submitted by

them, and settle balance of actual premium subsidy for season as soon as final figures

are submitted by insurance company.

(viii) Publicity and awareness: Adequate publicity is to be given in all villages of the notified

districts through fairs, exhibitions, SMS, short films, electronic and print media and

documentaries. The crop insurance portal should be regularly uploaded with all

published material information.

3. Evaluation of the Performance of crop insurance schemes

CCIS covered cereals, pulses and oilseeds. The premium rates were administered uniformly

throughout the country. It was kept at 2 percent for rice, wheat and millet crops and 1 percent

for pulses and oilseeds. It was subsidized by 50 percent for small and marginal farmers.

However, high claim to premium ratio, which was 6.72 for an average of 15 Kharif seasons

(1985-99), and 5.75 for an average of 14 Rabi seasons (1985-86 to 1998-99), made the

scheme financially unviable. The sum insured was to be limited to Rs 10,000 per farmer,

6

irrespective of the size of loan and farm size (Report of the Committee to Review the

Implementation of Crop Insurance Schemes in India, 2014).

This scheme was replaced by NAIS in 1999-2000 which was further modified and renamed

as Modified NAIS during Rabi 2010-11. WBCIS was introduced in 2007.

Some of the limitations of these schemes are as follows:

Low penetration of agricultural insurance

The penetration of agricultural insurance in India was low and stagnant in terms of the area

insured and the number of farmers covered till 2014-15. In the three years period (2013-14 to

2015-16), the average area insured under all the schemes combined was 16.3 million hectares

in the Rabi and 29.7 million hectare in the Kharif. The number of farmers insured was 13

million in the Rabi and 25 million in the Kharif for all the schemes. The primary reason for

low coverage was unaffordable high premium rates and capping of premium and sum assured

under MNAIS. The average premium rate was around 10 per cent for MNAIS and WBCIS.

Premium and sum insured related issues

The sum insured was worked by multiplying the Notional Threshold Yield with MSP/average

farm gate price. However, in MNAIS and WBCIS, premium rates were calculated on

actuarial basis, (which was a departure from the administratively decided premium rate that

prevailed during NAIS) and they were capped in order to reduce total expenditure on

premium subsidy by both Central and state governments. Sum insured per hectare was

reduced to an amount to commensurate with capped premium rates and this led to low sum

insured for most of the crops. As actuarial premium rates under MNAIS were high for most

of the insured crops in many districts, sum insured in certain cases was insufficient to even

cover the cost of cultivation.

Delay in assessment and settlement of claims

The assessment of damage was based on the traditional system of crop cutting experiments

that took 6-12 months. The settlement of claims took unduly long time; at times it extended

beyond the next cropping season.

Area discrepancy

The issue of area discrepancy has been prevalent since early years of crop insurance as in

many cases, area insured was greater as compared to the net sown area as reported by the

government agencies. According to PK Mishra Committee report (2013) this problem was

acute particularly in some districts of Gujarat growing groundnut as major crop. In Kharif

1993, the claim for groundnut alone was Rs 192.96 crore out of a total claim Rs 207.42 crore

for all crops. The problem of area discrepancy continued even after the introduction of NAIS

in Gujarat in Kharif 2000. To solve this problem of fudging of data by state machinery, area

7

correction factor

2

was applied by AIC but the states showed unwillingness to apply such

correction factors.

3.1 Rolling out PMFBY: Experience of Kharif 2016 and Rabi 2016-17

With the new and improved features of PMFBY, overall area insured has increased

marginally by 6.5 percent (from 53.7 million ha in 2015-16 to 57.2 million ha in 2016-17).

However, over the same period, the number of farmers insured has increased by 20.4 percent

(from 47.5 million to 57.2 million), the sum insured has increased by 74 percent (from Rs

1,15,432.4 crores to 2,00,618.9 crores), and premium paid has increased by 298 percent (from

Rs 5,491.3 crores to Rs 21,882 crores). India has definitely taken a leap forward and it

appears that a structural breakthrough has been achieved for which GoI deserves

appreciation. But the use of mobile based technology, smart Crop Cutting Experiments

(CCEs), digitisation of land record and linking them to farmers' account for faster

assessment/settlement of claims are some of the steps that are yet to be fully accomplished

for effective implementation of the new crop insurance scheme.

Farmers Insured

The total number of farmers insured has increased by 20.4 percent (from 47.5 million to 57.2

million between 2015-17 and 2016-17. The new crop insurance scheme has provided

coverage to 38.9 million farmers in Kharif 2016 as compared to 25.4 million farmers in

Kharif 2015, an increase of 53.1 percent (Table 1a). In Rabi 2016-17 the number of insured

farmers insured under PMFBY is 16.2 million, an increase of 17.4 percent from Rabi 2015-

16 (Table 1b). The increase in number of farmers insured is significant in Gujarat, Himachal

Pradesh, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal in Kharif 2016 (Annexure 2). In Rabi

2016-17, total farmers insured (including WBCIS) has increased marginally by 0.6 percent.

The number of insured farmers has declined in a few states like Bihar, Maharashtra and

Rajasthan in Rabi 2016-17 (Annexure 3).

In a communication issued by Public Information Bureau, GoI (dated 7.12.2016)

3

, the

government has claimed that there has been an increase of more than 6 times in the coverage

of non-loanee farmers from 1.49 million in Kharif 2015 to 10.26 million in Kharif 2016,

which shows that the scheme has been well received by the non-loanee segment. However,

figures received from industry show that the number of non-loanee farmers has increased

from 9.87 million in Kharif 2015 to 10.18 million in Kharif 2016, an increase of merely 2.4

percent. According to our discussion with experts, increase in the number of non-loanee

farmers is mainly in Maharashtra where farmers reported as non-loanee have increased from

nil in Kharif 2015 to 7.2 million in Kharif 2016. This is due to a judgement of Bombay High

Court which ruled that loanee farmers cannot be forced to take insurance. Therefore all the

farmers taking insurance are considered non loanee farmers.

2

The area-correction factor is arrived at by dividing the area sown by the area insured for a given unit area,

and applied on the claim amount in order to scale it down. As a result, the claims of all the farmers in a unit

area are scaled down uniformly.

3

http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease

8

According to data from the industry, the PMFBY, like previous schemes, is primarily

covering only loanee farmers as they account for 74 percent of total farmers insured in Kharif

2016 and 79 percent in Rabi 2016-17. However, there is a significant jump in non loanee

farmers in Jharkhand, AP, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. In Gumla Simdea region of

Jharkhand, the State Co-operative Bank has reported that 62,567 non-loanee farmers took

crop insurance for paddy and 11,789 for maize in Kharif 2017.

Table 1a: Farmers Covered (million) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2013 to Kharif 2016)

4

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

Grand Total

% Increase

Kharif 2012

10.7

2.1

12.8

8.1

20.9

Kharif 2013

9.7

2.4

12.1

-5.5

8.9

21.0

0.5

Kharif 2014

9.7

5.9

15.6

28.9

8.2

23.8

13.4

Kharif 2015

20.6

4.8

25.4

62.8

5.4

30.8

29.4

Kharif 2016

(PMFBY)

38.9

38.9

53.1

1.5

40.4

31.2

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Table 1b: Farmers Covered (million) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Rabi 2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

Grand Total

% Increase

Rabi 2012-13

6.1

1

7.1

5.6

12.7

Rabi 2013-14

4

3

7

-1.4

5.3

12.3

-3.1

Rabi 2014-15

7.1

3.2

10.3

128.9

3.1

13.4

8.9

Rabi 2015-16

10.1

3.7

13.8

34.0

2.9

16.7

24.6

Rabi 2016-17

(PMFBY)

16.2

16.2

17.4

0.6

16.8

0.6

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Area Coverage

The total area insured in kharif and rabi taken together has increased only slightly by 6.5

percent (from 53.7 million ha in 2015-16 to 57.2 million ha in 2016-17). The area under the

new scheme has increased from 27.2 million hectare (MNAIS & NAIS combined) in Kharif

2015 to 36.6 million hectare (PMFBY) in Kharif 2016, an increase of 34.6 percent (Table

2a). States registering significant increase in area coverage in Kharif 2016 included Assam,

Gujarat, West Bengal and Uttarakhand (Annexure 4). In Rabi 2016-17, area insured has

shown a marginal decline as compared to Rabi 2015-16.

Area insured under WBCIS has however fallen from 11.1 million hectare in Kharif 2012 to

1.3 million hectare in Kharif 2016, drop of about 88 percent (Table 2a). Our discussions with

experts in the industry reveal the following main reasons for this drastic fall in area insured:

4

All data related to Kharif 2016 and Rabi 2016-17 are updated as on December, 2017

9

High Actuarial Premium Rates

The actuarial rates vary across states. With the removal of capping of premium rates and no

reduction in sum insured, actuarial premium rates have increased in Kharif 2016 compared to

previous years. It increased from 11.6 percent in Kharif 2015 to 12.5 percent in Kharif 2016

(Table 6a). For WBCIS, the actuarial premium rates were as high as 43 percent and 33.5

percent for states like Rajasthan and Maharashtra, respectively, in Kharif 2016 (Annexure 6).

In case of horticulture crops also, actuarial premium rates were at very high levels in Kharif

2016. For example, in case of Maharashtra it varied in the range of 40 percent to 55 percent

for pomegranate and 55 percent to 70 percent for guava.

Faulty Product Design

Our discussions with insurers further revealed that in many cases, there is no correlation

between temperature and other triggers in the weather station and yield calculation.

Whenever there is a temperature trigger, farmers are eligible for compensation even if there is

no reduction in yield. As informed by insurance companies, agriculture departments of states

prepare term sheets but in many cases these are designed in such a manner that it necessarily

triggers a payout. For example, in case of Alwar district in Rajasthan, farmers were eligible

for compensation in case rainfall received was below 300 mm (Annexure 7). Historical data

of this district show that in the past twenty years this amount of rainfall has never been

received. Therefore, insurance companies (aware of almost compulsory payout) quoted high

actuarial rates of 70 percent to recover their losses.

Ethical Issues

The authors were informed by some key stakeholders in the crop insurance chain that there

were cases of unethical practices in some districts by manipulating temperature at the weather

station to cause “trigger”. For example, in Churu district of Rajasthan in 2013 and 2014, there

are allegations that some famers had used ice in the weather station that led to deviation in

actual temperature and they became eligible to receive claims.

Table 2a: Area Insured (million ha.) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2012 to Kharif 2016)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

Grand Total

% Increase

Kharif 2012

15.7

2.2

17.9

11.1

29

Kharif 2013

14.3

2.3

16.6

-7.3

11.2

27.8

-4.1

Kharif 2014

11.6

7.0

18.6

12.0

9.6

28.2

1.4

Kharif 2015

21.7

5.5

27.2

46.2

6.3

33.5

18.8

Kharif 2016

36.6

36.6

34.6

1.3

37.9

13.1

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

10

Table 2b: Area Insured (million ha.) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Rabi 2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

Grand Total

% Increase

Rabi 2012-13

8.7

0.7

9.4

5.9

15.3

Rabi 2013-14

6.5

3.3

9.8

4.3

5.3

15.1

-1.3

Rabi 2014-15

9.3

3.6

12.9

31.6

4.8

17.7

17.2

Rabi 2015-16

11.8

3.5

15.3

18.6

4.9

20.2

14.1

Rabi 2016-17

18.9

18.9

23.5

0.4

19.3

-4.5

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Gross Premium

In MNAIS and WBCIS, the premium rates were capped at 11 per cent and 9 per cent (of sum

insured) for food and oil seeds crops for Kharif and Rabi season respectively. In case of crops

whose premium was higher than the capped level, sum insured was reduced to capped level

whereas actuarial rates continued to apply (Reduction in sum insured was only in case of

MNAIS). It was basically done to reduce the liability of GOI and State Government towards

premium subsidy. In NAIS there was no such restriction on sum insured as the claim itself

was paid by Central and State Government if it exceeded the total premium amount. The

capping resulted in very low sum insured and high premium rate under MNAIS. This issue

has now been resolved in PMFBY. There is no capping on premium rates and sum insured is

now based on the Scale of Finance for the district as decided by district level technical

committee. With the removal of capping on premium rates, sum insured has increased

significantly in few districts. One such example is that of maize crop in Gorakhpur district of

Uttar Pradesh. The actuarial rate for Kharif maize 2015 under MNAIS was 57 percent and the

original sum insured was Rs 8,415/ha. However, as capped premium rate of 11 percent was

applicable, the sum insured was reduced to Rs 1624/ha. With the implementation of the new

scheme, the actuarial rate for maize in the same district in Kharif 2017 went down to 4.22

percent and the sum insured has increased to Rs 12,096/ha.

Under PMFBY, the farmers’ share of premium (as percentage of sum insured) is fixed at 2

percent in Kharif 2016 and farmer's share in gross premium accounts to 17 percent

5

.

Difference between actuarial rate and farmers’ premium is being given as premium subsidy

by GoI and State Government. Thus, farmers are receiving premium subsidy to the extent of

83 percent by the Central and the State government

6

. The government has allocated Rs

13,000 crore in 2018-19 (BE). The expenditure for 2016-17 and 2017-18 (RE) was Rs 11,051

crore and Rs 10,698, respectively. It included the amount required to settle pending claims

under NAIS.

5

In Kharif 2016, the total value of gross premium for Kharif 2016 under PMFBY is Rs 15,488 crore out of

which Rs 2666 crore is borne by farmers.

6

The level of subsidy would differ depending on the actuarial premium discovered through bidding.

11

With the removal of capping on premium rates, there has been a quantum jump in gross

premium (Table 3a and 3b). It has increased by 486.6 percent (for PMFBY) in Kharif 2016

and almost 275.3 percent in Rabi 2016-17.

Table 3a: Gross Premium (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2012 to Kharif 2016)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

%

Increase

WBCIS

Total

%

Increase

Kharif 2012

878

564

1442

1294

2736

Kharif 2013

975

639

1614

11.9

1478

3092

13.0

Kharif 2014

844

928

1772

9.8

1565.5

3337.5

7.9

Kharif 2015

1828

812.4

2640.4

49.0

986.9

3627.3

8.7

Kharif 2016

15488.3

15488.3

486.6

863.2

16351.2

350.8

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Table 3b: Gross Premium (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Rabi 2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

Total

% Increase

Rabi 2012-13

447.6

189

636.6

923.0

1559.6

Rabi 2013-14

297.5

434.8

732.3

-27.6

923.4

1655.7

6.2

Rabi 2014-15

550.6

501.5

1052.1

43.7

556.4

1608.5

-2.9

Rabi 2015-16

716.7

543.8

1260.5

19.8

603.5

1864.0

15.9

Rabi 2016-17

4731.1

4731.1

275.3

798.9

5530

196.7

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Sum Insured

The sum insured for both loanee and non-loanee farmers are equal to the scale of finance as

decided by the District Level Technical Committee (DLTC). For an individual farmer, the

sum insured is equal to the Scale of Finance per hectare multiplied by area of the notified

crop proposed by the farmer for insurance. In NAIS and MNAIS, the sum insured for loanee

farmers was equal to the amount of crop loan sanctioned which was extendable upto the

value of the threshold yield. There are many instances when a State Government fixed sum

insured very low so that the outgo under NAIS for payment of claims was limited and

premium subsidy under MNAIS borne by State Government was not very high.

As compared to Kharif 2015, the total sum insured for all the states has increased from Rs

60,773 crore (MNAIS & NAIS) to Rs 1,24,382 crore (PMFBY) in Kharif 2016, an increase

of about 104.7 percent (Table 4a). The total value of sum insured under PMFBY and

RWBCIS combined has increased by 89.4 percent in Kharif 2016. In Rabi 2016-17 sum

insured has increased by 65.3 percent under PMFBY and 50.3 percent in PMFBY and

RWBCIS (Table 4b).

12

The sum insured per hectare was Rs 33,984 in Kharif 2016 and Rs 34,847 in Rabi 2016-17

(Table 5a and 5b) under PMFBY. However, even under PMFBY farmers are provided

coverage only to the extent of cost of cultivation as estimated by DLTC for arriving at Scale

of Finance (SoF) and not the loss of their prospective incomes. Therefore even though there

is an increase in sum insured per hectare, this amount may still not be adequate to cover a

farmer’s risk of loss of income due to lower market prices. The maximum claim is limited to

cost of cultivation, not loss of prospective income.

Table 4a: Sum Insured (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY

(Kharif 2013 to Kharif 2016)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

% Increase

Kharif 2012

27199

4897

32096

12871

44967

Kharif 2013

28924

5825

34749

8.3

14623

49372

9.8

Kharif 2014

24389

9481

33870

-2.5

13254

47124

-4.6

Kharif 2015

52508

8265

60773

79.4

8533

69306

47.1

Kharif 2016

124382

124382

104.7

6903

131285

89.4

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Table 4b: Sum Insured (Rs crore) under NAIS, WBCIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Rabi

2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

Total

% Increase

WBCIS

Total

% Increase

Rabi 2012-13

15708

2077

17785

10655.5

28440.5

Rabi 2013-14

12549.5

6406.5

18956

6.6

10901.9

29857.9

5

Rabi 2014-15

21512.5

9107.8

30620.3

61.5

4400.4

35020.7

17.3

Rabi 2015-16

27809.6

12022.6

39832.2

30.1

6294.2

46126.4

31.7

Rabi 2016-17

65860.8

65860.8

65.3

3473.1

69333.9

50.3

Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance and Industry data

Table 5a: Sum Insured (Rs) per hectare under NAIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Kharif

2012 to Kharif 2016)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

WBCIS

Kharif 2012

17324

22259

11595

Kharif 2013

20227

25326

13056

Kharif 2014

21025

13544

13806

Kharif 2015

24197

15027

13544

Kharif 2016

33984

53100

Source: Authors' calculations

13

Table 5b: Sum Insured (Rs) per hectare under NAIS, MNAIS and PMFBY (Rabi

2012-13 to Rabi 2016-17)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

WBCIS

Rabi 2012-13

18055

29671

18060

Rabi 2013-14

19307

19414

20570

Rabi 2014-15

23132

25299

9168

Rabi 2015-16

23567

34350

12845

Rabi 2016-17

34847

86828

Source: Authors' calculations

Table 6a: Gross Premium as a Percentage of Sum Insured (Kharif 2012 to Kharif

2016)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

WBCIS

Kharif 2012

3.2

11.5

10.1

Kharif 2013

3.4

11

10.1

Kharif 2014

3.5

9.8

11.8

Kharif 2015

3.5

9.8

11.6

Kharif 2016

12.5

12.1

Source: Authors' calculation

Table 6b: Gross Premium as a percentage of Sum insured (Rabi 2012-13 to Rabi

2016-17)

Season

NAIS

MNAIS

WBCIS

Rabi 2012-13

2.8

9.1

8.7

Rabi 2013-14

2.4

6.8

8.5

Rabi 2014-15

2.6

5.5

12.6

Rabi 2015-16

2.6

4.5

9.6

Rabi 2016-17

7.2

22.7

Source: Authors' calculations

3.2 Challenges in the Implementation of PMFBY

Extension of cut off dates

As Kharif 2016 was the first cropping season of the new scheme, various states claimed that

they faced teething problems in bidding process for selection of the insurance companies for

concerned clusters. After the issue of guidelines by GOI in February 2016, several State

Governments invited bids for discovering actuarial rates for various crops in cluster of

districts. As against the original cut-off date of July 31, mentioned in the operational

guidelines of the scheme, some states requested the Centre for an extension of cut-off date.

Thus, due to delay in carrying out the requisite preliminaries the date of tender submission

was extended to 10

th

August 2016.

14

However, most of the states that floated their tender on time and completed the tender process

were able to receive low actuarial premium rates. For example states like Andhra Pradesh,

West Bengal and Chhattisgarh completed their bidding process in the months of April and

May, 2016. These states were able to receive actuarial rates between 4-9 percent. However,

other states like Bihar, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra were late in opening and

evaluating bids and completed the process only in the months of June and July, 2016 and they

received high actuarial rates of around 20 percent (Annexure 6). Moreover, requests for such

extensions of cut-off dates by State Government in future could lead to the problem of

adverse selection. For example, Bihar encountered excessive rainfall and flood during Kharif

2016. The tender was floated in July, 2016 when the flood situation was already known. As a

result, the companies quoted very high actuarial rate of 17 percent. Moreover, the reinsurance

companies also quoted high reinsurance rates. Similarly, after the demonetisation of Rs 500

and Rs 1000 currency notes was announced by the government, the cut off dates for

enrolment under PMFBY in Rabi 2016-17 was extended to 10th January, 2017 from the

original date of 31st December, 2016.

Actuarial Premium rates and premium subsidy

The gross premium for FY 2016-17 is Rs 21,882 crore (PMFBY and RWBCIS) out of which

famers’ share is Rs 4,373 crore. The remaining premium subsidy is shared by the Central

government and the State government. The share of the Central Government was Rs 6,623

crore in Kharif 2016 and Rs 2,182 crore for Rabi 2016-17. Thus the total amount required for

premium subsidy by the Central government was Rs 8,805 crore in 2016-17. As mentioned

above, there were outstanding bills of NAIS also. Due to increase in premium subsidy in

Kharif 2016, the government revised the amount allocated towards crop insurance to Rs

11,051 crore in FY 2016-17. In 2016-17, the actual expenditure of DACFW on all the

schemes was Rs 36,912 crore out of which Rs 13,397 crore was for interest subvention. Thus

if interest subvention is excluded from department’s budget, premium subsidy on crop

insurance took almost 17 percent of the budget of Department of Agriculture, Cooperation

and Farmers' Welfare

With an increase in area insured it was expected that the actuarial premium rates would go

down. However, gross premium as a share of sum insured increased to 12.5 percent in Kharif,

2016. Although there is an increase in the actuarial premium rates, it must be noted that there

are comparability issues across various insurance schemes. In case of NAIS, premium rates

were administered by the government and in MNAIS they were market determined but

capping on these rates acted as a barrier in real discovery of actuarial premium rates. Under

PMFBY, capping on premium rates was removed and therefore the actuarial rates of 2016-17

can be said to perhaps reflect the risk profile more accurately.

Experts in the industry also informed the authors that high actuarial rates were also caused by

the expansion of reinsurance market. According to them, only 25 percent of risk (as a

percentage of sum insured) is absorbed by the domestic insurance companies. Out of the

remaining 75 percent, 50 percent is absorbed by the domestic reinsurance company (General

Insurance Corporation) and balance 25 percent by foreign reinsurance companies. Some of

15

the major foreign players include Swiss Re, Munich Re, SCOR, Hannover Re and Berkshire

Hathaway. The risk has shifted from insurance companies to the reinsurance companies and

therefore the actuarial premium rates may not come down anytime soon unless the

administration of scheme at the state level improves substantially. Contrary to this statement,

some other experts have suggested that with an increase in area insured to 100 million

hectare, the actuarial premium rates could come down to as low as 3-4 percent. However, as

it appears today, with rather unpredictable ways of implementation of the scheme, reinsurers

don’t have full confidence and therefore premium rates are likely to remain high unless

concerted efforts are made to strictly follow operational guidelines of the scheme so that

reinsurers get the confidence that Indian crop insurance players, including the state

governments would play by the rules. Payment of premium subsidy by government to

insurance companies in time and adherence to cut-off dates are the minimum pre-conditions

to encourage insurance companies to quote lower rates in future.

Inadequate insurance coverage

Sum insured per hectare has increased to Rs 33,984 in Kharif 2016 and Rs 34,847 in Rabi

2016-17 under PMFBY. As PMFBY is yield based, price risk is still not covered and farmers

remain exposed to volatility in prices of agricultural commodities. So, even the new crop

insurance scheme has not been able to cover loss of prospective income of farmers due to

vagaries of market. Sum insured was to be equal to the SoF for that crop as fixed by District

Level Technical Committee. But the data for Kharif 2016 reveals that sum insured in many

districts was way lower than SoF. For example, in Alwar and Dungarpur district in Rajasthan,

SoF for cotton was Rs 58,500 per hectare and Rs 1,50,000 per hectare, respectively against

sum insured of Rs 15,720 and Rs 18,720 per hectare, respectively. This was possibly done as

the state government may have preferred lower sum assured so as to restrict its share of

premium subsidy.

Insufficient and inefficient CCEs

The total number of CCEs planned by the government for both Kharif and Rabi season in

2016-17 was 9.27 lakh. With the CCEs being brought down to village panchayat level, it is

expected that the number of CCEs will go up to 30 lakhs (20 lakhs in Kharif season and 10

lakhs in Rabi season). In the operational guidelines of PMFBY, the use of mobile based

technology with GPS stamping has been mandated to improve the quality of data and make

faster assessment of claims. However, neither the number of CCEs has increased nor have the

State governments in most of the states procured mobile devices to make smart assessment of

crop yield. Our discussions with experts reveal that there were large scale data manipulations

in some cases while conducting CCEs. For example there is egregious case of, Rajkot district

in Gujarat in Kharif 2016 where it is claimed that the yield of groundnut was largely

underestimated which made the insurance companies liable to pay exaggerated claims to

farmers. As informed by experts in the industry, despite bumper harvest of groundnut, the

yield was reported to be 500 kilograms per hectare against actual estimated yield of about

1200 kilograms per hectare. Due to underestimation of crop yield, insurance companies may

become liable to pay huge claims even if there is no actual reduction in yield of crops. This is

16

nothing short of a fraud in the name of crop insurance and brings very bad name to the

implementation failure of PMFBY. It needs to be investigated at the highest level,

responsibility must be fixed and stern action may be initiated against unscrupulous elements.

Only then PMFBY can be salvaged and premiums reduced. Else, we are afraid, it may not

serve its intended purpose. It may be emphasized that if GoI wants PMFBY to succeed, it has

to ensure transparency in conduct of CCE and prevention of malpractices.

Assessment and payment of claims

The state government is responsible for providing yield data of CCEs to insurance companies

and claims are to be settled within three weeks from the date of data receipt. But companies

have not yet paid their claims to farmers and they have cited delay in receiving premium

subsidy from the state government as the main reason for delay settlement on claims. For

instance insurance companies have partially received premium subsidies from states like

Bihar, Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka (Annexure 8). Another reason for delay in this

process is late submission of yield data by states to companies, which extends way beyond

the required date of notification. This is true in case of states like Gujarat and Tamil Nadu in

Kharif 2016 and Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu in Rabi 2016-17 that have partially submitted

yield data to insurance companies.

There have been allegations in media made that insurance companies have made large profits

at the cost of farmers and government as gross premium collected is far greater than claims

paid to farmers. It must be noted that Kharif 2016 was a year of normal monsoon with only 3

percent shortfall at all India level and drought prone regions in Central India received 6

percent above normal rains. In normal rainfall years, it will be common that claim payouts

are likely to remain lower than premiums collected, while in bad years with drought/floods,

etc the claims may even exceed premiums collected. The nature of insurance business has to

be seen over a cycle of about 5 years, which includes good, normal, and bad years to see how

far the premiums collected match with payments made as compensation. The total amount of

claims paid is 2016-17 (PMFBY and RWBCIS) is Rs 12,117 crore against claims reported

worth Rs 13,692 crore till December 2017. However, during drought/flood years, claims paid

would surpass gross premium collected depending on the intensity of weather calamity. Thus,

the effectiveness of PMFBY cannot be judged on the basis of data of one year. .

The case of Tamil Nadu is worth highlighting as the state experienced one of the worst

droughts in 2016-17. The total claim paid to farmers in Rabi 2016-17 is Rs 2,414 crore

against gross premium of Rs 1,232 crore and the premium to claim ratio of 1.96 (196

percent). The yield data on CCE for Rabi 2016-17 was furnished to insurance companies in

time (by 1/05/2017) and the state government also paid its share of premium subsidy to the

insurance companies. As a result, most of the farmers in Tamil Nadu received claims for their

crop damage caused by drought in that season. This stands as an outstanding example that

could be emulated by other states to provide yield data and premium subsidy on time to

insurance companies. The case of Karnataka is also worth mentioning as they have made a

portal dedicated to crop insurance and all the information relating to this scheme is made

17

available on this website (Box 1). Thus insurance companies could disburse claims within

one week of receipt of yield data.

BOX 1: CASE STUDY OF KARNATAKA

Karnataka Government has made Samarakshane portal which has been operational for

about 20 months. It handles all facets of PMFBY right from issue of notification till the

payment of the compensation, including updation of such compensation details. Number of

crop cutting experiment required for CCE is 4 for major crop and notified at Gram

Panchayat level and 10 for minor crop notified at Hobli (sub taluka) level. The number of

experiments under NAIS during Kharif 2015 was 74,242 and this has increased to 85,166

in Kharif 2016 and further to 88,434 in Kharif 2017. For crop cutting experiments, mobile

phones have been made mandatory. Mobile phones were introduced under Kharif 2016 and

as induction of mobile phones was delayed, 32,447 experiments out of 85,166 experiments

were conducted by mobile phones. In Rabi & Summer 2016-17 all 52,208 experiments

were conducted using mobile phones. They are used to capture images of CCE increasing

transparency and accuracy of the data.

It is not just the Crop Cutting Experiment data that is given to the insurance company. It

includes other information such as claim statements, farmer-wise including farmer’s

Aadhaar number and account number. The insurance company can make the payment soon

after the sheet is given.. However, compensation is delayed by some insurance companies

as they raise objection on the CCE data provided by the government. To address this

issue, since Kharif 2017, insurance companies are made to participate in CCE and can raise

objections on the mobile phone platform itself. Thereafter, they would not be allowed to

raise any objections at a later point of time. This will enhance transparency in the data

received for CCE so that claims could be disbursed to farmers on time.

Thus, other states should design similar portal like Karnataka and provide complete

information of CCE, use of technology, updation of pictures from CCE and provide timely

information to insurance companies and also involve them in CCE. State portals should be

linked to crop insurance portal of GoI so that there is no mismatch in data. State portals

should be linked to crop insurance portal of GoI so that there is no mismatch in data.

The litmus test of any crop insurance scheme depends on quick assessment of crop damage

and payment of claim into farmers’ bank account. The infrastructure to make this scheme

fully operational is still inadequate. Timely submission of yield data by State government to

the insurance companies is necessary so that they can finalise the claims expeditiously and

pay the claims to farmers. .

A comparative statement of these three schemes, NAIS, MNAIS, and WBCIS, on various

parameters is given below in Table-7.

18

Table 7: Comparison between NAIS, MNAIS and PMFBYs

Details

NAIS

MNAIS

PMFBY (2016-17)

Highlights of PMFBY

1. Penetration of these schemes

in terms of farmers covered

(average between 2013-14 and

2015-16 for NAIS and MNAIS)

Covered 20.3 million

farmers (7 million farmers

in Rabi season and 13.3

million farmers in Kharif

season)

Covered 7.7 million farmers

(3.3 million farmers in Rabi

season and 4.4 million

farmers in Kharif season)

Covered 55.1 million farmers

(16.2 million farmers in Rabi 2016-

17 and 38.9 million farmers in

Kharif 2016)

Increase in farmers

covered by 96 percent

2. Coverage in terms of area

insured (average between 2013-

14 and 2015-16 for NAIS and

MNAIS)

Covered 25 million

hectares (9.2 million

hectares in Rabi season and

15.8 million hectares in

Kharif season)

Covered 8.3 million hectares

(3.4 million hectares in Rabi

season and 4.9 million

hectares in Kharif season)

Covered 55.4 million

hectares(18.9 million hectares in

Rabi 2016-17 and 36.6 million

hectares in the Kharif 2016)

Increase in area

coverage by 66 percent

3. Use of Crop Cutting

Experiments (CCE)

Based on block level:

Panchayat provision was

present

Based on Panchayat level.

Based on Panchayat level.

Increase in the number

of CCE

4. Level of Indemnity

Three levels of indemnity—

90 per cent, 80 per cent and

60 per cent, corresponding

to low-risk, medium-risk

and high-risk areas

Two levels of indemnity-90

percent and 80 percent

Three levels