NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

845

GETTING TO THE GOOD PLACE: IMPLEMENTING NEW JERSEY’S

MEDICAL AID IN DYING FOR THE TERMINALLY ILL ACT

Megan Nigro

*

I. INTRODUCTION

In 2019, New Jersey approved an aid in dying bill and joined several

states that have expanded legal end of life choices to include forms of

physician-assisted death. New Jersey’s Medical Aid in Dying for the

Terminally Ill Act (hereinafter “the Act”) raises interesting questions

about patient choice, but some patients have not been able to use this

choice since the Act became effective on August 1, 2019. Robin Granat,

a former singer and ice skater, diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor,

made an appointment for August 19, 2019, to make her first request for

the aid in dying medication.

1

Before the appointment, a Mercer County

court had already placed a temporary restraining order on the Act.

2

A

few days later, Robin lost her ability to speak and could not make her

first oral request as required by the Act.

3

Other New Jersey patients

have used or still hope to use the Act. Katie Kim, a former pharmacist,

diagnosed with an incurable neuromuscular disorder eight years prior,

wanted to move to a state with an aid in dying law, but her doctors were

*

J.D. Candidate, 2021, Seton Hall University School of Law; B.A., 2018, Wake Forest

University. Many thanks to Professor Carl Coleman for his guidance and to Tracy

Forsyth, Deputy General Counsel at University Hospital, for her support in pursuing this

topic.

1

Lindy Washburn & Stacey Barchenger, She Hoped for Death on Her Own Terms.

Then NJ’s Aid-In-Dying Law Was Challenged, NORTH JERSEY REC. (Aug. 30, 2019, 5:30 AM),

https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/new-jersey/2019/08/30/nj-aid-dying-

law-challenge-prevents-woman-with-brain-cancer-from-ending-life-on-her-own-

terms/2123105001/.

2

Id. The temporary injunction on the use of the Act had been removed, but the

lawsuit continued. Stacey Barchenger, New Jersey’s ‘Aid-in-Dying’ Law Reinstated After

a Pair of Court Rulings, TRENTON BUREAU (Aug. 27, 2019, 10:53 AM), https://www.north

jersey.com/story/news/2019/08/27/nj-aid-dying-law-reinstated-appeals-court/212

9382001. The doctor suing argued that the Act as a whole was unconstitutional, and he

objected to turning over patient records in compliance with the Act. Id. In 2020, the

judge dismissed the case for “failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted.”

Glassman v. Grewal, No. MER-C-53-19 (N.J. Super. Ct. Ch. Div. Apr. 1, 2020) (order

granting dismissal of complaint).

3

Washburn & Barchenger, supra note 1.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

846 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

all in New Jersey.

4

When New Jersey allowed a similar choice, she hoped

to use the law to help her die in peace.

5

Within the first several weeks

of the Act, at least one New Jersey resident used the Act to request and

self-administer medication to end her suffering.

6

Zebbie Geller, a retired

teacher, was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer nine months prior

and was told she had only months left to live.

7

From July 2019 to her

death at the end of September 2019, Zebbie and her family contacted 40

doctors before they could find physicians willing to aid in Zebbie’s

death.

8

At eighty-years-old and while surrounded by family, Zebbie

swallowed an anti-nausea pill and apple juice mixed with digoxin, “a

cardiac drug that slows the heart,” and died within 90 minutes.

9

Zebbie’s story depicts how the Act was made to work. Zebbie met the

standard requirements, physicians could personally object to aid in her

dying, and Zebbie could request and self-administer her own

medication.

10

This Comment discusses considerations for implementation for

New Jersey doctors and facilities on behalf of New Jersey patients who

want to participate in successful aid in dying stories like Zebbie’s. As

readers consider this Comment, they should think about these patients

and the myriad of other patients who might choose to request or use aid

in dying medication. This Comment will not discuss whether New Jersey

patients should have the right to make this choice. This Comment will

examine other states and countries where patients have similar end of

life options and make suggestions for New Jersey safeguards and best

practices so the Act may best serve its purpose in providing patients

with this end of life choice and protecting against unintended

consequences and abuse.

While the Act does promise to give patients more choice while

protecting them from coercion, abuse, or neglect, and is partially

modeled after statutes in other states, this Comment argues that New

Jersey can learn from other states and countries in its implementation

4

Susan K. Livio, She Wants to End Her Life Because of Agonizing Pain. ‘Every Day

Katie Asks Me to Help Her Die.’, N.J. ADVANCE MEDIA (Aug. 23, 2019), https://www.nj.com/

news/2019/08/she-wants-to-die-because-of-agonizing-pain-from-incurable-disease-

but-law-that-gave-hope-is-stalled.html.

5

Id.

6

Susan K. Livio, N.J. Woman Used New Law to End Her Life. ‘I’m Ready, Let’s Do It.’, N.J.

ADVANCE MEDIA (Oct. 18, 2019), https://www.nj.com/news/2019/10/nj-woman-used-

new-law-to-end-her-life-im-ready-lets-do-it.html.

7

Id.

8

Id.

9

See id.

10

See id.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 847

and application while considering its unique population and statutory

definitions. Part II introduces the Act and the statutory language

describing the self-administration, residency, and time between

requests requirements and discusses initial concerns with the

definitions and language. Part III analyzes and compares other states’

and countries’ definitions of the three requirements discussed in this

Comment, with an emphasis on the self-administration requirement.

Part IV compares usage and implementation based on a statistical

analysis of census data and state aid in dying reports. Part V converts

these comparisons into considerations for New Jersey’s implementation

and best practices.

II. DEFINITIONS IN NEW JERSEY’S MEDICAL AID IN DYING FOR THE TERMINALLY

ILL ACT

This Part introduces New Jersey’s Medical Aid in Dying for the

Terminally Ill Act and explains three definitions from the Act: self-

administer, resident, and time between requests.

A. Introduction to the Act

In April 2019, after seven years of proposed legislation,

11

Governor

Murphy signed New Jersey’s Medical Aid in Dying for the Terminally Ill

Act.

12

While Governor Murphy grappled with the ethical questions

raised by this legislation, he ultimately wanted New Jersey residents to

have the freedom to make their own end of life choices.

13

The Act itself

states its purpose to continue the state’s “long-standing commitment to

individual dignity, informed consent, and the fundamental right of

competent adults to make health care decisions.”

14

Under the Act, only specific adults will be eligible to make aid in

dying their end of life choice.

15

The Act defines a qualified terminally ill

patient as follows:

[A] capable adult who is a resident of New Jersey and has

satisfied the requirements to obtain a prescription for

medication pursuant to P.L.2019, c.59 (C.26:16-1 et al.). A

11

To read more about the years of legislation, see New Jersey, COMPASSION & CHOICES,

https://compassionandchoices.org/in-your-state/new-jersey/#extended-state-

content (last visited Oct. 29, 2019).

12

Philip D. Murphy, Governor’s Statement Upon Signing Assembly Bill No. 1504 (Apr.

12, 2019), http://d31hzlhk6di2h5.cloudfront.net/20190412/4b/cd/8b/1f/02854e1f1

393a35250679633/A1504.pdf.

13

Id.

14

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-2 (2019), https://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2018/Bills/PL19/

59_.PDF.

15

§ 26:16-1 to 20.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

848 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

person shall not be considered to be a qualified terminally ill

patient solely because of the person’s age or disability or a

diagnosis of any specific illness, disease, or condition.

16

Furthermore, “‘[t]erminally ill’ means that the patient is in the terminal

stage of an irreversibly fatal illness, disease, or condition with a

prognosis, based upon reasonable medical certainty, of a life expectancy

of six months or less.”

17

A qualified patient must make three requests

before an attending physician can prescribe aid in dying medication.

18

The Act provides a sample written request form for patients to use as

one of the three requests.

19

The attending physician must also refer the

qualified patient to a consulting physician who may confirm the physical

diagnosis and the patient’s capability to make an informed and

voluntary decision.

20

If either physician has questions or concerns

about a patient’s mental capability, that physician must refer the patient

to a mental health care professional.

21

The Act clarifies twice that any

health care professional or patient who takes action under the Act does

not participate in euthanasia, suicide, assisted suicide, or homicide.

22

Therefore, this Comment respectfully refers to the actions taken under

the Act as furthering aid in dying but uses other states’ and countries’

respective terms, such as euthanasia, when discussing those

jurisdictions’ laws.

B. Defining and Applying Self-Administration

In New Jersey’s statute, “‘[s]elf-administer’ means a qualified

terminally ill patient’s act of physically administering, to the patient’s

own self, medication that has been prescribed pursuant to” the Act.

23

This language impliedly excludes any patient who may otherwise

qualify for the Act but lacks enough physical strength or coordination to

administer their own medication. This may include patients who had an

existing physical disability limiting strength or coordination before

acquiring a terminal illness and becoming otherwise eligible for the Act.

The Act could also exclude a patient who, through the time it takes to

complete the Act’s requirements, loses her strength and ability to self-

administer medication. Remember that Zebbie Geller needed enough

16

§ 26:16-3.

17

Id.

18

§ 26:16-10.

19

§ 26:16.

20

§ 26:16-6.

21

§ 26:16-8.

22

§ 26:16-15, -17.

23

§ 26:16-3.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 849

control of her limbs and head to take a pill and drink a medication.

24

The

Act, however, does not explicitly state that a patient must ingest (rather

than inject) medication, but the requirements discussed herein imply an

expectation that a patient would have the physical ability to ingest the

medication.

Further analysis of the Act demonstrates how the term “self-

administer” imposes certain physical eligibility requirements for

patients beginning with the first request. A patient must complete a

valid written request for the aid in dying medication.

25

A valid written

request must be initialed, signed, and dated by the patient.

26

The Act

requires a patient to have enough physical strength and coordination to

initial, sign, and date a document. The same hypothetical patient

discussed above, who had a physical disability before terminal illness or

who acquired a physical disability since diagnosis of a terminal illness,

could be excluded even before consideration of whether that patient can

physically self-administer if that patient physically cannot complete the

required written request.

C. Defining and Applying Residency

Under the Act, the attending physician who would ultimately

prescribe the aid in dying medication must require the patient to

demonstrate New Jersey residency.

27

The patient must provide the

physician with a copy of:

a. a driver’s license or non-driver identification card issued by

the New Jersey Motor Vehicle Commission;

b. proof that the person is registered to vote in New Jersey;

c. a New Jersey resident gross income tax return filed for the

most recent tax year; or

d. any other government record that the attending physician

reasonably believes to demonstrate the individual’s current

residency in this State.

28

This language allows for a person who previously lived in New

Jersey but currently resides across the accessible borders of New York

or Pennsylvania to continue to utilize a New Jersey driver’s license to

easily access the Act. In becoming a terminally ill patient, a person could

utilize a license with her hometown address to access the Act while

residing in New York City. Patients with terminal illnesses may not have

24

See Livio, supra note 6.

25

§ 26:16-5.

26

§ 26:16-20.

27

§ 26:16-6.

28

§ 26:16-11.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

850 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

the strength or ability to change states.

29

But an inability to travel

because of a need for particular doctors or lack of strength may be made

easier by the physical proximity of New Jersey’s neighboring states. Part

(d) of the residency definition leaves room for physician discretion in

determining residency.

30

As applied by an attending physician, this

discretionary portion could work either in favor of or against patient

access to aid in dying medication. A physician could reasonably find

residency in (d) even when a patient may not be a New Jersey resident.

A patient who is a resident of New Jersey may only have (d)

documentation but be denied legitimate access to the Act because of the

physician’s discretionary determination of residency. While physicians

are always allowed to refuse to participate in aid in dying,

31

patients

without an ID, voter registration, or a most recent tax return might feel

a sense of injustice if their request is denied for lack of such

documentation. Residency seems like it should be a simple checkmark

in the Act’s requirements, but entire court cases can dispute a person’s

residency in one or multiple locations.

32

D. Defining and Applying Time Between Requests

Under the Act, patients and physicians must follow a minimum

timeline for making requests and writing prescriptions.

33

The timeline

requires that:

(1) at least 15 days shall elapse between the initial oral

request and the second oral request; . . .

(3) the patient may submit the written request to the

attending physician when the patient makes the initial oral

request or at any time thereafter; . . .

(5) at least 15 days shall elapse between the patient’s initial

oral request and the writing of a prescription pursuant to

P.L.2019, c.59 (C.26:16-1 et al.); and

(6) at least 48 hours shall elapse between the attending

physician’s receipt of the patient’s written request and the

writing of a prescription . . . .

34

In applying the quickest scenario possible, a patient could submit an oral

and written request on Day One, wait fifteen days, submit a second oral

request on Day Sixteen, and receive a prescription to self-administer the

29

See, e.g., Livio, supra note 4.

30

§ 26:16-11.

31

See § 26:16-3.

32

See generally Sheehan v. Gustafson, 967 F.2d 1214 (8th Cir. 1992).

33

§ 26:16-10.

34

Id.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 851

same day.

35

But if a patient waits until his second oral request on Day

Sixteen to provide a written request, then the attending physician must

wait until at least Day Eighteen to write the prescription.

36

A clear

reading of the Act does not impose a maximum time limit between

patient requests. A qualified terminally ill patient could make an initial

request in January 2021, survive past a six-month prognosis, and make

the second oral request with a written request in January 2022. Under

the Act, the patient has not re-started the aid in dying process.

Additionally, the Act does not set a maximum amount of time between

an attending physician receiving oral and written requests and writing

a prescription for medication.

37

The lack of maximum time between requests will become an issue

when trying to evaluate the efficiency of implementation under the Act.

While attending physicians are required to document all requests,

38

an

attending physician is only required to report the dispensing

medication record and the death record to the Department of Health for

statistical purposes.

39

Therefore, the public data of the Act will only

show two points in the aid in dying process; thus, limiting New Jersey’s

understanding of average time spent considering and completing this

end of life option. If a purpose of the Act is to increase patient choice in

treatment, then New Jersey should understand the length of time a

patient takes to make and implement treatment choices.

III. IMPLEMENTATION AND COMPARISON OF OTHER STATES’ AND COUNTRIES’

AID IN DYING LAWS

In the United States, individual states can enact statutes to create

an ability for physicians and patients to participate in aid in dying, but

states may also explicitly ban any physician-assisted death without

violating the Constitution.

40

Even as applied to competent, terminally ill

adult patients,

41

the federal Constitution does not protect a patient’s

access to aid in dying medication.

42

In Washington v. Glucksberg, the

35

See id.

36

See id.

37

See id.

38

§ 26:16-10(d).

39

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-13.

40

See Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 728, 735 (1997).

41

This is one of four scenarios where a person may wish to accelerate death. The

other three are suicide of a non-terminally ill person or patient, withdrawal of life

support of a terminally ill patient, and physician active euthanasia of a terminally ill

patient. See NOAH R. FELDMAN & KATHLEEN M. SULLIVAN, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 595 (20th ed.

2019).

42

See Glucksberg, 521 U.S. at 735.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

852 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

Supreme Court concluded that past precedent allowing patients to deny

unwanted, life-sustaining treatment does not transform into a right to

assisted suicide.

43

Furthermore, it held that the right to personal

autonomy under the Due Process Clause of the federal Constitution does

not extend to every possible personal decision.

44

This Part will compare

the self-administration, residency, and time between request

requirements in New Jersey to those requirements in other states and

countries.

A. Definitional Comparisons of United States Statutes

In Oregon, patients have access to medication to hasten death

through the state’s Death with Dignity Act.

45

In 1994, citizens voted in

the act by a small margin, but then an injunction stalled the process until

1997 when a second vote to keep the legislation resulted in the law’s

enactment.

46

Oregon Health Authority has been collecting data since

that year.

47

Oregon’s act does not provide specific language for a self-

administration requirement.

48

It does, however, require a written

request signed and dated by a qualified patient,

49

which suggests a need

for the patient to have a level of physical strength and control, similarly

required for physical self-administration in New Jersey.

50

The Oregon

Health Authority does clarify that a patient must self-administer and

that a physician may not administer.

51

Oregon’s residency requirement

provides a list of acceptable documentation, such as a driver’s license,

voter registration, and tax return,

52

but leaves discretion, like in New

Jersey’s act, by allowing other documentation. Additionally, the ability

for a person to show he leases property as documentation

53

may allow

for a non-resident to meet this requirement. Oregon required fifteen

days between the first request and a prescription and 48 hours between

43

See id. at 725–26. The Court references its discussion of removing treatment in

Cruzan v. Director, Missouri. Dept. of Health, and of ending life in Vacco v. Quill. Id.

44

See id. at 727–28. The Court references its discussion of right to abortion in

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey. Id.

45

Frequently Asked Questions: Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, OR. HEALTH AUTHORITY,

https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRE

SEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Pages/faqs.aspx (last visited Nov. 1, 2020).

46

Id.

47

See id.

48

OR. REV. STAT. §§ 127.800–127.897 (1994).

49

§ 127.810-2.02.

50

See supra text accompanying note 23.

51

Frequently Asked Questions: Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, supra note 45.

52

OR. REV. STAT. § 127.860-3.10.

53

Id.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 853

a written request and prescription

54

and, like New Jersey, did not set a

maximum time period between requests. But a change to Oregon law in

2019 allowed Oregon patients to bypass the fifteen-day waiting period

if they are expected to die within the fifteen days.

55

In California, qualified terminally ill patients can request aid in

dying medication through the End of Life Option Act.

56

California’s

history in allowing aid in dying as an end of life option began, in part,

with a patient named Brittany Maynard.

57

At twenty-nine-years-old,

Brittany was diagnosed with a brain tumor but with an otherwise

healthy body and expected a lengthy, painful death.

58

After doing some

research about her treatment options, she chose to use aid in dying

medication, but that option was unavailable in California.

59

Brittany

moved to Oregon, found new doctors, and established residency to

qualify for Oregon’s act.

60

She received the aid in dying medication in

Oregon but kept fighting for a change in California’s law and end of life

options.

61

Under the California act, an aid in dying drug is specifically defined

as a drug an individual can self-administer,

62

and “‘[s]elf-administer’

means a qualified individual’s affirmative, conscious, and physical act of

administering and ingesting the aid-in-dying drug to bring about his or

her own death.”

63

California also explicitly requires that an individual

must have the physical ability to self-administer,

64

and reinforces these

physical requirements by mandating (a) a request form signed and

dated by the patient;

65

and (b) a final attestation form signed, initialed,

and dated by the patient 48 hours before the patient self-administers.

66

Notably, California’s act explicitly prohibits a person who is present at

54

§ 127.850-3.08.

55

The Oregonian/OregonLive Politics Team, New Law Shortens ‘Death with Dignity’

Waiting Period for Some Patients, OREGONIAN (July 24, 2019), https://www.oregon

live.com/politics/2019/07/new-law-shortens-death-with-dignity-waiting-period-for-

some-patients.html.

56

End of Life Option Act, CAL. DEP’T PUB. HEALTH, https://www.cdph.ca.gov/

Programs/CHSI/Pages/End-of-Life-Option-Act-.aspx (last visited Nov. 1, 2020).

57

See Brittany Maynard, COMPASSION & CHOICES, https://compassionandchoices.org/

stories/brittany-maynard (last visited Nov. 1, 2020).

58

Id.

59

See id.

60

Id.

61

See id.

62

CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE § 443.1 (West 2015).

63

Id.

64

§ 443.2.

65

Id.

66

§ 443.5, .11.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

854 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

the time of death from helping a patient ingest the medication.

67

Overall,

California’s language and requirements surrounding self-

administration are more explicit than those in New Jersey’s act. New

Jersey lacks any language describing how a patient must ingest a

medication and does not specifically reinforce the physical strength

needed near the time of self-administration through a final attestation

form, as California’s act does.

Unlike New Jersey, California does not allow for any unlisted forms

of identification to show residency.

68

California’s requirement does,

however, allow for a patient to demonstrate residency through a leased

property,

69

similar to Oregon’s residency requirement.

70

California’s

requirement of a minimum of fifteen days between requests, but no

maximum number of days,

71

parallels New Jersey’s requirement.

72

California does, however, add a maximum time of 48 hours for a patient

to complete a final attestation form and self-administer the aid in dying

drug.

73

New Jersey’s law contains no similar temporal limitation.

In Washington state, patients can access aid in dying medication

through the Death with Dignity Act.

74

The law was approved by voters

in 2008 after a ballot initiative campaign launched in 2005 with the

support of Oregon funds and advisers; then, it became effective in March

2009.

75

Washington’s act clarifies that self-administration must be

through an act of ingesting medication.

76

In Washington, a qualified

patient must sign and date a written request;

77

this suggests the same

level of physical strength and ability to self-administer under the New

Jersey act, which does not explicitly say that a patient must ingest aid in

dying medication. Washington’s residency requirement allows for

unlisted documentation outside the options and allows for a patient to

show leased property as evidence of residency.

78

These broad options

allow for more residency options than the acts in New Jersey, Oregon,

67

CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE § 443.14.

68

§ 443.2.

69

Id.

70

OR. REV. STAT. § 127.860-3.10.

71

CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE § 443.3.

72

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-10.

73

CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE § 443.5.

74

Death with Dignity Act, WASH. ST. DEP’T HEALTH, https://www.doh.wa.gov/Youand

YourFamily/IllnessandDisease/DeathwithDignityAct (last visited Oct. 31, 2019).

75

Washington, DEATH WITH DIGNITY, https://www.deathwithdignity.org/states/

washington (last visited Sept. 18, 2019).

76

WASH. REV. CODE § 70.245.010 (2008).

77

§ 70.245.090.

78

§ 70.245.130. Options to show residency include a state driver’s license, voter

registration, and owning or leasing property in the state. Id.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 855

and California. The fifteen days required between oral requests and 48

hours required from a physician receiving a written request and writing

a prescription

79

match New Jersey’s time between requests

requirements.

80

In Colorado, terminally ill patients can access aid in dying

medication pursuant to Colorado’s End-of-Life Options Act,

81

which

voters approved in 2016.

82

Colorado requires a qualified patient to

make an informed decision to self-administer.

83

“‘Self-administer’

means a qualified individual’s affirmative, conscious, and physical act of

administering the medical aid in dying medication to himself or herself

to bring about his or her own death.”

84

This language is similar to the

California law but, like New Jersey’s statute, it fails to explicitly require

that a patient ingest the medication. Colorado also requires a patient to

sign and date a written request,

85

which, like New Jersey’s requirement,

reinforces the requirement of the patient’s physical ability to self-

administer. Unlike New Jersey, Colorado only allows for the listed

documentation options to prove residency, but one of these options

includes showing a leased property in the state.

86

Colorado requires

fifteen days between oral requests

87

but, unlike New Jersey, does not

add an additional forty-eight-hour waiting period between the patient

making the written request and the physician writing the prescription.

Patients in Maine recently gained access to aid in dying with

Maine’s Death with Dignity Act.

88

The state legislature voted in the act

in Spring 2019, and Governor Janet Mills signed it into law in June

2019.

89

In Maine, a qualified patient may self-administer by “voluntarily

ingest[ing] medication to end the qualified patient’s life in a humane and

dignified manner.”

90

This language differs from New Jersey’s approach

by specifically requiring a patient to ingest the medication. Like New

Jersey and other states, the Maine act requires the patient to have the

79

§ 70.245.090, .110.

80

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-10.

81

Medical Aid in Dying, COLO. DEP’T OF PUB. HEALTH & ENV’T, https://www.colorado.

gov/pacific/cdphe/medical-aid-dying (last visited Oct. 31, 2019).

82

Id.

83

COLO. REV. STAT. § 25-48-102 (2016).

84

Id.

85

§ 25-48-104; see also § 25-48-112.

86

§ 25-48-102.

87

§ 25-48-104.

88

Paula Span, Aid in Dying Soon Will Be Available to More Americans. Few Will Choose

It., N.Y. TIMES (July 8, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/08/health/aid-in-

dying-states.html.

89

Id.

90

ME. REV. STAT. ANN. tit. 418, § 2140(2)(L) (2019).

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

856 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

physical capacity to sign and date a written form.

91

Maine’s residency

requirement offers the longest list of options for documentation of

residency and gives the most detail in what the documentation can and

cannot show.

92

The residence of a person is that place where the person has

established a fixed and principal home to which the person,

whenever temporarily absent, intends to return. The following

factors may be offered in determining a person’s residence

under this Act and need not all be present in order to

determine a person’s residence: A. Possession of a valid

driver’s license issued by the Department of the Secretary of

State, Bureau of Motor Vehicles; B. Registration to vote in this

State; C. Evidence that the person owns or leases property in

this State; D. The location of any dwelling currently occupied

by the person; E. The place where any motor vehicle owned

by the person is registered; F. The residence address, not a

post office box, shown on a current income tax return; G. The

residence address, not a post office box, at which the person’s

mail is received; H. The residence address, not a post office box,

shown on any current resident hunting or fishing licenses held

by the person; I. The residence address, not a post office box,

shown on any driver’s license held by the person; J. The receipt

of any public benefit conditioned upon residency, defined

substantially as provided in this subsection; or K. Any other

objective facts tending to indicate a person’s place of

residence.

93

Unlike other states, Maine’s other evidence option relies more on

objective facts of residency than other forms of identification.

Additionally, the “need not all be present” phrase can prompt physicians

to consider multiple forms of identification, which other states,

including New Jersey, have failed to recommend.

94

While Maine’s

residency requirements are unique, its waiting period requirements for

a minimum of fifteen days between oral requests

95

and 48 hours from a

patient writing a request and the physician writing a prescription

96

parallel the requirements in New Jersey and the majority of the states

discussed infra.

91

§ 2140(5).

92

§ 2140(15).

93

Id. (emphasis added).

94

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-11.

95

ME. REV. STAT. ANN. tit. § 2140(11) (2019).

96

§ 2140(13).

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 857

B. Aid in Dying Around the World: A Comparison of New Jersey and

United States Requirements with International Requirements

In Belgium, competent adults and emancipated minors gained

access to hasten their death pursuant to The Belgian Act on Euthanasia

on May 28, 2002.

97

These persons must be patients “in a medically futile

condition of constant and unbearable physical or mental suffering that

can not [sic] be alleviated, resulting from a serious and incurable

disorder caused by illness or accident.”

98

In 2014, Belgium removed its

previous age limit; thus, the country radically extended its law to allow

children of any age to request the lethal injection as long as the parents

give consent.

99

Since then, physicians have euthanized seventeen-,

eleven-, and nine-year-old patients.

100

Rather than requiring patients to

self-administer, Belgium allows euthanasia, which it defines as a

physician—not the patient—terminating the patient’s life.

101

The default requirements under Belgian law do assume some level

of patient physical strength and ability. Similar to New Jersey and other

United States acts, Belgium’s act requires a patient to write and sign a

request.

102

Unlike in New Jersey and the United States, however,

Belgium provides an exception where a patient may designate a person

to write and sign the request if the person lists why the patient is

incapable of independently writing a request.

103

Therefore, Belgium

does not necessarily restrict patients who are physically disabled from

their illness or a previous condition from access to euthanasia, whereas

New Jersey and other states restrict these patients from access to aid in

dying options.

Additionally, Belgium’s act does not contain residency

requirements.

104

Further, Belgium’s equivalent of the time between

requests requirements offers more discretion than New Jersey or other

97

Belgium, PATIENTS RTS. COUNCIL, http://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/

belgium (last visited Sept. 19, 2019).

98

§ 1 [The Belgian Act on Euthanasia] of May 28, 2002, 10 EUR. J. HEALTH L. 329

(2003).

99

Belgium, PATIENTS RTS. COUNCIL, http://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/

belgium (last visited Nov. 13, 2020). Note that while technically the child makes the

decision, it is easy to imagine the technical lines blurring between a child making a

decision and a parent making a decision but a child expressing it as her own.

100

Dale Hurd, The ‘Default Way to Die’: Are Dutch and Belgian Doctors Euthanizing

People Who Don’t Want to Die?, CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING NETWORK (Aug. 28, 2019),

https://www1.cbn.com/cbnnews/world/2019/april/euthanasia-becoming-default-

way-to-die-in-belgium.

101

§ 1 [The Belgian Act on Euthanasia] of May 28, 2002.

102

§ 3(4) (Belg.).

103

Id.

104

See [The Belgian Act on Euthanasia] of May 28, 2002.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

858 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

United States laws. The act requires physicians to engage in “several”

conversations with the patient about the patient’s request and physical

and mental suffering over a “reasonable period of time.”

105

Belgium’s

act is clear, however, in requiring at least one month between the

written request and euthanasia if the “physician believes patient is

clearly not expected to die in the near future.”

106

One month between a

written request and death is longer than New Jersey’s 48 hours,

107

but

the above language leaves the physician some discretion and an ability

to euthanize even before 48 hours have elapsed.

Even though Belgium does not require a maximum time between

requests and death, Belgium does cap advance directives for euthanasia;

still, people who may not be mentally competent at the time of

administration may access Belgium’s act.

108

If the patient’s euthanasia

request comes as an advance directive, the directive will only be valid if

it was drafted in the last “five years prior to the person’s loss of the

ability to express his/her wishes.”

109

In 2019, developments to Canada’s aid in dying law offered some

compelling justifications for why a state or country should allow

advance directives for medically assisted dying.

110

Members of Canada’s

legislative body recognize that Alzheimer’s patients are in a unique

position: when they are first diagnosed, they may be able to consent to

medical assistance in dying, but they are not at the required “end of

life.”

111

But, when an Alzheimer’s patient is near the end of life, they

have lost their ability to make a decision about medical assistance in

dying.

112

This legislative debate follows the Lamb case, where the court

expanded what it means for a patient’s death to be “reasonably

105

§ 3(2) (Belg.).

106

§ 3(3) (Belg.).

107

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-10.

108

§ 4(1) (Belg.). “[A]n advance directive, a legal document that goes into effect only

if you are incapacitated and unable to speak for yourself. This could be the result of

disease or severe injury—no matter how old you are. It helps others know what type of

medical care you want.” NAT’L INST. ON AGING, Advance Care Planning: Healthcare

Directives, U.S. DEP’T HEALTH & HUM. SERVS., https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/advance-

care-planning-healthcare-directives#after (last visited Jan. 9, 2020).

109

§ 4(1) (Belg.).

110

See Quebec to Expand Law on Medically Assisted Dying, Look at Advance Consent,

CBC NEWS (Nov. 29, 2019 9:34 AM), https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/

medical-assistance-in-death-report-1.5377890.

111

See id.

112

See id. See infra pp. 870–72, for an explanation of why New Jersey should not use

advance directives for aid in dying.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 859

foreseeable.”

113

The Supreme Court ruled against the current legislative

members’ understandings of “reasonably foreseeable” and in favor of a

patient-centered definition where “patients can meet the ‘reasonably

foreseeable’ criterion if they have demonstrated a clear intent to take

steps to make their natural death happen soon or to cause their death to

be predictable.”

114

The case could expand the current understanding of

the legislation to allow for advance directives, which may not require

informed consent at the time of request and the time of either

euthanasia or self-administration.

115

An advance directive could mean

the patient has lost his capacity to make informed consent by the time

he is requesting or receiving aid in dying treatment. Canada already

allowed patients with dementia, who still understand the requests they

are making, to be capable of the required informed consent.

116

Since 2002, doctors in the Netherlands have been legally allowed

to perform euthanasia on patients or assist in their suicides, even if the

patients do not have a terminal illness.

117

By 2015, 4.5% of deaths in the

Netherlands were caused by acts of euthanasia, with non-terminally ill

patients being a small portion of that percentage.

118

In 2018,

committees reviewed cases of euthanasia to compile resources and

guidance for physicians in the Euthanasia Code 2018.

119

In addition to

the lack of minimum or maximum time required between requests and

death,

120

the Netherlands act is not concerned with a specific prognosis.

It only requires that a patient’s suffering be “lasting and unbearable.”

121

113

Jocelyn Downie, A Watershed Month for Medical Assistance in Dying, POL’Y OPTIONS

POLITIQUES (Sept. 20, 2019), https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/september-

2019/a-watershed-month-for-medical-assistance-in-dying.

114

See id.

115

See Medical Assistance in Dying, GOV’T OF CAN., https://www.canada.ca/en/health-

canada/services/medical-assistance-dying.html (last visited Feb. 14, 2020).

116

See, e.g., The Sunday Edition, B.C. Man Is One of the First Canadians With Dementia

to Die with Medical Assistance, CBC RADIO (Oct. 27, 2019), https://www.cbc.ca/radio/

thesundayedition/the-sunday-edition-for-october-27-2019-1.5335017/b-c-man-is-

one-of-the-first-canadians-with-dementia-to-die-with-medical-assistance-1.5335025.

117

The Associated Press, Euthanasia Deaths Becoming Common in Netherlands, CBS

NEWS (Aug. 3, 2017), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/euthanasia-assisted-suicide-

deaths-netherlands.

118

Id.

119

Euthanasia Code 2018, REGIONAL EUTHANASIA REV. COMM. (Jan. 10, 2019),

https://english.euthanasiecommissie.nl/the-committees/documents/publications/

euthanasia-code/euthanasia-code-2018/euthanasia-code-2018/euthanasia-code-

2018.

120

Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (Review Procedures) Act

2001, 137. Art. 2(1)e (Neth.), https://www.worldrtd.net/dutch-law-termination-life-

request-and-assisted-suicide-complete-text.

121

See id. at Art. 2(1)b (Neth.).

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

860 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

Netherlands’ act does not contain language requiring a patient to

administer his own medication. Rather, in the Netherlands, doctors can

give a lethal injection to a person with unbearable suffering and no

reasonable alternative.

122

In its first criminal investigation of

euthanasia, the Netherlands court cleared a doctor of any criminal

charges for administering a sedative and lethal injection to a dementia

patient who exhibited mixed signals about wanting to die.

123

The

patient in this case, and like many other reported cases in the

Netherlands, had an advanced directive for euthanasia, and the doctor

had to perform that directive with due care.

124

At first glance, this case seems like the result of the “slippery slope”

people might be wary of and that United States laws want to protect

against by allowing only patients to self-administer their prescribed aid

in dying medications. But the doctor or the patient administering is not

the only distinction in this case. Even if states allowed for physician

administration, patients and health care professionals would not face

the issues seen in the Netherlands case. In that case, the patient had an

advance directive for euthanasia, like the law in Belgium allows and

possible changes to the law in Canada would allow;

125

no United States

statute, however, allows advance directives for aid in dying medication.

The Netherlands patient was not able to change her mind at the time of

administration, and the doctor ignored her mixed signals because of her

dementia.

126

A New Jersey case would never reach this point—even if

physicians could administer or prepare injections—because New Jersey

further requires the qualified patient to be capable and “hav[e] the

capacity to make health care decisions and to communicate them to a

health care provider, including communication through persons

familiar with the patient’s manner of communicating if those persons

are available.”

127

Given the symptoms of dementia,

128

it does not seem

122

Palko Karasz, Dutch Court Clears Doctor in Euthanasia of Dementia Patient, N.Y.

TIMES (Sept. 11, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/11/world/europe/

netherlands-euthanasia-doctor.html. For more recent examples of Dutch courts

allowing physicians to euthanize patients with dementia, see Another Netherlands Court

Approves Euthanasia by Advance Directive, MED. FUTILITY BLOG (Sept. 14, 2020),

http://www.bioethics.net/2020/09/another-netherlands-court-approves-euthanasia-

by-advance-directive.

123

See Karasz, supra note 122.

124

See id.

125

See supra pp. 857–59.

126

See Karasz, supra note 122.

127

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-3.

128

“Dementia is the loss of cognitive functioning—thinking, remembering, and

reasoning—and behavioral abilities to such an extent that it interferes with a person’s

daily life and activities. These functions include memory, language skills, visual

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 861

like many qualified terminally ill patients with dementia would be

deemed capable to make this health care decision.

129

Even if a physician

found an otherwise qualified terminally ill patient with early-stage

dementia capable under the New Jersey act, the patient would not have

the ability to make an advance directive for when the dementia

progresses and would always have the ability to rescind a request

regardless of his patient’s previous wishes.

130

New Jersey’s lack of a

maximum time between requests would allow the patient to complete

the request process very early in the stages of dementia, then, wait to

take the medication.

In Western Australia, patients gained access to aid in dying with the

Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill.

131

As the Victorian Voluntary Assisted

Dying Act 2017 became effective in June 2019, another Australian state,

Western Australia, was developing legislation in its parliament for its

own Voluntary Assisted Dying Act.

132

As Western Australia continued

developing legislation, an Australian woman became the first to use

Victoria’s new law.

133

After a twenty-six-day approvals process,

terminal cancer patient Kerry Robertson died at a nursing home.

134

Of all these international sources, Western Australia’s

requirements and safeguards for administration of medication,

residency, and timing of requests most closely parallel those used across

the United States, so New Jersey could implement some of Western

Australia’s safeguards. Furthermore, Western Australia’s act allows

United States health departments to draw more exact international

comparisons about aid in dying and consider cross-cultural

explanations for differences in trends. It is more challenging to compare

numbers across countries’ sets of data when the countries allow

perception, problem solving, self-management, and the ability to focus and pay

attention.” Nat’l Inst. of Aging, What Is Dementia? Symptoms, Types, and Diagnosis, U.S.

DEP’T HEALTH & HUM. SERVS., https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-dementia-

symptoms-types-and-diagnosis (last visited Jan. 9, 2020).

129

But see The Sunday Edition, supra note 116.

130

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-6(8).

131

See Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2019 (WA) (Austl.), https://www.parliament.wa.

gov.au/Parliament/Bills.nsf/502E87F2E1B94E27482584A3003A757C/$File/Bill139-

2.pdf; see also Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2019, PARLIAMENT W. AUSTL.,

https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/bills.nsf/BillProgressPopup?openFor

m&ParentUNID=502E87F2E1B94E27482584A3003A757C (last visited Jan. 10, 2020).

132

Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Lindy Willmot & Ben P. White, Regulating Voluntary

Assisted Dying in Australia: Some Insights from the Netherlands, MED. J. AUSTL. (Sept. 9,

2019), https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2019/211/10/regulating-voluntary-

assisted-dying-australia-some-insights-netherlands#4.

133

Assisted Dying: Australian Cancer Patient First to Use New Law, BBC NEWS (Aug. 5,

2019), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-49230903.

134

Id.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

862 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

patients of different ages and categories, such as minors or non-

terminally ill patients, to access aid in dying options.

135

Even though the Western Australian bill was modeled after the

Victorian act, it differs in its definition of acceptable administration

methods.

136

In Western Australia, self-administration is the default

option for a patient receiving medication.

137

A patient with a six-month

prognosis

138

can make the decision to have her physician administer the

substance if the physician has certain qualifications to be an

administering practitioner, including specific training.

139

A patient may

choose to self-administer or to have the practitioner administer the

medication.

140

Patients have an equal ability to choose between

practitioner administration or self-administration, but the provision

requires that practitioner administration should only be used when it

would be impossible or inappropriate for a patient to self-administer.

141

This language strikes a balance between (a) an emphasis on patients

taking their own voluntary assisted death actions and (b) a conscious

inclusion of patients who may lack physical ability but who are identical

to other patients in every other requirement. The signed, written

declaration requirement

142

suggests that patients using the law must

have the physical ability to self-administer, as New Jersey’s act requires.

But, as Belgium’s act requires,

143

an Australian patient who is unable to

sign the declaration can have another person sign the declaration on her

135

In other words, current cross-cultural comparisons are limited because of the

certain requirements in other countries. For example, if data trends showed patients in

Belgium spending five years between request and administration and New Jersey

patients show an average of six months between request and administration, it would

be hard to infer that this has something to do with the culture of healthcare in either

country because Belgium, unlike New Jersey, does not require a six-month prognosis but

does allow advance directives. A data analyst trying to infer cultural differences

between any/all U.S. states and Western Australia could be more confident in that

comparison because the similarities between the laws means eliminating differing

requirements that would otherwise be intervening variables.

136

Frances Bell, Voluntary Euthanasia Bill to Be Introduced into West Australian

Parliament, ABC NEWS (Aug. 6, 2019), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-06/

voluntary-assisted-dying-bill-introduced-to-wa-parliament/11386512.

137

Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2019 (WA) pt 4 div 2 s 56 (Austl.),

https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/Parliament/Bills.nsf/502E87F2E1B94E27482584

A3003A757C/$File/Bill139-2.pdf.

138

Id. pt 2 s 16. But a twelve-month prognosis is required for neurodegenerative

illness. Id.

139

Id. pt 4 div 1 ss 54–55.

140

Id. s 56.

141

See id.

142

Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2019 (WA) pt 3 div 5 s 42.

143

§ 3(4) [The Belgian Act on Euthanasia] of May 28, 2002.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 863

behalf.

144

The default option encourages a patient’s physical ability to

self-administer, but the exception allows a patient with a physical

disability from a previous condition or the terminal illness to still access

voluntary assisted dying. Physically disabled patients in New Jersey and

across the United States, however, are not granted these exceptions for

providing written documentation or for self-administration.

Western Australia’s residency requirement is based on objective

facts about residency in the prior year, rather than specific

documentation.

145

The most notable part of this requirement is the

specific ability of a patient to appeal to the Western Australian residency

decision from either the coordinating or consulting physician to a

tribunal.

146

New Jersey does not specifically allow for this type of

external, non-medical professional appeals process. Western Australia

only requires nine days between the first and final request for voluntary

assisted dying

147

and allows for an exception to the minimum nine days

if, among other requirements, the coordinating physician believes “the

patient is likely to die, or to lose decision-making capacity in relation to

voluntary assisted dying, before the end of the designated period.”

148

While New Jersey does not currently allow for physicians and patients

to hasten this process, future amendments should mirror the exceptions

in the Western Australian act and the amended Oregon act.

149

IV. STATISTICAL COMPARISON OF NEW JERSEY AND OTHER STATES AND

COUNTRIES

This Part reviews aid in dying data from other states and countries

discussed in this Comment, compares it with United States census data,

and makes predictions about how providers and patients could use New

Jersey’s act. This Part also considers data-reporting concerns similar to

those in other states and concerns unique to New Jersey.

144

Id.

145

See id. pt 2 s 16.

146

Id. pt. 5 sec. 84.

147

Id. pt. 3 div. 6 sec. 47.

148

Id. pt. 3 div. 6 sec. 47.

149

See OregonLive Politics Team, supra note 55.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

864 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

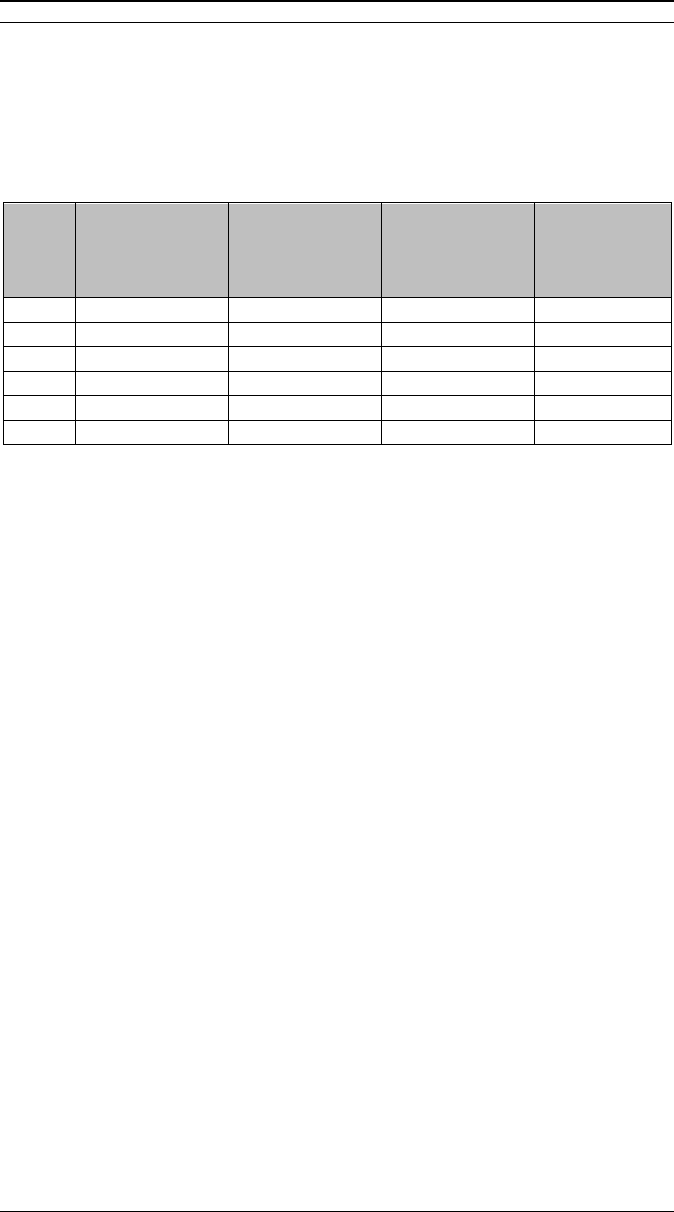

A. Reported and Expected Deaths from Aid in Dying Medications

150

In Oregon’s data from 2017 through 2018, physicians wrote 467

prescriptions for aid in dying medication, and within the two years, 311

people died from ingesting the prescribed medication.

151

United States

census data for July 2017 through July 2018 revealed that 36,052 people

died in Oregon that year,

152

suggesting that 0.86% of deaths in Oregon

could have resulted from aid in dying medication.

California’s 2017–2018 data showed that physicians wrote 1,029

prescriptions for aid in dying medication, and within that period, 711

people died from the medication.

153

Census data for July 2017 to July

2018 revealed that 280,674 people died in the state that year,

154

suggesting that 0.25% of deaths in California could have resulted from

aid in dying medication.

Washington’s 2017–2018 data shows that physicians wrote 479

prescriptions for aid in dying medication, and within the two years, 367

people died from the medication.

155

Census data for July 2017 to July

150

See infra App’x. at 874. Note the lack of data for two other continental states that

allow physician-assisted dying. Montana’s Supreme Court ruled that Montana’s laws

allow for physicians to provide medication to hasten patient death; thus, the state has

not created an aid in dying statute with a reporting requirement and has not made data

readily available. See Baxter v. State, 224 P.3d 1211, 1222 (Mont. 2009); see also

Montana, DEATH WITH DIGNITY, https://www.deathwithdignity.org/states/montana (last

visited Jan. 5, 2020). Vermont’s statute requires physicians to report writing

prescriptions and death by aid in dying medication, but the state is only required to

report every other year. See Report Concerning Patient Choice at End of Life, VT. DEP’T

HEALTH (Jan. 15, 2018), https://www.healthvermont.gov/systems/end-of-life-

decisions/patient-choice-and-control-end-life. The initial and most recent report

included years 2013–2017, so Vermont’s available data is not comparable to the other

states’ 2017–2018 data. See id.

151

Death with Dignity Act Annual Reports, OR. HEALTH AUTHORITY,

https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/providerpartnerresources/evaluationresearch/dea

thwithdignityact/pages/ar-index.aspx (Year 2018) (last visited Sept. 20, 2019).

152

2018 National State and Population Estimates: Table 5. Estimates of the

Components of Resident Population Change for the United States, Regions, States, and

Puerto Rico: July 1, 2017 to July 1, 2018, U.S. CENSUS BUREAU, https://www.census.gov/

newsroom/press-kits/2018/pop-estimates-national-state.html (last visited Sept. 20,

2019) [hereinafter 2018 National State and Population Estimates]. Note that available

census data to track vital life events are measured from July 2017 through July 2018,

while the states produce annual aid in dying reports on the calendar year. Id. This

means, for example, a death in Colorado in June 2017 would be reflected in Colorado’s

data, but not in the census for July 2017–July 2018.

153

End of Life Option Act 2018 Data Report, CAL. DEP’T PUB. HEALTH, at 3,

https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CHSI/Pages/End-of-Life-Option-Act-.aspx (last

visited Sept. 20, 2019). Note that the two most common prescriptions were for

sedatives and “a combination of a cardiotonic, opioid, and sedative.” Id. at 3.

154

See 2018 National State and Population Estimates, supra note 152.

155

2018 Death with Dignity Act Report, WASH. ST. DEP’T HEALTH, at 1,

https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 865

2018 revealed that 57,568 people died in the state that year,

156

suggesting that 0.25% of deaths in Washington could have resulted from

aid in dying medication.

In its first two years of implementing its act, Colorado collected

data showing that physicians wrote 197 prescriptions for aid in dying

medication and that between 2017 and 2018, 174 people died from

ingestion.

157

Census data for July 2017 to July 2018 revealed that 38,367

people died in the state that year,

158

suggesting that 0.45% of deaths in

Colorado could have resulted from aid in dying medication.

B. Data-Reporting Concerns and Predictions

The lack of a maximum time between requests contributes to a

data-reporting issue. Current reports do not measure the time a patient

spends in the initial stages of the aid in dying process.

159

A future

evaluation of the efficacy of the Act would benefit from understanding

how long patients take to complete a decision. The prescription-to-

administration-and-death timeline is only measured by the calendar

year in current reports.

160

The states’ data referenced above measures

when a patient received a prescription in one year but ingested the

medication in another year,

161

but the reports cannot show whether

these dates happen quickly between December and January of two

calendar years or if patients tend to hold medication for many months

or even a full year before self-administering. New Jersey’s future data,

if it only follows its current reporting requirements,

162

will also fail to

measure these points and track these issues.

2018.pdf (last visited Sept. 20, 2019); 2017 Death with Dignity Act Report, WASH. ST. DEP’T

HEALTH, at 1, https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-Death

WithDignityAct2017.pdf (last visited Sept. 20, 2019).

156

See 2018 National State and Population Estimates, supra note 152.

157

Colorado End-of-Life Options Act, Year Two 2018 Data Summary, with Updates to

2017 Data, COLO. DEP’T PUB. HEALTH & ENV’T, at 2, https://drive.google.com/file/d/

1FmoyCcL2gHopDO9rCJ2lGFEMUye8FQei/view (last visited Sept. 20, 2019). Some

individual state data, such as Colorado’s data, indicates the patient’s terminal illness. See

id. Looking at this available data and discussing the physical symptoms of different

illnesses might provide insight on the different capabilities of patients to self-

administer.

158

See 2018 National State and Population Estimates, supra note 152.

159

See sources cited supra notes 151–157.

160

See sources cited supra notes 151–157.

161

See sources cited supra notes 151–157.

162

The New Jersey statute includes the following reporting requirements:

(1) No later than 30 days after the dispensing of medication pursuant

to P.L.2019, c.59 (C.26:16-1 et al.), the physician or pharmacist who

dispensed the medication shall file a copy of the dispensing record

with the department, and shall otherwise facilitate the collection of

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

866 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

Despite these omissions of potentially useful data, this Comment

purports to make predictive calculations for New Jersey’s use of aid in

dying. These predictions are simply rough calculations to raise

potential concerns, address typical questions around aid in dying, and

encourage facilities and physicians to further prepare for the Act in New

Jersey. The average of the above states’ percentages of death from

ingesting prescribed medication is approximately 0.55% of state deaths.

The average lies closest to Colorado’s 0.45%, which reflects a

percentage of deaths in a state that has only had an aid in dying option

for a few years. By taking the 0.55% average and multiplying by the

number of Maine deaths from July 2017 to July 2018 (14,079 deaths),

163

we can predict 77 deaths in Maine from ingesting prescribed

medication. By multiplying the same 0.55% average by New Jersey’s

total deaths from July 2017 to July 2018 (76,370),

164

we can estimate

about 420 deaths within two years.

165

The average number of prescriptions within the past two years in

Oregon, California, Washington, and Colorado is 543 prescriptions. The

average of the confirmed deaths from ingesting prescribed medication

is 390.75 deaths. Comparing the 543 prescriptions to the 390.75 deaths,

there is an average proportion of 1.4 aid in dying prescriptions per

death from ingesting the medication. Applying this proportion to Maine

suggests 107.8 prescriptions within two years. Applying it to New

Jersey suggests 588 prescriptions within two years. These predictions

would be even higher than the values for the past two years in

Oregon,

166

a state that has had its act in place for decades.

such information as the director may require regarding compliance

with P.L.2019, c.59 (C.26:16-1 et al.).

(2) No later than 30 days after the date of the qualified terminally ill

patient’s death, the attending physician shall transmit to the

department such documentation of the patient’s death as the director

shall require.

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-13.

163

See 2018 National State and Population Estimates, supra note 152.

164

See id.

165

On July 31, 2020, approximately a year after enactment, New Jersey’s Department

of Health released its first annual report. Annual Report Chronicles Impact of New Jersey’s

Death with Dignity Law, N.J. DEP’T OF HEALTH (July 31, 2020) [hereinafter Annual Report],

https://www.nj.gov/health/news/2020/approved/20200731b.shtml. While only

twelve reported deaths, the state only released from between August 1, 2019 and

December 31, 2019. Id. The release offers no explanation for the lack of reports between

January 1, 2020 and July 30, 2020. Id.

166

See supra note 151 and accompanying text.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 867

These numbers do not, however, support any slippery slope

argument about people choosing to end their lives in New Jersey more

than in other states.

167

Furthermore, these elementary predictions are

simply meant to alert physicians and facilities that, insofar as New

Jersey is similar to other states and has a similar statute, patients may

use the Act similarly. At an estimated 588 prescriptions per

approximately two years, participating physicians across the state could

be writing approximately one prescription every other day. This

potential level of use supports the concerns in the discussion below

about considerations for changing residency and implementation to

avoid errors in physician discretion and use of the Act. These statutes

are as much about patient choice as they are about compliance and the

ability to report compliance with the definitions discussed above.

C. New Jersey Residency

While not explicitly stated in New Jersey’s act, it is important to

consider how New Jersey patients, physicians, and caretakers might lose

protection under the Act if a patient self-administers in another state.

168

This is an especially important consideration for people who qualify as

New Jersey residents because other states—New York and

Pennsylvania, namely—are in such close proximity but do not offer any

protections for medical aid in dying. Depending upon physical ability

and the type of illness, any transportation at the ultimate stage of an

illness may become impossible, but the self-administration and writing

requirements

169

in New Jersey do require some level of physical

strength that might make traveling with a terminal illness more

probable. While not the focus of this Comment, it is important to

mention that a patient’s ability to move and take a drug elsewhere

would create inaccuracies in how many people died in any given year in

a state from self-administering medication and could distort results in

reporting data as required by many of these statutes.

167

New Jersey just has more people, and more people could lead to a higher

number—but there is no need for concern. As a potential counter to any slippery slope

concerns about New Jersey’s trends: if New Jersey followed the Netherlands trend of

4.5% of deaths from euthanasia, it would be estimating about 3,437 deaths, a number

more than eight times greater than the 420 deaths predicted based off of United States

trends. In fact, in the first six months, New Jersey only recorded twelve deaths. See

Annual Report, supra note 165.

168

“If you take a dose prescribed under a death with dignity law outside the state

where you obtained it, you may lose the legal protections afforded by the law in

question. For example, your death may be ruled a suicide under another state’s law, with

resulting effects on your insurance policies.” Frequently Asked Questions, DEATH WITH

DIGNITY, https://www.deathwithdignity.org/faqs (last visited Sept. 18, 2019).

169

See discussion supra Section II.B.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

868 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

V. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NEW JERSEY

This Part will recommend best practices for New Jersey facilities,

including private practices or hospitals, under the current Act. Then, it

will offer some recommendations for amendments to the Act.

A. Implementation and Best Practices Under the Current Act

New Jersey facilities have to be careful not to unfairly limit a

patient’s ability to access the Act, but they can implement the internal

safeguards below without changing the procedures outlined in the Act.

Facilities have an interest in protecting their physicians and treating

their patients with respect, whether or not their physicians are willing

and able to aid in a patient’s death under the Act.

1. Provide Training for Self-administration

Similar to how Western Australia requires all physicians to learn

how to administer,

170

New Jersey facilities or medical and hospital

associations could provide training that teaches physicians how to teach

patients to self-administer properly. By enabling physicians to show

patients and families how to properly self-administer, New Jersey might

increase access to the Act for patients with certain physical disabilities

who may think they are incapable of using the Act. This training could

also show physicians how to teach caretakers to prepare drugs for a

patient’s self-administration. If New Jersey wants to follow other states

in requiring that the drugs be ingested rather than self-injected, the

training would have to differentiate between those two forms of

administration. This would help enforce that patients should be

ingesting medication, without explicitly changing the language of the

Act. Below, this Comment discusses the possibility of clarifying the Act

to include both forms of administration explicitly, therefore, expanding

the training possibilities. Lastly, providing physician training could

become a method for facilities and patients to determine which

physicians may be willing and able to participate in the aid in dying

process.

2. Documentation of Residency

Facilities should consider providing an internal system that allows

physicians to confirm a patient’s residency with a central residency

point-person. Similar to the tribunal appeal system required in Western

Australia, under the proposed system, a patient could ask for

reconsideration of a residency decision. Before the initial decision or at

170

See supra note 139 and accompanying text.

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

2021] COMMENT 869

the time of reconsideration, a physician and patient could refer to a

point-person in a facility’s legal department or a resource at a state-wide

medical or hospital association. While New Jersey’s act explicitly states

that the physician has discretion to accept another government

document as confirmation of residency,

171

there is nothing in the Act to

prevent a physician from consulting with other professionals about

whether the patient meets the residency requirement. The point-

person could have a list of other documents, such as a lease in the state,

or an understanding of a patient’s permanency or intent to return

(similar to Maine’s residency requirements)

172

to help a physician

consider a patient’s residency. The point-person could thoroughly

consider what, if any, properties, licenses, or leases a patient has in other

states that may determine whether a patient intends to stay in New

Jersey or return to another state or country.

A system for confirming residency would address some current

implementation issues that result from requiring medical professionals

to make determinations of residency. Such a system would protect

physicians from falsely identifying a patient as a resident through any of

the documentation. The system would also protect patients by making

sure that they are not prohibited from using the Act simply because one

physician did not determine residency under New Jersey’s requirement.

While there may be instances where a physician determines that a

person, such as an undocumented person, has enough “other

documentation” to show residency, but the point-person disagrees,

there could also be the inverse scenario where a physician does not find

enough documentation, but the point-person does and increases access

to the Act.

Facilities should additionally consider including residency

documentation within their data collection. Without including the

patient’s actual residency information, a facility could keep a record of

which type of documentation was provided to determine residency and

whether the facility found the patient to be a resident. If a facility,

through internal documents or state reports, finds that the unlisted

options available are being used frequently, this may be a warning that

non-New Jersey residents are crossing local state borders to access the

Act.

171

N.J. STAT. ANN. § 26:16-11.

172

ME. REV. STAT. ANN. tit. 418, § 2140(15) (2019).

NIGRO (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2021 10:54 AM

870 SETON HALL LAW REVIEW [Vol. 51:845

3. Limiting Time Between Requests

New Jersey only requires a minimum waiting period between

requests. Patients can wait more than fifteen days to make a second

request and can wait after two oral requests to make a written

request;

173

the law does not, however, prevent a physician from

continually clarifying that a patient is voluntarily requesting the

medication. Unlike other statutes, New Jersey physicians do not need to

prepare final request forms under the Act. Facilities could require

professionals participating in the Act to use similar forms to indicate the

physician’s own opinion at the time of prescription, even if an initial

determination of eligibility was made months or years earlier. This

Comment does not suggest that facilities require patients to make more

than the required number of requests, but rather that facilities supply a

tool for physicians to review the patient’s eligibility if the requests are

spread over time. New Jersey’s Department of Health website currently

provides a follow-up form, but it is only to confirm that the physician

followed the Act’s requirements.

174

A facility or physician’s practice

should have its own form, similar to the final attestation form in

California,

175

that notes a patient’s mental health and physical capacity

at the time the final request is made and confirms that the physician

informed the patient of the facility’s ingestion recommendation and

procedures.

4. Implementing Reporting Requirements

In teaching New Jersey health care professionals about the Act and

how to implement it effectively, it is important to recognize that, like

many other statutes, New Jersey’s act has reporting requirements.

176

Even though reporting is already required, implementation efforts for

the above definitions should continually emphasize the importance of