September 2013

IMF Policy Paper

IMF POLICY PAPER

REASSESSING THE ROLE AND MODALITIES OF FISCAL

POLICY IN ADVANCED ECONOMIES

IMF staff regularly produces papers proposing new IMF policies, exploring options for reform, or

reviewing existing IMF policies and operations. The following documents have been released and

are included in this package:

The Policy Paper on Reassessing the Role and Modalities of Fiscal Policy in Advanced

Economies prepared by IMF staff and completed on June 21, 2013 to brief the Executive

Board on July 24, 2013.

The Executive Board met in an informal session, and no decisions were taken at this meeting.

The publication policy for staff reports and other documents allows for the deletion of market-

sensitive information.

Copies of this report are available to the public from

International Monetary Fund Publication Services

P.O. Box 92780 Washington, D.C. 20090

Telephone: (202) 623-7430 Fax: (202) 623-7201

E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.imf.org

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D.C.

September 17, 2013

REASSESSING THE ROLE AND MODALITIES OF FISCAL

POLICY IN ADVANCED ECONOMIES

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This paper investigates how developments during and after the 2008–09 crisis have

changed economists’ and policymakers’ views on: (i) fiscal risks and fiscal sustainability;

(ii) the effectiveness of fiscal policy as a countercyclical tool; (iii) the appropriate design

of fiscal adjustment programs; and (iv) the role of fiscal institutions.

Advanced economies have experienced much larger shocks than was previously

thought possible and sovereign-bank feedback loops have amplified sovereign debt

crises. This has led to reassessing what constitutes “safe” sovereign debt levels for

advanced economies and has prompted a more risk-based approach to analyzing debt

sustainability. Precrisis views about the interaction between monetary and fiscal policy

have also been challenged by the surge in central bank purchases of government debt.

This has helped restore financial market functioning, but, to minimize the risk of fiscal

dominance, it is critical that central bank support is a complement to, not a substitute

for, fiscal adjustment.

The crisis has provided evidence that fiscal policy is an appropriate countercyclical

policy tool when monetary policy is constrained by the zero lower bound, the financial

sector is weak, or the output gap is particularly large. Nevertheless, a number of

reservations regarding the use of discretionary fiscal policy tools remain valid,

particularly when facing “normal” cyclical fluctuations.

The design of fiscal adjustment programs, and particularly the merit of frontloading, has

returned to the forefront of the policy debate. Given the nonlinear costs of excessive

frontloading or delay, countries that are not under market pressure can proceed with

fiscal adjustment at a moderate pace and within a medium-term adjustment plan to

enhance credibility. Frontloading is more justifiable in countries under market pressure,

though even these countries face “speed limits” that govern the desirable pace of

adjustment. The proper mix of expenditure and revenue measures is likely to vary,

depending on the initial ratio of government spending to GDP, and must take into

account equity considerations.

The crisis has revealed the challenges involved in establishing credible medium-term

budget frameworks and fiscal rules to underpin fiscal policy that are also sufficiently

flexible to respond to cyclical fluctuations. Moreover, shortcomings in fiscal reporting

point to the need to reassess the adequacy of fiscal transparency institutions.

June 21, 2013

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Approved By

Olivier Blanchard and

Carlo Cottarelli

Prepared by a staff team led by Bernardin Akitoby and comprising

Nathaniel Arnold, Mark De Broeck, Geremia Palomba, Jaejoon Woo,

Luc Eyraud, Andrea Schaechter, Anke Weber, Jason Harris, Richard

Hughes, Johann Seiwald, Sami Ylaoutinen, Asad Zaman (all FAD);

Daniel Leigh, Suman Basu (RES); Manal Fouad (ICD); S. Ali Abbas (EUR);

and Emine Hanedar (Dutch Ministry of Finance). External comments

were provided by Roberto Perotti. General guidance was provided by

Philip Gerson (FAD) and Jonathan Ostry (RES). Production assistance

was provided by Patricia Quiros, Juliana Peña, and Ted Twinting (FAD).

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATION ____________________________________________________________ 4

FISCAL RISKS, SOLVENCY, AND SUSTAINABILITY ______________________________________________ 4

A. Fiscal Risks, Fiscal Solvency, and “Safe” Levels of Debt __________________________________________ 5

B. Financial Market Discipline of Sovereigns and Multiple Equilibria _____________________________ 11

C. Central Bank Financing and Fiscal Dominance ________________________________________________ 13

D. Sovereign-Bank Links and Risks from Private Sector Balance Sheets _________________________ 13

FISCAL POLICY AS A COUNTERCYCLICAL TOOL ______________________________________________ 16

A. Fiscal Policy Effects ____________________________________________________________________________ 17

B. Fiscal Policy Implementation __________________________________________________________________ 21

THE DESIGN OF FISCAL ADJUSTMENT ________________________________________________________ 28

A. The Pace of Fiscal Adjustment _________________________________________________________________ 29

B. The Composition of Fiscal Adjustment ________________________________________________________ 33

BUDGETARY INSTITUTIONS, FISCAL TRANSPARENCY, AND FISCAL RULES ________________ 37

A. The Design of Medium-Term Budget Frameworks ____________________________________________ 37

B. The Transparency of Fiscal Accounts __________________________________________________________ 39

C. The Effectiveness and Design of Fiscal Rules __________________________________________________ 41

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FISCAL POLICY ____________________________________ 46

ISSUES FOR DISCUSSION _______________________________________________________________________ 49

References _______________________________________________________________________________________ 50

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

BOXES

1. Fiscal Space and Prudent Debt Levels: Issues to Consider _______________________________________ 9

2. Equity Considerations for Program Design in the Crisis _______________________________________ 36

FIGURES

1. Commercial Bank Assets for Selected Countries Before the Crisis _______________________________ 6

2. Average Structural Balance and Public Debt Ratios for Advanced Economies

and the Euro Area _______________________________________________________________________________ 6

3. Cumulative Change in Gross Debt to GDP Since the Start of Recessions ________________________ 7

4. G-20 Advanced Economies: Increase in General Government Debt, 2008–15 ___________________ 8

5. Advanced Economies: Fiscal Stimulus and Precrisis Net Debt Levels __________________________ 10

6. Sovereign Bond Yields for Select EMU Countries, 1992–2012 _________________________________ 12

7. Sovereign-Financial Linkages __________________________________________________________________ 14

8. Sovereign Bond Yields, Net Foreign Assets, and the Change in Non-financial

Private Sector Indebtedness from 2001–10 ___________________________________________________ 16

9. United States: Historical Multiplier for Total Government Spending __________________________ 20

10. Advanced Economies: Time Lag Between Lehman Failure and

Fiscal Stimulus Packages _____________________________________________________________________ 22

11. G-20 Advanced Economies: Contributions of Discretionary Stimulus and

Automatic Stabilizers to the Primary Deficit, 2009-10 ________________________________________ 26

12. Timeline of U.S. Fiscal Packages and Federal Funds Rate, 2008–18 __________________________ 27

13. Government Expenditures During Global Recessions and Recoveries ________________________ 28

14. Advanced Economies: Fiscal Adjustment and Market Conditions ____________________________ 32

15. Advanced Economies: Phasing of Fiscal Adjustment _________________________________________ 32

16. OECD Countries: Average Composition of Fiscal Adjustment, 1978-2008 ____________________ 34

17. Average Three-Year Ahead Forecast Error, 1998–2007 _______________________________________ 38

18. Sources of Unanticipated Increases in Public Debt Between 2007 and 2010 _________________ 39

19. EU Countries: Precrisis Fiscal Performance and National Fiscal Rules ________________________ 43

20. Number of Countries with Budget Balance Rules Accounting for the Cycle __________________ 44

21. National Fiscal Rules Index ___________________________________________________________________ 44

TABLE

1. Selected Fiscal Stimulus Measures Used by Advanced Economies ____________________________ 25

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATION

1. Before the 2008–09 crisis, the consensus view was that fiscal policy should play a

limited role as a stabilization tool.

1

Monetary policy was seen as a sufficient tool for short-term

macroeconomic stabilization. Numerous studies questioned the effectiveness of fiscal policy for

stabilization purposes, partly based on Ricardian considerations, and instead emphasized the long-

term goals of fiscal policy, including the provision of public goods and services, and long-term fiscal

sustainability. In addition, sovereign debt crises were seen primarily as a phenomenon of emerging

market and low-income countries, of limited practical relevance for advanced economies.

2

Before

the crisis, it was also believed that when risk premia and sovereign borrowing costs were high, “non-

Keynesian” confidence effects or supply-side improvements, such as lower labor costs, could offset

much of the negative direct effects of fiscal adjustment on economic activity.

2. Despite this precrisis consensus, almost all advanced economies deployed fiscal

stimulus at the start of the crisis. This renewed reliance on fiscal policy may have been driven in

part by the depth of the downturn, interest rates at the zero lower bound (ZLB) for some advanced

economies that limited the scope for traditional monetary policy, and a moribund credit channel.

New research points to large fiscal multipliers when economic conditions resemble those prevailing

in advanced economies in the post-crisis period. Against this background, debate continues on the

merits of frontloaded versus gradual (but steady) fiscal adjustment when financing permits. In

addition, the scale of the current fiscal problem has revived the debate on the importance of

institutions that underpin fiscal adjustment.

3. This paper provides an organizing framework to draw preliminary fiscal policy lessons

from the crisis. It addresses four main areas: (i) fiscal risks and fiscal and debt sustainability; (ii) the

effectiveness of fiscal policy as a countercyclical tool; (iii) the design of fiscal adjustment; and

(iv) fiscal transparency, fiscal rules, and budgetary institutions. The analysis will focus on advanced

economies, the country group most directly affected by the crisis.

FISCAL RISKS, SOLVENCY, AND SUSTAINABILITY

4. The crisis has exposed macro-fiscal vulnerabilities in advanced economies (AEs) that

were not fully recognized beforehand. It has revealed that fiscal risks and the buffers required to

protect against them are much larger than previously thought. For example, headline fiscal surpluses

can mask large structural deficits during asset price booms and contingent liabilities stemming from

large internationally-connected domestic banks can dwarf reported public debts. Thus, assessments

of fiscal sustainability—traditionally rooted in headline fiscal balances and debt ratios—are now

1

When the paper uses terms such as “we,” “our views”, or “the consensus view,” it is referring to common or

widespread views of economists and policymakers.

2

While some analysts did point to concerns about long-run sustainability in advanced economies, these were based

on the long-term demographic pressures, not doubts about short-term solvency.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

being reconsidered to take better account of the underlying (structural) fiscal position, the likelihood

of events that could threaten fiscal sustainability, and the speed with which markets’ perceptions of

sovereign risk can change.

5. The sovereign debt crisis in the euro area has shown that the precrisis belief that AEs

were not at risk of a fiscal crisis was misplaced. Among other things, the crisis exposed

shortcomings in the euro area institutional architecture, including those that prevented the provision

of timely and sufficient support to banks and sovereigns under duress (Ghosh, Ostry, and Qureshi,

2013). In light of central banks’ recent role in eliminating risks of bad equilibria, economists have

also questioned the precrisis consensus on avoiding central bank financing of the government. This

section will lay out the precrisis views on each of these topics and assess how the crisis and its

aftermath have caused our thinking to evolve.

A. Fiscal Risks, Fiscal Solvency, and “Safe” Levels of Debt

6. Before the crisis, we thought AEs were less exposed to fiscal risks. During the two

decades preceding the crisis—a period referred to as “The Great Moderation”—AEs exhibited much

less volatility in macroeconomic variables than did emerging markets (EMs) and low-income

countries. Also, systemic financial crises in AEs were thought to be relatively rare and the related

contingent liabilities, if they were to materialize, were thought to pose a limited risk to these

countries (Laeven and Valencia, 2012). Moreover, little attention was paid to possible adverse

feedback loops between bank risk and sovereign risk, despite the presence of large financial sectors

in many AEs (Figure 1).

7. The probability of a full-blown fiscal crisis in AEs was generally considered remote,

despite the looming fiscal impact of aging-related spending. Before 2007 there appeared to be

little concern about the short-run fiscal solvency of most AEs, in spite of nontrivial fiscal deficits,

particularly in the euro area, and relatively high debt-to-GDP ratios (Figure 2).

3

This reflected a

number of factors. First, the view prevailed that when financial markets are sufficiently developed

and deep, they can easily absorb temporary surges in public debt. Second, advanced economies

were perceived as having fiscal institutions that would ensure that debt surges would lead to later

fiscal corrections. Third, in the euro area, membership in the area was seen as sufficient to avoid a

surge in interest rates since government bonds issued by different countries could be regarded as

(nearly) perfect substitutes. However, there was significant concern about the impact of population

aging on fiscal solvency in many AEs over the long run (Heller and Hauner, 2005; Hauner, Leigh, and

Skaarup, 2007).

3

The structural deficits depicted in Figure 2 are current estimates. As noted, before the crisis structural deficits

appeared to be smaller.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 1. Commercial Bank Assets for Selected Countries Before the Crisis

(Percent of GDP)

Sources: IMF Global Financial Stability Report, various issues.

Figure 2. Average Structural Balance and Public Debt Ratios for Advanced Economies and the

Euro Area

(Percent of GDP)

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO), Fiscal Monitor, and Historical Public Debt Database.

8. The precrisis build up of fiscal and macro-financial imbalances in AEs posed much

larger risks than previously thought. Partly owing to the difficultly of diagnosing asset bubbles

until they have burst, such bubbles emerged undetected. In some countries, such as Ireland and

Spain, headline fiscal surpluses generated by housing and credit booms masked unsustainable

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

DEU GBR ESP IRL GRC IT

A

FRA USA

2003 2007

0

20

40

60

80

100

0

20

40

60

80

100

All AEs

Euro Area

Gross Public Debt Ratio

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

All AEs

Euro Area

Structural Fiscal Balance

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

structural fiscal positions that were revealed when the crisis struck.

4

The fiscal risks created by large

(relative to GDP), growing, and interconnected financial sectors were also underappreciated, partly

because of confidence in financial markets’ capacity to self-regulate (Greenspan, 2010) and the

opacity of cross-border exposures.

5

9. During the crisis, debt increased much more than was thought possible, raising doubts

about what level of debt could be regarded as “safe.” Since 2008, macroeconomic and fiscal

shocks have been much larger than previously anticipated, which has caused debt-to-GDP ratios to

rise much faster than in prior downturns (Figure 3). On average, most of the surge in debt-to-GDP

ratios has been due to a shortfall in revenues as a byproduct of sluggish growth in the aftermath of

the financial crisis, rather than to direct fiscal costs from bailing out banks (Figure 4).

6

However, in

Ireland and Iceland, bank rescues drove an (unexpected) increase in the debt ratio of 41 and 43

percentage points of GDP, respectively. These two cases illustrate that even levels of debt well below

what was considered prudent before the crisis may not be “safe” in the face of large potential

contingent liabilities.

Figure 3. Cumulative Change in Gross Debt to GDP Since the Start of Recessions

(Percent of GDP)

Sources: Kinda, Poplawski-Ribeiro, and Woo (2013), and IMF staff estimates and projections.

Notes: Solid line corresponds to 2008—12, and dashed line to 2013—17.

4

The structural balance is generally defined as cyclically adjusted balance corrected for “one-off” items. Newer

measures of the structural balance also make adjustments for factors beyond the business cycle, such as asset prices

cycles (e.g., housing, stock markets). The cyclically adjusted balance is the difference between the overall balance and

the automatic response of fiscal variables to changes in output (i.e. automatic stabilizers).

5

A prime example of cross-border exposures is the exposure of German banks, especially the publicly-owned

Landesbanken, to complex asset-backed securities (e.g., backed by sub-prime mortgages) from the United States.

6

Note, however, that part of the revenue loss is not regarded as cyclical, not only because revenues were inflated by

asset price bubbles but also because part of the output loss during the crisis is regarded as permanent.

-15

-5

5

15

25

35

t+1

t+3

t+5

t+7

t+9

Past recessions, 25th

–

75th percentiles

Past recessions, median

Current crisis

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

t t+1 t+2 t+3 t+4 t+5 t+6 t+7 t+8 t+9

Years

Advanced

Economies

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 4. G-20 Advanced Economies: Increase in General Government Debt, 2008–15

(Percentage points of GDP)

(April 2013 projected total increase: 37.1 percentage points of GDP)

Sources: IMF staff estimates and projections based on the Fiscal Monitor (see IMF, 2011a).

Note: Weighted average based on 2009 purchasing power parity-GDP.

10. As a result, there is a need for a more holistic approach to measuring public debt and

determining “safe’’ levels of debt. The official debt ratio fails to reflect contingent liabilities, which

are often underestimated until they materialize (Irwin, 2012). This argues for a much lower “safe”

debt level than was thought necessary before the crisis (Ostry and others, 2010; Blanchard, Mauro,

and Dell’Ariccia, 2013). On the other hand, the crisis has also shown that for some AEs considered

safe havens (Japan and the United States, for example), markets can tolerate much higher debt

ratios than previously thought, at least for a time. Since sentiment can shift quickly, a cautious

government may rationally err on the side of having a low debt ratio in order to avoid the risk of

punishment by the market (Mendoza and Ostry, 2008; Ostry and others, 2010). These issues have

prompted new research on assessing fiscal space in AEs (Box 1).

Revenue loss

21.7

Fiscal stimulus

6.4

Financial

sector support

1.9

Net lending

and other

stock-flow

adjustments

2.8

Interest rate-

growth

dynamics

4.4

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Box 1. Fiscal Space and Prudent Debt Levels: Issues to Consider

The literature has recently proposed various definitions of fiscal space. Aizenman and Jinjarik

(2010) use the debt-to-revenue ratio as a simple measure of fiscal space (with a lower ratio meaning

more space). Bi and Leeper (2012) propose the notion of country-specific fiscal limits, defined as “the

point at which for economic or political reasons taxes and spending can no longer adjust to stabilize

debt,” at which point, fiscal space runs out (see also Bi, 2012). Focusing on the debt level, recent IMF

research has developed a new and more precise definition of fiscal space, defining it as the distance

between the current (or projected) debt ratio and the debt limit, the point above which the sovereign

loses market access (Ostry and others, 2010; Ghosh and others, 2013). The debt limit is determined by

the maximum primary balance (PB) that can be sustained both economically and politically (i.e. the

fiscal limit) and the interest rate-growth differential (r-g), which is the difference between the real

interest rate on public debt and the real GDP growth rate (IMF, 2011b). While the assessment of r-g is

essentially forward looking, a country’s historical experience can be informative. Comparator countries’

experiences could also be used, where appropriate.

There are several approaches to gauging the level of the maximum sustainable primary balance.

One may look at a country’s history, institutions (and how they might change), at periods of

extraordinary fiscal effort, or regional peers (Abiad and Ostry, 2005). Using a country’s best historical

fiscal performance as a proxy for future fiscal performance helps inform the assessment of what

constitutes the maximum fiscal effort. As Rogoff, Reinhart, and Savastano (2003) argue: “history

matters: a country’s record at meeting its debt obligations and managing its macroeconomy in the past

is relevant to forecasting its ability to sustain moderate to high levels of indebtedness for many years

into the future.” However, this does not take into account that relatively low primary surpluses in the

past may simply reflect a period in which there was not an urgent need for fiscal adjustment. Thus,

historical experience does not necessarily imply that a country cannot achieve higher surpluses when it

has a high (or unsustainable) debt level and wants to put the debt ratio firmly on a downward

trajectory.

A country’s desired degree of fiscal space should account for fiscal risks. Assessments of country-

specific fiscal risks can help inform the decision on how much fiscal space to maintain. For example,

stochastic projection methods that model correlated shocks, such as the “fan chart” approach

developed by Celasun, Debrun, and Ostry (2007), can help estimate the size of the risks posed by

macroeconomic shocks. Such assessments should also take into account the country’s policy flexibility

(e.g., monetary sovereignty), long-term fiscal pressures (e.g., aging-related spending), risk management

(e.g., fiscal institutions that conduct regular risk assessments) and mitigation measures (e.g., higher

capital requirements for banks if the banking sector is large relative to the economy), as well as the

degree of cross-country risk sharing available to offset different shocks (e.g., a banking union in the

euro area). In sum, this means there is not a one-size-fits-all “safe” level of debt.

11. Countries may also want to maintain lower debt levels to create fiscal space for

countercyclical fiscal policy. Christiansen and Perez Ruiz (2013) find that over the past four

decades, discretionary countercyclical fiscal responses have been provided mainly by governments

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

with lower debt levels. Consistent with this finding, in the recent crisis the discretionary

countercyclical fiscal policy response of AEs appears to be negatively associated with their initial

debt levels (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Advanced Economies: Fiscal Stimulus and Precrisis Net Debt Levels

(Percent of 2008 GDP and percent of 2007 GDP, respectively)

Sources: IMF staff estimates based on WEO and Fiscal Monitor data (IMF, 2010a).

Notes: Sample includes Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, New Zealand,

Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The fiscal stimulus measure is from the Fiscal Monitor database. Several

countries for which data are available that have a net debt ratio less than -10 percent of GDP (Norway, Finland, and Sweden) are

excluded for presentational purposes. Including these outliers would strengthen the relation between the size of stimulus measures

and initial net debt levels.

12. In light of the above lessons, debt sustainability analysis should take a more risk-based

approach than in the past.

7

Most importantly, sensitivity analyses need to capture country-specific

fiscal risks and vulnerabilities, especially risks from the financial sector.

8

The macro-fiscal shock

scenarios should also reflect interactions among key variables, and capture the impact of correlated

shocks (for instance through a fan chart). To help prevent contingent liabilities from public

enterprises and other state-related entities from catching policymakers off-guard, analyses should

be conducted using the broadest possible definition of the public sector. For example, in the United

States, potential contingent liabilities stemming from the debt of government-related enterprises is

estimated to exceed 50 percent of GDP (IMF, 2013a).

7

For further details see IMF Policy Papers “Modernizing the Framework for Fiscal Policy and Debt Sustainability

Analysis for Market-Access Countries” (IMF, 2011b) and “Staff Guidance Note for Public Debt Sustainability Analysis

for Market-Access Countries” (IMF, 2013b).

8

This includes vulnerabilities stemming from not having monetary sovereignty, as in a currency union.

AUS

CAN

DNK

FRA

DEU

ISR

ITA

JPN

KOR

NLD

NZL

PRT

ESP

GBR

USA

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

-20 0 20 40 60 80 100

2009–10 Discretionary Stimulus

(in percent of 2008 GDP)

Net Debt in 2007 (percent of GDP)

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

B. Financial Market Discipline of Sovereigns and Multiple Equilibria

13. The ability of financial markets to “discipline” profligate governments was a subject of

active debate before the crisis.

9

Financial markets discipline government finances primarily

through the response of the sovereign debt risk premium to higher fiscal deficits and public debt

levels, with markets demanding higher interest rates to compensate for a perceived rise in default

risk and, in extremis, by denying access to financing altogether (Akitoby, 2006; Akitoby and

Stratmann, 2008). In the euro area, some thought that the Maastricht Treaty’s “no bailout” clause

would reinforce financial market discipline. However, skepticism about the effectiveness of the

market discipline mechanism was also present in the early stages of the European Monetary Union

(EMU), and was indeed the main rationale for the introduction of fiscal rules in the area. The 1989

Delors Report noted that “[t]he constraints imposed by market forces might either be too slow and

weak or too sudden and disruptive.”

14. It is still an open question as to why market discipline may have been ineffective in the

euro area.

10

The focus on headline fiscal positions, temporarily inflated in some countries by asset

prices and credit booms, distracted attention from the widening of underlying fiscal deficits and the

buildup of private sector imbalances (e.g., in Ireland and Spain). Investors may also have rationally

believed that the “no bailout” clause lacked credibility. This could reflect the presumption that, for

either political or economic reasons, an EMU member facing sovereign debt distress would be

supported by other member states or the ECB, which treated all members’ public debt as risk free

(Jahjah, 2001; Buiter and Siebert, 2006; Gros, 2013).

11

While this belief was partly confirmed by the

euro area’s response to the crisis, the expected bailouts did not materialize smoothly. This may have

caused markets to revise their assumption that the “no bailout clause” lacked credibility. In fact,

spreads for the crisis-hit countries widened to levels that greatly exceeded what deteriorating

fundamentals alone could explain (Poghasyan, 2012; IMF, 2012a; De Grauwe and Ji, 2013), as market

attention focused on the difficulties of adjustment inherent in currency union membership (Ghosh,

Ostry, and Qureshi, 2013) and concerns about currency convertibility risk re-emerged (i.e. that a

country would exit the euro area).

12

15. The sovereign debt crisis in Europe has brought to light the risk of multiple equilibria.

Multiple equilibria risks can emerge if investors become concerned about the possibility of

9

See, for instance, Alesina and others (1992) for some earlier evidence supporting the market discipline hypothesis.

10

Although part of the precrisis convergence to very low interest rate spreads among member states reflected the

convergence of their inflation rates and removal of currency devaluation risk with the adoption of the euro, the wide

variance in the underlying fiscal positions of the member states may have justified wider spreads. For instance, in

2005, interest rate differentials on government bonds were only about 30 basis points, with budget balances ranging

from a 2 percent of GDP surplus to a 5 percent deficit and debt ratios between 7 percent and 108 percent of GDP.

11

Despite how it was presented, the “no bailout clause” did not technically prevent some sort of assistance to

distressed members, which may also account for some of the skepticism.

12

See the July 26

th

, 2012, speech by Mario Draghi, the President of the ECB at the Global Investment Conference in

London. Available online at: http://www.ecb.int/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120726.en.html.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

sovereign default and begin to demand higher interest rates. This makes it more costly for a

sovereign to service its debt, thereby increasing the risk of default and potentially making investor

concerns self fulfilling. Multiple equilibria can emerge even at low levels of debt, but are more likely

at high debt levels, since a smaller move in interest rates can shift the sovereign from solvency to

insolvency (Blanchard, Mauro, and Dell’Ariccia, 2013).

Figure 6. Sovereign Bond Yields for Select EMU Countries, 1992–2012

(Percent; monthly data)

Sources: National Data, Bloomberg, and European Central Bank.

16. In principle, a central bank can prevent a bad equilibrium by committing to provide

liquidity to the sovereign bond market to facilitate its monetary policy objectives. Events

during the crisis suggest that currency union members, in particular, are prone to multiple equilibria

risks. The market’s differentiated treatment of the United Kingdom and Spain—two countries with

similar fiscal and debt dynamics—seems to suggest that the Bank of England was able to prevent

the risk of a liquidity crisis in the UK sovereign debt market (De Grauwe, 2011), although the long

average maturity of UK sovereign debt also reduced rollover risks. The commitment of the ECB to

intervene, if necessary and conditional upon fiscal adjustment, appears to have reduced the risk of

“bad equilibria” in the euro area (Abbas and others, 2013). However, in practice intervention could

require large purchases and there are likely to be limits on how much a central bank can do. It can

be difficult to distinguish between illiquidity and insolvency situations, so the central bank may

worry it is taking too much credit risk (Blanchard, Mauro, and Dell’Ariccia, 2013).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

France Germany

Italy Spain

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

C. Central Bank Financing and Fiscal Dominance

17. Central bank financing of the budget could undermine its independence and its

control of inflation.

A key lesson from the “unpleasant monetarist arithmetic” of Sargent and

Wallace (1981) is that lax fiscal policy can put pressure on the monetary authorities to monetize

public debt. If fiscal imbalances are sufficiently large over a long period, it creates a risk that

monetary policy could eventually become subservient to fiscal considerations (so-called “fiscal

dominance”) and the central bank’s inflation objective would be seriously compromised. To avoid

this state of affairs, prior to the crisis monetary policies in AEs were typically focused on price

stability as their main objective and central banks were given operational independence, including

prohibitions on directly funding government deficits (Mishkin, 2000).

18. Central banks’ actions since 2008 have challenged our precrisis views about fiscal and

monetary interactions. The surge in central bank purchases of government debt has been

spectacular in some countries. For instance, the U.S. Federal Reserve has purchased large quantities

of U.S. government debt as part of its unconventional monetary policy (UMP) measures, more than

doubling its holdings between 2007 and 2011. Similarly, by the end of 2012, the Bank of England

increased its holdings of U.K. government debt from almost nothing to more than a quarter of the

outstanding stock.

13

So far, the massive expansion of some central banks’ balance sheets—aimed at

repairing the broken monetary policy transmission mechanism—has not undermined the credibility

of fiat money, as inflation expectations remain well anchored in the context of a liquidity trap.

14

19. Central bank purchases of government debt have turned out to be useful to allow for

a more gradual fiscal adjustment. Accommodative monetary policy can support fiscal adjustment

in that it reduces the cyclical impact of fiscal adjustment and the risk that fiscal tightening is

counterproductive (leading potentially to a rise in interest rates; Cottarelli and Jaramillo, 2012).

However, given high debt levels in most AEs, fiscal adjustment is necessary to avoid the risk of fiscal

dominance down the road. The risk of governments pressuring central banks to help limit borrowing

costs may arise if public debt levels remain high when it is time to normalize monetary policy

(Blanchard, Mauro, and Dell’Ariccia, 2013).

D. Sovereign-Bank Links and Risks from Private Sector Balance Sheets

20. Domestic bank holdings of public debt were not thought to pose a risk to the financial

system in AEs. If anything, holding sizable amounts of safe and liquid assets, like government debt,

13

Prohibitions on “monetary financing” of the government did not include the purchases of government bonds from

secondary markets, since these are often used to conduct open market operations in some countries. Thus, the

increase in purchases of government bonds by central banks has not violated existing legislation.

14

See IMF (2013d) for further discussion of UMP measures. Also, forthcoming work by IMF staff will examine fiscal

and monetary policy interactions, the quasi-fiscal aspects of UMP, and implications for Fund policy advice on central

bank purchases of government debt, as well as broader issues related to policy coordination between central banks

and governments, including in the case of a deep crisis.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

was thought to make banks less risky. This view was reflected in the regulatory capital rules that

allowed banks to assign a zero-risk weighting to holdings of their own government’s debt.

21. We have seen that a sovereign-bank feedback loop can emerge and amplify a

sovereign debt crisis. A sovereign-bank feedback loop can initially stem from either a rise in

sovereign yields diminishing the value of public debt held by domestic banks, raising concerns

about banks’ solvency when they hold large quantities of public debt, or from systemic banking

sector problems, with the potential fiscal costs raising concerns about fiscal solvency (Adler, 2012).

In such situations, a feedback loop emerges that is often fueled by increasing uncertainty regarding

the solvency of both the government and the banks, leading investors to demand higher default risk

premia and creating self-fulfilling crisis dynamics, as seen in the euro area crisis countries (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Sovereign-Financial Linkages

Sources: Bloomberg L.P.; Dealogic; national authorities; Arslanalp and Tsuda (2012); and IMF staff estimates.

1

Outstanding guaranteed bonds corresponding to bonds issued by private and public banks and financial institutions and carrying

state guarantees. Short-term debt is not included.

22. Decisive actions to reduce uncertainty and the risk of multiple equilibria are critical to

severing the sovereign-bank feedback. Severing sovereign bank links in the short run requires

short circuiting the emergence of self-fulfilling crisis dynamics. This calls for: (i) central bank

provision of sufficient liquidity to the financial sector and the sovereign bond market to ensure a

liquidity problem does not become a solvency problem; (ii) transparent and credible stress tests and,

if needed, plans to recapitalize or restructure weak banks at minimal fiscal cost; and (iii) formulating

and announcing a credible medium-term fiscal adjustment plan to reassure investors concerned

about fiscal solvency. As in the case of monetary financing of the deficit, the provision of large

AUS

AUT

BEL

DNK

FRA

DEU

IRL

ITA

NLD

NZL

PRT

KOR

ESP

SWE

GBR

USA

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

-4-202468

Change in 10-year sovereign bond

yields, 2008–12 (percent)

Change in government guarantees,

1

2008–12

(percent of GDP)

AUS

AUT

BEL

DNK

FRA

DEU

IRL

ITA

NLD

NZL

PRT

KOR

ESP

SWE

GBR

USA

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

0 10203040

Change in 10-year sovereign bond

yields, 2008–12 (percent)

Public debt held by domestic banks, 2011

(percent of GDP)

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

(potentially unlimited) amounts of liquidity to banks cannot be a substitute for addressing the

underlying problems.

15

23. For the euro area, a cross-country risk-sharing mechanism is needed to help break

national sovereign-financial linkages.

16

Given the size of national banking systems, banking sector

problems can easily overwhelm the fiscal capacity of a single member state. To prevent this, a

common backstop for dealing with distressed banks is needed. Recent policy announcements —

including the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and the political agreement to allow

bank capitalization directly through the European Stability Mechanism (ESM)—have provided some

financial respite. However, so far, other efforts to develop more robust risk-sharing mechanisms

have faced significant political economy hurdles. For example, proposals for “Eurobonds,” for which

EMU members would share joint liability, have not gained traction.

24. Macro-financial imbalances stemming from private non-financial sector balance sheets

can also pose risks to the sovereign. During the European sovereign debt crisis, a striking

correlation has emerged between the rise in private sector indebtedness (indicated by the area of

the bubble), the external liabilities of a country (as measured by the net foreign assets (NFA)

positions) and sovereign yields (Figure 8). This may be indicative that markets see a large increase in

private sector leverage as a risk factor for the sovereign, whether indirectly through lower growth if

deleveraging is drawn out or directly if the government is pressured to help bailout important firms

or industries. Such private sector indebtedness can also create additional indirect pressures on the

sovereign through the financial sector, as loan defaults rise. If the increase in private sector

indebtedness is externally financed, this may also compound a country’s vulnerability to a “sudden

stop” of capital flows because foreign creditors are more sensitive to changes in perceived risks

(IMF, 2012b). In sum, private sector balance sheets should not be ignored when assessing fiscal risks

and sustainability.

15

Although beyond the scope of this paper, the first response to large bank systems requires more fundamental

financial sector and regulatory reforms (IMF, 2013c; Global Financial Stability Report, various issues).

16

See IMF (2012c) for a further discussion of issues related to creating an EMU banking union.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 8. Sovereign Bond Yields, Net Foreign Assets, and the Change in Non-financial Private

Sector Indebtedness from 2001–10

(In percent and percent of 2010 GDP, respectively)

Sources: IMF International Financial Statistics, OECD.

Notes: The area of the bubbles represent the change in the non-financial private sector debt-to-GDP ratio between 2001 and 2010.

The color of the bubble indicates whether the change is positive or negative, with blue indicating an increase and white indicating a

decrease

FISCAL POLICY AS A COUNTERCYCLICAL TOOL

25. The prevailing consensus before the crisis was that discretionary fiscal policy had a

limited role to play in fighting recessions. The focus of fiscal policy in advanced economies was

often on the achievement of medium- to long-run goals such as raising national saving, external

rebalancing, and maintaining long-run fiscal and debt sustainability given looming demographic

spending pressures. For the management of business cycle fluctuations, monetary policy was seen

as the central macroeconomic policy tool. Fiscal contraction was sometimes recommended during

periods of economic overheating as a means of supporting monetary policy, for example to take

pressure off the exchange rate in the face of persistent capital inflows. However, during downturns,

it was deemed that there was little reason to use another instrument beyond monetary policy.

FRA

DEU

GRC

IRL

ITA

JPN

NLD

PRT

ESP

GBR

USA

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

-150 -100 -50 0 50 100

10-year Sovereign Bond Yields, 2011

(percent)

Net Foreign Assets, 2010

(percent of GDP)

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

Automatic stabilizers could be left to operate in economies that did not face financing constraints,

but there was little call for a more activist approach to fiscal policy.

17

26. There were many reasons for this consensus. First, there was widespread skepticism about

whether discretionary fiscal policy would have any meaningful impact on economic activity, while it

was generally accepted that monetary policy would do so. Second, lags in the design and the

implementation of fiscal policy, together with the short length of recessions, implied that even if

fiscal measures did affect output, their impact would likely come too late to be of much help. By

contrast, monetary policy could react more nimbly to economic developments, particularly when

conducted by a central bank with operational independence. Third, due to political constraints, fiscal

expansions in particular were seen as being easier to initiate during economic downturns than to

reverse during economic expansions, implying a ratcheting up of government spending and debt

over time.

A. Fiscal Policy Effects

27. For much of the two decades preceding the crisis, there was skepticism, both in

academia and among policymakers, regarding the macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy. The

skepticism, though not universal, reflected the possibility of a private sector offset to fiscal stimulus

and a lack of consensus in the empirical literature regarding the sign, let alone the magnitude, of

fiscal multipliers––the change in output resulting from a discretionary change in a government

spending or taxes.

18

Part of the literature even found evidence of negative multipliers. For example,

in seminal contributions, Giavazzi and Pagano (1990, 1996) showed that a number of fiscal

adjustments were correlated with expansions in private demand in the short term, providing

evidence of “expansionary fiscal contractions.”

28. The resurgence of countercyclical fiscal policy at the start of the crisis coincided with

new research on its macroeconomic effects. Some of this research, typically based on data

covering the precrisis period, concludes that fiscal multipliers have been low in advanced

economies, around 0.5 or less (Alesina and Ardagna, 2010; IMF, 2010b; Barro and Redlick, 2011, for

example). Other studies, also based on data covering normal times, find evidence of larger

multipliers, well above 1 (Romer and Romer, 2010, for example). However, in view of their reliance

on data covering the precrisis period, these studies are unlikely to fully reflect the peculiarities of the

current economic environment.

17

It is worth acknowledging that the rejection of discretionary fiscal policy as a countercyclical tool was not universal,

and was perhaps stronger in academia than among policymakers. Discretionary fiscal stimulus measures were

sometimes deployed in the face of severe shocks––for example, during the Japanese crisis of the early 1990s.

18

This uncertainty reflected various factors, including the difficulties involved in identifying the causal effects of fiscal

policy on economic activity due to two-way causality; different types of taxes and government spending; the

temporary or permanent nature of the measures; the initial state of the fiscal accounts; and different responses of

monetary policy.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

29. While debate continues, the evidence seems stronger than before the crisis that fiscal

policy can, under today’s special circumstances, have powerful effects on the economy in the

short run. In particular, there is even stronger evidence than before that fiscal multipliers are larger

when monetary policy is constrained by the zero lower bound (ZLB) on nominal interest rates, the

financial sector is weak, or the economy is in a slump. A number of studies have also questioned the

earlier evidence of negative fiscal multipliers associated with expansionary fiscal contractions.

Beyond this general conclusion, however, many open questions remain—in particular, on the

differential effects, if any, of changes in government spending and taxes, or the dependence of the

multiplier on the initial state of the fiscal accounts.

Fiscal multipliers: at the zero lower bound

30. During the crisis, central banks in most advanced economies quickly cut their policy

rates to close to zero. By most estimates, central banks would if possible have decreased policy

rates well below zero in the absence of the zero nominal interest floor constraint. For example,

Rudebusch (2009) estimates that, in the United States, based on the typical response of the Federal

Reserve to economic conditions before 2008, the federal funds rate would have declined to -5

percent in 2009. After economies hit the ZLB, central banks moved to using various unconventional

monetary policies. IMF (2013d) concludes that, while these policies generally reduced tail risks,

evidence regarding the policies’ macroeconomic effects is less clear cut. Similarly, Chung and others

(2012) conclude that “the Federal Reserve’s asset purchases, while materially improving

macroeconomic conditions, did not prevent the ZLB constraint from having first-order adverse

effects on real activity and inflation.”

31. A number of studies suggest that the ZLB constraint increases the size of fiscal

multipliers. Coenen and others (2012) quantify the effect of the ZLB on fiscal multipliers based on

seven macroeconomic models developed at six policy institutions.

19

In all seven models, fiscal

multipliers associated with various fiscal instruments rise substantially at the ZLB.

20

Based on data for

27 economies during the 1930s—a period during which interest rates were at or near the ZLB—

Almunia and others (2010) conclude that fiscal multipliers were about 1.6. For the current crisis,

Blanchard and Leigh (2013) argue that fiscal multipliers have been above 1 in economies at the ZLB,

at least in the early years of the crisis, based on the relation they find between growth forecast

errors and fiscal consolidation forecasts for these economies. Additional evidence that fiscal

19

The seven models employed by the study are the Bank of Canada Global Economy Model (BoC-GEM), the FRB-US

and SIGMA models of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the New Area-Wide Mode (NAWM) of

the European Central Bank, the QUEST model of the European Commission, the Global Integrated Monetary and

Fiscal Model (GIMF) of the IMF, and the OECD Fiscal Model.

20

See also, Christiano, Eichenbaum, and Rebelo (2011). In these studies, the ZLB amplifies the effects of fiscal policy

because policy interest rates do not respond to changes in fiscal policy in an offsetting manner. For example, at the

ZLB, central banks cannot cut policy interest rates to offset the negative short-term effects of a fiscal consolidation

on economic activity. By the same token, as long as the unconstrained policy rate is negative, the policy interest rate

does not rise during a fiscal expansion, and monetary policy thus accommodates the expansionary effects of fiscal

stimulus.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

multipliers can be large in settings where monetary policy is constrained come from studies based

on regional data from a particular country.

21

32. A related implication of the ZLB constraint on monetary policy is that fiscal policy

changes abroad are likely to have larger effects on the domestic economy. This is relevant for

settings where fiscal stimulus or consolidation occurs simultaneously in many economies (also see

the next section on the design of fiscal adjustment). Fiscal consolidation abroad reduces domestic

growth by reducing export demand. When the ZLB constrains the ability of the domestic central

bank to cut interest rates in an offsetting manner, the negative effect on the domestic economy is

likely to be larger (see IMF, 2010b, for an example). It is worth clarifying that the effect of fiscal

consolidation abroad comes in addition to the effect of any domestic fiscal consolidation. Since the

multiplier is larger at the ZLB—for any exogenous shock to aggregate demand—the final

contraction in output in response to the combined shock is likely to be larger when monetary policy

is constrained.

Fiscal multipliers: when the financial sector is weak

33. A key feature of the crisis has been the reduced availability of credit to households

and firms. Numerous advanced economies have experienced a systemic banking crisis (Laeven and

Valencia, 2012), with an associated reduction in the supply of loanable funds. More limited access to

credit implies that consumption and investment depend more strongly on current than on future

income. Therefore, fiscal policy changes, by affecting current income, have larger multipliers in

economies characterized by tighter credit constraints. To the extent that households and firms

become more credit constrained during financial crises, model simulations predict that fiscal

multipliers are likely to be larger during such episodes.

22

In line with this logic, Corsetti, Meier, and

Müller (2012) find that during actual historical episodes of financial crises, the responses of output

and consumption to public spending are substantially higher than during normal times, and are

consistent with fiscal multipliers as large as 2.

21

See, for example, Chodorow-Reich and others (2011) and Nakamura and Steinsson (2011) based on U.S. regional

data, and Acconcia, Corsetti, and Simonelli (2013) based on regional data from Italy. An important caveat applies to

studies that estimate fiscal multipliers based on subnational data. Taxpayers outside the region receiving central-

government funds may anticipate higher taxes in the future and reduce their spending accordingly through a

negative wealth effect. Since this negative wealth effect is limited at the regional level, the multiplier estimated at the

regional level would overstate the overall (national) output effect. At the same time, spending in one region could

increase demand in other regions, and such positive spillovers could imply that multipliers estimated at the regional

level would understate the overall output effect.

22

See Perotti (1999) and Fernandez-Villaverde (2010), for example. In related work, Eggertsson and Krugman (2012)

highlight the role of a private debt overhang in amplifying fiscal multipliers based on a New Keynesian theoretical

model. In their model, the debt limit of “impatient” households (who borrow from “patient” households) is suddenly

reduced. This makes these households’ spending more dependent on current income and, as a result, fiscal

multipliers rise well above 1.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Fiscal multipliers: in slumps

34. Earlier research often assumed that the impact of fiscal policy was similar across

different states of the economy, but a number of recent empirical studies suggest that fiscal

multipliers may be larger during periods of slack. Importantly, since these studies’ results are

based on precrisis data, their findings of larger multipliers in slumps reflect mechanisms distinct

from the ZLB and financial sector weaknesses discussed above. Instead, the authors of these studies

appeal to the early Keynesian notion that, when the economy has slack, fiscal expansions are less

likely to crowd out private spending. Using U.S. data, Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012) find that

fiscal multipliers associated with government spending fluctuate widely across the business cycle:

from 0–0.5 during expansions to 1–1.5 during recessions (Figure 9).

23

However, in this literature, the

definition of fiscal shocks and the measure of slack are important. Owyang, Ramey, and Zubairy

(2013), using a narrative approach to derive a different measure of government spending shocks,

find no evidence of higher multipliers during high-unemployment periods from U.S. data going back

to 1890, although they do find such a result for Canada.

23

Other studies, including Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2013), Baum, Poplawski-Ribeiro, and Weber (2012), Batini,

Callegari, and Melina (2012), and IMF (2012d), find some supporting evidence for other OECD economies. It is worth

noting that, according to these studies, multipliers sometimes vary substantially across countries and across different

fiscal instruments.

Figure 9. United States: Historical Multiplier for Total Government Spending

Source: Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012).

Note: Shaded regions are recessions defined by the NBER. The solid black line is the cumulative multiplier, which indicates effect

on GDP of a 1 percent of GDP increase in government spending. Dashed lines indicate the 90 percent confidence interval.

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 05

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

35. A separate, but related, issue is that fiscal policy may have more persistent effects

during periods of economic slack. While this is still the subject of some debate, DeLong and

Summers (2012) argue that, during the recent long-lasting slump, a process of “hysteresis” links the

short-term cycle to the long-term trend, so that a temporary change in unemployment has a

tendency to become permanent. According to this view, in a depressed economy, low rates of

investment imply a deterioration of physical capital, human capital declines as workers without

employment lose their skills, and the long-term unemployed face a declining likelihood of being

rehired. All of these factors influence potential output. Thus, if hysteresis effects are stronger during

slumps, then fiscal policy is likely to have more persistent effects on economic activity.

Expansionary contractions and confidence effects

36. Before and early on in the crisis, a number of researchers and policymakers argued

that positive confidence effects could dominate the adverse mechanical effects of cuts in

spending or increases in revenues, and lead to “expansionary fiscal consolidations.” However,

recent research suggests that previous findings of expansionary effects are sensitive to how fiscal

consolidation is defined (IMF, 2010b; Guajardo, Leigh, and Pescatori, 2011), and that the most

famous episodes of expansionary contractions observed in Europe in the 1980s and 1990s were

typically driven by external demand more than by a surge in internal private demand on the back of

confidence effects (Perotti, 2011). While more evidence needs to be gathered, it does not appear

that confidence effects have played a major role in this crisis. In particular, a key channel through

which expansionary effects could occur––namely by decreasing risk premia on sovereign bonds and,

thereby, on domestic lending rates––has not been at work, since risk premia were already quite low

in most advanced economies when consolidation took place, although they were elevated in several

peripheral euro area countries.

37. The scope for confidence effects to offset the direct Keynesian effects of fiscal policy

could also be hampered by the reaction of spreads to economic activity. There is some

evidence that sovereign spreads appear to react strongly to output growth as well as to changes in

the fiscal accounts (Cottarelli and Jaramillo, 2012; Romer, 2012). These results––suggestive as they

are––imply that a fall in fiscal deficits associated with fiscal consolidation could, perversely, trigger a

rise in sovereign borrowing costs if the impact of lower growth dominates, thus contributing to a

further fall in output. In this case, confidence effects would reinforce rather than offset the direct

effects of fiscal policy (see also the next section on the design of fiscal adjustment plans).

B. Fiscal Policy Implementation

38. For fiscal policy to be truly effective as a countercyclical tool, a number of additional

conditions, beyond positive fiscal multipliers, need to be satisfied. First, fiscal authorities should

have room to maneuver so that the increase in debt associated with a fiscal expansion does not

trigger a sovereign debt crisis. As the previous section argued, the crisis has shown that this is a

concern for a number of AEs. Second, fiscal authorities should have the ability to respond to

economic developments in a timely and temporary manner. Prior to the crisis, a widely-held view

was that fiscal policymakers, unlike monetary policymakers, would respond too slowly to be able to

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

deliver fiscal stimulus during a recession.

24

In addition, there was suspicion that stimulus introduced

during downturns would not be subsequently fully withdrawn, leading to overheating (Taylor, 2000)

and a ratcheting up of government debt over time. This subsection assesses what lessons have

emerged from the crisis about these important real-world issues. Given the recent (and, in some

economies, ongoing) nature of the crisis, any lessons are necessarily tentative.

Fiscal response lags: this time was different

39. The experience with discretionary fiscal policy since the crisis demonstrates that

policymakers can rapidly deploy substantial fiscal stimulus. After the failure of Lehman Brothers

in September 2008, it became clear that the global financial sector was suffering a shock of a

magnitude unprecedented in the postwar period. Fiscal policymakers in most advanced economies

passed fiscal stimulus packages by the end of 2008—a relatively fast pace for discretionary fiscal

policy, albeit slower than that of monetary policy (Figure 10).

24

Fiscal policy lags would arise because of delays both in assessing the need for stimulus after the onset of a

downturn, and in legislating and implementing countercyclical legislation.

Relatedly, Romer and Romer (1994)

concluded that U.S. discretionary fiscal policy played a minor role in ending recessions from 1950 to the early 1990s,

while monetary policy played a substantial role. Auerbach (2009) and Auerbach and Gale (2009) find that U.S.

discretionary fiscal activism increased during the 2000s.

Figure 10. Advanced Economies: Time Lag Between Lehman Failure and

Fiscal Stimulus Packages

(In Months)

Sources: International Institute for Labor Studies (2011), IMF (2010a), and IMF staff estimates.

Notes: Figure indicates time in months until first fiscal stimulus package announced after September 15, 2008. Stimulus measures

announced prior to that date, are not included in the chart.

0123456

United States

Finland

Singapore

Norway

Canada

Sweden

Portugal

Israel

United Kingdom

Spain

New Zealand

Netherlands

Korea

Italy

HongKong

German

y

Denmark

Japan

France

Australia

Response time in months (after Sept. 15, 2008)

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

40. In the United States, the country at the center of the global financial crisis,

discretionary fiscal policy had already started in February 2008. The Economic Stimulus Act

provided around US$150 billion in stimulus to the economy in the same year, primarily through

refundable tax rebates targeted to low- and middle-income households, who started receiving the

payments in May 2008. This occurred even before there was an accepted consensus that a recession

had begun or would materialize (Auerbach, Gale, and Harris, 2009).

25

In July 2008, a new tax credit

for first-time homebuyers was also passed to target weakness in the real estate sector.

41. There was heterogeneity across countries in the size and time profile of stimulus

measures. Of the advanced economies in the Group of Twenty (G-20), Australia, Canada, Germany,

Japan, Korea, and the United States launched fiscal stimulus packages following the Lehman episode

that exceeded 3 percent of 2008 GDP in discretionary stimulus over 2009 and 2010 (IMF, 2010a). The

combined U.S. fiscal stimulus from all measures, including the American Recovery and

Reconstruction Act (ARRA) passed in February 2009, amounted to 4.6 percent of 2008 GDP over

2009–10. The United Kingdom deployed nearly all its stimulus through temporary tax cuts in 2009.

Australia also deployed significantly more fiscal stimulus policy in 2009 than in 2010. Canada,

France, and Japan delivered stimulus fairly evenly over the two years, while Germany and the United

States delivered more fiscal stimulus in 2010 than in 2009.

Fiscal response lags: why was this time different?

42. A number of factors explain the relatively rapid fiscal response during the crisis. The

size of the shock to the world economy was, arguably, the primary factor. Another plausible

explanation for the increased reliance on discretionary fiscal policy stimulus during the crisis was the

ZLB constraint on monetary policy. Fiscal authorities especially stepped up their activism in the final

months of 2008, around the time that nominal policy interest rates were coming close to the ZLB.

Moreover, the shift toward discretionary fiscal stimulus in many economies coincided with a

multilateral drive for global fiscal stimulus. On November 15, 2008, a G-20 communiqué urged a

coordinated policy response to the crisis, including “fiscal measures to stimulate domestic demand

to rapid effect, as appropriate, while maintaining a policy framework conducive to fiscal

sustainability” (G-20, 2008). This was followed by a range of fiscal policy proposals from the IMF

(Spilimbergo and others, 2008). Global coordination arguably helped policymakers recognize the

positive spillover effects of expansionary fiscal policy.

25

The Business Cycle Dating Committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research announced in December 2008

that the U.S. had entered recession in December of the previous year, when payroll employment started declining

according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics large survey of employers. The first quarterly decrease in real GDP

occurred in the third quarter of 2008. As late as March 2008, the Congressional Budget Office (2008) forecast growth

rates of GDP of 1.9 and 2.3 percent for 2008 and 2009, respectively.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Fiscal response lags: which measures were implemented fastest?

43. Discretionary fiscal packages contained several types of stimulus measures, with some

policies being implemented faster than others. As Table 1 reports, the policies with the fastest

implementation times were tax relief measures, such as targeted tax rebates in the United States,

value-added tax (VAT) cuts in the United Kingdom, and car scrappage schemes, such as those

implemented in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Transfers programs,

such as extensions and expansions of unemployment benefits and other social benefits had short to

moderate lags. Finally, public infrastructure investments were implemented with longer lags arising

from project evaluation and procurement procedures. Bringing forward pre-planned capital

expenditures also mitigated this problem, as in the case of stimulus programs implemented in

Belgium, France and the United Kingdom. Also, as the slump persisted for longer than expected,

protracted outlays, such as those related to infrastructure projects, would have been timely and at

the same time supportive of future growth. Assessing the specific impacts of these varied fiscal

measures on economic activity is the subject of ongoing research.

26

26

Feldstein (2009) and Shapiro and Slemrod (2009) calculate modest effects on aggregate U.S. consumption from

the rebates of February 2008, which could reflect the fact that the payments reached a wide range of households, not

all of whom were tightly credit constrained. Mian and Sufi (2012) find that the U.S. car scrappage program led to an

increase in car sales, although over a short horizon, as purchases were brought forward. Chodorow-Reich and others

(2011) show strong (regional) effects from U.S. federal aid to the states.

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

Table 1. Selected Fiscal Stimulus Measures Used by Advanced Economies

Sources: Budget documents, and Saha and von Weizsäcker (2009).

44. Finally, it is worth recognizing the sizeable role that automatic fiscal stabilizers, the

size of which varied across countries, played during the crisis. Figure 11 reports a breakdown of

the overall fiscal expansion across discretionary measures and automatic stabilizers for G-20

advanced economies. For this sample, it appears that countries with smaller automatic stabilizers

provided larger discretionary stimulus.

27

27

Relatedly, Auerbach (2009) argues that for the United States fiscal experimentation during the crisis was aided by

the increasing fiscal activism of the preceding decade, in turn partly motivated by a decline in automatic stabilizers.

Aizenman and Pasricha (2011) suggest another possible reason for the large discretionary fiscal impulse of the U.S.

government is that it helped offset a strong contraction in fiscal expenditures at the state and local level.

Type of measure Selected country examples Full impact Target Duration

France2009:€1000ormore,dependingonnewcar

Germany2009:€2500incentive

UK2009:£2000incentive

USA2009:$3500or$4500,dependingonnewcar

UK2008:TemporarycutstobasictaxrateandVATrate

USA2008:One‐timerefundabletaxrebates.2009:Two‐year

refundablerebatesforlowincomehouseholds;one‐yeartaxcutfor

medium‐incomehouseholds.2010:Payrolltaxcut

Austria2009:Pre‐plannedtaxreformbroughtforwardbyoneyear,

incometaxcutsformediumtohighincomeindividuals

Germany2009:Riseintax‐freeallowanceandcutinbasicrate

Sweden2009:Cutsincorporatetax,socialsecuritycontributions

andpersonalincometax

Belgium2009:Higherunemploymentandothersocialbenefits

USA2009:Extensionofunemploymentbenefits,fundingfor

medicalcareandnutritionsupportforlowincomehouseholds

Netherlands2009:Energyefficiencyandgreengrowthmeasures

Sweden2009:School,vocationalandresearchfunding

USA2009:Renewableenergy,transferstostatesforeducation

Australia2009:Schoolbuildingprogram

Belgium2009:Newandacceleratedpublicinvestments

France2009:Centralandlocalgovernmentinvestmentsbrought

forwardfrom2010to2009

Germany2009:Accelerationoftransportationandother

infrastructurespending

Spain2009:Publicinvestmentinmunicipalworks

USA2009:Newtransportationandotherinfrastructurespending

Carscrappageschemes

(replacingoldcarswith

fuel‐efficientvehicles)

1‐3months

Fromafewmonths

touptotwoyears

(oftenextended)

Automobile

industry

Lowandmedium

income

households;

consumption

Some

immediate,

somephasedin

overtime

Various

Envisionedtobe

permanent;Austria

raisedupper

incometaxratein

2013

Permanenttaxcuts

Temporarytaxcutsand

transfers

Immediate 1‐2years

Infrastructure

investment

2009for

accelerated

investments,

2010‐2011for

newprojects

Educationand

transportation

infrastructure

1‐2yearsfor

accelerated

investments,3‐6

yearsfornew

investments

2009‐2010

Expansionoftargeted

transferprograms

Liquidity‐

constrained

households

Mostofspending

within3‐5years

Governmentpurchases

ofgoodsandservices

Mostly2009

and2010,upto

2012forUSA

Educationand

greenenergy

1‐3yearsfor

education,1‐8years

forR&D

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

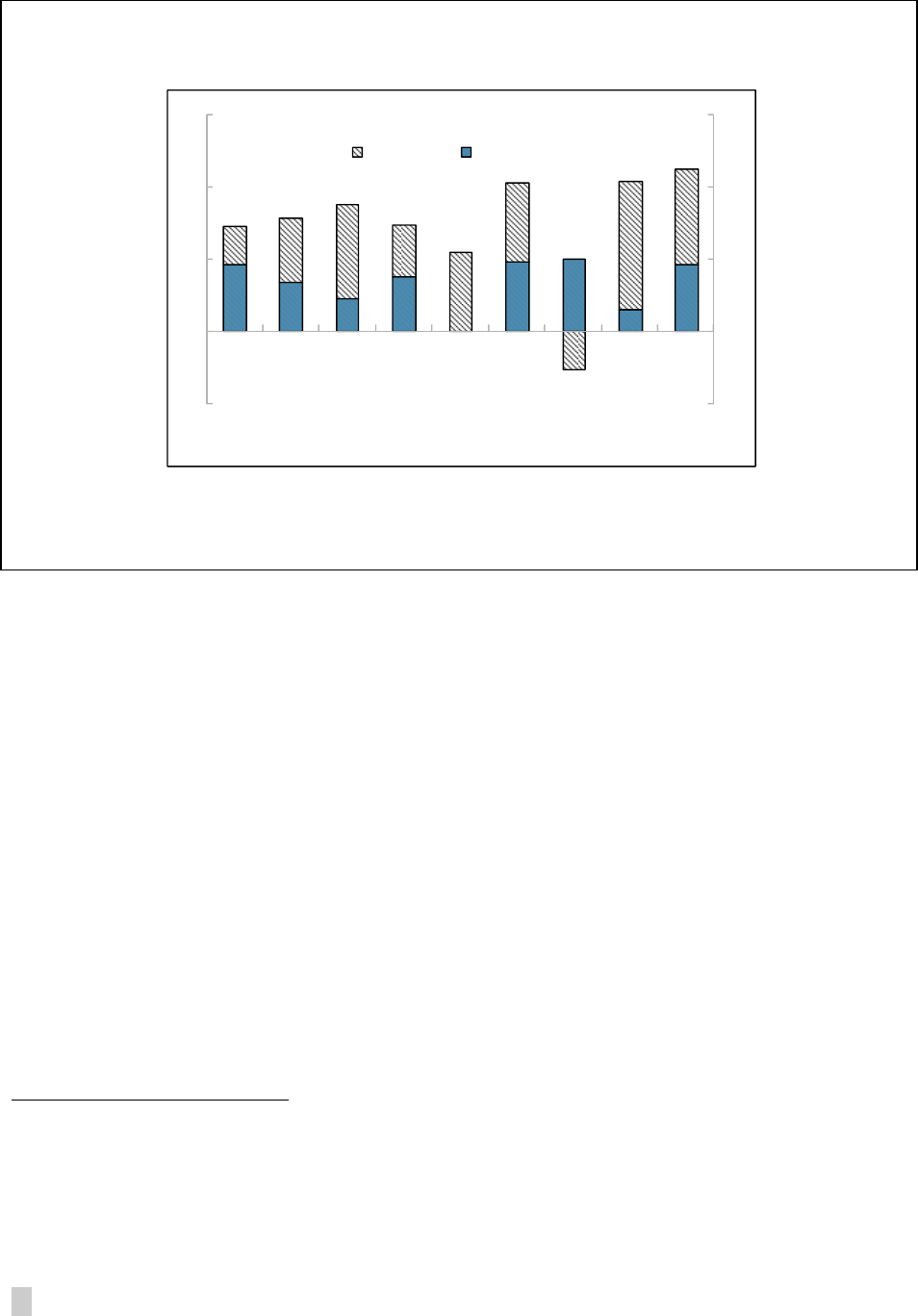

Figure 11. G-20 Advanced Economies: Contributions of Discretionary Stimulus and Automatic

Stabilizers to the Primary Fiscal Deficit, 2009–10

(Percent of 2008 GDP)

Sources: IMF staff calculations based on WEO and Fiscal Monitor (IMF, 2010a) data.

Notes: Sample comprises advanced countries in the G-20. Contribution of automatic stabilizers is calculated as the residual change

in the primary deficit after accounting for the discretionary stimulus. Staff calculations indicate that Korea’s automatic stabilizers

damped the change in the primary deficit over 2009–10, consistent with strong nominal GDP growth.

Reversibility of stimulus

45. The crisis also provided numerous examples of policymakers undertaking

discretionary fiscal stimulus measures that, according to the evidence available thus far, were

largely temporary. Temporary tax cuts and transfers were planned to be the largest single

component of stimulus programs for the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Belgium. The United

Kingdom ended the temporary VAT tax cut at the end of 2009, and actually raised the VAT rate in

2010 above its precrisis level as part of its fiscal consolidation program.

28

Car scrappage schemes,

used in several countries, were often extended, but eventually ended. Similarly, in the United States,

as Figure 12 reports, fiscal stimulus took the form of a series of temporary fiscal packages. One-time

tax rebates provided to low- and medium-income households in early 2008, and the rebates and

transfers to these households and to social security recipients as part of the ARRA, were withdrawn

as scheduled. Some temporary measures were extended in a limited fashion when economic activity

remained sluggish: owing to persistently high unemployment, the payroll tax cuts implemented in

2010 were extended twice, before being terminated at the end of 2012.

29

28

By contrast, permanent tax cuts and transfers accounted for a larger share of the fiscal stimulus packages in

Germany, Austria and Sweden (Saha and von Weizsäcker 2009).

29

At the same time, the precrisis tax cuts passed under the Bush administration, primarily for reasons other than

countercycical concerns (Romer and Romer, 2009), were largely made permanent.

-5

0

5

10

15

-5

0

5

10

15

AUS

CAN

FRA

DEU

ITA

JPN

KOR

GRB

USA

Automatic Discretionary

REASSESSING FISCAL POLICY

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27