Revised 12/2017

The New York State

Dignity for All Students Act:

A Resource and Promising Practices

Guide for School Administrators &

Faculty

Education Law, Article 2: The legislature

finds that students’ ability to learn and

to meet high standards, and a school’s

ability to educate its students, are

compromised by incidents of

discrimination or harassment, including

bullying, taunting or intimidation. It is

hereby declared to be the policy of the

state to afford all students in public

schools an environment free of

discrimination and harassment. The

purpose of this article is to foster civility

in public schools and to prevent and

prohibit conduct which is inconsistent

with a school’s educational mission.

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface 3

Introduction 5

Section I School Climate and Culture 7

Section II Creating an Inclusive School Community: 16

Sensitivity to the Experience of Specific Student Populations

Section III School Personnel including, Supervisors and Principals 27

Section IV The Dignity Act Coordinator 32

Section V Family and Parent Engagement: Communicating with the School Community 35

Section VI Restorative Approaches and Progressive Discipline 37

Section VII Internet Safety and Acceptable Use Policies 45

Section VIII Guidance on Bullying and Cyberbullying 46

_________________________________________________________________

Appendix A Dignity for All Students Act (Dignity Act) 51

Glossary and Acronym Guide

Appendix B Federal Law Requiring Nondiscrimination Policies 61

3

Appendix C Selected Resources to Assist in the Implementation 62

of the Dignity Act

Appendix D Selected Resources Consulted 83

Appendix E Dignity Act Task Force Members 84

4

PREFACE

The New York State Dignity for All Students Act (Dignity Act): A Resource and Promising

Practices Guide for School Administrators and Faculty was developed by the Dignity Act Task

Force to assist schools in implementing the Dignity for All Students Act.

The Dignity Act added Article 2 to the Education Law (Education Law §§10 through 18). These

provisions took effect on July 1, 2012. In June 2012, the Legislature enacted Chapter 102 of the

Laws of 2012, which amended the Dignity Act, effective July 1, 2013, to, among other things,

include cyberbullying as part of the definition of “harassment and bullying” (Education Law §11[7],

[8]) and require instruction in safe, responsible use of the Internet and electronic communications

(Education Law §801-a). Chapter 102 also included a requirement that school professionals

applying for a certificate or license on or after July 1, 2013 complete training on the social patterns

of harassment, bullying and discrimination. However, this timeframe was extended until

December 31, 2013 pursuant to Chapter 90 of the Laws of 2013 (Education Law

§14[5]).

1

This resource guide, originally released in 2012, has been updated to reflect these amendments

to the Dignity Act. In using this guide, it is important to distinguish between legal requirements

and/or recommended practices. It is also important that communications be consistent in the use

of terms and concepts. An absence of such consistency can lead to misinformation and confusion

which does not advance the purpose of the Dignity Act.

This resource guide includes links to web sites that contain information, resources, and tools to

assist in the implementation of the Dignity Act in your school. Please evaluate each resource to

determine if it is developmentally age appropriate for your school population. The State Education

Department and the Dignity Act Task Force do not endorse any particular programs. The intent

of this document is to provide information only. School districts, charter schools, and BOCES

should consult with their school attorneys regarding specific legal questions. Analyses of

examples and hypothetical situations contained herein do not represent official determination(s)

or interpretation(s) by the Department. Scenarios described in this Guide may be the subject of

an appeal to the Commissioner of Education under section 310 of the Education Law; as a result,

the information contained herein is advisory only and does not necessarily represent the official

legal interpretation of the State Education Department.

The Dignity Act states that it is the policy of the State of New York to afford all students in public

schools an environment free of discrimination and harassment (Education Law §10). Educators

are encouraged to incorporate into core subject areas the principles embodied by the Dignity Act:

that no student shall be subject to harassment or bullying by employees or students on school

property or at a school function; nor shall any student be subjected to discrimination based on a

1

Detailed information on New York State’s requirements for certification as a teacher or other educational

professional may be found on the Office of Teaching Initiatives web site at:

http://www.highered.nysed.gov/tcert.

5

person’s actual or perceived: race, color, weight, national origin, ethnic group, religion, religious

practice, disability, sexual orientation, gender (including gender identity or expression), or sex.

To promote civility in public schools, and to prevent and prohibit conduct which is inconsistent

with a school's educational mission, the Dignity Act requires every school district in New York

State to include an age appropriate version of the State policy in its Code of Conduct (Education

Law §12[2]).

Schools are encouraged to use the resources in this guide to assist in augmenting or developing

programs and lessons. In addition, any core subject area can incorporate Dignity Act principles

into a lesson. Examples of this strategy may include the following:

If you are teaching students about the food chain in science class, add questions that ask the

students to compare the social environment at school to the food chain. Questions could be

focused on roles of various groups in school culture, interactions between those groups,

respect and roles of each group in the social structure, and respect of diversity within the

school culture.

You may also have students study great leaders, in whatever subject you teach, who were

maligned and shunned for being different or ahead of their time. Their life stories may inspire

students and help to introduce discussion topics.

The following resources may serve as a foundation in developing a comprehensive Dignity Act

program in your school:

Educating the Whole Child Engaging the Whole School: Guidelines and Resources for

Social and Emotional Development and Learning (SEDL) in New York State

www.p12.nysed.gov/sss/sedl/SEDLguidelines.pdf

This guidance document aims to give New York State school communities a rationale and the

confidence to address child and adolescent affective development as well as cognitive

development. By attending to social-emotional factors that may affect students’ brain

development and creating conditions where school environments are safe and supportive,

teachers can teach more effectively, students can learn better, and parents and the

community can feel pride in a shared enterprise. The guidelines and accompanying resources

seek to persuade school leaders, faculties, planning teams and parents that social and

emotional development and learning can be achieved through a range of approaches that

serve as entry points and avenues for expansion.

U.S. Department of Education Office of Safe and Healthy Students

http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oese/oshs/index.html

The federal Office of Safe and Healthy Students provide resources to school districts to

implement programs and services to prevent violence in schools, as well as drug and

substance abuse. Information on this page is directly related to the requirements and

6

provisions of the Act and is especially suited for administrators and others interested in

understanding these requirements. This includes resources related to anti-bullying and

positive school environment resources.

7

INTRODUCTION

The Dignity for All Students Act

In enacting the Dignity Act in 2010, the Legislature found that “a student’s ability to learn

and to meet high academic standards, and a school's ability to educate its students are

compromised by incidents of discrimination or harassment including bullying, taunting or

intimidation” (Education Law §10). In support of Chapter 102 of the Laws of 2012, the

legislative findings and intent included the following: “The legislature finds it is vital to

protect all students from harassment, bullying, cyberbullying, and discrimination. In

expanding the provisions of the Dignity for All Students Act, the legislature intends to give

school districts tools to address these harmful acts consistent with the emerging research

in the field. Bullying, harassment, and discrimination pose a serious threat to all students,

including but not limited to students targeted because of actual of perceived race, color,

weight, national origin, ethnic group, religion, religious practice, disability, sexual

orientation, gender, or sex. It is imperative to protect every student from such harm

regardless of whether the student is a member of a specific category.”

2

The Dignity Act prohibits acts of harassment and bullying, including cyberbullying, and/or

discrimination, by employees or students on school property or at a school function,

including but not limited to such conduct those based on a student’s actual or perceived

race, color, weight, national origin, ethnic group, religion, religious practice, disability,

sexual orientation, gender (defined to include gender identity or expression), or sex

(Education Law §12[1]). Cyberbullying is defined as harassment or bullying which takes

place through any form of electronic communication (Education Law §11[8]).

Schools may want to consider whether using the label “bully” is the most effective way to

address an individual’s behavior. It is important to note that the same child, in different

circumstances, may take the role of the bully, the target, or a bystander. Labels do not

reflect the range of roles a student may play. In addition, while a student may not readily

admit to being a “bully,” they may acknowledge engaging in harmful behavior toward

another student. When addressing inappropriate behavior, schools should carefully

consider using language that encourages the most productive and beneficial conversation

with students, staff, and persons in parental relation about what it means to treat others

with dignity and respect.

A key principle in the Dignity Act relates to reporting incidents of harassment, bullying,

and/or discrimination. Pursuant to §100.2(kk) of the Commissioner’s regulations, when

an incident is reported and an investigation verifies that a material incident of

harassment, bullying, and/or discrimination has occurred, the superintendent,

principal or designee shall take prompt action consistent with the district’s Code of

Conduct, reasonably calculated to end the harassment, bullying, and/or discrimination,

eliminate any hostile environment, create a more positive school culture and climate,

2

Chapter 102 of the Laws of 2012, section 1.

8

prevent recurrence of the behavior, and ensure the safety of the student(s) against whom

such behavior was directed (8 NYCRR §100.2[kk][2][iv]). The Commissioner’s

regulations define material incidents of harassment, bullying, and/or discrimination to

include:

“a single verified incident or a series of related verified incidents where a student

is subjected to harassment, bullying, and/or discrimination by a student and/or

employee on school property or at a school function. The term also includes a

verified incident of series of related incidents of harassment or bullying that occur

off school property (where such acts create or would foreseeably create a risk of

substantial disruption within the school environment, where it is foreseeable that

the conduct, threats, intimidation or abuse might reach school property) and is the

subject of a written or oral complaint to the superintendent, principal, or their

designee or other school employee” (8 NYCRR §100.2[kk][1][ix]).

Included in the Dignity Act is the prohibition of “cyberbullying,” which is defined as

harassment or bullying which occurs through any form of electronic communication

(Education law §11[8]). The regulation of harassment in the form of cyberbullying may

involve free speech, including constitutional matters regarding the ability of a school

district, BOCES, or charter school to restrict these forms of speech and expression and

to discipline individuals for engaging in them (see e.g. Tinker v. Des Moines Indep.

Community Sch. Dist., 393 US 503 [1969]). This issue will be addressed in Section VII

of this document; however, it is critical to note that although discipline may not always be

a viable option, the school is not precluded from taking actions that support and educate

the students involved in cyberbullying.

SECTION I: SCHOOL CLIMATE AND CULTURE

Establishing and sustaining a school environment free of harassment, bullying, and

discrimination should involve an examination of a school’s climate and culture. School

climate and culture have a profound impact on student achievement, behavior, and

reflects the school community’s culture.

School climate may be defined as the quality and character of school life. It may be based

on patterns of student, parent, and school personnel experiences within the school and

reflects norms, goals, values, interpersonal relationships, teaching and learning practices,

and organizational structures.

Key factors impacting school climate may include, but are not limited to, a person’s

perception of their personal safety, interpersonal relationships, teaching, learning, as well

as the external environment (www.schoolclimate.org/climate). The U.S. Department of

Education Office of Safe and Healthy Students (http://safesupportiveschools.ed.gov)

Safe and Supportive Schools Model emphasizes the core areas of

student/staff/community engagement, safety, physical environment, as well as emotional

environment.

9

A school’s culture is largely determined by the values, shared beliefs, and behavior of all

the various stakeholders within the school community and reflects the school’s social

norms.

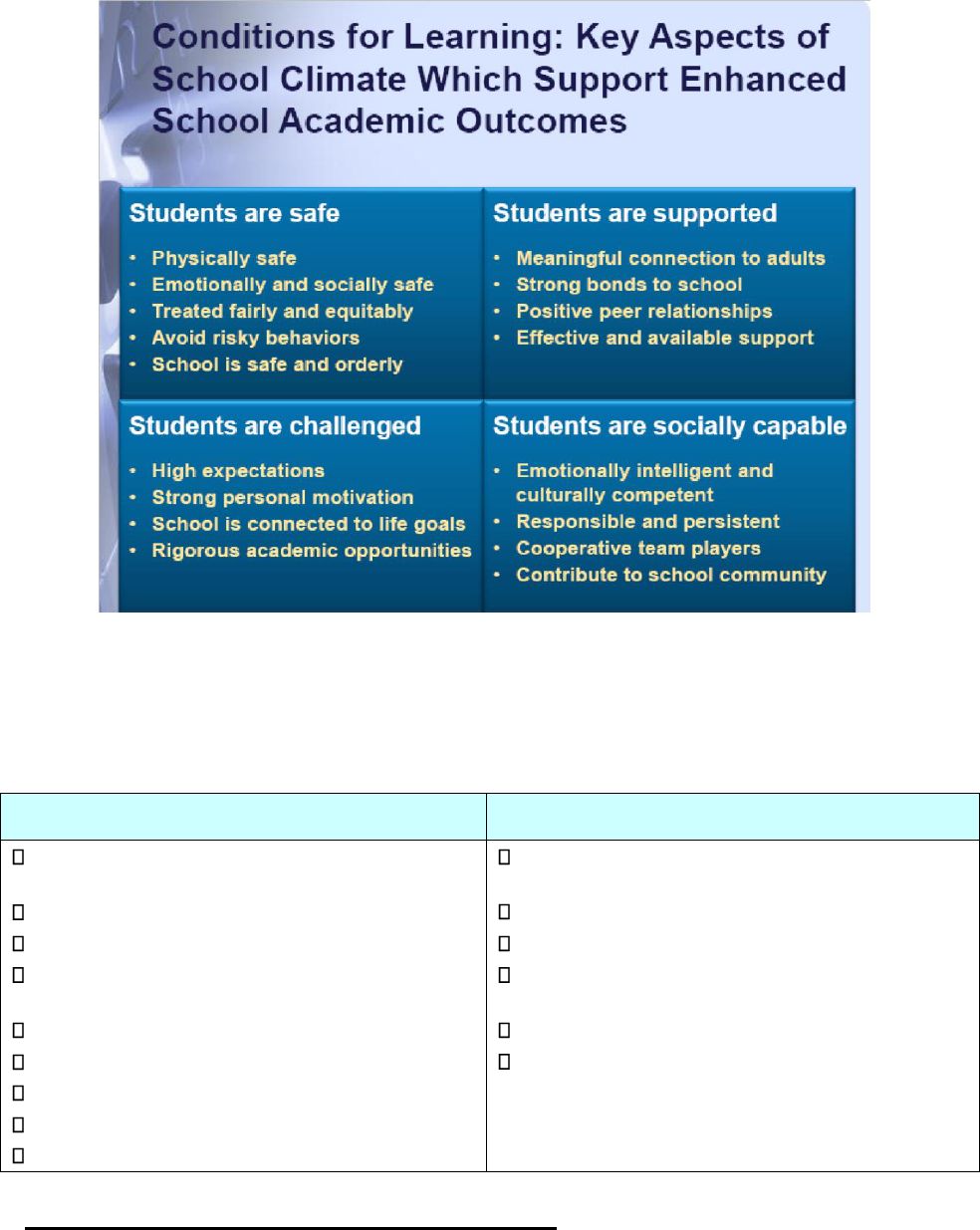

A presentation developed by Dr. David Osher and Dr. Chris Boccanfuso for the U.S.

Department of Education Safe and Supportive School Technical Assistance Center

further demonstrates the interconnectedness of enhanced academic outcomes and a

school climate where students feel safe, supported, academically challenged, and socially

capable. See:

http://safesupportiveschools.ed.gov/reader.php?upload=/20110303_PresentationFinal210

11SSSTASchoolClimateWebinarpublic.pdf

10

The following provides a guide to identifying the key stakeholders in a school – as it

directly relates to school climate and culture.

Who is the School Community?

Factors Impacting School Culture

Students and their families, including persons

in parental relation

Teachers

Administrators

Counselors, social workers, school nurses,

parent coordinators, PTA members

Related service providers

School safety personnel and resource

officers

Cafeteria, custodial, and other support staff

Transportation staff

Community organizations

Staff expectations of student behavior and

academic achievement

School policies and procedures

Consistent and equitable treatment of all

students Equity in, and access to, resources

(budget, space, time, personnel, supplies,

equipment) Equity in, and access to, support

services

Student and family engagement

SCHOOL CLIMATE AND CODES OF CONDUCT

Establishing behavioral expectations for students, staff, and visitors that encourage a

positive and respectful school climate and culture are essential to creating and

maintaining a safe and supportive school community.

11

Commissioner’s regulation §100.2(l)(2)(ii)(b) reflects the Dignity Act’s requirement that

boards of education create policies, procedures and guidelines intended to create a

school environment that is free from harassment, bullying and discrimination (see

Education Law §13).

See: www.regents.nysed.gov/meetings/2012Meetings/March2012/312p12a4.pdf

A WHOLE SCHOOL APPROACH – BUILDING STUDENT READINESS

There is an expectation that schools promote a positive school culture that encourages

interpersonal and inter-group respect among students and between students and staff.

To ensure that schools provide all students with a supportive and safe environment in

which to grow and thrive academically and socially, each of the following facets of a school

community must be considered:

Social Environment

• Interpersonal Relations: Students & Staff

• Respect for Diversity

• Emotional Well Being and Sense of Safety

• Student Engagement

• School & Family Collaboration

• Community Partnerships

Physical Environment

• Building Conditions

• Physical Safety

• School Wide Protocols

• Classroom Management

Behavioral Environment,

Expectations &

Supports

• Physical & Mental Well Being

• Prevention & Intervention Services

• Behavioral Accountability

(Disciplinary and Interventional

Responses)

The periodic review of a school’s social, physical, and behavioral environments, as well

as student and staff expectations and supports enable school leaders and personnel to

play a key role in establishing and sustaining school norms that foster a positive culture

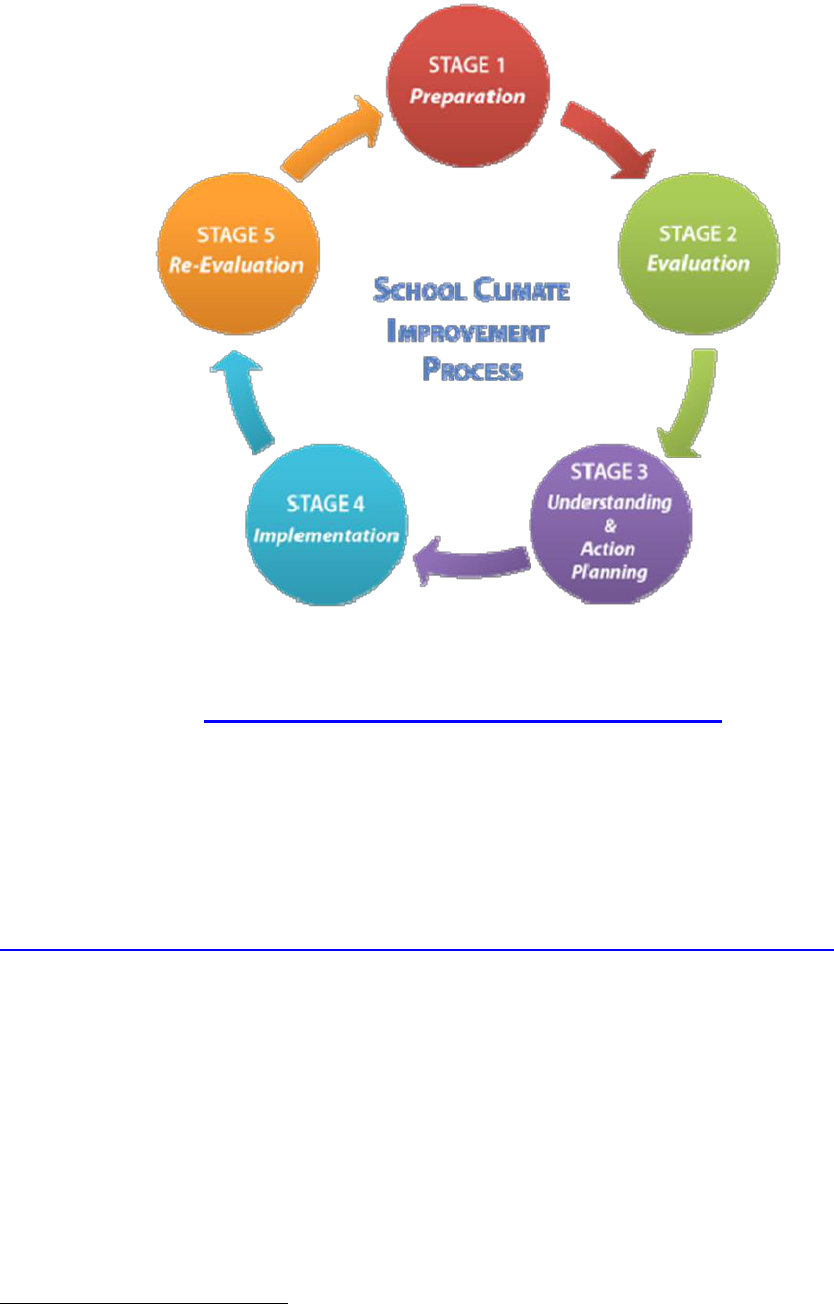

and climate in which all students can thrive. There are varying school climate models that

have been developed by organizations, as well as by other states. Many of these models

can be accessed through the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Safe and

Supportive Schools at http://safesupportiveschools.ed.gov. The National School Climate

Center, an organization dedicated to helping schools incorporate social and emotional

learning with academic instruction, has developed a school climate improvement model

based on a cyclical process of preparation, evaluation, understanding the evaluation

findings and action planning, implementing the action plan, and re-evaluation and

continuing the cycle of improvement efforts. This process enhances student

performance; reduces dropout rates, violence, bullying; while developing healthy and

positively engaged adults. (http://schoolclimate.org/climate/process.php)

SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING

12

The State Board of Regents affirmed support for social and emotional learning on July 18,

2011 by formally adopting Educating the Whole Child – Engaging the Whole School:

Guidelines and Resources for Social and Emotional Development and Learning (SEDL)

in New York State www.p12.nysed.gov/sss/sedl/SEDLguidelines.pdf.

In the summary presented to the Board of Regents by State Education Commissioner

John B. King, Jr., it was noted that “social and emotional development is the ability to

understand, manage, and express the social and emotional aspects of one’s life in ways

that enable the successful management of life tasks such as learning, forming

relationships, solving everyday problems, and adapting to the complex demands of

growth and development.”

3

www.regents.nysed.gov/meetings/2011Meetings/July2011/711p12a6-revised.pdf

Teaching social and emotional skills is as important as teaching academic skills. Abraham

Maslow’s statement, “If you only have a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a

nail,” speaks directly to the fundamental need to provide students with instruction in

social/emotional skills as both an overarching prevention strategy and as a primary

intervention strategy for children whose “toolkit” of responses needs to be expanded to

include appropriate, pro-social strategies for effectively interacting with others.

Schools are encouraged to address prevention and intervention on three levels (Lewis &

Sugai 1999; Sugai et al 2000, Walker et al 1996):

3

Elias, M., Zins, J., Weissberg, P., Frey, K., Haynes, N., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M., Shriver, T.,

(1997) Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

13

• Primary (universal) prevention to promote pro-social development and prevent problems

• Secondary prevention to address the needs of at-risk students as soon as possible when

behavioral incidents occur

• Tertiary prevention that provides applicable interventions to students with chronic and/or

severe problems.

www.p12.nysed.gov/sss/sedl/SEDLguidelines.pdf

Prevention and intervention continuum to promote healthy, adaptive and pro-social

behaviors (Walker et al 1996)

Some Guiding Questions to Consider When Examining These Factors

How well does the school project a welcoming

How are students learning empathy?

and supportive environment for all students?

How often does the school review, and amend,

What are the school’s behavioral expectations

its safety and security procedures to ensure that

for students and staff, and how well do they

all areas to which students have access are well

address the responsibility of the school to

monitored and supervised, including stairwells,

ensure a safe and supportive environment?

hallways, locker rooms and athletic facilities,

How does the school communicate its clear

outside play areas, cafeteria, auditorium, etc.

expectations regarding pro-social behavior

When students do not meet behavioral

and respect within the school community with

expectations, how does the school ensure

staff and students?

equitable access to support and disciplinary

How well do all adult members of the school

accountability?

community model respect for diversity in their

When disciplinary data is regularly reviewed, how

interactions with one another – and with

does the school bring multiple perspectives and

students and their families?

disciplines to the process?

What kinds of programs and initiatives does

How are resources used to support student

the school implement to promote respect for

engagement (student organizations, clubs and

14

diversity?

teams) so that all students see themselves as

If an individual or group engages in

valued members of the school community?

discriminatory behavior toward a student or

How does the school actively support and

group of students based on the student’s or

encourage diversity in student government?

group of students’ actual or perceived identity,

how does the school address the behavior so

that it does not become a pervasive or

persistent pattern and so that the individual

student or group of students does not have

reason to believe that such behavior is likely

to continue?

How does the school provide regularly scheduled

opportunities for students, especially those who

are not elected to student government, to share

ideas, identify concerns and strategies for

improved school climate and culture with the

principal/school leaders?

How does the school integrate respect for

diversity into the curriculum?

How well does the school promote diversity in the

recruitment and training of students who serve as

peer mediators in the school’s peer

How well does the school library collection

mediation center?

(books, periodicals, multimedia resources)

and visual displays throughout the building

promote respect for diversity?

How successful is the school in welcoming the

families of all students into the school

community?

Are library collections readily accessible to

everyone in the school?

Does the school engage and encourage parents

to work as partners in their children’s learning?

How are students, the largest group of

stakeholders in the school community,

involved in preventing bias-based behavior

and promoting respect?

How does the school celebrate and recognize

students’ successes, progress and achievement

so that all students see themselves as valued

members of the school community?

How are students provided with opportunities

for social emotional learning?

Social and emotional learning helps students develop fundamental and effective life skills,

including: recognizing and managing emotions; developing caring and concern for others;

establishing positive relationships; making responsible decisions; and handling

challenging situations constructively and ethically. Such skills help prevent negative

behaviors and the disciplinary consequences that may result when students do not live

up to behavioral standards.

A strictly punitive or reactive approach to inappropriate student behavior is neither the

intent of the Dignity Act, nor has it been proven effective in reducing incidents. Rather it

is recommended that strategies such as prevention, intervention,

and graduated/progressive discipline be considered in addressing and correcting

inappropriate behavior, while re-enforcing pro-social values among students.

Student Engagement

Students are the largest group of stakeholders in the school and its greatest resource in

creating and sustaining a safe and supportive school environment. Student engagement

is essential in creating a positive school culture and climate that effectively fosters student

academic achievement and social/emotional growth. The quality of student life and the

15

level of student engagement may be the best single indicator of potential or current school

safety and security concerns as they pertain to student behavior.

Providing students with multiple opportunities to participate in a wide range of pro-social

activities and, at the same time, bond with caring, supportive adults mitigates against

negative behaviors are key to promoting a safe and supportive school. Such

opportunities, coupled with a comprehensive guidance program of prevention and

intervention, provide students with the experiences, strategies and skills, and support they

need to thrive.

Student and staff access to school library and classroom materials which address human

relations in the areas of race, color, weight, national origin, ethnic group, religion, religious

practice, disability, sexual orientation, gender (including gender identity or expression), or

sex may also promote an environment in which social/emotional growth can be nurtured

and thrive.

General resources to assist school administrators, teachers, and the Dignity Act

Coordinator in addressing the needs of students are in Appendix C of this guide.

Student Empowerment

The Dignity Act states that “[n]o student shall be subjected to harassment or bullying by

employees or students on school property or at a school function; nor shall any student

be subjected to discrimination based on a person’s actual or perceived race, color, weight,

national origin, ethnic group, religion, religious practice, disability, sexual orientation,

gender, or sex by school employees or students on school property or at a school

function…” (Education Law §12[1]).

Whether a student is being bullied himself/herself or has witnessed another student being

bullied, s/he needs to feel empowered, comfortable, and safe reporting such an incident

to school faculty or staff. Specifically, the Dignity Act requires that boards of education

create policies, procedures and guidelines that enable students and parents to make oral

and/or written reports of harassment, bullying or discrimination to teachers,

administrators, and other school personnel that the school district deems appropriate

(Education Law §13[1][b]).

Even with such policies in place, a student who has been bullied may still hesitate in

seeking help from an adult. Since the Dignity Act applies to both student-to-student and

faculty/staff-to-student behavior, it is important to keep in mind that the student may have

been harassed or bullied by a school employee. In a case such as this, the issues of

empowerment and trust are that much more critical – and the objectivity and

approachability of the person the student confides in is essential.

The U.S. Department of Education has developed an on-line toolkit designed to assist

educators in addressing issues related to incidents of bullying by Creating a Safe and

Respectful Environment in Our Nation’s Classrooms. This program points out that

16

students may not report bullying due to a variety of reasons ranging from the humiliation

they already feel from having been bullied and the fear that reporting the behavior will

only worsen this, to feelings of isolation and a belief that no adult will believe and/or help

them address the situation.

See: (http://safesupportiveschools.ed.gov/index.php?id=1480).

To assist students who may be bullied, the Dignity Act includes a requirement that boards

of education create policies, procedures and guidelines that require each school to

provide all students, school employees, and parents with an electronic or written copy of

the district’s Dignity Act policies, including notification of the process by which they may

report harassment, bullying, and discrimination (Education Law §13[1][k]).

School and District Practice and Policies

A school’s culture may be the single most important factor in preventing, limiting, and/or

dealing with bullying and cyberbullying incidents. Educators need to work diligently to

create school cultures that value and teach respect for all. The most positive school

cultures are culturally sensitive and model positive behavioral interactions.

Potential strategies available to create a comprehensive response to bullying and

cyberbullying include policies and programs that address school climate; Code of

Conduct; Internet Safety and Accepted Use Policies which comply with the federal

Children’s Internet Protection Act; and the analysis of Violent and Disruptive Incident

Reports (VADIR).

• School culture: NYSED, in conjunction with the New York State Office of Mental

Health, has developed Guidelines and Resources for Social and Emotional

Development and Learning (SEDL) in New York State. This document, and other

SEDL resources to assist schools in developing positive school climates and cultures,

can be found at www.p12.nysed.gov/sss/sedl/.

• Code of Conduct: All public school districts must adopt and provide for the

enforcement of a written Code of Conduct for the maintenance of order on school

property and at school functions. The Code of Conduct must govern the conduct of

students, teachers, other school personnel and visitors (see Education Law §2801[2]

and Commissioner’s Regulation 8 NYCRR §100.2[l][2][i]).

For specific information on Dignity Act Amendments affecting the Code of Conduct

see “Guidance for Updating Codes of Conduct” at:

http://www.p12.nysed.gov/dignityact/documents/DASACodeofConductGuidance.pdf

An age-appropriate summary of the Code of Conduct must be provided to all students

at a school assembly at the beginning of each school year; a plain language summary

of the Code of Conduct must be mailed to all persons in parental relation to students

before the beginning of each school year; each teacher must be provided with a copy

of the complete code of conduct and a copy of any amendments as soon as

practicable following initial adoption or amendment of the code; and each new teacher

17

must be provided with a complete copy of the current code upon their employment

(see Education Law §2801[4]; 8 NYCRR

§100.2[l][2][iii][b]). This also provides an opportunity for school personnel to both

review the Code of Conduct with students and parents and identify possible gaps in

policy, practices, and procedures.

The Code of Conduct must be reviewed annually and updated if necessary, taking into

consideration the effectiveness of code provisions and the fairness and consistency

of its administration (see Education Law §2801[5][a] and 8 NYCRR §100.2[l][2][iii][a]).

This annual review provides an opportunity to assess whether the Code of Conduct

needs to be revised to address, among other things, the use of new forms of

technology on school grounds and/or at school functions by students, teachers, other

school personnel and visitors. A district may establish a committee to facilitate the

review of its Code of Conduct and the district’s response to Code of Conduct violations

(see Education Law §2801[5][a] and 8 NYCRR §100.2[l][2][iii][a]). The review

team/committee must include student, teacher, administrator, and parent

organizations, school safety personnel and other school personnel (Education Law

§2801[5][a] and 8 NYCRR §100.2[l][2][iii][a]). Such committee might also include

school staff, community members, and law enforcement officials. It is also

recommended that individuals with strong technology skills and a thorough

understanding of how students, teachers, and staff are using technology be recruited

to assist in the review of the Code of Conduct. This will help ensure that the Code of

Conduct reflects current and anticipated challenges that have been created or are

anticipated through the evolution of technology. In addition, prior to board adoption of

the updated code of conduct a public hearing must be held to inform the community

about the proposed changes and receive input.

The Code of Conduct is an ideal document in which to establish expectations and

consequences for student and staff conduct regarding internet safety and the use of

technology while on school grounds and/or at school functions. Teachers must be

provided with a complete copy of the Code of Conduct (8 NYCRR §100.2[l][2][iii][b][4])

and complete copies of the Code of Conduct must also be made available for review

by students, persons in parental relation to students, and other community members

(see Education Law §2801[4] and 8 NYCRR §100.2[l][2][iii][b]). The complete Code

of Conduct, including any annual updates or other amendments, must be posted on

the school district’s website, if one exists (8 NYCRR

§100.2[l][2][iii][b][1]).

SECTION II: CREATING AN INCLUSIVE SCHOOL COMMUNITY: SENSITIVITY TO

THE EXPERIENCE OF SPECIFIC STUDENT POPULATIONS

Every student deserves to learn in a safe and supportive school. Unfortunately,

experience and research has shown that some groups of students are more vulnerable

to discrimination and harassment, including bullying behavior, than others. Therefore, it

is vital that school staff be especially attentive regarding their welfare and safety.

18

Children with Special Needs

A growing body of research has demonstrated that children with special needs are at an

increased risk of being bullied. Bullying Among Children and Youth with Disabilities and

Special Needs, a fact sheet from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

(www.stopbullying.gov) provides the following insights into the vulnerability of these

children:

• Available information indicates that children with learning disabilities are at greater risk

of being teased and physically bullied (Martlew & Hodson, 1991; Mishna, 2003;

Nabuzoka & Smith, 1993; Thompson, Whitney, & Smith, 1994).

• Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are more likely than

other children to be bullied. They also are somewhat more likely than others to bully

their peers (Unnever & Cornell, 2003).

• Children with medical conditions that affect their appearance (e.g., cerebral palsy,

muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida) are more likely to be victimized by peers.

Frequently, these children report being called names related to their disability

(Dawkins, 1996).

Walk A Mile in Their Shoes: Bullying and the Child with Special Needs

4

, a report and

guide compiled by www.AbilityPath.org, addresses the issue of children with special

needs being targets of harassing behavior: The report and guide includes the following

research findings:

• Researchers have discovered that students with disabilities were more worried about

school safety and being injured or harassed by peers, compared to students without

a disability (Saylor & Leach, 2009).

• According to researchers Wall, Wheaton and Zuver (2009) only 10 studies have been

conducted in the United States on bullying and developmental disabilities. All studies

found that children with disabilities were two to three times more likely to be victims of

bullying than their non-disabled peers. In addition, the researchers found that the

bullying experienced by these children was more chronic in nature and was most often

directly related to their disability.

“Disability harassment” is illegal under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and

Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. According to the U.S. Department

of Education, disability harassment is “intimidation or abusive behavior toward a student

based on disability that creates a hostile environment by interfering with or denying a

student’s participation in or receipt of benefits, services, or opportunities in the institution’s

program” (U.S. Department of Education, 2000).

4

www.abilitypath.org/areas-of-development/learning--schools/bullying/articles/walk-a-mile-

intheir-shoes.pdf

19

Please see: http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/disabharassltr.html

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs)

The Interactive Autism Network (IAN) conducted a national study related to the frequency

of students with ASDs being bullied in school.

5

The initial results of the study released in 2012, illustrate that “children with ASD are

bullied at a very high rate, and are also often intentionally “triggered” into meltdowns or

aggressive outbursts by ill-intentioned peers.” The IAN further reported that “bullying is

extremely common in the lives of children with ASD, and occurs at a much higher rate for

them than it does for their typically developing siblings. It is crucial that educators,

providers, advocates, and families be aware of this, and be prepared to intervene.

Children with ASD are already vulnerable in multiple ways. To have to face teasing,

taunts, ostracism, or other forms of spite may make a child who is already struggling to

cope completely unable to function. If a child was anxious, or dealing with issues of self-

control, or unable to focus before there was any bullying, imagine how impossible those

issues must seem when bullying is added to the mix. Cruelest of all is the fact that bullying

may further impair the ability of a child with ASD, who is already socially disabled, to

engage with the social world.”

The following chart was developed as part of the IAN Report, is based on a survey of

parents of children (ages 6-15) with ASD. Parents were asked whether their child had

ever been bullied. Of the 1,167 students associated with this survey, 63% indicated that

they had been bullied at some point.

On the other hand, “children with ASD may also behave as bullies, or at least be viewed

as such. In fact, 20% of parents told us their child with ASD had bullied others, a rate that

5

www.iancommunity.org/cs/ian_research_reports/ian_research_report_bullying

20

compares to only 8% for typical siblings. Most of these children were bully-victims –

children who had been bullied and had also bullied others.”

Refugee and Immigrant Children

A refugee is a person who has left his or her country of nationality and is unable or

unwilling to return to that country due to persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution

based upon race, religion, nationality, membership in a specific social group, or political

group. New York State receives refugee children every year. While most come with some

family, others come alone, and all leave behind everything they have ever known. Some

refugee children have experienced the ravages of war and others have suffered trauma

because of their experiences in refugee camps.

Children who come to the United States as refugees face the challenge of adapting to a

new environment while coping with the loss of home, family members, friends,

belongings, and community. Although immigrant children usually do not leave their homes

under the same kinds of circumstances that compel refugees to flee their country of

nationality, they share some of the same challenges faced by refugee children in adapting

to a new environment, learning a new language and creating social support networks with

peers and adults in a new school community.

Both refugee and immigrant children must deal with vast cultural change, and cultural

misunderstandings can make them particularly vulnerable to harassment in the form of

bullying. Factors such as a lack of understanding of cultural norms, different expectations

for personal hygiene, peer pressure around appropriate clothing, different kinds of social

boundaries, different culturally informed gestures, body language and use of personal

space can make immigrant or refugee children the target of harassment.

•

A Brown University New England Equity Assistance Center (NEEAC) study in a

medium-sized Massachusetts school district found that twice as many middle school

English Language Learners (ELLs) reported worrying about being physically bullied

as compared to their non-ELL peers and 49% of ELL students reported that students

make fun of others with accents as compared to 21% of non-ELL students.

www.cga.ct.gov/coc/PDFs/bullying/102107_bullying_immigrants.pdf

To compound such issues, depending on the conditions in their home country, immigrant

children and refugee children may be mistrustful of authority and, therefore, reluctant to

report harassment or discrimination because they do not want to draw attention to

themselves. Bridging Refugee Youth and Children’s Services (BRYCS) provides national

technical assistance to organizations serving refugee and immigrants. Its website

www.brycs.org includes multiple resources that can assist educators in providing support

to immigrant and refugee children.

LGBTQ Children

6

6

It is recognized that there are several commonly used variants of this acronym. For the purposes

of consistency in this guidance document, the acronym LGBTQ will be officially used to refer to

21

The Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) reports that many lesbian,

gay, bisexual, and transgender teens in the United States experience homophobic

remarks and harassment throughout the school day, creating an atmosphere where they

feel disrespected, unwanted, and unsafe.

Homophobic remarks such as “that’s so gay” are the most commonly heard type of biased

remarks at school. GLSEN’s research has found that such slurs may be unintentional

since they may be part of teens’ vernacular. Despite this, most teens do not recognize

that the casual use of such language often carries over into more overt harassment. See:

www.thinkb4youspeak.com/ForEducators/?state=&type=antibullying.

Students who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning (LGBTQ) are often

reluctant to report harassment or discrimination. Negative attitudes that some people

have toward LGBT individuals in general put such youth at increased risk for experiences

with violence, compared with other students (Coker, Austin, Schuster, Annual Review of

Public Health 2010.) Such behaviors can include bullying, teasing, harassment, and

physical assault. GLSEN’s 2009 National School Climate Survey examined the responses

of 7,261 middle and high school students.

Key findings include:

• 84.6% of LGBT students reported being verbally harassed, 40.1% reported being

physically harassed and 18.8% reported being physically assaulted at school in the

past year because of their sexual orientation.

•

72.4% heard homophobic remarks, such as "faggot" or "dyke," frequently or often at

school.

•

Over three-fifths (61.1%) of students reported that they felt unsafe in school because

of their sexual orientation, and more than a third (39.9%) felt unsafe because of their

gender expression.

•

63.7% of LGBT students reported being verbally harassed, 27.2% reported being

physically harassed and 12.5% reported being physically assaulted at school in the

past year because of their gender expression.

See: www.glsen.org/binary-data/GLSEN_ATTACHMENTS/file/000/001/1675-2.pdf

"Playgrounds and Prejudice: Elementary School Climate in the United States," a study

published by GLSEN in January 2012 further revealed the following statistics:

• The most common forms of biased language in elementary schools, heard

regularly (i.e., sometimes, often or all the time) by both students and teachers, are

the use of the word "gay" in a negative way, such as "that's so gay," (students:

45%, teachers: 49%) and comments like "spaz" or "retard" (51% of students, 45%

of teachers). Many also report regularly hearing students make homophobic

individuals who self-identify as either lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning.

Variations of this acronym are taken from the original source material.

22

remarks, such as "fag" or "lesbo" (students: 26%, teachers: 26%) and negative

comments about race/ethnicity (students: 26%, teachers: 21%).

• Three-fourths of students (75%) report that students at their school are called

names, made fun of or bullied with at least some regularity. Most commonly this is

because of students' looks or body size (67%), followed by not being good at sports

(37%), how well they do at schoolwork (26%), not conforming to traditional gender

norms/roles (23%) or because other people think they're gay (21%).

www.glsen.org/cgi-bin/iowa/all/library/record/2832.html?state=research&type=research

A key finding in GLSEN’s "Playgrounds and Prejudice: Elementary School Climate in the

United States" study was the physical location where students reported being directly

confronted in name calling situations. Figure 3.7 “Locations Where Bullying or Name-

Calling Occurs at School” provides valuable insight for school administrators, the DAC(s),

and other personnel in relation to where to focus their efforts to curtail and ultimately

eliminate such acts. See:

www.glsen.org/binary-data/GLSEN_ATTACHMENTS/file/000/002/2027-1.pdf

Still another critical finding was the student’s perception of whether reporting such acts to

their teacher helped to resolve the situation. Figure 3.8 “Frequency and Helpfulness of

23

Telling a Teacher About Being Called Names, Made Fun Of, or Bullied at School” is

particularly significant since all students are entitled to attend school in a safe and

supportive environment free from bullying, discrimination, and harassment. See:

www.glsen.org/binary-data/GLSEN_ATTACHMENTS/file/000/002/2027-1.pdf

Additional research published in 2011 by the National Center for Transgender Equality

and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force revealed that students “…who expressed

a transgender identity or gender non-conformity while in grades K-12 reported alarming

rates of harassment (78%), physical assault (35%) and sexual violence (12%);

harassment was so severe that it led almost one-sixth (15%) to leave a school in K-12

settings or in higher education.” The research also found that individuals “…who have

been harassed and abused by teachers in K-12 settings showed dramatically worse

health and other outcomes than those who did not experience such abuse. Peer

harassment and abuse also had highly damaging effects.”

http://transequality.org/PDFs/NTDS_Report.pdf

According to GLSEN’s Harsh Realities report “Nearly nine in ten transgender students

have been verbally harassed in the last year due to their gender expression (87 percent)

and more than half have also been physically assaulted (53 percent).” In addition, the

report states “nearly half of transgender students report regularly skipping school because

of safety concerns, clearly impacting their ability to receive an education, and nearly one

in six (15 percent) of transgender and gender nonconforming students face harassment

so severe that they are forced to leave school.”

Finally, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that a survey

of more than 7,000 seventh and eighth grade students from a large Midwestern county

examined the effects of school climate and homophobic bullying on lesbian, gay, bisexual,

and questioning (LGBQ) youth and found that:

24

•

LGBQ youth were more likely than heterosexual youth to report high levels of

bullying and substance use.

•

Students who were questioning their sexual orientation reported more bullying,

homophobic victimization, unexcused absences from school, drug use, feelings

of depression, and suicidal behaviors than either heterosexual or LGBQ

students.

Children in Foster Care and Children with Incarcerated Parents

While bullying can be a common problem for all students, children in foster care and

children with incarcerated parents face additional stigmas that make them more

susceptible to being victims or bullies at school. These children frequently miss school,

which can lead to education and social problems, making them easy targets.

Furthermore, they may feel humiliated for having lost contact with their parents and may

worry about how their parents are doing or when they might see or talk to them again.

These worries can lead to anxiety, making the child stressed and emotionally

overwhelmed.

• More than 72% of incarcerated women report being parents.

• In New York, it is estimated that more than 105,000 minor children have a parent

serving time in prison or jail at any one time.

• There are more than 120,000 individuals subject to probation, and nearly 42,000

on parole as of December 31, 2009.

Source: www.osborneny.org/NYCIP/ACalltoActionNYCIP.Osborne2011.pdf A Call to Action:

Safeguarding New York’s Children of Incarcerated Parents A Report of the New York Initiative for

Children of Incarcerated Parents (May 2011)

Additionally, children in foster care and children with incarcerated parents may become

withdrawn and experience low self-esteem. Children may be afraid of the stigmas and

stereotypes that come with being a child in foster care or a child with an incarcerated

parent. For example, when it is known that a child has an incarcerated parent, s/he may

be blamed if another student’s personal belongings go missing based on the beliefs that

“the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree” and criminality is in the child’s genes.

Consequently, students may shy away from revealing their situation to school staff or their

peers and may inevitably cope with their struggles alone.

Children in foster care and children with incarcerated parents are also more likely to

become bullies. As a result of their situation, they may turn to anger, aggression, drugs

and/or alcohol as an outlet. Being unable to control their emotions, they may take out their

anger and frustration on fellow peers at school. According to the CDC, drug and alcohol

use, high emotional distress, and high level of family disruption are risks that may lead to

youth violence.

Home life can also be extremely difficult for these students. Placement in kinship foster

homes, while done in order to minimize change or disruption in their families, has the

possibility of making the living situation even more complicated. According to the 2011

Osborne Report, the Child Welfare League of America defines kinship caregivers as

“relatives, members of a tribe or clan, godparents, step-parents, or other adults who have

25

a kinship bond with a child.” Therefore, whatever emotions the child is experiencing the

kinship caregiver is probably feeling something very similar. While a kinship caregiver

may also have a better understanding of what the child is going through, it may be difficult

for the caregiver to separate his/her emotions from his/her interaction with the child.

In addressing the special needs of these populations, some model programs have been

developed. For example, in Virginia, public schools have implemented the Milk and

Cookies Children’s Program, a support-based group that allows children with incarcerated

parents to meet with peers in the same situation and talk amongst themselves with a

trained adult. The program is designed to help the children understand their situation and

how to react appropriately.

The federal McKinney-Vento Act provides specific protections to ensure educational

stability for students who are homeless or in temporary housing. Both McKinney-Vento

and the Dignity Act have raised awareness and sensitivity about particular issues that

may impact students’ education and the need to increase the educational outcomes for

children who attend public schools. McKinney-Vento has had a positive effect on the

educational opportunities, attendance and outcomes for students in temporary housing.

For more information on the McKinney-Vento Act, please see: http://nysteachs.org

www.p12.nysed.gov/nclb/programs/homeless or call 800-388-2014.

Federal Civil Rights Statues Related to Schools and Harassment

Schools that receive federal funding are required by federal law to address discrimination.

The statutes the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) enforces include:

• Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), which prohibits discrimination

on the basis of race, color, or national origin;

• Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Title IX), which prohibits

discrimination on the basis of sex, including sexual harassment and

stereotyping;

• Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504); and Title II of the

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (Title II). Section 504 and Title II prohibit

discrimination on the basis of disability.

Federal courts have found that school districts may be subject to liability in Title VI and

Title IX cases for teacher or peer harassment when the district exercises substantial

control over the harasser and the context in which the known harassment occurs, the

harassment is severe and discriminatory, the district has actual knowledge of the

harassment, and its response amounts to deliberate indifference to discrimination (see

e.g., Davis ex. rel. LaShonda P. v. Monroe Cnty. Bd. of Educ., 526 US 629 [1999]; Zeno

v. Pine Plains Central School District, 702 F3d 655 [2d Cir. 2012]).

US Department of Education Office of Civil Rights “Dear Colleague” Letter on

Harassment and Bullying

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights periodically issues “Dear

Colleague” letters to school districts and to schools on pertinent issues related to K-12

26

and higher education. The October 2010 “Dear Colleague” letter from U.S. Assistant

Secretary of Education Russlynn Ali addressed harassment and bullying and is

particularly pertinent to implementing the Dignity Act within the larger context of federal

civil rights laws.

The following are excerpts from the Office of Civil Rights’ letter:

(www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201010.pdf)

[S]ome student misconduct that falls under a school’s anti-bullying policy also may

trigger responsibilities under one or more of the federal civil antidiscrimination laws

enforced by [OCR]…. Harassing conduct may take many forms, including verbal acts

and name calling, graphic and written statements, which may include use of cell phones

or the Internet; or other conduct that may be physically threatening, harmful, or

humiliating. Harassment does not have to include intention to harm, or be directed

at a specific target, or involve repeated incidents.

Harassment creates a hostile environment when the conduct is sufficiently severe,

pervasive, or persistent to interfere with or limit a student’s ability to participate in or

benefit from the services, activities, or opportunities offered by a school. When such

harassment is based on race, color, national origin, sex, or disability, it violates the civil

rights laws that U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights enforces.

Some conduct alleged to be harassment may implicate the First Amendment rights to free

speech or expression. For more information on the First Amendment’s application to

harassment, see the discussions in OCR’s Dear Colleague Letter: First Amendment (July

28, 2003), available at www.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/firstamend.html)

As noted in the October 2010 U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights

letter, a school is responsible for addressing harassment incidents about which it

knows or reasonably should have known.

A school has notice of harassment if a responsible employee knew, or in the exercise of

reasonable care should have known, about the harassment. In some situations,

harassment may be in plain sight, widespread, or well-known to students and staff, such

as harassment occurring in hallways, during academic or physical education classes,

during extracurricular activities, at recess, on a school bus, or through graffiti in public

areas. In these cases, the obvious signs of the harassment are sufficient to put the school

on notice. In other situations, the school may become aware of misconduct, triggering an

investigation that could lead to the discovery of additional incidents that, taken together,

may constitute a hostile environment.

The following is an excerpt from the October 2010 letter from U.S. Assistant Secretary of

Education Russlynn Ali, available at:

www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201010.pdf.

27

In all cases, schools should have well-publicized policies prohibiting harassment and

procedures for reporting and resolving complaints that will alert the school to incidents of

harassment.

When responding to harassment, a school must take immediate and appropriate action

to investigate or otherwise determine what occurred. The specific steps in a school’s

investigation will vary depending upon the nature of the allegations, the source of the

complaint, the age of the student or students, involved, the size and administrative

structure of the school, and other factors. In all cases, however, the inquiry should be

prompt, thorough, and impartial.

If an investigation reveals that discriminatory harassment has occurred, a school must

take prompt and appropriate steps reasonably calculated to end the harassment,

eliminate any hostile environment and its effects, and prevent the harassment from

recurring. These duties are a school’s responsibility even if the misconduct is also

covered by an anti-bullying policy, regardless of whether a student has complained,

asked the school to take action, or identified the harassment as a form of discrimination.

Appropriate steps to end harassment may include separating the accused harasser and

the target, providing counseling for the target and/or harasser, or taking disciplinary action

against the harasser. These steps should not penalize the student who was harassed.

For example, any separation of the target from an alleged harasser should be designed

to minimize the burden on the target’s educational program (e.g., not requiring the target

to change his or her class schedule).

In addition, depending on the extent of the harassment, the school may need to provide

training or other interventions not only for the perpetrators, but also for the larger school

community, to ensure that all students, their families, and school staff can recognize

harassment if it recurs and know how to respond. A school also may be required to

provide additional services to the student who was harassed in order to address the

effects of the harassment, particularly if the school initially delays in responding or

responds inappropriately or inadequately to information about harassment. An effective

response also may need to include the issuance of new policies against harassment and

new procedures by which students, parents, and employees may report allegations of

harassment (or wide dissemination of existing policies and procedures), as well as wide

distribution of the contact information for the district’s Title IX and Section 504/Title II

coordinators.

28

Finally, a school should take steps to stop further harassment and prevent any retaliation

against the person who made the complaint (or was the subject of the harassment) or

against those who provided information as witnesses. At a minimum, the school’s

responsibilities include making sure that the harassed students and their families know

how to report any subsequent problems, conducting follow-up inquiries to see if there

have been any new incidents or any instances of retaliation, and responding promptly

and appropriately to address continuing or new problems.

When responding to incidents of misconduct, schools should keep in mind the following:

• The label used to describe an incident (e.g., bullying, hazing, teasing) does not

determine how a school is obligated to respond. Rather, the nature of the conduct

itself must be assessed for civil rights implications. So, for example, if the abusive

behavior is on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, or disability, and creates

a hostile environment, a school is obligated to respond in accordance with the

applicable federal civil rights statutes and regulations enforced by OCR.

• When the behavior implicates the civil rights laws, school administrators should

look beyond simply disciplining the perpetrators. While disciplining the

perpetrators is likely a necessary step, it often is insufficient. A school’s

responsibility is to eliminate the hostile environment created by the harassment,

address its effects, and take steps to ensure that harassment does not recur. Put

differently, the unique effects of discriminatory harassment may demand a

different response than would other types of bullying.

SECTION III: SCHOOL PERSONNEL INCLUDING SUPERINTENDENTS AND

PRINCIPALS

Harassment, Bullying and Discrimination Prevention and Intervention Training for

Certification Candidates

The amendments to the Dignity Act introduced by Chapter 102 of the Laws of 2012 included a

requirement that school professionals applying for a certificate or license on or after July 1, 2013

complete training on the social patterns of harassment, bullying and discrimination (this timeframe

was extended until December 31, 2013 pursuant to Chapter 90 of the Laws of 2013 [Education

Law §14(5)]). In response to the amendments and after consultation with a work group comprised

of educators and advocates, the Board of Regents approved the following regulatory changes:

➢ Part 52 of the Commissioner’s Regulations has been amended to require teacher

and school leadership preparation programs to include at least six hours of

training in Harassment, Bullying and Discrimination Prevention and Intervention.

➢ A new Subpart 57-4 of the Commissioner’s Regulations has been added to

establish standards under which the Department will approve providers of this

training.

29

➢ • Part 80 of the Commissioner’s Regulations has been amended to require that

anyone applying for an administrative or supervisory service, classroom teaching

service or school service certificate or license on or after December 31, 2013,

shall have completed at least six hours of coursework or training in Harassment,

Bullying and Discrimination Prevention and Intervention.

Responsibilities for Educators

The New York State Code of Ethics for Educators

7

sets clear expectations and principles

to guide educational practice and inspire professional excellence. The first principle

exemplifies the heart of the Dignity Act:

• Educators nurture the intellectual, physical, emotional, social, and civic potential of

each student.

• Educators promote growth in all students through the integration of intellectual,

physical, emotional, social and civic learning.

• They respect the inherent dignity and worth of each individual.

• Educators help students to value their own identity, learn more about their cultural

heritage, and practice social and civic responsibilities.

• They help students to reflect on their own learning and connect it to their life

experience. They engage students in activities that encourage diverse

approaches and solutions to issues, while providing a range of ways for students to

demonstrate their abilities and learning. They foster the development of

students who can analyze, synthesize, evaluate and communicate information

effectively.

The Code of Ethics for Educators, as well as the six Educational Leadership Policy

Standards established by the Council of Chief State School Officers

8

, reinforces the

critical importance of strong leadership within local education agencies.

Educational Leadership Policy Standards

1. Setting a widely shared vision for learning;

2. Developing a school culture and instructional program conducive to student learning

and staff professional growth;

3. Ensuring effective management of the organization, operation, and resources for a

safe, efficient, and effective learning environment;

7

http://www.highered.nysed.gov/tcert/resteachers/codeofethics.html#statement

8

http://www.ccsso.org/Documents/2008/Educational_Leadership_Policy_Standar

ds_2008.pdf

30

4. Collaborating with faculty and community members, responding to diverse

community interests and needs, and mobilizing community resources;

5. Acting with integrity, fairness, and in an ethical manner; and

6. Understanding, responding to, and influencing the political, social, legal, and cultural

contexts.

As leaders in a school district, the superintendent and principals set the overall tone of

respect and responsibility for the entire school community, including faculty, staff,

students, and persons in parental relation. The leadership required of superintendents

and principals is fundamental to the effective implementation of the Dignity Act.

The educational leadership, integrity, and professionalism demonstrated by the

superintendent, principal, faculty and staff are essential to the overall school climate. The

Dignity Act imposes several requirements that involve school leadership and staff.

Specifically, Education Law §13(1) requires that boards create policies, procedures and

guidelines that include provisions which:

• Identify the principal, superintendent or the principal’s or superintendent’s designee as

the school employee charged with receiving reports of harassment, bullying, and

discrimination (Education Law §13[1][a]).

• Enable students and parents to make an oral or written report of harassment, bullying,

and discrimination to teachers, administrators, and other school personnel that the

school district deems appropriate (Education Law §13[1][b]).

• Require school employees who witness harassment, bullying, or discrimination, or

receive an oral or written report of harassment, bullying, or discrimination, to promptly

orally notify the principal, superintendent or their designee not later than one school

day after such school employee witnesses or receives a report of harassment,

bullying, or discrimination, and to file a written report with the principal, superintendent

or their designee not later than two school days after making such oral report

(Education Law §13[1][c]).

• Require the principal, superintendent or their designee to lead or supervise the

thorough investigation of all reports of harassment, bullying, or discrimination, and to

ensure that such investigations are completed promptly after receipt of any written

reports (Education Law §13[1][d]). When an investigation reveals any such verified

harassment, bullying, or discrimination, take prompt actions reasonably calculated to

end the harassment, bullying, or discrimination, eliminate any hostile environment,

create a more positive school culture and climate, prevent recurrence of the behavior

and ensure the safety of the student or students against whom such harassment,

bullying, or discrimination was directed (Education Law §13[1][d][e]).

31

• Require the principal to make a regular annual report on data and trends related to

harassment, bullying, and discrimination to the superintendent (Education Law

§13[1][h]).

• Require the principal, superintendent or their designee to notify promptly the

appropriate local law enforcement agency when such individual believes that

harassment, bullying, or discrimination constitutes criminal conduct (Education Law

§13[1][i]).

Investigation and Follow-up

The Dignity Act requires that the principal, superintendent or the principal’s or

superintendent’s designee lead or supervise the thorough investigation of all

reports of harassment, bullying, and discrimination, and ensure that such

investigation is completed promptly after receipt of any written reports of harassment,

bullying, and discrimination (Education Law §13[1][d]).

The following guidance, Creating a Safe and Respectful Environment in Our Nation’s

Classrooms: Understanding and Intervening in Bullying Behavior was developed by the

U.S. Department of Education National Center on Safe Supportive Learning

Environments (NCSSLE)

8

with input from Barbara-Jane Paris (www.bjparis.org). The

following module entitled Responding to and Reporting Bullying Behavior provides

suggestions which may assist school administrators in fulfilling this vital role.

“It is important to respond to reports of bullying whether you witness the behavior or a

student reporting it to you. It is also important to respond appropriately to a situation. In

some cases, it is possible that what occurred is not bullying, but in order to respond

appropriately you need to carefully research and document allegations. To help ensure

a safe orderly environment while responding to and then following up on incidents, your

school’s policies and procedures should always guide you. Whether a bullying incident

is witnessed or reported by a student, you can follow these simple guidelines called The

Five R’s…

Respond:

When bullying is reported to you or witnessed by you, you must respond and intervene

immediately, making

sure that everyone is safe. Model respectful behavior when you intervene

and reassure the student who has been bullied that what has happened is not his or her fault.

Ask the student, “What do you need from me?” This may help you determine some of your next

steps, including what kind of follow-up is needed.

Research:

It is important to document what the allegations are and to try to capture information from as

many sources as possible, including bystanders, about what happened. Using their exact

8

http://safesupportiveschools.ed.gov/index.php?id=1480

32

language, write down exactly what students say happened. It may also be helpful to try to find

out whether anything happened that might

have

led to the incident. An important part of your

research is to determine whether the incident was indeed

bullying

or another kind of negative or

aggressive interaction.

Record:

Good documentation will provide what is needed to write a thorough, accurate, and helpful

report. Collect and save everything in a folder. In some cases, like cyberbullying, there may be

things like text messages, pictures, or e-mails that should be copies and saved for attachment

to the report.

Report:

Just like responding to the incident itself, writing and filing a formal report of a bullying

incident should always be guided by your school’s policies, Student Code of Conduct and the

commissioner’s regulations. Your

school will probably have its own forms for writing and filing

a report. After thorough research and while reviewing your school’s Student Code of Conduct,

this report is where you would make a determination as to

whether an incident is bullying or

some other form of behavior.

Revisit:

After a plan has been developed for both the student who was bullied, and the student

engaged in bullying behavior, it will be important for you to follow-up with each student to check

and see how things are going. You want to find out if anything has changed, if the plans put into

place are working (or not), and if anything, else needs to be done. Follow-up gives you a

chance to gather more information, and it lets all the students involved know that there is

continued adult support for them.

(NOTE: Refer to Education Law §13[1] and the relevant provisions of Commissioner’s

regulations for specific responsibilities required by New York State Law.)

Maintaining a Circle of Confidentiality

To effectively investigate an alleged incident of harassment or bullying, it is important to

establish processes and procedures that prevent the “re-victimization” of the student.

Some types of harassment may become even more harmful through the perpetration in

gossip and rumors, or through the association of an individual with a marked term or

status in the school community. It is therefore essential to objectively and systematically

collect the facts, but to do so in a manner that does not perpetuate the harm already

caused to the student.

There are several steps that can be taken to limit re-victimization. For example, framing

open-ended questions such as “Have you heard Robert calling any of the girls’ names?”

and following up with “Did you hear him call Susan any names?” is preferable to posing

a pointed question like “Did you hear Robert call Susan an X?” The pointed question,

by its phrasing, inadvertently expands the audience for the harassment.

33

Asking staff not to discuss incidents with one another outside the context of the actual

investigation can also help to limit the re-victimization of a student. Emphasizing an

atmosphere of confidentiality throughout the investigative process also helps prevent

further dissemination of information about the harassment.

Interviewees should be told during the interview that the information they provide will be

kept confidential to the extent permitted under the law, but that there may be instances