Health Safety & Work-Life Service Center

Safety and Environmental Health Division

Annual Safety Report

Fiscal Year 2015

This report describes the frequency and characteristics of mishaps associated with shore based units,

cutters, aviation/aviation support and boats. Off-duty mishaps, motor vehicle, and sports related injuries

are also summarized and described.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Table of Contents Page 2 of 72

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 2

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3

Overview and Mishap Summary .................................................................................................... 5

Cutter Operations .......................................................................................................................... 11

Boat Operations ............................................................................................................................ 19

Shore Operations ........................................................................................................................... 25

Deployable Special Forces (DSF) Operations .............................................................................. 30

Marine Environmental Response and Marine Inspection ............................................................. 32

Recreational and Off Duty Mishaps ............................................................................................. 33

Motor Vehicle Mishaps................................................................................................................. 35

Laser Illumination Mishaps .......................................................................................................... 36

Environmental & Occupational Illness Mishaps .......................................................................... 37

Safety and Environmental Health Resources ................................................................................ 40

Aviation Operations ...................................................................................................................... 42

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Introduction Page 3 of 72

Introduction

I am pleased to present the third USCG Annual Safety Report.

As you may notice, the title of this year’s report has changed to

reflect the purpose and intent of the report. My view is that this

report should not only report mishap information but it should

also be an avenue to promote the Coast Guard’s Safety

Management System (SMS) and to share important and relevant

safety information. Since the release of the FY14 HSWL Service

Center Annual Mishap Analysis Report, there have been two

changes to the Coast Guard’s Safety Management System (SMS)

that I would like to highlight. The development of Tactics,

Techniques, and Procedures (TTP) documents and establishment

of Safety and Risk Management (SARM) councils are among

the most significant and recent developments in the CG SMS.

HSWL SC Safety and Environmental Health (SEH)

professionals and subject matter experts from CG field units

currently collaborate to develop TTPs for specific topics

contained in the Safety & Environmental Health (SEH) Manual. FORCECOM publishes TTPs

and makes them available at the following link: HSWL SC (se) TTPs. To date, eight TTPs have

been completed, seven TTPs are in different stages of development in FY 16, and seven are

scheduled for completion in FY17.

The implementation of SARM councils has reached 54% completion in 2015. The intent of these

councils is to enhance AOR SEH programs by identifying, assessing, and addressing local

problem areas through recommendations of corrective measures and/or policy development. The

SARMs can be significant sources for sharing information and elevating innovative risk

management solutions to the Risk Management Steering Committee (RMSC) headed by CG-

113. The RMSC acts as a clearing house to address emerging cross-directorate SEH issues under

the SMS umbrella.

In addition to the recent developments in the CG SMS, we have learned many lessons through

the analysis of mishap information contained in our electronic mishap reporting systems (e-

MisReps and e-AVIATRs). Two salient findings are the failure to implement a unit specific

Mishap Response Plan (MRP) and establish a unit level Permanent Mishap Board (PMB) at

many units. Implementing and exercising MRPs, including the PMB, ensures coordinated efforts

after a mishap, secures evidence integrity and preservation of the mishap scene, and ultimately

assures the quality of data collection and of the final mishap analysis.

Another significant finding from our examination of enterprise safety practices reveals that,

despite a mandated annual requirement, usage of the Unit Safety Assessment Tool (USAT)

remains low. USAT is an online tool customizable to unit specific needs, allowing

documentation of self-inspections and the ability to track SEH deficiencies to completion.

Moreover, it is a basic and necessary resource for Commanders to promote a safety conscious

culture.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Introduction Page 4 of 72

Lastly, the e-MisReps system is another element of the CG SMS that augments units’ ability to

maintain vigilance on their unit and/or community’s safety posture. Commanding Officers and

Officers-in-Charge can utilize the e-MisReps system to obtain current reports on mishap and

injury data. These reports raise awareness of safety concerns at their unit and of corrective

actions. In general, the e-MisReps system raises members’ awareness of conditions

compromising safety in CG work and living environments.

As you progress through this report, you’ll see that key takeaways are provided at the beginning

of each section. Communities should refer to their respective sections to review details and

analysis. I would like to offer these noteworthy cross-community observations from the 2015

Annual Safety Report:

Mishap analyses identified “judgment” as the most frequently cited contributing factor.

Our analysis revealed that CG members often use poor judgment when they feel

pressured to continue with a mission. The effect of using poor judgment has significant

consequences on the development of risk acceptance. In the operational environment,

members are exposed to risk on a regular basis. After the exposure, it is natural to

evaluate the experience and decide whether or not to take that risk again. If the exposure

did not result in any harm, eventually, the risk becomes “acceptable.”

While there were more on-duty mishaps, off-duty sports injuries accounted for the

majority of hospitalizations, lost work days, and days of restricted work. Unit leaders are

best positioned to reduce off-duty sports injuries by stressing the importance of

mitigating hazards even during off-duty hours, in recreational and sports activities.

Laceration and electric shock injuries were prevalent across several communities. In

these instances, analyses revealed frequent lack of job hazard analysis, incorrect

procedures, and using wrong tools for the job.

Lastly, slips, trips and falls were identified as the leading type of mishaps. Inadequate

lighting, wet and slippery surfaces, obstructed aisle and walkways, ladders, unguarded

openings, and elevated work surfaces were listed as contributing factors. In these cases,

daily unit self-inspections is one of the most effective ways to reduce this type of mishap.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Overview and Mishap Summary Page 5 of 72

Overview and Mishap Summary

Key Takeaways

FY 15 total mishaps remained relatively the same when compared to the 10-year

average; cutter and boat units experienced a 15% and 21% decrease in the number of

mishaps respectively when compared to the 10-year average; however, Shore remained

relatively the same (within one standard deviation).

Cutter damage costs doubled from FY14 to FY15 ($2.0 to $4.1 million).

Injury rates increased across all categories from FY14 to FY15, with the largest

increase found on Cutters (1.94 to 2.59). Figure 1.3.

The number of reported mishaps may not reflect the actual number of mishaps

occurring in the field. Underreporting is recognized and we encourage commands to

accurately report mishaps.

This chapter provides an overall view of mishaps CG-wide and narrative summaries of all class

A and B mishaps. A more in-depth review of off-duty, recreational and motor vehicle mishaps

are covered separately in later chapters.

Graphic Representation of Annual Reported Mishaps:

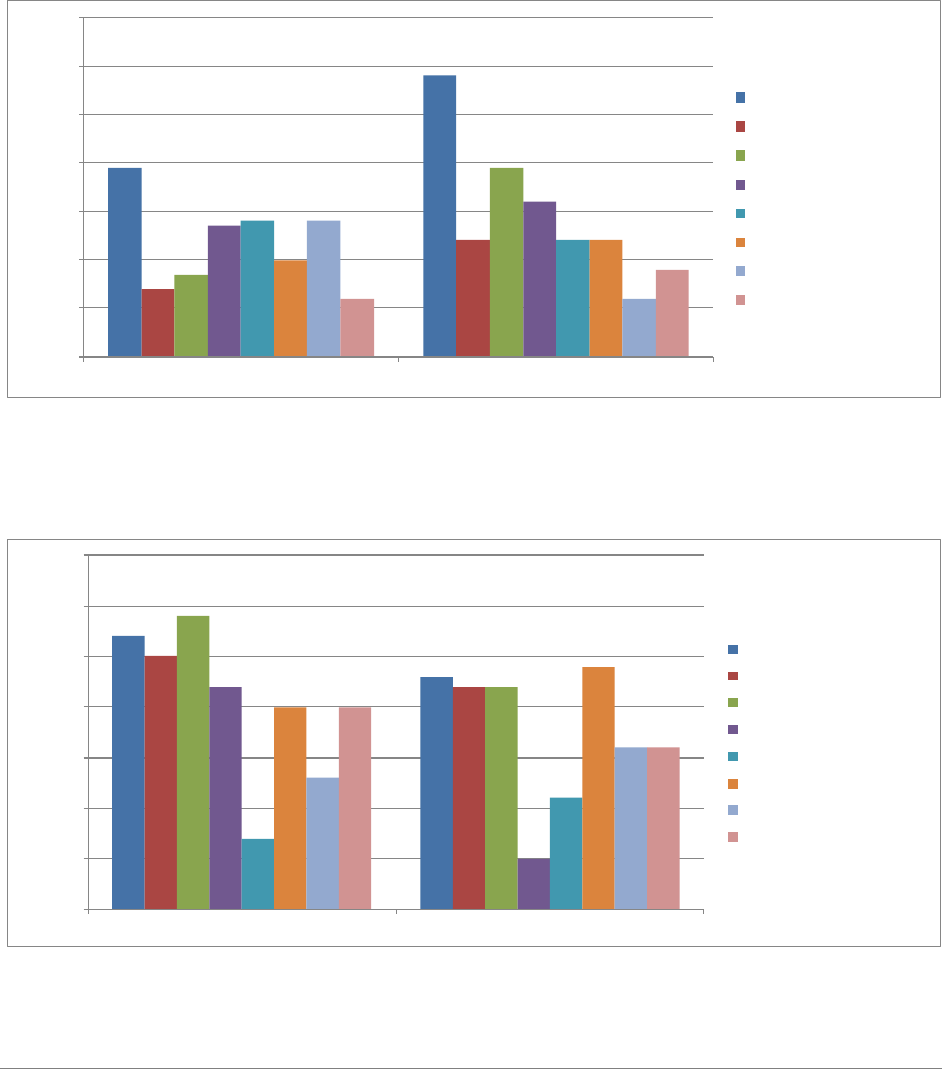

Figure 1.1: Number of Mishaps Reported FY05-FY15: Total count of all mishaps by community

587

552

583

596

623

487

585

608

549

519

480

805

894

886

891

827

790

713

738

809

623

634

958

797

715

715

546

551

559

595

695

576

567

685

677

675

699

683

657

615

584

654

611

649

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Mishaps Reported

Cutters

Boat Units

AirSta / Aviation Support

Shore Units

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Overview and Mishap Summary Page 6 of 72

10 Year Average of Total

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Mishaps

Shore Units

654

36

649

Air Stations & ALC

671

127

567

Boat Units

798

83

634

Cutters

569

40

480

Table 1.1: FY15 Mishaps compared to the 10 year mishap average (FY05 - FY14)

Figure 1.1 showed that total mishaps in FY15 remained stable when compared to the 10-year

average (2,330 in FY 15 vs. 2,630 as the 10-yr average). Cutter and Boat unit mishaps decreased

in FY15 (1.98 and 2.25 standard deviations from the 10-year average respectively). A review of

FY15 mishap data revealed a total of 16 Class A and Class B mishaps, (Aviation In-flight is

discussed in a later chapter) summarized below:

Class A - Operational:

Fatality – Civilian: The crew of a boat heard and felt the hull impact an object in the water. The

crew conducted a search of the area and found a small inflatable raft. There were no other objects

or persons located in the area. The crew finished the patrol and returned to base. The following

morning, local law enforcement recovered a deceased body in the vicinity of the impact. Three

days later, CGIS investigators working with local law enforcement determined that the victim

appeared to have been struck by a Coast Guard 33-foot SPC-LE.

Property Damage – Loss of Boat: A CGC was directed to rendezvous with a second cutter to

transfer 50 migrants. During the transfer, a large swell lifted the stern of the first cutter and water

came over the bow of the boat. The crew of the second cutter and the boat crew on the first cutter

started yelling “water over the bow”. The coxswain brought the jet drives bucket back slightly to

move the bow away from the cutter and then brought the bucket forward and increased throttle to

lift the bow through the wave. During this action water continued to come over the starboard

bow, causing the boat to roll to starboard and capsize. Total property damage amounted to

$390,466.12.

Class A - Non-Operational Vehicle/Vehicle Related:

Fatality – Active Duty: A group of Coast Guard members from a CGC departed a local

establishment. Upon leaving at approximately 0130, three members decided to cross a high-

density traffic highway on foot, the South Padre Island Drive. The visibility at that time was

reduced by low-lying fog. As the group proceeded across the highway, a van traveling

northbound at approximately 45 mph collided with the last member of the group.

Fatality – Active Duty: Boat Station. On the evening of 21 September 2015, three out of four

mishap members were at a fellow shipmates house socializing and drinking alcohol. The

designated driver reported arriving at the house at approximately 1900 and was asked to drive

the other three members to the store. The driver was handed keys to an F250 Ford truck

belonging to another mishap member.

On the return trip from the store, the vehicle came around sharp left-hand turn (posted at 30mph)

in the road. The vehicle encountered deer in the road. As the driver attempted to avoid the deer,

the PMVs right tires got off the paved surface onto loose gravel causing the PMV to “fishtail”.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Overview and Mishap Summary Page 7 of 72

As the PMV came back onto the paved road surface, it regained full traction and hit an

embankment on the opposite side of the road, flipping onto the passenger side of the vehicle and

coming to rest in the oncoming lane. Three members reported hanging in the vehicle by their

seatbelts and were able to unclip and climb out of the driver’s side window. One member, who

had been seated in the front middle seat, reported difficulty unclipping seat buckle. Upon looking

down at the buckle, member noticed they had unclipped front passenger seat buckle and not their

own.

Upon exiting the vehicle, the same member reported noticing member from front passenger seat

(deceased) had suffered significant injuries, was partially ejected, draped over passenger side

door, and upper torso was lying underneath vehicle.

Fatality – Active Duty: A member assigned to a CGC was traveling home in a motor vehicle

when he lost control of his vehicle, which went off the road and struck a tree. Member died

instantly and the passenger (non-Coast Guard civilian) in the vehicle was MEDEVAC’d to the

hospital. She has since been discharged but confined to a wheel chair. The fatal mishap occurred

at 0100 hours on 31 August.

Class B - Operational:

Property Damage - Injury – Electrical Fire: CGC experienced an electrical fire in the #1

Switchboard. While cleaning in the auxiliary machinery space, a member heard three explosions

from the back of the #1 Switchboard. Upon investigation, fire and smoke was found coming

from the back of the switchboard. Nine personnel in the machinery space exited the space

without the use of EEBD’s and were seen by the onboard health service technician and TDY

physician assistant shortly thereafter for smoke inhalation. One member entered the space to

investigate and later donned an SCBA which ran low on air. Member was also seen for smoke

inhalation. All members were released without significant injury. Total cost of the switchboard

fire was reported as $629,178.

Injury – Active Duty: Member engaged in off-site Tactical Sustainment Training (TST),

member was acting as a role player during a use of force scenario. Member was in the prone

position and the Boarding Team Member (BTM) and Boarding Officer (BO) were attempting to

put the member in flex cuffs. The member went active and started to fight with the BTM. The

BO attempted to gain control of the member by delivering a knee strike to the side of the

member's right leg. As the BO's knee strike was about to make contact, the member switched to a

position on his side exposing his back. The knee strike landed in the middle of the member's

back, resulting in a possible lumbar fracture of his L1-L4 vertebrae.

Injury – Civilian: On 13 March 2015, at approximately 2330, a CG boat responded to a mayday

call from a 65-foot commercial fishing vessel reported aground north of the Port Everglades

inlet. Once on scene, the CG boat safely removed two people from the vessel. A third individual

attempted to jump to the boat and fell between the boats, resulting in initial reports of crush

injuries and lacerations to his leg and pelvis.

Property Damage – Grounding: On 20 February 2015, a CGC was underway, transiting from

Southwest Harbor, ME to Jonesport, ME. At approximately 1745, the cutter struck something

hard while passing through Petit Manna Bar.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Overview and Mishap Summary Page 8 of 72

Property Damage – Grounding: After completing surf training off of Benson Beach, an MLB

was transiting inbound across Peacock Spit in 12-14 foot Surf, winds 25 - 30 knots out of the

SSW, visibility 04 nautical miles, when they struck a submerged object, 500 yards west of the tip

of north Jetty.

Injury – Active Duty: While attempting to moor a CGC to a mooring buoy, injured members

hand was impaled by the rope installer hook when the line paid out uncontrolled. The members

hand was drug into the cutters chock before the line to the installer could be cut to free the

injured member’s hand.

Class B - Non-Operational Vehicle/Vehicle Related:

Injury – Active Duty: Member was riding a motorcycle southbound on US Highway 17 in

Georgetown, SC on Sunday, 02 November 2014 at 1705 local time, when he lost control of his

motorcycle.

Injury – Active Duty: Member was riding Motocross on a track when he wrecked, sending him

over the handlebars. The force was enough to break both femurs. The momentum of the accident

also caused the member to continue over the handlebars, impacting the ground with enough force

to cause spinal injury. The extent of the spinal injury is unknown.

Injury – Active Duty: While on liberty, crewmember was involved in an auto accident in which

his front right tire blew out cause his 1998 Dodge Ram 2500 to lose control and slam into a

walnut orchard. Member was towing a personal camping trailer at the time. His wife and son

were killed and he sustained multiple fractures to the lower half of his body.

Injury - Active Duty: Member was on leave in Panama near Panama City. The member was on

a tour bus that had brake issues and went over a 20 meter drop.

Figure 1.2: FY05 – FY15 Mishap Related Property Damage (millions): Aviation total for FY10 of

$142.8 million removed to allow for visual representation of other years (see Table 1.2 below).

$0

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

$60

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Property Damage Costs Iin Millions

Cutters

Shore Units

Boat Units

Aviation / AirSta

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Overview and Mishap Summary Page 9 of 72

Fiscal Year

Cutters

Shore Units

Boat Units

Aviation / AIRSTA

2005

$2.50

$0.34

$1.13

$23.43

2006

$4.93

$0.38

$1.75

$44.86

2007

$2.49

$0.58

$1.00

$10.22

2008

$2.94

$0.72

$1.10

$15.38

2009

$3.69

$0.75

$1.84

$9.33

2010

$2.65

$1.67

$1.46

$143.94

2011

$5.13

$0.64

$1.07

$4.66

2012

$4.23

$0.37

$0.91

$15.64

2013

$2.82

$1.39

$0.99

$7.90

2014

$2.00

$0.78

$1.12

$8.04

2015

$4.10

$0.48

$0.78

$5.23

Table 1.2: FY05 – FY15 Mishap Related Property Damage (millions)

Total reported mishaps remained almost the same in FY14 and FY15 (2,329 and 2,330

respectively) and property damage decreased slightly from $11.9 million to $10.6 million. Shore

units, boat units, and aviation/AIRSTA property damage decreased from FY14 to FY15;

however cutter damage doubled ($2.0 million in FY14 to $4.1 million in FY15). Additionally, a

134% decrease occurred in ground aviation and aviation support property damage while

reporting relatively the same number of mishaps (576 in FY14 vs. 567 in FY15).

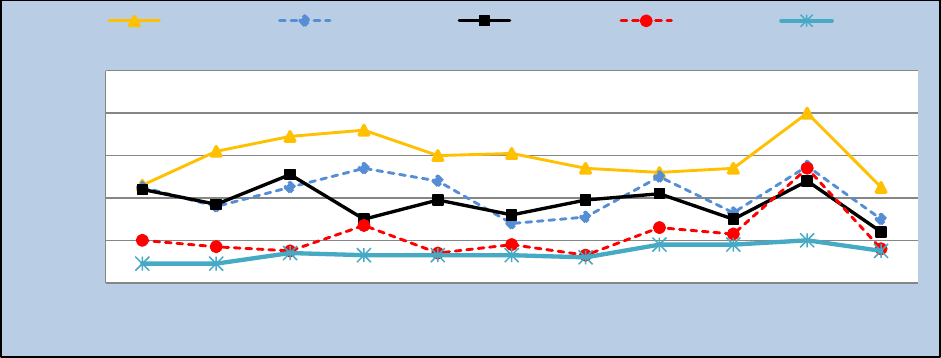

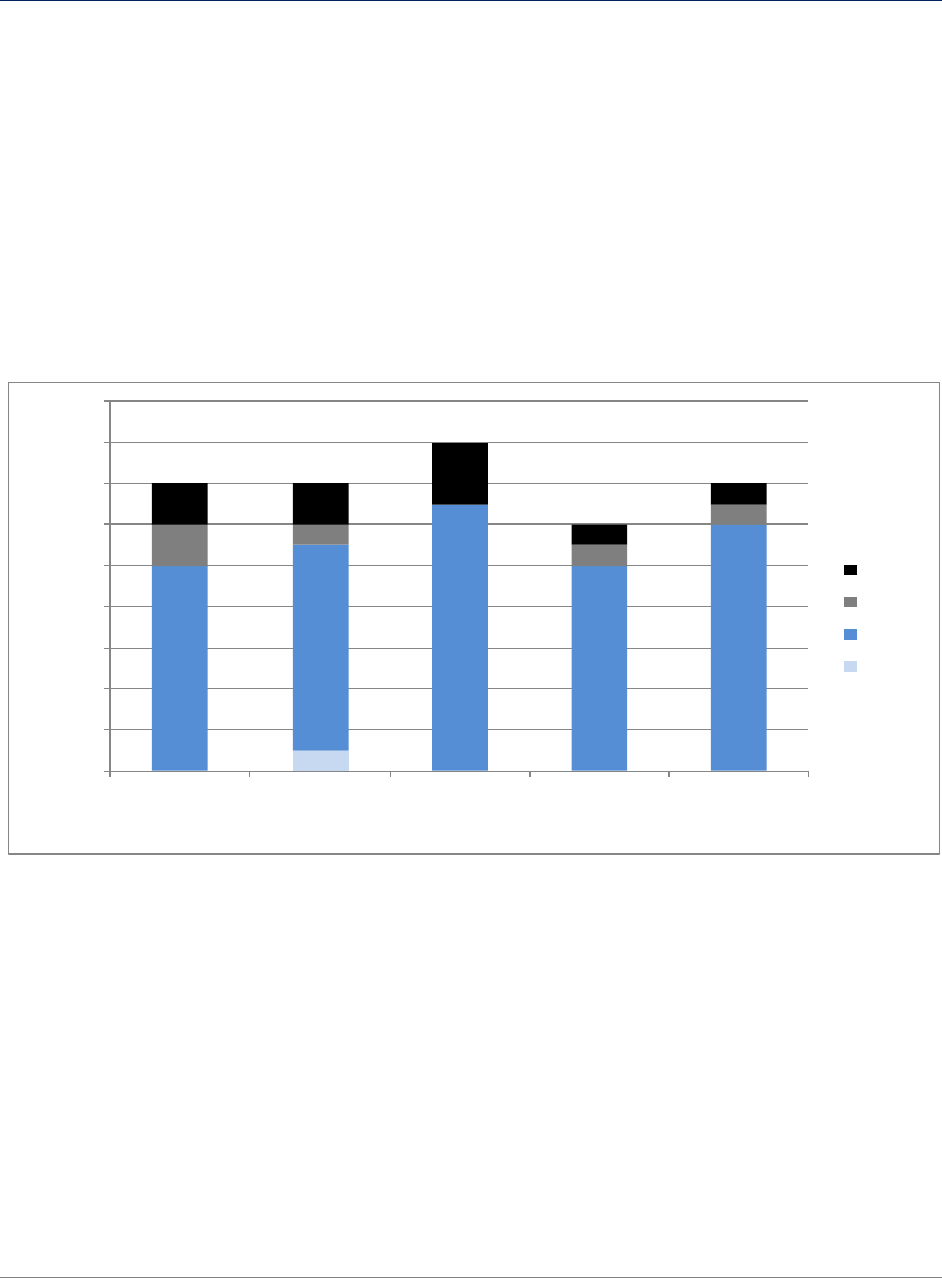

Figure 1.3: On-Duty Coast Guard Injury Rates: (On-duty cutter rates include inport and underway

injuries).

As shown in Figure 1.3, cutters had the highest injury rate from FY05 to FY15 except for FY13.

Shore commands (minus boat units and AIRSTA/aviation support) had the lowest injury rates

from FY05 through FY15. Injury rates increased across all categories from FY14 to FY15, with

the largest increase found on cutters (1.94 to 2.59).

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Injuries per 100 Personnel

Cutters

Boat Units

AirSta / Aviation Support

Other Shore Commands

Total CG Rate

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Overview and Mishap Summary Page 10 of 72

Figure 1.4: Coast Guard Lost Time Case Rates.

FY05-FY14 Average of

Injuries

Standard Deviation

FY15 Injuries

Shore Units

111

18

108

Air Stations & ALC

58

13

58

Boat Units

169

15

158

Cutters

199

29

206

Table 1.3: FY15 Injuries Compared to the FY05-FY14 average

Although cutters had the largest increase in injury rates (1.94 to 2.59), figure 1.4 shows that Lost

Time Cases (LTC) decreased, suggesting the injuries experienced were minor (First Aid) and not

associated with Lost Work Days (LWD). For all other communities, LTC decreased as well,

except for boat units which showed an increase from 0.47 to 0.61.

0.00

0.20

0.40

0.60

0.80

1.00

1.20

1.40

1.60

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Lost Time Case Rate per 100 Personnel

Cutters

Boat Units

AirSta / Aviation Support

Other Shore Commands

Total CG Rate

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 11 of 72

Cutter Operations

Key Takeaways

Cutter injuris occur more often inport than underway.

In FY15, 42% of mishaps (47/113) were associated with Enforcement of Laws and

Treaties (ELT) operations; and resulted in 40 % of injuries (31/78).

Aids to Navigation (ATON) operations accounted for 23% of on-duty injuries (18/78)

in FY15.

In FY15, fires accounted for 17% of operational mishaps. Person in water, HP

petroleum leaks and slips, trips and falls accounted for 21% of cutter mishaps.

Underway Mishaps

Figure 2.1: Cutter Mishap Rate by Class for FY15 (Underway/Operational)

Figure 2.1 exhibits mishap rates for FY15 for all cutter classes. As a cautionary note, we would

like to emphasize that the many factors that contribute to mishap rates in any given year for a

specific cutter class are not necessarily the same for all cutter classes. Factors contributing to

mishap rates depend on operational complexities, crew dynamics, equipment maintenance status,

platform maintenance, and safety procedures relevant to each cutter class.

A review of number of mishaps reported in FY15 by cutter class identified an unusually high

mishap rate on the WAGB/WLBB class (158.2). Paradoxically, this class of cutter was

associated with extremely low usage of resource hours during FY15.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 12 of 72

WMEC 270 (74.6), WLB (65.8), and WHEC (60.3) cutter classes exhibited the next highest

mishap rates. Usages of resource hours in these cases also suggest a possible relationship

between the low or moderately low usage of resource hours (approximately 50,000; 30,000; and

20,000, respectively) with a tendency for high mishap rates. However, we caution against

generalizing that low operational hours result in high mishap rates because data from many other

cutter classes do not support this association.

Examine figure 2.1, in particular rates and resource hours from WMSL (41.2), WMEC210

(47.5), WLR (41.3), WYTL (13.4), and WLIC (29.4), among others.

Figure 2.2: FY15 Cutter Mishaps by Mission (Underway/Operational)

Figure 2.2 shows the number of mishaps reported aboard all

cutter classes by mission types for FY15, revealing the majority

of underway cutter mishaps occurred during ELT and ATON

operations.

Forty-two percent of all mishaps reported (47 out of 113

mishaps) were associated with ELT, and 21% with ATON

missions (26 out of 113 reported mishaps). Fortunately, no

fatalities were reported in FY15. Note: these are frequency

counts of mishaps and do not account for operational hours.

Comparisons across missions are not valid because each

mission/platform is different and carries its own risks.

26

1

8

47

7

4

0

3

8

8

1

0

10

20

30

40

50

ATON

C&S

DO

ELT

IO

M+R

MER

OTHER

SAR

TRG

MI

Number of Mishaps

Mission

Description

ATON

Shore and Radio Navigation Aids

C&S

Command and/or Support

DO

Defense Operations

ELT

Enforcement of Laws and Treaties

OTHER

Other Not Listed

M+R

Maintenance and Repair

MER

Marine Environmental Response

MI

Marine Inspection

IO

Ice Operations

SAR

Search and Rescue

TRG

Training

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 13 of 72

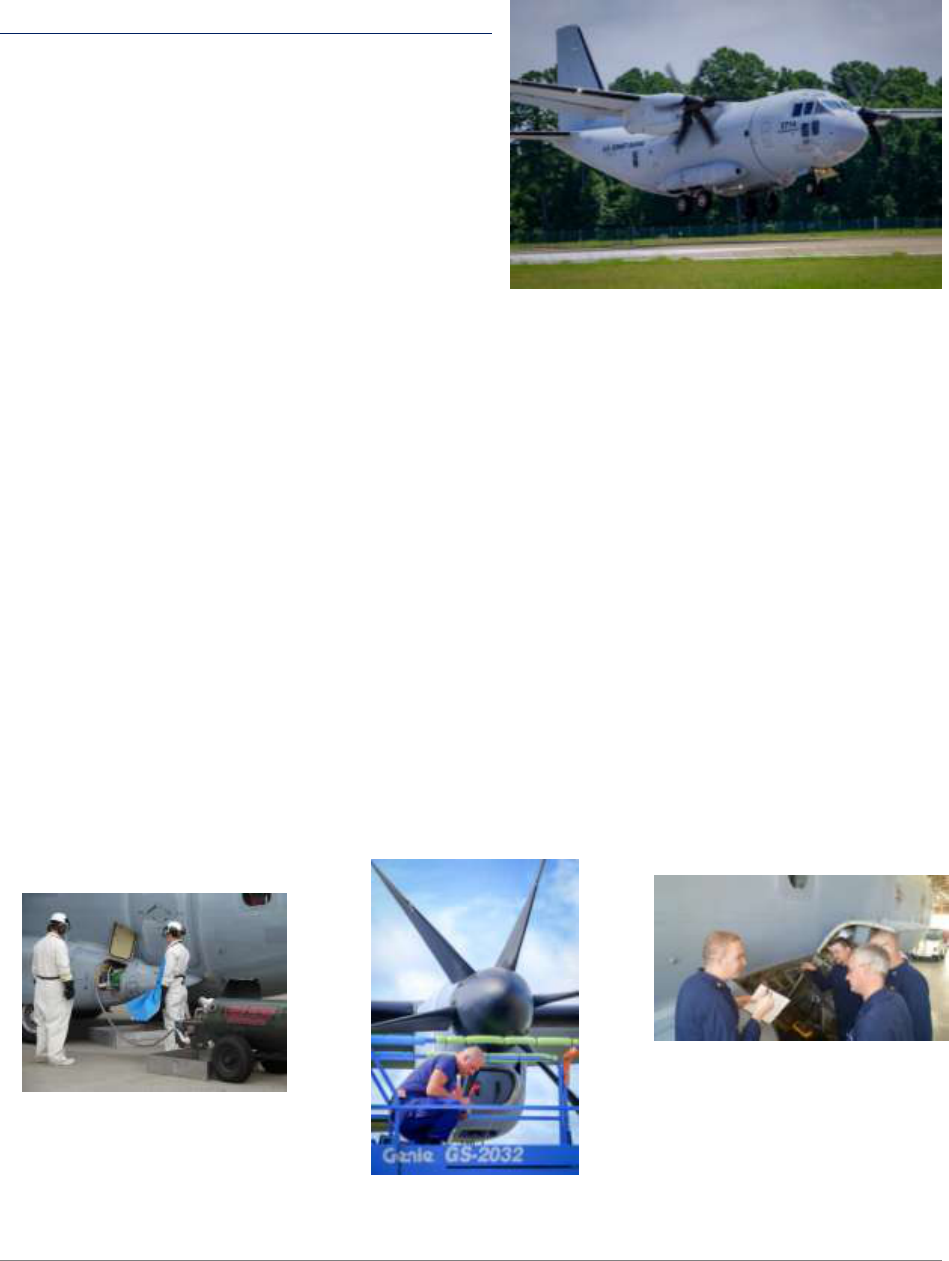

Figure 2.3: FY05 to FY15 Top Five Cutter Mishaps by Type (Underway/Operational)

The data reported in Figure 2.3 are frequency counts not rates, therefore limiting year to year comparisons

(i.e., operational hours were not used to normalize the data to a rate).

Figure 2.3 shows the FY15 top five most frequently reported operational mishaps. For the

purposes of contrast and comparison, data for the FY15 top five mishaps are also shown

retroactively from FY05 through FY14. Table 2.1 below, presents averages and standard

deviations calculated from FY05 through FY14 as well as total mishap reports for FY15.

Mishap reports for vessel collisions showed a decreasing trend from FY08 through FY13, a

temporary increase in FY14, and a return below the average in FY15. Person-In-Water (PIW),

High Pressure (HP), and Petroleum (Pet) leaks also exhibited sustained mishap frequencies near

their corresponding average frequencies throughout FY05-14. However, both mishap types

showed a noticeable decrease in FY15, falling below average values (eight FY15 total mishaps

reported in both cases). In contrast, the frequency of mishaps involving fires maintained a

sustained frequency near the 10-year average, including FY15.

To view a comprehensive report on fires aboard Coast Guard cutters, see Causative Factors of

Afloat Fires, on the Afloat Branch CG Portal page.

FY05-FY14 Average of

Type Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Types

Fire

19

8

19

Hp Pet Leaks

18

7

8

PIW

15

5

8

Slip Trip Fall

18

8

8

Collision Vessel

8

5

6

Table 2.1: Top Cutter Mishaps by Type, FY05 - FY14 (Underway/Operational)

15

12

13

9

1

5

1

2

4

15

6

18

15

26

13

7

12

11

18

26

33

8

16

19

11

24

17

12

10

11

7

20

8

9

25

13

29

18

14

21

27

10

14

8

10

20

17

32

22

7

26

29

16

15

19

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Number of Mishaps

Cutter Operational Mishaps by Type

Collision Vessel

Slip Trip Fall

PIW

Hp Pet Leaks

Fire

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 14 of 72

FY05-FY14 Average

Standard Deviation

FY15

UW Mishaps

126

16.0

113

UW Injuries

52

9.5

78

UW Lost Work Days

260

96.0

188

Cost (millions)

$3.34

$1.04

$4.10

Table 2.2: FY15 Cutter Crew Mishaps/injuries Compared to FY05 - FY14 (Underway/Operational)

Slips, trips and falls maintain yearly frequencies near the average value (Table 2.2 above),

mishap average of 18 from FY05-14, although in FY15 the trend was interrupted with a

noticeable decrease well below the average (eight total FY15 mishaps reported).

Figure 2.4: Cutter Injury Rates, FY05-FY15 (Underway/Operational)

Underway Injury rates increased in FY15 to 5.4 from 4.6 in FY14.

Analysis of Injuries

The injuries reported in this section are frequency counts and not rates. Information in this

section is from analysis of data from e-MisReps. The injuries discussed occurred while

underway.

Injuries by Mission: In FY15, there were 106 injuries inport (Table 2.3) and 78 underway

/operational (Table 2.2). Of the underway injuries, 17% (13/78) occurred during IO operations

on WAGB 399 class vessels, 15% (12/78) occurred during ELT

operations onboard WMEC 270 class vessels, and 15% (12/78)

occurred during DO operations aboard WPB 110 class vessels. Other

operations where injuries occurred were noted during ATON, C&S,

M+R, MI, SAR and training missions.

12.2

9.1

14.7

13.5

14.8

13.7

10.6

20.5

14.6

15.7

20.2

-

5.0

10.0

15.0

20.0

25.0

-

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

450,000

500,000

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Injuries per 100K Hours

Cutter Resource Hours

Cutter Resource Hours

Underway Injury Rate per 100K Op Hours

FY15 Cutter Underway Injuries

CUT/LACERATIONS

20

INHALATION

14

IRRITATION

12

BRUISE

9

SPRAIN

5

FRACTURE

5

OTHER

13

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 15 of 72

Cutter Injuries: Cuts / Lacerations were the highest reported injury accounting for 26% (20/78)

of the total cutter injuries, and of those, 40% (8) were caused while working on equipment

(includes pinching fingers and cuts while using small power tools, hand held tools, buoy deck

work, etc.). The common factor was performing maintenance on cutter equipment. Thirty-five

percent (7) of the cuts injuries were to the head or extremities from knife edges on hatches, water

tight doors or scuttles, and ladder wells. These occurred while members were transiting through

watertight doors/hatches or falling in ladder wells. Twenty-five percent (5) of cuts/lacerations

were caused by knives/box cutters. Opening packages and food preparation was the common

factor in knife-related mishaps.

Inhalation was responsible for 18% (14/78) of cutter injuries, and of those 71% (10) were due to

a single class Charlie fire. Four injuries were from smoke inhalation during an incinerator fire.

Irritations accounted for 15% (12/78) of injuries, and of those, 83% (10) were caused by crew

members’ eyes coming in contact with lasers from shore and other boats while conducting

operations underway.

Bruising accounted for 12% (9/78) of injuries from contact with doors, hatches, scuttles and

knife edges, during a vessel list, encountering high seas, unsecured equipment or members

attempting to transit ladders. Sprains were responsible for 6% (5/78) of injuries caused by

slips/trips/falls, and while transiting ladders.

Figure 2.5: Top Five Causal Factors: FY05-FY15 (Underway/Operational)

Numbers in brackets depict number of operational mishaps (per year). Each reported mishap can have

multiple causal factors.

In looking at the top underway causal factors (Figure 2.5), judgment was consistently cited as the

highest percentage each year and continued to be the leading causal factor reported in operational

cutter mishaps. Fatigue shows up as one of the top five causal factors for Underway/Operational

mishaps but it was not amongst the top five inport mishaps. Judgment, experience and planning

are personnel factors. Operational risk management can be applied to identify these latent unsafe

decisions before they manifest into mishaps.

0

20

40

60

80

100

2005

[107]

2006

[139]

2007

[142]

2008

[152]

2009

[128]

2010

[104]

2011

[131]

2012

[137]

2013

[106]

2014

[118]

2015

[113]

Number of Causal Factors

Judgment

Experience

Weather

Planning

Fatigue

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 16 of 72

Inport Mishaps

Figure 2.6: FY15 Type/Number of Cutter Injuries (Inport)

FY05-FY14 Average

Standard Deviation

FY15

Inport Mishaps

177

31.5

252

Inport Injuries

106

20.3

106

Inport Lost Work Days

451

152.4

347

Table 2.3: FY15 Cutter Crew Mishaps/Injuries Compared to FY05 - FY14 (Inport)

Analysis of Inport Injuries

Analysis of inport injuries revealed that most occurred during maintenance and repair activities.

In FY15, there were 106 injuries inport (figure 2.6), and cuts accounted for 23% (24/106). The

majorities of cuts were obtained while transiting ladders, catching body parts in QAWTD’s, and

the use of box cutters and knifes while opening packages/supplies. Bruises accounted for 16%

(16/106) of injuries and were due to slips trips and falls and while working on cutter equipment.

Fractures accounted for 11% (12/106) of injuries. Major causes of fractures were working on and

inspecting hatches and QAWTD’s slips, trips, and falls. Other notable injuries include irritation

of the eye caused by improper use of eye protection when performing the duties of fire watch,

working with small power tools, and handling chemicals.

3

1

16

3

6

24

7

12

2

7

2

11

10

2

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Number of Injuries (Inport)

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 17 of 72

Figure 2.7: Top Five Causal Factors: FY05-FY15 (Inport)

Numbers in brackets depict number of mishaps (per year). Each reported mishap can have multiple causal

factors.

Similar to the Underway/Operational causal factors, judgment was consistently cited as the highest

percentage inport causal factor each year (figure 2.7) and continued to be the leading causal

factor reported. Judgment, experience, planning and management are personnel factors. Sports

causal factors are marked when a mishap occurs during command sponsored sporting events.

Although not shown, leading non-personal factors were engineering design and failure

(equipment/system) for both underway and inport.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

2005

[205]

2006

[155]

2007

[129]

2008

[152]

2009

[187]

2010

[129]

2011

[192]

2012

[200]

2013

[218]

2014

[207]

2015

[252]

Number of Inport Causal Factors

Judgment

Experience

Sports

Planning

Management

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Cutter Operational Mishaps Page 18 of 72

CG Cutter Top Ten Hazardous Conditions

Checklist Number

Checklist Item

ES-52

Electrical Safety; All electrical equipment shall be free from recognized

hazards that are likely to cause death or serious physical harm.

FS-54

Fire Safety; Flammable lockers are in good condition and doors are self-

closing and latch upon closure. A current inventory of the contents is

posted on the door of the cabinet.

ENG-05

Engineering; Guards are installed on all rotating machinery, including

couplings and exposed shafts, to prevent personnel from becoming

accidentally entangled or injured.

FS-55

Fire Safety; Compressed gas bottles are stored in an upright position

with individual steel collars.

ES-57

Electrical Safety; Transient voltage surge suppressors (computer power

strips) are to be mounted in a way that allows them to be removed

without the use of tools; cannot be series connected to one another

(daisy chained); and are not used in conjunction with extension cords.

ES-16

Electrical Safety; During normal operations, all fuse boxes, junction

boxes, switch boxes, electrical enclosures, and wiring accessories shall

be kept closed (with provided covers) and properly secured.

HC-11

Hazard Communication Program; Secondary containers for hazardous

materials are labeled, marked with name of materials as indicated on

the SDS, principal hazard, effects of overexposure, and name and

number of manufacturer or supplier.

HAB-02

Habitability; There are no food items in non-messing areas.

LLRD-06

Ladder Safety ; Three slip-resistant self-adhesive treads with no space

between them are installed at the head and foot of ladders, on each

side of doors used for continuous traffic, and at both sides of doors in

crews messing.

PPE-10

Personal Protective Equipment; Eyewash units are inspected and

maintained in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. Plumbed

equipment shall be activated weekly to verify proper operation.

Table 2.4: Cutter Safety Assessment Analysis - Top Ten Hazardous Conditions

Notifications (HCN’s) Recorded During FY15 Cutter Safety Assessments

Table 2.4 summarizes the top cutter SEH deficiencies, excluding administrative and training

items, identified during FY15 SMART visits and Ship Sanitation Certificate Program inspections

(formerly de-rats). Electrical discrepancies were the most cited discrepancies.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Boat Operational Mishaps Page 19 of 72

Boat Operations

Key Takeaways

In FY15, most boat injuries occured at the pier; the most frequent injury was irritation

or a foreign object in CG member’s eyes.

Slips/trips and falls at the pier while transfering on and off the boat and between

platforms underway was the second largest cause on injury. This also attributed to the

increase to PIW’s (person-in-water).

Laser strikes to boat crew members doubled from the previous year.

There was a decrese in groundings, which predomintly occurred while at low speed

(clutch to around 3-5 knots).

Boat Unit Mishaps

Figure 3.1: FY15 Mishaps by Boat Type

1

11

5

42

22

63

67

2

1

20

9

16

6

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Number of Mishaps

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Boat Operational Mishaps Page 20 of 72

Figure 3.2: FY15 Boat Mishaps by Mission Type.

Figure 3.1 and 3.2 show frequency counts of mishaps by boat type and mishaps by mission respectively

and does not account for operational hours (i.e., operational hours were not consistently available for

individual boat types or by missions in CGBI to normalize the

data to a rate). This limits comparisons across platforms and

missions.

As shown in Figure 3.1, the RB-M and RB-S II account for

49% of all boats mishaps reported in FY15. Analysis and

review of the reported mishaps across “Boat Types” and

“Mission Types” identified commonalities of mishap types

while in performance of CG missions. Figures 3.1 and 3.2

used the same mishap data set.

Mishap Summary

Analysis of boat unit mishaps revealed boat crews were exposed to “green” lasers while

patrolling and maintaining security zones during large public events. Several boat crew members

were injured (cuts, contusions, sprains, back pain) during aggressive maneuvering (hook-a-

chine), or coming off the back of a wave/swell. PIW’s (Person-In-Water) occurred: at the pier –

embarking, disembarking, mooring, and untying boats; during training missions - retrieving

OSCAR, or throwing the heaving line; hooking-a-chine; and law enforcement operations –

transferring between vessels.

23

3

3

32

14

1

1

23

14

43

108

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

ATON

C&S

DO

ELT

M+R

MER

MI

OTHER

PSS

SAR

TRG

Number of Mishaps

Mission

Description

ATON

Shore and Radio Navigation Aids

C&S

Command and/or Support

DO

Defense Operations

ELT

Enforcement of Laws and Treaties

OTHER

Other Not Listed

M+R

Maintenance and Repair

MER

Marine Environmental Response

MI

Marine Inspection

PSS

Port Safety and Security

SAR

Search and Rescue

TRG

Training

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Boat Operational Mishaps Page 21 of 72

Figure 3.3: FY05 – FY15 Top Five Types of Boat Unit Mishaps.

Figure 3.3 shows the FY15 top five most frequently reported operational mishaps. For the

purpose of comparison, data for the FY15 top five mishaps are also shown retroactively from

FY05 through FY14. Table 3.1 below presents averages and standard deviations calculated from

FY05 through FY14 as well as total mishap reports for FY15.

The top five types of mishaps accounted for 35% (219/634) of the total. The number of

groundings showed a decreasing trend from FY13 through FY15. However, it was the most

frequently cited type of mishap in FY15 with a total damage cost of $75K (10% of total boat

unit’s damage costs). Groundings accounted for 30% (65/219) occurring while transiting shallow

water near channels and jetties, assisting vessels in distress, and while performing CG operations

such as ATON, ELT and SAR. Analysis of the groundings showed many occurred during

training of crew members while conducting area familiarization. The majority of groundings

occurred under “slow” speed (clutch ahead to 2-3 knots), where there was minimal to no damage

to the boat. Similarly, collisions between boat-to-boat, boat-to-pier, bridges, and locks occurred

at “slow” speed. Conversely, striking-a-submerged object occurred at “speed” and without

warning.

Laser mishap tracking began in FY13 and the numbers of reported laser mishaps were almost the

same in FY13 and FY14. However, there was a significant increase (121%) in FY15 compared

to FY14 (Figure 3.3).

Trailering mishaps, as shown in table 3.1, were reduced in FY15 significantly when compared to

the 10-year average (>2 standard deviations). Trailering persistently is the cause of mishaps with

the striking of overhead objects, garage doors, trees, low overhangs, and bridges while being

towed. In one mishap, the unit had spotters port and starboard, bow and stern – but nobody

looked UP! The boat was trailered and returning to the unit with the radar and antenna(s) in the

upright position.

86

108

100

87

70

71

83

68

92

73

65

64

67

66

90

82

112

66

48

49

54

51

49

37

50

40

41

41

38

48

44

34

43

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

13

14

31

41

60

62

59

66

62

48

53

47

30

29

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Number of Mishaps

Types of Mishaps - Top 5

Grounding

Slip Trip Fall

PIW

Laser

Trailering

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Boat Operational Mishaps Page 22 of 72

FY05-FY14 Average of Type

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Types – Top 5

Grounding

84

13

65

Slip Trip Fall

70

19

51

PIW

42

5

43

Laser

3

5

31

Trailering

53

11

29

Table 3.1: Top Boat Mishaps Type FY15 compared to FY05-FY14 10-year average.

Note: Operational mishaps include underway mishaps only (steaming, anchoring, mooring, etc.).

Figure 3.4: Boat Underway Injury Rates, FY05-FY15

Underway Injury rates increased in FY15 to 5.1 from 4.4 in FY14. Table 3.2 shows in FY15 boat crew

members were injured more often inport (158) than underway (22). During our analysis of the

underway injuries, 41% (9/22) occurred during ELT operations on RB-S II and Defender Class

A&B boats, 23% (5/22) occurred during SAR operations onboard RB-S II, MLB-47 and SPC

(SW) boats, and 18% (4/22) occurred during waterway management operations aboard RB-S II

boats. Other operations where injuries occurred were noted during ATON and PSS.

10-Year Average of Total

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15

Mishaps – Total

798

83

634

Injuries

169

15

158

Underway Injuries

35

13

22

Lost Time Cases

73

13

60

Lost Days

513

106

319

Property Costs (Millions)

$1.24

$0.31

$0.78

Table 3.2: Boat Unit Mishap Summary FY15 compared to FY05-FY14 10-year average

7.3

8.9

8.4

11.1

7.6

9.4

5.6

4.2

4.7

4.4

5.1

-

2

4

6

8

10

12

-

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

600,000

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Injuries Per 100K Resource Hours

Small Boat Op Hours

Boat OP Hours

Underway Injury Rate

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Boat Operational Mishaps Page 23 of 72

Analysis of Injuries

Small Boat Units (SBU’s) encompassing STAs, ANTs, MSSTs and

MSRTs reported a total of 158 injuries in FY15 (see table insert:

FY15 Boat Unit “Injury Type”). Slips/Trips/Falls were the most

frequent cause of injury, 30% (47/158). Irritation, foreign objects in

member’s eyes, (lasers, gasoline, and paint) accounted for 15%

(21/158) of the injuries.

Lacerations/Cuts - 15% (24/158) were inflicted by cutting

instruments (i.e. knives or razor blades); most commonly while

opening packages, cutting line, or preparing food. Lacerations /Cuts

also occur when member’s fall encountering heavy seas in boats,

cuts to the head or extremities from knife edges on hatches or doors.

These can be prevented by using snips or safety blades when

appropriate, and keeping a hand free when transiting through the

boat.

Recent changes to the Occupational Medical Surveillance and Evaluation Program (OMSEP)

requires personnel who are exposed to noise levels above the threshold limit value for a single

exposure vice a 30-day exposure are required to be enrolled in OMSEP. Coordinate enrollment

by contacting your local Safety and Environmental Health Officer (SEHO); for a listing, see

resources page located in the SEH Resources section.

Laser strikes, predominantly green lasers, striking boat crews from other small craft or from

shore accounted for 20% (31/158) of total mishaps. Out of the thirty-one mishaps, seven led to

eye irritation of boat crew.

Fractures accounted for 16% (25/158) of injuries. Six of the mishaps occurred while conducting

maintenance and repair; the remainder occurred during training, SAR, and ATON evolutions.

Of the injuries, sprains accounted for 13% (20/158) for boat units occurred underway and most

were from heavy seas, and members tripping, falling or stepping over equipment.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

2005

[805]

2006

[894]

2007

[886]

2008

[891]

2009

[827]

2010

[790]

2011

[713]

2012

[738]

2013

[809]

2014

[623]

2015

[634]

Number of Causal Factors

Judgment

Experience

Planning

Weather

Communication

Y15 Boat Unit “ Injury Type”

FRACTURE

25

CUT

24

IRRITATION

21

SPRAIN

20

STRAIN

14

ABRASION

10

BRUISE

8

DISLOCATION

5

ELECTRICAL SHOCK

5

BURN

4

CONCUSSION

4

PUNCTURE

3

AMPUTATION

1

LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

1

OTHER

13

Note: On Duty CG Only

Motor Vehicle Mishaps not Included.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Boat Operational Mishaps Page 24 of 72

Figure 3.5: Top Five Causal Factors, FY05-FY15

Numbers in brackets depict the number of mishaps (per year). Multiple causal factors are routinely

identified by reporting units.

FY05-FY14 Average of Type

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Types

Judgment

386

48

294

Experience

227

32

194

Planning

191

32

127

Weather

151

27

111

Communication

120

20

94

Table 3.3: FY15 Boat Operational Mishap Causal Factors

Four of the top five causal factors fall under the personal factors category shown in Table 3.3.

Similar to the operational cutter causal factors, judgment was consistently cited as the highest

percentage causal factor each year (figure 3.5) and continued to be the leading causal factor

reported. Judgment, experience, planning and communication are personnel factors. Although

not shown, leading non-personal factors were engineering design and failure

(equipment/system).

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Shore Mishaps Page 25 of 72

Shore Operations

Key Takeaways

Slips/Trips/Falls are consistently the leading type of mishap and accounted for over

60% of the FY05-FY15 period.

Cuts/Lacerations were the most commonly reported occupational injury; the most

frequent was from the use of knives.

The most often cited hazardous condition notifications are related to electrical system

conditions, egress & exiting procedures (EAP), and the lack of hearing conservation

training and documentation.

FY15 reported a total 649 mishap; of these, 144 were associated with injuries, and 92

resulted in property damage mishaps. The remaining 413 mishaps are associated with

HIPOs and mandatory reporting.

On and Off-Duty Mishaps (The mishaps in this chapter do not include Boat STAs. Shore

facilities include Bases, TRACENs, Boat Maintenance Facilities and Shops, Major Industrial

Units, Non–Industrial Units, and CG-occupied office spaces.)

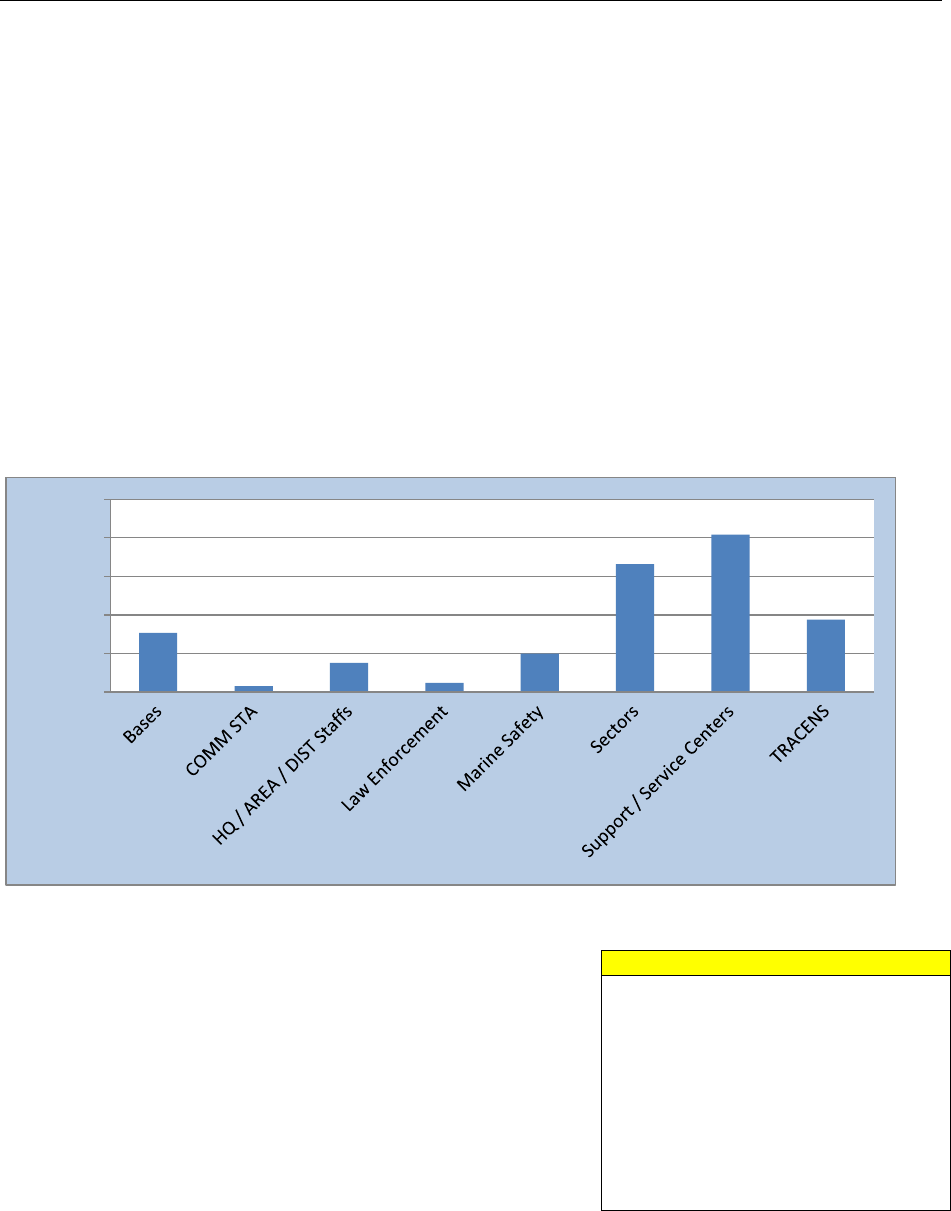

Figure 4.1: Mishaps by Major Shore Unit Types (On and Off Duty)

Off-duty mishaps are included in the figures above and

discussed in detail in a separate chapter. They are briefly

mentioned in this section to emphasize the impact they have

on operational missions. CG members’ individual

operational readiness is impacted when they experience an

off duty injuy resultining in hospitalized, lost, and restricted

work days. This has an overall effect on command

readiness and capabilities.

Motor vehicle, motorcycle, ATV, and off-road dirt bike

mishaps are also included in the above figures and further

analyzed in a later chaper.

77

8

38

12

50

166

204

94

0

50

100

150

200

250

Number of Mishaps

Mission

Description

ATON

Shore Navigation Aids

C&S

Command and/or Support

ELT

Enforcement of Laws and Treaties

OTHER

Other Not Listed

M+R

Maintenance and Repair

MER

Marine Environmental Response

MI

Marine Inspection

PERS

Off Duty/Off-The-Job

PSS

Port Safety and Security

TRG

Training

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Shore Mishaps Page 26 of 72

Figure 4.2: Shore Mishaps by Mission Type

Figure 4.3: Shore Personnel Injury and Lost Time Case Rates

FY05-FY14 Average

Standard Deviation

FY15

Total Mishaps

654

36

649

Injuries

142

16

144

Lost Time Cases

72

11

59

Lost Days

432

90

499

Property Cost

$0.76

$0.42

$0.48

Table 4.1: Shore Injuries, Mishaps, and Property Cost 10-Year Average vs. FY15

Yearly costs are not adjusted for inflation. This cost does not include property cost associated with Boat

Units (STAs, MSSTs, ANTs, and PSUs).

Over the past ten years, total shore mishaps averaged 654 mishaps per year with a standard

deviation of 36 mishaps. The number of shore reported mishaps remained consistent in FY15

when compared with the 10-year average. In the same period, mishap related property damage

decreased by $30,000 compared to the average.

4

93

3

157

6

18

17

260

2

89

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

ATON

C&S

ELT

M+R

MER

MI

OTHER

PERS

PSS

TRG

Number of Mishaps

0.00

0.10

0.20

0.30

0.40

0.50

0.60

0.70

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Injury and Lost Time Rate

per 100 people

Injury Incident Rate

Lost Time Case Rate

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Shore Mishaps Page 27 of 72

Analysis of FY15 Injuries

Cuts/Lacerations were the most commonly reported occupational injury, 24%

(27/144) occurring during normal working conditions as a result of a slip, trip

or fall, performing buoy maintenance, moving equipment utilizing a knife

while performing food preparation and the opening of boxes and packages.

Fractures were 12% (14/144) of shore facility injuries occurring during

sponsored training exercises (boarding member training, use-of-force

classes), slips, trips, and falls, the unintentional closing of doors and hatches,

and loading/unloading of material and equipment.

Inhalation precipitating an occupational or acute exposure occurred 10% (12/144) when

members inhaled ammonia vapors escaping from manifold valves while performing inspection,

contacting asbestos, and performing an oil facility safety examination and hydrogen sulfide was

detected by a member’s personally worn gas meter.

CG members received concussions during “Incentive Training” - passing out and striking their

head on the ground, during training (self defense, REDMAN) from blows to the head, and from

slips or falls on ice.

Figure 4.4: FY05 – FY15 Shore Mishaps by Type

97

118

109

131

129

148

95

79

90

109

91

37

42

36

35

33

29

23

17

25

21

23

12

7

9

8

17

15

6

9

17

7

10

13

8

6

7

2

10

9

11

6

7

8

10

10

7

8

9

8

8

8

7

4

8

0

50

100

150

200

250

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Number of Mishaps

Types of Shore Mishaps (10 years)

Slip Trip Fall

Lifting

Fire

PIW

Trailering

FY15 Shore Injuries

CUT

27

FRACTURE

14

INHALATION

12

STRAIN

8

BRUISE

7

CONCUSSION

7

SPRAIN

6

ABRASION

6

BURN

6

IRRITATION

4

OTHER

9

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Shore Mishaps Page 28 of 72

FY05-FY14 Average of Type

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Types

Slip Trip Fall

111

20

91

Lifting

30

8

23

Fire

11

4

10

PIW

8

3

8

Trailering

8

2

8

Table 4.2: Top Shore Mishaps by Type, FY15 compared to FY05-FY14 10-year average

From FY05 to FY15, “slips, trips, and falls” is clearly identified as the leading mishap type.

Lighting, wet and slippery surfaces (walking and working surfaces), moving surfaces, blocked

and obstructed aisles and walkways, ladders, unguarded openings, and elevated work surfaces

are all contributing factors. Rushing, inattention, and distractions also contribute to falls.

Figure 4.5: Top Five Major Shore Causal Factors, FY05-FY15

FY05-FY14 Average of Type

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Causal Factors

Judgment

283

31

243

Planning

119

16

130

Experience

96

17

90

Weather

48

10

54

Fatigue

36

5

53

Table 4.3: Top Five Major Causal Factors FY15 compared to FY05-FY14 10-year average

In looking at the top shore causal factors (Figure 4.5), judgment was consistently cited as the

highest percentage each year and continued to be the leading causal factor reported in shore

mishaps. Judgment, planning, and experience are personnel factors and Operational Risk

Management (ORM) can be applied to identify these latent unsafe decisions before they manifest

into mishaps.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

2005

[685]

2006

[677]

2007

[675]

2008

[699]

2009

[683]

2010

[657]

2011

[615]

2012

[584]

2013

[654]

2014

[611]

2015

[649]

Number of Causal Factors

Judgment

Planning

Experience

Weather

Fatigue

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Shore Mishaps Page 29 of 72

Checklist Number

Checklist Item

EAP-08

The FEAP provides training so that personnel are familiar with the

provisions of the Facility's Emergency Action Plan.

EGR-07

All parts of the fire protection and life safety systems (e.g.,

automatic sprinklers, alarms, exit lighting, fire doors) are

maintained in proper operating condition.

EE-02

Circuit breakers in electrical distribution panels are labeled.

HCP-02

All personnel exposed to hazardous noise receive initial

(minimum of 1 hour) and appropriate annual refresher training in

hearing conservation practices. Training is documented in TMT.

EE-05

All outlet boxes, junction boxes, and fittings are provided with

covers.

EE-10

Flexible cords and cables are prohibited:

HABB-16

Reports of visible mold, biological growth, and moisture

intrusion/condensation indoors are promptly investigated,

sources of moisture are identified and eliminated, and all

affected building materials/contents are cleaned to mitigate and

prevent Indoor Air Quality problems.

EE-04

A 36-inch emergency access area is maintained in front of all

electrical distribution panels with voltages of 600 volts or less.

Note: This space may not be used for storage of any kind and

must remain open and clear at all times.

LOTO-10

The unit trains all personnel to ensure that the elements of the

Lockout Program are understood. Training is documented in

TMT.

FE-01

Fire extinguishers are present and visually inspected monthly.

Table 4.4: FY15 Shore, Safety Mobility, Assistance, Response and Training Visit

(SMART) - Top Ten Hazardous Conditions Notifications (HCN’s) identified during FY15 SMART

visits.

Electrical discrepancies are cited as the top material issues encompassing wiring, power strips,

extension cords, exposed electrical parts, missing GFCI’s, lack of panel clearance, and unlabeled

circuit breakers.

Fire and life safety issues included lack of emergency action plans, lack of general fire protection

system maintenance, and lack of exit signs.

Another common issue is the lack of hearing conservation training and documentation. Members

are encouraged to review COMDTINST M5100.47A, Chapter 10 B.3.f. OMSEP reports noise

(hearing) testing for individuals are currently at 48% in compliance Coast Guard-wide.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Deployable Special Forces Page 30 of 72

Deployable Special Forces (DSF) Operations

Key Takeaways

In FY15 there were a total of 96 mishaps in the DSF community. Of the total mishaps,

38 (40%) occurred during training missions.

There was a total of 71 injuries during FY15. Forty-two injuries occurred while on

duty. Of the 42 on-duty injuries, 34 happened during training evolutions.

Due to the nature of the high risk evolutions performed in this community, continuous training

operations, and the physical demands placed on the operators, our mishap prevention efforts call

for nonstop emphasis both on- and off-duty.

Figure 5.1: FY15 DSF Mishaps by Mission.

As referenced in figure 5.1, there were a total of 96 mishaps in the DSF community in FY15. Of

the total mishaps, 40% (38/96) occurred during training missions; 31% (30/96) during off-duty,

and 11% (7/96) during C&S operations.

Figure 5.2: Top Five Types of DSF Mishaps, FY05-FY15

The top five mishaps types were identified in FY15 and these are compared to the same types of

mishaps from previous years (figure 5.2).

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Deployable Special Forces Page 31 of 72

The DSF community experienced a decrease in Trailering, PIWs and Unintentional Firearm

Discharge mishaps in FY15. Grounding and Allision was at the same level or had a slight

increase in the performance of boat operations.

FY05-FY14 Average of Type

Mishaps

Standard Deviation

FY15 Types

Grounding

6

4

6

Trailering

8

3

4

PIW

6

3

1

Allision

1

1

3

Firearm

3

2

2

Table 5.1: Top Five DSF Mishaps by Type , FY15 compared to FY05-FY14 10-year average

ON DUTY

OFF DUTY

Reported Injuries

42

28

Lost Work Days

62

304

Hospital days

2

14

Restricted Days

483

1214

Table 5.2: DSF FY15 Injuries with Lost Work

Analysis of Injuries

In FY15, there were a total of 70 injuries, 30 of which incurred lost work days. Fifty-nine percent

(42/70) of injuries occurred while members were in on-duty status and 40% (28/70) were off-

duty and off-the-job.

Of the on-duty injuries, 81% (34/70) took place during training evolutions; specific areas of

concern are: unit sponsored physical fitness, defense tactics (hand-to-hand), water survival

training, hook and climb, fast rope, and obstacle courses.

The DSF community experienced one class B mishap with “partial disability,” resulting in a

fractured back while role playing during Tactical Sustainment Training (TST) in a use-of-force

scenario.

Each mishap impacted our ability to some degree to support specialized mission capabilities and

deployment readiness. There were 30 lost work cases reported. Off-duty mishaps were

accountable for 83% (304/366) lost work days, 88% (14/16) hospital days, and 72% (1214/1697)

restricted days. Property damage mishaps resulted in $171K in repairs or replacement.

For more information on DSF specific mishaps, contact HSWL SC (se) at (757) 628-4392.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Marine Environmental Response and Marine Inspection Page 32 of 72

Marine Environmental Response and Marine Inspection

In FY15, there were a total of 28 mishaps of which 25 mishaps involved injuries related to

Marine Inspections and Marine Environmental Response efforts accounting for 29 lost work

days, 3 hospital days, and 108 restricted days.

Ten of the injuries involved inhalation, and four involved cuts/lacerations by CG inspectors. In

the most severe cases of exposure, four inspectors entered unknowingly into a facility that was

contaminated with asbestos while investigating the source of oil discharging into the water.

Members were exposed for approximately 20 minutes and disturbed little if none of the asbestos.

In another incident, three inspectors noticed their gas meter had registered exposure to hydrogen

sulfide while conducting a security exam of a bulk oil facility. Minor dizziness was noted and

subsided after members left the site.

In one incident, while the member was conducting an inspection of a small passenger vessel, the

member injured their back when the member fell into an open hatch. The member was

hospitalized for two days. Another member was hospitalized for one day while conducting an

internal structural examination of a freight barge, due to the difficult design of the vessel’s

internal structures.

Vessel examinations during construction or extensive alterations, particularly those by marine

inspectors on barges are inherently dangerous. The need for the inspector to climb to inspect

areas that are not accessible increases the hazard of the job. Units should review local policies

and procedures to ensure proper safeguards are present during marine inspection activities of this

nature.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Off-Duty and Recreational Mishaps Page 33 of 72

Recreational and Off Duty Mishaps

Key Takeaways

Sports are the highest contributors to off-duty mishaps.

Off-duty sports/fitness activities accounted for 360 injuries in FY15, while 72 sports

injuries were on-duty (command fitness activity).

Basketball injuries accounted for 279 lost work days and 1,962 restricted days.

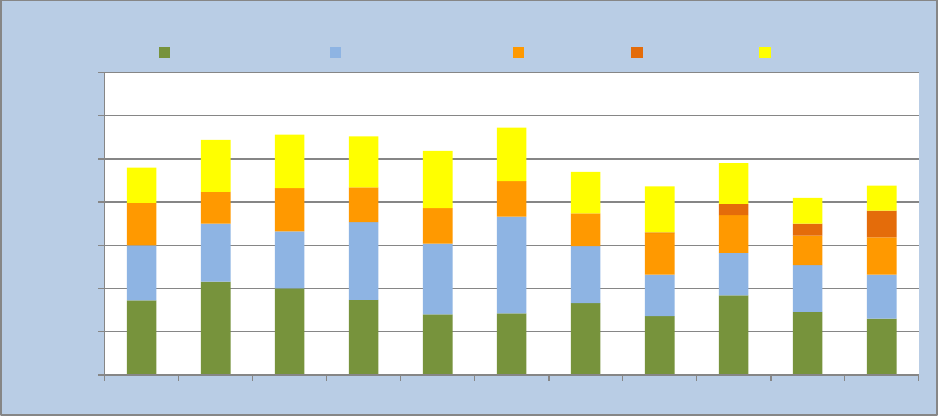

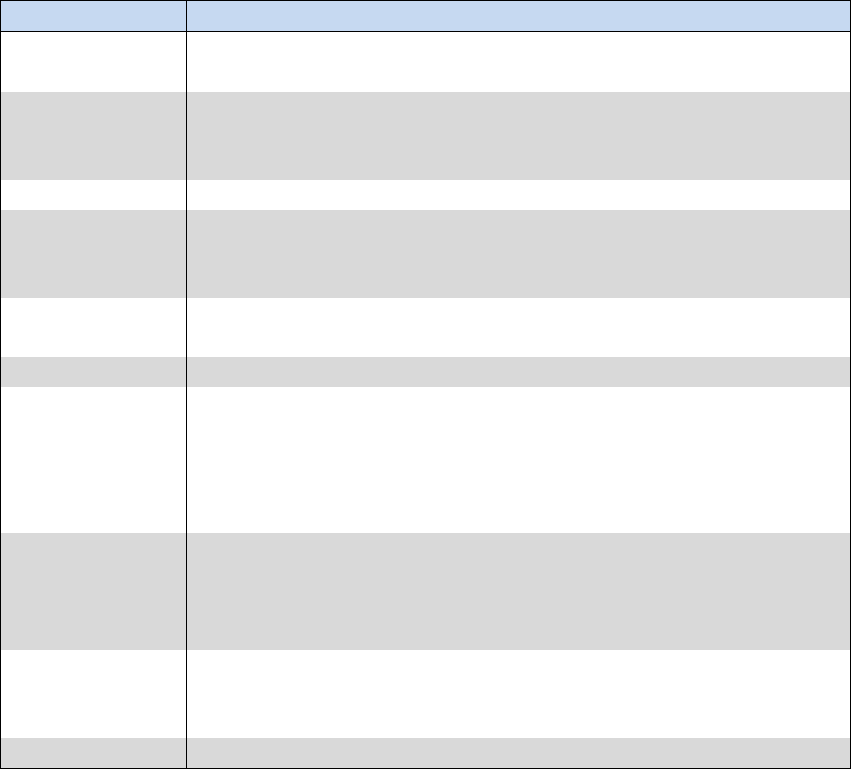

Figure 6.1: FY15 Days Lost Due to Injury (hospitalized and restricted)

There were more off-duty mishaps as a whole and accounted for the majority of the injuries,

hospitalizations, lost workdays, and days restricted. Our goal is to eliminate unsafe acts, reduce

mishaps, and eliminate risky behavior—anything less is unacceptable.

In December 2014 (FY15 Q1), a group of members were crossing a highway in the early

morning hours during a time of low-lying fog. The last member to cross was struck by a van and

later died of the injuries incurred.

Off-Duty

FY05- FY14

Average

Standard

Deviation

FY15

Cutter Injuries

167

14

119

Cutter Lost Time Cases

124

14

83

Cutter Lost Days

1780

395

1338

SBU Injuries

178

20

162

SBU Off-Duty Lost Time Cases

116

12

93

SBU Lost Days

1301

212

1021

Aviation/Av Support Injuries

71

12

66

Aviation/Av Support Lost Time Cases

50

11

34

Aviation/Av Support Lost Time Cases

534

230

370

Shore Injuries

224

21

260

Shore Lost Time Cases

170

18

187

Shore Lost Days

1580

271

1847

Table 6.1: Summary of Off-Duty Injuries, Lost Time Cases, and Lost Days

Note: off-duty only accounts for military personnel.

629

319

126

499

1338

1024

370

1844

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

1800

2000

Cutter Crews

Small Boat Units

Aviation Support

Shore

Days Lost

On Duty

Off Duty

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Off-Duty and Recreational Mishaps Page 34 of 72

Sports are the highest contributors to off-duty mishaps. Many injuries are severe, with significant

lost work days which ultimately impact the readiness of the unit. For instance, basketball

accounted for 279 lost work days and 1,962 restricted days. Football was responsible for 317 lost

work days and 1025 restricted days. Over the past 10 years, injuries attributed to on-duty sports

activities averaged 65 injuries per year, while off-duty sports related injuries averaged 262 per

year. In FY15, there were 72 on-duty sports injuries and 276 off-duty sports injuries.

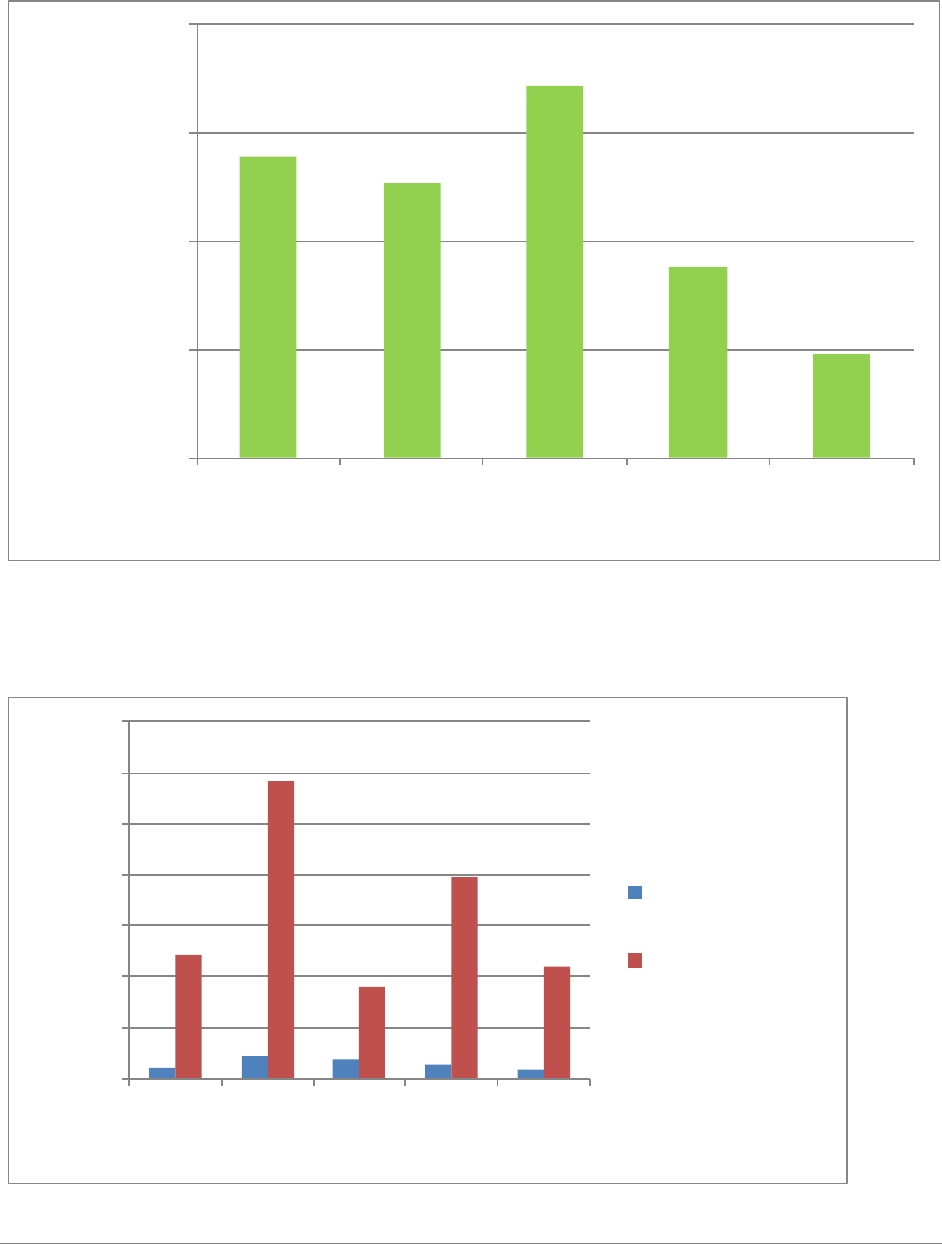

Figure 6.2: Top Twelve Sports or Fitness Activities Implicated in FY15 Injury Mishaps

Analysis of the basketball mishaps indicated that ankle injuries are the leading type with the

highest incidents occurring during the winter months.

Snowboarding continues to be the leading cause of snow sports mishaps, accounting for 18 out

of 21 injuries. Mishap reports indicated helmets were worn in most instances and these injuries

were mainly wrist and shoulder related. Off-highway vehicle (dirt bikes and ATVs) mishaps

declined significantly again this fiscal year. Over the 10 year period, off-highway related injuries

averaged 34 events per year, with only 12 being reported during FY15.

As with afloat and shore on-duty mishaps, personal factors are the leading causal classification

for off-duty injuries. This emphasizes the importance of the human element in risk mitigation

and hazard avoidance.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Off-Duty and Recreational Mishaps Page 35 of 72

Motor Vehicle Mishaps

Key Takeaways

About 50% of motor vehicle mishaps over the last 10 years involved motorcycles.

In FY15, no motorcycle mishaps resulted in fatalities. Most members involved in

motorcycle accidents had received at least the minimum motorcycle training required.

Figure 7.1: Class A Fatal Motor Vehicle Mishaps Passenger Vehicles and Motorcycles

Off-duty motor vehicle mishaps typically lead the list of causes for CG fatalities each year.

During FY15, two members were lost in fatal vehicular crashes. For the first time in over 10

years, there were no fatalities caused while riding motorcycles. However, there were 52

mishaps involving motorcycles, mopeds and ATVs during FY15 which resulted in 855 lost work

days, 157 hospital days, and 1123 restricted days. These numbers are significant in that, on

average, each mishap resulted in approximately 11 lost work days.

Most motorcyclists had received at least the minimum required motorcycle safety training. The

Coast Guard provides support in obtaining either local Coast Guard or DOD training or

reimburses the member for commercial training.

The latest National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) published data found that,

“per mile traveled, motorcyclists were more than 26 times more likely than passenger car

occupants to die in a traffic crash.” The most straightforward risk management strategy to

significantly increase the chances of surviving a motor vehicle crash is to drive a modern car or

truck, wear seatbelts all the time, and drive responsibly.

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Laser Illumination Mishaps Page 36 of 72

Laser Illumination Mishaps

Key Takeaways

The number of laser illumination incidents continues to rise. One possible solution -

coordinate with local municipalties and authorities to discourage the sale of handheld

lasers in high tourism areas.

Eye irritation (flash blinding) is the most prevalent injury when a laser illumination

occurs.

Figure 8.1: FY05 – FY15 Laser Illuminations (Non-Aviation)

The number of laser devices is proliferating and can pose a threat to the eye, both temporarily

and permanently. The frequency of laser exposures is likely to continue rising as evidenced over

the past few years. A sharp increase in the number of laser exposure events is reflected in Figure

8.1, indicating a significant increase in vessels and boats. Laser events for non-aviation units

have only been tracked in the mishap database starting FY13.

As laser strikes initiated from shore and other small craft continues to rise, it causes concern for

members. Laser exposures can have a wide range of effects including flash blindness, dazzle,

dark spots, hazy vision, floaters, burns, retinal bleeding, etc. Of special interest are the hazards

posed by visible lasers from glare and flash blindness.

All personnel who report being lased must seek medical evaluation. If an optometrist or

ophthalmologist confirms an acute laser overexposure incident, report the laser incident to the

immediate operational chain of command and the Tri-Service LASER Injury Hotline at 800-473-

3549.

Additional laser policy, guidance and reporting procedures are provided in the following

references:

Safety and Environmental Health Manual, COMDTINST M5100.47 (series), Chapter 3

Mishap Response; Chapter 23 Non-Ionizing Radiation Program.

ALCOAST 251/13: ASSET SPECIFIC LASER INCIDENT GUIDANCE

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

7

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

13

14

31

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Number of Laser Incidents

Cutter Laser Incidents

Shore Laser Incidents

Small Boat Incidents

USCG HSWL Service Center Annual Safety Report FY15

Environmental & Occupational Illness Mishaps Page 37 of 72

Environmental & Occupational Illness Mishaps

BACKGROUND: