1 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

AVID STRATEGIES

GCCISD SOCIAL STUDIES

STRATEGIES, INSTRUCTIONS,

AND TEMPLATES

2 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTERACTING WITH TEXT AND VISUALS – PAGES 3 - 17

Strategy

Page(s)

Strategy

Page(s)

Cornell Notes

4-6

Reflective Journal

12

Understanding Levels of Questioning

7

Speculation-Prediction Journal

13

Dialectical Journal

8

Textbook Reading Strategies

14

Metacognition Journal

9

Storyboarding

15

Problem-Solution Journal

10-11

OPTIC for Visual Analysis

16-17

READING FOR UNDERSTANDING – PAGES 18 – 30

Strategies for Expository Text

19

Reciprocal Teaching

25

Introducing the Textbook

20

Question the Author

26

Chapter Tour

21

ReQuest

27

Anticipation Guide

22-23

Read, Write, Speak, Listen

28

Think Aloud

24

Concept Map

29-30

GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS – PAGES 31 – 38

Graphic Organizers/Thinking Maps

32-36

Other Graphic Organizers

37-38

WRITING TO LEARN/LEARNING TO WRITE – PAGES 39 – 53

Pre-Write and Free-Write

40

Write a Letter to the Editor

46

Quickwrite

41

Write from Different Perspectives

47

Historical Narrative

42

Primary Source Re-write

48

Sensory Moment in Time

43

“I” Source

49

Interviewing a Historical Figure

44

Writing Poetry

54-63

Writing an Editorial

45

ANALYZING PRIMARY SOURCES – PAGES 54 – 63

ACAPS

55—56

Create an Editorial Cartoon

60

Analyzing a Photograph

57

Analyzing Less Traditional Sources

61

Collaborative Inquiry

58

Analyzing Data

62

Editorial Cartoon Analysis

59

Evaluating a Website

63

STRUCTURED DISCUSSION/ACCOUNTABLE TALK – PAGES 64 – 78

GROUPS Acronym

65

Inner-Outer Circle

71

Preparing Students for Discussion

66

Socratic Seminar

72-74

Think, Pair, Share (and variations)

67

Philosophical Chairs

75

Character Corners

68

Debate

76-77

Four Corners

69

Character Groups

78

Fishbowl

70

ORAL PRESENTATIONS – PAGES 79 – 86

TPR (Total Physical Response)

Vocabulary

80

Reader’s Theater

84

Oral Essay

81-82

Tableau

85

Meeting of the Minds

83

The Hot Seat

86

3 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SECTION ONE

INTERACTING WITH TEXT OR VISUALS

4 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Cornell Notes

Instructions

One Third of the Paper

Two Thirds of the Paper

Connections to Notes

Notes

This can include:

• Main ideas

• Vocabulary terms

• Questions

• Reflections

• Reactions

• Drawings

• Inferences

• Opinions

• Interests

• Connections to other

events

• Significance

Students take notes here from lecture, reading, video,

etc.

Summary of Most Important Ideas:

5 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Cornell Notes

Template

Connections to Notes

Notes

Summary of Most Important Ideas:

6 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Cornell Notes

Template with Lines

Connections to Notes

Notes

Summary of Most Important Ideas:

7 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

UNDERSTANDING LEVELS OF QUESTIONING

Bloom’s

Costa’s

Social Studies involves making judgements about people and events; judge the

worth of the content/material

Level 3

Evaluate

Argue

Criticize

Assess

Persuade

Evaluate

Judge

Recommend

Convince

Opinion

Social Studies involves making sense out of a jumble of facts; reshape the

content/material into a new form

Synthesize

Imagine

Infer

Create

Predict

Hypothesize

Design

Compose

Propose

Speculate

Social Studies involves figuring out complicated situations; break content/material

down to understand it better

Level 2

Analyze

Compare

Classify

Categorize

Contrast

Examine

Question

Characterize

Investigate

Tell Why

Social Studies involves applying lessons of the past to the present; use what

you’ve learned to apply the lessons of the past to another time or era

Apply

Demonstrate

Construct

Apply

Organize

Map

Utilize

Illustrate

Model

Imitate

Social Studies involves explaining people and events; show that you understand

the facts you’ve learned

Interpret

Chart

Show

Restate

Speculate

Explain

Translate

Summarize

Describe

Report

Social Studies involves people, events, and dates from the past; recall what you

have learned

Level 1

Recall

Name

Locate

Record

Define

Memorize

Cluster

Identify

Label

List

8 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Dialectical Journal

Instructions

Students divide a piece of paper in half and then copy an important passage, chart,

map, photograph (description is fine for a visual) on the left side. On the right side, they

respond to the text by:

• Asking a question

• Analyzing (breaking down the various parts)

• Interpreting (explaining their view of the meaning)

• Evaluating (explaining the value)

• Reflecting (expressing personal thoughts or opinions)

• Making personal connections

• Creating a drawing or illustration

• Relating it to a different text or visual

• Summarizing the text

• Predicting the effect

Passage or Quotation from

the Text or Visual

Student Response

1

The text could be a fact, quote, picture

or map

Student may make a reaction to the

quote

2

Quote

Student may make an analysis,

question, or connection

3

Text/fact

Student may ask a question, evaluate,

or make a prediction

4

Picture/graph

Student may interpret, question, or

summarize

5

Chart

Student may question, evaluate, or

write a reaction

9 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Metacognition Journal

Students divide a piece of paper in half. On the left, they record “What I Learned” and

on the right, they record “How I learned It.” The teacher should indicate how many

examples should be included for each reading/visual.

The metacognition section can include:

• Explaining what enabled the student to gain the most from the experience

• Strategies the student used to gain knowledge

• What the student would do differently if they were able to go back to the project

or task

What I Learned

How I Learned It

1

2

3

4

5

10 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

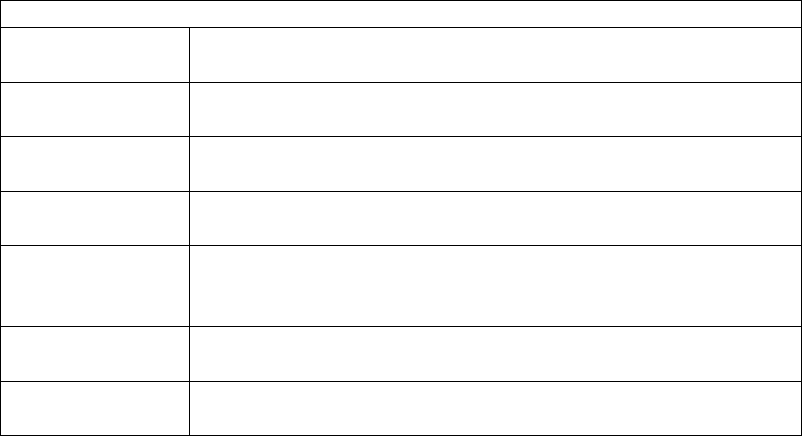

Problem-Solution Journal

Instructions

Problem-solution journal writing encourages students to interact with a reading, artifact,

or visual. It encourages the students to record their thinking about actual solutions to

problems presented, as well as connecting past problems and solutions with present

ones.

Problem-Solution Journal

Version One

Title of Source:__________________________________________________

As you read, identify problems found in the left column. In the right column, identify and

explain solutions. These can be solutions discussed in the reading or solutions that have

been used in the past for similar situations or solutions you think up on your own.

PROBLEM(S)

SOLUTION(S)

1

2

3

4

11 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Problem-Solution Journal

Version Two

Title of Source:___________________________________________________

As you read, identify problems found. For each problem, identify at least two possible

solutions and explain the probable consequences – positive and negative – of each

solution. Finally, identify and explain the best solution for each problem.

Problem:

Possible Solution #1

Possible Solution #2

Possible Solution #3

Consequences of

this Solution

Consequences of

this Solution

Consequences of

this Solution

Best Solution and Why:

12 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Reflective Journal

What I Did

What I Learned

Questions I Still Have

Things that Surprised Me

Overall Response

13 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SPECULATION-PREDICTION JOURNAL

Instructions

Speculation-prediction writing allows students to interact with a text, document, visual,

internet site, etc. Students consider the events and material and predict the possible

effects. This strategy helps to develop students’ understanding of the complexity of

cause-and-effect relationships as well as to recognize recurring themes over time.

Have students divide their paper in half. On the left side, they will record “What

Happened” and on the right they will record “What Might/Should Happen as a Result.”

Students should be encouraged to think about the “what ifs” and speculate about

consequences.

What Happened (Facts)

What Might/Should Happen as

A Result (Speculation/Prediction)

1

2

3

4

5

14 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Ideas for Textbook Reading

There are a number of excellent strategies for helping students interact more deeply

with their textbook – just a few of these are listed below. We encourage teachers to be

creative and have students do more than just “read the section and answer the

questions at the end.”

Interacting with the Textbook – have students:

• Turn the titles, headings, and subheadings into question prompts beginning with

“explain” or “describe” and then answer those questions

• Create new titles, headings, and subheadings for each section

• Develop questions from the text, pictures, or data

• Prepare a graph, chart, or table using information in the text

• Write a poem about a key idea, term, or character

• Make inferences (given a fact, what else is probably true?) from the text

• Provide new examples or make connections to other times in history (either from

before or later)

• Write a script or dialogue and role-play the situation or dilemma

• Evaluate a section in the text by questioning the author’s purpose and credibility

• Develop “what if” statements from the text, pictures, or data

• Relate the text to personal experience

• Compose metaphors or similes for events or issues in the text

• Create an analogy

• Make a visual interpretation of the reading using words, symbols, and pictures

15 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Storyboarding

Instructions

Storyboarding is a strategy requiring students to sequence a series of events or

concepts by writing summaries, creating illustrations, and posing questions (remember

to have them use the various levels of questions from Bloom’s or Costa’s). This activity

helps students develop skills in chronological reasoning, summarizing, and causation.

Have students divide a piece of paper (poster size is best, but any will work) into the

number of sections corresponding to the number of sections in a selected chapter or

reading. After reading each section, students should:

• Create a title for that section

• Write a short summary of the section

• Create an illustration of the information (this should be the largest portion of the

section)

• Pose at least one question that is not directly answered in the text (an “I wonder”

question)

16 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

OPTIC FOR VISUALS

Instructions

OPTIC is a well known strategy for helping students interact with visuals. It works

particularly well with paintings, photographs, and posters. Please make sure students

understand that they can complete an OPTIC organizer in any order they choose –

frequently, it’s easier for students to identify parts before they try to give an overview.

As with ALL AVID strategies, this strategy works best when students create their own

version of the organizer. It is useful to have a template for students to use while initially

learning the strategy, however, a template also makes students believe that their

response is limited to the space given and we obviously want them to give as many

answers as they can come up with rather than staying inside a box, so we ask teachers

to stop using the template as soon as possible after teaching the strategy and encourage

students to answer each part as completely as possible – sometimes it’s better not to

draw the boxes until the answers are complete.

O

OVERVIEW

Students give an overview of what they see in the image, what it seems to

be about in a general sense.

P

PARTS

Students identify all the specific parts of the work, giving details, colors,

figures, arrangements, groupings, shadings, patterns, numbers, etc.

T

TEXT

Students analyze the text (starting with any title or caption, but also

looking for text within the image). Have them think both literally and

metaphorically for meaning. What does the text suggest and why was it

included in the image?

I

INTER-

RELATION

-

SHIPS

Have students discuss the interrelationships in the image – both how the

parts are related to one another and how they are related to the image as a

whole. Consider how all the parts come together to create a mood or to

convey an argument or meaning.

C

CONCLUSION

Students write a conclusion paragraph about the image as a whole,

including analysis of what its creator intended to convey as well as how

effectively it conveys its message and the parts that contribute to that

effectiveness.

17 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

OPTIC

O

Overview

Write a brief overview of the image; in one or more complete sentence(s), what is this image about?

P

Parts

Take note of all the parts in the image – important details, colors, figures, textures, groupings,

arrangements, patterns, shadings, numbers, etc. Whichever are relevant to this image.

T

Text

What is the title? Is there a caption? What do these tell you about the meaning of the work? Is there

any other text in the image – labels, speech bubbles, signs, etc.? How do they relate to the meaning or

message of the work?

I

Interrelationships

Specify the interrelationships in the image – how are the parts of the image related to each other?

How are they related to the image as a whole? How do the parts of the image come together to create

a message, mood, meaning, or convey an idea or argument?

C

Conclusion

Write a brief conclusion paragraph about this image as a whole, including some discussion of the

creator’s intent and how effectively the image conveys its intended meaning or message.

18 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SECTION TWO

READING FOR UNDERSTANDING

19 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Strategies for Reading Expository Text

Prior to the Reading – Establishing a Purpose/Understanding Text Structure

• Pre-read the text by reading title, subtitles, and bold printed words/terms

• Examine visuals, charts, graphs, and maps

• Preview learning outcomes, review questions, and chapter summaries

• Connect to prior knowledge using KWL chart, media clip, children’s book, tell a

story

• Create a purpose for the reading

• Learn and retain academic vocabulary

During the Reading – Monitor Comprehension

• Teach the organization of the text structure (charting the text)

• Vary the reading instruction: read aloud, shared reading, choral reading, partner

reading, small group reading, and independent reading

• Pause to connect ideas within a text

• Use graphic organizers to understand the reading

• Mark the text: circle key terms, cited authors, and other essential words or

numbers; underline the author’s claims and other information relevant to the

reading purpose

• Use instructional strategies that improve comprehension: thinking aloud,

questioning the source, reciprocal reading, or ReQuest

• Enrich the content with primary sources

• Provide varied learning activities: dialectical responses, storyboarding, Cornell

notes, reciprocal reading, questioning the author, pre-writes and quickwrites, and

poetry writing

After the Reading – Extend Comprehension

• Summarize the text

• Discuss what you learned or complete a reflective journal response

• Design extension activities, projects, simulations, or performances

• Put “social” back in social studies – structured discussions like Socratic Seminar,

fishbowl, inner-outer circle, debate, character corners, and four corners

discussions

20 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Introduce the Textbook

Instructions

At the beginning of the instructional year, students benefit from the teacher conducting

an introduction to the textbook, explaining how the book is laid out, what its special

features are, and how to navigate the book.

Consider the following concepts/ideas:

• Prefaces, forewords, and introductions give the author(s) a chance to explain why

the book was written and how it is organized – have students read the introduction

and explain what it told them about the textbook

o This can be done through Read-Think-Pair-Share or some other collaborative

activity

• The Table of Contents provides a “road map” of the textbook

o Have students find specific pages, give examples of how to use the Table of

Contents, or even use the Table of Contents to find specific pieces of

information

• The glossary gives definitions of terms used in the textbook

o Ask students to find the glossary and find examples of the types of terms

included and what they mean

• The Index provides the fastest means of finding information in the textbook

o Give the students three topics covered in the book and have them use the

Index to locate where information about those topics can be found

o Have students discuss and determine the different kinds of fonts used in an

index and what they mean

• Assign a chapter and have students list all the different ideas that help them

understand while reading the chapter – be very specific

o Pre-questions, objectives, pictures, footnotes, etc.

21 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Chapter Tour

Instructions

This is a frontloading technique used to improve reading comprehension of a chapter or

textbook. The process involves guiding or talking students through a chapter, pointing

out features of the text – vocabulary, pictures, charts, graphs, timelines, major ideas or

concepts. This prepares students for successful reading and comprehension.

Step One

Orally guide students through the chapter in order to build background knowledge by

asking probing questions about each of the following:

• The Chapter Title – identifies the main idea of the reading

• Subtitles – present the important concepts, themes, ideas, and events that

support the main idea

• Photographs and Illustrations – give visual cues to better understand the context

of the reading

• Charts and Graphs – give more specific information about ideas in the reading

• Vocabulary Words – must be understood in the context of the reading

• Timelines – present the order in which events take place

Step Two

Have students create a list or paragraph describing what they know about the main idea

or chapter title.

Have them share their list or paragraph with a partner to see if either is missing any

important information.

Students are now ready to read the chapter.

Students may also be assigned to work in pairs to create their own chapter tour after

becoming familiar with the strategy.

22 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Anticipation Guide

Instructions

An anticipation guide is a frontloading strategy that forecasts major ideas on a topic or

reading and activates thinking about a topic by presenting statements about the main

ideas or vocabulary prior to reading a text. This strategy provides a focus for reading

and encourages students to be actively involved with the text by anticipating issues the

students might encounter. The strategy can also be used with visuals.

The teacher will write five questions in a questionnaire that students respond to by

agreeing or disagreeing with each statement before they read. After completing the

reading, students return to the statements in the Anticipation Guide and either reconfirm

or change their response and then justify their response by locating evidence in the text

to support it.

Before Class:

1. Read through the selected text you plan to assign to students and develop four

to six statements based on important points or terms.

2. Create statements that students can agree or disagree with using the template.

During Class

1. Hand out the Anticipation Guide and have students agree or disagree with each

statement in the column that says “Pre-reading.”

2. In groups or as a whole class, poll students to see who agrees and disagrees with

each statement – mark the results somewhere visible in the room.

3. Give the students the selected text and ask them to read it carefully, marking

important ideas in their notebook, or highlighting or annotating the text.

4. After carefully reading and marking the text, ask students to look at the

Anticipation Guide again and mark the Post-reading column.

5. Students should search for evidence in the text that supports their claim and

then restate that evidence in their own words (as well as citing the page number

for the evidence).

6. Have a class discussion on the evidence found as well as any continued

disagreement over the statements.

*Note – it is difficult in this format for us to provide a template that is easily editable for

teachers; however, a simple Google search for Anticipation Guide templates will bring up

a variety of forms and templates you can easily modify for your own classroom.

23 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Anticipation Guide

Template

Title of Text:

Pre-reading

Statement

Post-reading

Pg. #

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

☐

☐

☐

☐

Restate Evidence in Own Words:

Pre-reading

Statement

Post-reading

Pg. #

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

☐

☐

☐

☐

Restate Evidence in Own Words:

Pre-reading

Statement

Post-reading

Pg. #

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

☐

☐

☐

☐

Restate Evidence in Own Words:

Pre-reading

Statement

Post-reading

Pg. #

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

☐

☐

☐

☐

Restate Evidence in Own Words:

Pre-reading

Statement

Post-reading

Pg. #

Agree

Disagree

Agree

Disagree

☐

☐

☐

☐

Restate Evidence in Own Words:

24 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Think Aloud

Instructions and Ideas

A think aloud models for students the thought process of pausing and connecting, which

is what good readers do while reading difficult and complex text. The teacher verbalizes

their thoughts while orally reading a source, pausing and connecting by “thinking

aloud,” (e.g., questioning the author, recognizing bias, defining vocabulary, clarifying a

difficult passage, making predictions, drawing inferences, etc.).

Instructions

1. Prior to distributing the reading, mark the first third of the selected text with

places you plan to stop and think aloud (see the list of prompts below for ideas

to help choose those places).

2. Distribute the text and have students read it.

3. Model “thinking aloud” by reading the text and pausing at marked places to

verbalize your thinking. Students can take notes on your “think aloud.”

4. Direct students to continue the “think aloud” by continuing to read through the

text on their own and mark in the text where they might pause to think and

connect.

5. Have students share their work and discuss similarities and differences.

List of Prompts for Thinking Aloud

• I know this word means…because…

• The author seems to be suggesting here that…

• This reminds me of…

• I am picturing what this might look like…

• I wonder why…

• I would like to ask the author…

• I wish I knew why…

• This viewpoint seems biased because…

• This part suggests that something else might also be true…

• I can relate to this because…

• I wonder how this connects to…

• This seems very similar to…

• I remember when…

• I really question this because…

25 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Reciprocal Teaching/Reading

Instructions

Reciprocal reading, like a Think Aloud, provides students an opportunity to interact with

text under the guidance of a teacher modeling or providing instruction related to the

things good readers do while grappling with difficult text.

This strategy uses five specific skills while reading develop understanding of the text,

and part of the strategy involves helping students understand which of the five skills to

use at any given point in a text – sometimes all five will be used, sometimes only two,

sometimes one is used several times, etc.

This is a collaborative activity and can be done whole class with the teaching leading, in

small groups with one reading and the others reacting, or with partners who share the

roles.

Instructions

1. Reader reads aloud, pausing regularly to allow the group or partner to respond

using one of the five skills below.

2. Students should share roles, rotating reading and responding responsibilities.

Teachers should scaffold this activity by modeling initially, then marking text ahead of time so

groups know when to pause, and gradually releasing responsibility to students.

The Five Skills/Strategies

A. Predict – using information from the text, make a prediction about what comes

next (either within the text or later); the prediction should be logic-based

1. “I predict that…”

2. “I wonder why…”

B. Question – developing a question that is directly answered from the text, requires

an inference or evaluation beyond the text, or connects to other text

1. “I wonder if…”

2. “I’m curious whether…”

3. “Why does…”

C. Clarify – this is a process used to clear up confusing parts of the text and may

focus on an idea, word meaning, or term

1. “When I began reading this, I thought…now I know…”

2. “It would be easier to understand this if it said…”

D. Visual – creating a mental or word-visual to describe the information

1. “I can see…”

2. “I can picture what this looks like…”

3. “I imagine this looking like…”

E. Summarize – summarizing the main ideas presented in the reading; retell the

key points in your own words

1. “Another way to say this is…”

26 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Questioning the Author

Instructions

This strategy unfolds a series of queries with the author, helping students understand an

author’s purpose. Throughout the reading, students engage in a series of questions

about the credibility of the author’s sources and ideas and decide if the reading is

convincing. Students use the text, their questions, and discussions of possible answers

to draw conclusions.

Make sure you model this strategy with students before asking them to use it on their

own. Just as with a Think Aloud, students should mark the text to show where they

would pause and ask a question.

Questions for the Author

• Why does the author use this title?

• What is the author trying to say here?

• This is what the author says, but what does it really mean?

• The author uses an interesting example here to make the point…

• Why does the author continue to use this term?

• How does this connect to…?

• I may be seeing some bias in the author’s viewpoint…

• This language seems to be biased; I wonder why the author used it?

• The author cites specific sources as experts, but does the author know who they

are?

• Does this argument even make sense?

• I would like to ask the author…

• What information has the author added to this?

• Are the author’s sources credible? Why/why not?

• I really question that…

• How does the author stand on this issue? How can I tell?

• Is the article convincing? Why/why not?

27 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

ReQuest

Instructions

ReQuest is an interactive reading, inquiry, and discussion activity in which students

generate and request answers to questions they write while engaged in reading. This

strategy can be done in pairs, groups, or whole class. The reading can be done

independently, or as a read-aloud activity in pairs, groups, or teacher-led.

Instructions

1. Preview the reading with the class by noting title, subtitles, important vocabulary,

charts, graphs, maps, and pictures that help build knowledge prior to reading.

2. Explain to students that they will be writing higher-order questions (Costa’s

Levels 2 and 3) while reading (or listening).

3. Model the process of questioning by reading aloud a portion of the text, pausing,

and then asking a Level 2 or 3 question.

4. Students continue the process by either reading independently and generating

questions, or listening while a partner or the teacher reads aloud and then

discussing and generating questions. Have students refer to the Understanding

Levels of Questioning on Page 7 of this guide and focus on writing Level 2 and

3 questions only.

5. After reading is complete, students should discuss the questions they have

generated with a partner or small group. Share with the group why they asked

this question and make a decision about the most interesting or “best” question

to share with the class.

6. Have a class discussion over student questions.

7. As an exit ticket, have students share what they learned most about the content

in the reading by asking and sharing questions with other students.

28 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Read, Write, Speak, Listen

Instructions

This cooperative activity provides opportunities for students to read, write, speak, and

listen about specific topics before studying an historical event. This helps build

background knowledge and interest about topics to be studied.

Instructions

1. Select four short high-interest texts about one topic. The text should be no more

then two pages in length.

For example, if teaching the Civil War, you might include a reading about

the Lincoln Presidency, military strategy, Andersonville Prison Camp, and

the life of a Confederate Soldier

2. Arrange students in groups of three or four. Assign each student a different topic

to read. Students then read their assigned text.

3. After reading, students return to the text and create a list of important and/or

interesting facts to be discussed at the table.

4. Each student should be given 3 – 5 minutes to explain their notes about their

reading, while the others in the group take careful notes.

5. Each group is given one piece of paper to construct their writing. Begin the

writing process with the first reader’s topic.

Reader #1 writes a topic sentence about their reading

Student #2 adds one sentence about the SAME reading to the paragraph

Student #3 adds another sentence

Student #4 adds another sentence

Continue rotating until time is called or ideas are exhausted.

6. The writing process continues with student #2 constructing a topic sentence

for the second reading. Continue until all four readings have a paragraph.

29 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Concept Map

Instructions

A concept map is very similar to the Frayer Model used by many teachers for vocabulary

instruction – it includes the same components. However, a concept map asks students

to complete those components for a larger concept rather than for a specific vocabulary

word or term.

Example Concepts

• Segregation

• Migration

• Industrialization

• Cultural Divergence

• Revolution

• Urbanization

• Inflation

• Scarcity

• Patriarchy

30 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Concept Map

CONCEPT:

Definition (in your own words)

Characteristics

Create a Visual Representation of the Concept

Non-Examples

Examples

31 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SECTION THREE

GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS

32 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Graphic Organizers

Although they use different terms for the specific organizers, AVID recommends the use

of Thinking Maps, along with a few other organizers.

Graphic organizers are a powerful tool for organizing information, using words and

symbols to identify and clarify patterns and relationships. The decision about which type

of organizer to use depends on the purpose of the learning task.

In almost all cases, graphic organizers are most powerful when they are generated by

students, so we are not including templates – just descriptions and instructions. Also,

make sure students understand that exemplars are intended to give them an idea of the

pattern of the organizer – there are no hard and fast rules about the number of lines,

boxes, circles, etc. on any map. They should include as many ideas as possible, not be

limited by the organizer or map.

Thinking Maps can and should be used to reinforce specific thought-processes,

regardless of content or task.

Task-oriented graphic organizers should be used when the task itself is part of

understanding the content.

33 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS

Descriptions

Descriptive Organizer (Bubble Map)

Used for defining, explaining, describing

Compare and Contrast Organizer (Double Bubble Map)

Used for comparing and contrasting

34 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Classification Organizer (Tree Map)

Used to categorize, organize, understand hierarchy

Cause and Effect Organizer (Multi-Flow Map)

Used to understand cause and effect

35 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Sequence Organizer (Flow Map)

Used to understand the order and stages of an event or events.

Parts and the Whole Organizer (Brace Map)

Used to understand the various parts that make up a whole (main and supporting ideas)

36 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Analogy Organizer (Bridge Map)

Used to understand relationships, make inferences and comparisons

37 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Other Graphic Organizers

Annotated Timeline

Used for understanding the timeline of a sequence of events, using visuals and

annotations to clarify concepts and events.

Understanding Events Organizer

Used for understanding the relationships between key information and events.

38 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Web Diagram

Used for brainstorming, creative thinking

39 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SECTION FOUR

WRITING TO LEARN AND

LEARNING TO WRITE

40 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Pre-Write and Free-Write

Instructions

Pre-write and Free-write provide time for students to express thoughts and ideas

without worrying about traditional writing conventions. The strategy can be used over a

specific topic, event, person, primary source, or visual.

Instructions

1. Pre-write

Identify the topic for the writing and give them approximately 5 minutes to

brainstorm a list of ideas/facts/examples about the topic.

2. Pair-Share

Have students share their lists with a partner, identifying major similarities and

differences between their lists. Choose the most important or interesting ideas

on their lists to share with the class.

Class discussion regarding the shared ideas.

3. Free-write

Give students about 10 minutes to summarize, explain, or describe the ideas

from their list (keeping the main point of the topic given in mind). During this

free-write, students should not be concerned with writing conventions; they

are instead focused on generating ideas, adding details and examples for as

long as time allows.

41 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Quickwrites

Instructions

A quickwrite is a short writing assignment, in which students respond to a prompt

quickly and concisely. These are often used as formative assessments, such as Exit

Tickets, bellringer activities, or transition activities.

Sample Prompts for Quickwrites

• In three sentences, summarize what you learned about (reading, event, person,

place, etc.).

• From the reading we did for homework, generate three level 2 or 3 questions for a

class discussion.

• Create an illustration, symbol or drawing about the reading and explain its

meaning.

• Examine the graph (picture, map, timeline) on page ___ and write a summary of

its meaning.

• Develop “what if?” statements from the reading (picture, data).

• What questions would you ask (historical figure)?

• This is a controversial issue – how would you support your position on it?

• Write a dialogue of a conversation between yourself and (historical figure).

• Create a political or editorial cartoon about the reading.

• 3-2-1 – Write three things you learned, two interesting facts, and one question

you still have.

• Create a thesis statement over the reading (or video).

• If this event were to happen today, what would be different?

• Would you like to have witnessed this event? Why/why not?

• Which person from this unit would you most like to have dinner with? Why?

• Which technological innovation from this period is most important and why?

• Looking at the picture on page ___, identify one person and explain their

perspective on the events.

• Describe (an event) from a particular point of view.

• Take a position on (an issue) and defend it.

42 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Create a Historical Narrative

Instructions

Writing a fictional narrative about the past invites students to use their knowledge of

history and their imaginations to create a story about facts and events. The narrative

requires research in order to convey the events accurately, and imagination to describe

the sensory detail around an event. Stories also allow students to explore an event from

multiple perspectives as they develop multiple characters.

Instructions

1. Research a topic (a helpful organizer to use for this is the Understanding Events

Organizer on page 37).

2. Create a storyboard chronicling the actions of an event. Under each scene, make

a list of description/action words that paint a picture for a reader.

If you have limited time, this can be the final step of an assignment

3. Create a chart of sensory descriptions using sight, sound, smell, taste, touch.

4. Choose the narrator’s perspective and role.

5. Write the story using vivid descriptions, dramatic action, sensory details to

bring the story to life, and the perspective of the narrator where appropriate.

6. Have students share throughout the writing process with different partners

or groups to help them refine and revise their writing.

43 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

A Sensory Moment in Time

Instructions

Descriptive sensory writing helps students develop empathy for historical figures, both

extraordinary and ordinary. Understanding how characters felt in the context in which

they lived is challenging, but also necessary.

After researching or learning about an historical event, students choose a perspective to

describe (it can be even more powerful if students choose two very different

perspectives).

Instructions

1. Students create a visual portrait of the person they are describing that should

take up about one-half to two-thirds of the page.

2. On the remaining space of the paper, students should:

A. Give a brief summary of the event/context

B. Give a brief description of the person they are describing

C. Explain the person’s experience from a sensory perspective:

1. Sight – “I would have seen…”

2. Sound – “I would have heard…”

3. Taste – “I would have tasted…”

4. Touch – “I would have felt…”

5. Smell – “I would have smelled…”

44 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Interview an Historical Figure

Instructions

Developing questions to ask a historical figure and then brainstorming that figure’s

responses gives students the opportunity to review material and interact critically with

it, as well as develop understanding of different perspectives.

After learning about an event or period, have students choose a major historical figure

from the period and write a series of 10 to 15 interview questions for that person as if

they were a journalist questioning the person. Students can then either write responses

to those questions or swap papers and answer the questions someone else wrote over a

different figure.

45 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Write an Editorial

Instructions

Writing an editorial is an opportunity for students to express opinions and reactions to a

controversial issue. They can either express their own opinion or take the perspective of

a historical figure to demonstrate their understanding of that person’s viewpoint.

Instructions

1. Students research an event or issue (either historical or current).

2. Using the format below, students write a draft of an editorial regarding the issue

from a specific perspective (either their own or that of a historical figure).

3. Students share their editorial with a partner – each offers suggestions to the

other for improvement.

4. Students revise and rewrite their editorial, producing a final copy.

FORMAT FOR WRITING AN EDITORIAL

The Opening

Describe the situation and issue as it now exists (or existed at

the time of the person’s perspective being taken).

Identify the writer’s position on the issue and the action the

writer wants taken.

The Body

Explain the reasons that support the writer’s position.

Explain arguments against the writer’s opinion and why they are

not valid or why they are unimportant.

The Conclusion

Explain what will happen if the action demanded by the writer is

not taken and the more positive future that will occur if it is

taken.

46 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Write a Letter to the Editor

Instructions

Letters to the editor gives students an opportunity to express their ideas and feelings

about a topic or issue that concerns or interests them. These letters should be short,

concise, and focused on a single issue. Often, these letters comment on current events.

Students should be reminded that regardless of topic, a letter to the editor should have

opinions based on facts and supported by evidence. These letter may include personal

pronouns, unlike most formal writing, but must remain respectful and timely.

Letters to the editor can be based on historical events (in which the student takes the

position of a historical character) or current events (in which a student expresses their

own viewpoint).

Instructions

1. Students decide on a single issue to address in their letter.

2. Students brainstorm a list of reasons and evidence to support their position.

3. Students write their letters, clearly identifying reasons for their perspective

and evidence to support them.

4. Students share letters with a partner to help with revisions and clarifications

before finalizing their letter.

47 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Writing From Differing Perspectives

Instructions

Having students role-play by taking the perspective of a specific person in history is a

powerful activity that builds understanding of content, context, and perspective.

Instructions

1. Identify a topic or era for students and then brainstorm with the class differing

roles/characters in the period

2. Write a specific question about the era to generate ideas (i.e., “How did

Prohibition affect life for people in the 1920s?”, “How did fears about nuclear

war affect people during the 1950s?”, “How did rising taxes and social

inequalities affect different groups of people in pre-Revolutionary France?”)

3. Students should spend some time brainstorming:

A. The character/figure they want to be

B. Details regarding that person’s perspective on the era/period

C. The writing format they will use (diary entry, editorial, editorial cartoon,

speech, sermon, letter, news story)

4. Students spend time developing and revising their writing, then share with a

partner or group to hear different perspectives and viewpoints.

5. Hold a class discussion about which viewpoints were still missing after the

share activity and why.

48 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Primary Source Rewrite

Instructions

For many students, the ideas and language of historical documents threaten to prevent

them from understanding the past. Giving students an opportunity to work with the

document to rewrite it into contemporary language helps them think through its

meaning and context more effectively.

This activity works best as a collaborative strategy in very small groups of two or three.

Instructions

1. Have students mark the difficult text by noting important and/or confusing terms

2. Students work together to define each of those terms and ideas, using

contemporary language

3. After gaining an understanding of the confusing and difficult terms, students go

back through the text to identify the main idea(s) of each paragraph and write

those ideas in contemporary language

4. Together students work through the entire document to rewrite it into language

that is easily understandable

5. Have student groups share their rewrites, noting similarities and differences in

their rewrites

A. This should be their check for meaning – if any part of their rewrite means

something different, they should go back to the original and determine

which is the better “translation” of its meaning

49 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

“I” Search

Instructions

“I” Search is a paper students plan and take notes in order to create over the duration

of a research project. It gives students the opportunity to describe and reflect on the

process of research, which fosters original thought, reduces plagiarism, and builds

research skills. Often, teachers have students complete this as part of a research

journal.

Instructions

In a research journal or notebook, students record what they already know about a

topic, including any preliminary hypothesis or conclusion.

Students then create an outline that identifies their plan for conducting research and

completing the project – identifying locations to visit, resources to locate, and a

timeline.

As research continues, students note what they have learned from various sources, what

changes they have made to their strategy and timeline and the difficulties and obstacles

they have encountered and how they have overcome those difficulties.

Once the research is complete students can write their “I” Search paper. This should

include narrative describing:

• Phase I – The Opening

o What I already knew about the topic

o My preliminary hypothesis/conclusion

• Phase II – The Research Process

o Where I began my research

o How I was led to other sources and sites

o How my strategy changed from the original plan

o Difficulties I encountered and how I dealt with them

• Phase III – Analysis of What I Learned

o The most important things I learned about my topic was…

o Some details/quotes/examples that support this are…

• Phase IV – My Growth

o The skills I developed or improved during this research

o I will do things differently in the future by…

• Phase V – The Product

o Description of final product

50 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Writing Poetry

Writing poetry breathes life into history and social studies, reminding students of the

human element rather than just memorizing dry facts. History and social studies consist

of a fertile field for creative expression through its events, topics, themes, and

characters. Below are some ways teachers can use poetry in the classroom, but there

are many others.

Acrostic Poem

In an acrostic poem a term or name is written vertically and each letter then becomes

the first letter for a word, phrase, or sentence describing that thing. You can also have

students create a poem for an opposing concept or idea using the same strategy.

M D

A I

G V

N I

A N

E

C

A R

R I

T G

A H

T

ABC Poem

Similar to an acrostic, but this time the letters of the alphabet serve as the first letter of

each word, phrase, or sentence describing a topic. This type of poem may end before

the letter Z, as students should focus on telling a story and coming to a logical

conclusion.

51 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Biographic Poem

After learning about a character from the past, the student uses the following framework

to write a poem summarizing major points about the character. Each response should be

a few words, not sentences or phrases.

NAME OF CHARACTER:

Resident of

Three Traits

Related to

Cares Deeply About

Feels

Needs

Gives

Fears

Would like to see

Cinquain Poem

To create a cinquain, students name a topic and then describe that topic using specific

elements:

Name (person, event, invention, etc.)

Two adjectives

Three verbs

Simile (using “like a…” or “as…as…”)

One-word summary

Descriptive Poem

This type of poem invites students to creatively summarize the most important aspects

of an idea, theme, topic, or concept creatively in three lines.

The first line defines the topic, the second line starts with “which” to further describe the

topic, and the third line starts with “when” to clarify the context.

EXAMPLE:

World War I

Trench War was a major way of fighting

Which was horrifying with human carnage

When tens of thousands of men hid, fought, and died

52 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Found Poem

A found poem is a collection of words or phrases that groups have students have found

in various sources that resonated with them as they learned about a topic. Students

individually gather words and phrases and then work together to choose the ones they

want to use to create their “Found” poem over the topic. Students should be encouraged

to look for words and phrases that are emotional, strong, descriptive, and meaningful.

EXAMPLE

Gandhi

Non-violence the law of our species

Violence the law of the brute

Non-violence means conscious suffering

The dignity of man requires obedience to a higher law

Self-sacrifice

Strength through forgiveness

Defy the might of an unjust empire

Through non-violence

Haiku Poems

Haiku poetry invites students to describe a series of events or topics with short and

descriptive poems following a specific structure.

Haiku poetry uses the following structure:

Line One = 5 syllables

Line Two = 7 syllables

Line Three = 5 syllables

EXAMPLE

Islam

Allah is the one

Praise to him they all will cry

Islam is our life

53 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

“I Am” Poem

An “I Am” poem is about a person, group of people, organization, or even an inanimate

object, which uses the ideas of emotions and senses (this can be particularly powerful

when used with an image – “In this photograph of protesters being attacked with fire

hoses by the fire department, write an “I Am” poem from the perspective of the street

lamp.”).

Template:

I am…

I wonder…

I hear…

I see…

I am…

I pretend…

I feel…

I touch…

I worry…

I cry…

I am…

I understand…

I say…

I dream…

I try…

I hope…

I am…

Song or Rap

Rather than writing a poem, consider having students write lyrics for a song or a

(school-appropriate) rap about a topic, event, or person.

54 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SECTION FIVE

ANALYZING PRIMARY SOURCES

55 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

ACAPS

Instructions

ACAPS is one of several types of analysis tools for looking at primary sources (AP-PARTS

is another, often used by AP teachers). All are valuable and teachers should probably

choose one to use with students while analyzing a source.

With ACAPS, as with almost all acronyms used as memory devices in education, the

actual order in which students respond is NOT important and the length of response for

each “letter” may differ widely. Because of this, although we provide a template for you

to use while teaching the strategy, it is recommended that teachers “wean” students off

the template and allow them to create their own organizers as soon as they understand

the meaning of each letter (not just what it stands for, but all the various components of

what it means).

ACAPS stands for:

Author

Context

Audience

Purpose

Significance

56 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

ACAPS – PRIMARY SOURCE ANALYSIS

Template

A

Author

Who created the

source? What do we

know about the

person and his or her

point of view? How

might this affect the

source’s meaning?

C

Context

When and where was

this source created?

What else was going

on there at the time?

How might this affect

its meaning?

A

Audience

For what audience

was this source

created? How can we

tell? Was there more

than one audience?

How might audience

affect its meaning?

P

Purpose

For what reason was

this source created?

Was it effective? How

might its purpose

affect its message or

meaning?

S

Significance

What can be learned

from this source?

What were its main

ideas? Why was the

source important at

its time? Why is it

important today?

57 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

ANALYZING A PHOTOGRAPH

Look at the provided photograph from history and answer the following:

IDENTIFY THE PHOTOGRAPH

Who took this picture and when?

Who was the intended audience (family, friends, the public)?

Why was this photograph taken (keepsake, historical record, news)?

EXAMINE THE PHOTOGRAPH

Describe the action or subject of the photograph.

List the objects shown in the photograph (look at the background, individuals,

and groups shown).

Which details give you the most information about what is happening? Why?

EVALUATE THE PHOTOGRAPH

Based on what you can see in the photograph, what facts are likely to be true?

Explain the impact this photograph may have had on viewers in the past.

In what ways might this photograph be misleading?

58 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Collaborative Inquiry of Sources (Primary or Secondary)

Instructions

Through collaboration and discussion students analyze numerous primary and secondary

sources about a general topic of study. By rotating different sources from group to

group, students are able to conduct an in-depth analysis of the topic.

Instructions:

1. Arrange students in groups of two to four students.

2. Assign each group a different source (some should be text, but others should be

visual or some other type of source).

3. Have each group analyze their source using ACAPS (see page 56 for template).

4. After a specified period of time, each source should rotate to another group and

each group now analyzes a new source.

5. After analyzing each source, each group should hold a discussion about what

they have learned about the topic as well as identify any areas of confusion and

any questions they still have.

6. Hold a class discussion to elicit areas of confusion and questions.

59 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Editorial Cartoon Analysis

Template

Editorial cartoons communicate opinions about current events of their time, using

drawings, words, symbols, exaggeration, and humor to convey an idea or message.

Some cartoonists use them to portray the ills of society, while others attempt to identify

a cure.

Editorial Cartoon Techniques

Symbolism

Using objects, colors, or images to stand for ideas or

concepts

Labeling

Labels are used to clarify identity of people or make

clear what an object is

Caricature

Deliberate distortion or exaggeration of a person’s

features to create an effect

Exaggeration

Distortion of an object or person in size, shape, or

appearance

Analogy

A comparison between two unalike things – usually

one complex and abstract and the other simple or

familiar

Irony

The difference between the way things are and the

way they ought to be

Stereotyping

Generalizing about an entire group by a single

characteristic that may be insulting and/or untrue

Analyze the provided cartoon by answering the following questions:

1. What is the general subject of the cartoon?

2. Who are the characters shown and what do they represent?

3. What symbols are used, and what do they represent?

4. What outside knowledge and facts are needed to understand this cartoon?

5. What is the cartoonist’s opinion about the topic and how can you tell?

6. What techniques did the cartoonist’s use and how effective were they?

60 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Student-Generated Editorial Cartoons

Instructions

Once students are familiar with analyzing editorial cartoons, having them create their

own can help them gain greater insight and understanding of a topic.

Have students first create and then analyze their own cartoon.

Instructions

1. Have students choose a topic and brainstorm all the facts and ideas they can come

up with related to that topic.

2. At this point, students should choose which message or opinion they want to

convey and decide on the details, facts, etc. they will include.

3. Review the techniques of editorial cartoons (from the analysis tool on page 59)

with students and have them decide which techniques they will use.

4. Students should then create their editorial cartoon.

5. After creating their cartoon, have students answer the following in the margins

or on the back:

A. What is the general subject?

B. Who are the characters and what do they represent?

C. What symbols are used and what do they represent?

D. What is your message or viewpoint on the issue?

E. What techniques were used?

61 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Analyzing Less Traditional Resources

When analyzing a poster, painting, sound recording, artifact, or other non-traditional

primary or secondary source, the following questions may be useful:

Questions

• Who created this?

• When was it created and what else was going on there at the time?

• For which audience was this created?

• Why was this made?

• What message, mood, or meaning is conveyed and how?

• What inferences can be made about the object?

• What questions would you like to ask the creator about the object and/or the time

period in which it was created?

62 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Analyzing Data

Instructions

Depending on how data is presented, there are different questions to ask students that

will help them analyze the information and create meaning. Make sure you choose the

questions that are appropriate within each category for the specific graph, chart, or map

being analyzed.

Tables and Charts

• What is the title?

• What does the source information suggest about the reliability of the data?

• Read the headings at the top of each column – what subjects are being compared?

• Read the labels in the far left column – what sub-groups are being compared?

• What can be learned by comparing the different columns?

• Summarize the information shown on this table or chart.

• What inferences can be made from this information?

• What questions NOT addressed in the chart or table would allow for greater

understanding of this topic?

Line and Bar Graphs

• What is the title?

• What does the source information suggest about the reliability of the data?

• What does the vertical axis (left side) of the graph show?

• What does the horizontal axis (bottom) of the graph show?

• If there is a key/legend, what do the symbols indicate?

• Explain what comparisons, trends, or patterns you can infer or predict.

• Summarize what you have learned from this graph.

• What questions NOT addressed in this graph would allow for a better

understanding of the topic?

Circle (Pie) Graphs

• What is the title?

• What does the source information suggest about the reliability of the data?

• If there is a key/legend, what do the symbols indicate?

• What can be learned by comparing the various segments in the graph?

• Summarize what you have learned from this graph?

• What questions NOT addressed in this graph would allow for a better

understanding of the topic?

63 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Evaluating a Website

Template

It is critical that you learn to evaluate all sources of information in order to judge its

accuracy and reliability. This is especially true of information found on the internet. It

can be difficult to determine whether a source is accurate or whether it should be

trusted.

The following questions can guide you as you attempt to decide whether a website is

providing accurate and reliable information.

Authority of the Source

• Is it stated who is responsible for the website’s

content and are their credentials stated?

• Is it a reliable source of information?

• Is contact information given?

Accuracy of the Information

• What is the source of the factual information?

• Can the information be verified?

Objectivity of the Content

• What is the purpose of the website or organization?

• Are the authorities’ biases stated clearly?

Currency of the Information

• How recent is the information?

• How often is the website updated?

64 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

SECTION SIX

STRUCTURED DISCUSSION

ACCOUNTABLE TALK

65 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

GROUPS

G

Give Encouragement

R

Respect Others

O

On Task

U

Use Quiet Voices

P

Participate

S Stay in Groups

66 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Preparing Students for Discussion

Structured discussion is a powerful way to increase rigor and deepen comprehension of

content; however, the quality of a discussion depends in large part on the preparation of

students as well as the complexity of the topic and/or text being discussed. If the

discussion is text-based, it is important for students to read, analyze, and take notes

prior to the discussion. Whenever possible, notes should be taken directly in the margins

of the text itself to help keep the discussion text-based and assist students in using the

text to find evidence to support their ideas.

The following prompts may help students prepare written notes prior to a discussion

(choose questions appropriate to both the text and the planned discussion):

• What surprises or interests you?

• What questions do you have about the text or for its author(s)?

• What connections do you see between the ideas in this text and other ideas, past

or present?

• What predictions can you make?

• Given the facts presented in the reading, what else do you believe may be true?

• What cause/effect relationships do you see?

• What evidence exists to support your ideas?

• What personal connections do you have to the text?

• What are the most important ideas or passages in the text? Why?

Tips for Teachers Facilitating Discussions:

• Start small – use shorter texts and plan shorter discussions and build slowly

• At the start of each discussion, review the guidelines for discussions briefly

• Take notes visibly during the discussion; evaluate students, chronicle ideas

discussed and then use these notes during the debrief to help coach students and

set goals for the next discussion

• Never neglect the debriefing; this feedback is vital if the group is going to grow

with each structured discussion; request non-judgmental comments from students

that will improve future discussions

• Over time, use a variety of texts, visuals, fiction, essays, poetry, quotations,

artwork, editorial cartoons, etc.

67 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Think, Pair, Share

Instructions

One of the most commonly used types of structured discussion, this strategy can be

used “on the fly” by teachers when they determine students would benefit from a

collaborative discussion about content. It can help assess students’ prior knowledge,

help students improve their listening skills, and their ability to analyze material.

Instructions

1. Present students with a specific question, problem, or prompt.

2. Give the class 1 – 3 minutes of quiet time to think and jot down some ideas.

3. Students then share their ideas with a partner, specifically noting the similarities

and differences between their responses.

4. Facilitate a class discussion by having a few students share their responses or

their partner’s responses.

Alternate Versions:

• Think, Write, Pair, Share

o Give students a longer period of time to think and write before sharing with

a partner

• Think, Research, Pair Share

o Allow students to research evidence to support their ideas (either in a

textbook or on an electronic device)

• Think, Pair, Pair, Pair, Share

o Have students rotate partners several times, so each student hears ideas

from a variety of their peers (this works best when the question is very

open-ended, allowing for a wide variety of responses)

68 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Character Corners

Instructions

This strategy requires students to think critically about ordinary or extraordinary people,

adding interest by including multiple perspectives of men, women, and children from

historical or current events. Students have the opportunity to share their insights and

comments with other students.

Instructions

1. Place placards in the corners or walls of the room, each with the name of a

different character being studied. This can be a specific person or a description

of a type of person (i.e., Napoleon Bonaparte, an infantry soldier in the French

army, a peasant working in rural France, Tsar Alexander, etc.).

2. Typically, four names are used (hence, corners), however, you can use as many

as you wish. However, be sure you do not use so many names that students

end up alone in a corner.

3. Present students with a prompt, such as:

• Which character would you like to meet with and why?

• Which character would you have questions for and what are they?

• Which character would have the best perspective on this topic and

why?

4. Give students 3 – 5 minutes to write their responses and then move to the

appropriate placard for the character they addressed.

5. Students should discuss their responses with the other students who addressed

the same character.

6. Students choose (or teacher chooses) one student from each group to record

the group’s discussion and share those with the class.

7. Have each group recorder share out.

8. Facilitate a group discussion by challenging some responses, asking probing

questions, or having students in one group respond to or question another

taking the perspective of the character they chose.

*Note – it is possible that the vast majority of students will choose the same character.

It is important to have students write down their answers before moving to limit the

possibility that they will try to gravitate to the same character as their friends. It is up to

the teacher to decide whether a few students need to move to a different character or

whether to allow larger groups to exist.

69 | Page All strategies adapted from Kurt Dearie and Gary Kroesch, The Write Path, AVID Press, 2011.

Four Corners Discussion

Instruction

Similar to Character Corners, Four Corners allows students to move around the room

and share their ideas with other students. In this strategy, students take a position on a

controversial topic and defend it. This strategy encourages students to listen to the

perspectives of others and be willing to change their position if convinced by another

student’s arguments.

Instructions

1. Write a statement on the board that requires students to take a position

• The American Colonists were justified in their anger over British taxes

• It is more important for the Brazilian government to feed its people

than to protect the remaining rain forest

• It is the government’s responsibility to provide welfare to all citizens in

need

• Feudalism is a better form of government than a strong monarchy or

empire

2. Have students choose one of the following responses and explain their reasoning

in writing:

- I strongly agree because…

- I somewhat agree because…

- I strongly disagree because…

- I somewhat disagree because…

3. Create and post placards in the corners or walls of the room representing each

response. Have students move to their corresponding placard.

4. In their respective corners, students share their reasoning and evidence and