EN EN

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Brussels, 10.10.2023

SWD(2023) 670 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

EVALUATION

of Commission Regulation (EC) N° 906/2009 of 28 September 2009 on the application of

Article 81(3) of the Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and concerted

practices between liner shipping companies (consortia)

{SWD(2023) 671 final}

1

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 3

1.1. Purpose of the evaluation ..................................................................................... 4

1.2. Scope of the evaluation ........................................................................................ 8

2. WHAT WAS THE EXPECTED OUTCOME OF THE INTERVENTION? ........... 10

2.1. Description of the intervention .......................................................................... 10

2.2. Description of the objectives of the intervention ............................................... 11

2.3. Points of comparison ......................................................................................... 17

3. HOW HAS THE SITUATION EVOLVED OVER THE EVALUATION

PERIOD? ................................................................................................................... 18

3.1. State of play in 2019 .......................................................................................... 18

3.2. Current state of play ........................................................................................... 18

4. EVALUATION FINDINGS (ANALYTICAL PART) ............................................. 27

4.1. TO WHAT EXTENT WAS THE INTERVENTION SUCCESSFUL AND

WHY? ........................................................................................................................ 27

4.1.1. Legal certainty ................................................................................................... 27

4.1.2. Administrative supervision ................................................................................ 33

4.1.3. Coherence .......................................................................................................... 33

4.1.4. Facilitation of pro-competitive consortia ........................................................... 35

4.1.5. Conclusion ......................................................................................................... 36

4.2. HOW DID THE EU INTERVENTION MAKE A DIFFERENCE AND TO

WHOM? .................................................................................................................... 37

4.3. IS THE INTERVENTION STILL RELEVANT? .................................................... 39

4.3.1. Efficiencies and consumer benefits brought by consortia ................................. 39

4.3.2. Consortia’s contribution to EU competitiveness and trade ............................... 55

5. WHAT ARE THE CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED? ....................... 57

5.1. CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................................... 57

5.2. LESSONS LEARNED .............................................................................................. 59

ANNEX I: PROCEDURAL INFORMATION ............................................................... 61

ANNEX II. METHODOLOGY AND ANALYTICAL MODELS USED ....................... 63

ANNEX III. EVALUATION MATRIX ........................................................................... 66

ANNEX IV. OVERVIEW OF BENEFITS AND COSTS ................................................ 70

ANNEX V. STAKEHOLDERS CONSULTATION - SYNOPSIS REPORT ................. 72

2

Glossary

Term or acronym

Meaning or definition

CBER

Consortia Block Exemption Regulation

Commission

European Commission

Council

European Council

EEA

European Economic Area (27 EU Member States and

Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, the three EEA

EFTA States)

EFTA

European Free Trade Association

EU

European Union

SME

Small and medium-sized enterprise

SWD

Staff Working Document

TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

3

1. INTRODUCTION

Liner shipping is the provision of regular, scheduled, maritime freight transport, mainly

by container, between ports on a particular route, generally known as a trade. The

dramatic supply chain crisis that followed the COVID-19 outbreak has highlighted the

leading role played by the sector in trade and globalisation. In 2020, about 70% of the

value of international trade was carried by maritime transport, of which about two-thirds

was carried by containers.

1

In the 1980s, the Commission undertook to assess the implications for EU competition

policies of the organisational changes undergone by world shipping.

2

Those changes

consisted notably in the development of containerisation,

3

which prompted individual

shipping lines (“carriers”) to use larger ships to minimise costs, increased the capital

investment needed to establish a regular service and reduced the ability to transfer

capacity from one trade to another, thus putting pressure on certain carriers to cooperate

with each other. A common form of cooperation between carriers was joint service

agreements, also referred to as consortia.

The Commission found that it was desirable that consortia benefit, as far as possible,

from a group exemption from the EU antitrust rules prohibiting agreements that restrict

competition. While consortia might reduce or eliminate competition between their

members with regard to e.g. the provision and use of capacity and determination of

timings and sailings, they also offered important advantages to the users of their services

and contributed to the competitiveness of the EU shipping industry. As a consequence,

the Commission proposed a regulation setting out the conditions under which consortia

are exempted from EU antitrust rules, which was adopted in 1995

4

and has, in essence,

remained effective since then.

1

Port Economics, Management and Policy, Value of Containerized Trade 2020, based on UNCTAD

data.

2

Communication by the Commission of 18 June 1990 – Report on the possibility of a group exemption

for consortia agreements in liner shipping – Proposal for a Council Regulation (EEC) on the

application of Article 85(3) of the Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and concerted

practices between shipping companies, COM(90) 260 final.

3

Containerisation is a logistics method in which a large amount of material (such as merchandise) is

packaged into large standardised containers.

4

Commission Regulation (EC) No 870/95 of 20 April 1995 on the application of Article 85(3) of the

Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and concerted practices between liner shipping

companies (consortia) pursuant to Council regulation (EEC) No 479/92, OJ L 89, 21.04.1995, p. 7.

4

The conditional exemption currently applicable to consortia is provided for in

Commission Regulation (EC) No 906/2009

5

(the “Consortia Block Exemption

Regulation” or “CBER”). The CBER is due to expire on 25 April 2024. In line with the

“evaluate first” principle under Better Regulation

6

, the CBER should be evaluated before

its expiry, so that the Commission can decide whether to let it expire or extend it again,

with or without modifications.

This evaluation report, in the form of a Staff Working Document (“SWD”), constitutes

the final product of the evaluation process of the CBER. It reflects the findings and views

of the Commission’s staff and does not necessarily reflect the formal position of the

Commission itself.

1.1. Purpose of the evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation was to gather facts and evidence on the functioning of the

CBER since its latest evaluation in 2019

7

and extension in 2020,

8

which serve as a basis

for the Commission to decide whether it should be left to expire on 25 April 2024 or

rather be extended again, with or without modifications.

As required by the Better Regulation Guidelines,

9

the evaluation examines the extent to

which the CBER fulfilled the five following criteria over the evaluation period: (i) it was

effective in fulfilling expectations and meeting its objectives (effectiveness); (ii) it was

efficient in terms of cost-effectiveness and proportionality of actual costs to benefits

(efficiency); (iii) it was relevant to current and emerging needs (relevance); (iv) it was

coherent internally and externally with other EU interventions or international

agreements (coherence); and (v) it produced results beyond what would have been

achieved by Member States acting alone (EU added value).

Accordingly, one of the main elements addressed by the evaluation of the CBER is

whether, over the evaluation period, block-exempted consortia continued to bring

5

Commission Regulation (EC) No 906/2009 of 28 September 2009 on the application of Article 81(3)

of the Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and concerted practices between liner

shipping companies (consortia), OJ L 256, 29.9.2009, p. 31.

6

See section II.3 of the European Commission 2019-2024 Working Methods; see also Better

Regulation Toolbox dated 25 November 2021, Tool #45 – What is an evaluation and when it is

required.

7

Commission Staff Working Document, Evaluation of Commission Regulation (EC) No 906/2009 of

28 September 2009 on the application of Article 81(3) of the Treaty to certain categories of

agreements, decisions and concerted practices between liner shipping companies (consortia),

SWD(2019) 411 final (the “2019 evaluation report”).

8

Commission Regulation (EU) 2020/436 of 24 March 2020 amending Regulation (EC) No 906/2009 as

regards its period of application, OJ L 90, 25.3.2020, p. 1.

9

Commission Staff Working Document, Better Regulation Guidelines, 3.11.2021, SWD(2021) 305

final.

5

efficiency gains which eventually benefitted transport users (shippers and freight

forwarders) through e.g. lower prices or better quality of services (greater connectivity,

greater availability or greater reliability). This element, which, in line with the 2019

evaluation report, forms part of the assessment of the compliance of the CBER with the

relevance criterion,

10

derives from the legal basis of the CBER, i.e. Article 101(3) of the

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”)

11

and Council Regulation No

246/2009

12

(the “Enabling Regulation”). According to the Enabling Regulation,

13

“Article

[101](1) TFEU may in accordance with Article [101](3) thereof be declared

inapplicable to categories of agreements, decisions and concerted practices that fulfil the

conditions contained in Article [101](3)”. Specifically, according to the Enabling

Regulation,

14

the Commission should, in the CBER, set out the requirements to be

fulfilled by consortia ensuring that all the conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU are met, “in

particular that a fair share of the benefits will be passed on to shippers.”

15

While neither the evaluation criteria for the CBER nor the competitive structure of the

liner shipping sector has substantially changed since the 2019 evaluation, the market

circumstances during the two evaluation periods are radically different. The trend

towards decreasing freight rates and greater availability of services that prevailed before

10

See 2019 evaluation report, p. 10: “In evaluating whether the Consortia BER is still relevant it is

examined whether consortia can still be considered economically efficient cooperation that also

benefits consumers.” As further explained in section 4.1.3 of the present evaluation report, this

element also forms part of the assessment of the compliance of the CBER with the coherence criterion.

11

Article 101(1) TFEU prohibits agreements between undertakings and concerted practices that restrict

competition. However, Article 101(3) TFEU provides that this prohibition may be declared

inapplicable to agreements or categories of agreements contributing to improving the production or

distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair

share of the resulting benefits. Pursuant to Article 103 TFEU, the Council should lay down detailed

rules for the application of Article 101(3) TFEU, taking into account the need to ensure effective

supervision on the one hand, and to simplify administration to the greatest possible extent on the other.

12

Council Regulation (EC) No 246/2009 of 26 February 2009 on the application of Article 81(3) of the

Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and concerted practices between liner shipping

companies (consortia), OJ L 79, 25.3.2009, p. 1. As of 1 December 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon

amending the TFEU and the Treaty establishing the European Community of 13 December 2007

(“TEC”) (OJ C 306, 17.12.2007, p. 1) renumbered the articles of the TEC. Articles 81 and 83 TEC

became respectively Articles 101 and 103 TFEU and remained, in substance, unchanged. According to

Article 5(3) of the Treaty of Lisbon, references to Articles 81 and 83 TEC in instruments or acts of EU

law are to be understood as referring to Articles 101 and 103 TFEU.

13

Enabling Regulation, recital (2).

14

Enabling Regulation, recital (10).

15

A consortium would meet all the conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU if: (i) the consortium contributes

to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress

(efficiency gains); (ii) the consortium allows consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit (pass-on to

consumers); (iii) the consortium does not impose on its members restrictions which are not

indispensable to the attainment of these objectives (indispensability); and (iv) the consortium does not

afford its members the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the liner

shipping services they jointly provide.

6

the COVID-19 pandemic was interrupted in 2020, with spot rates surging to reach a

historical peak in early 2022 for services of a much degraded quality (see section 3

below). The normalisation of the liner shipping sector since mid-2022 should not detract

from the need to draw lessons from the challenges faced by the maritime supply chain

over the last three years and to re-examine the role of consortia in the productivity of

liner shipping services, as well as the overall efficiency and resilience of the global

logistics system.

In particular, the extreme variations in the price and quality of liner shipping services

over the evaluation period call for an adjusted methodological approach to the

assessment of the causal link between block-exempted consortia and the consumer

benefits that they were expected to bring at the time of the adoption of the CBER (e.g.

lower prices and/or better service quality).

On the one hand, in prior reviews of the CBER, the approach consisted in assuming the

causal link between the existence of block-exempted consortia and benefits for the users

of their services and assessing whether the market developments over the evaluation

period raised any concern that consumers would not benefit from block-exempted

consortia any more.

16

As an illustration, for the 2019 evaluation, it was found that the parameters of

competition had not deteriorated during the evaluation period, in particular the costs for

carriers and prices for customers per TEU

17

had decreased in parallel and the quality of

services had remained stable. It was therefore concluded that there was no reason to

depart from the longstanding view that consortia were an efficient way for providing and

improving liner shipping services that also benefits customers.

18

On that basis, the

Commission was able to conclude with a sufficient degree of certainty, in spite of the

methodological limitations in the evaluations, that block-exempted consortia still

satisfied the conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU.

19

16

See the 2019 evaluation report, p. 11: “In accordance with the above, the Commission has applied the

same methodology in its reviews of Consortia BER: assessing the continuous existence of efficiencies

and their pass-on (absence of deterioration), rather than assessing their benchmark values. Similarly,

in its last review of the Consortia BER the Commission reaffirmed that the efficiency gains and

benefits, established at the adoption of that regulation, were still present at the time. The same

approach and point of comparison is applied in this evaluation, where the Commission looks at what

has happened or changed in the market since 2014 and assesses whether these developments raise any

concern that a fair share of efficiency gains or pass-on of benefits to consumers would not materialise

anymore.”

17

Containers usually come in two standard sizes (twenty-foot and forty-foot length). The CBER uses the

first one (twenty-foot equivalent units or TEUs) as a reference to establish the condition for exemption

relating to the market share of a consortium.

18

See 2019 evaluation report, p. 35.

19

See Commission Regulation (EU) 2020/436 of 24 March 2020 amending Regulation (EC) No

906/2009 as regards its period of application (OJ L 90, 25.3.2020, p. 1), recital (2); Commission

7

Such an approach cannot be followed for the present evaluation due to the price hikes

and service disruptions faced by transport users during the evaluation period. Regardless

of their temporary nature, and without prejudice to the exceptional combination of factors

to which they may be attributed, they remove the factual grounds on the basis of which,

in prior reviews of the CBER, the consumer welfare-enhancing effects of consortia had

been assumed and confirmed.

On the other hand, the volatility in the price and quality of services over the evaluation

period has incited carriers to submit not only qualitative but also quantitative elements to

substantiate the effects of consortia on the supply chain and consumers. The data and

studies provided by carriers notably aimed to isolate the effects, over the evaluation

period (2020-2023), of consortia and of the other main demand, supply and cost factors

that may influence the price and quality of liner shipping services on a trade (e.g. overall

demand level, bunker prices, productivity of the other operators along the supply chain,

degree of competition between carriers).

The prominence given by carriers in their feedback to the substantiation of the actual

consumer benefits attributable to block-exempted consortia nevertheless calls for two

words of caution.

First, the results of the quantitative analyses carried out or commissioned by carriers in

relation to the role of consortia (if any) in the massive freight increases in 2020-2022

should not be extrapolated to other periods, notably the period covered by the 2019

evaluation report, which was characterised by a clear trend in terms of price and service

quality. In addition, despite the analytical efforts of all categories of stakeholders, it has

not been possible, for the purpose of the present evaluation, to establish with a sufficient

degree of certainty

20

the causal effects of block-exempted consortia on the price and

quality of liner shipping services, due notably to methodological limitations (for example

difficulties in tackling “chicken and egg” type of problems, such as whether consortia

lead to an increase in the average size of vessels or whether the increase in the average

size of vessels leads to consortia) or the complex interrelations between the productivity

of carriers and of the operators upstream and downstream the supply chain. In other

words, it has not been possible, for the purpose of this evaluation, to find a

methodological approach that isolates the effects of the CBER from the general factors

affecting liner shipping.

In this context, particular attention has been paid in the present evaluation to collecting

evidence covering as comprehensively as possible all five evaluation criteria, not limited

to the relevance of the CBER in terms of consumer benefits generated by block-

Regulation (EU) No 697/2014 of 24 June 2014 amending Regulation (EC) No 906/2009 as regards its

period of application (OJ L 184, 25.6.2014, p. 3), recital (1).

20

See footnote 19 above.

8

exempted consortia, so as to be able to reach clear-cut conclusions as to the effectiveness,

efficiency, coherence and EU added value of the CBER.

Second, the evaluation of the CBER neither aims at – nor is capable of – determining

whether any specific consortium complies with Article 101 TFEU. This would require (i)

a determination of whether it prevents, restricts or distorts competition and is thus caught

by the prohibition of Article 101(1) TFEU; and, if so, (ii) a balanced assessment of both

its adverse effects on competition on the relevant market (which may differ from a trade)

and its pro-competitive effects. This goes beyond the purpose of the evaluation. For

block-exempted consortia, the evaluation only addresses, as part of the relevance

criterion, the question of whether sufficient evidence supports their pro-competitive

effects, as identified by stakeholders during the consultation process. The evaluation does

not attempt to quantify those pro-competitive effects, since the CBER was adopted in

2009 without providing any quantitative benchmarks for the efficiency gains or benefits

to consumers.

21

For consortia not benefitting from the CBER, as recalled in the CBER,

there is no presumption that they fall within the scope of Article 101(1) TFEU or, if they

do, that they do not satisfy the conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU.

22

Therefore, the

evaluation does not address the question of whether consortia outside of the CBER fall

within the scope of prohibited agreements under Article 101 TFEU.

1.2. Scope of the evaluation

The substantive scope of the evaluation is the CBER, which applies to consortia only in

so far as they provide international liner shipping services from or to one or more EU

ports.

23

Trades not involving an EU port (e.g. transpacific trades) are not covered by the

CBER. Therefore, they are taken into account in the evaluation only to the extent that the

liner shipping services provided on those trades had an impact on the services provided

on trades to or from the EU or shed some light on the systemic, overall functioning of the

sector.

The CBER is the only remaining block exemption from EU antitrust rules in the

maritime sector. The Liner Conference Block Exemption Regulation,

24

which exempted

agreements between liner shipping companies on prices and other conditions of carriage

on routes to and from the EU, was repealed with effect from 18 October 2008.

25

The

21

See 2019 evaluation report, p. 10.

22

See CBER, recital (4).

23

See CBER, Article 1.

24

Council Regulation (EEC) No 4056/86 of 22 December 1986 laying down detailed rules for the

application of Articles 85 and 86 of the Treaty to maritime transport, OJ L 378, 31.12.1986, p. 4.

25

Council Regulation (EC) No 1419/2006 of 25 September 2006 repealing Regulation (EEC) No

4056/86 laying down detailed rules for the application of Articles 85 and 86 of the Treaty to maritime

transport, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 as regards the extension of its scope to include

cabotage and international tramp services, OJ L 269, 28.9.2006, p. 1.

9

Antitrust Maritime Guidelines

26

issued by the Commission in 2008 to, notably,

accompany carriers following the end of the conference system, were left to expire in

2013.

The temporal scope of the evaluation is the 2020-2023 period, i.e. the period between the

latest extension of the CBER in 2020

27

and the date of the drafting of this document.

The geographic scope of the evaluation extends to all Member States.

28

Article 101(1) of

the Treaty has direct applicability in all Member States by virtue of the case law of the

Union courts.

Regulation (EC) No 1/2003

29

created a system of parallel competences in which the

competition authorities and the courts of the Member States, alongside the Commission,

have the power to apply not only Article 101(1) TFEU, but also Article 101(3) TFEU.

When assessing the compatibility of consortia that may affect trade between Member

States within the meaning of Article 101 TFEU,

30

national competition authorities and

national courts are bound by the directly applicable provisions of the CBER. Thus, apart

from the Commission, national competition authorities and national courts are

responsible for the administrative supervision of consortia, the simplification of which is

one of the two specific objectives of the CBER defined for the purposes of this

evaluation (see section 4.1.2 below).

26

Guidelines on the application of Article 81 of the EC Treaty to maritime transport services, OJ C 245,

26.9.2008, p. 2.

27

The 2019 evaluation report covered the 2014-2019 period, so that there is no gap between the two

evaluation periods.

28

The United Kingdom (UK) withdrew from the European Union as of 1 February 2020. According to

Article 92 of the Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern

Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community (OJ L 29, 31.1.2020,

p. 7), the Commission continued to be competent to apply Union law as regards the UK for

administrative procedures which were initiated before the end of the transition period on 31 December

2020. In this context, the external contractor in charge of the fact-finding study in 2020-2021 has

collected data on consortia active in the EU and in the UK and confirmed that the UK’s withdrawal

had no material impact on the number or market position of consortia active to and from the EU. In

addition, since the consultation activities for this evaluation were initiated after the end of the

transition period, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority was not invited to contribute as part of

the European Competition Network. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority is currently

reviewing the CBER that was retained in UK law following the end of the transition period.

29

Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002 on the implementation of the rules on

competition laid down in Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty, OJ L 1, 4.1.2003, p. 1 (“Regulation (EC)

No 1/2003”).

30

Liner shipping services are often international in nature linking EU ports with third countries and/or

involving exports and imports between two or more Member States. In most cases, they are thus likely

to affect trade between Member States.

10

In view of the Commission’s obligation to informally seek advice from experts of the

EEA EFTA States for the elaboration of new legislative proposals,

31

the Commission has

informed those States of the evaluation of the CBER in order to provide them with an

early opportunity to share their experience in this regard.

2. WHAT WAS THE EXPECTED OUTCOME OF THE INTERVENTION?

2.1. Description of the intervention

In essence, the CBER is a competition law instrument “legalising” certain consortia.

32

More specifically, the CBER sets out the conditions under which consortia are exempted

from the prohibition of agreements between competitors set out in Article 101(1) TFEU.

Consortia are defined as joint service agreements between carriers designed to rationalise

their operations.

33

Although consortia may be organised in many forms, they generally

fall within three categories, which involve varying degrees of cooperation.

34

The least

integrated form of consortium is a slot

35

exchange agreement, in which carriers exchange

space on each other’s vessels operated on a given trade.

36

The second form of consortium

is a vessel sharing agreement, in which each carrier contributes vessels to a given service

on a trade and is entitled to a number of slots on all vessels contributed to the service,

proportionate to its vessel contribution. The most integrated form of consortium is an

alliance, in which carriers pool a pre-decided number of vessels contributed by each of

them and operate these vessels jointly on a number of trades.

The Commission acknowledges in the CBER that, due to the seasonality and cyclicality

of demand for liner shipping services, an essential component of consortia is the ability

to adjust capacity deployed on the trade in response to changing supply and demand

conditions.

37

31

Agreement on the European Economic Area, Article 99(1).

32

See Enabling Regulation, recital (6).

33

See Enabling Regulation, recital (5).

34

Stand-alone slot charter or purchase agreements, whereby a carrier buys space on vessels of another

carrier, are not reciprocal and do not involve the provision of joint services. Therefore, they are not

consortia within the meaning of the CBER.

35

A slot is the space for a container on-board a container ship.

36

A slot exchange agreement (also called “swap agreement”) whereby a carrier makes available space on

vessels operated on a trade and obtains, in exchange, space on another carrier’s vessels operated on a

different trade does not involve the provision of a joint service, which implies the operation of two

carriers on the same trade. Therefore, it is not a consortium within the meaning of the CBER.

37

CBER, Article 3(2).

11

The CBER contains three types of conditions for exemption. First, consortia may not

contain hardcore restrictions.

38

These refer to price fixing, capacity or sales limitations

(except capacity adjustments in response to fluctuations in supply and demand) and the

allocation of markets or customers. Second, the exemption applies to consortia with

combined market shares not exceeding 30% on the relevant market on which they

operate.

39

Third, consortia must give members the right to withdraw with a maximum

period of notice of 6 months (12 months in case of a highly integrated consortium).

40

Those conditions are meant to ensure that, although consortia allow carriers to

coordinate, and therefore remove differentiation, on certain service parameters (e.g. ports

of call, frequency, transit time, historical schedule reliability), block-exempted consortia

are unlikely to give rise to a restriction of competition or if they do, their positive effects

are likely to outweigh their restrictive effects.

2.2. Description of the objectives of the intervention

The CBER aims at contributing to the improvement of the competitiveness of the EU

liner shipping industry and the development of EU trade.

41

The overall aim of the CBER

pertains to Sustainable Development Goal 9 (“Build resilient infrastructure, promote

inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation”), Target 9.1 (“Develop

quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and

transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with

a focus on affordable and equitable access for all”).

General objective of the CBER

The general objective of the CBER is to protect effective competition in the liner

shipping sector for the benefit of EU transport users, by promoting ways of cooperation

between carriers which are economically desirable and without adverse effects from the

point of view of competition.

42

In other terms, the general objective of the CBER is to

facilitate the creation and operation of consortia, to the extent that they do not pose risks

to effective competition.

43

38

CBER, Article 4.

39

CBER, Article 5.

40

CBER, Article 6.

41

See Enabling Regulation, recital (6).

42

See Enabling Regulation, recital (8). The CBER shares the same general objective as the other

interventions on the application of Article 101 TFEU to cooperation between undertakings operating at

the same level of supply chain, including actual or potential competitors (“horizontal agreements”), in

particular Commission Regulation (EU) No 1218/2010 of 14 December 2010 on the application of

Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to categories of specialisation

agreements, OJ L 335, 18.12.2010, p. 43 (the “Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation”).

43

See 2019 evaluation report, p. 9.

12

This general objective draws from findings in 2009 about both: (i) the efficiency gains

and consumer benefits brought by consortia between small and medium-sized carriers

(e.g. improved frequency of sailings and port coverage, better quality and personalised

services); and (ii) the role of these consortia in preventing the creation of oligopolistic

market structures.

44

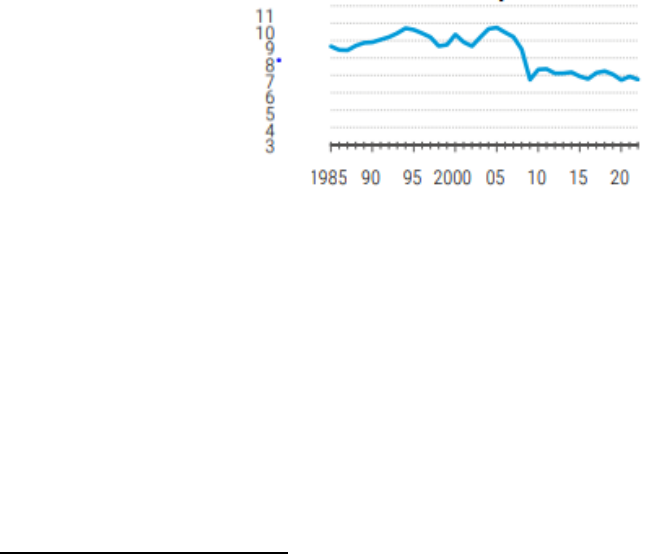

Regarding point (i), at the date of the adoption of the CBER (2009) and of its renewals

(2014 and 2020), consortia were found to generally help to improve the productivity and

quality of available liner shipping services by reason of the rationalisation they bring to

the activities of their members and through the economies of scale they allow in the

operation of vessels and utilisation of port facilities. The graph below (Figure 1)

illustrates the economies of scale (lower cost per slot available) that were expected to be

achieved through the use of larger vessels.

45

Figure 1: Ship System Cost (USD per TEU) Asia-North Europe service (round trip)

Source: Drewry, Consolidation in the liner industry, White Paper, March 2016

Consortia were also found to have promoted technical and economic progress by

facilitating and encouraging greater utilisation of containers and more efficient use of

vessel capacity. In addition, users were found to benefit from the improvement in

productivity brought by consortia, in the form of an improvement in the frequency of

sailings and port calls, or an improvement in scheduling as well as better quality and

44

Those findings echo those on the basis of which the Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation was

adopted. It was considered that specialisation agreements (including joint production agreements)

generally contribute to improving the production process and that they are particularly suited to

strengthen the competitive position of small- and medium-sized firms (see Commission Staff Working

Document, Evaluation of the Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations, SWD(2021) 103 final, p. 9).

45

It is acknowledged that there is no consensus on the achievement of economies of scale for the largest

vessels (see e.g. feedback from Ulrich Malchow in response to the call for evidence, indicating that,

above a certain size of ships, fuel use, and thus emissions, and total cost per TEU increase again). This

will be discussed as part of the assessment of the relevance criterion. Nevertheless, such lack of

consensus does neither call into question the initial purpose of the CBER nor the achievement of

significant economies of scale for most vessel categories.

13

personalised services, provided that consortia were subject to sufficient external

competition.

46

The description above of the pro-competitive effects of consortia corresponds to the more

general description of the favourable economic effects of joint production or

specialisation agreements (of which consortia are a form) in the latest evaluation report

of the Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation, i.e. the achievement of economies of

scale or, in a wider sense, in rationalisation measures which enable firms to cut costs by

concentrating operations. Such measures should lead, in conditions of effective

competition, to lower prices and thus benefit the consumer.

47

Regarding point (ii), at the date of the adoption of the CBER (2009), the liner shipping

sector was still considered as relatively fragmented with low levels of concentration, not

only on a global scale, but also on a trade-by-trade basis. As examples, in 2008, on each

of the four large East-West trades, i.e. from North Europe or Mediterranean to the Far

East or North America, more than 20 carriers offered services, out of which at least five

were operated individually.

48

However, only a limited number of individual carriers had the financial resources to bear

the upfront investment for the acquisition of larger, more efficient vessels and had the

route coverage to maintain a sufficiently high utilisation rate.

49

Consortia between small

or medium-sized carriers were seen as a way for them to maintain their ability to compete

with larger carriers, in particular the top-three carriers (Maersk, MSC, CMA CGM)

which had engaged in a race for scale to win cost leadership. Consortia were notably

considered indispensable for smaller carriers to bridge the capacity and frequency gap

with Maersk, MSC and CMA CGM on the Far East-Europe trades.

50

Furthermore, it was recognised that demand for liner shipping services was also seasonal

and cyclical and, notably due to the structural trade imbalance,

51

prone to overcapacity. In

46

CBER, recitals 5 to 7.

47

Commission Staff Working Document, Evaluation of the Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations,

SWD(2021) 103 final, p. 9.

48

Commission services document, Technical paper on the revision of Commission Regulation (EC) No

823/2000 on the application of Article 81(3) of the Treaty to certain categories of agreements,

decisions and concerted practices between liner shipping companies (consortia), as last amended by

Commission Regulation (EC) 611/2005 of 20 April 2005 (the “2008 technical paper”), points 33 and

34.

49

See COM(90) 260 final, p. 2.

50

In 2009, none of those three carriers were members of integrated consortia (alliances). The latter (New

World, Grand, CKHY) were rather used by small and medium-sized carriers.

51

For example, China’s position in global manufacturing means that exports of containerised cargo from

China largely exceed imports, so that the demand for liner shipping services from China to Europe

largely exceeds the demand for services from Europe to China. The capacity deployed on a round trip

14

this context, small and medium-sized carriers without strong financial resources were

considered as being in a particularly vulnerable situation if they were operating on a

stand-alone basis.

52

The specific added value of consortia for smaller carriers has been consistently used as a

justification in connection with subsequent reviews of the CBER.

53

Specific objectives

The CBER has two specific objectives. First, it aims to provide legal certainty to carriers,

in particular small and medium-sized ones, as to the forms of cooperation that can be

considered as compliant with Article 101 TFEU.

54

Second, it aims to simplify

administrative supervision by providing a common framework for the Commission,

national competition authorities and national courts for assessing cooperation between

carriers under Article 101 TFEU.

55

These specific objectives are better understood in the context of the changes in the

general and sectorial legal framework for applying Article 101 TFEU introduced by

Regulation (EC) No 1/2003.

Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 abolished the system of notification of cooperation

agreements to the Commission which had prevailed before its entry into force.

Companies therefore can no longer notify their agreements to the Commission in order to

exclude the existence of an infringement and, notably, benefit from immunity from fines.

They have to self-assess the compliance of their agreements with Article 101 TFEU.

Self-assessment may, in certain circumstances, create a significant burden, especially for

SMEs, which may lack the necessary resources or legal expertise. Regulation (EC) No

is set by reference to the dominant leg of the trade (i.e. from Far East to North Europe or to the

Mediterranean), which is the main contributor of revenues on the trade.

52

See COM(90) 260 final, p. 2.

53

See e.g. Commission Vestager, EMLO Conference, 5 October 2015: “Consortia are a logical

response to the difficulties that beset the industry and we know that they can create efficiencies. Both

small and large carriers see benefits; for smaller carriers, consortia are often the only way to offer a

regular service.”

54

See 2019 evaluation report, p. 9: “The Consortia BER achieves this objective by providing consortia

with clarity and legal certainty with respect to their compliance with EU competition rules.” The

reference to the specific need for legal certainty for smaller carriers is to be found in the section

assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of the CBER (see e.g. “[Carriers and their associations]

argue that in [the CBER] absence legal uncertainty and increased legal fees (due to the need to

conduct complex self-assessment) will have a chilling effect on consortia, mostly on the smaller ones”,

p. 18 on effectiveness, or “The respondent carriers argue that the increased assessment costs may

discourage the small carriers from entering into consortia agreements”, p. 19 on efficiency).

55

This specific objective was not referred to in the 2019 evaluation report. However it directly derives

from Article 103 TFEU, which sets out the need to ensure effective supervision where laying detailed

rules for the application of Article 101(3) TFEU (see footnote 11 above).

15

1/2003 also decentralised the application of Article 101(3) TFEU by empowering

national competition authorities and national courts, alongside the Commission, to apply

Article 101(3) TFEU, which in the past was a prerogative of the Commission only. This

decentralised enforcement system created a need to foster a consistent application of

Article 101 TFEU and ensure that companies operating across the EU could benefit from

a level playing field.

In addition to those changes in the general legal framework applicable to cooperation

agreements, the adoption of the CBER in 2009 took place in the particular context of the

repeal of the Liner Conference Block Exemption, which introduced an important change

in the specific legal framework applicable to the liner shipping markets.

56

Maintaining the

block exemption for consortia was considered as a means to facilitate the transition of the

industry to the standard competition regime applied to all other economic sectors.

57

56

Shipping companies had organised themselves since the nineteenth century in the form of liner

conferences to fix prices and regulate capacity. Liner conferences were most prevalent on routes

between Europe, on the one hand, and North America and the Far East, on the other hand. They were

associations of shipowners operating on the same route, served by a secretariat. The Liner Conference

Block Exemption Regulation allowed them to set common freight rates, to take joint decisions on the

limitation of supply and to coordinate timetables. The exemption had been granted on the assumption

that it was necessary to ensure the provision of reliable services. The repeal of the Liner Conference

Block Exemption Regulation put an end to the possibility for liner carriers to meet in conferences, fix

prices and regulate capacities on routes to and from Europe as of October 2008.

57

See 2008 technical paper, point 15.

16

Logic of the CBER

The figure below (Figure 2) summarises the intervention logic of the CBER.

Figure 2: Intervention logic for the CBER

Needs

General objective

• To protect effective competition in the liner shipping sector for the benefit of

EU transport users

Specific objectives

• To provide legal certainty to carriers, in particular small and medium-sized

ones, as to the forms of cooperation compliant with Article 101 TFEU

• To simplify administrative supervision of cooperation between carriers

Objectives

Inputs

• Definition of the cooperation agreements that may be block-exempted and

may not be block-exempted (hardcore restrictions)

• Definition of the conditions for the block exemption of consortia

Outputs

• Carriers using the CBER to self-assess compliance with Article 101 TFEU

• National competition authorities and national courts applying Article 101(3)

TFEU based on the CBER

Results

Impact

External factors

• Global economic growth or recession impacting demand for containerised goods

• Modification in trade patterns (due to e.g. trade tensions, protectionism, relocation of

production)

• In- or outsourcing by shippers

• Fluctuations in operating costs of carriers (e.g. fuel)

• Change in the regulatory framework applicable to liner shipping (e.g. environmental

regulations)

• Supply chain disruptions (due to e.g. lockdowns, strikes, weather events)

• Technological developments (e.g. digitalisation)

• Legal certainty for carriers, in particular small and medium-sized ones, as to

the forms of cooperation compliant with Article 101 TFEU

• Simplified administrative supervision of cooperation between carriers

• Effective competition in the liner shipping sector for the benefit of EU

transport users

• To contribute to the improvement of the competitiveness of the EU liner

shipping industry

• To contribute to the development of EU trade

17

2.3. Points of comparison

The point of comparison for the assessment of the effectiveness of the CBER consists in

assessing the extent to which the CBER has fulfilled its two specific objectives, i.e. (i) to

provide legal certainty to carriers, in particular small and medium-sized ones, as to the

forms of cooperation that can be considered as compliant with Article 101 TFEU, and (ii)

to simplify administrative supervision by providing a common framework for the

Commission, national competition authorities and national courts.

The point of comparison for the assessment of the efficiency of the CBER consists in

assessing the savings in compliance costs and time achieved by carriers thanks to the

CBER, in addition to assessing the extent to which the CBER has fulfilled its two

specific objectives (same point of comparison as for the assessment of the effectiveness

of the CBER).

The point of comparison for the assessment of the coherence of the CBER consists in

looking at the changes during the evaluation period (2020-2023) resulting from the

review of the other rules and guidance for carriers to self-assess compliance of consortia

with Article 101 TFEU, in particular the Commission Horizontal Guidelines

58

and the

Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation.

59

That point of comparison also includes

the changes in other applicable EU and international rules, most notably the initiatives

aimed at decarbonising the sector (e.g. inclusion of maritime emissions in the EU

Emissions Trading System (ETS)

60

and mandatory energy efficiency requirements set by

the International Maritime Organization).

The point of comparison for the assessment of the EU added value of the CBER consists

in assessing whether it has achieved its operational objective of creating a legal

framework supporting the competitiveness of small and medium-sized carriers active on

EU trades.

58

Version applicable until 20 July 2023: Commission Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 of

the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to horizontal co-operation agreements, OJ C11,

14.1.2011, p. 1; version applicable as from 21 July 2023: Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101

of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to horizontal co-operation agreements, OJ C

259, 21.7.2023, p. 1.

59

Version applicable until 30 June 2023: Commission Regulation 1217/2010/EU of 14 December 2010

on the application of Article 101(3) TFEU to certain categories of specialisation agreements, OJ L 335,

18.12.2010, p. 43; version applicable as from 1 July 2023: Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/1067 of

1 June 2023 on the application of Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European

Union to certain categories of specialisation agreements, OJ L 143, 2.6.2023, p. 20.

60

Directive (EU) 2023/959 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 amending

Directive 2003/87/EC establishing a system for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the

Union and Decision (EU) 2015/1814 concerning the establishment and operation of a market stability

reserve for the Union greenhouse gas emission trading system (OJ L 130, 16.5.2023, p. 134); and

Regulation (EU) 2023/957 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 amending

Regulation (EU) 2015/757 in order to provide for the inclusion of maritime transport activities in the

EU Emissions Trading System and for the monitoring, reporting and verification of emissions of

additional greenhouse gases and emissions from additional ship types (OJ L 130, 16.5.2023, p. 105).

18

The points of comparison for the assessment of the relevance of the CBER are the

original needs and objectives behind the CBER (i.e. to contribute to the improvement of

the competitiveness of the EU liner shipping industry and the development of EU trade)

and the new needs arising from, notably, the changes in the market structure as well as

the economic, environmental and technological challenges faced by the sector.

The main source used for those points of comparison is the latest 2019 evaluation report.

3. HOW HAS THE SITUATION EVOLVED OVER THE EVALUATION PERIOD?

3.1. State of play in 2019

In the 2019 evaluation report, it was concluded that the CBER was relevant and

delivering on its objectives, considering the state of the liner shipping industry over the

2014-2019 period. That conclusion was principally based on the following market

circumstances: (i) consortia played a major role in the sector and were expected to

continue to do so in the medium term due to over-capacity, low prices and low

profitability; (ii) the level of concentration in the liner shipping sector had increased in

recent years; although requiring close monitoring, this trend was not found to have

negatively affected consumers; and (iii) both costs for carriers and prices for customers

per TEU had decreased by approximately 30% and levels of services had remained stable

since 2014.

3.2. Current state of play

Over the 2020-2023 evaluation period, consortia remained a prevalent feature of the

sector. This is without prejudice to the increasing tendency of certain large carriers to run

their networks on a stand-alone basis, by operating services outside of their alliance, and

the announcement of the dissolution of the 2M alliance in 2025. In 2020, approximately

43 unique

61

consortia operated in the EU (excluding intra-North Europe and intra-

Mediterranean services). Those included the three global alliances,

62

which were made of

the nine largest carriers worldwide after South Korean HMM joined THE Alliance as a

61

A “unique” consortium (or “deduplicated” consortium) corresponds to a consortium as defined in

Article 2(1) of the CBER (an agreement or a set of interrelated agreements relating to one or more

trades). This means that an agreement or a set of interrelated agreements relating to two trades will be

counted as a unique consortium. Defining one distinct consortium per relevant geographic market

(“duplicating” a multi-trade consortium) would be at odds with the provisions of the CBER on the

definition of a consortium (Article 2(1) of the CBER) and the scope of the exemption (Article 3 of the

CBER exempts the activities of a consortium on the relevant market or markets, as referred to in

paragraph 4).

62

Each of the three global alliances, made up of the nine largest carriers worldwide (which together

represents 83% of the global capacity; the capacity dedicated to the alliances by those carriers

represents 39% of the global capacity), accounts for one consortium, although it is made of a number

of interrelated cooperation agreements covering a number of joint services and trades.

19

full member in 2020, representing more than 80% of the global capacity.

63

The table

below gives an overview per trade

64

of the approximately 43 unique consortia active in

the EU in 2020.

65

The fourth column of the table below reflects the condition related to

market share set out in Article 5 of the CBER. For the sake of clarification, the reference

to “the relevant market” in Article 5 of the CBER is interpreted as a reference to “the

relevant market or markets” as for the other conditions for exemption set out in Article 6

of the CBER.

66

It should be recalled that, in the version of the CBER that expired on 25

63

The 2019 evaluation report refers to approximately 64 consortia (including the three global alliances)

operating in the EU, out of which between 9 and 29 had a market share below the 30% threshold set

out in the CBER. This estimate relied on the 2018 submission by the World Shipping Council, which

had used a different methodology to avoid double counting consortia providing different services,

including agreements between feeder providers on an intra-regional basis while accounting for vessel-

sharing agreements only (and not slot exchange agreements).

Due to the methodological issues for the calculation of the market shares described in the 2019

evaluation report (see notably p. 10), it had not been possible to more specifically estimate the number

of consortia below the 30% threshold set out in the CBER, nor to establish their profile, including the

types of carriers belonging to the consortia (e.g. large carriers active worldwide or smaller carriers) or

the interlinkages with other consortia active on the trade.

64

Considering that the CBER applies only to joint liner services to or from an EU port (see Article 1 of

the CBER), only trades to and from the EU are taken into account. Non-EU trades are not relevant

markets and the market share of a consortium on non-EU trades has no impact on whether the

consortium complies with the CBER condition related to market share and may be exempted under the

CBER.

65

This table results from the market reconstruction exercise undertaken by the Commission on the basis

of the fact-finding questionnaires sent in December 2021, as referred to in the Call for Evidence in the

“data collection and methodology” section, as well as data provided by the external contractor MDS

Transmodal. The number of consortia and their market shares should be considered as estimates, as it

has not been possible to fully reconcile the data provided by the different carriers due to, notably, the

differences in defining the relevant geographic markets, identifying the consortia to which they are

members, listing the other members of those consortia and computing the market shares. Regarding

the definition of the relevant geographic markets, for the purposes of the evaluation of the CBER, an

approach per trade has been adopted. This should not be considered as prejudging the market

definition that would be adopted when assessing a specific consortium under Article 101 or 102

TFEU.

66

This interpretation is illustrated by the Commission’s approach to the (eventually abandoned) alliance

between Maersk, MSC, and CMA CGM (P3 Network or “P3”) and the alliance between APL, Hapag-

Lloyd, Hyundai, MOL, NYK, and OOCL (G6 Alliance or “G6”), which were considered to fall

outside of the CBER for exceeding the 30% market share threshold on at least one of the relevant

markets on which they operated. In June 2014, the Commission recalled: “Members of all shipping

alliances such as P3 or G6, to the extent that they do not benefit from an exemption, must themselves

assess the legality of their agreements under EU competition rules” (see press report of 4 June 2014,

“No challenge to P3 in Europe”: https://www.freightwaves.com/news/no-challenge-to-p3-in-europe).

See also written contribution from the European Union submitted for Item IV of the 59

th

meeting of the

OECD Working Party No. 2 on Competition and Regulation on 19 June 2015, “Competition issues in

liner shipping”, point 35: “The P3 alliance could not benefit from the safe harbour of the Consortia

BER because it appeared that the market share of the combined entity would exceed the 30% market

share threshold. The P3 parties had, therefore, to conduct their own self-assessment of the planned

cooperation to determine whether or not it was compliant under Article 101(1) TFEU and if not,

whether it creates efficiencies and pass-on to customers (and the other conditions of Article 101(3)

TFEU)”

(https://ec.europa.eu/competition/international/multilateral/2015_june_liner_shipping_en.pdf).

20

April 2010, the exemption of a consortium was conditioned upon the consortium

possessing a market share of under 30% or 35% on each market upon which it operates.

67

The changes introduced in the CBER as adopted in 2009 were not meant to alter the

requirement that the market share threshold should be respected on each of the relevant

markets.

68

As explained in recital (2) of the CBER, the modifications introduced in the

previously applicable CBER were necessary to remove references to the Liner

Conference Block Exemption Regulation and ensuring a greater convergence with other

block exemption regulations for horizontal cooperation.

Trade

Number of

consortia

69

of which no

member is a top-

five carrier

(Maersk, MSC,

CMA CGM,

COSCO, Hapag-

Lloyd)

Number of

consortia with

market share <

30% on all trades

on which they are

active

70

of which no

member is part

of non-exempted

consortia on the

same trade

North Europe - Far East

3

0

0

0

Med - Far East

3

0

0

0

North Europe - North

America

7

0

2

0

Med - North America

6

0

3

0

North Europe - Indian

Subcontinent

4

0

1

0

Med - Indian Subcontinent

2

0

0

0

67

See Article 6(1) of Commission Regulation (EC) No 823/2000 on the application of Article 81(3) of

the Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and concerted practices between liner

shipping companies (consortia) (OJ L 100, 20.4.2000, p. 24): “In order to qualify for the exemption

provided for in Article 3, a consortium must possess on each market upon which it operates a market

share of under 30 % calculated by reference to the volume of goods carried (freight tonnes or 20-foot

equivalent units) when it operates within a conference, and under 35 % when it operates outside a

conference.” The same reference to “each market” was used in the Commission’s preliminary draft

for the CBER (see Notice pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation (EEC) No 479/92 on the

application of Article 81(3) of the EC Treaty to certain categories of agreements, decisions and

concerted practices between liner shipping companies (‘consortia’), OJ C 266, 21.10.2008, p. 1).

68

See memo of 28 September 2009, “Antitrust: Commission adopts new Block Exemption Regulation

for liner shipping consortia - frequently asked questions”: “The 30% market share threshold provided

by the new Regulation already applied to a large number of consortia in the past, as this was the

market share threshold applicable to consortia which operated within the former liner conference

system” (ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_09_420).

69

Non-deduplicated. In other terms, one consortium active on two trades will be counted as two. This

explains why the total number of consortia listed in this column exceeds the total of 43 unique

consortia active in the EU.

70

Non-deduplicated. Out of the 14 consortia listed in this column, one is active on two trades, which

explains why the number of unique consortia operating in the EU with a market share below 30% on

all trades on which they are active is 13 (see section 4.1.1 below).

21

North Europe - Middle East

4

0

1

0

Med - Middle East

2

0

0

0

North Europe - Australasia

& Oceania

2

0

1

0

Med - Australasia &

Oceania

1

0

0

0

North Europe - South

America West Coast

3

0

0

0

Med - South America West

Coast

0

0

0

0

North Europe - South

America East Coast

2

0

0

0

Med - South America East

Coast

3

0

0

0

North Europe - Central

America & Caribbean

3

0

0

0

Med - Central America &

Caribbean

3

0

1

0

North Europe - West Africa

2

0

2

2

Med - West Africa

3

0

2

0

North Europe - South

Africa

1

0

0

0

Med - South Africa

1

0

0

0

North Europe - East Africa /

Indian Ocean Islands

1

0

0

0

Med - East Africa / Indian

Ocean Islands

1

0

0

0

North Europe - Med

3

0

1

0

The shares of capacity deployed by consortia per trade also illustrate the prevalence of

consortia over the evaluation period. They reached between 40% on the Europe-South

America West Coast trade and 100% on the Far East-Europe trades in 2020, where the

available capacity was almost exclusively attributable to the members of the three global

alliances.

71

A number of smaller carriers entered the latter trades in 2021, in order to take

advantage of high freight rates. However, those new entrants added only very limited

capacity to incumbent carriers (less than 3%) and are now phasing out (e.g. Allseas,

China United Lines), overburdened by unsustainable charter rates and a fading demand.

By contrast with the stability seen in the prevalence of consortia,

72

the evaluation period

has been characterised by dramatic changes in other market circumstances that,

according to the 2019 evaluation report, drove the need for cooperation between carriers.

More specifically, the evaluation period has seen a transitory and exceptional phase of

excess demand over effective capacity (see Figure 3) and of record profits for carriers

71

Data submitted by the World Shipping Council.

72

As indicated, consortia remained prevalent even though large carriers became less reliant on alliances.

22

(see Figure 4). This transitory and exceptional phase has temporarily interrupted the trend

towards oversupply and low profitability in the sector.

Figure 3 – Global and East-West supply-demand index 2019-2024e

Note: A figure of 100 represents equilibrium between supply and demand; above 100 demand exceeds

supply; below 100 the opposite.

Source: Drewry Container Forecaster Quarter 2 – June 2023

Figure 4 – Profitability of container liner shipping industry 2019-2024e

Source: Drewry Container Forecaster Quarter 2 – June 2023

In terms of the level of concentration during the evaluation period, the liner shipping

sector did not undergo any major operation of horizontal consolidation, as illustrated by

the flat shares of global capacity controlled by the top-four, top-10 and top-20 carriers

(see Figure 5). The German carrier Hapag-Lloyd nevertheless acquired two small

shipping lines focussed on Africa (Deutsche Afrika-Linien and NileDutch).

23

Figure 5 – Shares of global capacity of top-four, top-10 and top-20 carriers

2011-2022

Source: UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport 2022

The trend towards vertical integration of carriers continued, with substantial investments

in port and terminal operations. The four largest carriers are now among the top ten

terminal operators worldwide, with COSCO and Maersk controlling respectively 13%

and 11% of the global terminal throughput.

73

In addition, they have expanded their

operations into logistics, notably Maersk and CMA CGM that pursue a strategy of

offering end-to-end supply chain solutions to their customers.

In terms of freight rates, the evaluation period witnessed an extreme example of the

“boom and bust” cycle in the liner shipping industry (see Figure 6).

73

UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport 2022, p. 138, referring to Drewry (2022), Table 4.1: Global

terminal operators’ throughput league table, 2021 per cent share of world container port throughput in

TEU.

24

Figure 6 – 10‐Year Alphaliner Charter Rate Index and Freight Rate Indices

74

Source: Alphaliner, Monthly Monitor – May 2023

At the beginning of 2020, rates remained relatively stable, as carriers, which at the time

had historically low order books, swiftly removed capacity from trades affected by a

lowering of demand in the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak. Later in 2020, with

economic stimulus packages and a shift of household spending from services to goods,

demand for containerised transport increased on key routes, most notably on Far East-

North America, while an increasing share of the global shipping capacity was taken out

of the market due to supply chain blockages in ports and on land. As a result, freight rates

steeply increased and peaked in January 2022, before collapsing in 2022 when demand

deteriorated (reaching below 2019 levels in some trades), port congestion started to ease

and newly ordered ships entered the market.

In January 2023, the SCFI was just 10% higher than 2019 levels, although the rapid pace

of decline of the SCFI down to close to pre-COVID levels still concealed heterogeneous

situations per trade (see Figure 7).

74

The CCFI (China Containerized Freight Index) and the SCFI (Shanghai Containerized Freight Index)

are widely used indices. The CCFI is a composite of spot rates and contractual rates which reflects the

change in freight rates on 12 trade lanes to and from China using the index as of 1 January 1998, as

1 000 basis points. The SCFI shows, on a weekly basis, the most current freight prices (spot rates) for

container transport from the Chinese main ports, including Shanghai (Chinese export). Other used

indices, such as the Freightos Baltic Index (FBX) or Drewry’s composite World Container Index

(WCI), would show similar variations.

25

Figure 7 – Freight rates per trade – January 2023 vs 2019

Source: HSBC, Global Freight Monitor, 4 February 2023, based on Clarkson, Refinitiv Datastream

The pressure on freight rates is expected to remain in the short- to medium-term due to

the easing of supply chain congestion and the delivery of new containerships (as of 1

June 2023, the orderbook-to-fleet ratio stood at 28%, based on capacity).

75

At the end of

2022, the effective capacity was predicted to rise by 19% in 2023.

76

The vessel delays caused by and worsening the port and landside bottlenecks also

degraded the quality of liner shipping services during the evaluation period. In terms of

service availability, carriers adjusted their networks by allocating their vessels onto

shorter services calling at only two world regions (i.e. shuttles) instead of services

serving multiple regions. This led to a decrease in direct connectivity (i.e. number of

country pairs that can be reached without transhipment)

77

over the evaluation period

(2020-2023), a phenomenon that had nevertheless started before the COVID-19 crisis

(see Figure 8).

75

Drewry Container Forecaster Quarter 2 – June 2023.

76

Drewry Container Forecaster Quarter 4 – December 2022.

77

According to UNCTAD, counting on a direct regular shipping connection has empirically been shown

to help to reduce trade costs and increase trade volumes. Research shows that the absence of a direct

connection is associated with a 42% lower value of bilateral exports (see:

https://unctad.org/news/maritime-connectivity-countries-vie-positions).

26

Figure 8 – Changes in the number of direct connections per world region

(excluding intra-regional services) – Q4 2022 vs Q4 2019

Note: The number of countries directly connected has declined by approximately 5% in Q4 2022 compared

to Q4 2019; the capacity lost due to this reduction accounted for some 4% of the total capacity scheduled in

Q4 2019.

Source: MDS Transmodal, Container Shipping Market Quarterly Review, Q4 2022 – March 2023

In terms of service performance, the reliability and consistency of services significantly

degraded in the second half of 2020 until the second half of 2022. Despite gradual

improvements, at the end of 2022, they were still significantly below 2019 levels (see

Figure 9).

Figure 9 – Global liner shipping service performance – Index Q1 2019 = 100

Source: MDS Transmodal, Container Shipping Market Quarterly Review, Q4 2022 – March 2023

27

4. EVALUATION FINDINGS (ANALYTICAL PART)

4.1. To what extent was the intervention successful and why?

The question of the success of the CBER requires an assessment of whether it has (i)

brought legal certainty to carriers (section 4.1.1); (ii) simplified administrative

supervision of the sector (section 4.1.2); (iii) remained coherent with EU and

international rules (section 4.1.3); and (iv) facilitated the creation and operation of pro-

competitive consortia (section 4.1.4). Conclusion on whether, overall, the CBER

promoted competition is then drawn (section 4.1.5).

4.1.1. Legal certainty

Carriers, in particular large carriers,

78

consider that the findings in the 2019 evaluation

report as to the legal certainty brought by the CBER still hold true. They reiterate that it

contributes to legal clarity by providing more specific and concrete guidance than general

instruments of competition law and raises levels of compliance by leaving less space for

misinterpretation of the rules.

Nevertheless, those carriers do not substantiate their claim about the alleged insufficiency

of the horizontal guidance that will still be available to them without the CBER, in

particular the Horizontal Guidelines on joint production agreements and sustainability

agreements, the Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation and the Article 101(3)

Guidelines.

79

78

The carriers that expressed their views as to the legal certainty brought by the CBER are mainly large

carriers belonging to the three global alliances. It appears that smaller carriers having replied to the

targeted questionnaire were not in a position to provide informed views as to the legal certainty

brought by the CBER. This is because smaller carriers indicated that either they did not assess

compliance of any of their consortia with EU competition law over the evaluation period, or if they

did, they used the CBER for mere guidance due to non-compliance with the 30% maximum market

share condition.

79

At the time of the consultation activities for the evaluation of the CBER, the Horizontal Guidelines and

the Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation were under review. The new versions were published

in the Official Journal on, respectively, 21 July 2023 (OJ C 259/1) and 2 June 2023 (OJ L 243/20) and

could not, therefore, be used by carriers to maintain or amend their original claims about their lower

effectiveness compared to the CBER. The World Shipping Council nevertheless provided arguments

on that matter using the draft new versions used for the public consultation (https://competition-

policy.ec.europa.eu/public-consultations/2022-hbers_en). The World Shipping Council notably raised

the issue of the applicability of the Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation to consortia services

(or more generally to jointly operated services) based on the draft new version. It is noted that the final

version of the new Specialisation Block Exemption Regulation (as published on 2 June 2023) gives, as

an example of joint preparation of services, “cooperation in the creation or operation of a platform

through which a service will be provided” (recital (6)). The reference to the joint operation of assets

through which a service is provided indicates that consortia are a form of joint production agreement

that may be block-exempted if they fulfil the conditions set out in the revised Specialisation Block

Exemption Regulation.

In this document, further references to the Horizontal Guidelines and the Specialisation Block

Exemption Regulation should be understood as encompassing provisions applicable at the time of the

28

To the contrary, carriers’ responses to the fact-finding questionnaires sent in December

2021

80

tend to demonstrate an incomplete or inconsistent understanding of the substantive

provisions of the CBER, in particular of (i) the types of agreements that fall within the

definition of consortia and should be taken into account in the calculation of market

shares; (ii) the market(s) relevant for the calculation of the market share(s); (iii) the

application, to consortia serving more than one trade, of the conditions for exemption

relating to market share; and (iv) the need to be able to demonstrate compliance with the

conditions set out in the CBER.

Regarding point (i), while there is consensus among carriers that highly integrated

cooperation arrangements, such as vessel-sharing agreements and alliances, are consortia,

carriers voice uncertainty as to the correct treatment of more flexible cooperation

arrangements, such as slot charter and slot exchange agreements. For example, some

carriers consider stand-alone, non-reciprocal slot charter agreements as consortia