UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA

Los Angeles

A Plea for Justice:

Racial Bias in Pretrial Decision Making

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the

Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

in Social Welfare

by

Matthew Lawrence Mizel

2018

!

© Copyright by

Matthew Lawrence Mizel

2018

!

ii

ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION

A Plea for Justice:

Racial Bias in Pretrial Decision Making

by

Matthew Lawrence Mizel

Doctor of Philosophy in Social Welfare

University of California, Los Angeles, 2018

Professor Laura S. Abrams, Chair

African American defendants are more likely than Whites to be charged punitively by

prosecutors at arraignment, detained pretrial, and sentenced harshly via plea bargain. These

disparities contribute to mass incarceration, because 95% of cases adjudicate by plea bargain

rather than a jury trial. Prior research has found that implicit racial bias (unconscious attitudes

and stereotypes about race) and dehumanization bias (thinking of others as less human) are

associated with racial disparities in areas of the justice system outside of pretrial decision

making. This study poses the following questions: (1) Are implicit racial bias, explicit racial

bias, implicit dehumanization bias, and/or explicit dehumanization bias associated with pretrial

decision making (for each of initial charge, bail, target plea sentence, minimum acceptable plea

sentence, and charge reduction)? (2) What are the relative influences of implicit racial bias,

!

iii

explicit racial bias, implicit dehumanization bias, and explicit dehumanization bias? A total of

148 students from the UCLA School of Law read a fictional criminal case vignette and then

made pretrial decisions in the role of prosecutor. The race of the defendant was randomly

assigned to be either African American or White while all other aspects of the vignette were held

constant. Higher anti-African American/pro-White implicit dehumanization bias was associated

with a less punitive initial robbery charge for the White defendant. Greater anti-African

American/pro-White implicit racial bias was associated with three outcomes for the White

defendant in a direction contrary to implicit bias theory: setting a higher bail amount, targeting a

longer prison sentence for the plea bargain, and being less likely to offer a charge reduction. In

supplemental analyses, participants who believed in the biological basis of race were less likely

to charge the White defendant more punitively. The results suggest that implicit dehumanization

bias and implicit racial bias influence pretrial decision making but that only implicit

dehumanization bias contributes to racial disparity. Future research could test these results with

working prosecutors and defense attorneys to expand the generalizability of the findings.

!

iv

The dissertation of Matthew Lawrence Mizel is approved.

Todd M. Franke

Aurora P. Jackson

Michael C. Lens

Laura S. Abrams, Committee Chair

University of California, Los Angeles

2018

!

v

Dedication

For all the kids in juvenile hall who went through pretrial

while students in my creative writing class.

!

vi

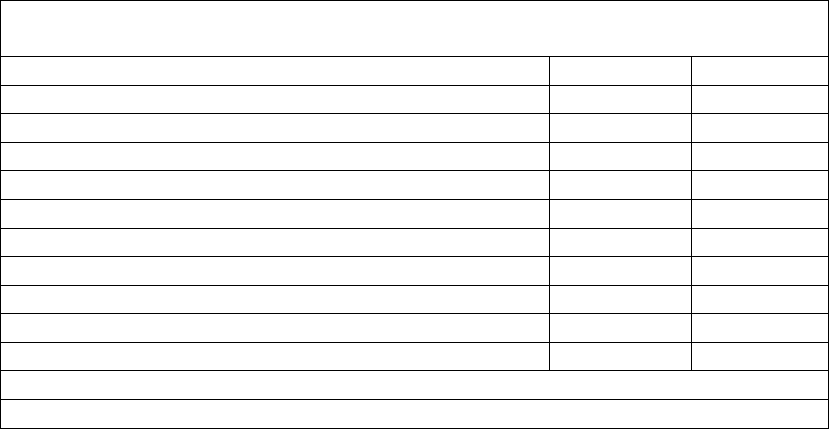

Table of Contents

List of Tables ...........................................................................................................................viii

Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... ix

Vita ............................................................................................................................................ xi

Chapter One: Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1

Consequences of Pretrial Decisions ......................................................................................... 2

Pretrial Decision Making and Social Work .............................................................................. 6

Prior Approaches to Racial Disparity in Pretrial Decision Making ........................................... 9

Innovations of This Dissertation ............................................................................................ 10

Research Questions ............................................................................................................... 12

Hypotheses............................................................................................................................ 12

Overview of Dissertation ....................................................................................................... 13

Chapter Two: Literature Review ............................................................................................... 15

Overview of Chapter ............................................................................................................. 15

Pretrial Procedure .................................................................................................................. 15

Background on Pretrial Detention and Bail............................................................................ 16

Prosecutorial Discretion ........................................................................................................ 18

Appropriate Legal Factors ..................................................................................................... 20

Initial Screening/Charging..................................................................................................... 21

Pretrial Release and Bail ....................................................................................................... 23

Guilty Plea/Plea Bargaining .................................................................................................. 24

Sentencing ............................................................................................................................ 25

Pretrial Decision Making and Cumulative Disadvantage ....................................................... 27

Summary of Studies on Pretrial Decision Making ................................................................. 31

Focal Concerns Perspective ................................................................................................... 32

Research Gaps....................................................................................................................... 35

Chapter Three: Theory .............................................................................................................. 37

Overview of Chapter ............................................................................................................. 37

Implicit Bias ......................................................................................................................... 37

Measuring Implicit Bias ........................................................................................................ 39

Implicit Bias and Pretrial Decision Making ........................................................................... 40

Dehumanization Bias ............................................................................................................ 43

Dehumanization Bias and the Justice System ........................................................................ 44

Dehumanization of African Americans.................................................................................. 44

Infrahumanization ................................................................................................................. 45

Genetic Essentialism ............................................................................................................. 47

Summary............................................................................................................................... 49

Chapter Four: Methods ............................................................................................................. 51

Overview of Chapter ............................................................................................................. 51

Research Questions ............................................................................................................... 51

Hypotheses............................................................................................................................ 51

!

vii

Research question #1: ........................................................................................................ 51

Research question #2: ........................................................................................................ 52

Recruitment .......................................................................................................................... 52

Sample .................................................................................................................................. 53

Protection of Human Subjects ............................................................................................... 56

Data Collection ..................................................................................................................... 56

Criminal case vignette ....................................................................................................... 56

Case perception items ........................................................................................................ 58

Dehumanization IAT ......................................................................................................... 59

Modern Racism Scale (MRS) ............................................................................................ 60

Racial Conception Scale (RCS) ......................................................................................... 61

Procedure .............................................................................................................................. 62

Analysis ................................................................................................................................ 62

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................ 65

Chapter 5: Results ..................................................................................................................... 66

Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 66

Descriptive Statistics ............................................................................................................. 66

Dependent Variables ............................................................................................................. 68

Participant Suspicion ............................................................................................................. 71

Research Question #1 ............................................................................................................ 74

Research Question #2 ............................................................................................................ 85

Chapter 6: Discussion ............................................................................................................... 88

Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 88

Research Question #1 ............................................................................................................ 88

Research Question #2 ............................................................................................................ 93

Additional Constructs ............................................................................................................ 95

Interpretation of Non-Significant Results .............................................................................. 97

Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 99

Implications ........................................................................................................................ 101

Future Research .................................................................................................................. 104

Potential Social Work Contributions ................................................................................... 106

Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 108

Appendix A: Case Vignette ..................................................................................................... 109

Appendix B: Independent Measures ........................................................................................ 121

Case Perception Items ......................................................................................................... 121

Modern Racism Scale (MRS) .............................................................................................. 122

Infrahumanization Measure ................................................................................................. 123

Race Conceptions Scale (RCS)............................................................................................ 124

Appendix C: Participant Suspicion .......................................................................................... 126

References .............................................................................................................................. 132

!

viii

List of Tables

Table 1. Sample Demographics. ............................................................................................... 54

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for the Independent Variables ................................................... 67

Table 3. Independent Variable Correlations .............................................................................. 68

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for Robbery Charge................................................................... 69

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics for Gun Enhancement ............................................................... 69

Table 6. Descriptive Statistics for Battery Charge .................................................................... 69

Table 7. Descriptive Statistics for Total Number of Initial Charges .......................................... 70

Table 8. Descriptive Statistics for Bail ..................................................................................... 70

Table 9. Descriptive Statistics for Target Plea Sentence ........................................................... 71

Table 10. Descriptive Statistics for Minimum Acceptable Plea Sentence .................................. 71

Table 11. Descriptive Statistics for Charge Reduction .............................................................. 71

Table 12. Participant Suspicion by Robbery Charge and Defendant Race ................................. 72

Table 13. Defendant Race by Robbery Charge and Participant Suspicion ................................. 73

Table 14. Multinomial Logistic Regression Results for Robbery Charge for African American

Defendant ................................................................................................................................. 75

Table 15. Multinomial Logistic Regression Results for Robbery Charge for White Defendant. 76

Table 16. Logistic Regression Results for Gun Enhancement for African American Defendant 77

Table 17. Logistic Regression Results for Gun Enhancement for White Defendant. ................. 78

Table 18. Ordinal Regression Results for Battery Charge for African American Defendant ...... 78

Table 19. Ordinal Regression Results for Battery Charge for White Defendant ........................ 79

Table 20. Ordinal Regression Results for Total Number of Charges for African American

Defendant. ................................................................................................................................ 80

Table 21. Ordinal Regression Results for Total Number of Charges for White Defendant. ....... 80

Table 22. Linear Regression for Bail for African American Defendant ..................................... 81

Table 23. Linear Regression Results for Bail for White Defendant. .......................................... 82

Table 24. Linear Regression Results for Target Sentence for African American Defendant. ..... 82

Table 25. Linear Regression Results for Target Sentence for White Defendant. ....................... 83

Table 26. Linear Regression Results for Minimum Sentence for African American Defendant. 83

Table 27. Linear Regression Results for Minimum Sentence for White Defendant. .................. 84

Table 28. Logistic Regression Results for Charge Reduction for African American Defendant. 84

Table 29. Logistic Regression Results for Charge Reduction for White Defendant. .................. 85

Table 30. Summary of Results, Research Question #1 .............................................................. 88

Table 31. Defendant Race by Gun Enhancement and Participant Suspicion. ........................... 126

Table 32. Participant Suspicion by Gun Enhancement and Defendant Race. ........................... 126

Table 33. Defendant Race by Battery Charge and Participant Suspicion. ................................ 127

Table 34. Participant Suspicion by Battery Charge and Defendant Race ................................. 128

Table 35. Defendant Race by Charge Reduction and Participant Suspicion. ........................... 130

Table 36. Participant Suspicion by Charge Reduction and Defendant Race. ........................... 130

!

ix

Acknowledgments

This dissertation was supported by the UCLA Graduate Division Dissertation Year

Fellowship and the Franklin D. Gilliam Social Justice Award.

I have enormous gratitude for my mentors and committee members: Aurora Jackson for

helping me to learn about implicit bias, Todd Franke for training me on the subtleties of

statistics, Mike Lens for scoring the big goal in stoppage time, and Laura Abrams for being a

dissertation chair, advisor, frequent question answerer, mentor, and friend. Thanks also to

Jenessa Shapiro for the methodological guidance and to Josh Aronson for mentoring me through

one undergraduate and two graduate degrees. Tanya Youssephzadeh helped me to successfully

navigate UCLA in ways both big and small, and many faculty within and outside of social

welfare pushed me to think in new ways. I greatly appreciate Lois Davis and Liz D’Amico for

the opportunities at RAND and for furthering my skills in applying research to policy. Finally,

many classmates at UCLA provided practical and emotional support, particularly Charles Lea,

Sara Terrana, and Alejandra Priede-Schubert.

I have much love for InsideOut Writers for providing me with the opportunity to teach

creative writing in the juvenile halls, probation detention camps, DJJ facilities, and California

state prisons. Thanks to the staff, volunteers, and board members for supporting me and my

fellow teachers. I hope I have had as much an impact on my students as they have had on me,

because they changed my life. If not for them, I would not be studying for a Ph.D. or have

selected this dissertation topic.

Thanks to the Anti-Recidivism Coalition for being a second family. I cannot express

enough admiration for the currently incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people who inspire

!

x

me with their determination, strength, and belief in self, especially Felix, Alton, David, Lionel,

Ezequiel, Raul, Chris, Charity, Jimmy, Carlos, Roby, Sam, Jose, Jesse, Jesse, Aaron, Yähnïie,

Ramon, Taylor, Julio, Candice, Vincent, and David. Your insistence on moving forward in life

left me with no other option than to do the same.

So many friends have been instrumental in my life. These are some of them over the last

few years (in a sorta alphabetical order): Jared Blank, Eric Buch, Scott Budnick, Allison Carter,

Anne Chang, Miata Edoga, Rodrigo García, Emma Hickox and Rob Sanderson and Eric Simkin,

Emma Hughes, Katayoon Majd, Misty Oka, Rebecca Russ, Nina Sadowsky, Gregory Sale, Matt

Scelza, David Taylor, Midnight Toker, Renata Turrent, Pete Ubertaccio, Doug Wade and Kerry

Asmussen and Brian Goldsmith, and Erika Woods. I could write a dissertation about what you

have meant to me.

Thanks to “Uncle” Larry for the middle name and the years of belief in me. To my

brother and sister, thanks for the steady stream of positivity and the many meals. They all

mattered. And, to my nieces and nephews, follow your passions. They will take you where

you’re meant to be.

To my Mom and Dad, thanks for teaching me how to write and do math as well as for the

support, encouragement, and love through this process. It was probably a little unsettling to hear

your 40-year-old son say, “I could stay in school forever.” Fortunately for both of us, this should

be the end of it.

!

xi

Vita

EDUCATION

2014 M.S.W., University of California, Los Angeles

1994 A.B. with Honors, Stanford University

Honors Thesis: An Intervention to Address Stereotype Threat: Changing Attitudes

About Intelligence. Advisors: Claude Steele, Joshua Aronson

PUBLICATIONS

Peer-Reviewed Articles

Abrams, L. S., Barnert, E. S., Mizel, M. L., Bryan, I., Lim, L., Bedros, A., Soung, P., & Harris,

M. (In press). Is a minimum age of juvenile court jurisdiction a necessary protection?

Lessons learned from the state of California. Crime and Delinquency.

Mizel, M. L., & Abrams, L. S. (2017). What I’d tell my 16 year old self: Criminal desistance,

young adults, and maturation. International Journal of Offender Therapy and

Comparative Criminology.

Mizel, M. L., Miles, J. N., Pedersen, E. R., Tucker, J. S., Ewing, B. A., & D'Amico, E. J. (2016).

To educate or to incarcerate: Factors in disproportionality in school discipline. Children

and Youth Services Review, 70, 102-111.

Abrams, L. S., Mizel, M. L., Nguyen, V., & Shlonsky, A. (2014). Juvenile reentry and aftercare

interventions: Is mentoring a promising direction? Journal of Evidence-Based Social

Work, 11(4), 404-422.

Policy Briefs and Technical Reports

Mizel, M. L., Barnert, E. S., Abrams, L. S. Bryan, I., Ridofli, L., Harris, M., Soung, P. (2017).

2015 California Data on Young Children in The Juvenile Justice System. Los Angeles,

CA: UCLA.

Davis, L. M., Tolbert, M. A., Mizel, M. L. (2017). Higher Education in Prison: Results from a

National and Regional Landscape Scan. Project Report, #PR-3123-GLHEC. Justice

Infrastructure and Environment (Justice Program) and Education. Santa Monica, CA:

RAND Corporation.

AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS

2017 – 2018 UCLA Dissertation Year Fellowship

2016 – 2017 Frank D. Gilliam Social Justice Award

2016 – 2017 Social Welfare Departmental Competitive Fellowship

2015 – 2016 UCLA Graduate Research Mentorship Fellowship

2014 UCLA Graduate Summer Research Mentorship Fellowship

2014 – 2015 Oliver M. Stone Scholarship

2013 – 2014 Oliver M. Stone Scholarship

2013 Shapiro Fellowship

2013 Bergman Fellowship

1994 Psi Chi, Psychology National Honor Society

1993 – 1994 Stanford University Honors Thesis Grant

!

xii

PRESENTATIONS

Peer-Reviewed Presentations

Mizel, M. L., & Abrams, L. S. (2018). Qualities of Successful Re-Entry Programs for Young

Men: A Focus Group Study. Paper presentation: Society for Social Work Research

Annual Meeting, January, 2018. Washington, D.C.

Mizel, M. L. (2017). Social psychological factors in pretrial decision making. Paper

presentation: American Society of Criminology Annual Meeting, November, 2017.

Philadelphia, PA.

Mizel, M. L., & Abrams, L. S. (2016). Practically emotional: What works with young men’s

desistance. Paper presentation: American Society of Criminology Annual Meeting,

November, 2016. New Orleans, LA.

Mizel, M. L. (2016). Teaching in the American incarceration system. Paper presentation:

American Society of Criminology Annual Meeting, November, 2016. New Orleans, LA.

Mizel, M. L., & Abrams, L. S. (2015). What I’d tell my 16 year old self: Criminal desistance,

young adults, and maturation. Paper presentation: American Society of Criminology

Annual Meeting, November, 2015. Washington, D.C.

Lopez, S. A., Mizel, M. L., Klomhaus, A., Comulada, W. S., Bath, E., Amani, B., & Milburn, N.

G. (2015). Emotional regulation, conduct problems, and resilience among newly

homeless youth with trauma symptoms: the role of individual, family, and communal

factors. Poster presentation: American Psychological Association Annual Convention,

August, 2015. Toronto, Canada.

Invited Presentations

Abrams, L. S., & Mizel, M. L. (2018). From research to policy: How one good idea can

influence state law. Invited pre-conference workshop: Society for Social Work Research

Annual Meeting, January, 2018. Washington, D.C.

Mizel, M. L. (2015). To educate or to incarcerate: Factors in disproportionality in school

discipline. Paper Presentation: RAND Corporation. Santa Monica, CA.

RESEARCH EXPERIENCE

2017 – Graduate Student Researcher, UCLA

Present A Case Study of the Minimum Age of Juvenile Court Jurisdiction in California.

PI: Laura Abrams, Ph.D., Department of Social Welfare.

Co-PI: Liz Barnert, MD, MPH, MS, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine.

2016 – 2017 Summer Associate and Adjunct Staff, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

A National Scan of Postsecondary Prison Education.

PI: Lois Davis, Ph.D., Senior Behavioral Scientist.

2015 – 2016 Summer Associate and Adjunct Staff, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Using the CHOICE Data to Analyze the School-to-Prison Pipeline.

PI: Elizabeth D’Amico, Ph.D., Senior Behavioral Scientist.

2014 – 2015 Graduate Student Researcher, UCLA

STRIVE: A Family-Based Intervention for Juvenile Justice Involved Youth.

PIs: Norweeta Milburn, Ph.D., and Eraka Bath, MD, UCLA David Geffen School

of Medicine

2014 – 2015 Graduate Student Researcher, UCLA

Re-entry and Recidivism for Young Adults in Los Angeles.

PI: Professor Laura Abrams, Department of Social Welfare.

!

1

Chapter One: Introduction

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an

impartial jury…to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for

obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.” –

Amendment VI to the United States Constitution (U.S. Const. amend VI)

Despite this statement in the Bill of Rights, today approximately 95% of all criminal

cases in the United States end in a plea bargain and not in a trial by jury, albeit with the

defendant’s consent (Hofer, 2011; Rosenmerkel, Durose, & Farole, 2009; Wright, 2005). This

was not the manner in which the American legal system initially operated as plea bargains were

rare until after the Civil War (Rakoff, 2014). They became much more common in the second

half of the 19

th

century and continued to increase throughout the 20

th

century (Fisher, 2000). In

the plea bargain process, the prosecution and defense negotiate the charges and punishment to

which the defendant pleads guilty, eliminating the jury trial. In exchange for the guilty plea, the

prosecutor offers a reduced charge and/or sentence (Smith & Levinson, 2012). Because

prosecutors set the initial charges, which often have mandatory minimum sentences, they have

greater leverage in the negotiations and, hence, more sentencing discretion than the defense

(Bibas, 2004; Hofer, 2011; Johnson, 2003).

In 2015, African Americans comprised 13% of the population of the United States

(United States Census Bureau, 2016). However, they made up 27% of those who were arrested

in 2015 (U.S. Department of Justice, 2016) and 36% of those in state or federal prison in 2014

(Carson, 2015). As African Americans move through the justice system, they experience

!

2

increasingly more punitive outcomes than the rest of the population. Not only are there racial

disparities in arrest rates, but these disparities persist through later stages of the criminal justice

system (Baumer, 2013). Yet until recently, scant research has focused on the pretrial component

of the judicial system (Baumer, 2013; Forst, 2010). This newer research has found evidence of

racial disparities even when controlling for both legal and extra-legal factors (Kutateladze, Lynn,

& Liang, 2012). These extralegal factors are defined as perceived characteristics of the

defendant and victim that are legally irrelevant, such as race (Hagan, 1973).

Consequences of Pretrial Decisions

Pretrial proceedings impact the outcome of a criminal case in several ways (Spohn,

2000; Ulmer, 2012). When the prosecutor determines the initial charges in a criminal case, this

frames all the subsequent pretrial (and potentially trial) proceedings. Initial charges serve as the

basis for bail, and defendants who are detained pretrial (because they are held without bail or do

not pay bail) are more likely to be incarcerated as a result of the case and receive longer

sentences, even when controlling for relevant legal factors (Albonetti, 1991; Baumer, 2013;

Spohn, 2015; Williams, 2003; Wooldredge, Frank, Goulette, & Travis, 2015; Zatz, 1987).

Charges are linked to recommended sentences and sometimes mandatory minimum sentences, so

the prosecutor has more influence over the potential sentence than the judge. A greater number

of charges are associated with longer post-conviction sentences (Shermer & Johnson, 2010;

Wilmot & Spohn, 2004). The increase in the number of charges that carry mandatory minimums

has enhanced the power of prosecutors, reducing the sentencing discretion available to judges

(Smith & Levinson, 2012). As a result, the prosecutor through setting the initial charges anchors

the negotiation for any subsequent plea bargaining (Bibas, 2004; Kang et al., 2012).

!

3

Pretrial decisions appear to contribute to racially disparate court outcomes that have

harmful consequences for African Americans relative to White defendants.

1

Recently, the

District Attorney of New York, the National Institute of Justice, and the Vera Institute

collaborated to study prosecutorial discretion in over 220,000 cases from New York City in

2010-2011. The researchers found that charge seriousness, prior record, and offense type, the

factors most relevant to the legal elements of a case, were the strongest predictors of case

outcomes (e.g., prison sentence). However, the defendant’s race was a statistically significant

correlate of case outcome even when accounting for the above legal factors. Across all offenses,

African American defendants were more likely to be detained than Whites at arraignment (i.e.,

remanded or have bail set and not met), to receive a custodial sentence as a result of the plea

bargaining process, and to be subsequently incarcerated (Kutateladze, Andiloro, Johnson, &

Spohn, 2014).

Additional studies have also found racial disparities in pretrial proceedings. Prosecutors

filed more charges against African American defendants and were less likely to offer them court

diversion programs (Bishop, Leiber, & Johnson, 2010; Martin, 2014; Schlesinger, 2013).

African Americans were more likely to be detained pretrial as a result of not being offered

release without bail or not paying bail (Demuth, 2003; Freiburger, Marcum, & Pierce, 2010;

Henning & Feder, 2005). Furthermore, African American defendants accepted plea deals that

were more likely to include incarceration and for longer periods of time (Johnson, 2003;

Kutateladze et al., 2014; Spohn & Fornango, 2009). Spohn (2009) found that race had an

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

!

1

!This dissertation focuses on African Americans and Whites, but certainly race is not a construct

with only two categories. This decision reflects the limited amount of research beyond these two

groups in the theoretical areas of this study, implicit racial bias and dehumanization bias. Future

research will expand beyond the African American/White binary.!

!

4

indirect effect on sentence severity through its effect on pretrial status resulting in worse

outcomes for African Americans. Furthermore, disparate treatment in pretrial proceedings

appear to be additive in producing disadvantage for African Americans in final case outcomes

(Baumer, 2013; Spohn, 2015; Wooldredge et al., 2015; Zatz, 1987).

Pretrial decisions augment entry into the justice system, which can have dramatic

consequences. Once an individual is declared guilty of a felony, whether by trial or plea bargain,

that person can lose rights and opportunities pertaining to voting, employment, housing,

education, public benefits, and jury service that relegates them to the status of second class

citizen (Alexander, 2012). For example, a felony drug conviction decreases: (1) access to jobs

and related health benefits, (2) access to public housing due to the 1996 policy initiative titled

One Strike and You’re Out, (3) access to health benefits such as food stamps due to PRWORA

(Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996), (4) access to jobs,

licenses/permits, and military service due to PRWORA, (5) access to financial supports for

higher education due to the Higher Education Amendments of 1998, (5) the right to vote in many

states (Iguchi, Bell, Ramchand, & Fain, 2005).

Pretrial detention can impact the lives of those accused of a crime regardless of the

outcome of their case. In a study of defendants who were released pretrial but at varying times,

those held in jail for three or more days were 2.5 times less likely to have employment after

release than those detained less than three days while controlling for relevant factors including

prior employment. In addition, those in jail for three or more days pretrial indicated a 40%

greater likelihood of residential instability than those detained less than 3 days (Holsinger, 2016).

Pretrial detention also has long-term economic implications as it appears to prevent individuals

from connecting with the formal employment sector. Controlling for baseline factors, defendants

!

5

released pretrial were 5% more likely to have employment within two years of the bail hearing

and 4% more likely to have any income than those detained pretrial. Three to four years after the

bail hearing, released defendants were 4% more likely to file a tax return and received 66% more

in the earned income tax credit. These results derived from those released being less likely to

have a criminal conviction and from being more likely to be employed in the formal job market.

Because pretrial detention was associated with criminal conviction even when controlling for

relevant legal factors, pretrial release was a factor in long-term employment and salary outcomes

(Dobbie, Goldin, & Yang, 2016).

These consequences may motivate innocent people to plead guilty to minor crimes

simply to get out of jail (Bibas, 2004; Van Cleve, 2016). In a study of bail in Philadelphia, the

effect of pretrial detention was not statistically significant for “strong-evidence” crimes (DUI,

drugs, illegal firearms) but was strong and significant for “weak-evidence” crimes (assault,

vandalism, and burglary). Those detained pretrial for a weak-evidence crime were 7% more

likely to plead guilty and averaged an additional 18 months of incarceration. These crimes have

higher rates of wrongful conviction, so these results suggest that pretrial detention increases the

likelihood that an innocent person will plead guilty (Stevenson, 2016). In addition, as

prosecutors can overcharge to set the parameters of the criminal proceedings and a potential plea

bargain negotiation, doing so can motivate innocent defendants to plead guilty to even a serious

crime to avoid a lifetime imprisonment or death penalty sentence (Alexander, 2012; Blume &

Helm, 2014; Redlich, 2016). Of the 1,793 people exonerated in the United States between 1989

and September 1, 2016, 283 of them (15.8%) had pled guilty. Of them, 122 (43.1%) were

African American, and 102 were (36.0%) White. Those 283 exonerated people had been

convicted of the following crimes: homicide (42%), sexual assault (26%), other violent crimes

!

6

(14%), and non-violent crimes (18%) (The University of Michigan Law School, 2016). This

suggests that pretrial proceedings may lead to innocent people pleading guilty to avoid a worse

outcome (Rakoff, 2014), and that this may disproportionally impact African Americans.

Pretrial Decision Making and Social Work

Most of our clients are people who have crawled their way up from poverty or are in the

throes of poverty. Our clients work in service-level positions where if you’re gone for a

day, you lose your job. People in need of caretaking — the elderly, the young — are left

without caretakers. People who live in shelters, where if they miss their curfews, they

lose their housing. Folks with immigration concerns are quicker to be put on the

immigration radar. So when our clients have bail set, they suffer on the inside, they

worry about what’s happening on the outside, and when they get out, they come back to a

world that’s more difficult than the already difficult situation that they were in before.

— Scott Hechinger, a senior trial attorney with Brooklyn Defender Services (Pinto, 2015)

This suffering while in jail and its prolonged aftereffects are a few of the consequences for many

of those detained pretrial awaiting the adjudication of their criminal case. As previously

described and will be elaborated further, pretrial detention is not equal across racial groups.

Moreover, detention is only one element of pretrial proceedings that impacts those in the

criminal justice system and that has racial disparities. Therefore, the social problem of

differential treatment of African Americans during pretrial criminal proceedings in the justice

system is important to social work. The Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social

Workers defines the role of social work as follows:

The primary mission of the social work profession is to enhance human well-being and

help meet the basic human needs of all people, with particular attention to the needs and

!

7

empowerment of people who are vulnerable, oppressed, and living in poverty. A historic

and defining feature of social work is the profession’s focus on individual well-being in a

social context and the well-being of society. Fundamental to social work is attention to

the environmental forces that create, contribute to, and address problems in living.

(National Association of Social Workers Delegate Assembly, 2008)

The goal of this study is to enhance human well-being by identifying and measuring racial bias

in the legal system, which can serve as a step towards reducing unjust treatment of African

Americans. More specifically, African Americans experience disproportionally harsher

treatment in pretrial proceedings, resulting in more punitive outcomes. This impact on human

well-being includes increased likelihood of being detained pretrial, increased hardship upon

release pretrial, and increased likelihood of receiving a worse plea deal. This study addresses

social justice for those who are “vulnerable, oppressed, and living in poverty” (National

Association of Social Workers Delegate Assembly, 2008). Not only does this social problem

impact African Americans as a group, but it also affects the individual well-being of the

defendant in the social context of the justice system and the social context of race.

This dissertation is designed to be the first study in a series concerning pretrial decision

making. The early studies will identify which psychological processes are factors in pretrial

decision making and attempt to determine their contribution to racial disparities. In so doing,

that information will provide a road map to the cognitions that shape the way prosecutors make

determinations, suggesting which ones need to be addressed to reduce racial disparities.

Subsequent studies will then test interventions to lessen the impact of those biases, hopefully

reducing racial disparities. The implementation of those interventions is an opportunity

especially suited for social workers, because they are skilled in affecting attitude and behavior

!

8

change on the micro level as well as modifying systems and organizations on the macro level. In

addition, through both training and experience, social workers are knowledgeable about racial

disparities and social justice, providing them with the background to execute such challenging

work. Finally, this would present social work with an opportunity to have a seat at the justice

system table, which has been lacking in recent years (Abrams, 2013).

The story of Kalief Browder elucidates the potential impact of pretrial decision making

and its relevance to social work. On May 15, 2010, New York City police arrested 16-year-old

Browder for allegedly stealing a backpack and punching a man in the face. He was charged as

an adult with robbery, grand larceny, and assault, and the judge set bail at $3,000. His family

could not afford the $300 bond to post bail, so Browder was sent to the jail at Rikers Island. He

stayed there for over 1,000 days awaiting trial as the Bronx court system was overbooked and

slow. While Browder was confined at Rikers, both guards and other detainees beat and abused

him, including one brutal attack caught on security cameras that appeared on news outlets.

Browder spent approximately two of those three years at Rikers in solitary confinement. He

tried to commit suicide six times but never received mental health treatment. In January, 2013,

Browder was offered release on time served if he pled guilty to two misdemeanors. His other

option was to go to trial where he faced a possible 15-year prison term. Browder refused to take

the plea deal, maintaining his innocence. On May 30, 2013, after 31 pretrial court dates, the

prosecution dropped the case because the victim had returned to Mexico. Browder was released

at the age of 20. Two years later on June 6, 2015, Browder committed suicide. According to

those who knew him, he had not seemed to recover from his detention at Rikers (Gonnerman,

2014; Schwirtz & Winerip, 2015). Although Browder’s story had a more tragic outcome than

!

9

most, it exemplifies some of the impacts of pretrial proceedings and the dangers of pretrial

detention. The decisions made by prosecutors can have very powerful consequences.

Prior Approaches to Racial Disparity in Pretrial Decision Making

Scholars have primarily used the focal concerns perspective to analyze pretrial decision

making. According to this perspective, three focal concerns guide the thinking of prosecutors

when making case decisions: (1) the defendant’s blameworthiness and the harm caused to the

victim, (2) the protection of the community, and (3) the likelihood of conviction (Spohn,

Beichner, & Davis-Frenzel, 2001; Steffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer, 1998). First, prosecutors

seek greater punishment for the defendant based on the defendant’s culpability and the severity

of the harm to the victim. Second, the pretrial process is part of the legal system that aims to

prevent the defendant from harming the community in the future as well as deterring others from

committing crime (Steffensmeier et al., 1998). Third, prosecutors focus on the likelihood of

conviction based on the ways that the defendant, the victim, and the incident will be evaluated by

the judge and potential jurors (Spohn et al., 2001). Prosecutors balance these complicated focal

concerns while working with incomplete information about the defendants and the cases. To

address such uncertainties as determining which defendants are dangerous, they enlist a

“perceptual shorthand” that can include attributions based on such a characteristic as race

(Farrell & Holmes, 1991; Steffensmeier et al., 1998).

Prosecutors exercise discretion in six ways in the pretrial process: the initial

screening/charging, pretrial release/bail, dismissal, charge reduction, plea bargaining, and

sentencing constraints (Kutateladze et al., 2012). With each, they make subjective evaluations

with limited information, and many of those decisions require an assessment of the defendant.

Research suggests that at each of those pretrial steps prosecutors utilize racial stereotypes to

!

10

make determinations about the defendant’s culpability and danger to the community.

Prosecutors combine both legally relevant factors about the case and the defendant with

extralegal defendant characteristics as they balance the three focal concerns in their pretrial

decision making. As a result, factors such as charge seriousness, prior record, and offense type

are associated with pretrial decisions and case outcomes, but race is a factor, too (Kutateladze et

al., 2014).

Innovations of This Dissertation

Although the focal concerns perspective provides insight into the factors that shape

pretrial decision making, it does not fully address the process of racial bias. Two theories from

social psychology, implicit racial bias and dehumanization bias, provide insight into the

functioning of race in judgement and decision making that could provide greater explanatory

nuance, potentially buttressing the focal concerns perspective. According to implicit bias theory,

unconscious attitudes and stereotypes, including about race, influence human thought and

behavior (Blair, 2002; Greenwald & Krieger, 2006; Kang et al., 2012; Rudman, 2004). Implicit

racial bias factors into perceptions of a defendant’s guilt and potential danger, because implicit

associations exist between African Americans and such cognitions as culpability (Graham &

Lowery, 2004), hostility (Devine, 1989), and possessing weapons (Eberhardt, Goff, Purdie, &

Davies, 2004; Nosek, Smyth, et al., 2007). Therefore, implicit racial bias may influence pretrial

prosecutorial discretion through charging decisions, particularly whether to charge and for what

crimes, and strategy, including bail recommendations and plea bargain negotiations (Smith &

Levinson, 2012). Despite the extensive research about implicit racial bias during the last 30

years, scholars have not measured its role in pretrial decision making.

!

11

Dehumanization bias is a process through which people perceive a person or group as

less than human (Haslam, 2006) and exists in both implicit and explicit forms (Haslam &

Loughnan, 2014). People with high implicit dehumanization bias are more likely to perceive

African American youth as older than their chronological age, and therefore, believe them more

culpable for a crime. In addition, police officers who indicated on measures a greater implicit

dehumanization bias against African Americans more frequently used higher levels of force

against them in actual police records (Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta, & DiTomasso, 2014).

Accordingly, dehumanization bias may influence pretrial decision making, because explicit

dehumanization of a defendant predicted recommending longer sentences and less support for

rehabilitation efforts (Viki, Fullerton, Raggett, Tait, & Wiltshire, 2012). Infrahumanization is a

more subtle form of dehumanization in which people associate secondary emotions, such as

sympathy and jealousy, with being human (Demoulin et al., 2004; Leyens et al., 2003; Leyens,

Demoulin, Vaes, Gaunt, & Paladino, 2007). Infrahumanization could influence legal decision

making; for example, it has been associated with being less likely to forgive others for past

violence (Tam et al., 2007; Wohl, Hornsey, & Bennett, 2012). As with implicit racial bias, prior

research has not tested whether dehumanization bias is a factor in pretrial decision making.

Although research has documented racial disparities in pretrial decision making, this

dissertation is the first known study to test whether implicit racial bias and dehumanization bias

are factors in pretrial decision making. To do so, this study will measure racial bias (both in

implicit and explicit forms) and dehumanization bias (also in both implicit and explicit forms) to

assess the influence of each. Only a few studies have simultaneously assessed whether implicit

racial bias and dehumanization bias are factors in any outcome, so this methodology adds a layer

of innovation through its analysis. In conclusion, the purpose of this dissertation study is to

!

12

make a step forward in the understanding of the factors that contribute to racial disparities in

pretrial decision making.

Research Questions

This dissertation poses the following questions:

1. Are implicit racial bias, explicit racial bias, implicit dehumanization bias, and/or explicit

dehumanization bias associated with pretrial decision making (for each of initial charge,

bail, target plea sentence, minimum acceptable plea sentence, and charge reduction)?

2. What are the relative influences of implicit racial bias, explicit racial bias, implicit

dehumanization bias, and explicit dehumanization bias?

Hypotheses

The following hypothesized results answer the two research questions.

Research question #1: Implicit racial bias, explicit racial bias, implicit dehumanization

bias, and explicit dehumanization bias are predicted to be associated with pretrial decision

making in the following ways:

1. With an African American defendant, anti-African American/pro-White implicit racial

bias, explicit racial bias, implicit dehumanization bias, and explicit dehumanization bias

will be positively associated with more punitive initial charges, greater bail amounts,

longer target plea sentence, longer minimum acceptable plea sentence, and less charge

reduction.

2. With a White defendant, anti-African American/pro-White implicit racial bias, explicit

racial bias, implicit dehumanization bias, and explicit dehumanization bias will be

negatively associated with more punitive initial charges, greater bail amounts, longer

!

13

target plea sentence, longer minimum acceptable plea sentence, and less charge

reduction.

Research question #2: Implicit racial bias, explicit racial bias, implicit dehumanization

bias, and explicit dehumanization bias will have the following relative relationships within the

full model:

1. Implicit racial bias will be a significant factor in outcomes when controlling for explicit

racial bias.

2. Implicit dehumanization bias will be a significant factor in outcomes when controlling for

explicit dehumanization bias.

3. Implicit dehumanization bias will be a more powerful factor in outcomes than implicit

racial bias.

4. Explicit dehumanization bias will be a more powerful factor in outcomes than explicit

racial bias.

5. Explicit racial bias will be the weakest predictor for outcomes.

Overview of Dissertation

Chapter Two will examine the current state of knowledge about racial disparities in

pretrial decision making through a comprehensive literature review. It will identify the six steps

in pretrial decision making in which prosecutorial discretion shapes the direction of the case.

The evidence about whether racial disparities exist in each of those steps will be assessed. The

dominant theoretical explanation for how prosecutors make decisions, namely the focal concerns

perspective, will be reviewed. Finally, the chapter will include an assessment of the research to

identify the gaps in the understanding of racial disparities in pretrial decision making.

!

14

In Chapter Three, the paper will introduce research on implicit racial bias and

dehumanization bias and their possible roles in pretrial decision making. These theories will be

used to identify the dissertation research questions and the hypotheses about their answers. In

Chapter Four, the participants in the research study will be described, including the criteria for

inclusion. The research materials needed for the study will be identified and detailed along with

the procedure for the experiment. Finally, the analytic procedure that will be used to determine

the results based on the data will be described. Chapter Five will detail the results of the study

based on the statistical analyses. Chapter six, the final chapter of the dissertation, will conclude

with a discussion of the results. Each research question will be answered, and the results will be

placed into the context of the research in the field.

!

15

Chapter Two: Literature Review

Overview of Chapter

This chapter will begin with a description of the mechanics of the pretrial process and

provide additional background information on pretrial detention. Next, the chapter will define

the six areas in which prosecutorial discretion shapes pretrial decision and review the research on

racial disparities within these areas. The impact of these steps on case outcomes, a process

known as cumulative disadvantage, will be detailed to further elucidate the role of race in the

pretrial process. The focal concerns perspective, which is the most commonly used framework

to explain pretrial decision making, will be described as well as evidence in support of it.

Finally, gaps in the literature will be identified.

Pretrial Procedure

Criminal court processes vary slightly between state and federal jurisdictions as well as

among local courts, but the overarching structure functions in a similar manner. After arrest, the

first formal court appearance is an arraignment, during which the filing prosecutor represents the

people. The defendant first hears all the charges against him or her and has the opportunity to

enter a plea. The three most common pleas are not guilty, guilty, and nolo contendere, referred

to as "no contest.” Those who enter a plea of guilty or no contest proceed to a sentencing

hearing. Most people plead “not guilty,” so a judge then determines the conditions for pretrial

release, if appropriate. Defendants can be released without financial conditions or assigned a

bail amount to pay to secure release. A non-financial release can take one of three forms: own

recognizance, unsecured bond, and conditional release. With a release on own recognizance, the

defendant agrees to appear in court in the future as required. A financial release, also called bail,

can be paid in four different ways. Defendants most commonly pay bail through a surety bond in

!

16

which a bail bonds company signs a promissory note for the full amount to the court and the

defendant pays a fee that is normally equal to 10%. The bond company usually requires

collateral, and this fee is not refunded even if the defendant is exonerated or charges are dropped.

A judge sets the bail amount after receiving a recommendation from the prosecutor and a rebuttal

from the defense. Prosecutors base their suggestion on a combination of discretion and a

schedule that takes into account the current criminal charges and the defendant’s prior criminal

history. In setting bail, the judge considers the risk of flight and the need to protect public safety.

Some states, such as New Jersey and Alaska, do not charge money bail for most defendants but

instead use a risk assessment tool to determine whether to release pretrial (Doyle, 2017). Other

states are considering this approach, including California.

The next step in the pretrial process is the preliminary hearing during which the handling

prosecutor takes over the case from the filing prosecutor. In special prosecutor units, such as

white collar or gang crimes, one prosecutor may handle the entire case. The judge hears

evidence to determine whether probable cause exists to believe that a crime occurred and that the

defendant committed it. If so, the case is sent to trial. It may take days, months, or years to

begin a trial. At any point from arraignment up until the verdict in the trial, the prosecution and

defense can agree to a plea deal. During the pretrial proceedings, several rounds of negotiation

may occur. In a plea agreement, the defendant pleads guilty and waives the right to trial in

exchange for reduced charges and/or punishment, including a shorter sentence.

Background on Pretrial Detention and Bail

Pretrial detention refers to keeping a defendant confined from arrest until disposition,

which is the final legal determination of the case, in order to ensure appearance in court and/or

preventing him or her from committing another crime (Stevenson, 2016). In mid-year 2014,

!

17

American jails confined 744,600 people, of which 467,500 (63%) were being held pretrial. The

total population was slightly less than the peak of 785,500 inmates at mid-year 2008, but since

2000, the jail inmate population has increased by 123,500 from 621,149. Importantly, 95% of

that growth was from those being held pretrial. During the entire year period ending on June 30,

2014, jails admitted 11.4 million people. White inmates represented 47% of the total jail

population, African Americans accounted for 35%, and Latino/as comprised 15% (Minton &

Zeng, 2015).

Many jail detainees have not been denied bail but rather have not paid it. In the most

recent survey of the 75 most populous counties in 2009, 38% of felony defendants were detained

until case disposition, but only 10% of those had been denied bail. They were unable to meet

bail despite the median amount being $10,000, which would have required $1,000 payment for a

bond (Reaves, 2013). Of defendants in Philadelphia whose bail was less than or equal to $500,

only 51% were able to pay the $50 deposit required for release within the three days after arrest,

and 25% remained detained at disposition (Stevenson, 2016). From 1990 to 2009, the

percentage of pretrial releases that enlisted financial conditions rose from 37% to 61%, including

an increase from 24% to 49% in the use of bail bond company’s surety bonds (Reaves, 2013).

Bail costs in most cases are not extremely high, but rather the act of being required to pay bail

prevents most people from obtaining pretrial release. In effect, monetary bail itself denies

release (Demuth, 2003).

Research shows that defendants who are detained pretrial resolve their cases sooner and

are more likely to be found guilty. In data from the 75 most populous counties, the median time

for detained defendants from arrest to adjudication (determination of guilt or innocence) was 69

days with a 77% conviction rate; for those released it was 163 days with a 59% conviction rate

!

18

(Reaves, 2013). Overall, an increasingly large number of Americans are held in jail pretrial as a

result of not paying the financial requirements for release. Because defendants who reside in jail

pretrial are more likely to settle their case sooner and to plead guilty, the monetary cost of bail

impacts a criminal case beyond pretrial detention.

Prosecutorial Discretion

Prosecutors have full discretionary power, and oversight comes from within the

department. They set the charges, have the power to dismiss them, and have the ability to reduce

initial charges to lesser counts. Prosecutors use this power along with the ability to reduce

sentencing recommendations during plea bargain negotiations, and in the vast majority of cases

judges accept the negotiated plea deal without revision (Bibas, 2009). As a result, prosecutors

have a powerful influence over criminal punishment (Shermer & Johnson, 2010). Kutateladze et

al. (2012) defined the steps in which prosecutorial discretion operates:

• Initial screening—the prosecutor determines whether to accept a case for prosecution and

the initial charges to file;

• Pretrial release or bail procedure—the prosecutor recommends whether a defendant is

detained in jail while the case is pending and whether to offer bail and at what amount;

• Guilty plea—the prosecutor negotiates any plea bargain

• Sentencing—the prosecutor’s prior pretrial decisions affect the type and length of

punishment for a convicted person;

• Dismissal—the prosecutor decides whether a case or charge is dismissed at any point

after the initial screening; and

• Charge reduction—the prosecutor determines if the severity or the amount of charges are

reduced.

!

19

Dismissal and charge reduction are less likely to occur, and charge reduction within the context

of a plea negotiation is addressed within plea bargain research. As a result, few studies examine

dismissal and charge reduction. In addition, they are also both extremely difficult to study

methodologically because of the limited amount of available data on them. Given their smaller

presence in the pretrial process, this project will focus on the other four steps.

Sentencing guidelines provide recommendations for incarceration length for convictions

on charges. Lawmakers have expanded them in both the state and federal criminal justice

systems over the past 40 years, and as a result the conviction charge has a great influence over

the sentence length. This is particularly true due to the increase in mandatory minimum

sentences, which set incarceration terms that judges must follow. Simultaneously, sentencing

regulations have moved from indeterminate (punishment offered a range of time incarcerated

that could be shortened with parole) to determinate (those convicted received a set release date

often followed with no supervision/parole in the community), which also confines judges’

choices. This combination of an increase in sentencing guidelines and determinate sentencing

has constrained the role of the judge and placed more power with the prosecutors (Ball, 2006;

Shermer & Johnson, 2010; Spohn, 2000; Tonry, 1996; Wilmot & Spohn, 2004). In a 1996

survey of federal judges and chief probation officers before many sentencing guidelines had been

implemented, 86% agreed (and 57% strongly agreed) that “sentencing guidelines give too much

discretion to prosecutors.” In addition, 75% of judges and 59% of chief probation officers

thought that the prosecutor had “the greatest influence on the final guideline sentence” (Johnson

& Gilbert, 1997). The power that prosecutors hold in setting and negotiating charges has a great

influence on punishment and functions as the discretion previously held by judges (Piehl &

!

20

Bushway, 2007). The following sections review the research on racial disparities where

prosecutorial discretion operates.

Appropriate Legal Factors

It is important to recognize that despite existing racial disparities in pretrial decision

making, research consistently finds that relevant legal factors have the greatest bearing on

pretrial proceedings and sentencing. Numerous studies have reported that charge severity and

prior criminal history of the defendant are the strongest factors in predicting pretrial detention. A

more violent crime and a larger number of charges are associated with an increased likelihood of

pretrial detention. Researchers consistently find a similar positive relationship for criminal

history, which can be measured as prior arrests and/or prior convictions. Prior arrests can reflect

racial disparity, though, as African Americans are more likely to be arrested and have charges

dismissed (Kutateladze et al., 2014). Other legally relevant elements can play a role, too. If the

offense occurred while the defendant was on probation or parole, he or she was more likely to be

detained pretrial (Reitler, Sullivan, & Frank, 2013). Harm to the victim can also be a factor in

increased likelihood of pretrial detention (Wooldredge et al., 2015). Spohn (2009) found that

pretrial detention was less likely when those accused had more education, were employed, and

were married. In total, these results are consistent with the criteria that are considered legally

relevant for determining whether to detain in jail someone accused of a crime. According to

§3142(g) of the Bail Reform Act of 1984, judges are to consider the nature of the offense, the

offender’s past conduct and current legal status, the offender’s financial resources, and the

offender’s family ties, employment, and community ties (Spohn, 2009). These factors

consistently appear in studies as predictors of pretrial detention. Moreover, this pattern

continues with sentencing, because crime severity and criminal history are commonly the two

!

21

strongest predictors (Kramer & Ulmer, 2009). While relevant legal factors increase the odds of

pretrial detention and more punitive sentencing, the subsequent sections provide evidence that

race can also be a factor in prosecutorial discretion.

Initial Screening/Charging

During the initial screening/charging, the prosecutor decides whether to prosecute the

case based on the evidence and then determines the charges to file. Research on initial screening

suggests that prosecutors are more likely to pursue stronger legal action against African

American defendants than Whites. One of the first choices for a prosecutor is whether to offer

pretrial diversion. In this process, the prosecutor defers or dismisses a charge as long as the

defendant successfully completes a community-based diversion program, allowing the defendant

to avoid a criminal record. In a nationally representative sample of cases from 1990 to 2006,

prosecutors offered this option primarily for drug-use crimes and for those without a prior

conviction, occurring in 8% of all cases. African Americans had 28% lower odds of receiving

pretrial diversion than Whites with similar legal characteristics. Among drug defendants with no

prior record, African Americans had 43% lower odds of pretrial diversion than Whites

(Schlesinger, 2013). Based on juvenile court case files over a period of 21 years (1980 through

2000) in one county in a Midwestern state (n = 5,722), prosecutors were more likely to refer

African American than White youth to juvenile court than release or send them to a court

diversion program (Bishop et al., 2010). Thus, in these two studies prosecutors were more likely

to decide to charge an African American defendant criminally as opposed to offer diversion from

court.

If diversion is not offered, prosecutors determine the extent to charge a defendant, which

may also be influenced by the defendant’s race. Examining cases where the defendant was

!

22

accused of murder in Chicago from 1994-1995 (n = 672), Martin (2014) included the

race/ethnicity (African American, Latino, and White) of both the defendant and the victim.

African American defendants charged with killing White victims were prosecuted more severely

(received more charges) than all other defendant–victim pairings. Conversely, African American

defendants charged with killing African Americans and Latino/as charged with killing Latino/as

were prosecuted the least severely. This suggests that the race of the defendant and the victim, at

least in cases of murder, may influence prosecutors’ charging behavior (Martin, 2014).

Moreover, in a study in Minnesota of over 4,000 felony convictions, prosecutors were more

likely to charge African Americans more severely across all crimes (Miethe, 1987). These

charging disparities can have an important effect as African Americans are more likely to plead

guilty if more charges are filed while Whites are less likely (Albonetti, 1990). Rehavi and Starr

(2014) found evidence for the downstream effect of initial charge when looking at federal cases

from 2006-2008 in which African American and White men were arrested for violent,

property/fraud, weapons, and public order offenses. Courts punished African Americans with

sentences 10% longer than comparable White defendants, and most of the disparity derived from

prosecutor’s initial charging decisions. Prosecutors were 1.75 times more likely to file charges

that carried mandatory minimum sentences with African American defendants, which explained

more than half of the difference in sentencing (Rehavi & Starr, 2014).

However, research on domestic violence has produced conflicting results on the role of

race in charging. In a study of 2,948 misdemeanor assault cases against an intimate partner in

Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio during 1993, 1995, and 1996, prosecutors were more likely

to drop a case against African Americans than Whites even after controlling for socioeconomic

status variables (i.e., education, employment, public assistance, residential stability, and

!

23

household composition) (Wooldredge & Thistlethwaite, 2004). In a different analysis of 4,178

domestic violence cases (both misdemeanor and felony) in a Tennessee county, though,

prosecutors were more likely to dismiss the case for White defendants than people of color (98%

of whom were African American) while controlling for income and employment (Henning &

Feder, 2005). It is possible that the variation in results appeared due to the difference in the

sample (misdemeanor versus misdemeanor and felony) or in the included control variables.

Overall, these studies provide evidence that African Americans are more likely to be

charged for a crime when referred for prosecution. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that

additional extralegal factors may influence prosecutor decision making, such as socioeconomic

status or race of the victim. This first decision in pretrial is important because it establishes the

direction of the case and sets boundaries for the ultimate case outcome. With federal cases,

charging carries particular weight due to the greater number of sentencing guidelines.

Regardless of the jurisdiction, the initial charges constrain future options in sentencing through

both plea bargain and judicial judgment (Shermer & Johnson, 2010).

Pretrial Release and Bail

Among felony defendants from state court in the 75 most populous counties in 1990,

1992, 1994, and 1996, African Americans were 66% more likely to be detained pretrial than

Whites, even when controlling for type of crime and prior criminal history. It is important to

note that African American and White defendants received the same average bail amount, but

African Americans were less likely to pay that bail. Their odds of detention were double when

assigned bail. The strongest predictor of being released on bail was the amount; higher bail

associated with a lower likelihood of release. Including gender in the analysis, White women

were the least likely to be detained while African American men were 18.3% more likely to be

!

24

held pretrial than all other defendants (Demuth & Steffensmeier, 2004). Additional studies of

data sets of existing cases found that African American defendants were less likely than white

defendants to be released on their own recognizance (Freiburger et al., 2010; Henning & Feder,

2005). In total, these studies suggest that African American and White defendants on average

receive the same bail settings but that the impact was disparate: African Americans were more

likely to remain in jail pretrial.

Examining race alone without other demographic variables may only paint a partial

picture, though. For example, race itself was not a factor in an Ohio jurisdiction, but when the

interaction of race, gender, and age was analyzed, African American men age 18-29 were less

likely to be released on one’s own recognizance, had higher bail amounts, and had a greater

likelihood of incarceration in comparison to other groups (Wooldredge, 2012). This study is one

of many about pretrial decisions that will be detailed in this proposal that did not find a main

effect for race but reported an interaction of race, gender, and age. This intersectionality does

not undermine that race is a factor but rather reveals that the effect of race can vary with those

other demographic or identity factors (Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall, 2013).

Guilty Plea/Plea Bargaining

As stated earlier, 95% of criminal cases are settled with a plea bargain (Hofer, 2011;

Rosenmerkel et al., 2009; Wright, 2005). Stemen (2016) found that 76% of guilty pleas do not

involve a charge reduction, indicating defendants often plead to the most severe charge.

Defendants who are people of color are 18% more likely to plead guilty than Whites. Young

people of color and men are more likely to plead guilty than all other groups (Stemen, 2016). In

a study of misdemeanor marijuana cases in New York City, African American defendants were

less likely to receive reduced charge offers and more likely to receive plea offers with custodial

!

25

punishment compared to White defendants. In the final model that included the most legal

factors, evidence, arrest circumstances, and court actor characteristics, race became non-

significant. However, the authors argued that those factors in themselves were racially biased

(e.g., African Americans were more likely to have an arrest history from the “stop-and-frisk”

policy) (Kutateladze, Andiloro, & Johnson, 2016). These two studies examined plea bargaining

separately from other parts of the pretrial process. In the later section of this chapter about

cumulative disadvantage, additional research about plea bargains will be reviewed and provides

more conclusive information on racial disparities.

Sentencing

Both federal and state justice systems have sentencing guidelines for criminal convictions

on specific charges that provide a minimum and maximum term of incarceration. Prosecutors

apply mandatory minimums much less often when defendants plead guilty in a plea bargain;

those who are convicted at trial are more likely to receive a mandatory minimum sentence.

Prosecutors seem to negotiate away the mandatory minimum charge or sentence in exchange for

a guilty plea. Importantly, this implies that prosecutors use the threat of a longer mandatory

minimum sentence as leverage in plea bargain negotiations (Ulmer, Kurlychek, & Kramer,

2007). In the pretrial process, enhancement charges can be added to the list of offenses. In a

study in Maryland of violent offenses (n = 19,995), African Americans were 9% more likely to

be assessed a firearm penalty; it resulted on average in an additional 41 months of prison

(Farrell, 2003). In Florida, a defendant can be classified as a Habitual Offender and receive

sentencing enhancements if they have two prior felony convictions and the current conviction

was committed either while serving a Department of Corrections sentence or within 5 years of a

prior conviction. Of all those eligible to be an Habitual Offender, African Americans were 22%

!

26

more likely than Whites to be classified as one (Caravelis, Chiricos, & Bales, 2011).